Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hadamard code

View on WikipediaThis article's lead section may be too long. (May 2020) |

| Hadamard code | |

|---|---|

| Named after | Jacques Hadamard |

| Classification | |

| Type | Linear block code |

| Block length | |

| Message length | |

| Rate | |

| Distance | |

| Alphabet size | |

| Notation | -code |

| Augmented Hadamard code | |

|---|---|

| Named after | Jacques Hadamard |

| Classification | |

| Type | Linear block code |

| Block length | |

| Message length | |

| Rate | |

| Distance | |

| Alphabet size | |

| Notation | -code |

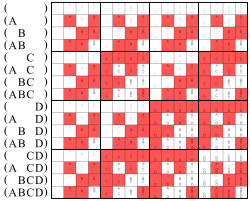

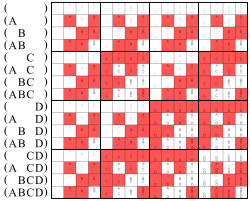

Here the white fields stand for 0

and the red fields for 1

The Hadamard code is an error-correcting code named after the French mathematician Jacques Hadamard that is used for error detection and correction when transmitting messages over very noisy or unreliable channels. In 1971, the code was used to transmit photos of Mars back to Earth from the NASA space probe Mariner 9.[1] Because of its unique mathematical properties, the Hadamard code is not only used by engineers, but also intensely studied in coding theory, mathematics, and theoretical computer science. The Hadamard code is also known under the names Walsh code, Walsh family,[2] and Walsh–Hadamard code[3] in recognition of the American mathematician Joseph Leonard Walsh.

The Hadamard code is an example of a linear code of length over a binary alphabet. Unfortunately, this term is somewhat ambiguous as some references assume a message length while others assume a message length of . In this article, the first case is called the Hadamard code while the second is called the augmented Hadamard code.

The Hadamard code is unique in that each non-zero codeword has a Hamming weight of exactly , which implies that the distance of the code is also . In standard coding theory notation for block codes, the Hadamard code is a -code, that is, it is a linear code over a binary alphabet, has block length , message length (or dimension) , and minimum distance . The block length is very large compared to the message length, but on the other hand, errors can be corrected even in extremely noisy conditions.

The augmented Hadamard code is a slightly improved version of the Hadamard code; it is a -code and thus has a slightly better rate while maintaining the relative distance of , and is thus preferred in practical applications. In communication theory, this is simply called the Hadamard code and it is the same as the first order Reed–Muller code over the binary alphabet.[4]

Normally, Hadamard codes are based on Sylvester's construction of Hadamard matrices, but the term “Hadamard code” is also used to refer to codes constructed from arbitrary Hadamard matrices, which are not necessarily of Sylvester type. In general, such a code is not linear. Such codes were first constructed by Raj Chandra Bose and Sharadchandra Shankar Shrikhande in 1959.[5] If n is the size of the Hadamard matrix, the code has parameters , meaning it is a not-necessarily-linear binary code with 2n codewords of block length n and minimal distance n/2. The construction and decoding scheme described below apply for general n, but the property of linearity and the identification with Reed–Muller codes require that n be a power of 2 and that the Hadamard matrix be equivalent to the matrix constructed by Sylvester's method.

The Hadamard code is a locally decodable code, which provides a way to recover parts of the original message with high probability, while only looking at a small fraction of the received word. This gives rise to applications in computational complexity theory and particularly in the design of probabilistically checkable proofs. Since the relative distance of the Hadamard code is 1/2, normally one can only hope to recover from at most a 1/4 fraction of error. Using list decoding, however, it is possible to compute a short list of possible candidate messages as long as fewer than of the bits in the received word have been corrupted.

In code-division multiple access (CDMA) communication, the Hadamard code is referred to as Walsh Code, and is used to define individual communication channels. It is usual in the CDMA literature to refer to codewords as “codes”. Each user will use a different codeword, or “code”, to modulate their signal. Because Walsh codewords are mathematically orthogonal, a Walsh-encoded signal appears as random noise to a CDMA capable mobile terminal, unless that terminal uses the same codeword as the one used to encode the incoming signal.[6]

History

[edit]Hadamard code is the name that is most commonly used for this code in the literature. However, in modern use these error correcting codes are referred to as Walsh–Hadamard codes.

