Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Atlanta campaign

View on Wikipedia

| Atlanta Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

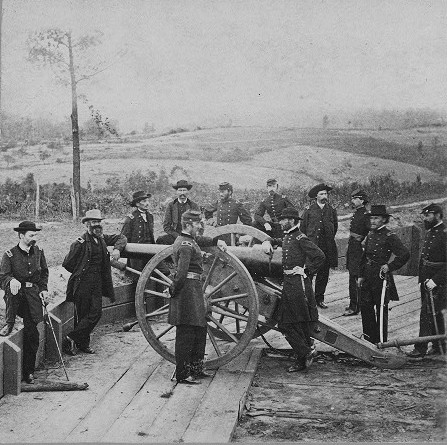

Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman and his staff in the trenches outside of Atlanta | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of Tennessee[2] | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 112,819[3] | Beginning – 60,000 Infantry, 11,000 cavalry, 7,000 Artillery[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

31,687; (4,423 killed, 22,822 wounded, 4,442 missing/captured) |

34,979; (3,044 killed, 18,952 wounded, 12,983 missing/captured) | ||||||

| |||||||

The Atlanta campaign was a series of battles fought in the Western Theater of the American Civil War throughout northwest Georgia and the area around Atlanta during the summer of 1864. Union Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman invaded Georgia from the vicinity of Chattanooga, Tennessee, beginning in May 1864, opposed by the Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston.

Johnston's Army of Tennessee withdrew toward Atlanta in the face of successive flanking maneuvers by Sherman's group of armies. In July, the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, replaced Johnston with the more aggressive General John Bell Hood, who began challenging the Union Army in a series of costly frontal assaults. Hood's army was eventually besieged in Atlanta and the city fell on September 2, setting the stage for Sherman's March to the Sea and hastening the end of the war.

Background

[edit]Military situation

[edit]The Atlanta campaign followed the Union victory in the Battles for Chattanooga in November 1863; Chattanooga was known as the "Gateway to the South", and its capture opened that gateway. After Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to general-in-chief of all Union armies, he left his favorite subordinate from his time in command of the Western Theater, William T. Sherman, in charge of the Western armies. Grant's strategy was to apply pressure against the Confederacy in several coordinated offensives. While he, George G. Meade, Benjamin Butler, Franz Sigel, George Crook, and William W. Averell advanced in Virginia against Robert E. Lee, and Nathaniel Banks attempted to capture Mobile, Alabama, Sherman was assigned the mission of defeating Johnston's army, capturing Atlanta, and striking through Georgia and the Confederate heartland.

Opposing forces

[edit]Union

[edit]| Principal Union commanders |

|---|

|

At the start of the campaign, Sherman's Military Division of the Mississippi consisted of three armies:[5]

- Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson's Army of the Tennessee (Sherman's army under Grant in 1863), including the corps of Maj. Gen. John A. Logan (XV Corps), Maj. Gen. Grenville M. Dodge (XVI Corps), and Maj. Gen. Francis P. Blair Jr. (XVII Corps). When McPherson was killed at the Battle of Atlanta, Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard replaced him.

- Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield's Army of the Ohio, consisting of Schofield's XXIII Corps and a cavalry division commanded by Maj. Gen. George Stoneman.

- Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas's Army of the Cumberland, including the corps of Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard (IV Corps), Maj. Gen. John M. Palmer (XIV Corps), Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker (XX Corps), and Brig. Gen. Washington L. Elliott (Cavalry Corps). After Howard took army command, David S. Stanley took over IV Corps.

On paper at the beginning of the campaign, Sherman outnumbered Johnston 98,500 to 50,000,[5] but his ranks were initially depleted by many furloughed soldiers, and Johnston received 15,000 reinforcements from Alabama. However, by June, a steady stream of reinforcements brought Sherman's strength to 112,000.[6]

Confederate

[edit]| Principal Confederate commanders |

|---|

|

Opposing Sherman, the Army of Tennessee was commanded first by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, who was relieved of his command in mid-campaign and replaced by Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood. The four corps in the 50,000-man army were commanded by:[5]

- Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee (divisions of Maj. Gens. Benjamin F. Cheatham, Patrick R. Cleburne, William H. T. Walker, and William B. Bate).

- Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood (divisions of Maj. Gens. Thomas C. Hindman, Carter L. Stevenson, and Alexander P. Stewart).

- Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk (also called the Army of Mississippi, with the infantry divisions of Maj. Gen. William W. Loring, Samuel G. French, and Edward C. Walthall, and a cavalry division under Brig. Gen. William Hicks Jackson). When Polk was killed on June 14, Loring briefly took over as commander of the corps but was then replaced by Alexander P. Stewart on June 23.

- Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler (Cavalry corps, with the divisions of Maj. Gen. William T. Martin and Brig. Gens. John H. Kelly and William Y. C. Humes).

Johnston was a conservative general with a reputation for withdrawing his army before serious contact would result; this was certainly his pattern against George B. McClellan in the Peninsula Campaign of 1862. But in Georgia, he faced the much more aggressive Sherman. Johnston's army repeatedly took up strongly entrenched defensive positions in the campaign. Sherman prudently avoided suicidal frontal assaults against most of these positions, instead maneuvering in flanking marches around the defenses as he advanced from Chattanooga towards Atlanta. Whenever Sherman flanked the defensive lines (almost exclusively around Johnston's left flank), Johnston would retreat to another prepared position. Both armies took advantage of the railroads as supply lines, with Johnston shortening his supply lines as he drew closer to Atlanta, and Sherman lengthening his own.

Summary

[edit]| Date | Event |

|---|---|

May 1, 1864

|

Skirmish at Stone Church. |

May 2, 1864

|

Skirmish at Lee's Cross-Roads, near Tunnel Hill. |

| Skirmish near Ringgold Gap. | |

May 10, 1864

|

Skirmish at Catoosa Springs. |

| Skirmish at Red Clay. | |

| Skirmish at Chickamauga Creek. | |

May 4, 1864

|

Maj. Gen. Frank P. Blair Jr., assumes command of the Seventeenth Army Corps. |

| Skirmish on the Varnell's Station Road. | |

May 5, 1864

|

Skirmish near Tunnel Hill. |

May 6–7, 1864

|

Skirmishes at Tunnel Hill. |

May 7, 1864

|

Skirmish at Varnell's Station. |

| Skirmish near Nickajack Gap. | |

May 8–11, 1864

|

Demonstration against Rocky Face Ridge, with combats at Buzzard Roost or Mill Creek Gap, and Dug Gap. |

May 8–13, 1864

|

Demonstration against Resaca, with combats at Snake Creek Gap, Sugar Valley, and near Resaca. |

May 9–13, 1864

|

Demonstration against Dalton, with combats near Varnell's Station (9th and 12th) and at Dalton (13th). |

May 13, 1864

|

Skirmish at Tilton. |

May 14–15, 1864

|

Battle of Resaca. |

May 15, 1864

|

Skirmish at Armuchee Creek. |

| Skirmish near Rome. | |

May 16, 1864

|

Skirmish near Calhoun. |

| Action at Rome (or Parker's) Cross-Roads. | |

| Skirmish at Floyd's Spring. | |

May 17, 1864

|

Engagement at Adairsville. |

| Action at Rome. | |

| Affair at Madison Station, Ala. | |

May 18, 1864

|

Skirmish at Pine Log Creek. |

May 18–19, 1864

|

Combats near Kingston. |

| Combats near Cassville. | |

May 20, 1864

|

Skirmish at Etowah River, near Cartersville. |

May 23, 1864

|

Action at Stilesborough. |

May 24, 1864

|

Skirmishes at Cass Station and Cassville. Skirmish at Burnt Hickory (or Huntsville). |

| Skirmish near Dallas. | |

May 25 – June 5, 1864

|

Operations on the line of Pumpkin Vine Creek, with combats at New Hope Church, Pickett's Mills, and other points. |

May 26 – June 1, 1864

|

Combats at and about Dallas. |

May 27, 1864

|

Skirmish at Pond Springs, Ala. |

May 29, 1864

|

Action at Moulton, Ala. |

June 9, 1864

|

Skirmishes near Big Shanty and near Stilesborough. |

June 10, 1864

|

Skirmish at Calhoun. |

June 10 – July 3, 1864

|

Operations about Marietta, with combats at Pine Hill, Lost Mountain, Brush Mountain, Gilgal Church, Noonday Creek, McAfee's Cross-Roads, Kennesaw Mountain, Powder Springs, Cheney's Farm, Kolb's Farm, Olley's Creek, Nicka-jack Creek, Noyes' Creek, and other points. Popular general Leonidas Polk killed. |

June 24, 1864

|

Action at La Fayette. |

June 27, 1864

|

Battle of Kennesaw Mountain |

July 4, 1864

|

Skirmishes at Ruff's Mill, Neal Dow Station, and Rottenwood Creek. |

July 5–17, 1864

|

Operations on the line of the Chattahoochee River, with skirmishes at Howell's, Turner's, and Pace's Ferries, Isham's Ford, and other points. |

July 10–22, 1864

|

Rousseau's Opelika Raid raid from Decatur, Ala., to the West Point and Montgomery Railroad, with skirmishes near Coosa River (13th), near Greenpoint and at Ten Island Ford (14th), near Auburn, Ala and near Chehaw, Ala (18th). |

July 18, 1864

|

Skirmish at Buck Head. |

| General John B. Hood, C. S. Army, supersedes General Joseph E. Johnston in command of the Army of Tennessee.

