Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Face (geometry)

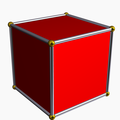

View on WikipediaIn solid geometry, a face is a flat surface (a planar region) that forms part of the boundary of a solid object. For example, a cube has six faces in this sense.

In more modern treatments of the geometry of polyhedra and higher-dimensional polytopes, a "face" is defined in such a way that it may have any dimension. The vertices, edges, and (2-dimensional) faces of a polyhedron are all faces in this more general sense.[1]

Polygonal face

[edit]In elementary geometry, a face is a polygon[2] on the boundary of a polyhedron.[1][3] (Here a "polygon" should be viewed as including the 2-dimensional region inside it.) Other names for a polygonal face include polyhedron side and Euclidean plane tile.

For example, any of the six squares that bound a cube is a face of the cube. Sometimes "face" is also used to refer to the 2-dimensional features of a 4-polytope. With this meaning, the 4-dimensional tesseract has 24 square faces, each sharing two of 8 cubic cells.

| Polyhedron | Star polyhedron | Euclidean tiling | Hyperbolic tiling | 4-polytope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| {4,3} | {5/2,5} | {4,4} | {4,5} | {4,3,3} |

The cube has 3 square faces per vertex. |

The small stellated dodecahedron has 5 pentagrammic faces per vertex. |

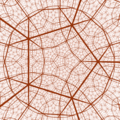

The square tiling in the Euclidean plane has 4 square faces per vertex. |

The order-5 square tiling has 5 square faces per vertex. |

The tesseract has 3 square faces per edge. |

Number of polygonal faces of a polyhedron

[edit]Any convex polyhedron's surface has Euler characteristic

where V is the number of vertices, E is the number of edges, and F is the number of faces. This equation is known as Euler's polyhedron formula. Thus the number of faces is 2 more than the excess of the number of edges over the number of vertices. For example, a cube has 12 edges and 8 vertices, and hence 6 faces.

k-face

[edit]In higher-dimensional geometry, the faces of a polytope are features of all dimensions.[4][5] A face of dimension k is sometimes called a k-face. For example, the polygonal faces of an ordinary polyhedron are 2-faces. The word "face" is defined differently in different areas of mathematics. For example, many but not all authors allow the polytope itself and the empty set as faces of a polytope, where the empty set is for consistency given a "dimension" of −1. For any n-dimensional polytope, faces have dimension with .

For example, with this meaning, the faces of a cube comprise the cube itself (a 3-face), its (square) facets (2-faces), its (line segment) edges (1-faces), its (point) vertices (0-faces), and the empty set.

In some areas of mathematics, such as polyhedral combinatorics, a polytope is by definition convex. In this setting, there is a precise definition: a face of a polytope P in Euclidean space is the intersection of P with any closed halfspace whose boundary is disjoint from the relative interior of P.[6] According to this definition, the set of faces of a polytope includes the polytope itself and the empty set.[4][5] For convex polytopes, this definition is equivalent to the general definition of a face of a convex set, given below.

In other areas of mathematics, such as the theories of abstract polytopes and star polytopes, the requirement of convexity is relaxed. One precise combinatorial concept that generalizes some earlier types of polyhedra is the notion of a simplicial complex. More generally, there is the notion of a polytopal complex.

An n-dimensional simplex (line segment (n = 1), triangle (n = 2), tetrahedron (n = 3), etc.), defined by n + 1 vertices, has a face for each subset of the vertices, from the empty set up through the set of all vertices. In particular, there are 2n + 1 faces in total. The number of k-faces, for k ∈ {−1, 0, ..., n}, is the binomial coefficient .

There are specific names for k-faces depending on the value of k and, in some cases, how close k is to the dimension n of the polytope.

Vertex or 0-face

[edit]Vertex is the common name for a 0-face.

Edge or 1-face

[edit]Edge is the common name for a 1-face.

Face or 2-face

[edit]The use of face in a context where a specific k is meant for a k-face but is not explicitly specified is commonly a 2-face.

Cell or 3-face

[edit]A cell is a polyhedral element (3-face) of a 4-dimensional polytope or 3-dimensional tessellation, or higher. Cells are facets for 4-polytopes and 3-honeycombs.

