Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Vaginectomy

View on Wikipedia| Vaginectomy | |

|---|---|

| ICD-9-CM | 70.4 |

Vaginectomy is a surgery to remove all or part of the vagina. It is one form of treatment for individuals with vaginal cancer or rectal cancer that is used to remove tissue with cancerous cells.[1] It can also be used in gender-affirming surgery. Some people born with a vagina who identify as trans men or as nonbinary may choose vaginectomy in conjunction with other surgeries to make the clitoris more penis-like (metoidioplasty), construct of a full-size penis (phalloplasty), or create a relatively smooth, featureless genital area (genital nullification).[2][3][4][5][6]

If the uterus and ovaries are to remain intact, vaginectomy will leave a canal and opening suitable for draining menstrual discharge. Otherwise, as in genital nullification, a hysterectomy must be performed to avoid the danger of retaining menstrual discharge within the body.[7] In the latter case, thorough removal of vaginal lining is necessary to avoid continued secretion within the body.[8]

In addition to vaginectomy in humans, there have been instances of vaginectomy in other animals to treat vaginal cancer.[9]

Uses

[edit]Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia

[edit]Total or partial vaginectomy along with other procedures like laser vaporization can be used in the treatment of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. These procedures remove the cancerous tissue and provide tissue samples to help identify underlying/invasive cancer while maintaining structure and function of the vagina. This surgery along with radiation therapy used to be the optimal treatment for high-grade vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. However, high rates of recurrence and severe side effects such as vaginal shortening, bleeding and sepsis have narrowed its uses. A partial upper vaginectomy is still the treatment of choice for certain cases of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia as it has success rates ranging from 69 to 88%.[10]

Rectal cancer

[edit]A vaginectomy is often necessary to remove all cancerous tissue associated with rectal cancer. Depending on the extent of rectal cancer, a total or partial vaginectomy may be indicated to improve long-term survival. Following the surgery and removal of rectal tumors, vaginal and rectal reconstructive surgery can improve healing and may help with self-image and sexual function.[11]

Genital gender-affirming surgery

[edit]Although there has not been a consensus on the standard treatment for penis construction in transgender men, a vaginectomy is a vital step in many of the various techniques. Depending on the reconstructive surgeon and which method is used, the basic outline of the procedure involves taking skin from an area of the body like the forearm or abdomen followed by glans sculpture, vaginectomy, urethral anastomosis, scrotoplasty and finished with a penile prosthesis implantation. The ideal outcome of this procedure, as described by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), is to provide an aesthetically appealing penis that enables sexual intercourse and sensitivity. Complications do arise from this procedure which may include tissue death, urethral complications, and infection.[12]

Radial Forearm Free Flap (RAFFF) is one of the techniques considered for total phallic construction.[12] Developed and performed in 1984, RAFFF consists of three stages and a complete vaginectomy is the second stage of RAFFF. The preferred technique is ablation vaginectomy with simultaneous scrotoplasty, which will close the labia majora along the midline.[13]

Recurrent gynecologic malignancies

[edit]An anterior pelvic exenteration with total vaginectomy (AETV) is a procedure that removes the urinary system (kidneys, ureters, bladder, urethra) as well as the gynecologic system (ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, vagina) and is used as treatment of recurrent gynecologic cancers. A total pelvic exenteration can also be used as treatment which involves the removal of the rectum in addition to the urinary and gynecologic systems. The decision between the two procedures depends on extent of the cancer. Potential benefits of an AETV over a total pelvic exenteration include reduced risk of intestinal injury.[14]

Reversal of vaginoplasty

[edit]Neovaginectomy has been performed to remove the neovagina following vaginoplasty, for instance in transgender women who experience neovaginal complications or those who choose to detransition.[15]

Contraindications

[edit]The safety of vaginectomy can depend on individual medical conditions and the subsequent risks they pose. For example, for people with diabetes mellitus, potential contraindications for vaginectomy include wound-healing difficulty; for people who prefer to not undergo hormone therapy, potential contraindications include gonad removal (oophorectomy or orchiectomy).[16]

Risks/complications

[edit]Many people who undergo vaginectomy do so for sexual health and intimacy. However, risks of vaginectomy include post-operative sensory issues that range from lack of sensation to excessive sensation, such as hypersensitivity or even pain.[16] To address this, skin grafting is often done with vaginectomy to allow recovery of sexual function.[17]