Confederate Army Command Changed | |

July 19, 1864

|

Skirmishes on Peachtree Creek. |

July 20, 1864

|

Battle of Peachtree Creek. |

July 21, 1864

|

Engagement at Bald (or Leggett's) Hill. |

July 22, 1864

|

Battle of Atlanta. |

| Maj. Gen. John A. Logan, U.S. Army, succeeds Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson in command of the Army of the Tennessee. | |

July 22–24, 1864

|

Garrard's raid to Covington. |

July 23, 1864

|

Brig. Gen.Morgan L. Smith, U.S. Army, in temporary command of the Fifteenth Army Corps. |

July 23 – August 25, 1864

|

Operations about Atlanta, including Battle of Ezra Church (July 28), assault at Utoy Creek (August 6), and other combats. |

July 24, 1864

|

Skirmish near Cartersville. |

July 27, 1864

|

Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, U.S. Army, assumes command of the Army of the Tennessee. |

| Maj. Gen. John A. Logan, U.S. Army, resumes command of the Fifteenth Army Corps. | |

| Maj. Gen. David S. Stanley, U.S. Army, succeeds Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard in command of the Fourth Army Corps. | |

| Brig. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams, U.S. Army, succeeds Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker in temporary command of the Twentieth Army Corps. | |

July 27–31, 1864

|

McCook's raid on the Atlanta and West Point and Macon and Western Railroads, with skirmishes near Campbellton (28th), near Lovejoy's Station (29th), at Clear Creek (30th), and action at Brown's Mill near Newnan (30th). |

| Garrard's raid to South River, with skirmishes at Snapfinger Creek (27th), Flat Rock Bridge and Lithonia (28th). | |

July 27 – August 6, 1864

|

Stoneman's raid to Macon, with combats at Macon and Clinton (July 30), Hillsborough (July 30–31), Mulberry Creek and Jug Tavern (August 8). |

July 30, 1864

|

Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum, U.S. Army, assigned to the command of the Twentieth Army Corps. |

August 7, 1864

|

Brig. Gen. Richard W. Johnson, U.S. Army, succeeds Maj. Gen. John M. Palmer in temporary command of the Fourteenth Army Corps. |

August 9, 1864

|

Bvt. Maj. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis, U.S. Army, assigned to the command of the Fourteenth Army Corps. |

August 10 – September 9, 1864

|

Wheeler's raid to North Georgia and East Tennessee, with combats at Dalton (August 14–15) and other points. |

August 15, 1864

|

Skirmishes at Sandtown and Fairburn. |

August 18–22, 1864

|

Kilpatrick's raid from Sandtown to Lovejoy's Station, with combats at Camp Creek (18th), Red Oak (19th), Flint River (19th), Jonesborough (19th), and Lovejoy's Station (20th). |

August 22, 1864

|

Bvt. Maj. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis, U.S. Army, assumes command of the Fourteenth Army Corps. |

August 26 – September 1, 1864

|

Operations at the Chattahoochee railroad bridge and at Pace's and Turner's Ferries, with skirmishes. |

August 27, 1864

|

Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum, U.S. Army, assumes command of the Twentieth Army Corps. |

August 29, 1864

|

Skirmish near Red Oak. |

August 30, 1864

|

Skirmish near East Point. |

| Action at Flint River Bridge. | |

August 31, 1864

|

Skirmish near Rough and Ready Station. |

August 31 – September 1, 1864

|

Battle of Jonesborough. |

September 2, 1864

|

Union occupation of Atlanta. |

September 2–5, 1864

|

Actions at Lovejoy's Station. |

Battles

[edit]Sherman vs. Johnston

[edit]

Rocky Face Ridge (May 7–13, 1864)

[edit]Johnston had entrenched his army on the long, high mountain of Rocky Face Ridge and eastward across Crow Valley. Sherman had earlier decided to demonstrate against the strong Confederate position with the bulk of his force while he sent a smaller portion through Snake Creek Gap, to the right, to hit the Western & Atlantic Railroad at Resaca, Georgia. With sufficient men, the Union Army could cut off the Confederate lines of communication to the south and force Johnston to attack them or disperse his army traveling through the rough terrain to the east. The larger Union force engaged the enemy at Buzzard Roost (Mill Creek Gap) and at Dug Gap drawing away their attention. In the meantime, the third column, under McPherson, passed unnoticed through Snake Creek Gap and on May 9 advanced to the outskirts of Resaca, where it found a small Confederate force entrenched. Fearing defeat, McPherson pulled his column back to Snake Creek Gap, which Sherman's orders gave him authority to do. On May 10, Sherman decided to take most of his men and join McPherson to take Resaca. The next morning, as he discovered Sherman's army withdrawing from their positions in front of Rocky Face Ridge, Johnston retired south towards Resaca.[8] So began the first of a long series of flanking maneuvers by Sherman against Johnston; Sherman became so good at the tactic that his men boasted that Sherman "could flank the devil out of hell, if necessary." Johnston would be flanked out of every position he held until eventually relieved of command. The opportunity to destroy or disorganize the Confederates in the campaign's first battle, however, was missed.[9]

Resaca (May 13–15)

[edit]Union troops tested the Confederate lines around Resaca to pinpoint their whereabouts. Full scale fighting occurred on May 14, and the Union troops were generally repulsed except on Johnston's right flank, where Sherman did not fully exploit his advantage. On May 15, the battle continued with no advantage to either side until Sherman sent a force across the Oostanaula River at Lay's Ferry, towards Johnston's railroad supply line. Unable to halt this Union movement, Johnston was forced to retire.[10]

Adairsville (May 17)

[edit]Johnston's army retreated southward while Sherman pursued. Failing to find a good defensive position south of Calhoun, Johnston continued to Adairsville while the Confederate cavalry fought a skillful rearguard action. On May 17, Howard's IV Corps ran into entrenched infantry of Hardee's corps, while advancing about two miles (3.2 km) north of Adairsville. Three Union divisions prepared for battle, but Thomas halted them because of the approach of darkness. Sherman then concentrated his men in the Adairsville area to attack Johnston the next day. Johnston had originally expected to find a valley at Adairsville of suitable width to deploy his men and anchor his line with the flanks on hills, but the valley was too wide, so Johnston disengaged and withdrew.[11]

New Hope Church (May 25–26)

[edit]After Johnston retreated to Allatoona Pass from May 19 to 20, Sherman decided that attacking Johnston there would be too costly, so he determined to move around Johnston's left flank and steal a march toward Dallas. Johnston anticipated Sherman's move and met the Union forces at New Hope Church. Sherman mistakenly surmised that Johnston had a token force and ordered Hooker's XX Corps to attack. This corps was severely mauled. On May 26, both sides entrenched.[12]

Dallas (May 26 – June 1)

[edit]Sherman's army tested the Confederate line. On May 28, Hardee's corps probed the Union defensive line, held by Logan's XV Corps, to exploit any weakness or possible withdrawal. Fighting ensued at two different points, but the Confederates were repulsed, suffering high casualties. Sherman continued looking for a way around Johnston's line, and on June 1, his cavalry occupied Allatoona Pass, which had a railroad and would allow his men and supplies to reach him by train. Sherman abandoned his lines at Dallas on June 5 and moved toward the railhead at Allatoona Pass, forcing Johnston to follow soon afterward.[13]

Pickett's Mill (May 27)

[edit]After the Union defeat at New Hope Church, Sherman ordered Howard to attack Johnston's seemingly exposed right flank. The Confederates were ready for the attack, which did not unfold as planned because supporting troops never appeared. The Confederates repulsed the attack, causing high casualties.[14]

Operations around Marietta (June 9 – July 3)

