Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Turbo code

View on WikipediaIn information theory, turbo codes are a class of high-performance forward error correction (FEC) codes developed around 1990–91, but first published in 1993. They were the first practical codes to closely approach the maximum channel capacity or Shannon limit, a theoretical maximum for the code rate at which reliable communication is still possible given a specific noise level. Turbo codes are used in 3G/4G mobile communications (e.g., in UMTS and LTE) and in (deep space) satellite communications as well as other applications where designers seek to achieve reliable information transfer over bandwidth- or latency-constrained communication links in the presence of data-corrupting noise. Turbo codes compete with low-density parity-check (LDPC) codes, which provide similar performance. Until the patent for turbo codes expired,[1] the patent-free status of LDPC codes was an important factor in LDPC's continued relevance.[2]

The name "turbo code" arose from the feedback loop used during normal turbo code decoding, which was analogized to the exhaust feedback used for engine turbocharging. Hagenauer has argued the term turbo code is a misnomer since there is no feedback involved in the encoding process.[3]

History

[edit]The fundamental patent application for turbo codes was filed on 23 April 1991. The patent application lists Claude Berrou as the sole inventor of turbo codes. The patent filing resulted in several patents including US Patent 5,446,747, which expired 29 August 2013.

The first public paper on turbo codes was "Near Shannon Limit Error-correcting Coding and Decoding: Turbo-codes".[4] This paper was published 1993 in the Proceedings of IEEE International Communications Conference. The 1993 paper was formed from three separate submissions that were combined due to space constraints. The merger caused the paper to list three authors: Berrou, Glavieux, and Thitimajshima (from Télécom Bretagne, former ENST Bretagne, France). However, it is clear from the original patent filing that Berrou is the sole inventor of turbo codes and that the other authors of the paper contributed material other than the core concepts.[improper synthesis]

Turbo codes were so revolutionary at the time of their introduction that many experts in the field of coding did not believe the reported results. When the performance was confirmed a small revolution in the world of coding took place that led to the investigation of many other types of iterative signal processing.[5]

The first class of turbo code was the parallel concatenated convolutional code (PCCC). Since the introduction of the original parallel turbo codes in 1993, many other classes of turbo code have been discovered, including serial concatenated convolutional codes and repeat-accumulate codes. Iterative turbo decoding methods have also been applied to more conventional FEC systems, including Reed–Solomon corrected convolutional codes, although these systems are too complex for practical implementations of iterative decoders. Turbo equalization also flowed from the concept of turbo coding.

In addition to turbo codes, Berrou also invented recursive systematic convolutional (RSC) codes, which are used in the example implementation of turbo codes described in the patent. Turbo codes that use RSC codes seem to perform better than turbo codes that do not use RSC codes.

Prior to turbo codes, the best constructions were serial concatenated codes based on an outer Reed–Solomon error correction code combined with an inner Viterbi-decoded short constraint length convolutional code, also known as RSV codes.

In a later paper, Berrou gave credit to the intuition of "G. Battail, J. Hagenauer and P. Hoeher, who, in the late 80s, highlighted the interest of probabilistic processing." He adds "R. Gallager and M. Tanner had already imagined coding and decoding techniques whose general principles are closely related," although the necessary calculations were impractical at that time.[6]

An example encoder

[edit]There are many different instances of turbo codes, using different component encoders, input/output ratios, interleavers, and puncturing patterns. This example encoder implementation describes a classic turbo encoder, and demonstrates the general design of parallel turbo codes.

This encoder implementation sends three sub-blocks of bits. The first sub-block is the m-bit block of payload data. The second sub-block is n/2 parity bits for the payload data, computed using a recursive systematic convolutional code (RSC code). The third sub-block is n/2 parity bits for a known permutation of the payload data, again computed using an RSC code. Thus, two redundant but different sub-blocks of parity bits are sent with the payload. The complete block has m + n bits of data with a code rate of m/(m + n). The permutation of the payload data is carried out by a device called an interleaver.

