Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cavalry

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

Historically, cavalry (from the French word cavalerie, itself derived from cheval meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in the roles of reconnaissance, screening, and skirmishing, or as heavy cavalry for decisive economy of force and shock attacks. An individual soldier in the cavalry is known by a number of designations depending on era and tactics, such as a cavalryman, horseman, trooper, cataphract, knight, drabant, hussar, uhlan, mamluk, cuirassier, lancer, dragoon, samurai or horse archer. The designation of cavalry was not usually given to any military forces that used other animals or platforms for mounts, such as chariots, camels or elephants. Infantry who moved on horseback, but dismounted to fight on foot, were known in the early 17th to the early 18th century as dragoons, a class of mounted infantry which in most armies later evolved into standard cavalry while retaining their historic designation.

Cavalry had the advantage of improved mobility, and a soldier fighting from horseback also had the advantages of greater height, speed, and inertial mass over an opponent on foot. Another element of horse mounted warfare is the psychological impact a mounted soldier can inflict on an opponent.

The speed, mobility, and shock value of cavalry was greatly valued and exploited in warfare during the Ancient and Medieval eras. Some hosts were mostly cavalry, particularly in nomadic societies of Asia, notably the Huns of Attila and the later Mongol armies.[1] In Europe, cavalry became increasingly armoured (heavy), and eventually evolving into the mounted knights of the medieval period. During the 17th century, cavalry in Europe discarded most of its armor, which was ineffective against the muskets and cannons that were coming into common use, and by the mid-18th century armor had mainly fallen into obsolescence, although some regiments retained a small thickened cuirass that offered protection against lances, sabres, and bayonets; including some protection against a shot from distance.

In the interwar period many cavalry units were converted into motorized infantry and mechanized infantry units, or reformed as tank troops. The cavalry tank or cruiser tank was one designed with a speed and purpose beyond that of infantry tanks and would subsequently develop into the main battle tank. Nonetheless, some cavalry still served during World War II (notably in the Red Army, the Mongolian People's Army, the Royal Italian Army, the Royal Hungarian Army, the Romanian Army, the Polish Land Forces, and German light reconnaissance units within the Waffen SS).

Most cavalry units that are horse-mounted in modern armies serve in purely ceremonial roles, or as mounted infantry in difficult terrain such as mountains or heavily forested areas. Modern usage of the term generally refers to units performing the role of reconnaissance, surveillance, and target acquisition (analogous to historical light cavalry) or main battle tank units (analogous to historical heavy cavalry).

Role

[edit]Historically, cavalry was divided into light cavalry and heavy cavalry. The differences were their roles in combat, the size of their mounts, and how much armor was worn by the mount and rider.

Heavy cavalry, such as Byzantine cataphracts and knights of the Early Middle Ages in Europe, were used as shock troops, charging the main body of the enemy at the height of a battle; in many cases their actions decided the outcome of the battle, hence the later term battle cavalry.[2] Light cavalry, such as horse archers, hussars, and Cossack cavalry, were assigned all the numerous roles that were ill-suited to more narrowly focused heavy forces. This includes scouting, deterring enemy scouts, foraging, raiding, skirmishing, pursuit of retreating enemy forces, screening of retreating friendly forces, linking separated friendly forces, and countering enemy light forces in all these same roles.

Light and heavy cavalry roles continued through early modern warfare, but armor was reduced, with light cavalry mostly unarmored. Yet many cavalry units still retained cuirasses and helmets for their protective value against sword and bayonet strikes, and the morale boost these provide to the wearers, despite the actual armour giving little protection from firearms. By this time the main difference between light and heavy cavalry was in their training and weight; the former was regarded as best suited for harassment and reconnaissance, while the latter was considered best for close-order charges. By the start of the 20th century, as total battlefield firepower increased, cavalry increasingly tended to become dragoons in practice, riding mounted between battles, but dismounting to fight as infantry, even though retaining unit names that reflected their older cavalry roles. Military conservatism was however strong in most continental cavalry during peacetime and in these dismounted action continued to be regarded as a secondary function until the outbreak of World War I in 1914.[3]

With the development of armored warfare, the heavy cavalry role of decisive shock troops had been taken over by armored units employing medium and heavy tanks, and later main battle tanks.[4] Despite horse-borne cavalry becoming obsolete, the term cavalry is still used, referring in modern times to units continuing to fulfill the traditional light cavalry roles, employing fast armored cars, light tanks, and infantry fighting vehicles instead of horses, while air cavalry employs helicopters.

Early history

[edit]Origins

[edit]

Before the Iron Age, the role of cavalry on the battlefield was largely performed by light chariots. The chariot originated with the Sintashta-Petrovka culture in Central Asia and spread by nomadic or semi-nomadic Indo-Iranians.[5] The chariot was quickly adopted by settled peoples both as a military technology and an object of ceremonial status, especially by the pharaohs of the New Kingdom of Egypt from 1550 BC as well as the Assyrian army and Babylonian royalty.[6]

The power of mobility given by mounted units was recognized early on, but was offset by the difficulty of raising large forces and by the inability of horses (then mostly small) to carry heavy armor. Nonetheless, there are indications that, from the 15th century BC onwards, horseback riding was practiced amongst the military elites of the great states of the ancient Near East, most notably those in Egypt, Assyria, the Hittite Empire, and Mycenaean Greece.[7]

Cavalry techniques, and the rise of true cavalry, were an innovation of equestrian nomads of the Eurasian Steppe and pastoralist tribes such as the Iranic Parthians and Sarmatians. Together with a core of armoured lancers,[8] these were predominantly horse archers using the Parthian shot tactic.[9]

The photograph straight above shows Assyrian cavalry from reliefs of 865–860 BC. At this time, the men had no spurs, saddles, saddle cloths, or stirrups. Fighting from the back of a horse was much more difficult than mere riding. The cavalry acted in pairs; the reins of the mounted archer were controlled by his neighbour's hand. Even at this early time, cavalry used swords, shields, spears, and bows. The sculpture implies two types of cavalry, but this might be a simplification by the artist. Later images of Assyrian cavalry show saddle cloths as primitive saddles, allowing each archer to control his own horse.[10]

As early as 490 BC a breed of large horses was bred in the Nisaean plain in Media to carry men with increasing amounts of armour (Herodotus 7,40 & 9,20), but large horses were still very exceptional at this time. By the fourth century BC the Chinese during the Warring States period (403–221 BC) began to use cavalry against rival states,[11] and by 331 BC when Alexander the Great defeated the Persians the use of chariots in battle was obsolete in most nations; despite a few ineffective attempts to revive scythed chariots. The last recorded use of chariots as a shock force in continental Europe was during the Battle of Telamon in 225 BC.[12] However, chariots remained in use for ceremonial purposes such as carrying the victorious general in a Roman triumph, or for racing.

Outside of mainland Europe, the southern Britons met Julius Caesar with chariots in 55 and 54 BC, but by the time of the Roman conquest of Britain a century later chariots were obsolete, even in Britannia. The last mention of chariot use in Britain was by the Caledonians at the Mons Graupius, in 84 AD.

Ancient Greece: city-states, Thebes, Thessaly and Macedonia

[edit]

During the classical Greek period, cavalry was usually limited to citizens who could afford expensive war-horses. Three types of cavalry became common: light cavalry - who armed with javelins could harass and skirmish; heavy cavalry - using lances and having the ability to close in on their opponents; and finally those whose equipment allowed them to fight either on horseback or foot. The role of horsemen did, however, remain secondary to that of the hoplites or heavy infantry who comprised the main strength of the citizen levies of the various city states.[13]

Cavalry played a relatively minor role in ancient Greek city-states, with conflicts decided by massed armored infantry. However, Thebes produced Pelopidas, their first great cavalry commander, whose tactics and skills were absorbed by Philip II of Macedon when Philip was a guest-hostage in Thebes. Thessaly was widely known for producing competent cavalrymen,[14] and later experiences in wars both with and against the Persians taught the Greeks the value of cavalry in skirmishing and pursuit. The Athenian author and soldier Xenophon in particular advocated the creation of a small but well-trained cavalry force; to that end, he wrote several manuals on horsemanship and cavalry operations.[15]