Other risks may involve consequences of the procedure itself. For example, possible injuries include rectal injury (due to the proximity of the structures), development of a fistula (an abnormal connection between two body parts), or, for people who have phalloplasty done in conjunction with vaginectomy, irritation or even erosion of the skin of the phallus. Some of these locations may be suture sites; irritation of these sites may increase likelihood of infection.[18]

There are pre- and post-operative steps that can be taken to minimize complications from vaginectomy. For example, other procedures that are often performed in conjunction with vaginectomy, such as metoidioplasty and phallourethroplasty, can be performed in two stages to increase the likelihood of a favorable cosmetic outcome.[19] Also, waiting for a period of time after completing a procedure, usually a minimum of 4 months, ensures that the person undergoing the surgery is clear of infections or risk thereof. Thus, procedures towards the end of the gender-affirming process, such as penile prosthesis placement, are usually done separately.[19]

For people with vaginal cancer, vaginectomy can be done partially, instead of radically, depending on the individual person's need as determined by the tumor's size, location, and stage. For example, some people had simple hysterectomy (a procedure that removes a uterus) and then discovered cervical cancer. At this point, upper vaginectomy - along with other suggested procedures such as lymphadenectomy (a procedure that removes lymph nodes) - may be suggested to people who would prefer to keep ovarian function intact.[20] This is an option depending on the invasiveness and severity of the disease and is specifically for individuals with stage I cancer in the upper vagina.[21]

Techniques

[edit]Vaginectomy procedures are described by the amount of vaginal tissue removed from an individual which is dependent on the reason for surgery.

Removal of cancerous tissue

[edit]For vaginectomy as a treatment to cancer, tissue is removed in response to the extent of the cancer.[7] A partial vaginectomy removes only the outer most layers of tissue and is performed if the abnormal cells are only found at the skin level. For example, individuals with rectal cancer that has spread to vaginal tissue may undergo a partial vaginectomy in which the posterior wall of the vagina near the anus is removed. A surgeon will make an incision on the abdomen in order to reach the vagina for removal. The operation to remove vaginal tissue will typically happen with at the same time as a colostomy and a abdominoperineal resection in which a portion of the colon is rediverted into a colostomy bag and the rectum is removed. A partial vaginectomy leaves much of the muscles in the vagina intact and can be followed by a vaginal reconstruction surgery.[22]

If more invasive cancer is found, a more complete vaginectomy is performed to remove all cancerous tumors and cells.[23]

Gender-affirming surgery

[edit]In vaginectomy for gender-affirming surgeries, the tissue from the vaginal wall is removed while outer labial flaps are sometimes left in place for other reconstructive surgeries.[24] The procedure gives people who were assigned female sex at birth but do not identify as female, such as transgender men and transmasculine or otherwise nonbinary individuals, genitalia that aids in reducing gender dysphoria and affirming their gender identity through their physical appearance.[3][19] Counseling is often provided to people considering gender-affirming surgeries prior to procedures in order to limit regret later down the line.[25] In the context of gender-affirming surgery, procedures are categorized as either colpocleisis or total vaginectomy.[26]

Colpocleisis only removes a layer of epithelium or the outer most tissue in the vaginal canal. The walls of the vaginal canal are then sutured shut, but a small channel and the perineum area between the vagina and anus is typically left open to allow for discharge to be emitted from the body. A colpoclesis procedure is sometimes preceded by an oophorectomy and or a hysterectomy to remove the ovaries and uterus which reduces risks of complications from leaving these structures intact and reduces the amount of vaginal discharge. If the ovaries and uterus are left intact there are greater levels of vaginal discharge remain that can contribute to further gender dysphoria in individuals.[26]

Total vaginectomy is becoming the more common form of vaginectomy in gender-affirming surgeries. It involves removal of the full thickness of vaginal wall tissue and can be approached vaginally, as in a transvaginal or transperineal vaginectomy, or abdominally through the area near the stomach, as in an abdominal vaginectomy. In addition to a greater degree of tissue removal, total vaginectomy also involves a more complete closure of the space in the vaginal canal. In comparison to colpocleisis, it is more often preceded by separate oophorectomy and hysterectomy procedures and proceeded by a separate gender reconstruction surgery such as to create a neophallus.[6] Total vaginectomy surgery is sometimes performed using robotic assistance which allows for increased speed and precision for a procedure with less blood loss and a quicker recovery time.[26]