There is a reason for this:

Jacques Hadamard did not invent the code himself, but he defined Hadamard matrices around 1893, long before the first error-correcting code, the Hamming code, was developed in the 1940s.

The Hadamard code is based on Hadamard matrices, and while there are many different Hadamard matrices that could be used here, normally only Sylvester's construction of Hadamard matrices is used to obtain the codewords of the Hadamard code.

James Joseph Sylvester developed his construction of Hadamard matrices in 1867, which actually predates Hadamard's work on Hadamard matrices. Hence the name Hadamard code is disputed and sometimes the code is called Walsh code, honoring the American mathematician Joseph Leonard Walsh.

An augmented Hadamard code was used during the 1971 Mariner 9 mission to correct for picture transmission errors. The binary values used during this mission were 6 bits long, which represented 64 grayscale values.

Because of limitations of the quality of the alignment of the transmitter at the time (due to Doppler Tracking Loop issues) the maximum useful data length was about 30 bits. Instead of using a repetition code, a [32, 6, 16] Hadamard code was used.

Errors of up to 7 bits per 32-bit word could be corrected using this scheme. Compared to a 5-repetition code, the error correcting properties of this Hadamard code are much better, yet its rate is comparable. The efficient decoding algorithm was an important factor in the decision to use this code.

The circuitry used was called the "Green Machine". It employed the fast Fourier transform which can increase the decoding speed by a factor of three. Since the 1990s use of this code by space programs has more or less ceased, and the NASA Deep Space Network does not support this error correction scheme for its dishes that are greater than 26 m.

Constructions

[edit]While all Hadamard codes are based on Hadamard matrices, the constructions differ in subtle ways for different scientific fields, authors, and uses. Engineers, who use the codes for data transmission, and coding theorists, who analyse extremal properties of codes, typically want the rate of the code to be as high as possible, even if this means that the construction becomes mathematically slightly less elegant.

On the other hand, for many applications of Hadamard codes in theoretical computer science it is not so important to achieve the optimal rate, and hence simpler constructions of Hadamard codes are preferred since they can be analyzed more elegantly.

Construction using inner products

[edit]When given a binary message of length , the Hadamard code encodes the message into a codeword using an encoding function This function makes use of the inner product of two vectors , which is defined as follows:

Then the Hadamard encoding of is defined as the sequence of all inner products with :

As mentioned above, the augmented Hadamard code is used in practice since the Hadamard code itself is somewhat wasteful. This is because, if the first bit of is zero, , then the inner product contains no information whatsoever about , and hence, it is impossible to fully decode from those positions of the codeword alone. On the other hand, when the codeword is restricted to the positions where , it is still possible to fully decode . Hence it makes sense to restrict the Hadamard code to these positions, which gives rise to the augmented Hadamard encoding of ; that is, .

Construction using a generator matrix

[edit]The Hadamard code is a linear code, and all linear codes can be generated by a generator matrix . This is a matrix such that holds for all , where the message is viewed as a row vector and the vector-matrix product is understood in the vector space over the finite field . In particular, an equivalent way to write the inner product definition for the Hadamard code arises by using the generator matrix whose columns consist of all strings of length , that is,

where is the -th binary vector in lexicographical order. For example, the generator matrix for the Hadamard code of dimension is:

The matrix is a -matrix and gives rise to the linear operator .

The generator matrix of the augmented Hadamard code is obtained by restricting the matrix to the columns whose first entry is one. For example, the generator matrix for the augmented Hadamard code of dimension is:

Then is a linear mapping with .

For general , the generator matrix of the augmented Hadamard code is a parity-check matrix for the extended Hamming code of length and dimension , which makes the augmented Hadamard code the dual code of the extended Hamming code. Hence an alternative way to define the Hadamard code is in terms of its parity-check matrix: the parity-check matrix of the Hadamard code is equal to the generator matrix of the Hamming code.