The Macedonian kingdom in the north, on the other hand, developed a strong cavalry force that culminated in the hetairoi (Companion cavalry)[16] of Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great. In addition to these heavy cavalry, the Macedonian army also employed lighter horsemen[17] called prodromoi for scouting and screening, as well as the Macedonian pike phalanx and various kinds of light infantry. There were also the Ippiko (or "Horserider"), Greek "heavy" cavalry, armed with kontos (or cavalry lance), and sword. These wore leather armour or mail plus a helmet. They were medium rather than heavy cavalry, meaning that they were better suited to be scouts, skirmishers, and pursuers rather than front line fighters. The effectiveness of this combination of cavalry and infantry helped to break enemy lines and was most dramatically demonstrated in Alexander's conquests of Persia, Bactria, and northwestern India.[18]

Roman Republic and early Empire

[edit]

The cavalry in the early Roman Republic remained the preserve of the wealthy landed class known as the equites—men who could afford the expense of maintaining a horse in addition to arms and armor heavier than those of the common legions. Horses were provided by the Republic and could be withdrawn if neglected or misused, together with the status of being a cavalryman.[19]

As the class grew to be more of a social elite instead of a functional property-based military grouping, the Romans began to employ Italian socii for filling the ranks of their cavalry.[20] The weakness of Roman cavalry was demonstrated by Hannibal Barca during the Second Punic War where he used his superior mounted forces to win several battles. The most notable of these was the Battle of Cannae, where he inflicted a catastrophic defeat on the Romans. At about the same time the Romans began to recruit foreign auxiliary cavalry from among Gauls, Iberians, and Numidians, the last being highly valued as mounted skirmishers and scouts (see Numidian cavalry). Julius Caesar had a high opinion of his escort of Germanic mixed cavalry, giving rise to the Cohortes Equitatae. Early emperors maintained an ala of Batavian cavalry as their personal bodyguards until the unit was dismissed by Galba after the Batavian Rebellion.[21]

For the most part, Roman cavalry during the early Republic functioned as an adjunct to the legionary infantry and formed only one-fifth of the standing force comprising a consular army. Except in times of major mobilisation about 1,800 horsemen were maintained, with three hundred attached to each legion.[22] The relatively low ratio of horsemen to infantry does not mean that the utility of cavalry should be underestimated, as its strategic role in scouting, skirmishing, and outpost duties was crucial to the Romans' capability to conduct operations over long distances in hostile or unfamiliar territory. On some occasions Roman cavalry also proved its ability to strike a decisive tactical blow against a weakened or unprepared enemy, such as the final charge at the Battle of Aquilonia.[23]

After defeats such as the Battle of Carrhae, the Romans learned the importance of large cavalry formations from the Parthians.[24] At the same time heavy spears and shields modelled on those favoured by the horsemen of the Greek city-states were adopted to replace the lighter weaponry of early Rome.[25] These improvements in tactics and equipment reflected those of a thousand years earlier when the first Iranians to reach the Iranian Plateau forced the Assyrians to undertake similar reform. Nonetheless, the Romans would continue to rely mainly on their heavy infantry supported by auxiliary cavalry.

Late Roman Empire and the Migration Period

[edit]

In the army of the late Roman Empire, cavalry played an increasingly important role. The Spatha, the classical sword throughout most of the 1st millennium was adopted as the standard model for the Empire's cavalry forces. By the 6th century these had evolved into lengthy straight weapons influenced by Persian and other eastern patterns.[26] Other specialist weapons during this period included javelins, long reaching lancers, axes and maces.[27]

The most widespread employment of heavy cavalry at this time was found in the forces of the Iranian empires, the Parthians and their Persian Sasanian successors. Both, but especially the former, were famed for the cataphract (fully armored cavalry armed with lances) even though the majority of their forces consisted of lighter horse archers. The West first encountered this eastern heavy cavalry during the Hellenistic period with further intensive contacts during the eight centuries of the Roman–Persian Wars. At first the Parthians' mobility greatly confounded the Romans, whose armoured close-order infantry proved unable to match the speed of the Parthians. However, later the Romans would successfully adapt such heavy armor and cavalry tactics by creating their own units of cataphracts and clibanarii.[28]

The decline of the Roman infrastructure made it more difficult to field large infantry forces, and during the 4th and 5th centuries cavalry began to take a more dominant role on the European battlefield, also in part made possible by the appearance of new, larger breeds of horses. The replacement of the Roman saddle by variants on the Scythian model, with pommel and cantle,[29] was also a significant factor as was the adoption of stirrups and the concomitant increase in stability of the rider's seat. Armored cataphracts began to be deployed in Eastern Europe and the Near East, following the precedents established by Persian forces, as the main striking force of the armies in contrast to the earlier roles of cavalry as scouts, raiders, and outflankers.[30]

The late-Roman cavalry tradition of organized units in a standing army differed fundamentally from the nobility of the Germanic invaders—individual warriors who could afford to provide their own horses and equipment. While there was no direct linkage with these predecessors the early medieval knight also developed as a member of a social and martial elite, able to meet the considerable expenses required by his role from grants of land and other incomes.[31]

Asia

[edit]Central Asia

[edit]

Xiongnu, Tujue, Avars, Kipchaks, Khitans, Mongols, Don Cossacks and the various Turkic peoples are also examples of the horse-mounted groups that managed to gain substantial successes in military conflicts with settled agrarian and urban societies, due to their strategic and tactical mobility. As European states began to assume the character of bureaucratic nation-states supporting professional standing armies, recruitment of these mounted warriors was undertaken in order to fill the strategic roles of scouts and raiders.

The best known instance of the continued employment of mounted tribal auxiliaries were the Cossack cavalry regiments of the Russian Empire. In Eastern Europe, and out onto the steppes, cavalry remained important much longer and dominated the scene of warfare until the early 17th century and even beyond, as the strategic mobility of cavalry was crucial for the semi-nomadic pastoralist lives that many steppe cultures led. Tibetans also had a tradition of cavalry warfare, in several military engagements with the Chinese Tang dynasty (618–907 AD).

Khanates of Central Asia

[edit]-

Mongol mounted archer of Genghis Khan late 12th century.

-

Tatar vanguard in Eastern Europe 13th–14th centuries.

-

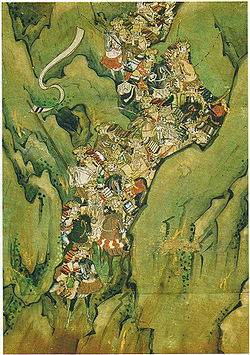

Mongols at war 14th century

East Asia

[edit]China

[edit]Further east, the military history of China, specifically northern China, held a long tradition of intense military exchange between Han Chinese infantry forces of the settled dynastic empires and the mounted nomads or "barbarians" of the north. The naval history of China was centered more to the south, where mountains, rivers, and large lakes necessitated the employment of a large and well-kept navy.

In 307 BC, King Wuling of Zhao, the ruler of the former state of Jin, ordered his commanders and troops to adopt the trousers of the nomads as well as practice the nomads' form of mounted archery to hone their new cavalry skills.[11]

The adoption of massed cavalry in China also broke the tradition of the chariot-riding Chinese aristocracy in battle, which had been in use since the ancient Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1050 BC).[32] By this time large Chinese infantry-based armies of 100,000 to 200,000 troops were now buttressed with several hundred thousand mounted cavalry in support or as an effective striking force.[33] The handheld pistol-and-trigger crossbow was invented in China in the fourth century BC;[34] it was written by the Song dynasty scholars Zeng Gongliang, Ding Du, and Yang Weide in their book Wujing Zongyao (1044 AD) that massed missile fire by crossbowmen was the most effective defense against enemy cavalry charges.[35]

On many occasions the Chinese studied nomadic cavalry tactics and applied the lessons in creating their own potent cavalry forces, while in others they simply recruited the tribal horsemen wholesale into their armies; and in yet other cases nomadic empires proved eager to enlist Chinese infantry and engineering, as in the case of the Mongol Empire and its sinicized part, the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368). The Chinese recognized early on during the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) that they were at a disadvantage in lacking the number of horses the northern nomadic peoples mustered in their armies. Emperor Wu of Han (r 141–87 BC) went to war with the Dayuan for this reason, since the Dayuan were hoarding a massive amount of tall, strong, Central Asian bred horses in the Hellenized–Greek region of Fergana (established slightly earlier by Alexander the Great). Although experiencing some defeats early on in the campaign, Emperor Wu's war from 104 BC to 102 BC succeeded in gathering the prized tribute of horses from Fergana.