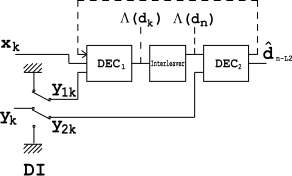

Hardware-wise, this turbo code encoder consists of two identical RSC coders, C1 and C2, as depicted in the figure, which are connected to each other using a concatenation scheme, called parallel concatenation:

In the figure, M is a memory register. The delay line and interleaver force input bits dk to appear in different sequences. At first iteration, the input sequence dk appears at both outputs of the encoder, xk and y1k or y2k due to the encoder's systematic nature. If the encoders C1 and C2 are used in n1 and n2 iterations, their rates are respectively equal to

The decoder

[edit]The decoder is built in a similar way to the above encoder. Two elementary decoders are interconnected to each other, but in series, not in parallel. The decoder operates on lower speed (i.e., ), thus, it is intended for the encoder, and is for correspondingly. yields a soft decision which causes delay. The same delay is caused by the delay line in the encoder. The 's operation causes delay.

An interleaver installed between the two decoders is used here to scatter error bursts coming from output. DI block is a demultiplexing and insertion module. It works as a switch, redirecting input bits to at one moment and to at another. In OFF state, it feeds both and inputs with padding bits (zeros).

Consider a memoryless AWGN channel, and assume that at k-th iteration, the decoder receives a pair of random variables:

where and are independent noise components having the same variance . is a k-th bit from encoder output.

Redundant information is demultiplexed and sent through DI to (when ) and to (when ).

yields a soft decision; i.e.:

and delivers it to . is called the logarithm of the likelihood ratio (LLR). is the a posteriori probability (APP) of the data bit which shows the probability of interpreting a received bit as . Taking the LLR into account, yields a hard decision; i.e., a decoded bit.

It is known that the Viterbi algorithm is unable to calculate APP, thus it cannot be used in . Instead of that, a modified BCJR algorithm is used. For , the Viterbi algorithm is an appropriate one.

However, the depicted structure is not an optimal one, because uses only a proper fraction of the available redundant information. In order to improve the structure, a feedback loop is used (see the dotted line on the figure).

Soft decision approach

[edit]The decoder front-end produces an integer for each bit in the data stream. This integer is a measure of how likely it is that the bit is a 0 or 1 and is also called soft bit. The integer could be drawn from the range [−127, 127], where:

- −127 means "certainly 0"

- −100 means "very likely 0"

- 0 means "it could be either 0 or 1"

- 100 means "very likely 1"

- 127 means "certainly 1"

This introduces a probabilistic aspect to the data-stream from the front end, but it conveys more information about each bit than just 0 or 1.

For example, for each bit, the front end of a traditional wireless-receiver has to decide if an internal analog voltage is above or below a given threshold voltage level. For a turbo code decoder, the front end would provide an integer measure of how far the internal voltage is from the given threshold.

To decode the m + n-bit block of data, the decoder front-end creates a block of likelihood measures, with one likelihood measure for each bit in the data stream. There are two parallel decoders, one for each of the n⁄2-bit parity sub-blocks. Both decoders use the sub-block of m likelihoods for the payload data. The decoder working on the second parity sub-block knows the permutation that the coder used for this sub-block.

Solving hypotheses to find bits

[edit]The key innovation of turbo codes is how they use the likelihood data to reconcile differences between the two decoders. Each of the two convolutional decoders generates a hypothesis (with derived likelihoods) for the pattern of m bits in the payload sub-block. The hypothesis bit-patterns are compared, and if they differ, the decoders exchange the derived likelihoods they have for each bit in the hypotheses. Each decoder incorporates the derived likelihood estimates from the other decoder to generate a new hypothesis for the bits in the payload. Then they compare these new hypotheses. This iterative process continues until the two decoders come up with the same hypothesis for the m-bit pattern of the payload, typically in 15 to 18 cycles.

An analogy can be drawn between this process and that of solving cross-reference puzzles like crossword or sudoku. Consider a partially completed, possibly garbled crossword puzzle. Two puzzle solvers (decoders) are trying to solve it: one possessing only the "down" clues (parity bits), and the other possessing only the "across" clues. To start, both solvers guess the answers (hypotheses) to their own clues, noting down how confident they are in each letter (payload bit). Then, they compare notes, by exchanging answers and confidence ratings with each other, noticing where and how they differ. Based on this new knowledge, they both come up with updated answers and confidence ratings, repeating the whole process until they converge to the same solution.