Construction using general Hadamard matrices

[edit]Hadamard codes are obtained from an n-by-n Hadamard matrix H. In particular, the 2n codewords of the code are the rows of H and the rows of −H. To obtain a code over the alphabet {0,1}, the mapping −1 ↦ 1, 1 ↦ 0, or, equivalently, x ↦ (1 − x)/2, is applied to the matrix elements. That the minimum distance of the code is n/2 follows from the defining property of Hadamard matrices, namely that their rows are mutually orthogonal. This implies that two distinct rows of a Hadamard matrix differ in exactly n/2 positions, and, since negation of a row does not affect orthogonality, that any row of H differs from any row of −H in n/2 positions as well, except when the rows correspond, in which case they differ in n positions.

To get the augmented Hadamard code above with , the chosen Hadamard matrix H has to be of Sylvester type, which gives rise to a message length of .

Distance

[edit]The distance of a code is the minimum Hamming distance between any two distinct codewords, i.e., the minimum number of positions at which two distinct codewords differ. Since the Walsh–Hadamard code is a linear code, the distance is equal to the minimum Hamming weight among all of its non-zero codewords. All non-zero codewords of the Walsh–Hadamard code have a Hamming weight of exactly by the following argument.

Let be a non-zero message. Then the following value is exactly equal to the fraction of positions in the codeword that are equal to one:

The fact that the latter value is exactly is called the random subsum principle. To see that it is true, assume without loss of generality that . Then, when conditioned on the values of , the event is equivalent to for some depending on and . The probability that happens is exactly . Thus, in fact, all non-zero codewords of the Hadamard code have relative Hamming weight , and thus, its relative distance is .

The relative distance of the augmented Hadamard code is as well, but it no longer has the property that every non-zero codeword has weight exactly since the all s vector is a codeword of the augmented Hadamard code. This is because the vector encodes to . Furthermore, whenever is non-zero and not the vector , the random subsum principle applies again, and the relative weight of is exactly .

Local decodability

[edit]A locally decodable code is a code that allows a single bit of the original message to be recovered with high probability by only looking at a small portion of the received word.

A code is -query locally decodable if a message bit, , can be recovered by checking bits of the received word. More formally, a code, , is -locally decodable, if there exists a probabilistic decoder, , such that (Note: represents the Hamming distance between vectors and ):

, implies that

Theorem 1: The Walsh–Hadamard code is -locally decodable for all .

Lemma 1: For all codewords, in a Walsh–Hadamard code, , , where represent the bits in in positions and respectively, and represents the bit at position .

Proof of lemma 1

[edit]Let be the codeword in corresponding to message .

Let be the generator matrix of .

By definition, . From this, . By the construction of , . Therefore, by substitution, .

Proof of theorem 1

[edit]To prove theorem 1 we will construct a decoding algorithm and prove its correctness.

Algorithm

[edit]Input: Received word

For each :

- Pick uniformly at random.

- Pick such that , where is the -th standard basis vector and is the bitwise xor of and .

- .

Output: Message

Proof of correctness

[edit]For any message, , and received word such that differs from on at most fraction of bits, can be decoded with probability at least .

By lemma 1, . Since and are picked uniformly, the probability that is at most . Similarly, the probability that is at most . By the union bound, the probability that either or do not match the corresponding bits in is at most . If both and correspond to , then lemma 1 will apply, and therefore, the proper value of will be computed. Therefore, the probability is decoded properly is at least . Therefore, and for to be positive, .

Therefore, the Walsh–Hadamard code is locally decodable for .

Optimality

[edit]For k ≤ 7 the linear Hadamard codes have been proven optimal in the sense of minimum distance.[7]

See also

[edit]- Zadoff–Chu sequence — improve over the Walsh–Hadamard codes

References

[edit]- ^ Malek, Massoud (2006). "Hadamard Codes". Coding Theory (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-01-09.

- ^ Amadei, M.; Manzoli, Umberto; Merani, Maria Luisa (2002-11-17). "On the assignment of Walsh and quasi-orthogonal codes in a multicarrier DS-CDMA system with multiple classes of users". Global Telecommunications Conference, 2002. GLOBECOM'02. IEEE. Vol. 1. IEEE. pp. 841–845. doi:10.1109/GLOCOM.2002.1188196. ISBN 0-7803-7632-3.