Recovery

[edit]Individuals should expect to experience some pain in the first week after the operation. The average hospital stay after operation was a week and all individuals are discharged with a catheter, which is removed after 2–3 weeks.[8] At discharge, individuals learn how to take care of the incisions and must limit their physical activity for the initial 2–3 weeks. Swelling of the abdominal area or abdominal pain are signs of complications during recovery. Some common complications that occur are urethral fistulas and strictures in individuals who undergo vaginectomy and phallic reconstruction for gender-affirming surgeries. This is due to poor blood supply and improper width of the new urethra.[27]

History

[edit]Vaginal surgeries have been around throughout medical history. Even before the invention of modern surgical techniques such as anesthesia and sterile tools, there have been many reports of vaginal surgery to treat problems such as prolapse, vaginal fistula, and poor bladder control. For example, the first documented vaginal hysterectomy was performed in 1521 during the Italian Renaissance.[28] Surgical techniques and medical knowledge developed slowly over time until the invention of anesthesia and antisepsis allowed for the age of modern surgery in the mid-nineteenth century. Since then, many techniques and instruments were developed specifically for vaginal surgery like the standardization of sutures in 1937 which greatly improved survival rates by lowering risk of infection.[29] Noble Sproat Heaney developed the "Heaney Stitch" in 1940 to standardize the technique for vaginal hysterectomy. The first documented case of radical vaginal surgery was in February 2003 where a person underwent a radical hysterectomy with vaginectomy and reconstruction.[30]

Other animals

[edit]Vaginectomies are also performed outside of the human species. Similarly to humans, animals may also undergo vaginectomies to treat cancer of the vagina. Domesticated animals and pets such as dogs, cats, and horses are more likely to receive a vaginectomy because of its complicated procedure.[9]

Dogs

[edit]Total and partial vaginectomies are not commonly done on dogs as they are complex and are not considered first line therapy however, if other procedures do not work a vaginectomy can be performed on a dog. The most common reasons for a dog to get a vaginectomy include cancer and chronic infection of the vagina. Tumors on the vagina and vulva of the dog accounts for 2.5%-3% of cancers affecting dogs and vaginectomies are one of the treatments to remove and cure the dog.[31] Possible complications from the surgery include loss of bladder control, swelling, and improper skin healing.[9] However, loss of bladder control was fixed spontaneously within 60 days of the operation and the dogs survived at least 100 days with no disease.[31]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kulkarni A, Dogra N, Zigras T (April 2022). "Innovations in the Management of Vaginal Cancer". Current Oncology. 29 (5): 3082–3092. doi:10.3390/curroncol29050250. PMC 9139564. PMID 35621640.

- ^ "Non-Binary Options For Metoidioplasty". Metoidioplasty.net. 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ a b Frey JD, Poudrier G, Chiodo MV, Hazen A (March 2017). "An Update on Genital Reconstruction Options for the Female-to-Male Transgender Patient: A Review of the Literature". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 139 (3): 728–737. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000003062. PMID 28234856.

- ^ Walton AB, Hellstrom WJ, Garcia MM (October 2021). "Options for Masculinizing Genital Gender Affirming Surgery: A Critical Review of the Literature and Perspectives for Future Directions". Sexual Medicine Reviews. 9 (4): 605–618. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2021.07.002. PMID 34493480. S2CID 237440377.

- ^ Bizic M, Stojanovic B, Bencic M, Bordás N, Djordjevic M (November 2020). "Overview on metoidioplasty: variants of the technique". International Journal of Impotence Research. 33 (7): 762–770. doi:10.1038/s41443-020-00346-y. PMID 32826970. S2CID 221217936.

- ^ a b Heston AL, Esmonde NO, Dugi DD, Berli JU (June 2019). "Phalloplasty: techniques and outcomes". Translational Andrology and Urology. 8 (3): 254–265. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.05.05. PMC 6626313. PMID 31380232.

- ^ a b "Surgical Treatment of Vaginal Cancer". EMedicine Obstetrics and Gynecology. 26 August 2021.

- ^ a b Medina CA, Fein LA, Salgado CJ (October 2018). "Total vaginectomy and urethral lengthening at time of neourethral prelamination in transgender men". International Urogynecology Journal. 29 (10): 1463–1468. doi:10.1007/s00192-017-3517-y. PMID 29188324. S2CID 21484067.

