Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Write amplification

View on WikipediaThis article needs to be updated. (July 2020) |

Write amplification (WA) is an undesirable phenomenon associated with flash memory and solid-state drives (SSDs) where the actual amount of information physically written to the storage media is a multiple of the logical amount intended to be written.

Because flash memory must be erased before it can be rewritten, with much coarser granularity of the erase operation when compared to the write operation,[a] the process to perform these operations results in moving (or rewriting) user data and metadata more than once. Thus, rewriting some data requires an already-used-portion of flash to be read, updated, and written to a new location, together with initially erasing the new location if it was previously used. Due to the way flash works, much larger portions of flash must be erased and rewritten than actually required by the amount of new data. This multiplying effect increases the number of writes required over the life of the SSD, which shortens the time it can operate reliably. The increased writes also consume bandwidth to the flash memory, which reduces write performance to the SSD.[1][3] Many factors will affect the WA of an SSD; some can be controlled by the user and some are a direct result of the data written to and usage of the SSD.

Intel and SiliconSystems (acquired by Western Digital in 2009) used the term write amplification in their papers and publications in 2008.[4] WA is typically measured by the ratio of writes committed to the flash memory to the writes coming from the host system. Without compression, WA cannot drop below one. Using compression, SandForce has claimed to achieve a write amplification of 0.5,[5] with best-case values as low as 0.14 in the SF-2281 controller.[6]

Basic SSD operation

[edit]

Due to the nature of flash memory's operation, data cannot be directly overwritten as it can in a hard disk drive. When data is first written to an SSD, the cells all start in an erased state so data can be written directly using pages at a time (often 4–8 kilobytes (KB)[update] in size). The SSD controller on the SSD, which manages the flash memory and interfaces with the host system, uses a logical-to-physical mapping system known as logical block addressing (LBA) that is part of the flash translation layer (FTL).[7] When new data comes in replacing older data already written, the SSD controller will write the new data in a new location and update the logical mapping to point to the new physical location. The data in the former location is no longer valid, and will need to be erased before that location can be written to again.[1][8]

Flash memory can be programmed and erased only a limited number of times. This is often referred to as the maximum number of program/erase cycles (P/E cycles) it can sustain over the life of the flash memory. Single-level cell (SLC) flash, designed for higher performance and longer endurance, can typically operate between 50,000 and 100,000 cycles. As of 2011[update], multi-level cell (MLC) flash is designed for lower cost applications and has a greatly reduced cycle count of typically between 3,000 and 5,000. Since 2013, triple-level cell (TLC) (e.g., 3D NAND) flash has been available, with cycle counts dropping to 1,000 program-erase (P/E) cycles. A lower write amplification is more desirable, as it corresponds to a reduced number of P/E cycles on the flash memory and thereby to an increased SSD life.[1] The wear of flash memory may also cause performance degrade, such as I/O speed degrade.

Calculating the value

[edit]Write amplification was always present in SSDs before the term was defined, but it was in 2008 that both Intel[4][9] and SiliconSystems started using the term in their papers and publications.[10] All SSDs have a write amplification value and it is based on both what is currently being written and what was previously written to the SSD. In order to accurately measure the value for a specific SSD, the selected test should be run for enough time to ensure the drive has reached a steady state condition.[3]

A simple formula to calculate the write amplification of an SSD is:[1][11][12]

The two quantities used for calculation can be obtained via SMART statistics (ATA F7/F8;[13] ATA F1/F9).

Factors affecting the value

[edit]Many factors affect the write amplification of an SSD. The table below lists the primary factors and how they affect the write amplification. For factors that are variable, the table notes if it has a direct relationship or an inverse relationship. For example, as the amount of over-provisioning increases, the write amplification decreases (inverse relationship). If the factor is a toggle (enabled or disabled) function then it has either a positive or negative relationship.[1][7][14]

| Factor | Description | Type | Relationship* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Garbage collection | The efficiency of the algorithm used to pick the next best block to erase and rewrite | Variable | Inverse (good) |

| Over-provisioning | The percentage of over-provisioning capacity which is allocated to the SSD controller | Variable | Inverse (good) |