[edit]When Sherman first found Johnston entrenched in the Marietta area on June 9, he began extending his lines beyond the Confederate lines, causing some Confederate withdrawal to new positions. On June 14, Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk was killed by an artillery shell while scouting enemy positions with Hardee and Johnston and was temporarily replaced by Maj. Gen. William W. Loring. On June 18–19, Johnston, fearing envelopment, moved his army to a new, previously selected position astride Kennesaw Mountain, an entrenched arc-shaped line to the west of Marietta, to protect his supply line, the Western & Atlantic Railroad. Sherman made some unsuccessful attacks on this position but eventually extended the line on his right and forced Johnston to withdraw from the Marietta area on July 2–3.[15]

Kolb's Farm (June 22)

[edit]Having encountered entrenched Confederates astride Kennesaw Mountain stretching southward, Sherman fixed them in front and extended his right wing to envelop their flank and menace the railroad. Johnston countered by moving Hood's corps from the left flank to the right on June 22. Arriving in his new position at Mt. Zion Church, Hood decided on his own to attack. Warned of Hood's intentions, Union generals John Schofield and Joseph Hooker entrenched. Union artillery and swampy terrain thwarted Hood's attack and forced him to withdraw with heavy casualties. Although he was the victor, Sherman's attempts at envelopment had momentarily failed.[16]

Kennesaw Mountain (June 27)

[edit]This battle was a notable exception to Sherman's policy in the campaign of avoiding frontal assaults and moving around the enemy's left flank. Sherman was sure that Johnston had stretched his line on Kennesaw Mountain too thin and decided on a frontal attack with some diversions on the flanks. On the morning of June 27, Sherman sent his troops forward after an artillery bombardment. At first, they made some headway overrunning Confederate pickets south of the Burnt Hickory Road, but attacking an enemy that was dug in was futile. The fighting ended by noon, and Sherman suffered heavy casualties, about 3,000, compared with 1,000 for the Confederates.[17] Johnston fell back toward Smyrna on July 3 and by July 4 to a defensive line along the west bank of the Chattahoochee River that became known as Johnston's River Line.

Pace's Ferry (July 5)

[edit]Johnston put the Chattahoochee River between his army and Sherman's. General Howard's IV corps advanced on Pace's Ferry on the river. The Confederate pontoon bridge there was defended by dismounted cavalry. They were driven away by BG Thomas J. Wood's division of IV Corps. The bridge, although damaged, was captured. Howard decided not to force a crossing against increased Confederate opposition. When federal pontoons arrived on July 8, Howard crossed the river and outflanked the Pace's Ferry defenders. This forced them to withdraw; and this permitted Sherman to cross the river, advancing closer to Atlanta. Johnston abandoned the River Line and retired south of Peachtree Creek, about three miles (4.8 km) north of Atlanta.

Sherman vs. Hood

[edit]Due to public pressure, Confederate President Jefferson Davis had become increasingly irate at Johnston giving ground. Finally, on July 17, Davis stripped Johnston of command and replaced him with John Bell Hood. Hood may have seemed a more able commander than Johnston, especially on the attack, as seen at Gettysburg, but the Army of Tennessee was short on men, talent, and luck. Sherman had been frustrated by Johnston's defensive tactics and was reportedly pleased with the change as the aggressive Hood was more willing to do open battle, thus giving Sherman opportunities to use his superior numbers and firepower to destroy Confederate forces.[18]

Peachtree Creek (July 20)

[edit]After crossing the Chattahoochee, Sherman split his army into three columns for the assault on Atlanta with Thomas' Army of the Cumberland, on the left, moving from the north. Schofield and McPherson had drawn away to the east, leaving Thomas on his own. Johnston decided to attack Thomas as he crossed the creek, but Confederate President Jefferson Davis relieved him of command and appointed Hood to take his place. Hood adopted Johnston's plan and attacked Thomas after his army crossed Peachtree Creek. The determined assault threatened to overrun the Union troops at various locations, but eventually the Union held, and the Confederates fell back. The advance of McPherson from the east side of Atlanta distracted Hood from his offensive and drew off Confederate troops that might have joined the attack on Thomas.[19]

Atlanta (July 22)

[edit]

Hood was determined to attack McPherson's Army of the Tennessee. He withdrew his main army at night from Atlanta's outer line to the inner line, enticing Sherman to follow. In the meantime, he sent William J. Hardee with his corps on a fifteen-mile (24 km) march to hit the unprotected Union left and rear, east of the city. Wheeler's cavalry was to operate farther out on Sherman's supply line, and Cheatham's corps was to attack the Union front. Hood, however, miscalculated the time necessary to make the march, and Hardee was unable to attack until afternoon. Although Hood had outmaneuvered Sherman for the time being, McPherson was concerned about his left flank and sent his reserves—Dodge's XVI Corps—to that location. Two of Hood's divisions ran into this reserve force and were repulsed. The Confederate attack stalled on the Union rear but began to roll up the left flank. Around the same time, a Confederate soldier shot and killed McPherson when he rode out to observe the fighting. Determined attacks continued, but the Union forces held. About 4 p.m., Cheatham's corps broke through the Union front, but massed artillery near Sherman's headquarters halted the Confederate assault. Logan's XV Corps then led a counterattack that restored the Union line. The Union troops held, and Hood suffered high casualties.[20]

Despite being called the Battle of Atlanta, the city itself would not fall until September.

Ezra Church (July 28)

[edit]Sherman's forces had previously approached Atlanta from the east and north and had not been able to break through, so Sherman decided to attack from the west. He ordered Howard's Army of the Tennessee to move from the left wing to the right and cut Hood's last railroad supply line between East Point and Atlanta. Hood foresaw such a maneuver and sent the two corps of Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee and Lt. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart to intercept and destroy the Union force at Ezra Church. Howard had anticipated such a thrust, entrenched one of his corps in the Confederates' path, and repulsed the determined attack, inflicting numerous casualties. Howard, however, failed to cut the railroad. Concurrent attempts by two columns of Union cavalry to cut the railroads south of Atlanta ended in failure, with one division under Maj. Gen. Edward M. McCook completely smashed at the Battle of Brown's Mill and the other force also repulsed and its commander, Maj. Gen. George Stoneman, taken prisoner.[21]

Utoy Creek (August 5–7)

[edit]After failing to envelop Hood's left flank at Ezra Church, Sherman still wanted to extend his right flank to hit the railroad between East Point and Atlanta. He transferred Schofield's Army of the Ohio from his left to his right flank and sent him to the north bank of Utoy Creek. Although Schofield's troops were at Utoy Creek on August 2, they, along with the XIV Corps, Army of the Cumberland, did not cross until August 4. Schofield's force began its movement to exploit this situation on the morning of August 5, which was initially successful. Schofield then had to regroup his forces, which took the rest of the day. The delay allowed the Confederates to strengthen their defenses with abatis, which slowed the Union attack when it restarted on the morning of August 6. The Federals were repulsed with heavy losses and failed in an attempt to break the railroad. On August 7, the Union troops moved toward the Confederate main line and entrenched. They remained there until late August.[22]

Dalton (August 14–15)

[edit]Wheeler and his cavalry raided into North Georgia to destroy railroad tracks and supplies. They approached Dalton in the late afternoon of August 14 and demanded the surrender of the garrison. The Union commander refused to surrender and fighting ensued. Greatly outnumbered, the Union garrison retired to fortifications on a hill outside the town where they successfully held out, although the attack continued until after midnight. Around 5 a.m. on August 15, Wheeler retired and became engaged with relieving infantry and cavalry under Maj. Gen. James B. Steedman's command. Eventually, Wheeler withdrew.[23]

Lovejoy's Station (August 20)

[edit]While Wheeler was absent raiding Union supply lines from North Georgia to East Tennessee, Sherman sent cavalry Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick to raid Confederate supply lines. Leaving on August 18, Kilpatrick hit the Atlanta & West Point Railroad that evening, tearing up a small area of tracks. Next, he headed for Lovejoy's Station on the Macon & Western Railroad. In transit, on August 19, Kilpatrick's men hit the Jonesborough supply depot on the Macon & Western Railroad, burning great amounts of supplies. On August 20, they reached Lovejoy's Station and began their destruction. Confederate infantry (Patrick Cleburne's Division) appeared and the raiders were forced to fight into the night, finally fleeing to prevent encirclement. Although Kilpatrick had destroyed supplies and track at Lovejoy's Station, the railroad line was back in operation in two days.[24]

Jonesborough (August 31 – September 1)

[edit]