Performance

[edit]Turbo codes perform well due to the attractive combination of the code's random appearance on the channel together with the physically realisable decoding structure. Turbo codes are affected by an error floor.

Practical applications using turbo codes

[edit]Telecommunications:

- Turbo codes are used extensively in 3G and 4G mobile telephony standards; e.g., in HSPA, EV-DO and LTE.

- MediaFLO, terrestrial mobile television system from Qualcomm.

- The interaction channel of satellite communication systems, such as DVB-RCS[7] and DVB-RCS2.

- Recent NASA missions such as Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter use turbo codes as an alternative to Reed–Solomon error correction-Viterbi decoder codes.

- IEEE 802.16 (WiMAX), a wireless metropolitan network standard, uses block turbo coding and convolutional turbo coding.

Bayesian formulation

[edit]From an artificial intelligence viewpoint, turbo codes can be considered as an instance of loopy belief propagation in Bayesian networks.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ US 5446747

- ^ Erico Guizzo (1 March 2004). "CLOSING IN ON THE PERFECT CODE". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. "Another advantage, perhaps the biggest of all, is that the LDPC patents have expired, so companies can use them without having to pay for intellectual-property rights."

- ^ Hagenauer, Joachim; Offer, Elke; Papke, Luiz (March 1996). "Iterative Decoding of Binary Block and Convolutional Codes" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 42 (2): 429–445. doi:10.1109/18.485714. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ Berrou, Claude; Glavieux, Alain; Thitimajshima, Punya (1993), "Near Shannon Limit Error – Correcting", Proceedings of IEEE International Communications Conference, vol. 2, pp. 1064–70, doi:10.1109/ICC.1993.397441, S2CID 17770377, retrieved 11 February 2010

- ^ Erico Guizzo (1 March 2004). "CLOSING IN ON THE PERFECT CODE". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023.

- ^ Berrou, Claude, The ten-year-old turbo codes are entering into service, Bretagne, France, retrieved 11 February 2010

- ^ Digital Video Broadcasting (DVB); Interaction channel for Satellite Distribution Systems, ETSI EN 301 790, V1.5.1, May 2009.

- ^ McEliece, Robert J.; MacKay, David J. C.; Cheng, Jung-Fu (1998), "Turbo decoding as an instance of Pearl's "belief propagation" algorithm" (PDF), IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, 16 (2): 140–152, doi:10.1109/49.661103, ISSN 0733-8716.

Further reading

[edit]Publications

[edit]- Battail, Gérard (1998). "A conceptual framework for understanding turbo codes". IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications. 916 (2): 245–254. doi:10.1109/49.661112.

- Brejza, M.F.; Li, L.; Maunder, R.G.; Al-Hashimi, B.M.; Berrou, C.; Hanzo, L. (2016). "20 years of turbo coding and energy-aware design guidelines for energy-constrained wireless applications" (PDF). IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. 918 (1): 8–28. doi:10.1109/COMST.2015.2448692. S2CID 12966388.

- Garzón-Bohórquez, Ronald; Nour, Charbel Abdel; Douillard, Catherine (2016). Improving Turbo codes for 5G with parity puncture-constrained interleavers (PDF). 9th International Symposium on Turbo Codes and Iterative Information Processing (ISTC). pp. 151–5. doi:10.1109/ISTC.2016.7593095.

External links

[edit]- Guizzo, Erico (March 2004). "Closing In On The Perfect Code". IEEE Spectrum. 41 (3): 36–42. doi:10.1109/MSPEC.2004.1270546. S2CID 21237188. Archived from the original on 11 October 2009.

- "The UMTS Turbo Code and an Efficient Decoder Implementation Suitable for Software-Defined Radios" Archived 20 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine (International Journal of Wireless Information Networks)

- Mackenzie, Dana (2005). "Take it to the limit". New Scientist. 187 (2507): 38–41.

- "Pushing the Limit", a Science News feature about the development and genesis of turbo codes

- International Symposium On Turbo Codes

- Coded Modulation Library, an open source library for simulating turbo codes in matlab

- "Turbo Equalization: Principles and New Results" Archived 27 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, an IEEE Transactions on Communications article about using convolutional codes jointly with channel equalization.

