Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

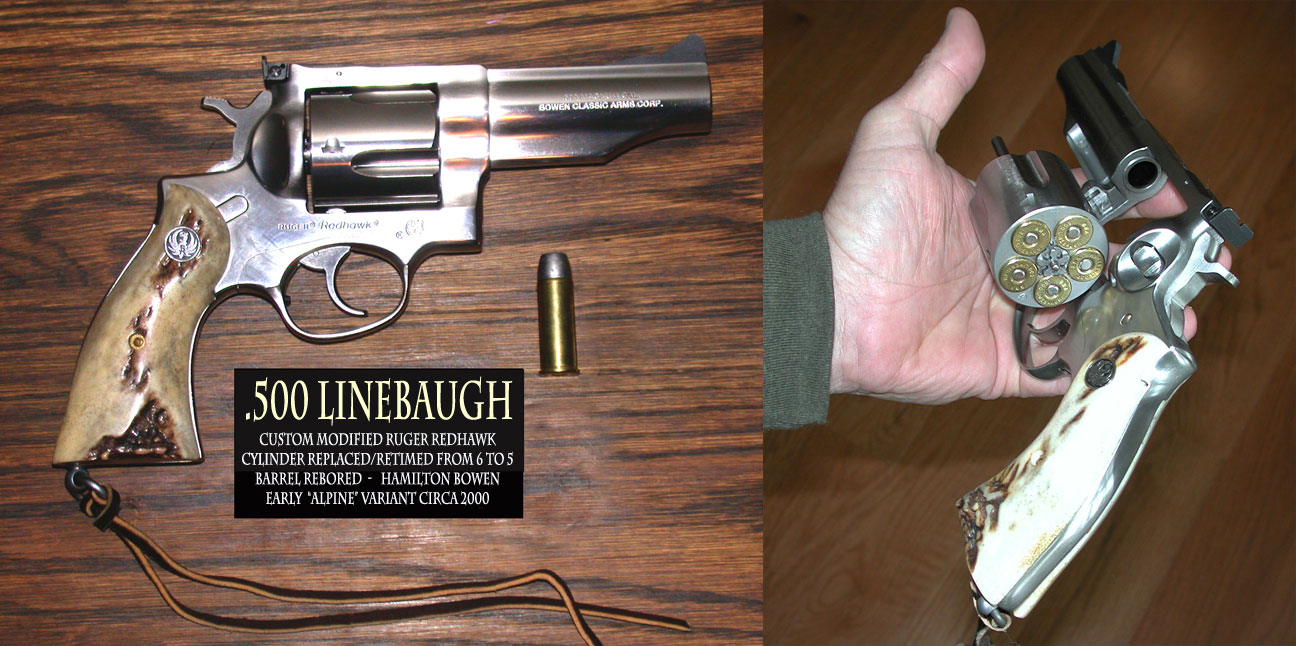

.500 Linebaugh

View on Wikipedia| .500 Linebaugh | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Type | Handgun cartridge | |||||||||||

| Place of origin | United States | |||||||||||

| Production history | ||||||||||||

| Designer | John Linebaugh | |||||||||||

| Designed | 1986 | |||||||||||

| Variants | .500 Linebaugh Long or .500 Linebaugh Maximum | |||||||||||

| Specifications | ||||||||||||

| Parent case | .348 Winchester | |||||||||||

| Case type | Rimmed, straight | |||||||||||

| Bullet diameter | .510 in (13.0 mm) | |||||||||||

| Neck diameter | .540 in (13.7 mm) | |||||||||||

| Base diameter | .553 in (14.0 mm) | |||||||||||

| Rim diameter | .610 in (15.5 mm) | |||||||||||

| Rim thickness | .065 in (1.7 mm) | |||||||||||

| Case length | 1.405 in (35.7 mm) | |||||||||||

| Overall length | 1.755 in (44.6 mm) | |||||||||||

| Primer type | Large rifle | |||||||||||

| Ballistic performance | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Source: http://www.buffalobore.com | ||||||||||||

The .500 Linebaugh (13x35mmR) is a .50 caliber handgun cartridge designed for use in revolvers.[1]

History

[edit]Inspired by the existing .50 WT Super cartridge devised by Neil Wheeler and Bill Topping of Sandy, Utah, John Linebaugh developed the .500 Linebaugh cartridge in 1986.[2] Linebaugh was then known for converting six-shot .45 Colt revolvers to five-shot configuration, which allowed the use of higher-pressure ammunition than would be safe in many existing firearms chambered for the cartridge. While this venture was a success, Linebaugh was intrigued by Wheeler and Topping's work, and decided to pursue a .50 caliber handgun cartridge of his own.[1]