In late August, Sherman determined that if he could cut Hood's railroad supply lines, the Confederates would have to evacuate Atlanta. Sherman had successfully cut Hood's supply lines in the past by sending out detachments of cavalry, but the Confederates quickly repaired the damage. He therefore decided to move six of his seven infantry corps against the supply lines. The army began pulling out of its positions on August 25 to hit the Macon & Western Railroad between Rough and Ready and Jonesborough. To counter the move, Hood sent Hardee with two corps to halt and possibly rout the Union troops, not realizing Sherman's army was there in force. On August 31, Hardee attacked two Union corps west of Jonesborough but was easily repulsed. Fearing an attack on Atlanta, Hood withdrew one corps from Hardee's force that night. The next day, a Union corps broke through Hardee's line, and his troops retreated to Lovejoy's Station. Sherman had cut Hood's supply line but he had failed to destroy Hardee's command.[25]

Fall of Atlanta (September 2)

[edit]On the night of September 1, Hood evacuated Atlanta and ordered that the 81 rail cars filled with ammunition and other military supplies be destroyed. The resulting fire and explosions were heard for miles.[N 1] Union troops under the command of Gen. Henry W. Slocum occupied Atlanta on September 2.[26]

On September 4, General Sherman issued Special Field Order #64. General Sherman announced to his troops that "The army having accomplished its undertaking in the complete reduction and occupation of Atlanta will occupy the place and the country near it until a new campaign is planned in concert with the other grand armies of the United States."[27]

Aftermath

[edit]

Sherman was victorious, and Hood established a reputation as the most recklessly aggressive general in the Confederate Army. Casualties for the campaign were roughly equal in absolute numbers: 31,687 Union (4,423 killed, 22,822 wounded, 4,442 missing/captured) and 34,979 Confederate (3,044 killed, 18,952 wounded, 12,983 missing/captured). But this represented a much higher Confederate proportional loss. Hood's army left the area with approximately 30,000 men, whereas Sherman retained 81,000.[28][29] Sherman's victory was qualified because it did not fulfill the original mission of the campaign—destroy the Army of Tennessee—and Sherman has been criticized for allowing his opponent to escape. However, the capture of Atlanta made an enormous contribution to Union morale and was an important factor in the re-election of President Abraham Lincoln.

Sherman realized that garrisoning Atlanta long-term would be a waste of troops, and that eventually the city would need to be abandoned.[30] But first the army needed to be replenished, and so Sherman occupied Atlanta for the time being. Though the city was already mostly empty, about 1,600 civilians remained (compared to about 10,000 before the war[31]) and Sherman felt their presence would be an obstacle. So, on September 14 Sherman issued Special Field Orders No. 67, which demanded the evacuation of the civilian population.[30][32]

Hood, though he had been unable to hold Atlanta, now planned a counter-action. But the details were divulged in a speech given by Confederate President Davis, which provided Sherman a clear view of Hood's strategy. Sherman left Atlanta garrisoned with only a single Corps, and took the rest of the army to chase down Hood in the Franklin–Nashville campaign. Despite the divulging of Hood's plans, Hood was able to seize the initiative, briefly drawing Sherman north from Atlanta. The chase lasted through November, before Sherman returned the army to Atlanta to prepare for the March to the Sea. Despite Hood and Sherman's armies being the main forces in the western theater, they would not meet again, and Hood's army would be effectively destroyed by George Henry Thomas instead.[33] Sherman's Army returned to Atlanta on November 12, spending just a few days to destroy anything of military value, including the railroads. Sherman's move was to be an evolution in warfare: without railroads for supply, the Army would have to live off the land. The Army withdrew from Atlanta on November 15, and so began Sherman's March to the Sea.[34]

Additional battle maps

[edit]Gallery: the Atlanta Campaign from the Atlas to Accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.

-

Map 1:

Sherman's advance: Tennessee, Georgia and Carolinas (1863–65). -

Map 2:

Atlanta Campaign: First epoch. -

Map 3:

Atlanta Campaign: Second epoch. -

Map 3:

Atlanta Campaign: Third epoch. -

Maps 4-5:

Atlanta Campaign: Fourth and Fifth epoch. -

Map 6:

Atlanta Campaign: Siege of Atlanta.

Gallery: Additional maps.

-

Map 1:

The Atlanta Campaign from Dalton to Kennesaw Mountain (May 7 – July 2, 1864). -

Map 2:

Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, June 27, 1864. -

Map 3:

A sketch of the Battle of Peachtree Creek, July 20, 1864. -

Map 3:

A sketch of the Battle of Atlanta, July 22, 1864. -

Maps 4-5:

A sketch of the Battle of Ezra Church, July 28, 1864.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Notes

- ^ Destruction of the Ordnance train and the Rolling Mill were dramatized in the 1939 film Gone with the Wind. Eyewitness accounts do not indicate that the fire spread beyond the rail yard.

Citations

- ^ Further information: Official Records, Series I, Volume XXXVIII, Part 1, pp. 89–114

- ^ Further information: Official Records, Series I, Volume XXXVIII, Part 3, pp. 638–675

- ^ Effective strength of the army under Maj. Gen. W. T. Sherman, during the campaign against Atlanta, Ga., 1864: Official Records, Series I, Volume XXXVIII, Part 1, pp. 115–117

- ^ Strength of the confederate forces: Official Records, Series I, Volume XXXVIII, Part 3, pp. 675–683

- ^ a b c Eicher, p. 696

- ^ McKay, p. 129.

- ^ OR Series 1, Volume 38 (Part I), pp. 52–54

- ^ NPS, Rocky Face Ridge Archived December 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Barrett 1956, p. 18.

- ^ NPS, Resaca Archived April 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NPS, Adairsville Archived December 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NPS, New Hope Church Archived January 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NPS, Dallas Archived August 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NPS, Pickett's Mill Archived September 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NPS, Marietta

- ^ NPS, Kolb's Farm Archived January 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Battle Summary: Kennesaw Mountain, GA". The American Battlefield Protection Program. National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008.

- ^ Barrett 1956, p. 19.

- ^ NPS, Peachtree Creek Archived January 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NPS, Atlanta Archived October 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NPS, Ezra Church Archived January 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NPS, Utoy Creek

- ^ NPS, Dalton II

- ^ NPS, Lovejoy's Station Archived October 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [1] NPS, Jonesborough

- ^ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, pp 433–634

- ^ [2] O.R. Series 1 – Volume 38 (Part V) p 801

- ^ McKay, p. 146

- ^ Foote, p. 529.

- ^ a b Barrett 1956, p. 20.

- ^ "1860 US Census: Atlanta" (PDF).

- ^ Garrett 1954, pp. 640–643.

- ^ Barrett 1956, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Barrett 1956, pp. 23–24.

References

[edit]- Barrett, John Gilchrist (1956). Sherman's march through the Carolinas (1st ed.). Chapel Hill. ISBN 978-1-4696-1112-9. OCLC 864900203.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bonds, Russell S. War Like the Thunderbolt: The Battle and Burning of Atlanta. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2009. ISBN 978-1-59416-100-1.

- Castel, Albert. Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992. ISBN 978-0-7006-0748-8.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of The Civil War. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1962. OCLC 19943283. LCCN 62-18682. The same with minor changes as Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars, volume 1. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 3, Red River to Appomattox. New York: Random House, 1974. ISBN 0-394-74913-8.

- Garrett, Franklin M. (1954). Atlanta and Environs, A Chronicle of its People and Events. Lewis Historical Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0820309132.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- McDonough, James Lee, and James Pickett Jones. War so Terrible: Sherman and Atlanta. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1987, ISBN 0-393-02497-0.

- McKay, John E. "Atlanta Campaign." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Welcher, Frank J. The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations. Vol. 2, The Western Theater. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-253-36454-X.

- National Park Service battle descriptions

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Park Service.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Park Service.

Memoirs and primary sources

[edit]- Sherman, William T., Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman, 2nd ed., D. Appleton & Co., 1913 (1889). Reprinted by the Library of America, 1990, ISBN 978-0-940450-65-3.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

Further reading

[edit]- Bailey, Anne J. The Chessboard of War: Sherman and Hood in the Atlanta Campaign of 1864. (University of Nebraska Press, 2000). ISBN 978-0-8032-1273-2.

- Davis, Stephen. A Long and Bloody Task: The Atlanta Campaign from Dalton through Kennesaw Mountain to the Chattahoochee River, May 5 – July 18, 1864. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2016. ISBN 978-1-61121-317-1.

- Davis, Stephen. All the Fighting They Want: The Atlanta Campaign from Peachtree Creek to the City's Surrender, July 18 – September 2, 1864. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2017. ISBN 978-1-61121-319-5.

