Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

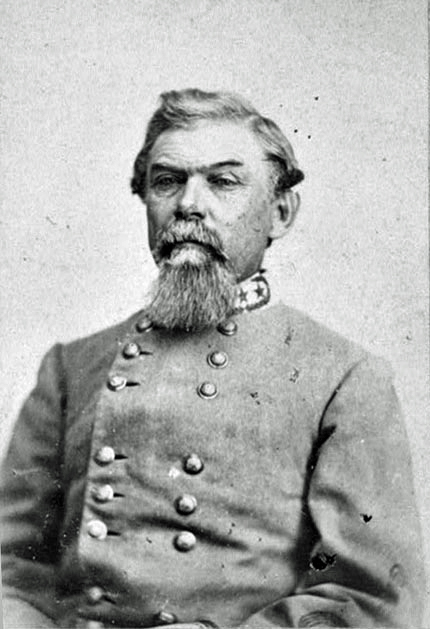

William J. Hardee

View on Wikipedia

Lieutenant-General William Joseph Hardee (October 12, 1815 – November 6, 1873) was an American military officer. He served in the United States Army in both the Second Seminole War and in the Mexican–American War. He was later commissioned as a general in the Confederate States Army in 1861. Hardee saw combat in the Western Theater of the American Civil War and was known to quarrel sharply with two of his commanding officers, Braxton Bragg and John Bell Hood. He later served in the Atlanta campaign of 1864 and the Carolinas campaign of 1865, where he surrendered with Joseph E. Johnston to the Union side led by William Tecumseh Sherman in April. Hardee's writings about military tactics were widely used on both sides in the conflict.

Key Information

Early life and career

[edit]Hardee was born to Sarah Ellis and Major John Hais Hardee Jr. at the Rural Felicity Plantation in Camden County, Georgia.[1] One of his brothers was noted Savannah merchant Noble Hardee.[2] He graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1838 (26th in a class of 45) and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Dragoons.[3] During the Seminole Wars (1835–42), he was stricken with illness, and while hospitalized he met and married Elizabeth Dummett. After he recovered, the Army sent him to France to study military tactics in 1840.[4] He was promoted to first lieutenant in 1839 and to captain in 1844.

In the Mexican–American War, Hardee served in the Army of Occupation under Zachary Taylor and won two brevet promotions (to brevet major for Medelin and Vera Cruz, and to lieutenant colonel for St. Augustin). He served with the 2nd U.S. Dragoons, and was second in command to Seth Thornton, when they were ambushed and surrounded by Mexican troops and subsequently captured on April 25, 1846, at Carricitos Ranch, Texas, during the "Thornton Affair". He was exchanged on May 11.[3] Now serving under Winfield Scott, Hardee was wounded in a skirmish at La Rosia, Mexico (about 30 miles (48 km) above Matamoros) in 1847.[4] After the war, he led units of Texas Rangers and soldiers in Texas.

After his wife died in 1853, he returned to West Point as a tactics instructor and served as commandant of cadets from 1856 to 1860. He served as the senior major in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry (later renumbered as the 5th U.S. Cavalry) when that regiment was formed in 1855 and then as the lieutenant colonel of the 1st U.S. Cavalry in 1860.[3] In 1855 at the behest of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, Hardee published Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics for the Exercise and Manoeuvres of Troops When Acting as Light Infantry or Riflemen, popularly known as Hardee's Tactics, which became the best-known drill manual of the Civil War.[5] He is also said to have designed the so-called Hardee hat about this time.

American Civil War

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

Hardee resigned his U.S. Army commission on January 31, 1861,[3] after his home state of Georgia seceded from the Union. He joined the Confederate States Army as a colonel on March 7 and was given command of Forts Morgan and Gaines in Alabama. He was subsequently promoted to brigadier general (June 17) and major general (October 7). By October 10, 1862, he was one of the first Confederate lieutenant generals.[3]

His initial assignment as a general was to organize a brigade of Arkansas regiments and he impressed his men and fellow officers by solving difficult supply problems and for the thorough training he gave his brigade. He received his nickname, "Old Reliable", while with this command. Hardee operated in Arkansas until he was called to join General Albert Sidney Johnston's Army of Central Kentucky as a corps commander. Johnston would withdraw from Kentucky and Tennessee, into Mississippi, before launching a surprise attack at the Battle of Shiloh in the spring of 1862. Hardee was wounded in the arm on April 6, 1862, during the first day of the battle.[3]

Johnston was killed at Shiloh and Hardee's corps joined General Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee prior to the Siege of Corinth, Mississippi, until Department Commander P.G.T. Beauregard evacuated the town and withdrew to Tupelo. Beauregard was replaced by Bragg, who subsequently moved his army to Chattanooga before embarking on his Confederate Heartland Offensive into Kentucky. That campaign concluded with the Battle of Perryville in October 1862, where Hardee commanded the Left Wing of Bragg's army.