The cartridge case itself was designed by cutting off the .348 Winchester case to 1.405 in (35.7 mm), opening the case mouth to accept a .510 caliber (12.95 mm) bullet, and reaming the inside of the case. The first revolvers converted to use the .500 Linebaugh were the Ruger Bisley and the Seville revolvers. Due to the demise of the Seville revolvers in the early 1990s, most subsequent conversions have been carried out on revolvers based on the Ruger Bisley frame.[3]

It was when the supply of .348 Winchester cases started running out that John Linebaugh began working on the .475 Linebaugh, which could be formed from the more available .45-70 Government cases. When the Winchester Model 71 was reintroduced in the .348 Winchester, the ability to form .500 Linebaugh cases again became feasible.[1] Today, Starline and Buffalo Bore offer .500 Linebaugh cases which are not dependent on the supply of .348 Winchester cases.

Cartridge design and specifications

[edit]The .500 Linebaugh is a proprietary cartridge and thus has not been adopted by mainline firearms manufacturers. Currently the only firearm manufacturer that produces a revolver for this cartridge is Magnum Research (owned by Kahr Firearms Group), in the BFR product line. Prior to January 2019, the only alternative was to have a gunsmith such as John Linebaugh of Linebaugh Custom Six guns or Hamilton Bowen of Bowen Classic Arms convert pre-existing revolvers such as the Ruger Blackhawk and Bisley to fire the cartridge. Bowen is known to have converted the Ruger Redhawk double-action revolver for use with this cartridge.

Due to the proprietary status of the cartridge neither the CIP nor SAAMI have published official specifications for the cartridge. As is the case, there can be some variations from gunsmith to gunsmith. No pressure standard has been published for the cartridge but according to Linebaugh, pressure levels between 30,000 psi (210 MPa) and 35,000 psi (240 MPa) are considered safe in the converted revolvers.

The cartridge uses .510 in (12.95 mm) diameter jacketed bullets or .511-.512 in (12.98-13.01 mm) lead bullets.

Sporting usage

[edit]The .500 Linebaugh was designed as a hunting cartridge. It was designed to fire a 440 gr (29 g) bullet at 1,300 ft/s (400 m/s).[4] This particular loading generates 1,650 ft⋅lbf (2,240 J) of energy making this one of the most powerful handgun cartridges put into production. In terms of energy, this is comparable to the .454 Casull cartridge. However, the .500 Linebaugh provides a larger diameter, heavier bullet with a greater sectional density than the .454 Casull. As a hunting cartridge it is capable of taking any North American game animals and most African game species.[1]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Barnes, Frank C. (2006) [1965]. Skinner, Stan (ed.). Cartridges of the World (11th ed.). Gun Digest Books. p. 278. ISBN 0-89689-297-2.

- ^ "Gun Talk: Custom Six Guns; Life-Saving Training; Collecting Guns: Gun Talk Radio | 7.07.19 C". guntalk.libsyn.com. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ Quinn, Jeff (23 August 2004). "The .500 Linebaugh". gunblast.com. Gunblast. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ ".500 Linebaugh Ammo". Buffalo Bore Ammunition. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

External links

[edit].500 Linebaugh

View on GrokipediaHistory and Development

Origins and Invention

John Linebaugh, a custom gunsmith based in Cody, Wyoming, gained prominence in the 1980s for his innovative work on big-bore handgun cartridges, driven by a passion for maximizing revolver power while maintaining reliability.[10] Born in Missouri in 1955, Linebaugh had relocated to Wyoming by 1976, where he honed his skills in custom firearm modifications, particularly for hunting applications that demanded superior stopping power. Linebaugh passed away on March 19, 2023, at his home in Clark, Wyoming.[11][10] His focus on enhancing cartridge performance stemmed from the limitations of existing magnum rounds, inspiring him to push the boundaries of handgun ballistics.[12] In 1986, Linebaugh developed the .500 Linebaugh cartridge through meticulous experimentation, starting with conversions of .45 Colt six-shot revolvers into five-shot configurations to provide additional steel support around the larger chambers and prevent frame stress under high pressures.[2] This approach allowed the use of more robust cylinders capable of handling the increased dimensions and loads without requiring entirely new frame designs.[3] The parent case for the .500 Linebaugh was derived from shortened and reformed .348 Winchester rifle brass, which was necked down to a .510-inch bullet diameter to optimize case capacity and enhance overall strength for high-pressure applications.[1] This design choice leveraged the rimmed structure of the .348 Winchester for reliable extraction in revolvers while providing sufficient volume for heavy powder charges.[3] Linebaugh's primary motivation was to engineer a revolver cartridge that surpassed the .454 Casull in raw power, tailored for big-game hunting where deep penetration and massive energy transfer were essential against large animals.[1] The cartridge was optimized for cast lead bullets in the 410- to 440-grain range, delivering authoritative performance from single-action revolvers.[2] Early prototyping included extensive handloading trials with both jacketed and cast lead projectiles, achieving muzzle velocities up to approximately 1,300 feet per second when fired from 7.5-inch barrels, confirming the cartridge's potential for extreme handgun ballistics.[13] These tests validated the design's safety and efficacy, marking a significant advancement in big-bore revolver technology.[14]Evolution and Commercialization