| Device's built-in DRAM buffer | The built-in DRAM buffer of the storage device (usually SSD) may used to decrease the write amplification | Variable | Inverse (good) |

| TRIM command for SATA or UNMAP for SCSI | These commands must be sent by the operating system (OS) which tells the storage device which pages contain invalid data. SSDs receiving these commands can then reclaim the blocks containing these pages as free space when they are erased instead of copying the invalid data to clean pages. | Toggle | Positive (good) |

| Zoned Storage | Zoned Storage is a storage technology set that can reduces write amplification and product cost. It divides the storage device to many zones (usually the blocks of flash memory), and allows operating systems (OS) to write data sequently on zones. It needs both operating system and device (such as SSD) to support this feature. Also it can improve read performance as it can reduce read disturb. | Toggle | Positive (good) |

| Free user space | The percentage of the user capacity free of actual user data; requires TRIM, otherwise the SSD gains no benefit from any free user capacity | Variable | Inverse (good) |

| Secure erase | Erases all user data and related metadata which resets the SSD to the initial out-of-box performance (until garbage collection resumes) | Toggle | Positive (good) |

| Wear leveling | The efficiency of the algorithm that ensures every block is written an equal number of times to all other blocks as evenly as possible | Variable | Depends |

| Separating static and dynamic data | Grouping data based on how often it tends to change | Toggle | Positive (good) |

| Sequential writes | In theory, sequential writes have less write amplification, but other factors will still affect the real situation | Toggle | Positive (good) |

| Random writes | Writing non-sequential data and smaller data sizes will have greater impact on write amplification | Toggle | Negative (bad) |

| Data compression which includes data deduplication | Write amplification goes down and SSD speed goes up when data compression and deduplication eliminates more redundant data. | Variable | Inverse (good) |

| Using Multi-level cell (including TLC/QLC and onward) NAND in SLC mode | This writes data at a rate of one bit per cell instead of the designed number of bits per cell (normally two bits per cell or three bits per cell) to speed up reads and writes. If capacity limits of the NAND in SLC mode are approached, the SSD must rewrite the oldest data written in SLC mode into MLC / TLC mode to allow space in the SLC mode NAND to be erased in order to accept more data. However, this approach can reduce wear by keeping frequently-changed pages in SLC mode to avoid programming these changes in MLC / TLC mode, because writing in MLC / TLC mode does more damage to the flash than writing in SLC mode.[citation needed] Therefore, this approach drives up write amplification but could reduce wear when writing patterns target frequently-written pages. However, sequential- and random-write patterns will aggravate the damage because there are no or few frequently-written pages that could be contained in the SLC area, forcing old data to need to be constantly be rewritten to MLC / TLC from the SLC area. This method is sometimes called "SLC cache" or "SLC buffer". It has two types of "SLC buffer"; one type is static SLC buffer (a SLC buffer based on the over-provisioning area), another type is dynamic SLC buffer (dynamically change its size on factors such as free user capacity). However the SLC buffer usually does not accelerate read speed. | Toggle | Depends |

| Type | Relationship modified | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Direct | As the factor increases the WA increases |

| Inverse | As the factor increases the WA decreases | |

| Depends | Depends on different manufacturers and models | |

| Toggle | Positive | When the factor is present the WA decreases |

| Negative | When the factor is present the WA increases | |

| Depends | Depends on different manufacturers and models |

Garbage collection

[edit]

Data is written to the flash memory in units called pages (made up of multiple cells). However, the memory can only be erased in larger units called blocks (made up of multiple pages).[2] If the data in some of the pages of the block are no longer needed (also called stale pages), only the pages with good data in that block are read and rewritten into another previously erased empty block.[3] Then the free pages left by not moving the stale data are available for new data. This is a process called garbage collection (GC).[1][11] All SSDs include some level of garbage collection, but they may differ in when and how fast they perform the process.[11] Garbage collection is a big part of write amplification on the SSD.[1][11]

Reads do not require an erase of the flash memory, so they are not generally associated with write amplification. In the limited chance of a read disturb error, the data in that block is read and rewritten, but this would not have any material impact on the write amplification of the drive.[15]