- ^ Arora, Sanjeev; Barak, Boaz (2009). "Section 19.2.2". Computational Complexity: A Modern Approach. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42426-4.

- ^ Guruswami, Venkatesan (2009). List decoding of binary codes (PDF). p. 3.

- ^ Bose, Raj Chandra; Shrikhande, Sharadchandra Shankar (June 1959). "A note on a result in the theory of code construction". Information and Control. 2 (2): 183–194. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.154.2879. doi:10.1016/S0019-9958(59)90376-6.

- ^ Langton, Charan [at Wikidata] (2002). "CDMA Tutorial: Intuitive Guide to Principles of Communications" (PDF). Complex to Real. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2017-11-10.

- ^ Jaffe, David B.; Bouyukliev, Iliya. "Optimal binary linear codes of dimension at most seven". Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

Further reading

[edit]- Rudra, Atri. "Hamming code and Hamming bound" (PDF). Lecture notes.

- Rudolph, Dietmar; Rudolph, Matthias (2011-04-12). "46.4. Hadamard– oder Walsh–Codes". Modulationsverfahren (PDF) (in German). Cottbus, Germany: Brandenburg University of Technology (BTU). p. 214. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-16. Retrieved 2021-06-14. (xiv+225 pages)

Hadamard code

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

The Hadamard code is a linear error-correcting code over the finite field GF(2), specifically a binary linear code with parameters for a positive integer , where the length is , the dimension is , and the minimum Hamming distance is .[4] The codewords correspond to the evaluations of all possible inner products of a message vector with every vector . The encoding function is defined as , where the inner product .[4] For example, when , assuming the vectors are ordered lexicographically as , the codewords are (for ), (for ), (for ), and (for ); this forms a code.[4] An augmented version of the Hadamard code extends the dimension by including the all-ones vector, resulting in parameters while preserving the length and distance.[5] This augmentation can be achieved by incorporating the complements of the original codewords into the linear span.[5] The Hadamard code generalizes constructions based on Hadamard matrices, which provide orthogonal bases for higher-order variants.[5]Parameters

The Hadamard code is a binary linear code characterized by a block length of , where is both the dimension (number of information bits) and the parameter defining the code size. The minimum Hamming distance is , ensuring that any two distinct codewords differ in exactly half of the positions. All non-zero codewords have a constant Hamming weight of precisely . The coding rate is , which decreases exponentially with , reflecting the code's emphasis on high distance over information density. The relative distance remains constant across all , achieving optimality in the Plotkin bound for binary codes with relative distance at least . These parameters stem from the inner product construction, where each codeword corresponds to the parity-check evaluations of all possible vectors in .| Dimension | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 8 | 3 | 4 |

| 5 | 32 | 5 | 16 |

Historical Background

Origins in Hadamard Matrices

A Hadamard matrix of order is an square matrix whose entries are either or and satisfies the condition , where is the identity matrix.[6] This orthogonality condition implies that the rows (and similarly the columns) of are mutually orthogonal vectors in .[7] The Hadamard conjecture posits that such matrices exist for all positive integers or a multiple of 4.[6] Each row of has Euclidean norm , as the inner product of a row with itself is , and the inner product between any two distinct rows is 0, reflecting their perfect orthogonality.[7] An early example of constructing such matrices was provided by Sylvester in 1867 through a recursive doubling method.[6] In the context of coding theory, Hadamard matrices are often normalized to binary form by mapping entries of to 0 and to 1, yielding a matrix over the binary alphabet that preserves the underlying orthogonal structure for code generation.[3]Development and Early Applications