- ^ a b c Zambelli D, Valentini S, Ballotta G, Cunto M (January 2022). "Partial Vaginectomy, Complete Vaginectomy, Partial Vestibule-Vaginectomy, Vulvo-Vestibule-Vaginectomy and Vulvo-Vestibulectomy: Different Surgical Procedure in Order to Better Approach Vaginal Diseases". Animals. 12 (2): 196. doi:10.3390/ani12020196. PMC 8773321. PMID 35049818.

- ^ Frega A, Sopracordevole F, Assorgi C, Lombardi D, DE Sanctis V, Catalano A, et al. (January 2013). "Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia: a therapeutical dilemma". Anticancer Research. 33 (1): 29–38. PMID 23267125.

- ^ McArdle A, Bischof DA, Davidge K, Swallow CJ, Winter DC (November 2012). "Vaginal reconstruction following radical surgery for colorectal malignancies: a systematic review of the literature". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 19 (12): 3933–3942. doi:10.1245/s10434-012-2503-3. PMID 23010729. S2CID 25690425.

- ^ a b Falcone M, Preto M, Blecher G, Timpano M, Gontero P (June 2021). "Total phallic construction techniques in transgender men: an updated narrative review". Translational Andrology and Urology. 10 (6): 2583–2595. doi:10.21037/tau-20-1340. PMC 8261414. PMID 34295745.

- ^ Yao A, Ingargiola MJ, Lopez CD, Sanati-Mehrizy P, Burish NM, Jablonka EM, Taub PJ (June 2018). "Total penile reconstruction: A systematic review". Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 71 (6): 788–806. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2018.02.002. PMID 29622476. S2CID 4591969.

- ^ Kaur M, Joniau S, D'Hoore A, Vergote I (September 2014). "Indications, techniques and outcomes for pelvic exenteration in gynecological malignancy". Current Opinion in Oncology. 26 (5): 514–520. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000109. PMID 25050632. S2CID 205546063.

- ^ Adelowo, Amos; Weber-LeBrun, Emily E.; Young, Stephen B. (May 2009). "Neovaginectomy Following Vaginoplasty in a Male-to-Female Transgender Patient". Journal of Pelvic Medicine and Surgery. 15 (3): 101–104. doi:10.1097/SPV.0b013e3181aacc41. ISSN 1542-5983.

- ^ a b Blasdel G, Zhao LC, Bluebond-Langner R (2022). Keuroghlian AS, Potter J, Reisner SL (eds.). Surgical Gender Affirmation. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. Retrieved 2022-07-26.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Brackmann M, Reynolds RK (2020). "Gynecology". In Doherty GM (ed.). Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery (15 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill LLC. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ Gaddis ML, Grimstad FW (2020). "The Transgender Patient". In Tintinalli JE, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, Meckler GD (eds.). Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (9th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ a b c Garcia MM (2020). McAninch JW, Lue TF (eds.). Genital Gender-Affirming Surgery: Patient Care, Decision Making, and Surgery Options (19th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill. Retrieved 2022-07-26.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Garcia LM, Holschneider CH (2019). "Premalignant & Malignant Disorders of the Uterine Cervix". In DeCherney AH, Nathan L, Laufer N, Roman AS (eds.). CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Obstetrics & Gynecology (12th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ Karam A (2019). "Premalignant & Malignant Disorders of the Vulva & Vagina". In DeCherney AH, Nathan L, Laufer N, Roman AS (eds.). CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Obstetrics & Gynecology (12th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ Maingot R, Zinner M, Ashley SW, Hines OH (2019). Maingot's abdominal operations (Thirteenth ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-07-184429-1. OCLC 1225946158.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hatch KD (2019). Operative techniques in gynecologic surgery Gynecologic oncology. Philadelphia. ISBN 978-1-4963-6074-8. OCLC 1079400829.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Zeplin PH (2020). Reconstructive and aesthetic genital surgery. Stuttgart. ISBN 978-3-13-241306-1. OCLC 1080250689.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bustos VP, Bustos SS, Mascaro A, Del Corral G, Forte AJ, Ciudad P, et al. (March 2021). "Regret after Gender-affirmation Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prevalence". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Global Open. 9 (3) e3477. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000003477. PMC 8099405. PMID 33968550.