In arguably his most successful battle, at the Battle of Stones River that December, his Second Corps launched a massive surprise assault upon the right flank of Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans's army, driving it almost to defeat, but again, as had happened at Perryville, Bragg failed to follow up his tactical success, opting instead to withdraw before the arrival of Union reinforcements.

After the Tullahoma Campaign, Hardee lost patience with the irascible, retreating Bragg and briefly commanded the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana under General Joseph E. Johnston. During this period, he met Mary Foreman Lewis, an Alabama plantation owner, whom he would later marry in January 1864.

Hardee returned to Bragg's army after the Battle of Chickamauga, taking over the corps of Leonidas Polk at Chattanooga, Tennessee, besieging the Union Army there. During the Chattanooga campaign in November 1863, Hardee's Corps of the Army of Tennessee was defeated when Union troops under Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas assaulted their seemingly impregnable defensive lines at the Battle of Missionary Ridge.

Hardee renewed his opposition to serving under Bragg and joined a group of officers who finally convinced Confederate President Jefferson Davis to relieve Bragg. Hardee was given temporary command of the Army of Tennessee before Joseph E. Johnston took over command at Dalton, Georgia. In February 1864, Johnston was ordered by the President to dispatch Hardee to Alabama, to reinforce General Polk against General Sherman's Meridian Campaign.

Following Sherman's withdrawal to Vicksburg, Hardee was once again sent back to Georgia, where he joined Johnston's army for the Atlanta campaign. As Johnston fought a war of maneuver and retreat against Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, the Confederacy eventually lost patience with him and replaced him with the much more aggressive Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood. Hardee could not abide Hood's reckless assaults and heavy casualties. After the Battle of Jonesboro that August and September, he requested a transfer and was sent to command the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. He opposed Sherman's March to the Sea as best he could with inadequate forces, eventually evacuating Savannah, Georgia on December 20.[4]

As Sherman turned north in the Carolinas campaign, Hardee took part in the Battle of Bentonville, North Carolina, in March 1865, where his only son, 16-year-old Willie, was mortally wounded in a cavalry charge.[7] Johnston's plan for Bentonville was for Hardee to engage one of Sherman's wings at Averasborough so that Johnston could deal with one wing piecemeal. The plan was unsuccessful. He surrendered along with Johnston to Sherman on April 26 at Durham Station.

Later life and death

[edit]After the war, Hardee settled at his wife's Alabama plantation. After returning it to working condition, the family moved to Selma, Alabama, where Hardee worked in the warehousing and insurance businesses. He eventually became president of the Selma and Meridian Railroad. Hardee was the co-author of The Irish in America, published in 1868. He fell ill at his family's summer retreat at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, and died in Wytheville, Virginia on November 6, 1873. He is buried in Live Oak Cemetery, Selma, Alabama.[3]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Mesch, Allen H. (2018). Preparing for Disunion: West Point Commandants and the Training of Civil War Leaders. McFarland Publishers. p. 122. ISBN 9781476674254.

- ^ Parker, James (July 30, 1975). "The Life of Noble Andrew Hardee". Savannah Biographies.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eicher, p. 279.

- ^ a b c Dupuy, p. 315.

- ^ Dupuy, p. 315: "...his tactical manual was used extensively by both armies in the Civil War."

- ^ "Hal Jespersen's 2013 Civil War Travelogues, Charleston and Savannah".

- ^ Bradley, pp. 382–83.

References

[edit]- Bradley, Mark L. Last Stand in the Carolinas: The Battle of Bentonville. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing Co., 1995. ISBN 1-882810-02-3.

- Dupuy, Trevor N., Curt Johnson, and David L. Bongard. Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. ISBN 978-0-06-270015-5.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 0-8071-0823-5.

- New Georgia Encyclopedia biography Archived December 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

[edit]- Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs Jr. General Willam J. Hardee: Old Reliable. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8071-1802-8. First published 1965.

External links

[edit]- Military biography of William J. Hardee from the Cullum biographies

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 941.