- Evans, David. Sherman's Horsemen: Union Cavalry Operations in the Atlanta Campaign. (Indiana University Press, 1996). ISBN 0-253-32963-9.

- Hess, Earl J. Kennesaw Mountain: Sherman, Johnston and the Atlanta Campaign. (University of North Carolina Press, 2013). ISBN 978-1-4696-0211-0.

- Hood, Stephen M. John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2013. ISBN 978-1-61121-140-5.

- Jenkins Sr., Robert D. To the Gates of Atlanta: From Kennesaw Mountain to Peach Tree Creek, July 1–19, 1864 (Mercer University Press, 2015) xxiv, 378 pp.

- Jenkins Sr., Robert D. The Cassville Affairs: Johnson, Hood, and the Failed Confederate Strategy in The Atlanta Campaign, 19 May 1864. (Mercer University Press, 2024)

- Luvaas, Jay, and Harold W. Nelson, eds. Guide to the Atlanta Campaign: Rocky Face Ridge to Kennesaw Mountain. (University Press of Kansas, 2008). ISBN 978-0-7006-1570-4.

- Savas, Theodore P., and David A. Woodbury, eds. The Campaign for Atlanta & Sherman's March to the Sea: Essays on the American Civil War in Georgia, 1864. 2 vols. Campbell, CA: Savas Woodbury, 1994. ISBN 978-1-882810-26-0.

External links

[edit]- West Point Atlas Atlanta Campaign maps, May 4 – July 8

- West Point Atlas Atlanta Campaign maps, July 20 – September 3

- Operation Reports – Series 1, Volume XXXVIII – part 1 – Summary of the Principal Events, pp 52–54

- Animated History of the Atlanta Campaign

- The Civil War in Georgia as told by its historic markers – Engagement at Bald (or Leggett's) Hill July 21, 1863

- Who Burned Atlanta?

- Atlanta as Left by Our Troops

- Fort X

Atlanta campaign

View on GrokipediaStrategic and Political Background

Objectives in the Western Theater

In the Western Theater of the American Civil War, Union objectives centered on capturing Atlanta, Georgia, recognized as a critical rail junction linking Confederate territories east of the Mississippi River. Atlanta served as the intersection of four major railroads—the Western and Atlantic from Chattanooga, the Georgia Railroad from Augusta, the Macon and Western from Macon, and the Atlanta and West Point to the southwest—facilitating the movement of troops, supplies, and raw materials essential to sustaining Confederate operations across Virginia, Tennessee, and the Deep South.[4] Control of this chokepoint would sever key logistical arteries, compelling the Confederacy to divert scarce resources for repairs and alternative routing, thereby weakening its capacity to reinforce eastern armies and prolong the war.[5] Following Ulysses S. Grant's assumption of command over all Union armies in March 1864, he directed a coordinated spring offensive to dismantle Confederate resistance, with William T. Sherman's Army Group in the West tasked with advancing from Chattanooga to destroy Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee or, failing that, seize Atlanta to undermine the South's war economy. In a letter dated April 4, 1864, Grant instructed Sherman to "break up [Johnston's] army... and do the enemy all the harm you can," emphasizing the destruction of military infrastructure alongside territorial gains.[6] This directive aligned with Grant's broader strategy of simultaneous pressures to prevent Confederate reinforcements, positioning Atlanta's capture as a means to erode the enemy's industrial base and supply throughput, which by 1863 supported contracts for 175,000 shirts, 130,000 jackets, and 130,000 pairs of shoes from Atlanta's depots alone.[7] From a logistical standpoint, Atlanta's pre-campaign role amplified its strategic value: as a primary distribution hub, it channeled foodstuffs, munitions, and manufactured goods southward, with railroads enabling rapid redistribution despite deteriorating Confederate infrastructure, where train speeds had fallen to 10 miles per hour by 1863 due to maintenance shortages. Union seizure would force resource reallocations, straining an agrarian economy already reliant on vulnerable rail networks for wartime sustainment, thus causally linking territorial control to diminished Confederate operational endurance in multiple theaters.[8][9]Grant's Coordinated offensives and Political Stakes

In March 1864, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant assumed command of all Union armies and formulated a strategy of simultaneous, multi-theater offensives designed to overwhelm Confederate defenses by engaging their forces across a broad front, thereby preventing the rapid transfer of reinforcements between threatened sectors via rail networks.[10] This approach marked a departure from prior independent operations, coordinating advances to exploit the Union's advantages in manpower and logistics while fixing Confederate armies in place.[11] The principal thrusts included the Overland Campaign in Virginia, where the Army of the Potomac—numbering approximately 118,000 infantry and artillery under Major General George G. Meade—crossed the Rapidan River on May 4; Sherman's combined force of about 98,000 men from the Armies of the Cumberland, Tennessee, and Ohio advancing from Chattanooga starting May 7; Major General Benjamin F. Butler's 30,000 troops landing at Bermuda Hundred on May 5 to threaten Richmond; and Brigadier General Franz Sigel's 6,800-man column moving up the Shenandoah Valley on May 2.[12][1] Grant's doctrine emphasized relentless pressure through attrition, accepting higher Union casualties in exchange for inflicting irreplaceable losses on the Confederacy, whose limited population and resources could not sustain prolonged engagements without collapsing.[13] By May 1864, Confederate armies faced acute manpower shortages, with Lee's Army of Northern Virginia totaling around 64,000 effectives and Johnston's Army of Tennessee about 53,000; the Union strategy aimed to erode these forces faster than recruitment or conscription could replenish them, avoiding the need for decisive annihilation battles that had eluded previous commanders.[11] This sustained offensive eroded Confederate cohesion over time, as evidenced by cumulative casualties exceeding 50,000 in the Overland Campaign alone by June, compelling resource diversion and preventing unified responses.[14] The Atlanta campaign's integration into this framework heightened its political ramifications amid Northern war weariness following stalemates like the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, compounded by Copperhead Democrats' agitation for armistice and criticism of conscription and emancipation policies.[15] President Abraham Lincoln's re-election bid in November 1864 depended on tangible victories to reaffirm the war's winnability, countering Democratic platforms favoring negotiated peace and leveraging Union numerical superiority.[16] Sherman's September 2 capture of Atlanta, resulting from Grant's pinning strategy that isolated Johnston's army without eastern reinforcements, provided a morale surge and electoral boost, demonstrating progress toward Confederate exhaustion independent of slavery-focused rhetoric.[12] Without such outcomes, sustained offensives risked bolstering opposition narratives of futile bloodshed, potentially yielding a peace settlement preserving Southern independence.[15]Opposing Forces and Command

Union Armies under Sherman

Major General William T. Sherman directed the Union effort through the Military Division of the Mississippi, consolidating three armies that fielded roughly 110,000 men near Chattanooga at the campaign's start on May 5, 1864.[1] This force comprised the Army of the Cumberland, commanded by Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas and serving as the primary element with its battle-hardened infantry divisions; the Army of the Tennessee under Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson, which provided mobile flanking capabilities drawing from western theater veterans; and the Army of the Ohio led by Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield, offering additional maneuver options with its comparatively lighter but adaptable units.[1] Sherman's unified command structure facilitated coordinated operations across these armies, emphasizing mutual support in maneuvers rather than isolated engagements.[17] Effective combat strength emphasized infantry, totaling over 90,000 across the armies, supplemented by about 10,000 cavalry for screening and reconnaissance, and an artillery reserve of 254 guns distributed among the commands for siege and field support.[18] Logistical preparations were critical to sustaining this mass, with Sherman integrating specialized rail repair crews—pioneers and engineers—who reconstructed tracks from Chattanooga southward as advances progressed, mitigating the challenges of Georgia's rugged terrain and Confederate sabotage.[19] Daily supply demands strained the system, targeting 130 carloads forwarded via limited assets of around 60 locomotives and 600 cars, covering rations, ammunition, and forage for tens of thousands of men and draft animals essential for wagon trains carrying 15-20 days' provisions per division.[19] These innovations in mobile logistics underscored Sherman's focus on operational endurance, enabling prolonged pressure without overextension despite the extended supply lines vulnerable to raids.[20]Confederate Army of Tennessee under Johnston