The foundations of Hadamard matrices, which underpin Hadamard codes, trace back to the work of English mathematician James Joseph Sylvester, who in 1867 introduced a doubling construction for generating such matrices from smaller ones, initially describing them as "anallagmatic pavements."[6] French mathematician Jacques Hadamard further advanced their study in 1893, proving a bound on the maximum determinant of these matrices with entries restricted to -1 and 1, which highlighted their orthogonal properties and laid the groundwork for later applications in coding theory.[6] These matrices transitioned from pure mathematics to practical error-correcting codes in the mid-20th century, as researchers recognized their utility in constructing binary codes with high minimum distance for reliable data transmission over noisy channels. A pivotal early application occurred in 1971 during NASA's Mariner 9 mission to Mars, where a [32,6,16] Hadamard code—derived from a 32×32 Hadamard matrix—was employed to encode telemetry data, including black-and-white images of the Martian surface, enabling correction of up to 7 errors per 32-bit codeword in the presence of deep-space noise.[8] This bi-orthogonal Reed-Muller code variant provided a coding gain of approximately 2.2 dB and was selected for its simplicity and effectiveness in low-rate image transmission.[8] Decoding was performed using specialized hardware known as the "Green Machine," which implemented the fast Walsh-Hadamard transform (FWHT) to efficiently compute correlations between received signals and codewords, achieving near-maximum-likelihood performance with minimal computational overhead.[9] Following the Mariner missions, Hadamard codes saw limited continued use in NASA deep-space telemetry through the 1980s, but their adoption declined post-1990s as convolutional codes, particularly rate-1/2 variants with Viterbi decoding, offered superior performance for higher data rates and became the standard in missions like Voyager (1977 onward).[10][8] Despite this shift in practical engineering applications, Hadamard codes endured in theoretical coding theory due to their optimal parameters and role in bounding constructions like the Plotkin bound.[11] They also relate briefly to Walsh codes, which adapt Hadamard matrices for orthogonal spreading in communication systems.[12]Constructions

Inner Product Construction

The Hadamard code can be constructed as the image of the evaluation map from the vector space of linear functions over to . Specifically, for each message vector , the corresponding codeword is given by , where denotes the inner product modulo 2. This yields a linear code of length and dimension , as the codewords are precisely the evaluations of all linear functions (including the zero function) over .[13] The generator matrix for this code is a matrix over whose columns are all distinct vectors in , ordered arbitrarily (e.g., in lexicographical order). A codeword for message is then , confirming the inner product interpretation. This matrix form directly implements the evaluation map, with each column corresponding to an evaluation point .[1] For , the length is and the generator matrix has 3 rows and 8 columns listing all 3-bit binary vectors as columns:| Column index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Row 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Row 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Generator Matrix Construction

The generator matrix of the Hadamard code admits a systematic form, with rows corresponding to basis vectors representing linear functions over the vector space and columns indexing all evaluation points in . For the basic Hadamard code of length and dimension , the generator matrix has entries equal to the -th bit of the binary representation of the index (for ), ensuring that codewords are evaluations of linear polynomials at these points.[14] This matrix arises from the recursive Sylvester construction of Hadamard matrices, which begins with H_1 = {{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=1&&&citation_type=wikipedia}} and proceeds as for , yielding a matrix of order with orthogonal rows of equal norm. To derive the binary generator matrix, map entries of by replacing with and with , then take the row space over ; the resulting code is generated by any linearly independent rows, such as those aligned with the coordinate functions in the systematic form above.[3] For the augmented Hadamard code, prepend or append an all-ones row to , extending the dimension to while preserving the length and incorporating an overall parity check; this yields the first-order Reed-Muller code .[15] Codewords in this construction are constant on the cosets of hyperplanes in , as each corresponds to the evaluation of an affine linear function, which remains invariant along translates of its kernel.[15] The inner product construction offers an equivalent perspective on the same code.[15]Hadamard Matrix Construction

A general construction of Hadamard codes utilizes an Hadamard matrix with entries in , where the rows of are pairwise orthogonal and each has norm . To form the code of length , construct the augmented matrix , whose rows are vectors in . Include the rows of the matrix to obtain a total of vectors. Map each entry via and to yield binary codewords in . This produces a constant-weight code with each codeword of weight and minimum Hamming distance , equivalent to a code in the nonlinear sense (with dimension approximately ).[15] The orthogonality of the rows in ensures that any two distinct vectors from the augmented set have inner product 0 over , leading to exactly positions of disagreement after the sign mapping, confirming the minimum distance . For orders that are powers of 2 via the Sylvester construction, this code is linear over with exact dimension . In general, the code's existence requires a Hadamard matrix of order , which is known to exist for and all multiples of 4 up to large values, per the Hadamard conjecture; constructions for non-power-of-two orders often rely on conference matrices, as a symmetric conference matrix of order yields a Hadamard matrix of order .[16][17] As an example, consider the Sylvester Hadamard matrix of order : The rows of and , after binary mapping, produce the 8 codewords of the Hadamard code, including vectors like , , and their complements in the set, matching the parameters of the power-of-two construction. This code corrects up to 1 error and detects up to 3.[15] When the order , puncturing this Hadamard code by removing the coordinate corresponding to the zero vector yields the simplex code of length , dimension , and distance , a maximal-distance linear code related to Reed-Muller codes.[15]Properties