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Hardee Hall historical marker

- William J. Hardee at Find a Grave

William J. Hardee

View on GrokipediaWilliam Joseph Hardee (October 12, 1815 – November 6, 1873) was a career U.S. Army officer who resigned his commission to serve as a lieutenant general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, best known for authoring Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics (1855), the standard drill manual for the U.S. Army that was widely adopted by both Union and Confederate forces.[1][2] Born in Liberty County, Georgia, Hardee graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1838, ranking 26th in his class of 42, and participated in the Second Seminole War and the Mexican-American War, earning brevet promotions to captain and major for gallantry at Contreras and Churubusco.[1][3] Hardee's tactical manual emphasized maneuvers for rifle-armed infantry, drawing from European models like those of French General Silas Casey, and it remained influential throughout the Civil War era due to its detailed instructions on formations, firing, and light infantry operations.[2][4] In early 1861, following Georgia's secession, he resigned from the U.S. Army and was appointed a brigadier general in the Confederate forces, quickly rising to command roles in Arkansas where he organized state troops before transferring to the Army of Tennessee.[3][1] During the war, Hardee earned the nickname "Old Reliable" for his consistent tactical proficiency under generals like Albert Sidney Johnston, Braxton Bragg, and Joseph E. Johnston, participating in major engagements including Shiloh, Perryville, Stones River, Chickamauga, the Atlanta Campaign, and the Carolinas Campaign, where he conducted a successful delaying action at Averasboro before surrendering with Johnston's army in April 1865.[1][5] After the war, he worked as a cotton merchant and planter in Georgia and Alabama, avoiding politics and focusing on business until his death from illness in Selma.[1]

Early Life and Education

Family Background and Upbringing

William Joseph Hardee was born on October 12, 1815, at Rural Felicity, the family's plantation in Camden County, Georgia, located between Savannah and Jacksonville.[6] He was the youngest of seven children of Major John Hardee, a planter and slaveholder who served as a Georgia state senator, and Sarah Ellis Hardee.[3][7][1] The Hardee family background reflected the planter class of coastal Georgia, with John's military title likely stemming from service in the War of 1812 or state militia duties.[1] Raised in a rural, agrarian environment dependent on enslaved labor, young Hardee grew up on the plantation, which provided the economic foundation for his family's status.[6] This upbringing instilled early exposure to Southern societal norms and agricultural management, preparing him for a path toward military education by age 18.[3]West Point Attendance and Graduation

Hardee entered the United States Military Academy at West Point on July 1, 1834, beginning a standard four-year cadet program focused on military discipline, engineering, and tactics.[8][9] He graduated on July 1, 1838, placing 26th in a class of 45 cadets, reflecting a middling academic performance amid rigorous coursework in mathematics, ordnance, and infantry drill.[3][9][10] No notable disciplinary incidents or exceptional achievements are recorded from his cadet years, consistent with the era's emphasis on perseverance over individual distinction for most graduates.[8]Antebellum Military Career

Service in the Seminole and Mexican-American Wars

Hardee received his commission as a second lieutenant in the 2nd Regiment of Dragoons on July 1, 1838, shortly after graduating from the United States Military Academy, and was promptly assigned to active duty in the Second Seminole War in Florida.[11] In this capacity, he engaged in mounted operations against Seminole insurgents amid the protracted guerrilla conflict, which had begun in 1835 and involved U.S. forces pursuing Native American bands through swamps and dense terrain.[12] His service in the dragoons emphasized reconnaissance, rapid pursuit, and skirmishing, though specific engagements involving Hardee remain sparsely documented in primary accounts; the regiment's efforts focused on disrupting Seminole supply lines and capturing leaders like Osceola, who had already been imprisoned by 1838.[1] Hardee's Seminole tour ended prematurely in 1840 due to a severe illness that required his evacuation from the malarial Florida environment, leading to convalescence and subsequent studies at the French École de Cavalerie in Saumur from 1840 to 1842.[1] Upon returning to the United States, he resumed dragoon duties along the frontier, advancing to first lieutenant in 1840 and captain in 1844, with assignments including frontier patrols in Texas that honed his experience in irregular warfare against Comanche and other tribes.[12] These early postings exposed him to the challenges of mounted infantry tactics in varied terrains, influencing his later doctrinal writings. With the outbreak of the Mexican-American War in 1846, Hardee joined General Zachary Taylor's Army of Occupation in Texas as a captain, participating in the initial cross-border advance following the Thornton Affair on April 25, 1846.[7] He saw action in northern Mexico, including a skirmish at Medellín on March 25, 1847, south of Veracruz, for which he earned a brevet promotion to major on April 9, 1847, cited for "gallant and meritorious conduct."[7] [13] During Winfield Scott's Veracruz campaign and subsequent push toward Mexico City, Hardee received a second brevet to lieutenant colonel for distinguished service, though he was briefly captured by Mexican forces—possibly at Carricitos Ranch early in the conflict—and exchanged to rejoin operations.[14] [3] His wartime performance, marked by effective dragoon maneuvers in combined arms assaults, established his reputation as a capable field officer capable of adapting U.S. cavalry to offensive thrusts against fortified positions.[14]Commandant Role at West Point