- ^ a b c Coulter M, Diamond DA, Estrada C, Grimstad F, Yu R, Doyle P (June 2022). "Vaginectomy in Transmasculine Patients: A Review of Techniques in an Emerging Field". Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery. 28 (6): e222 – e230. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000001132. PMID 35234183. S2CID 247190683.

- ^ Rohrmann D, Jakse G (November 2003). "Urethroplasty in female-to-male transsexuals". European Urology. 44 (5): 611–614. doi:10.1016/S0302-2838(03)00356-7. PMID 14572764.

- ^ Tizzano AP (2007). "Historical Milestones in Female Pelvic Surgery, Gynecology, and Female Urology". Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. Elsevier. pp. 3–14. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-02902-5.50007-1. ISBN 978-0-323-02902-5.

- ^ Muffly TM, Tizzano AP, Walters MD (March 2011). "The history and evolution of sutures in pelvic surgery". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 104 (3): 107–112. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2010.100243. PMC 3046193. PMID 21357979.

- ^ Ling B, Gao Z, Sun M, Sun F, Zhang A, Zhao W, Hu W (April 2008). "Laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with vaginectomy and reconstruction of vagina in patients with stage I of primary vaginal carcinoma". Gynecologic Oncology. 109 (1): 92–96. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.12.012. PMID 18237770.

- ^ a b Ogden JA, Selmic LE, Liptak JM, Oblak ML, Culp WT, de Mello Souza CH, et al. (August 2020). "Outcomes associated with vaginectomy and vulvovaginectomy in 21 dogs". Veterinary Surgery. 49 (6): 1132–1143. doi:10.1111/vsu.13466. PMID 32515509. S2CID 219549190.

External links

[edit]- The vaginectomy article on the Mad Gender Science wiki Archived 2020-09-19 at the Wayback Machine

Vaginectomy

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Procedure Overview

Surgical Definition and Types

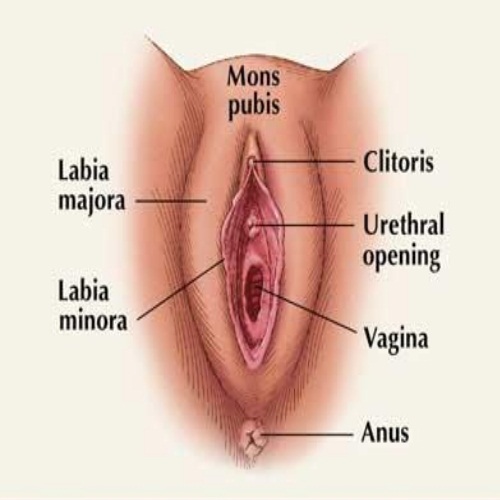

Vaginectomy is a surgical procedure involving the excision of part or all of the vaginal canal, the muscular tube connecting the uterus to the vulva in biological females.[8] This operation is typically performed under general anesthesia and may involve open, laparoscopic, or robotic-assisted approaches, depending on the extent and indication.[9] The procedure aims to resect diseased tissue while preserving as much function as possible, though it often necessitates reconstruction or diversion of urinary and fecal pathways in extensive cases.[2] Vaginectomies are classified primarily by the anatomical extent of resection. A partial vaginectomy removes only a segment of the vaginal wall, such as the upper (proximal) portion near the vaginal vault or the lower (distal) portion adjacent to the introitus, preserving the remainder of the canal.[10] This type is indicated for localized lesions, minimizing disruption to sexual and urinary function.[11] In contrast, a total vaginectomy entails complete removal of the vaginal canal from the introitus to the vaginal apex, often requiring neovaginal reconstruction using grafts or flaps to restore pelvic floor integrity.[12] Radical vaginectomy extends beyond the vagina to include adjacent structures like parametrial tissues, paravaginal tissues, and sometimes pelvic lymph nodes, typically for invasive malignancies with risk of local spread.[12] [11] Additional subclassifications may arise based on concomitant procedures or anatomical focus, such as vestibule-vaginectomy (incorporating removal of the vaginal vestibule) or vulvo-vaginectomy (extending to vulvar tissues), though these are less standardized and often tailored to specific pathologies.[1] Operative morbidity varies by type, with radical procedures carrying higher risks of hemorrhage, infection, and fistula formation due to broader dissection.[9]Anatomical Considerations