Background garbage collection

[edit]The process of garbage collection involves reading and rewriting data to the flash memory. This means that a new write from the host will first require a read of the whole block, a write of the parts of the block which still include valid data, and then a write of the new data. This can significantly reduce the performance of the system.[16] Many SSD controllers implement background garbage collection (BGC), sometimes called idle garbage collection or idle-time garbage collection (ITGC), where the controller uses idle time to consolidate blocks of flash memory before the host needs to write new data. This enables the performance of the device to remain high.[17]

If the controller were to background garbage collect all of the spare blocks before it was absolutely necessary, new data written from the host could be written without having to move any data in advance, letting the performance operate at its peak speed. The trade-off is that some of those blocks of data are actually not needed by the host and will eventually be deleted, but the OS did not tell the controller this information (until TRIM was introduced). The result is that the soon-to-be-deleted data is rewritten to another location in the flash memory, increasing the write amplification. In some of the SSDs from OCZ the background garbage collection clears up only a small number of blocks then stops, thereby limiting the amount of excessive writes.[11] Another solution is to have an efficient garbage collection system which can perform the necessary moves in parallel with the host writes. This solution is more effective in high write environments where the SSD is rarely idle.[18] The SandForce SSD controllers[16] and the systems from Violin Memory have this capability.[14]

Filesystem-aware garbage collection

[edit]In 2010, some manufacturers (notably Samsung) introduced SSD controllers that extended the concept of BGC to analyze the file system used on the SSD, to identify recently deleted files and unpartitioned space. Samsung claimed that this would ensure that even systems (operating systems and SATA controller hardware) which do not support TRIM could achieve similar performance. The operation of the Samsung implementation appeared to assume and require an NTFS file system.[19] It is not clear if this feature is still available in currently shipping SSDs from these manufacturers. Systemic data corruption has been reported on these drives if they are not formatted properly using MBR and NTFS.[citation needed]

TRIM

[edit]TRIM is a SATA command that enables the operating system to tell an SSD which blocks of previously saved data are no longer needed as a result of file deletions or volume formatting. When an LBA is replaced by the OS, as with an overwrite of a file, the SSD knows that the original LBA can be marked as stale or invalid and it will not save those blocks during garbage collection. If the user or operating system erases a file (not just remove parts of it), the file will typically be marked for deletion, but the actual contents on the disk are never actually erased. Because of this, the SSD does not know that it can erase the LBAs previously occupied by the file, so the SSD will keep including such LBAs in the garbage collection.[20][21][22]

The introduction of the TRIM command resolves this problem for operating systems that support it like Windows 7,[21] Mac OS (latest releases of Snow Leopard, Lion, and Mountain Lion, patched in some cases),[23] FreeBSD since version 8.1,[24] and Linux since version 2.6.33 of the Linux kernel mainline.[25] When a file is permanently deleted or the drive is formatted, the OS sends the TRIM command along with the LBAs that no longer contain valid data. This informs the SSD that the LBAs in use can be erased and reused. This reduces the LBAs needing to be moved during garbage collection. The result is the SSD will have more free space enabling lower write amplification and higher performance.[20][21][22]

Limitations and dependencies

[edit]The TRIM command also needs the support of the SSD. If the firmware in the SSD does not have support for the TRIM command, the LBAs received with the TRIM command will not be marked as invalid and the drive will continue to garbage collect the data assuming it is still valid. Only when the OS saves new data into those LBAs will the SSD know to mark the original LBA as invalid.[22] SSD Manufacturers that did not originally build TRIM support into their drives can either offer a firmware upgrade to the user, or provide a separate utility that extracts the information on the invalid data from the OS and separately TRIMs the SSD. The benefit would be realized only after each run of that utility by the user. The user could set up that utility to run periodically in the background as an automatically scheduled task.[16]

Just because an SSD supports the TRIM command does not necessarily mean it will be able to perform at top speed immediately after a TRIM command. The space which is freed up after the TRIM command may be at random locations spread throughout the SSD. It will take a number of passes of writing data and garbage collecting before those spaces are consolidated to show improved performance.[22]