Hardee was appointed commandant of cadets at the United States Military Academy by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis on July 22, 1856, following the death of his first wife in 1853 and his prior service on frontier duty.[8][3] In this capacity, he held a local rank of lieutenant colonel starting June 12, 1858, and oversaw the daily discipline, drill, and instruction of approximately 300-400 cadets, enforcing regulations on conduct, hygiene, and academic performance while coordinating their practical military exercises.[8][9] Concurrently, Hardee served as the primary instructor of infantry tactics from July 22, 1856, and additionally as instructor of artillery and cavalry tactics from August 6, 1856, through the end of his tenure on September 8, 1860, emphasizing formations, maneuvers, and the application of rifled muskets in line and skirmish tactics drawn from European models he had studied during captivity in Mexico.[8] His approach prioritized rigorous enforcement of order, with cadets under his command participating in frequent parades, guard duties, and field training to instill habits of precision and obedience essential for future officers.[3] Hardee earned a reputation as a firm disciplinarian, balancing strict accountability—such as demerits for infractions—with mentorship that prepared cadets for combat leadership.[3] During his service, Hardee mentored and trained numerous cadets who later achieved distinction in the Civil War on both Union and Confederate sides, including figures like future generals who credited his emphasis on tactical proficiency for their battlefield readiness.[3][6] On June 28, 1860, he received a permanent promotion to lieutenant colonel in the 1st Cavalry, reflecting recognition of his administrative and instructional effectiveness at the academy.[8] His tenure concluded amid rising sectional tensions, after which he returned to regimental duties before resigning his U.S. commission.[8]Authorship and Impact of Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics

William J. Hardee, then a brevet major in the U.S. Army, authored Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics in 1855 at the direction of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who appointed him to a board tasked with developing updated infantry drill manuals suited to the rifled muskets increasingly replacing smoothbore muskets in U.S. service.[15] The manual drew heavily from French light infantry doctrines, reflecting Hardee's prior studies at the French Army's Saumur Cavalry School and his exposure to European tactical innovations emphasizing speed, skirmishing, and dispersed formations for rifle-armed troops.[16] It comprised detailed instructions across multiple volumes, covering the "school of the soldier" (individual drill), company evolutions, battalion maneuvers, and light infantry operations, including formations for skirmish lines and assaults that prioritized volley fire and bayonet charges in linear or columnar arrangements.[17] Adopted as the official U.S. Army infantry manual in 1855, Hardee's Tactics standardized training for regular and volunteer forces, supplanting earlier smoothbore-era manuals like Silas Casey's and influencing pre-war drill at institutions such as West Point, where Hardee served as commandant.[15] During the American Civil War (1861–1865), it became the foundational text for both Union and Confederate armies, with Union regulars relying on the 1855 edition and Confederates printing numerous imprints; its emphasis on disciplined close-order drill and light infantry roles shaped early engagements, though the rifle-musket's extended range (up to 500 yards effective) often compelled deviations toward cover, entrenchments, and skirmisher-heavy tactics not fully anticipated in the manual.[18] Historians note that while Hardee's formations contributed to high casualties in open-field battles like Gettysburg (1863), its structured approach to volley and maneuver fire provided a baseline for adapting to rifled weaponry, as evidenced in analyses of battles such as Second Bull Run (1862), where infantry executed Hardee-derived assaults but suffered from exposed linear advances.[19] Following his resignation from the U.S. Army in 1861 to join the Confederacy, Hardee revised the manual as Rifle and Infantry Tactics, Revised and Improved (also known as Hardee's Revised Tactics), incorporating adaptations for the Confederacy's mixed armament, including provisions for three-band Enfield rifle-muskets and older muskets, with updated manuals of arms and simplified evolutions for rapid training of raw recruits.[20] Confederate editions, printed in cities like Memphis and Richmond, proliferated due to the South's resource constraints, ensuring widespread dissemination; this revision maintained core principles but emphasized flexibility for irregular warfare, influencing Southern commanders like Braxton Bragg in the Western Theater.[21] The manual's enduring impact lay in its role as a tactical lingua franca across armies, fostering interoperability in captured units and post-war reminiscences, though critics later argued its Napoleonic roots inadequately addressed industrialized firepower, prompting doctrinal shifts toward defensive postures by war's end.[22]Confederate Military Service