Cavalry tactics in China were enhanced by the invention of the saddle-attached stirrup by at least the 4th century, as the oldest reliable depiction of a rider with paired stirrups was found in a Jin dynasty tomb of the year 322 AD.[36][37][38] The Chinese invention of the horse collar by the 5th century was also a great improvement from the breast harness, allowing the horse to haul greater weight without heavy burden on its skeletal structure.[39][40]

Korea

[edit]The horse warfare of Korea was first started during the ancient Korean kingdom Gojoseon. Since at least the 3rd century BC, there was influence of northern nomadic peoples and Yemaek peoples on Korean warfare. By roughly the first century BC, the ancient kingdom of Buyeo also had mounted warriors.[41] The cavalry of Goguryeo, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, were called Gaemamusa (개마무사, 鎧馬武士), and were renowned as a fearsome heavy cavalry force. King Gwanggaeto the Great often led expeditions into the Baekje, Gaya confederacy, Buyeo, Later Yan and against Japanese invaders with his cavalry.[42]

In the 12th century, Jurchen tribes began to violate the Goryeo–Jurchen borders, and eventually invaded Goryeo Korea. After experiencing invasion by the Jurchen, Korean general Yun Kwan realized that Goryeo lacked efficient cavalry units. He reorganized the Goryeo military into a professional army that would contain decent and well-trained cavalry units. In 1107, the Jurchen were ultimately defeated, and surrendered to Yun Kwan. To mark the victory, General Yun built nine fortresses to the northeast of the Goryeo–Jurchen borders (동북 9성, 東北 九城).

Japan

[edit]

The ancient Japanese of the Kofun period also adopted cavalry and equine culture by the 5th century AD. The emergence of the samurai aristocracy led to the development of armoured horse archers, themselves to develop into charging lancer cavalry as gunpowder weapons rendered bows obsolete. Japanese cavalry was largely made up of landowners who would be upon a horse to better survey the troops they were called upon to bring to an engagement, rather than traditional mounted warfare seen in other cultures with massed cavalry units.

An example is Yabusame (流鏑馬), a type of mounted archery in traditional Japanese archery. An archer on a running horse shoots three special "turnip-headed" arrows successively at three wooden targets.

This style of archery has its origins at the beginning of the Kamakura period. Minamoto no Yoritomo became alarmed at the lack of archery skills his samurai had. He organized yabusame as a form of practice. Currently, the best places to see yabusame performed are at the Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū in Kamakura and Shimogamo Shrine in Kyoto (during Aoi Matsuri in early May). It is also performed in Samukawa and on the beach at Zushi, as well as other locations.

Kasagake or Kasakake (笠懸, かさがけ lit. "hat shooting") is a type of Japanese mounted archery. In contrast to yabusame, the types of targets are various and the archer shoots without stopping the horse. While yabusame has been played as a part of formal ceremonies, kasagake has developed as a game or practice of martial arts, focusing on technical elements of horse archery.

South Asia

[edit]Indian subcontinent

[edit]In the Indian subcontinent, cavalry played a major role from the Gupta dynasty (320–600) period onwards. India has also the oldest evidence for the introduction of toe-stirrups.[43]

Indian literature contains numerous references to the mounted warriors of the Central Asian horse nomads, notably the Sakas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Pahlavas and Paradas. Numerous Puranic texts refer to a conflict in ancient India (16th century BC)[44] in which the horsemen of five nations, called the "Five Hordes" (pañca.ganan) or Kṣatriya hordes (Kṣatriya ganah), attacked and captured the state of Ayudhya by dethroning its Vedic King Bahu[45]

The Mahabharata, Ramayana, numerous Puranas and some foreign sources attest that the Kamboja cavalry frequently played role in ancient wars. V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar writes: "Both the Puranas and the epics agree that the horses of the Sindhu and Kamboja regions were of the finest breed, and that the services of the Kambojas as cavalry troopers were utilised in ancient wars".[46] J.A.O.S. writes: "Most famous horses are said to come either from Sindhu or Kamboja; of the latter (i.e. the Kamboja), the Indian epic Mahabharata speaks among the finest horsemen".[47]

The Mahabharata speaks of the esteemed cavalry of the Kambojas, Sakas, Yavanas and Tusharas, all of whom had participated in the Kurukshetra war under the supreme command of Kamboja ruler Sudakshin Kamboj.[48]

Mahabharata and Vishnudharmottara Purana pay especial attention to the Kambojas, Yavansa, Gandharas etc. being ashva.yuddha.kushalah (expert cavalrymen).[49] In the Mahabharata war, the Kamboja cavalry along with that of the Sakas, Yavanas is reported to have been enlisted by the Kuru king Duryodhana of Hastinapura.[50]

Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BC) attests that the Gandarian mercenaries (i.e. Gandharans/Kambojans of Gandari Strapy of Achaemenids) from the 20th strapy of the Achaemenids were recruited in the army of emperor Xerxes I (486–465 BC), which he led against the Hellas.[51] Similarly, the men of the Mountain Land from north of Kabul-River equivalent to medieval Kohistan (Pakistan), figure in the army of Darius III against Alexander at Arbela, providing a cavalry force and 15 elephants.[52] This obviously refers to Kamboja cavalry south of Hindukush.

The Kambojas were famous for their horses, as well as cavalrymen (asva-yuddha-Kushalah).[53] On account of their supreme position in horse (Ashva) culture, they were also popularly known as Ashvakas, i.e. the "horsemen"[54] and their land was known as "Home of Horses".[55] They are the Assakenoi and Aspasioi of the Classical writings, and the Ashvakayanas and Ashvayanas in Pāṇini's Ashtadhyayi. The Assakenoi had faced Alexander with 30,000 infantry, 20,000 cavalry and 30 war elephants.[56] Scholars have identified the Assakenoi and Aspasioi clans of Kunar and Swat valleys as a section of the Kambojas.[57] These hardy tribes had offered stubborn resistance to Alexander (c. 326 BC) during latter's campaign of the Kabul, Kunar and Swat valleys and had even extracted the praise of the Alexander's historians. These highlanders, designated as "parvatiya Ayudhajivinah" in Pāṇini's Astadhyayi,[58] were rebellious, fiercely independent and freedom-loving cavalrymen who never easily yielded to any overlord.[59]

The Sanskrit drama Mudra-rakashas by Visakha Dutta and the Jaina work Parishishtaparvan refer to Chandragupta's (c. 320 BC – c. 298 BC) alliance with Himalayan king Parvataka. The Himalayan alliance gave Chandragupta a formidable composite army made up of the cavalry forces of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, Kiratas, Parasikas and Bahlikas as attested by Mudra-Rakashas (Mudra-Rakshasa 2).[a] These hordes had helped Chandragupta Maurya defeat the ruler of Magadha and placed Chandragupta on the throne, thus laying the foundations of Mauryan dynasty in Northern India.

The cavalry of Hunas and the Kambojas is also attested in the Raghu Vamsa epic poem of Sanskrit poet Kalidasa.[60] Raghu of Kalidasa is believed to be Chandragupta II (Vikaramaditya) (375–413/15 AD), of the well-known Gupta dynasty.

As late as the mediaeval era, the Kamboja cavalry had also formed part of the Gurjara-Pratihara armed forces from the eighth to the 10th centuries AD. They had come to Bengal with the Pratiharas when the latter conquered part of the province.[61][62][63][64][65]

Ancient Kambojas organised military sanghas and shrenis (corporations) to manage their political and military affairs, as Arthashastra of Kautiliya as well as the Mahabharata record. They are described as Ayuddha-jivi or Shastr-opajivis (nations-in-arms), which also means that the Kamboja cavalry offered its military services to other nations as well. There are numerous references to Kambojas having been requisitioned as cavalry troopers in ancient wars by outside nations.