Hamming Distance

The minimum Hamming distance of the Hadamard code is .[2] Since the code is linear over , this distance equals the minimum weight of any nonzero codeword.[2] For a nonzero codeword with , the weight is the number of positions where over .[2] The inner product defines a nontrivial linear functional on , which takes value 1 on exactly half the elements of the space, or positions, because the kernel of the functional has index 2.[2] For any two distinct codewords and , their sum is , where , so the Hamming distance is .[2] Equivalently, the codewords agree in exactly coordinates and differ in the remaining , as the linear functionals defined by and agree on a subspace of codimension 1.[2] The relative distance is thus .[2] This constant relative distance implies that the code can correct up to errors via nearest-neighbor decoding.[2] The following table illustrates the minimum distance relative to the block length for small values of :| 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 3 | 8 | 4 |

| 4 | 16 | 8 |

| 5 | 32 | 16 |

Duality and Weights

The Hadamard code is the subcode of the first-order Reed-Muller code RM(1,m) consisting of the evaluations of homogeneous linear functions over (i.e., without constant term). It is self-orthogonal for , satisfying . The dual code has dimension and can be described as the set of all vectors orthogonal to the linear functionals, which includes the constant functions and higher-degree terms in the Reed-Muller hierarchy.[18] The weight distribution of the Hadamard code is simple: all codewords have weight either 0 (the zero codeword) or , with no intermediate weights possible. There are exactly nonzero codewords, each of constant weight , which classifies the code as a constant-weight code for nonzero elements (two-weight including zero) and contributes to its optimality in certain detection scenarios. This uniform weight structure follows directly from the evaluation of linear functions over , where each nonzero linear function takes the value 1 on precisely half the input points.[2] A key property is the inner product between codewords. For distinct nonzero , the inner product satisfies which equals 0 modulo 2 for . For , it is for . This confirms self-orthogonality for . The Hadamard code has all even-weight codewords due to the balanced nature of the linear functions.[2]Decoding

Local Decodability

A -locally decodable code (LDC) is an error-correcting code that encodes a -bit message into an -bit codeword , such that for any position and any received word with (where denotes componentwise addition over ), there exists a randomized decoder that queries at most positions of and outputs with success probability at least .[19] The Hadamard code, which encodes a -bit message into an -bit codeword with coordinates indexed by vectors where (the inner product over ), is a -LDC for all .[20] This local decodability leverages the code's minimum Hamming distance of , enabling tolerance to error rates up to in the worst case. Lemma 1. For any non-zero , . Proof of Lemma 1. The inner product defines a non-constant linear functional on . Since is chosen uniformly at random, the distribution of is uniform over , yielding the stated probability. The proof of local decodability follows from the linearity of the code and properties of inner products. To recover the -th message bit (where is the -th standard basis vector), the decoder samples a uniform random , queries the received word at positions and , and outputs . If both positions are uncorrupted, then by linearity of the inner product. For any fixed error pattern with , the probability over that at least one queried position is corrupted is at most by the union bound, since each queried position is equally likely to be any coordinate. Thus, the success probability is at least , as required.[20][19]Decoding Algorithm