Resignation from U.S. Army and Initial Confederate Commands

William J. Hardee resigned his commission as a major in the United States Army on January 31, 1861, shortly after Georgia's secession ordinance on January 19, 1861.[8][1] This decision reflected the prevailing sentiment among Southern officers, who viewed allegiance to their states as paramount in the wake of secession, prompting over 300 U.S. Army officers to follow suit by mid-1861.[14] Hardee promptly offered his services to the Confederate States, initially receiving a colonel's commission in the Confederate army.[1] In early 1861, he was dispatched to Arkansas—the first Confederate general officer assigned there—to organize and train state troops for federal service.[3] Assuming command of the Upper District of Arkansas, Hardee mustered several regiments, including the 5th through 8th Arkansas Infantry, applying principles from his Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics to instill discipline in inexperienced volunteers.[23] On June 17, 1861, Hardee was promoted to brigadier general, enabling him to expand his supervisory role over training camps and fortifications in northeastern Arkansas.[6] His efforts focused on transforming disorganized militia into cohesive units capable of field operations, a critical step given Arkansas's strategic position bordering Union-held Missouri. By October 7, 1861, further promotion to major general solidified his authority, positioning him for larger commands in the Western Theater as Confederate forces mobilized against federal advances.[14][3]Key Campaigns in the Western Theater

In March 1862, Hardee was transferred from command in northeastern Arkansas to join General Albert Sidney Johnston's Army of Mississippi, where he took charge of the Third Corps with approximately 7,500 men.[24] At the Battle of Shiloh on April 6–7, 1862, Hardee's corps led the initial Confederate assault, capturing the Peach Orchard and advancing against Union divisions under William Tecumseh Sherman and Benjamin M. Prentiss, though the attack stalled amid heavy casualties and counterattacks.[25] Hardee sustained a minor wound to his arm during the fighting, which saw Confederate forces numbering about 44,000 clash with 48,500 Union troops, resulting in over 23,000 total casualties and a tactical Union victory as Johnston's army withdrew.[25] Following Shiloh, under P.G.T. Beauregard, Hardee's corps participated in the defense of Corinth, Mississippi, during the Union siege from April to May 1862, culminating in the Confederate evacuation on May 30 after destroying rail facilities and supplies to deny them to pursuing forces under Henry Halleck.[26] During Braxton Bragg's Kentucky invasion in the fall of 1862, Hardee commanded the Army of Mississippi's right wing, comprising two divisions, as it advanced northward to counter Union advances.[24] At the Battle of Perryville on October 8, 1862, Hardee's forces engaged Union elements under Philip Sheridan and James S. Jackson near Doctor's Creek, inflicting heavy losses including the death of Jackson, though Bragg ordered a withdrawal the next day due to water shortages and reinforcements arriving for Don Carlos Buell, with Confederate casualties around 3,200 against 4,200 Union.[27] Hardee was promoted to lieutenant general on October 10, 1862, recognizing his performance.[14] In the subsequent Battle of Stones River (Murfreesboro) from December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863, Hardee's corps spearheaded the Confederate attack on the Union left flank, seizing Round Forest after intense combat and contributing to initial gains against William S. Rosecrans's 42,000 troops, but coordination failures with Leonidas Polk's wing and Union reinforcements led to a Confederate retreat on January 3, with 10,000 Confederate casualties from an effective strength of 35,000 compared to 13,000 Union losses.[28] [14] Amid growing tensions with Bragg, Hardee participated in the Tullahoma Campaign from June 23 to July 7, 1863, where his corps maneuvered defensively as Rosecrans outflanked Bragg's 46,000-man army through feints and rapid marches, forcing the abandonment of key Tennessee positions without major battles and inflicting minimal Confederate casualties of about 100 against 600 Union.[24] At Chickamauga on September 19–20, 1863, commanding the left wing of Bragg's Army of Tennessee, Hardee's corps assaulted Union positions along Brotherton and Viniard fields, breaking through on the second day to secure a rare Confederate victory that inflicted 16,000 Union casualties against 18,000 Confederate, though pursuit faltered.[14] During the Chattanooga Campaign, Hardee's corps defended the northern sector of Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863, against George H. Thomas's assault, but after Union breakthroughs elsewhere, he oversaw an orderly retreat across the Tennessee River, contributing to the Army of Tennessee's 6,700 casualties in the failed offensive.[24]Tactical Innovations and Battlefield Performance