Examples:

| 4-polytopes | 3-honeycombs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| {4,3,3} | {5,3,3} | {4,3,4} | {5,3,4} |

The tesseract has 3 cubic cells (3-faces) per edge. |

The 120-cell has 3 dodecahedral cells (3-faces) per edge. |

The cubic honeycomb fills Euclidean 3-space with cubes, with 4 cells (3-faces) per edge. |

The order-4 dodecahedral honeycomb fills 3-dimensional hyperbolic space with dodecahedra, 4 cells (3-faces) per edge. |

Facet or (n − 1)-face

[edit]In higher-dimensional geometry, the facets of a n-polytope are the (n − 1)-faces (faces of dimension one less than the polytope itself).[7] A polytope is bounded by its facets.

For example:

- The facets of a line segment are its 0-faces or vertices.

- The facets of a polygon are its 1-faces or edges.

- The facets of a polyhedron or plane tiling are its 2-faces.

- The facets of a 4D polytope or 3-honeycomb are its 3-faces or cells.

- The facets of a 5D polytope or 4-honeycomb are its 4-faces.

Ridge or (n − 2)-face

[edit]In related terminology, the (n − 2)-faces of an n-polytope are called ridges (also subfacets).[8] A ridge is seen as the boundary between exactly two facets of a polytope or honeycomb.

For example:

- The ridges of a 2D polygon or 1D tiling are its 0-faces or vertices.

- The ridges of a 3D polyhedron or plane tiling are its 1-faces or edges.

- The ridges of a 4D polytope or 3-honeycomb are its 2-faces or simply faces.

- The ridges of a 5D polytope or 4-honeycomb are its 3-faces or cells.

Peak or (n − 3)-face

[edit]The (n − 3)-faces of an n-polytope are called peaks. A peak contains a rotational axis of facets and ridges in a regular polytope or honeycomb.

For example:

- The peaks of a 3D polyhedron or plane tiling are its 0-faces or vertices.

- The peaks of a 4D polytope or 3-honeycomb are its 1-faces or edges.

- The peaks of a 5D polytope or 4-honeycomb are its 2-faces or simply faces.

Face of a convex set

[edit]

The notion of a face can be generalized from convex polytopes to all convex sets, as follows. Let be a convex set in a real vector space . A face of is a convex subset such that whenever a point lies strictly between two points and in , both and must be in . Equivalently, for any and any real number such that is in , and must be in .[9]

According to this definition, itself and the empty set are faces of ; these are sometimes called the trivial faces of .

An extreme point of is a point such that is a face of .[9] That is, if lies between two points , then .

For example:

- A triangle in the plane (including the region inside) is a convex set. Its nontrivial faces are the three vertices and the three edges. (So the only extreme points are the three vertices.)

- The only nontrivial faces of the closed unit disk are its extreme points, namely the points on the unit circle .

Let be a convex set in that is compact (or equivalently, closed and bounded). Then is the convex hull of its extreme points.[10] More generally, each compact convex set in a locally convex topological vector space is the closed convex hull of its extreme points (the Krein–Milman theorem).

An exposed face of is the subset of points of where a linear functional achieves its minimum on . Thus, if is a linear functional on and , then is an exposed face of .

An exposed point of is a point such that is an exposed face of . That is, for all . See the figure for examples of extreme points that are not exposed.

Competing definitions

[edit]Some authors do not include and/or as faces of . Some authors require a face to be a closed subset; this is automatic for a compact convex set in a vector space of finite dimension, but not in infinite dimensions.[11] In infinite dimensions, the functional is usually assumed to be continuous in a given vector topology.

Properties

[edit]An exposed face of a convex set is a face. In particular, it is a convex subset.

If is a face of a convex set , then a subset is a face of if and only if is a face of .

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Matoušek 2002, p. 86.

- ^ Some other polygons, which are not faces, have also been considered for polyhedra and tilings. These include Petrie polygons, vertex figures and facets (flat polygons formed by coplanar vertices that do not lie in the same face of the polyhedron).

- ^ Cromwell, Peter R. (1999), Polyhedra, Cambridge University Press, p. 13, ISBN 9780521664059.

- ^ a b Grünbaum 2003, p. 17.

- ^ a b Ziegler 1995, p. 51.