Even after the OS and SSD are configured to support the TRIM command, other conditions might prevent any benefit from TRIM. As of early 2010[update], databases and RAID systems are not yet TRIM-aware and consequently will not know how to pass that information on to the SSD. In those cases the SSD will continue to save and garbage collect those blocks until the OS uses those LBAs for new writes.[22]

The actual benefit of the TRIM command depends upon the free user space on the SSD. If the user capacity on the SSD was 100 GB and the user actually saved 95 GB of data to the drive, any TRIM operation would not add more than 5 GB of free space for garbage collection and wear leveling. In those situations, increasing the amount of over-provisioning by 5 GB would allow the SSD to have more consistent performance because it would always have the additional 5 GB of additional free space without having to wait for the TRIM command to come from the OS.[22]

Over-provisioning

[edit]

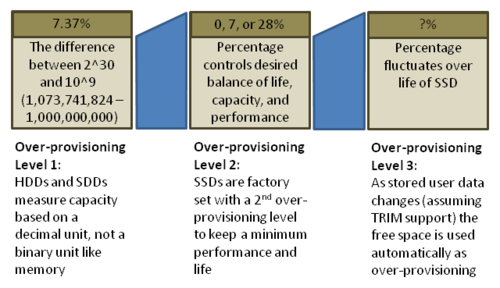

Over-provisioning (sometimes spelled as OP, over provisioning, or overprovisioning) is the difference between the physical capacity of the flash memory and the logical capacity presented through the operating system (OS) as available for the user. During the garbage collection, wear-leveling, and bad block mapping operations on the SSD, the additional space from over-provisioning helps lower the write amplification when the controller writes to the flash memory.[4][26][27] Over-provisioning region is also used for storing firmware data like FTL tables. Mid-end and high-end flash products are usually have bigger over-provisioning spaces. Over-provisioning is represented as a percentage ratio of extra capacity to user-available capacity:[28]

Over-provisioning typically comes from three sources:

- The computation of the capacity and use of gigabyte (GB) as the unit instead of gibibyte (GiB). Both HDD and SSD vendors use the term GB to represent a decimal GB or 1,000,000,000 (= 109) bytes. Like most other electronic storage, flash memory is assembled in powers of two, so calculating the physical capacity of an SSD would be based on 1,073,741,824 (= 230) per binary GB or GiB. The difference between these two values is 7.37% (= (230 − 109) / 109 × 100%). Therefore, a 128 GB SSD with 0% additional over-provisioning would provide 128,000,000,000 bytes to the user (out of 137,438,953,472 total). This initial 7.37% is typically not counted in the total over-provisioning number, and the true amount available is usually less as some storage space is needed for the controller to keep track of non-operating system data such as block status flags.[26][28] The 7.37% figure may extend to 9.95% in the terabyte range, as manufacturers take advantage of a further grade of binary/decimal unit divergence to offer 1 or 2 TB drives of 1000 and 2000 GB capacity (931 and 1862 GiB), respectively, instead of 1024 and 2048 GB (as 1 TB = 1,000,000,000,000 bytes in decimal terms, but 1,099,511,627,776 in binary).[citation needed]

- Manufacturer decision. This is done typically at 0%, 7%, 14% or 28%, based on the difference between the decimal gigabyte of the physical capacity and the decimal gigabyte of the available space to the user. This type of OP is usually called static OP. As an example, a manufacturer might publish a specification for their SSD at 100, 120 or 128 GB based on 128 GB of possible capacity. This difference is 28%, 14%, 7% and 0% respectively and is the basis for the manufacturer claiming they have 28% of over-provisioning on their drive. This does not count the additional 7.37% of capacity available from the difference between the decimal and binary gigabyte.[26][28]