Hardee's Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics, originally published in 1855 and revised for Confederate use during the war, represented a key adaptation of European light infantry doctrines to rifled muskets, emphasizing extended skirmish lines, company columns for rapid deployment, and simplified regimental maneuvers to exploit the weapon's increased effective range of up to 300 yards.[19][29] These innovations accelerated drill paces and facilitated flexible formations in broken terrain, diverging from rigid Napoleonic lines by incorporating more dispersed, rifle-suited skirmishing that both Union and Confederate forces adopted as a prewar standard.[22] However, wartime realities—such as inexperienced troops and dense underbrush—often compelled deviations, with Hardee's emphasis on thorough training proving more influential in corps-level preparation than strict adherence to manual formations amid the conflict's evolution toward entrenched firepower.[19] In the Battle of Shiloh on April 6–7, 1862, Hardee's III Corps of approximately 6,700 men spearheaded the Confederate assault on the Union left flank along Ridge Road, employing successive two-rank lines and skirmishers per his manual to overrun camps like Peabody's by 9:00 a.m., capturing artillery and achieving initial overlaps on Union positions.[25][14] Momentum faltered after pauses for reorganization, allowing Union forces under Grant to consolidate at sites like the Hornet's Nest, where Hardee's frontal advances incurred heavy losses without decisive penetration; a counterattack at Jones Field by 2:00 p.m. was repulsed.[25] On April 7, his corps held against Union counteroffensives from Nelson and Crittenden's divisions for six hours near Sarah Bell Field and the Sunken Road, committing ad hoc brigades reactively, but collapsed by 2:30 p.m. amid ammunition shortages and fresh Union arrivals numbering 18,000, contributing to the Confederate retreat to Corinth with Hardee sustaining an arm wound.[25][14] This performance highlighted Hardee's tactical proficiency in offensive starts but exposed limitations in sustaining drives against resilient defenses, exacerbated by subordinate inexperience and terrain.[25] Subsequent engagements in the Western Theater underscored Hardee's reputation as a methodical corps commander, earning him the moniker "Old Reliable" for disciplined execution under Braxton Bragg and Joseph E. Johnston.[14] At Stones River (December 31, 1862–January 2, 1863), his corps executed a surprise dawn attack on Union right under Rosecrans, shattering lines and advancing significantly before stalling in a bloody stalemate with 23,000 total casualties.[1][14] In the Atlanta Campaign (May–September 1864), commanding under Johnston and then Hood after July 17, Hardee's corps conducted delaying actions and fortified withdrawals, such as at Jonesborough (August 31–September 1), but suffered repeated repulses amid Hood's aggressive orders, prompting Hardee's transfer due to strategic disputes.[1][14] At Savannah in December 1864, facing Sherman's 62,000 with 9,000 defenders, Hardee orchestrated a skillful evacuation on December 20–21 via an improvised pontoon bridge across the Savannah River, preserving his force without battle while abandoning the city, demonstrating adaptive defensive tactics over futile holds.[30] Overall, Hardee's battlefield record reflected competent tactical handling of infantry assaults and retreats—effective in localized successes like Chickamauga (September 19–20, 1863)—but constrained by superior command decisions and logistical strains, with his prewar doctrines providing a foundational yet increasingly outdated framework against industrialized warfare's demands.[14][1]| Battle | Date | Hardee's Role and Key Actions | Outcome for His Command |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shiloh | April 6–7, 1862 | Led initial corps assault; successive lines overran camps but stalled at fortifications | Partial gains; retreat after heavy losses; personal wound |

| Stones River | December 31, 1862–January 2, 1863 | Surprise attack shattered Union right | Stalemate; high casualties but tactical success in assault |

| Atlanta Campaign (e.g., Jonesborough) | May–September 1864 | Corps delays and defenses under Hood | Withdrawals; defeats amid command friction |

| Savannah | December 1864 | Defensive hold and pontoon evacuation | City lost but army preserved |