The Confederate Army of Tennessee, commanded by General Joseph E. Johnston upon assuming control in December 1863, entered the Atlanta Campaign in May 1864 with approximately 50,000 to 55,000 effectives entrenched at Dalton, Georgia, a figure significantly inferior to the Union forces arrayed against it.[21][6] This numerical vulnerability stemmed from prior defeats at Chattanooga, which had depleted ranks and strained logistics, leaving the army reliant on fortifications and terrain for defense.[22] Organized into three infantry corps under Lt. Gens. Leonidas Polk, William J. Hardee, and John B. Hood, the army was supported by Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler's cavalry for screening and reconnaissance, though overall cavalry strength remained limited at around 5,000 men.[23] Artillery assets were hampered by shortages, with Confederate ordnance production unable to match Union capabilities, compelling reliance on captured pieces and fixed defenses rather than mobile batteries.[24] Morale, initially eroded by Braxton Bragg's earlier failures, showed improvement under Johnston's leadership through reorganization and avoidance of reckless engagements, yet persisted as a vulnerability amid ongoing desertions and supply constraints in north Georgia.[25][22] Johnston's defensive posture emphasized a Fabian strategy of attrition, withdrawing along interior lines to prepared positions while inflicting costs on Sherman's advancing armies through skirmishes and natural obstacles, rooted in intimate terrain knowledge and the recognition that decisive battle risked annihilation given supply lines vulnerable to Union raids.[21] This approach prioritized preserving combat effectiveness over territorial retention, exploiting Georgia's hilly topography and rail networks for reinforcement, though it exposed the army to gradual erosion from Sherman's flanking maneuvers.[26]Johnston's Fabian Defense

Initial Advances and Flanking Maneuvers (May 7–June 4, 1864)

On May 7, 1864, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman launched the Atlanta campaign by directing his combined armies—totaling approximately 98,000 men under Maj. Gens. George H. Thomas, James B. McPherson, and John M. Schofield—from positions around Chattanooga, Tennessee, toward Confederate forces entrenched at Dalton, Georgia.[1] Sherman employed a demonstration against Mill Creek Gap and Rocky Face Ridge to fix Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee in place, while ordering McPherson's Army of the Tennessee to execute a wide flanking march through Snake Creek Gap to threaten Resaca and the Western & Atlantic Railroad.[3] This maneuver compelled Johnston, commanding about 53,000 Confederates, to withdraw southward from Dalton during the night of May 12–13 to defend the rail junction at Resaca.[27] The ensuing Battle of Resaca, fought May 13–15, featured Union assaults against fortified Confederate lines along Camp Creek and the Oostanaula River, with McPherson's forces crossing the river to probe Johnston's right flank.[28] Despite initial Union gains, including the capture of portions of the railroad, coordinated Confederate counterattacks under Lt. Gens. Leonidas Polk and John Bell Hood repulsed the advances, leading Sherman to halt major offensives after sustaining heavier losses.[27] Total casualties amounted to approximately 2,747 Union and 2,800 Confederate killed, wounded, or missing, reflecting the defensive advantages of Johnston's entrenchments without decisive results for either side.[28] Johnston continued his tactical retreat, falling back across the Oostanaula River to positions near Cassville by May 16–18, where he initially planned a counterattack against Sherman's dispersed pursuers.[29] On May 19, during a council with corps commanders, Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee advocated for an assault, but Polk and Hood reported perceived Union threats on their flanks—later deemed exaggerated—citing vulnerabilities in the line southeast of the town, which prompted Johnston to order a general withdrawal across the Etowah River that evening without engaging in major combat.[29] Skirmishing around Cassville resulted in minimal casualties, preserving Confederate strength while allowing Sherman to repair rail communications.[3] Over the three weeks from May 7 to early June, Sherman's forces advanced roughly 60 miles from Chattanooga to the Etowah River line, methodically outflanking Johnston's positions and severing rail links north of Resaca, though both armies remained largely intact for subsequent operations.[1] This phase exemplified Johnston's Fabian strategy of trading space for time, yielding ground without risking annihilation, while Sherman's superior numbers and logistics enabled relentless pressure absent large-scale frontal assaults.[3]Defensive Stands at New Hope Church, Dallas, and Pickett's Mill (May 25–June 4)

Following Sherman's flanking maneuver across the Etowah River, detected on May 25, 1864, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston withdrew his Army of Tennessee from Allatoona Pass to interior lines centered on New Hope Church, approximately 8 miles southwest, adopting shorter, more defensible positions in the rugged, forested terrain of Paulding County, Georgia.[30] This shift allowed Johnston to concentrate his forces against Sherman's dispersed columns, leveraging natural obstacles and hasty entrenchments to counter Union probes while preserving manpower.[6] Union Major General Joseph Hooker's XX Corps encountered Confederate resistance at New Hope Church on May 25–26, advancing through boggy woods dubbed the "Hell Hole" by Federal troops due to its miry soil and dense undergrowth, exacerbated by late-May rains that turned paths into quagmires and hindered artillery and maneuver.[30] Hooker's frontal assault on Lieutenant General John Bell Hood's entrenched corps on May 27 resulted in approximately 1,665 Union casualties against 400 Confederate losses, highlighting the defensive advantage of breastworks and elevated positions amid the downpours, which soaked ammunition and fatigued attackers without yielding a breakthrough.[30][31] On May 27, Union Major General Oliver O. Howard's IV Corps, under Brigadier General William B. Hazen's division, probed Confederate right flank positions at Pickett's Mill, where Major General Patrick Cleburne's division held fortified lines along a wooded ridge; the assault inflicted about 1,580 Union casualties (including 230 killed and 319 missing) versus roughly 500 Confederate, as terrain funneled attackers into kill zones defended by entrenched infantry and artillery, with rainfall further delaying reinforcements and complicating Federal coordination.[32] Skirmishing extended to Dallas through May 28–June 1, where additional Union attempts against Johnston's pivoting lines incurred further losses without dislodging the Confederates, whose interior positioning enabled rapid shifts to meet threats.[3] These engagements demonstrated the high cost of direct assaults on prepared defenses in the rain-saturated "Hell Hole" region, where mud and elevation favored defenders, compelling Sherman to resume flanking operations by early June and gradually forcing Johnston's withdrawal toward Marietta without a decisive Union penetration by June 4.[33] Total Union casualties in the sector exceeded 3,000, underscoring Johnston's Fabian tactics of trading space for attrition while maintaining army cohesion.[3]Operations Toward Marietta and Kennesaw Mountain (June 9–July 3)

Following the engagements around Dallas, Union forces under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman advanced toward Marietta, Georgia, beginning on June 9, 1864, as Johnston's Army of Tennessee withdrew into entrenched positions in the area to contest the approaches to Atlanta.[34] Johnston established a series of defensive lines anchored on natural features, including Pine Mountain, Lost Mountain, and Brushy Mountain, leveraging terrain and fortifications to counter Sherman's numerical superiority of approximately 100,000 to Johnston's 60,000.[35] These positions formed part of a broader entrenchment extending from Marietta southward toward Kennesaw Mountain, designed to inflict attrition while protecting supply lines.[36] On June 14, Union artillery fire during reconnaissance at Pine Mountain killed Confederate Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk, prompting skirmishes as Sherman sought to outflank the Confederate left.[33] Over the next days, from June 15 to 18, Sherman's probing attacks and flanking maneuvers compelled Johnston to shorten his lines incrementally, with fighting at Pine Hill, Lost Mountain, and Brushy Mountain resulting in Union advances but no decisive breakthroughs; Confederate forces repelled assaults through prepared works, maintaining cohesion while retreating to stronger ground.[37] By June 19, Johnston had consolidated into a formidable 10-to-18-mile line of entrenchments running from Marietta along Kennesaw Mountain's spurs, including Little Kennesaw and Pigeon Hill, where engineering efforts created interconnected redoubts and abatis to maximize defensive advantages against Sherman's preferred turning movements.[38][36] Sherman continued attempts to maneuver around the Confederate right flank southward, but on June 22, at Kolb's Farm near Powder Springs Road, Lt. Gen. John B. Hood's Confederate corps launched an uncoordinated assault against elements of Maj. Gen. John Schofield's Army of the Ohio and Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker's XX Corps from the Army of the Cumberland; the attack was repulsed after sharp fighting in wooded terrain, with Union forces holding their positions and inflicting disproportionate Confederate losses in a skirmish that highlighted the risks of offensive action against prepared Union lines.[39] This engagement delayed Sherman's flanking but demonstrated the Confederate line's vulnerability to overextension, as Hood's probe failed to disrupt the Union advance.[40] Facing the entrenched Kennesaw position, which terrain rendered difficult to fully envelop without excessive delay, Sherman deviated from his campaign-long strategy of maneuver on June 24 by ordering limited frontal assaults for June 27, aiming to fix Johnston in place, probe for weakness, and generate momentum amid growing expectations for progress in the Eastern theater's stalemates.[38] The assaults targeted the Confederate center and left: Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson's Army of the Tennessee struck Little Kennesaw unsuccessfully, while Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas's Army of the Cumberland mounted the main effort at Pigeon Hill and Cheatham Hill (later called the "Dead Angle" for its intense close-quarters combat), where Federal troops briefly gained ground but were driven back by massed volleys and counterattacks.[41] Schofield's forces demonstrated but did not press heavily; the fighting yielded a tactical Confederate victory, with Union casualties estimated at 3,000 killed, wounded, or missing against 1,000 for Johnston's forces, underscoring the high cost of direct assaults on fortified heights.[42][41] In the days following June 27, Sherman shifted forces to resume flanking operations southward around the Confederate right, probing toward the Chattahoochee River by July 3 and positioning for a crossing that would threaten Atlanta's outer defenses, though Johnston adjusted his lines to cover the river approaches without yielding the field.[1] This phase exemplified Johnston's Fabian strategy of successive withdrawals under pressure, trading space for time while imposing steady attrition, but it also exposed the limitations of maneuver in constricted terrain, prompting Sherman's rare recourse to partial direct pressure.[38]Command Transition and Hood's Aggression