- Known free user space on the drive, gaining endurance and performance at the expense of reporting unused portions, or at the expense of current or future capacity. This free space can be identified by the operating system using the TRIM command. This type of OP is usually called dynamic OP. Alternatively, some SSDs provide a utility that permits the end user to select additional over-provisioning. Furthermore, if any SSD is set up with an overall partitioning layout smaller than 100% of the available space, that unpartitioned space will be automatically used by the SSD as over-provisioning as well.[28] Yet another source of over-provisioning is operating system minimum free space limits; some operating systems maintain a certain minimum free space per drive, particularly on the boot or main drive. If this additional space can be identified by the SSD, perhaps through continuous usage of the TRIM command, then this acts as semi-permanent over-provisioning. Over-provisioning often takes away from user capacity, either temporarily or permanently, but it gives back reduced write amplification, increased endurance, and increased performance.[18][27][29][30][31]

Free user space

[edit]The SSD controller will use free blocks on the SSD for garbage collection and wear leveling. The portion of the user capacity which is free from user data (either already TRIMed or never written in the first place) will look the same as over-provisioning space (until the user saves new data to the SSD). If the user saves data consuming only half of the total user capacity of the drive, the other half of the user capacity will look like additional over-provisioning (as long as the TRIM command is supported in the system).[22][32]

DRAM buffer

[edit]The DRAM buffer (if present) on flash devices (usually SSD) can be used for caching FTL table, buffering data writes, and garbage collection.

Secure erase

[edit]The ATA Secure Erase command is designed to remove all user data from a drive. With an SSD without integrated encryption, this command will put the drive back to its original out-of-box state. This will initially restore its performance to the highest possible level and the best (lowest number) possible write amplification, but as soon as the drive starts garbage collecting again the performance and write amplification will start returning to the former levels.[33][34] Many tools use the ATA Secure Erase command to reset the drive and provide a user interface as well. One free tool that is commonly referenced in the industry is called HDDerase.[34][35] GParted and Ubuntu live CDs provide a bootable Linux system of disk utilities including secure erase.[36]

Drives which encrypt all writes on the fly can implement ATA Secure Erase in another way. They simply zeroize and generate a new random encryption key each time a secure erase is done. In this way the old data cannot be read any more, as it cannot be decrypted.[37] Some drives with an integrated encryption will physically clear all blocks after that as well, while other drives may require a TRIM command to be sent to the drive to put the drive back to its original out-of-box state (as otherwise their performance may not be maximized).[38]

Wear leveling

[edit]If a particular block was programmed and erased repeatedly without writing to any other blocks, that block would wear out before all the other blocks – thereby prematurely ending the life of the SSD. For this reason, SSD controllers use a technique called wear leveling to distribute writes as evenly as possible across all the flash blocks in the SSD.

In a perfect scenario, this would enable every block to be written to its maximum life so they all fail at the same time. Unfortunately, the process to evenly distribute writes requires data previously written and not changing (cold data) to be moved, so that data which are changing more frequently (hot data) can be written into those blocks. Each time data are relocated without being changed by the host system, this increases the write amplification and thus reduces the life of the flash memory. The key is to find an optimal algorithm which maximizes them both.[39]

Separating static and dynamic data

[edit]The separation of static (cold) and dynamic (hot) data to reduce write amplification is not a simple process for the SSD controller. The process requires the SSD controller to separate the LBAs with data which is constantly changing and requiring rewriting (dynamic data) from the LBAs with data which rarely changes and does not require any rewrites (static data). If the data is mixed in the same blocks, as with almost all systems today, any rewrites will require the SSD controller to rewrite both the dynamic data (which caused the rewrite initially) and static data (which did not require any rewrite). Any garbage collection of data that would not have otherwise required moving will increase write amplification. Therefore, separating the data will enable static data to stay at rest and if it never gets rewritten it will have the lowest possible write amplification for that data. The drawback to this process is that somehow the SSD controller must still find a way to wear level the static data because those blocks that never change will not get a chance to be written to their maximum P/E cycles.[1]

Performance implications

[edit]Sequential writes

[edit]When an SSD is writing large amounts of data sequentially, the write amplification is equal to one meaning there is less write amplification. The reason is as the data is written, the entire (flash) block is filled sequentially with data related to the same file. If the OS determines that file is to be replaced or deleted, the entire block can be marked as invalid, and there is no need to read parts of it to garbage collect and rewrite into another block. It will need only to be erased, which is much easier and faster than the read–erase–modify–write process needed for randomly written data going through garbage collection.[7]

