Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Winterland Ballroom

View on WikipediaWinterland, called at first New Dreamland Auditorium and later Winterland Arena and Winterland Ballroom, was an ice-skating rink and music venue in San Francisco operational from 1928 to 1979 and demolished in 1986.

Key Information

Built at the corner of Post Street and Steiner Street, it was converted for exclusive use for music in 1971 by concert promoter Bill Graham, who made it a popular stop for rock acts. Graham's related merchandising company Winterland Productions sold concert shirts, memorabilia and sports-team merchandise.

History

[edit]New Dreamland Auditorium opened on June 29, 1928,[2] as a skating rink that could convert into a seated entertainment venue. The building cost $1 million, equivalent to $18.8 million in 2025.[3] The name change to Winterland came in the late 1930s; the building successfully operated through the Great Depression.

The New Dreamland was built on the site of the Dreamland Rink (midway on the west side of Steiner between Post and Sutter) and Sid Grauman's National Theatre (on the corner of Post and Steiner).[4]

In 1936, Winterland began hosting the Shipstads and Johnson Ice Follies.[5] Impresario Clifford C. Fischer staged an authorized production of the Folies Bergère, the Folies Bergère of 1944, at the Winterland Ballroom in November 1944.[6] The Ballroom hosted opera, boxing and tennis matches.[7]

As a music venue

[edit]Starting on September 23, 1966, with a double bill of Jefferson Airplane and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Bill Graham began to occasionally rent the venue, which had an audience capacity of 5,400, for larger concerts that his nearby Fillmore Auditorium could not properly accommodate. After closing the Fillmore West in 1971, he began to hold regular weekend shows at Winterland.

Various popular rock acts played there, including such bands and musicians as Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Bruce Springsteen, the Rolling Stones, the J. Geils Band, the Who, Black Sabbath, James Gang, Kansas, Mahogany Rush, Quicksilver Messenger Service, UFO, REO Speedwagon, Queen, Slade, Boston, Cream, Yes, Fleetwood Mac, Kiss, the Doors, Jimi Hendrix, Steppenwolf, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Marshall Tucker Band, Outlaws, Charlie Daniels, Styx, Van Morrison, the Allman Brothers Band, Grateful Dead, the Band, Big Brother and the Holding Company (with Janis Joplin), Dan Hicks and His Hot Licks, Neil Young, Jethro Tull, Pink Floyd, Ten Years After, Wishbone Ash, Rush, Electric Light Orchestra, David Bowie, Genesis, Santana, Jefferson Airplane, Sons of Champlin, Sex Pistols, Traffic, Golden Earring, Grand Funk Railroad, Humble Pie, Bob Seger and the Silver Bullet Band, Robin Trower, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Sha Na Na, Loggins and Messina, Lee Michaels, Heart, Journey, Deep Purple, J.J. Cale, Spirit, the Chambers Brothers, Alice Cooper, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, Foghat, Mountain, B.B. King, Montrose, George Thorogood and the Delaware Destroyers and Elvis Costello. Led Zeppelin first performed their song "Whole Lotta Love" there.

The Tubes headlined New Year's Eve 1975 with Flo and Eddie.

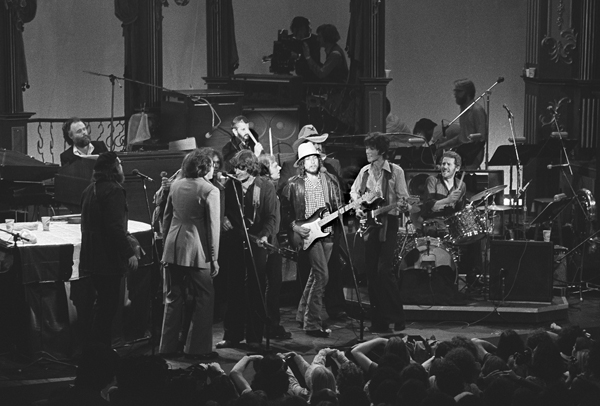

Many of the best-known rock acts from the 1960s and 1970s played at Winterland or played two blocks away across Geary Boulevard at the original Fillmore Auditorium. Peter Frampton recorded parts of the fourth-best-selling live album ever, Frampton Comes Alive!, at Winterland. The Grateful Dead made Winterland their home base, and The Band played their last show there on Thanksgiving Day 1976. That concert, featuring numerous guest performers including Neil Young, Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, and many others, was filmed by Martin Scorsese and released in theaters and as a soundtrack under the name The Last Waltz. Winterland also hosted the Sex Pistols' final show, on January 14, 1978.[8]

Final concerts

[edit]During Winterland's final month of existence, shows were booked nearly every night. Acts included the Sex Pistols, the Tubes,[9] the Ramones, Smokey Robinson, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, and on December 15–16, 1978, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. Springsteen's December 15 show was broadcast on local radio station KSAN-FM.