Davis's Removal of Johnston (July 17)

On July 17, 1864, Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered the relief of General Joseph E. Johnston from command of the Army of Tennessee, citing his failure to advance against Union forces or provide concrete plans for offensive action.[43] The directive arrived via telegram from Adjutant and Inspector General Samuel Cooper, instructing Johnston to relinquish authority immediately to Lieutenant General John Bell Hood, who assumed command that evening.[44] Davis's decision stemmed from mounting frustration in Richmond over Johnston's strategy, which had resulted in a steady retreat of approximately 80 miles southward from Dalton, Georgia, since early May, without a decisive engagement to halt Major General William T. Sherman's advance.[3] Johnston's defensive approach preserved Confederate strength, inflicting heavier proportional losses on the Union army; official returns indicate Confederate casualties under his command from May to mid-July totaled around 6,000, compared to over 20,000 Union losses across engagements like Resaca, New Hope Church, and Kennesaw Mountain.[27] However, reports to Davis portrayed Johnston's intentions as evasive, with no detailed proposals for counterattacks despite Sherman's flanking maneuvers forcing repeated withdrawals. The abrupt change elicited dismay among the Army of Tennessee's ranks, where Johnston enjoyed high regard for restoring discipline and morale following earlier defeats; soldiers' accounts, such as those from private Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee Infantry, reflect a sense of foreboding and loss of confidence in the shift to Hood's more aggressive style.[22][45] This transition marked a pivotal pivot from Fabian tactics to direct confrontation, amid reports of eroding civilian and political support for Johnston's perceived passivity.[46]Hood's Initial Assaults: Peachtree Creek and Atlanta (July 20–22)

Upon assuming command of the Army of Tennessee on July 18, 1864, Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood adopted an aggressive offensive strategy, departing from Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's prior emphasis on defensive attrition to counter Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's flanking maneuvers toward Atlanta.[4] Hood ordered immediate assaults to exploit perceived Union vulnerabilities during their piecemeal crossings of obstacles north of the city.[47] This shift prioritized direct Napoleonic-style attacks over prolonged entrenchment, despite the Confederate army's recent losses and Sherman's numerical superiority of approximately 80,000 to 50,000 effectives.[3] On July 20, Hood directed Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee's and Lt. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart's corps—totaling about 20,000 men—to strike the Army of the Cumberland under Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas as it bridged Peachtree Creek, aiming for an echelon attack starting at 1:00 p.m. to sever Union lines.[48] However, delays in coordination, exacerbated by Hardee's failure to reconnoiter adequately and Stewart's late arrival, fragmented the assault into uncoordinated waves against Thomas's fortified positions, including breastworks and artillery.[49] The Confederate attack faltered amid heavy fire, with troops like Maj. Gen. William W. Loring's division suffering severe repulses; Union forces, numbering around 20,000 engaged, held firm with prepared defenses.[49] Casualties totaled approximately 1,600 Union (killed, wounded, and missing) against 2,500 Confederate, highlighting the tactical inefficiency of piecemeal engagements against entrenched foes.[49] Two days later, on July 22, Hood launched a larger assault targeting Sherman's exposed left flank held by Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson's Army of the Tennessee, marching Hardee's corps under cover to strike from the south while holding other forces in reserve.[4] Hardee's troops initially penetrated Union lines near Bald Hill, capturing artillery and threatening a breakthrough, but McPherson, attempting to rally counterattacking units, was killed by Confederate skirmishers from Maj. Gen. William H. T. Walker's division around midday.[50] Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard assumed command, and Maj. Gen. John A. Logan led improvised counterattacks that exploited Confederate disorganization, restoring the Union position by evening despite fierce hand-to-hand fighting.[4] The battle inflicted roughly 3,700 Union casualties against over 5,000 Confederate, with Hood's failure to commit reserves fully or coordinate across corps amplifying losses in open assaults against Sherman's adapting defenses.[4] These engagements demonstrated Hood's offensive doctrine yielding disproportionate Confederate attrition, undermining the army's defensive viability compared to Johnston's earlier success in minimizing losses through maneuver and entrenchment.[3]

Escalation and Siege Operations

Ezra Church and Utoy Creek (July 28–August 7)

On July 28, 1864, Confederate General John Bell Hood ordered an assault against the Union Army of the Tennessee under Major General Oliver O. Howard, which was advancing westward from Atlanta toward the Georgia Railroad to sever Confederate supply lines.[51] Major General Joseph Wheeler's cavalry conducted a diversionary raid northward to distract Union forces, while Hood committed four infantry divisions under Lieutenant General Stephen D. Lee to envelop Howard's exposed right flank near Ezra Church, a Methodist meeting house west of the city.[52] The Confederate attacks, launched in uncoordinated waves against hastily entrenched Union positions, were repulsed after intense fighting, resulting in approximately 3,000 Confederate casualties compared to fewer than 650 Union losses.[53] This tactical defeat further depleted Hood's already outnumbered army, which had suffered heavily from prior aggressive engagements.[52] Following the setback at Ezra Church, Union commander Major General William T. Sherman shifted focus southward on August 5–7, directing probes by the Army of the Cumberland under Major General George H. Thomas toward Utoy Creek to threaten the Macon and Western Railroad.[54] Confederate forces, entrenched along the creek under Hood's overall command, repelled the Union advances through prepared defenses and counterattacks, inflicting roughly 850–1,000 casualties on Sherman's troops while sustaining about 345 losses themselves.[54] Although the Union effort yielded minimal territorial gains and failed to disrupt rail communications, it compelled Hood to redistribute his depleted divisions, highlighting vulnerabilities in Confederate manpower and positioning amid ongoing supply pressures from encirclement threats.[54] Hood's pattern of high-cost defensive stands, rather than Johnston's prior Fabian retreats, accelerated attrition in the Army of Tennessee, with effective strength dropping below 40,000 effectives by late July due to cumulative battle losses exceeding 10,000 since mid-July.[55]

Flanking Maneuvers and Jonesborough (August 14–September 1)

Following the inconclusive actions at Utoy Creek, Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman sought to sever the Macon and Western Railroad, Atlanta's final supply artery, by employing cavalry raids to probe Confederate defenses while preparing a larger flanking movement southward. On August 18, Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick departed Federal lines south of Atlanta with approximately 4,500 troopers, striking the railroad near Jonesborough and Lovejoy's Station over the next four days; his command destroyed several miles of track, bridges, and telegraph lines before withdrawing on August 22 amid Confederate resistance from Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler's cavalry.[56][55] This raid inflicted repair delays estimated at up to ten days but failed to hold the line, prompting Sherman to commit his full 60,000-man force in a bold envelopment to outflank Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood's entrenched positions east and north of the city.[57] By August 25, Sherman initiated the maneuver, directing the Army of the Tennessee under Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard to swing southeast toward the Macon line, screened by the XX Corps, while feints held Hood's attention elsewhere; over the ensuing days, Federal columns advanced 10–15 miles south, reaching positions near Rough and Ready by August 30 and compelling Hood to detach Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee's corps—bolstered by elements under Maj. Gen. Stephen D. Lee—to contest the threat.[58] Hardee entrenched about 24,000 men astride the railroad at Jonesborough, but Sherman's forces, numbering around 30,000 in the immediate sector, flanked westward during the night of August 31 after initial assaults repulsed Confederate skirmishers.[59] The ensuing Battle of Jonesborough on August 31–September 1 pitted Howard's infantry against Hardee's line in coordinated attacks; Union divisions under Brig. Gens. Jefferson C. Davis and Absalom Baird overran portions of the Confederate right after heavy artillery preparation, while flanking pressure eroded Hardee's cohesion, forcing a nighttime withdrawal toward Lovejoy's Station.[58] Confederate counterthrusts, including a desperate charge by Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne's division, inflicted losses but could not dislodge the Federals, who captured the railroad intact; total casualties reached approximately 1,149 Union (killed, wounded, missing) and 2,000 Confederate, reflecting the defensive advantage of entrenched positions offset by Sherman's numerical superiority and maneuver.[59] This decisive severance of Hood's logistics—without risking a costly urban assault—compelled the Confederate commander to abandon Atlanta that night, as sustaining his army amid depleted supplies and encirclement risks became untenable.[58]Fall of Atlanta