The local decoding algorithm for the Hadamard code enables recovery of the -th bit of the message from a noisy received word , where for and has Hamming weight at most with . This 2-query decoder, which underlies the Goldreich-Levin hardcore predicate, operates by selecting a random vector conditioned on and querying positions and , where is the -th standard basis vector. The output equals , so if and only if .[21] The query pairs with form a perfect matching of the hypercube, partitioning the positions into disjoint pairs differing only in the -th coordinate. For any fixed adversarial with , the fraction of pairs where exactly one position is corrupted (leading to failure) is at most , since each error affects exactly one pair. Thus, the worst-case success probability of a single trial is at least . For , this yields , with bias over random guessing. This can be amplified via repetition: perform independent trials and output the majority vote, succeeding with probability at least by standard concentration bounds (e.g., Chernoff). For constant (e.g., ) and fixed (constant ), ; more generally, for , and total queries are .[21] The algorithm requires queries per trial (hence total queries, constant for fixed ) and runs in polynomial time in , as each step involves -time operations for vector generation and XOR; the fast Walsh-Hadamard transform is unnecessary for this local procedure but enables global decoding in time if full recovery is desired.[21] Here is pseudocode for decoding the -th bit with amplification:function LocalDecode(r, i, s): // r: query access to received word, i: bit index, s: # repetitions

votes = [] // List to collect trial outputs

for j = 1 to s:

y = random vector in {0,1}^k with y_i = 1 // Uniform over 2^{k-1} choices

z = y ⊕ e_i // Flip i-th bit of y

r_y = query r at y

r_z = query r at z

a_hat = r_y ⊕ r_z

append a_hat to votes

return majority of votes // 0 if ≤ s/2 ones, else 1

function LocalDecode(r, i, s): // r: query access to received word, i: bit index, s: # repetitions

votes = [] // List to collect trial outputs

for j = 1 to s:

y = random vector in {0,1}^k with y_i = 1 // Uniform over 2^{k-1} choices

z = y ⊕ e_i // Flip i-th bit of y

r_y = query r at y

r_z = query r at z

a_hat = r_y ⊕ r_z

append a_hat to votes

return majority of votes // 0 if ≤ s/2 ones, else 1

Advanced Topics

Optimality

The Hadamard code of length and dimension achieves a minimum distance , corresponding to relative distance . This meets the Plotkin bound with equality for binary codes attaining these parameters, as the bound states that , and the code's size saturates the bound in the linear setting for this dimension. For , the Hadamard code is the unique (up to equivalence) optimal linear binary code with parameters , meaning no other linear code of the same length and dimension achieves a larger distance, by classification results on equidistant linear codes via Bonisoli's theorem. For larger , the Hadamard code remains near-optimal but can be outperformed in tradeoffs between rate and distance by advanced constructions, such as algebraic-geometric codes that achieve superior parameters for certain high-rate regimes over finite fields. In the context of locally decodable codes (LDCs), the Hadamard code serves as an optimal 2-query LDC for constant relative distance , with decoding radius up to for any . Its length matches the information-theoretic lower bound of up to constant factors, establishing it as asymptotically optimal among 2-query linear LDCs. To illustrate optimality for small dimensions, the following table compares the Hadamard code with the Hamming code (binary) and Reed-Solomon code (non-binary, over ) for comparable small lengths:| Code | Length | Dimension | Distance | Rate | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hadamard () | 8 | 3 | 4 | 0.375 | 0.5 |

| Extended Hamming | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Hamming () | 7 | 4 | 3 | ≈0.571 | ≈0.429 |

| Reed-Solomon | 7 | 4 | 4 | ≈0.571 | ≈0.571 |

![{\displaystyle [2^{k},k,2^{k-1}]_{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4c61084e4ec593311b8d2e834afabf4d432a1916)

![{\displaystyle [2^{k},k+1,2^{k-1}]_{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/33dd8f1c5efa897cd15747ab8be5b594038db3af)

![{\displaystyle \Pr _{y\in \{0,1\}^{k}}{\big [}({\text{Had}}(x))_{y}=1{\big ]}=\Pr _{y\in \{0,1\}^{k}}{\big [}\langle x,y\rangle =1{\big ]}\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/06608d6f4e85e02437feadfee966819b06cefd0b)

![{\displaystyle Pr[D(y)_{i}=x_{i}]\geq {\frac {1}{2}}+\epsilon ,\forall i\in [k]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e32fc2f85a3ba5f7a3583457ef5ebf38830a2d00)