Random writes

[edit]The peak random write performance on an SSD is driven by plenty of free blocks after the SSD is completely garbage collected, secure erased, 100% TRIMed, or newly installed. The maximum speed will depend upon the number of parallel flash channels connected to the SSD controller, the efficiency of the firmware, and the speed of the flash memory in writing to a page. During this phase the write amplification will be the best it can ever be for random writes and will be approaching one. Once the blocks are all written once, garbage collection will begin and the performance will be gated by the speed and efficiency of that process. Write amplification in this phase will increase to the highest levels the drive will experience.[7]

Impact on performance

[edit]The overall performance of an SSD is dependent upon a number of factors, including write amplification. Writing to a flash memory device takes longer than reading from it.[17] An SSD generally uses multiple flash memory components connected in parallel as channels to increase performance. If the SSD has a high write amplification, the controller will be required to write that many more times to the flash memory. This requires even more time to write the data from the host. An SSD with a low write amplification will not need to write as much data and can therefore be finished writing sooner than a drive with a high write amplification.[1][8]

Product statements

[edit]In September 2008, Intel announced the X25-M SATA SSD with a reported WA as low as 1.1.[5][40] In April 2009, SandForce announced the SF-1000 SSD Processor family with a reported WA of 0.5 which uses data compression to achieve a sub 1.0 WA.[5][41] Before this announcement, a write amplification of 1.0 was considered the lowest that could be attained with an SSD.[17]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hu, X.-Y.; E. Eleftheriou; R. Haas; I. Iliadis; R. Pletka (2009). Write Amplification Analysis in Flash-Based Solid State Drives. IBM. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.154.8668.

- ^ a b c d Thatcher, Jonathan (2009-08-18). "NAND Flash Solid State Storage Performance and Capability – an In-depth Look" (PDF). SNIA. Retrieved 2012-08-28.

- ^ a b c Smith, Kent (2009-08-17). "Benchmarking SSDs: The Devil is in the Preconditioning Details" (PDF). SandForce. Retrieved 2016-11-10.

- ^ a b c Lucchesi, Ray (September 2008). "SSD Flash drives enter the enterprise" (PDF). Silverton Consulting. Retrieved 2010-06-18.

- ^ a b c Shimpi, Anand Lal (2009-12-31). "OCZ's Vertex 2 Pro Preview: The Fastest MLC SSD We've Ever Tested". AnandTech. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- ^ Ku, Andrew (6 February 2012). "Intel SSD 520 Review: SandForce's Technology: Very Low Write Amplification". TomsHardware. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d Hu, X.-Y. & R. Haas (2010-03-31). "The Fundamental Limit of Flash Random Write Performance: Understanding, Analysis and Performance Modelling" (PDF). IBM Research, Zurich. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ^ a b Agrawal, N., V. Prabhakaran, T. Wobber, J. D. Davis, M. Manasse, R. Panigrahy (June 2008). Design Tradeoffs for SSD Performance. Microsoft. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.141.1709.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Case, Loyd (2008-09-08). "Intel X25 80GB Solid-State Drive Review". Extremetech. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ^ Kerekes, Zsolt. "Western Digital Solid State Storage – formerly SiliconSystems". ACSL. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ^ a b c d e "SSDs – Write Amplification, TRIM and GC" (PDF). OCZ Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-31. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ^ "Intel Solid State Drives". Intel. Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- ^ "TN-FD-23: Calculating Write Amplification Factor" (PDF). Micron. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ a b Kerekes, Zsolt. "Flash SSD Jargon Explained". ACSL. Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- ^ "TN-29-17: NAND Flash Design and Use Considerations" (PDF). Micron. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ a b c d Mehling, Herman (2009-12-01). "Solid State Drives Take Out the Garbage". Enterprise Storage Forum. Retrieved 2010-06-18.

- ^ a b c Conley, Kevin (2010-05-27). "Corsair Force Series SSDs: Putting a Damper on Write Amplification". Corsair Blog. Corsair.com. Retrieved 2010-06-18.