Mughal Empire

[edit]

The Mughal armies (lashkar) were primarily a cavalry force. The elite corps were the ahadi who provided direct service to the Emperor and acted as guard cavalry. Supplementary cavalry or dakhilis were recruited, equipped and paid by the central state. This was in contrast to the tabinan horsemen who were the followers of individual noblemen. Their training and equipment varied widely but they made up the backbone of the Mughal cavalry. Finally there were tribal irregulars led by and loyal to tributary chiefs. These included Hindus, Afghans and Turks summoned for military service when their autonomous leaders were called on by the Imperial government.[66]

European Middle Ages

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2018) |

As the quality and availability of heavy infantry declined in Europe with the fall of the Roman Empire, heavy cavalry became more effective. Infantry that lack the cohesion and discipline of tight formations are more susceptible to being broken and scattered by shock combat—the main role of heavy cavalry, which rose to become the dominant force on the European battlefield.[67]

As heavy cavalry increased in importance, it became the main focus of military development. The arms and armour for heavy cavalry increased, the high-backed saddle developed, and stirrups and spurs were added, increasing the advantage of heavy cavalry even more.[68]

This shift in military importance was reflected in an increasingly hierarchical society as well. From the late 10th century onwards heavily armed horsemen, milites or knights, emerged as an expensive elite taking centre stage both on and off the battlefield.[69] This class of aristocratic warriors was considered the "ultimate" in heavy cavalry: well-equipped with the best weapons, state-of-the-art armour from head to foot, leading with the lance in battle in a full-gallop, close-formation "knightly charge" that might prove irresistible, winning the battle almost as soon as it began.

But knights remained the minority of total available combat forces; the expense of arms, armour, and horses was only affordable to a select few. While mounted men-at-arms focused on a narrow combat role of shock combat, medieval armies relied on a large variety of foot troops to fulfill all the rest (skirmishing, flank guards, scouting, holding ground, etc.). Medieval chroniclers tended to pay undue attention to the knights at the expense of the common soldiers, which led early students of military history to suppose that heavy cavalry was the only force that mattered on medieval European battlefields. But well-trained and disciplined infantry could defeat knights.

Massed English longbowmen triumphed over French cavalry at Crécy, Poitiers and Agincourt, while at Gisors (1188), Bannockburn (1314), and Laupen (1339),[70] foot-soldiers proved they could resist cavalry charges as long as they held their formation. Once the Swiss developed their pike squares for offensive as well as defensive use, infantry started to become the principal arm. This aggressive new doctrine gave the Swiss victory over a range of adversaries, and their enemies found that the only reliable way to defeat them was by the use of an even more comprehensive combined arms doctrine, as evidenced in the Battle of Marignano. The introduction of missile weapons that required less skill than the longbow, such as the crossbow and hand cannon, also helped remove the focus somewhat from cavalry elites to masses of cheap infantry equipped with easy-to-learn weapons. These missile weapons were very successfully used in the Hussite Wars, in combination with Wagenburg tactics.

This gradual rise in the dominance of infantry led to the adoption of dismounted tactics. From the earliest times knights and mounted men-at-arms had frequently dismounted to handle enemies they could not overcome on horseback, such as in the Battle of the Dyle (891) and the Battle of Bremule (1119), but after the 1350s this trend became more marked with the dismounted men-at-arms fighting as super-heavy infantry with two-handed swords and poleaxes.[71] In any case, warfare in the Middle Ages tended to be dominated by raids and sieges rather than pitched battles, and mounted men-at-arms rarely had any choice other than dismounting when faced with the prospect of assaulting a fortified position.

Islamic States

[edit]Arabs

[edit]

The Islamic Prophet Muhammad made use of cavalry in many of his military campaigns including the Expedition of Dhu Qarad,[72] and the expedition of Zaid ibn Haritha in al-Is which took place in September, 627 AD, fifth month of 6 AH of the Islamic calendar.[73]

Early organized Arab mounted forces under the Rashidun caliphate comprised a light cavalry armed with lance and sword. Its main role was to attack the enemy flanks and rear. These relatively lightly armored horsemen formed the most effective element of the Muslim armies during the later stages of the Islamic conquest of the Levant. The best use of this lightly armed fast moving cavalry was revealed at the Battle of Yarmouk (636 AD) in which Khalid ibn Walid, knowing the skills of his horsemen, used them to turn the tables at every critical instance of the battle with their ability to engage, disengage, then turn back and attack again from the flank or rear. A strong cavalry regiment was formed by Khalid ibn Walid which included the veterans of the campaign of Iraq and Syria. Early Muslim historians have given it the name Tali'a mutaharrikah(طليعة متحركة), or the Mobile guard. This was used as an advance guard and a strong striking force to route the opposing armies with its greater mobility that give it an upper hand when maneuvering against any Byzantine army. With this mobile striking force, the conquest of Syria was made easy.[74]

The Battle of Talas in 751 AD was a conflict between the Arab Abbasid Caliphate and the Chinese Tang dynasty over the control of Central Asia. Chinese infantry were routed by Arab cavalry near the bank of the River Talas.

Until the 11th century the classic cavalry strategy of the Arab Middle East incorporated the razzia tactics of fast moving raids by mixed bodies of horsemen and infantry. Under the talented leadership of Saladin and other Islamic commanders the emphasis changed to Mamluk horse-archers backed by bodies of irregular light cavalry. Trained to rapidly disperse, harass and regroup these flexible mounted forces proved capable of withstanding the previously invincible heavy knights of the western crusaders at battles such as Hattin in 1187.[75]

Mamluks

[edit]Originating in the 9th century as Central Asian ghulams or captives utilised as mounted auxiliaries by Arab armies,[76] Mamluks were subsequently trained as cavalry soldiers rather than solely mounted-archers, with increased priority being given to the use of lances and swords.[77] Mamluks were to follow the dictates of al-furusiyya,[78] a code of conduct that included values like courage and generosity but also doctrine of cavalry tactics, horsemanship, archery and treatment of wounds.

By the late 13th century the Manluk armies had evolved into a professional elite of cavalry, backed by more numerous but less well-trained footmen.[79]

Maghreb

[edit]

The Islamic Berber states of North Africa employed elite horse mounted cavalry armed with spears and following the model of the original Arab occupiers of the region. Horse-harness and weapons were manufactured locally and the six-monthly stipends for horsemen were double those of their infantry counterparts. During the 8th century Islamic conquest of Iberia large numbers of horses and riders were shipped from North Africa, to specialise in raiding and the provision of support for the massed Berber footmen of the main armies.[80]

Maghrebi traditions of mounted warfare eventually influenced a number of sub-Saharan African polities in the medieval era. The Esos of Ikoyi, military aristocrats of the Yoruba peoples, were a notable manifestation of this phenomenon.[81]

Al-Andalus

[edit]Iran

[edit]Qizilbash, were a class of Safavid militant warriors in Iran during the 15th to 18th centuries, who often fought as elite cavalry.[82][83][84][85]

Ottoman

[edit]During its period of greatest expansion, from the 14th to 17th centuries, cavalry formed the powerful core of the Ottoman armies. Registers dated 1475 record 22,000 Sipahi feudal cavalry levied in Europe, 17,000 Sipahis recruited from Anatolia, and 3,000 Kapikulu (regular body-guard cavalry).[86] During the 18th century however the Ottoman mounted troops evolved into light cavalry serving in the thinly populated regions of the Middle East and North Africa.[87] Such frontier horsemen were largely raised by local governors and were separate from the main field armies of the Ottoman Empire. At the beginning of the 19th century modernised Nizam-I Credit ("New Army") regiments appeared, including full-time cavalry units officered from the horse guards of the Sultan.[88]

Renaissance Europe

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2018) |

Ironically, the rise of infantry in the early 16th century coincided with the "golden age" of heavy cavalry; a French or Spanish army at the beginning of the century could have up to half its numbers made up of various kinds of light and heavy cavalry, whereas in earlier medieval and later 17th-century armies the proportion of cavalry was seldom more than a quarter.

Knighthood largely lost its military functions and became more closely tied to social and economic prestige in an increasingly capitalistic Western society. With the rise of drilled and trained infantry, the mounted men-at-arms, now sometimes called gendarmes and often part of the standing army themselves, adopted the same role as in the Hellenistic age, that of delivering a decisive blow once the battle was already engaged, either by charging the enemy in the flank or attacking their commander-in-chief.

From the 1550s onwards, the use of gunpowder weapons solidified infantry's dominance of the battlefield and began to allow true mass armies to develop. This is closely related to the increase in the size of armies throughout the early modern period; heavily armored cavalrymen were expensive to raise and maintain and it took years to train a skilled horseman or a horse, while arquebusiers and later musketeers could be trained and kept in the field at much lower cost, and were much easier to recruit.