- ^ Matoušek (2002) and Ziegler (1995) use a slightly different but equivalent definition, which amounts to intersecting P with either a hyperplane disjoint from the interior of P or the whole space.

- ^ Matoušek (2002), p. 87; Grünbaum (2003), p. 27; Ziegler (1995), p. 17.

- ^ Matoušek (2002), p. 87; Ziegler (1995), p. 71.

- ^ a b Rockafellar 1997, p. 162.

- ^ Rockafellar 1997, p. 166.

- ^ Simon, Barry (2011). Convexity: an Analytic Viewpoint. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-107-00731-4. MR 2814377.

Bibliography

[edit]- Grünbaum, Branko (2003), Convex Polytopes, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 221 (2nd ed.), Springer, ISBN 0-387-00424-6, MR 1976856

- Matoušek, Jiří (2002), Lectures in Discrete Geometry, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 212, Springer, ISBN 9780387953748, MR 1899299

- Rockafellar, R. T. (1997) [1970]. Convex Analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 1-4008-7317-7. MR 0274683.

- Ziegler, Günter M. (1995), Lectures on Polytopes, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 152, Springer, ISBN 9780387943657, MR 1311028

External links

[edit]Face (geometry)

View on GrokipediaFaces in Polyhedra

Definition of Polygonal Faces

In geometry, a face of a polyhedron is defined as a flat, two-dimensional polygonal surface that bounds the solid, typically convex and enclosed by straight edges connecting vertices.[9] These faces form the boundary components of the polyhedron, ensuring it is a closed three-dimensional shape without gaps or overlaps.[10] Faces possess specific geometric and topological properties: they are planar, meaning all points lie in a single plane, and constitute simple polygons—closed chains of at least three edges that are connected and free of self-intersections.[9] Each edge of a face is shared precisely by two adjacent faces, maintaining the polyhedron's integrity, while every vertex on a face connects to at least three faces to prevent collapse into a lower-dimensional form.[9] Common face types include triangles, quadrilaterals, and pentagons, which must satisfy convexity to ensure the overall polyhedron remains convex.[11] Representative examples illustrate these properties. In a tetrahedron, each of the four faces is an equilateral triangle, providing a minimal convex enclosure.[10] The dodecahedron features twelve regular pentagonal faces, where each pentagon is bounded by five equal edges and angles, demonstrating how polygonal faces can vary while adhering to planarity and simplicity.[11] Faces play a central role in Euler's formula for convex polyhedra, which relates the number of vertices , edges , and faces via , capturing the topological structure where faces contribute directly to the characteristic count.[10] Historically, the concept of polygonal faces originated with the study of Platonic solids in ancient Greece, where Plato associated these regular polyhedra—each with identical regular polygonal faces—with the classical elements, a framework later formalized by Euclid in his Elements.[11]Enumeration and Formulas for Faces

Euler's polyhedron formula provides a fundamental relation for counting the faces of a convex polyhedron, stating that for any convex polyhedron, the number of vertices , edges , and faces satisfy . This equation holds for simply connected polyhedra of genus 0, equivalent to those topologically equivalent to a sphere. The formula originates from Euler's work in 1752 and can be derived using graph theory by considering the polyhedron's skeleton as a connected planar graph embedded on a sphere, where the Euler characteristic reflects the topology of the surface; each face, including the infinite outer face in the planar embedding, contributes to the count. In topological terms, this generalizes to the Euler characteristic for surfaces, as extended by Poincaré, confirming the invariant value of 2 for spherical topology.[12] Specific examples illustrate the formula's application in enumerating faces for regular polyhedra, known as Platonic solids. The tetrahedron has 4 triangular faces, the cube has 6 square faces, the octahedron has 8 triangular faces, the dodecahedron has 12 pentagonal faces, and the icosahedron has 20 triangular faces. These counts satisfy Euler's formula; for instance, the icosahedron has , , and , yielding . The following table summarizes the face counts for the five Platonic solids:| Solid | Number of Faces | Face Type |

|---|---|---|

| Tetrahedron | 4 | Triangle |

| Cube | 6 | Square |

| Octahedron | 8 | Triangle |

| Dodecahedron | 12 | Pentagon |

| Icosahedron | 20 | Triangle |