- ^ a b Layton, Jeffrey B. (2009-10-27). "Anatomy of SSDs". Linux Magazine. Archived from the original on October 31, 2009. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ^ Bell, Graeme B. (2010). "Solid State Drives: The Beginning of the End for Current Practice in Digital Forensic Recovery?" (PDF). Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-05. Retrieved 2012-04-02.

- ^ a b Christiansen, Neal (2009-09-14). "ATA Trim/Delete Notification Support in Windows 7" (PDF). Storage Developer Conference, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-26. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ^ a b c Shimpi, Anand Lal (2009-11-17). "The SSD Improv: Intel & Indilinx get TRIM, Kingston Brings Intel Down to $115". AnandTech.com. Archived from the original on April 3, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mehling, Herman (2010-01-27). "Solid State Drives Get Faster with TRIM". Enterprise Storage Forum. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ^ "Enable TRIM for All SSD's [sic] in Mac OS X Lion". osxdaily.com. 2012-01-03. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- ^ "FreeBSD 8.1-RELEASE Release Notes". FreeBSD.org.

- ^ "Linux 2.6.33 Features". KernelNewbies.org. 2010-02-04. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ^ a b c d Bagley, Jim (2009-07-01). "Managing data migration, Tier 1 to SSD Tier 0: Over-provisioning: a winning strategy or a retreat?" (PDF). plianttechnology.com. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-02. Retrieved 2016-06-21.

- ^ a b Drossel, Gary (2009-09-14). "Methodologies for Calculating SSD Useable Life" (PDF). Storage Developer Conference, 2009. Retrieved 2010-06-20.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Smith, Kent (2011-08-01). "Understanding SSD Over-provisioning" (PDF). FlashMemorySummit.com. p. 14. Retrieved 2012-12-03.

- ^ Shimpi, Anand Lal (2010-05-03). "The Impact of Spare Area on SandForce, More Capacity At No Performance Loss?". AnandTech.com. p. 2. Archived from the original on May 6, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ^ OBrien, Kevin (2012-02-06). "Intel SSD 520 Enterprise Review". Storage Review. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

20% over-provisioning adds substantial performance in all profiles with write activity

- ^ "White Paper: Over-Provisioning an Intel SSD" (PDF). Intel. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 25, 2011. Retrieved 2012-11-29. Alt URL

- ^ Shimpi, Anand Lal (2009-03-18). "The SSD Anthology: Understanding SSDs and New Drives from OCZ". AnandTech.com. p. 9. Retrieved 2010-06-20.[dead link]

- ^ Shimpi, Anand Lal (2009-03-18). "The SSD Anthology: Understanding SSDs and New Drives from OCZ". AnandTech.com. p. 11. Archived from the original on April 28, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ^ a b Malventano, Allyn (2009-02-13). "Long-term performance analysis of Intel Mainstream SSDs". PC Perspective. Archived from the original on 2010-02-21. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ^ "CMRR – Secure Erase". CMRR. Archived from the original on 2012-07-02. Retrieved 2010-06-21.

- ^ OCZ Technology (2011-09-07). "How to Secure Erase Your OCZ SSD Using a Bootable Linux CD". Archived from the original on 2012-01-07. Retrieved 2014-12-13.

- ^ "The Intel SSD 320 Review: 25nm G3 is Finally Here". anandtech. Archived from the original on April 10, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- ^ "SSD Secure Erase – Ziele eines Secure Erase" [Secure Erase – Goals of the Secure Erase] (in German). Thomas-Krenn.AG. 2017-03-17. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- ^ Chang, Li-Pin (2007-03-11). On Efficient Wear Leveling for Large Scale Flash Memory Storage Systems. National ChiaoTung University, HsinChu, Taiwan. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.103.4903.

- ^ "Intel Introduces Solid-State Drives for Notebook and Desktop Computers". Intel. 2008-09-08. Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- ^ "SandForce SSD Processors Transform Mainstream Data Storage" (PDF). SandForce. 2008-09-08. Retrieved 2010-05-31.

External links

[edit] Media related to Write amplification at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Write amplification at Wikimedia Commons