The vagina constitutes a fibromuscular canal extending posterosuperiorly from the external vaginal orifice in the perineum to the cervix of the uterus, measuring approximately 7.5 cm along the anterior wall and 9 cm along the posterior wall.[13] It lies anterior to the rectum and posterior to the bladder and urethra, with lateral relations to the ureters and levator ani muscles.[14] These spatial relationships necessitate precise dissection during vaginectomy to avoid inadvertent injury to adjacent organs, particularly the rectum posteriorly and bladder anteriorly, which share thin fascial separations.[14] Structurally, the vagina features rugose walls formed by an inner mucosal layer of non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, a middle muscular layer with circular and longitudinal smooth muscle fibers, and an outer adventitia blending with surrounding pelvic fascia.[13] The upper vagina, including the vaginal vault, integrates with the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments for support, forming a cardinal-uterosacral complex approximately 2-3 cm in length that stabilizes the fornices.[15] In total vaginectomy, removal extends to this vault level, requiring mobilization while preserving or ligating ligamentous attachments to maintain pelvic floor integrity.[15] Arterial supply derives primarily from the vaginal artery (a branch of the internal iliac artery) and contributions from the uterine artery proximally, with anastomoses to the internal pudendal artery distally, forming a rich submucosal plexus.[14][13] Venous drainage parallels via a vaginal plexus into the internal iliac veins.[14] Surgical excision demands meticulous hemostasis due to this vascular density, particularly during circumferential mobilization of the vaginal walls.[14] Innervation involves autonomic fibers from the uterovaginal plexus—sympathetic via the hypogastric plexus and parasympathetic via pelvic splanchnic nerves (S2-S4)—predominating in the proximal four-fifths, while the distal fifth receives somatic sensory input from the pudendal nerve.[14][13] This distribution implies potential sensory preservation in partial procedures but complete denervation in total vaginectomy, influencing postoperative sensation and function.[13] Lymphatic drainage varies by segment: the superior vagina drains to external and internal iliac nodes, the middle to internal iliac nodes, and the inferior to superficial inguinal nodes.[14][13] In oncologic vaginectomy, this segmental pattern guides lymph node dissection to ensure adequate clearance, particularly for upper vaginal lesions involving iliac chains.[14]Indications

Oncological Indications

Vaginectomy is primarily indicated for the surgical management of vaginal cancer, a rare malignancy accounting for approximately 0.6% of gynecologic cancers, where resection offers curative potential in early stages not amenable to radiation or chemotherapy alone.[9][2] For stage I and II squamous cell carcinoma or melanoma of the vagina, partial or total vaginectomy allows removal of the tumor with adequate margins while preserving surrounding structures when feasible.[10] In cases of superficial invasion less than 0.5 cm into the vaginal wall, a simple partial vaginectomy suffices, minimizing morbidity compared to more radical approaches.[16] For vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN), a pre-invasive lesion often linked to human papillomavirus, proximal partial vaginectomy serves as an effective therapeutic option, particularly for upper vaginal involvement post-hysterectomy, with studies reporting low recurrence rates and enabling histopathological confirmation to rule out occult invasion.[3] This procedure identifies invasive cancer in up to 12% of VaIN cases, underscoring its diagnostic value alongside treatment.[17] In recurrent or persistent high-grade VaIN refractory to topical therapies like 5-fluorouracil, upper vaginectomy provides durable control, though long-term surveillance with cytology and colposcopy remains essential due to multifocal disease risk.[18] Beyond primary vaginal neoplasms, vaginectomy features in en bloc resections for adjacent gynecologic cancers with vaginal extension, such as early-stage (FIGO I-II) disease following radical hysterectomy or for vaginal recurrences of cervical or endometrial carcinoma in post-hysterectomy patients.[19][18] For advanced or recurrent pelvic cancers involving the vagina, it may form part of pelvic exenteration, though this radical procedure is reserved for select cases due to high morbidity, with 5-year survival rates varying from 20-60% depending on margins and nodal status.[20] In non-gynecologic contexts, such as rectal cancer with vaginal invasion, partial or total vaginectomy ensures oncologic clearance, often combined with colorectal resection.[9] Surgical candidacy prioritizes tumor localization via imaging and biopsy, with neoadjuvant therapy considered for borderline resectable lesions to optimize outcomes.[21]Non-Oncological Medical Indications