- IT++ Home Page The IT++ is a powerful C++ library which in particular supports turbo codes

- Turbo codes publications by David MacKay

- AFF3CT Home Page (A Fast Forward Error Correction Toolbox) for high speed turbo codes simulations in software

- Kerouédan, Sylvie; Berrou, Claude (2010). "Turbo code". Scholarpedia. 5 (4). scholarpedia.org: 6496. Bibcode:2010SchpJ...5.6496K. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.6496.

- 3GPP LTE Turbo Reference Design.

- Estimate Turbo Code BER Performance in AWGN Archived 1 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine (MatLab).

- Parallel Concatenated Convolutional Coding: Turbo Codes (MatLab Simulink)

Turbo code

View on GrokipediaHistory and Development

Invention and Early Milestones

Turbo codes were invented in 1993 by Claude Berrou, Alain Glavieux, and Punya Thitimajshima while working at the École Nationale Supérieure des Télécommunications de Bretagne (ENST Bretagne), now known as IMT Atlantique, in France. Their breakthrough involved parallel concatenation of convolutional codes with iterative decoding, marking a significant advancement in error-correcting codes capable of approaching theoretical limits. This development stemmed from research into high-performance coding schemes for reliable data transmission over noisy channels.[1] The invention was first publicly disclosed in a seminal conference paper presented at the 1993 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC '93) in Geneva, Switzerland, titled "Near Shannon Limit Error-Correcting Coding and Decoding: Turbo-Codes." In this paper, the authors demonstrated through simulations that turbo codes could achieve a bit error rate (BER) of 10^{-5} at an E_b/N_0 of approximately 0.7 dB for a rate-1/2 code, placing performance within 0.5 dB of the pragmatic Shannon limit for binary input additive white Gaussian noise channels. These results highlighted the codes' potential to operate near the theoretical capacity bound, outperforming conventional convolutional codes by several decibels.[1] Early milestones in turbo code adoption followed swiftly, reflecting their rapid recognition in telecommunications standards. By 1999, turbo codes were selected for forward error correction in the Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS), the 3G mobile standard developed by the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), enabling efficient data services at rates up to 2 Mbps. These adoptions solidified turbo codes as a cornerstone of modern wireless and broadcast systems.Key Contributors and Publications

The development of turbo codes is primarily attributed to Claude Berrou, a French professor and researcher at the École Nationale Supérieure des Télécommunications de Bretagne (ENST Bretagne, now part of IMT Atlantique), who conceived the core idea of parallel concatenated convolutional codes in 1991 while exploring iterative decoding techniques for error correction.[7] The fundamental patent application was filed on April 23, 1991, listing Berrou as the sole inventor.[8] Berrou served as the lead inventor, focusing on the integration of recursive systematic convolutional encoders with interleaving to achieve near-Shannon-limit performance, and he is listed as the sole inventor on the foundational patents.[9] His collaborator Alain Glavieux, also at ENST Bretagne and Berrou's long-term research partner until Glavieux's passing in 2003, contributed to the theoretical refinement of the decoding algorithm, particularly the iterative exchange of extrinsic information between component decoders.[10] Punya Thitimajshima, a Thai doctoral student under Berrou's supervision at ENST Bretagne from 1989 to 1993, played a key role in analyzing recursive systematic convolutional codes, which became essential to the turbo code structure; his thesis work directly informed the encoder design and earned him co-authorship on seminal publications.[7] The foundational publication introducing turbo codes was the 1993 paper "Near Shannon limit error-correcting coding and decoding: Turbo-codes" by Berrou, Glavieux, and Thitimajshima, presented at the IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC '93) in Geneva, Switzerland, where it demonstrated bit error rates approaching 10^{-5} at 0.7 dB E_b/N_0 for a coding rate of 1/2, within 0.5 dB of the Shannon limit.[1] This work was expanded in the 1996 journal article "Near Optimum Error Correcting Coding and Decoding: Turbo-codes" by Berrou and Glavieux, published in IEEE Transactions on Communications, which provided detailed derivations of the maximum a posteriori (MAP) decoding components and confirmed the codes' efficiency through simulations.[11] Patent filings followed, with France Télécom (now Orange) securing ownership of the intellectual property; notable examples include US Patent 5,446,747 (filed 1993, granted 1995) for the parallel concatenation method and related encoding/decoding processes, enabling commercial licensing for wireless standards. ENST Bretagne, located in Brest, France, served as the primary institution for turbo code development, where Berrou led a research team funded partly by France Télécom to address error correction challenges in satellite and mobile communications during the early 1990s.[12] The institution's electronics department fostered interdisciplinary work on convolutional coding and iterative processing, culminating in the turbo code breakthrough; today, as IMT Atlantique, it continues research on advanced error-correcting codes, building on this legacy.[13] Turbo codes exerted profound influence on coding theory, with the 1993 ICC paper garnering over 5,000 citations and inspiring extensions like the "turbo principle" of iterative information exchange across modules.[14] A notable extension came from Joachim Hagenauer at the Technical University of Munich, who in 1996 introduced turbo equalization by applying the iterative decoding paradigm to joint channel equalization and decoding, as detailed in his work on MAP equalization for intersymbol interference channels, which improved performance in dispersive environments and amassed hundreds of citations.[15]Fundamentals