The Spanish tercio and later formations relegated cavalry to a supporting role. The pistol was specifically developed to try to bring cavalry back into the conflict, together with manoeuvres such as the caracole. The caracole was not particularly successful, however, and the charge (whether with lance, sword, or pistol) remained as the primary mode of employment for many types of European cavalry, although by this time it was delivered in much deeper formations and with greater discipline than before. The demi-lancers and the heavily armored sword-and-pistol reiters were among the types of cavalry whose heyday was in the 16th and 17th centuries. During this period the Polish Winged hussars were a dominating heavy cavalry force in Eastern Europe that initially achieved great success against Swedes, Russians, Turks and other, until repeatably beaten by either combined arms tactics, increase in firepower or beaten in melee with the Drabant cavalry of the Swedish Empire. From their last engagement in 1702 (at the Battle of Kliszów) until 1776, the obsolete Winged hussars were demoted and largely assigned to ceremonial roles. The Polish Winged hussars military prowess peaked at the Siege of Vienna in 1683, when hussar banners participated in the largest cavalry charge in history and successfully repelled the Ottoman attack.

18th-century Europe and Napoleonic Wars

[edit]

Cavalry retained an important role in this age of regularization and standardization across European armies. They remained the primary choice for confronting enemy cavalry. Attacking an unbroken infantry force head-on usually resulted in failure, but extended linear infantry formations were vulnerable to flank or rear attacks. Cavalry was important at Blenheim (1704), Rossbach (1757), Marengo (1800), Eylau and Friedland (1807), remaining significant throughout the Napoleonic Wars.

Even with the increasing prominence of infantry, cavalry still had an irreplaceable role in armies, due to their greater mobility. Their non-battle duties often included patrolling the fringes of army encampments, with standing orders to intercept suspected shirkers and deserters,[90] as well as, serving as outpost pickets in advance of the main body. During battle, lighter cavalry such as hussars and uhlans might skirmish with other cavalry, attack light infantry, or charge and either capture enemy artillery or render them useless by plugging the touchholes with iron spikes. Heavier cavalry such as cuirassiers, dragoons, and carabiniers usually charged towards infantry formations or opposing cavalry in order to rout them. Both light and heavy cavalry pursued retreating enemies, the point where most battle casualties occurred.[91]

The greatest cavalry charge of modern history was at the 1807 Battle of Eylau, when the entire 11,000-strong French cavalry reserve, led by Joachim Murat, launched a huge charge on and through the Russian infantry lines. Cavalry's dominating and menacing presence on the battlefield was countered by the use of infantry squares. The most notable examples are at the Battle of Quatre Bras and later at the Battle of Waterloo, the latter which the repeated charges by up to 9,000 French cavalrymen ordered by Michel Ney failed to break the British-Allied army, who had formed into squares.[92]

Massed infantry, especially those formed in squares were deadly to cavalry, but offered an excellent target for artillery. Once a bombardment had disordered the infantry formation, cavalry were able to rout and pursue the scattered foot soldiers. It was not until individual firearms gained accuracy and improved rates of fire that cavalry was diminished in this role as well. Even then light cavalry remained an indispensable tool for scouting, screening the army's movements, and harassing the enemy's supply lines until military aircraft supplanted them in this role in the early stages of World War I.

19th century

[edit]

Europe

[edit]By the beginning of the 19th century, European cavalry fell into four main categories:

- Cuirassiers, heavy cavalry, adorned with body armor, especially a cuirass, and primarily armed with pistols and a sword

- Dragoons, originally mounted infantry, but later regarded as medium cavalry

- Hussars, light cavalry, primarily armed with sabres

- Lancers or Uhlans, light cavalry, primarily armed with lances

There were cavalry variations for individual nations as well: France had the chasseurs à cheval; Prussia had the Jäger zu Pferde;[93] Bavaria,[94] Saxony and Austria[95] had the Chevaulegers; and Russia had Cossacks. Britain, from the mid-18th century, had Light Dragoons as light cavalry and Dragoons, Dragoon Guards and Household Cavalry as heavy cavalry. Only after the end of the Napoleonic wars were the Household Cavalry equipped with cuirasses, and some other regiments were converted to lancers. In the United States Army prior to 1862 the cavalry were almost always dragoons. The Imperial Japanese Army had its cavalry uniformed as hussars, but they fought as dragoons.

In the Crimean War, the Charge of the Light Brigade and the Thin Red Line at the Battle of Balaclava showed the vulnerability of cavalry, when deployed without effective support.[96]

Franco-Prussian War

[edit]

During the Franco-Prussian War, at the Battle of Mars-la-Tour in 1870, a Prussian cavalry brigade decisively smashed the centre of the French battle line, after skilfully concealing their approach. This event became known as Von Bredow's Death Ride after the brigade commander Adalbert von Bredow; it would be used in the following decades to argue that massed cavalry charges still had a place on the modern battlefield.[97]

Imperial expansion

[edit]Cavalry found a new role in colonial campaigns (irregular warfare), where modern weapons were lacking and the slow moving infantry-artillery train or fixed fortifications were often ineffective against indigenous insurgents (unless the latter offered a fight on an equal footing, as at Tel-el-Kebir, Omdurman, etc.). Cavalry "flying columns" proved effective, or at least cost-effective, in many campaigns—although an astute native commander (like Samori in western Africa, Shamil in the Caucasus, or any of the better Boer commanders) could turn the tables and use the greater mobility of their cavalry to offset their relative lack of firepower compared with European forces.

In 1903 the British Indian Army maintained forty regiments of cavalry, numbering about 25,000 Indian sowars (cavalrymen), with British and Indian officers.[98]

Among the more famous regiments in the lineages of the modern Indian and Pakistani armies are:

- Governor General's Bodyguard (now President's Bodyguard (India) and President's Bodyguard (Pakistan))

- Skinner's Horse (now India's 1st Horse (Skinner's Horse))

- Gardner's Lancers (now India's 2nd Lancers (Gardner's Horse))

- Hodson's Horse (now India's 3rd Horse (Hodson's)) of the Bengal Lancers fame

- 6th Bengal Cavalry (later amalgamated with 7th Hariana Lancers to form 18th King Edward's Own Cavalry) now 18th Cavalry of the Indian Army

- Royal Deccan Horse (now India's The Deccan Horse)

- Poona Horse (now India's The Poona Horse)

- Scinde Horse (now India's The Scinde Horse)

- Probyn's Horse (now Pakistan's 5th Horse)

- 19th King George V's Own Lancers (now Pakistan's 19th Lancers)

- 6th Duke of Connaught's Own Lancers (now Pakistan's 6th Lancers (Watson's Horse))

- Queen's Own Guides Cavalry (now Pakistan).

- 11th Prince Albert Victor's Own Cavalry (Frontier Force) (now 11th Cavalry (Frontier Force), Pakistan)

Several of these formations are still active, though they now are armoured formations, for example the Guides Cavalry of Pakistan.[99]

The French Army maintained substantial cavalry forces in Algeria and Morocco from 1830 until the end of World War II. Much of the Mediterranean coastal terrain was suitable for mounted action and there was a long established culture of horsemanship amongst the Arab and Berber inhabitants. The French forces included Spahis, Chasseurs d' Afrique, Foreign Legion cavalry and mounted Goumiers.[100] Both Spain and Italy raised cavalry regiments from amongst the indigenous horsemen of their North African territories (see regulares, Italian Spahis[101] and savari respectively).

Imperial Germany employed mounted formations in South West Africa as part of the Schutztruppen (colonial army) garrisoning that territory.[102]

United States

[edit]

In the early American Civil War the regular United States Army mounted rifle, dragoon, and two existing cavalry regiments were reorganized and renamed cavalry regiments, of which there were six.[103] Over a hundred other federal and state cavalry regiments were organized, but the infantry played a much larger role in many battles due to its larger numbers, lower cost per rifle fielded, and much easier recruitment. However, cavalry saw a role as part of screening forces and in foraging and scouting. The later phases of the war saw the Federal army developing a truly effective cavalry force fighting as scouts, raiders, and, with repeating rifles, as mounted infantry. The distinguished 1st Virginia Cavalry ranks as one of the most effectual and successful cavalry units on the Confederate side. Noted cavalry commanders included Confederate general J.E.B. Stuart, Nathan Bedford Forrest, and John Singleton Mosby (a.k.a. "The Grey Ghost") and on the Union side, Philip Sheridan and George Armstrong Custer.[104] Post Civil War, as the volunteer armies disbanded, the regular army cavalry regiments increased in number from six to ten, among them Custer's U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment of Little Bighorn fame, and the African-American U.S. 9th Cavalry Regiment and U.S. 10th Cavalry Regiment. The black units, along with others (both cavalry and infantry), collectively became known as the Buffalo Soldiers. According to Robert M. Utley:

- the frontier army was a conventional military force trying to control, by conventional military methods, a people that did not behave like conventional enemies and, indeed, quite often were not enemies at all. This is the most difficult of all military assignments, whether in Africa, Asia, or the American West.[105]

These regiments, which rarely took the field as complete organizations, served throughout the American Indian Wars through the close of the frontier in the 1890s. Volunteer cavalry regiments like the Rough Riders consisted of horsemen such as cowboys, ranchers and other outdoorsmen, that served as a cavalry in the United States Military.[106]

Developments 1900–1914

[edit]

At the beginning of the 20th century, all armies still maintained substantial cavalry forces, although there was contention over whether their role should revert to that of mounted infantry (the historic dragoon function). With motorised vehicles and aircraft still under development, horse mounted troops remained the only fully mobile forces available for manoeuvre warfare until 1914.[107]

United Kingdom

[edit]Following the experience of the South African War of 1899–1902 (where mounted Boer citizen commandos fighting on foot from cover proved more effective than regular cavalry employed on horseback), the British Army withdrew lances for all but ceremonial purposes and placed a new emphasis on training for dismounted action in 1903. Lances were however readopted for active service in 1912.[108]

Russia

[edit]In 1882, the Imperial Russian Army converted all its line hussar and lancer regiments to dragoons, with an emphasis on mounted infantry training. In 1910 these regiments reverted to their historic roles, designations and uniforms.[109]

Germany

[edit]By 1909, official regulations dictating the role of the Imperial German cavalry had been revised to indicate an increasing realization of the realities of modern warfare. The massive cavalry charge in three waves which had previously marked the end of annual maneuvers was discontinued and a new emphasis was placed in training on scouting, raiding and pursuit; rather than main battle involvement.[110] The perceived importance of cavalry was however still evident, with thirteen new regiments of mounted rifles (Jäger zu Pferde) being raised shortly before the outbreak of war in 1914.[111]

France

[edit]In spite of significant experience in mounted warfare in Morocco during 1908–14, the French cavalry remained a highly conservative institution.[112] The traditional tactical distinctions between heavy, medium, and light cavalry branches were retained.[113] French cuirassiers wore breastplates and plumed helmets unchanged from the Napoleonic period, during the early months of World War I.[114] Dragoons were similarly equipped, though they did not wear cuirasses and did carry lances.[115] Light cavalry were described as being "a blaze of colour". French cavalry of all branches were well mounted and were trained to change position and charge at full gallop.[116] One weakness in training was that French cavalrymen seldom dismounted on the march and their horses suffered heavily from raw backs in August 1914.[117]

First World War

[edit]Opening stages

[edit]

Europe 1914

[edit]In August 1914, all combatant armies still retained substantial numbers of cavalry and the mobile nature of the opening battles on both Eastern and Western Fronts provided a number of instances of traditional cavalry actions, though on a smaller and more scattered scale than those of previous wars. The 110 regiments of Imperial German cavalry, while as colourful and traditional as any in peacetime appearance,[118] had adopted a practice of falling back on infantry support when any substantial opposition was encountered.[119] These cautious tactics aroused derision amongst their more conservative French and Russian opponents[120] but proved appropriate to the new nature of warfare. A single attempt by the German army, on 12 August 1914, to use six regiments of massed cavalry to cut off the Belgian field army from Antwerp floundered when they were driven back in disorder by rifle fire.[121] The two German cavalry brigades involved lost 492 men and 843 horses in repeated charges against dismounted Belgian lancers and infantry.[122] One of the last recorded charges by French cavalry took place on the night of 9/10 September 1914 when a squadron of the 16th Dragoons overran a German airfield at Soissons, while suffering heavy losses.[123] Once the front lines stabilised on the Western Front with the start of Trench Warfare, a combination of barbed wire, uneven muddy terrain, machine guns and rapid fire rifles proved deadly to horse mounted troops and by early 1915 most cavalry units were no longer seeing front line action.

On the Eastern Front, a more fluid form of warfare arose from flat open terrain favorable to mounted warfare. On the outbreak of war in 1914 the bulk of the Russian cavalry was deployed at full strength in frontier garrisons and, during the period that the main armies were mobilizing, scouting and raiding into East Prussia and Austrian Galicia was undertaken by mounted troops trained to fight with sabre and lance in the traditional style.[124] On 21 August 1914 the 4th Austro-Hungarian 4th Cavalry Division under Edmund Ritter von Zaremba clashed with the Russian 10th Cavalry Division under general Fyodor Arturovich Keller in the Battle of Jaroslawice,[125] in what was arguably the final historic battle to involve thousands of horsemen on both sides.[126] While this was the last massed cavalry encounter on the Eastern Front, the absence of good roads limited the use of mechanized transport and even the technologically advanced Imperial German Army continued to deploy up to twenty-four horse-mounted divisions in the East, as late as 1917.[127]

Europe 1915–1918

[edit]

For the remainder of the War on the Western Front, cavalry had virtually no role to play. The British and French armies dismounted many of their cavalry regiments and used them in infantry and other roles: the Life Guards for example spent the last months of the War as a machine gun corps; and the Australian Light Horse served as light infantry during the Gallipoli campaign. In September 1914 cavalry comprised 9.28% of the total manpower of the British Expeditionary Force in France—by July 1918 this proportion had fallen to 1.65%.[128] As early as the first winter of the war most French cavalry regiments had dismounted a squadron each, for service in the trenches.[129] The French cavalry numbered 102,000 in May 1915 but had been reduced to 63,000 by October 1918.[130] The German Army dismounted nearly all their cavalry in the West, maintaining only one mounted division on that front by January 1917.

Italy entered the war in 1915 with thirty regiments of line cavalry, lancers and light horse. While employed effectively against their Austro-Hungarian counterparts during the initial offensives across the Isonzo River, the Italian mounted forces ceased to have a significant role as the front shifted into mountainous terrain. By 1916 most cavalry machine-gun sections and two complete cavalry divisions had been dismounted and seconded to the infantry.[131]

Some cavalry were retained as mounted troops in reserve behind the lines, in anticipation of a penetration of the opposing trenches that it seemed would never come. Tanks, introduced on the Western Front by the British in September 1916 during the Battle of the Somme, had the capacity to achieve such breakthroughs but did not have the reliable range to exploit them. In their first major use at the Battle of Cambrai (1917), the plan was for a cavalry division to follow behind the tanks, however they were not able to cross a canal because a tank had broken the only bridge.[132] On a few other occasions, throughout the war, cavalry were readied in significant numbers for involvement in major offensives; such as in the Battle of Caporetto and the Battle of Moreuil Wood. However it was not until the German Army had been forced to retreat in the Hundred Days Offensive of 1918, that limited numbers of cavalry were again able to operate with any effectiveness in their intended role. There was a successful charge by the British 7th Dragoon Guards on the last day of the war.[133]

In the wider spaces of the Eastern Front, a more fluid form of warfare continued and there was still a use for mounted troops. Some wide-ranging actions were fought, again mostly in the early months of the war.[134] However, even here the value of cavalry was overrated and the maintenance of large mounted formations at the front by the Russian Army put a major strain on the railway system, to little strategic advantage.[135] In February 1917, the Russian regular cavalry (exclusive of Cossacks) was reduced by nearly a third from its peak number of 200,000, as two squadrons of each regiment were dismounted and incorporated into additional infantry battalions.[136] Their Austro-Hungarian opponents, plagued by a shortage of trained infantry, had been obliged to progressively convert most horse cavalry regiments to dismounted rifle units starting in late 1914.[137]

Middle East

[edit]In the Middle East, during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign mounted forces (British, Indian, Ottoman, Australian, Arab and New Zealand) retained an important strategic role both as mounted infantry and cavalry.

In Egypt, the mounted infantry formations like the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade and Australian Light Horse of ANZAC Mounted Division, operating as mounted infantry, drove German and Ottoman forces back from Romani to Magdhaba and Rafa and out of the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula in 1916.