Evacuation and Sherman's Occupation (September 2)

Following the Union victory at Jonesborough on August 31, Confederate commander Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood recognized the untenability of holding Atlanta and issued withdrawal orders for his Army of Tennessee during the afternoon of September 1, 1864, directing the destruction of military supplies and ammunition stores before retreat.[60] Hood's forces began evacuating that evening, moving south along remaining rail lines to Macon and avoiding encirclement by Sherman's flanking maneuvers.[61] To manage the civilian population amid the Confederate pullout, Atlanta Mayor James M. Calhoun, accompanied by city council members, rode out under a white flag of truce early on September 2 to meet advancing Union pickets led by Col. John Coburn of the 33rd Indiana Infantry; Calhoun formally tendered the city's surrender, emphasizing protection for non-combatants and private property as thousands of residents—estimated at around 1,500 families—commenced a mass exodus with wagons laden with belongings.[62] [63] This orderly departure, facilitated by the truce, left Atlanta's streets and homes largely abandoned by midday, with minimal Confederate rearguard presence offering no opposition.[60] Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's forces, specifically Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum's XX Corps from the Army of the Cumberland, entered the city unopposed around noon on September 2, securing key points including the state capitol and rail depots; Sherman himself arrived later that day to oversee initial occupation logistics, establishing headquarters and deploying troops to patrol and fortify against potential raids.[60] [64] Union assessments found Atlanta's central rail junctions—connecting the Georgia Railroad, Atlanta and West Point Railroad, and Macon and Western Railroad—disrupted by prior skirmishes and sabotage but structurally operational, with machine shops and foundries like those at the Atlanta Locomotive and Car Works remaining intact for potential Union repair and use as supply nodes.[3] These facilities, vital to Confederate logistics, were immediately inventoried for conversion to Federal purposes, underscoring Atlanta's strategic value as a transportation hub despite accumulated war damage to tracks and rolling stock.Immediate Destruction and Civilian Displacement

On September 7, 1864, Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman issued orders requiring Atlanta's remaining civilians to evacuate the city within five days, providing transportation south for those sympathetic to the Confederacy and north for Union supporters.[65] This directive displaced approximately 3,000 civilians, primarily women, children, and non-combatants who had endured the preceding siege, reducing Atlanta's population from about 22,000 in spring 1864 due to earlier flight and military demands.[66] The evacuation halted normal civilian life, scattering residents as refugees toward Confederate lines or Union territories and effectively suspending the city's commercial and social functions amid ongoing military occupation.[3] To deny the Confederacy resupply capabilities, Sherman directed the systematic demolition of military infrastructure in early November 1864, targeting railroads, depots, warehouses, machine shops, and factories essential to war production.[67] Demolition efforts, supervised by Chief Engineer Orlando Poe and commencing November 11, employed explosives, battering rams, and controlled fires to raze these assets.[68] Orders specified sparing private residences, with Sherman later asserting that only designated military structures were authorized for burning.[69] However, sparks from explosions and fires spread to adjacent areas, consuming unintended structures despite efforts to contain them.[70] Union engineer Poe estimated 37 percent of the city demolished, while postwar assessments place the damage at around 40 percent, including much of the business district and portions of residential zones.[71] This targeted yet consequential destruction rendered Atlanta's industrial base inoperable for Confederate logistics, contrasting with the decentralized foraging tactics employed later in Sherman's March to the Sea.[72]Military Analysis

Casualty Figures and Tactical Outcomes

Union casualties in the Atlanta campaign, spanning May 7 to September 2, 1864, totaled 34,523, comprising 4,988 killed, 24,827 wounded, and 4,708 missing or captured, as reported by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman in his memoirs based on official returns.[55] Confederate losses for the same period are estimated at approximately 40,000, including combat deaths, wounds, captures, and significant desertions, derived from Army of Tennessee medical director reports and commander summaries that documented over 22,000 aggregate losses from Dalton to Atlanta alone.[73] These figures yield an overall casualty ratio of roughly 1:1.2 Union to Confederate, reflecting Sherman's emphasis on flanking maneuvers that conserved Union strength while exposing Confederate forces to higher-risk frontal assaults under Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood.[4] During the Johnston phase (May 7–July 16), Union forces incurred the majority of losses—estimated at over 20,000—due to repeated assaults against entrenched Confederate positions at sites like Resaca and New Hope Church, where offensive operations against prepared defenses amplified Union vulnerabilities.[6] Confederate casualties in this period were lower, around 15,000, benefiting from defensive advantages that minimized exposure.[3] In contrast, the Hood phase (July 18–September 2) reversed the dynamic, with Confederate assaults at Peachtree Creek (2,500 losses versus 1,750 Union), the Battle of Atlanta (approximately 5,500 versus 3,700 Union), and Ezra Church (over 3,000 versus 632 Union) driving disproportionate Confederate casualties exceeding 10,000 from major engagements alone.[49][74][52] Later actions at Utoy Creek and Jonesborough added smaller but cumulative losses, with Union figures at Utoy around 1,000 and Jonesborough 1,149, against Confederate estimates of 400–2,000 combined.[54]| Major Engagement | Union Casualties | Confederate Casualties |

|---|---|---|

| Peachtree Creek (July 20) | 1,750 | 2,500 |

| Battle of Atlanta (July 22) | 3,722 | 5,500 |

| Ezra Church (July 28) | 632 | 3,000+ |

| Utoy Creek (August 5–7) | ~1,000 | ~400 |

| Jonesborough (August 31–September 1) | 1,149 | ~1,750 |

Strategic Effectiveness: Maneuver vs. Direct Engagement

Sherman's strategy emphasized repeated flanking maneuvers, compelling Confederate forces under Johnston to withdraw southward without committing to costly frontal assaults until necessary. From May 7 to July 9, 1864, Sherman executed at least five major flanking operations—bypassing positions at Dalton, Resaca, Cassville, Dallas-New Hope Church, and Kennesaw Mountain—advancing Union armies approximately 100 miles from Chattanooga toward Atlanta while maintaining supply lines via the Western & Atlantic Railroad.[1][76] This approach preserved Union force cohesion, with overall campaign logistics enabling sustained mobility despite terrain challenges, as evidenced by the repair and extension of rail infrastructure paralleling advances.[77] Johnston's corresponding defensive maneuvers—systematic retreats to fortified lines—minimized direct engagements, resulting in Confederate losses under his command estimated at around 6,000–8,000 killed, wounded, or missing from May 5 to July 17, representing less than 15% attrition on an initial force of about 53,800 present for duty (augmented by 15,000 reinforcements).[1] Skirmishes at Resaca (approximately 2,500 casualties) and New Hope Church/Pickett's Mill (another 2,500 combined) accounted for most combat losses, with disease and desertion contributing further but not decisively eroding combat effectiveness, allowing the Army of Tennessee to retain operational integrity upon reaching Atlanta's outer defenses.[3] In contrast, Hood's shift to aggressive direct engagements after assuming command on July 18 accelerated Confederate depletion. Assaults at Peachtree Creek (July 20; ~2,500 losses), the Battle of Atlanta (July 22; 8,000–10,000 losses), and Ezra Church (July 28; ~3,000 losses) inflicted rapid attrition, totaling over 15,000 casualties in less than three weeks on a force already reduced to ~40,000–45,000 effectives, equating to roughly 30–35% losses post-relief and compromising subsequent defensive capabilities.[4][3] Causal analysis of outcomes reveals maneuver's empirical edge in this numerically asymmetric contest, where Union superiority in men (~100,000 vs. Confederate ~55,000) favored Sherman's operational envelopments to force territorial concessions without mutual exhaustion, while Johnston's avoidance of decisive battle extended Confederate resistance; Hood's offensive attrition, by contrast, hastened force degradation without reversing Union gains, underscoring maneuver's preservation of combat power over attritional risks for the inferior side.[77][78]Controversies in Leadership and Strategy

Debates over Johnston's Caution and Davis's Intervention