Basic Principles

Turbo codes represent a class of iterative error-correcting codes known as parallel concatenated convolutional codes (PCCCs), which achieve bit error rates close to the Shannon limit—typically within 0.5 dB for moderate code rates—through a combination of code concatenation and soft iterative decoding. Introduced as a breakthrough in forward error correction, these codes leverage redundancy generated by multiple encoders to approach theoretical channel capacity limits in additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) channels.[16] The fundamental idea behind turbo codes is the parallel concatenation of two or more constituent convolutional encoders, separated by a pseudo-random interleaver, to produce independent parity sequences that collectively improve error detection and correction. This structure exploits the diversity of errors across permuted data streams, enabling the iterative exchange of soft information during decoding to refine estimates of the transmitted bits. The use of recursive systematic convolutional (RSC) encoders as constituents is key, as their feedback loops enhance performance at low signal-to-noise ratios by amplifying the effect of input errors.[16] To understand turbo codes, familiarity with convolutional codes is essential; these are linear time-invariant codes characterized by a trellis structure that models state transitions over time and defined by generator polynomials, which specify the connections in a shift-register-based encoder using modulo-2 addition.[17] For example, a rate-1/2 convolutional code might use polynomials such as and , where represents a delay element, producing output bits as linear combinations of input and memory elements. Interleaving serves as a permutation mechanism that rearranges the input sequence to decorrelate burst errors or correlated noise, ensuring that the parity outputs from different encoders address distinct error patterns and thereby increasing the effective minimum distance of the code.[16] In terms of overall architecture, turbo encoders produce a systematic output comprising the original information bits alongside parity bits generated independently by each constituent encoder, allowing the decoder to directly access the data while using the parities for reliability verification during iterations. This punctured or rate-matched output format balances coding gain with transmission efficiency, typically yielding code rates around 1/3 for dual-encoder configurations.[16]Constituent Codes and Interleaving

Turbo codes utilize two identical recursive systematic convolutional (RSC) codes as their constituent encoders, which generate both systematic and parity outputs while incorporating feedback for enhanced error-correcting performance. Each RSC encoder operates with a constraint length of (memory ), defined by a feedback polynomial (octal 15) and a feedforward polynomial (octal 13). These polynomials ensure a primitive feedback structure that promotes long error events and improves the code's distance properties during iterative decoding. The interleaver serves as a critical component between the two constituent encoders, permuting the input bits to the second RSC encoder to decorrelate the parity outputs and maximize the Hamming distance between erroneous bit patterns. This randomization prevents low-weight codewords from aligning in both encoders, thereby boosting the overall minimum distance of the turbo code. Typical interleaver designs include S-random interleavers, which enforce a minimum separation (often set to to times the constraint length) between the original and permuted positions of any bit to avoid short cycles, and simpler block interleavers that rearrange bits in row-column fashion for efficient hardware implementation. The interleaver length matches the information block size to ensure full coverage without truncation. To achieve desired code rates higher than the native 1/3, puncturing selectively removes certain parity bits from the concatenated output while preserving all systematic bits. For instance, transitioning from rate 1/3 to 1/2 involves transmitting every systematic bit along with alternating parity bits from the first and second encoders, effectively halving the parity overhead without significantly degrading performance at moderate signal-to-noise ratios. This technique maintains near-optimum bit error rates by balancing rate and reliability. For encoding finite-length blocks, termination is applied to each constituent encoder by appending tail bits, computed as the systematic bits that drive the shift register back to the all-zero state. This trellis termination ensures known starting and ending states for the decoder, reducing edge effects and enhancing decoding reliability, though it incurs a small rate loss of approximately .Encoding Process