Winterland closed on New Year's Eve 1978 / New Year's Day 1979 with a concert by the Grateful Dead, New Riders of the Purple Sage, and the Blues Brothers. The show lasted over eight hours, with the Grateful Dead's performance — documented on DVD and CD as The Closing of Winterland — lasting nearly six hours, beginning at midnight with Bill Graham's favorite Dead song, "Sugar Magnolia". After the show, the crowd was treated to a hot, buffet-style champagne breakfast. The final show was simulcast live on radio station KSAN-FM and the local PBS TV station KQED.[10]

Winterland was eventually razed in 1985 and replaced by apartments.[11]

Live recordings at Winterland

[edit]A number of films and recordings were made in whole or in part at the Winterland Arena.[12]

Concert films

[edit]- The Band – The Last Waltz

- Grateful Dead – The Grateful Dead Movie, The Closing of Winterland

- Sha Na Na – Live at Winterland (1974) (bootleg)

- Kiss – Kissology Volume One: 1974–1977

- Sex Pistols – The Filth and the Fury

Live albums

[edit]- Avengers – Live at Winterland 1978

- The Allman Brothers Band – Wipe the Windows, Check the Oil, Dollar Gas

- Big Brother and the Holding Company (lead singer Janis Joplin) – Live at Winterland '68

- The Blues Brothers – Live – The Closing of Winterland, 31st December 1978

- Cream – Wheels of Fire (erroneously listed as being recorded at the Fillmore on the original LP), Live Cream, Live Cream Volume II, Those Were the Days

- Electric Light Orchestra – Live at Winterland '76

- Virgil Fox - Heavy Organ: Bach Live in San Francisco, Winterland

- Peter Frampton – Frampton Comes Alive!

- Grateful Dead – Steal Your Face, Dick's Picks Volume 10, So Many Roads (1965–1995), The Closing of Winterland, The Grateful Dead Movie Soundtrack, Winterland 1973: The Complete Recordings, Road Trips Volume 1 Number 4, Winterland June 1977: The Complete Recordings, Dave's Picks Volume 13, Dave's Picks Volume 42

- Jimi Hendrix – Live at Winterland, The Jimi Hendrix Concerts (live tracks of various gigs), and Winterland (4-CD box set)

- The Doors – Boot Yer Butt: The Doors Bootlegs

- Jefferson Airplane – Thirty Seconds Over Winterland

- Loggins and Messina – On Stage

- Sammy Hagar – All Night Long

- Bruce Springsteen – Live/1975–85. Both December 1978 concerts were released in full as part of his archive series on December 20, 2019.

- The Band – The Last Waltz

- Humble Pie – Live at Winterland

- Paul Butterfield's Better Days – Live at Winterland Ballroom (1973)

- Sha Na Na – The Golden Age of Rock 'n' Roll

- Sutherland Brothers & Quiver – Winterland

Further reading

[edit]- Tillmany, Jack (31 August 2005). Theatres of San Francisco. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781439630945 – via Google Books.

- "Winterland Stories - The Shows". Thrasherswheat.org.

- "Winterland Stories Photos". Thrasherswheat.org.

- "Ice Follies Return To S.F." Sausalito News. 16 May 1940. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Nolte, Carl (4 May 2008). "S.F. business leader George C. Fleharty dies". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- "Winterland, Post and Steiner, San Francisco, CA". Jerry's Brokendown Palaces. 1 February 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- "Summers of Ice Skating". Moretosayfromsf.com. 14 May 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- "San Francisco Org Planning West's Top Indoor Show Palace" (PDF). The Billboard. February 9, 1946. p. 43. Retrieved 21 February 2019 – via AmericanRadioHistory.com.

- "Harlick Skating Boots : Photo Galleries : Historical Ice Skating Photo Galleries". Harlick.com.

- "Poster, card, and photo from The Folies Bergere of 1944 in San Francisco". Glopad.org. Retrieved 2014-06-09.

- "Folies Bergere of 1944 Opens Soon at Winterland". Berkeley Daily Gazette. November 23, 1943. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- "Folies Bergère 1939". PlaybillVault.com. Archived from the original on 2014-12-25. Retrieved 2014-06-09.

References

[edit]- ^ "Winterland Stories Photos #2". Thrasherswheat.org.

- ^ "2–0 Police Journal". MyHeritage. San Francisco, CA. November 1928. pp. 20–21, 88–89. Retrieved 2016-01-15.

Compilation of Published Sources

- ^ Counter, Bill (2020-01-29). "Dreamland / Winterland". San Francisco Theatres.

- ^ Counter, Bill (2017-08-27). "The National Theatre". San Francisco Theatres.

- ^ Ganahl, Jane (24 August 1998). "Eddie Shipstad, Ice Follies man and philanthropist". The San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ "Follies Bergere in San Francisco, 1944". 1943-11-23. Retrieved 2014-06-09.

- ^ "Photo of Winterland with boxing ring". Skelton Studios. November 8, 1950. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2019 – via San Francisco Public Library.

- ^ Fricke, David (November 2001). The Last Waltz (liner notes). Warner Bros. pp. 25–27. Retrieved 2019-07-07.

- ^ "Concert Vault". Concert Vault. Archived from the original on 2009-09-07. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ^ Selvin, Joel (October 23, 2003). "It was 1978, the night they closed old Winterland down — and the Grateful Dead's all-night show lives on in memories, flashbacks — and now a DVD". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ Hartlaub, Peter (January 25, 2018). "Rare photos of the demolition of Winterland Ballroom". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ Prior, Ginny (18 November 2010). "Collection tells story of legendary local rink". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 21 February 2019.