The .500 Linebaugh emerged as a wildcat cartridge in 1986, handloaded by enthusiasts using modified .348 Winchester brass, but transitioned to limited commercial availability in the late 1990s when Buffalo Bore Ammunition became the first manufacturer to offer factory-loaded rounds in 1997. This marked a pivotal shift from purely custom reloading to accessible ammunition, enabling broader experimentation among big-bore revolver shooters despite the cartridge's demanding recoil and power. Grizzly Cartridge later joined as another boutique producer, further solidifying its niche commercial presence.[15][16][17] Handgun hunting enthusiasts played a key role in promoting the .500 Linebaugh, highlighting its potential for ethical big-game harvests through specialized publications, forums, and organizations focused on revolver-based hunting. Custom gunsmiths like John Linebaugh and Hamilton Bowen advanced its adoption by converting popular platforms, such as Ruger Super Redhawk double-action and Blackhawk single-action revolvers, into five-shot configurations optimized for the cartridge's dimensions and pressures. These modifications, often involving rebarreling and cylinder work, became the standard for early users seeking reliable performance.[11][18][19] A major milestone arrived in 2019 with the introduction of the Magnum Research BFR, the first factory revolver chambered specifically for the .500 Linebaugh, offering a robust single-action design without the need for custom alterations. However, reluctance from major manufacturers persisted due to the cartridge's specialized market and intense recoil, which limited mass production and kept reliance on skilled gunsmiths for most firearms.[20][3] By the mid-2020s, the .500 Linebaugh maintained interest within the single-action revolver community, supported by the BFR's availability and aftermarket components such as reloading dies from Lee Precision and cast bullets from Missouri Bullet Company.[4][21] This has fostered use among dedicated shooters, though it remains a boutique option rather than a mainstream caliber.Design and Specifications

Cartridge Construction

The .500 Linebaugh cartridge is constructed from high-quality brass cases reformed from .348 Winchester rifle brass, which are cut down, resized, and fitted with a large rifle primer pocket; headstamps are typically marked ".500 Linebaugh" on commercial brass from manufacturers like Starline or Buffalo Bore, though custom or early cases may be unmarked.[1][9][22] Key dimensions include an overall cartridge length of approximately 1.755 inches, a case length of 1.405 inches, a rim diameter of 0.610 inches, and a base diameter of 0.553 inches, with the neck measuring 0.540 inches in diameter.[5][23][24] The bullet diameter is 0.510 inches, allowing for a range of projectiles from 350 to 600 grains, though common choices include 440-grain cast lead bullets for general use or 400-grain jacketed bullets for hunting applications.[25][4][16] The case employs a near-straight-walled design with a subtle bottleneck at the neck and shoulder to promote reliable feeding in revolver cylinders, featuring a neck wall thickness of about 0.020 inches to safely contain operating pressures up to 35,000–40,000 psi in non-SAAMI-standardized loads. As a wildcat cartridge without official SAAMI specifications, pressure limits should follow gunsmith or manufacturer recommendations for safe use in custom revolvers.[1][26][27] Visually, the rimmed case resembles a shortened .45-70 Government cartridge but is specifically engineered for the demands of handgun pressures and single-action revolver operation, providing robust headspacing and extraction.[3]Ballistic Performance

The .500 Linebaugh cartridge delivers substantial ballistic performance, characterized by high muzzle energies suitable for big-game applications. Representative standard loads include a 435-grain LBT-LFN bullet achieving 1,300 fps from a typical revolver barrel, producing approximately 1,632 ft-lbs of muzzle energy.[6] High-performance loads push a 400-grain jacketed hollow-point to 1,400 fps, yielding 1,741 ft-lbs of energy, while reduced-recoil options, such as a 435-grain LBT-LFN at 950 fps, generate 871 ft-lbs for practice or lighter shooting.[28][29] Heavier bullets, like 525-grain LBT-LFN at 1,100 fps, provide 1,410 ft-lbs, balancing penetration with manageable recoil.[8]| Bullet Weight (gr) | Type | Velocity (fps) | Muzzle Energy (ft-lbs) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 435 | LBT-LFN | 1,300 | 1,632 | Standard heavy load for dangerous game |

| 400 | JHP | 1,400 | 1,741 | High-velocity expanding option |

| 435 | LBT-LFN | 950 | 871 | Low-recoil practice load |

| 525 | LBT-LFN | 1,100 | 1,410 | Heavy bullet for deep penetration |