Parallel Concatenated Structure

The parallel concatenated structure forms the core architecture of the original turbo code, utilizing two identical recursive systematic convolutional (RSC) encoders arranged in parallel to process the input information bits. The input bit sequence, denoted as {u_k}, is directly fed into the first RSC encoder, which generates a systematic output stream X equal to the input itself and a corresponding parity output stream Y_1. Simultaneously, a permuted (interleaved) version of the input sequence is provided to the second RSC encoder, which produces an additional parity output stream Y_2. The overall coded output consists of the three streams—X, Y_1, and Y_2—resulting in a fundamental code rate of 1/3, where each input bit generates three output bits.[18] In a typical block diagram representation, the serial input bit stream enters the system and branches to the first encoder without modification, while a pseudo-random interleaver reorders the bits before directing them to the second encoder, ensuring decorrelation between the parity streams. The outputs from both encoders are then multiplexed into a single coded sequence for transmission, with the interleaver size typically matching the input block length to maintain efficiency. This parallel configuration allows the encoders to operate concurrently, simplifying hardware implementation by sharing a common clock frequency.[18] To achieve higher code rates beyond 1/3, such as 1/2 commonly used in practical systems, puncturing is applied by systematically deleting specific bits from the Y_1 and Y_2 streams according to predefined patterns, reducing redundancy without altering the encoder structure. The unpunctured rate-1/3 form preserves maximum error-correcting capability for low-rate applications. A key advantage of this parallel setup lies in its facilitation of extrinsic information exchange between the constituent decoders during subsequent processing, enabling iterative refinement that approaches the Shannon limit for error correction.[18][19]Example Encoder Implementation

To illustrate the encoding process of a turbo code, consider a simple setup with a block length of information bits, using two identical recursive systematic convolutional (RSC) encoders each with constraint length and generator polynomials for the feedback path and for the parity output.[20] An S-random interleaver is employed between the encoders to permute the input sequence and enhance error-spreading properties. For this example, termination tail bits are omitted to focus on the core process, yielding a rate-1/3 codeword of 24 bits without puncturing. The input information sequence is . This is fed directly into the first RSC encoder, which produces the systematic output and the parity output . The state of the encoder is represented by the two memory elements (initially [0, 0]), and computations are performed modulo 2. The step-by-step encoding for the first RSC is as follows:- Input bit 1 (): Feedback input , parity , new state [1, 0].

- Input bit 2 (): , , new state [1, 1].

- Input bit 3 (): , , new state [1, 1].

- Input bit 4 (): , , new state [1, 1].

- Input bit 5 (): , , new state [0, 1].

- Input bit 6 (): , , new state [1, 0].

- Input bit 7 (): , , new state [0, 1].

- Input bit 8 (): , , new state [1, 0].

- Input bit 1 (): , , new state [0, 0].

- Input bit 2 (): , , new state [1, 0].

- Input bit 3 (): , , new state [1, 1].

- Input bit 4 (): , , new state [0, 1].

- Input bit 5 (): , , new state [0, 0].

- Input bit 6 (): , , new state [1, 0].

- Input bit 7 (): , , new state [1, 1].

- Input bit 8 (): , , new state [1, 1].

| Sequence | Bits |

|---|---|

| Input | 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 |

| Systematic | 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 |

| Parity (first encoder) | 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 |

| Interleaved | 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 |

| Parity (second encoder) | 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 |

| Codeword | 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 |