Vaginectomy serves as a component of obliterative procedures for severe pelvic organ prolapse (POP) in women who do not anticipate future vaginal intercourse and for whom reconstructive options may be unsuitable due to comorbidities or frailty. In these cases, partial or total vaginectomy facilitates vaginal closure or narrowing, often alongside colpocleisis or pelvic herniorrhaphy, to restore anatomic support and alleviate symptoms such as pelvic pressure, urinary incontinence, or bowel dysfunction.[22][23] This approach prioritizes durability over vaginal patency, with anatomic success rates exceeding 90% in select cohorts.[24] Such indications are typically reserved for postmenopausal or elderly patients with advanced prolapse (e.g., stage III-IV), where less invasive therapies like pessaries have failed and reconstructive surgery risks (e.g., mesh erosion or recurrence) outweigh benefits. Vaginectomy with herniorrhaphy in high-risk populations demonstrates low perioperative morbidity, including complication rates under 10% for infection or bleeding, and short hospital stays averaging 2-3 days.[25][23] Long-term follow-up indicates sustained prolapse correction without significant impact on urinary or defecatory function in most cases.[22] Other benign gynecologic conditions, such as refractory fistulas or extensive benign lesions (e.g., large Bartholin gland cysts unresponsive to drainage), may rarely warrant partial vaginectomy to excise diseased tissue and prevent recurrence, though evidence is limited to case reports and not standardized.[26] These applications emphasize preservation of continence and sexual alternatives when feasible, with preoperative counseling on irreversible loss of vaginal capacity.Elective Indications in Gender Dysphoria

Vaginectomy serves as an elective intervention for individuals with gender dysphoria assigned female at birth who identify as male, aiming to resolve distress stemming from the presence of vaginal anatomy. This procedure addresses dysphoria by excising vaginal mucosa and closing the canal, often integrated with phalloplasty or metoidioplasty to enable neophallic reconstruction and reduce issues like vaginal discharge.[5][27] It is pursued after initial treatments such as testosterone therapy fail to fully mitigate genital-related incongruence, with empirical data indicating improved psychological well-being post-surgery in qualifying cases.[28] Eligibility criteria, aligned with guidelines from bodies like the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), emphasize persistent gender dysphoria documented over at least six months by mental health professionals experienced in the condition.[29] Candidates must exhibit capacity for fully informed consent, understanding irreversible effects including infertility, and typically undergo at least 12 months of hormone therapy to evaluate its influence on dysphoria unless medically contraindicated.[30] Age of majority (18 years) is required, alongside one referral letter from a qualified mental health provider confirming readiness.[31] Not all individuals with gender dysphoria seek vaginectomy; it is indicated selectively when genital incongruence persists despite conservative measures, with studies reporting procedure rates among transgender males ranging from 20-50% in surgical cohorts.[32] Long-term follow-up data support its role in dysphoria alleviation, with regret rates below 1% in gender-affirming genital surgeries, though methodological limitations in older studies and potential underreporting warrant caution in interpreting universal efficacy.[33][34] Comorbid pelvic floor dysfunction may influence candidacy, as preoperative assessment identifies risks exacerbating postoperative symptoms.[35]Contraindications and Preoperative Assessment

Absolute and Relative Contraindications

Absolute contraindications to vaginectomy include active pelvic sepsis or untreated local infection, which pose an unacceptably high risk of disseminating infection intraoperatively, and uncorrectable coagulopathy or severe decompensated cardiopulmonary disease precluding safe general anesthesia.[36] In oncologic settings involving radical procedures such as pelvic exenteration, distant metastases, peritoneal carcinomatosis, or unresectable involvement of structures like the pelvic sidewall or sciatic foramen represent absolute contraindications, as they preclude curative intent or render surgery futile.[37] Relative contraindications encompass conditions that elevate complication risks but may be mitigated with optimization, such as prior pelvic radiation inducing fibrosis and adhesions, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus impairing wound healing, morbid obesity complicating access and increasing infection rates, and active smoking exacerbating vascular compromise.[36][38] In elective contexts like gender-affirming surgery for individuals with gender dysphoria, relative contraindications include unresolved severe psychiatric comorbidities or lack of preoperative mental health clearance, which protocols require to ensure informed consent and postoperative adherence.[39][40]| Type | Examples | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute | Active pelvic infection; uncorrectable coagulopathy; distant metastases in oncology | Immediate life-threatening risks or inability to achieve therapeutic goal[37][36] |

| Relative | Prior radiation; diabetes; obesity; untreated psychiatric instability (elective cases) | Increased perioperative morbidity manageable with preoperative intervention[39][38] |