After a stalemate on the Gaza–Beersheba line between March and October 1917, Beersheba was captured by the Australian Mounted Division's 4th Light Horse Brigade. Their mounted charge succeeded after a coordinated attack by the British Infantry and Yeomanry cavalry and the Australian and New Zealand Light Horse and Mounted Rifles brigades. A series of coordinated attacks by these Egyptian Expeditionary Force infantry and mounted troops were also successful at the Battle of Mughar Ridge, during which the British infantry divisions and the Desert Mounted Corps drove two Ottoman armies back to the Jaffa—Jerusalem line. The infantry with mainly dismounted cavalry and mounted infantry fought in the Judean Hills to eventually almost encircle Jerusalem which was occupied shortly after.

During a pause in operations necessitated by the German spring offensive in 1918 on the Western Front, joint infantry and mounted infantry attacks towards Amman and Es Salt resulted in retreats back to the Jordan Valley which continued to be occupied by mounted divisions during the summer of 1918.

The Australian Mounted Division was armed with swords and in September, after the successful breaching of the Ottoman line on the Mediterranean coast by the British Empire infantry XXI Corps was followed by cavalry attacks by the 4th Cavalry Division, 5th Cavalry Division and Australian Mounted Divisions which almost encircled two Ottoman armies in the Judean Hills forcing their retreat. Meanwhile, Chaytor's Force of infantry and mounted infantry in ANZAC Mounted Division held the Jordan Valley, covering the right flank to later advance eastwards to capture Es Salt and Amman and half of a third Ottoman army. A subsequent pursuit by the 4th Cavalry Division and the Australian Mounted Division followed by the 5th Cavalry Division to Damascus. Armoured cars and 5th Cavalry Division lancers were continuing the pursuit of Ottoman units north of Aleppo when the Armistice of Mudros was signed by the Ottoman Empire.[138]

Post–World War I

[edit]A combination of military conservatism in almost all armies and post-war financial constraints prevented the lessons of 1914–1918 being acted on immediately. There was a general reduction in the number of cavalry regiments in the British, French, Italian[139] and other Western armies but it was still argued with conviction (for example in the 1922 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica) that mounted troops had a major role to play in future warfare.[140] The 1920s saw an interim period during which cavalry remained as a conspicuous element of all major armies, though much less so than prior to 1914.

Cavalry was extensively used in the Russian Civil War and the Soviet-Polish War.[141] The last major cavalry battle was the Battle of Komarów in 1920, between Poland and the Russian Bolsheviks. Colonial warfare in Morocco, Syria, the Middle East and the North West Frontier of India provided some opportunities for mounted action against enemies lacking advanced weaponry.

The post-war German Army (Reichsheer) was permitted a large proportion of cavalry (18 regiments or 16.4% of total manpower) under the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles.[142]

The British Army mechanised all cavalry regiments between 1929 and 1941, redefining their role from horse to armoured vehicles to form the Royal Armoured Corps together with the Royal Tank Regiment. The U.S. Cavalry abandoned its sabres in 1934[143] and commenced the conversion of its horsed regiments to mechanised units, starting with the First Regiment of Cavalry in January 1933.[144]

During the Turkish War of Independence, Turkish cavalry under General Fahrettin Altay was instrumental in the Kemalist victory over the invading Greek Army in 1922 during the Battle of Dumlupınar. The 5th Cavalry Corps was able to slip behind the main Greek army, cutting off all communication and supply lines as well as retreat options. This forced the surrender of the remaining Greek forces and may have been the last time in history that cavalry played a definitive role in the outcome of a battle.

During the 1930s, the French Army experimented with integrating mounted and mechanised cavalry units into larger formations.[145] Dragoon regiments were converted to motorised infantry (trucks and motor cycles), and cuirassiers to armoured units; while light cavalry (chasseurs a' cheval, hussars and spahis) remained as mounted sabre squadrons.[146] The theory was that mixed forces comprising these diverse units could utilise the strengths of each according to circumstances. In practice mounted troops proved unable to keep up with fast moving mechanised units over any distance.

The 39 cavalry regiments of the British Indian Army were reduced to 21 as the result of a series of amalgamations immediately following World War I. The new establishment remained unchanged until 1936 when three regiments were redesignated as permanent training units, each with six, still mounted, regiments linked to them. In 1938, the process of mechanization began with the conversion of a full cavalry brigade (two Indian regiments and one British) to armoured car and tank units. By the end of 1940, all of the Indian cavalry had been mechanized, initially and in the majority of cases, to motorized infantry transported in 15cwt trucks.[147] The last horsed regiment of the British Indian Army (other than the Viceroy's Bodyguard and some Indian States Forces regiments) was the 19th King George's Own Lancers which had its final mounted parade at Rawalpindi on 28 October 1939. This unit still exists in the Pakistan Army as an armored regiment.

World War II

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

While most armies still maintained cavalry units at the outbreak of World War II in 1939, significant mounted action was largely restricted to the Polish, Balkan, and Soviet campaigns. Rather than charge their mounts into battle, cavalry units were either used as mounted infantry (using horses to move into position and then dismounting for combat) or as reconnaissance units (especially in areas not suited to tracked or wheeled vehicles).

Polish

[edit]

A popular myth is that Polish cavalry armed with lances charged German tanks during the September 1939 campaign. This arose from misreporting of a single clash on 1 September near Krojanty, when two squadrons of the Polish 18th Lancers armed with sabres scattered German infantry before being caught in the open by German armoured cars.[148] Two examples illustrate how the myth developed. First, because motorised vehicles were in short supply, the Poles used horses to pull anti-tank weapons into position.[149] Second, there were a few incidents when Polish cavalry was trapped by German tanks, and attempted to fight free. However, this did not mean that the Polish army chose to attack tanks with horse cavalry.[150] Later, on the Eastern Front, the Red Army did deploy cavalry units effectively against the Germans.[151]

A more correct term would be "mounted infantry" instead of "cavalry", as horses were primarily used as a means of transportation, for which they were very suitable in view of the very poor road conditions in pre-war Poland. Another myth describes Polish cavalry as being armed with both sabres and lances; lances were used for peacetime ceremonial purposes only and the primary weapon of the Polish cavalryman in 1939 was a rifle. Individual equipment did include a sabre, probably because of well-established tradition, and in the case of a melee combat this secondary weapon would probably be more effective than a rifle and bayonet. Moreover, the Polish cavalry brigade order of battle in 1939 included, apart from the mounted soldiers themselves, light and heavy machine guns (wheeled), the Anti-tank rifle, model 35, anti-aircraft weapons, anti tank artillery such as the Bofors 37 mm, also light and scout tanks, etc. The last cavalry vs. cavalry mutual charge in Europe took place in Poland during the Battle of Krasnobród, when Polish and German cavalry units clashed with each other.

The last classical cavalry charge of the war took place on March 1, 1945, during the Battle of Schoenfeld by the 1st "Warsaw" Independent Cavalry Brigade. Infantry and tanks had been employed to little effect against the German position, both of which floundered in the open wetlands only to be dominated by infantry and antitank fire from the German fortifications on the forward slope of Hill 157, overlooking the wetlands. The Germans had not taken cavalry into consideration when fortifying their position which, combined with the "Warsaw"s swift assault, overran the German anti-tank guns and consolidated into an attack into the village itself, now supported by infantry and tanks.

Greek

[edit]The Italian invasion of Greece in October 1940 saw mounted cavalry used effectively by the Greek defenders along the mountainous frontier with Albania. Three Greek cavalry regiments (two mounted and one partially mechanized) played an important role in the Italian defeat in this difficult terrain.[152]

Soviet

[edit]The contribution of Soviet cavalry to the development of modern military operational doctrine and its importance in defeating Nazi Germany has been eclipsed by the higher profile of tanks and airplanes.[153] Soviet cavalry contributed significantly to the defeat of the Axis armies.[153] They were able to provide the most mobile troops available in the early stages, when trucks and other equipment were low in quality; as well as providing cover for retreating forces.

Considering their relatively limited numbers, the Soviet cavalry played a significant role in giving Germany its first real defeats in the early stages of the war. The continuing potential of mounted troops was demonstrated during the Battle of Moscow, against Guderian and the powerful central German 9th Army. Pavel Belov was given by Stavka a mobile group including the elite 9th tank brigade, ski battalions, Katyusha rocket launcher battalion among others, the unit additionally received new weapons. This newly created group became the first to carry the Soviet counter-offensive in late November, when the general offensive began on 5 December. These mobile units often played major roles in both defensive and offensive operations.

Cavalry were amongst the first Soviet units to complete the encirclement in the Battle of Stalingrad, thus sealing the fate of the German 6th Army. Mounted Soviet forces also played a role in the encirclement of Berlin, with some Cossack cavalry units reaching the Reichstag in April 1945. Throughout the war they performed important tasks such as the capture of bridgeheads which is considered one of the hardest jobs in battle, often doing so with inferior numbers. For instance the 8th Guards Cavalry Regiment of the 2nd Guards Cavalry Division (Soviet Union), 1st Guards Cavalry Corps often fought outnumbered against elite German units.

By the final stages of the war only the Soviet Union was still fielding mounted units in substantial numbers, some in combined mechanized and horse units. The main advantage of this tactical approach was in enabling mounted infantry to keep pace with advancing tanks. Other factors favoring the retention of mounted forces included the high quality of Russian Cossacks, which provided about half of all mounted Soviet cavalry throughout the war. They excelled in warfare manoeuvers, since the lack of roads limited the effectiveness of wheeled vehicles in many parts of the Eastern Front. Another consideration was that sufficient logistic capacity was often not available to support very large motorized forces, whereas cavalry was relatively easy to maintain when detached from the main army and acting on its own initiative. The main usage of the Soviet cavalry involved infiltration through front lines with subsequent deep raids, which disorganized German supply lines. Another role was the pursuit of retreating enemy forces during major front-line operations and breakthroughs.

In the occupied territory of the USSR, Soviet partisans effectively used cavalry not only as individual horsemen (as messengers and scouts), but also in combat (as a mobile reserve). An example of the effective use of cavalry is the battle for the settlement Golynki in 1943. A Nazi police punitive detachment that arrived in the village to forcibly evict the residents was attacked here by a combat group under the command of A. Sobolev from the "Fighters" partisan detachment and began to retreat. The cavalry detachment under the command of P. P. Vershigora, which arrived at the scene of the battle, suddenly attacked them from the flank - as a result, enemy squad was destroyed. The infantrymen running across the field had little chance of escaping from the partisan cavalry[154].

Hungarian

[edit]In April 1941, Hungarian troops (including cavalry units) participated in the invasion of Yugoslavia. Later, Hungarian cavalry units were used for patrolling the area, fighting partisans, and performing police functions in the occupied territory of Yugoslavia[155].

During the war against the USSR, the Royal Hungarian Army's hussars were typically only used to undertake reconnaissance tasks against Soviet forces, and then only in detachments of section or squadron strength.

The last documented hussar attack was conducted by Lieutenant Colonel Kálmán Mikecz on August 16, 1941, at Nikolaev. The hussars arriving as reinforcements, were employed to break through Russian positions ahead of German troops. The hussars equipped with swords and submachine guns broke through the Russian lines in a single attack.

An eyewitness account of the last hussar attack by Erich Kern, a German officer, was written in his memoir in 1948:[156]

… We were again in a tough fight with the desperately defensive enemy who dug himself along a high railway embankment. We've been attacked four times already, and we've been kicked back all four times. The battalion commander swore, but the company commanders were helpless. Then, instead of the artillery support we asked for countless times, a Hungarian hussar regiment appeared on the scene. We laughed. What the hell do they want here with their graceful, elegant horses? We froze at once: these Hungarians went crazy. Cavalry Squadron approached after a cavalry squadron. The command word rang. The bronze-brown, slender riders almost grew to their saddle. Their shining colonel of golden parolis jerked his sword. Four or five armored cars cut out of the wings, and the regiment slashed across the wide plain with flashing swords in the afternoon sun. Seydlitz attacked like this once before. Forgetting all caution, we climbed out of our covers. It was all like a great equestrian movie. The first shots rumbled, then became less frequent. With astonished eyes, in disbelief, we watched as the Soviet regiment, which had so far repulsed our attacks with desperate determination, now turned around and left its positions in panic. And the triumphant Hungarians chased the Russian in front of them and shredded them with their glittering sabers. The hussar sword, it seems, was a bit much for the nerves of Russians. Now, for once, the ancient weapon has triumphed over modern equipment ....

Italian

[edit]The last mounted sabre charge by Italian cavalry occurred on August 24, 1942, at Isbuscenski (Russia), when a squadron of the Savoia Cavalry Regiment charged the 812th Siberian Infantry Regiment. The remainder of the regiment, together with the Novara Lancers made a dismounted attack in an action that ended with the retreat of the Russians after heavy losses on both sides.[157] The final Italian cavalry action occurred on October 17, 1942, in Poloj (now Croatia) by a squadron of the Alexandria Cavalry Regiment against a large group of Yugoslav partisans.

Other Axis Powers

[edit]Romanian, Hungarian and Italian cavalry were dispersed or disbanded following the retreat of the Axis forces from Russia.[158] Germany still maintained some mounted (mixed with bicycles) SS and Cossack units until the last days of the War.

Finnish

[edit]Finland used mounted troops against Russian forces effectively in forested terrain during the Continuation War.[159] The last Finnish cavalry unit was not disbanded until 1947.

American

[edit]The U.S. Army's last horse cavalry actions were fought during World War II: a) by the 26th Cavalry Regiment—a small mounted regiment of Philippine Scouts which fought the Japanese during the retreat down the Bataan peninsula, until it was effectively destroyed by January 1942; and b) on captured German horses by the mounted reconnaissance section of the U.S. 10th Mountain Division in a spearhead pursuit of the German Army across the Po Valley in Italy in April 1945.[160] The last horsed U.S. Cavalry (the Second Cavalry Division) were dismounted in March 1944.

British

[edit]All British Army cavalry regiments had been mechanised since 1 March 1942 when the Queen's Own Yorkshire Dragoons (Yeomanry) was converted to a motorised role, following mounted service against the Vichy French in Syria the previous year. The final cavalry charge by British Empire forces occurred on 21 March 1942 when a 60 strong patrol of the Burma Frontier Force encountered Japanese infantry near Toungoo airfield in central Myanmar. The Sikh sowars of the Frontier Force cavalry, led by Captain Arthur Sandeman of The Central India Horse (21st King George V's Own Horse), charged in the old style with sabres and most were killed.

Mongolian

[edit]

In the early stages of World War II, mounted units of the Mongolian People's Army were involved in the Battle of Khalkhin Gol against invading Japanese forces. Soviet forces under the command of Georgy Zhukov, together with Mongolian forces, defeated the Japanese Sixth army and effectively ended the Soviet–Japanese Border Wars. After the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact of 1941, Mongolia remained neutral throughout most of the war, but its geographical situation meant that the country served as a buffer between Japanese forces and the Soviet Union. In addition to keeping around 10% of the population under arms, Mongolia provided half a million trained horses for use by the Soviet Army. In 1945 a partially mounted Soviet-Mongolian Cavalry Mechanized Group played a supporting role on the western flank of the Soviet invasion of Manchuria. The last active service seen by cavalry units of the Mongolian Army occurred in 1946–1948, during border clashes between Mongolia and the Republic of China.

Post–World War II to the present day

[edit]

While most modern "cavalry" units have some historic connection with formerly mounted troops this is not always the case. The modern Irish Defence Forces (DF) includes a "Cavalry Corps" equipped with armoured cars and Scorpion tracked combat reconnaissance vehicles. The DF has never included horse cavalry since its establishment in 1922 (other than a small mounted escort of Blue Hussars drawn from the Artillery Corps when required for ceremonial occasions). However, the mystique of the cavalry is such that the name has been introduced for what was always a mechanised force.

Some engagements in late 20th and early 21st century guerrilla wars involved mounted troops, particularly against partisan or guerrilla fighters in areas with poor transport infrastructure. Such units were not used as cavalry but rather as mounted infantry. Examples occurred in Afghanistan, Portuguese Africa and Rhodesia. The French Army used existing mounted squadrons of Spahis to a limited extent for patrol work during the Algerian War (1954–1962). The last mounted charge by French cavalry was carried out on 14 May 1957 by a detachment of Spahis at Magoura during the Algerian War.[161]

The Swiss Army maintained a mounted dragoon regiment for combat purposes until 1973. The Portuguese Army used horse mounted cavalry with some success in the wars of independence in Angola and Mozambique in the 1960s and 1970s.[162] During the 1964–1979 Rhodesian Bush War the Rhodesian Army created an elite mounted infantry unit called Grey's Scouts to patrol the country's borders and fight nationalist guerrilla units. It was retained for several years into the 1980s following Rhodesia's transition to become Zimbabwe. In the 1978 to present Afghan Civil War period there have been several instances of horse mounted combat.