Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Address space

View on WikipediaThis section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2025) |

In computing, an address space defines a range of discrete addresses, each of which may correspond to a network host, peripheral device, disk sector, a memory cell or other logical or physical entity.

For software programs to save and retrieve stored data, each datum must have an address where it can be located. The number of address spaces available depends on the underlying address structure, which is usually limited by the computer architecture being used. Often an address space in a system with virtual memory corresponds to a highest level translation table, e.g., a segment table in IBM System/370.

Address spaces are created by combining enough uniquely identified qualifiers to make an address unambiguous within the address space. For a person's physical address, the address space would be a combination of locations, such as a neighborhood, town, city, or country. Some elements of a data address space may be the same, but if any element in the address is different, addresses in said space will reference different entities. For example, there could be multiple buildings at the same address of "32 Main Street" but in different towns, demonstrating that different towns have different, although similarly arranged, street address spaces.

An address space usually provides (or allows) a partitioning to several regions according to the mathematical structure it has. In the case of total order, as for memory addresses, these are simply chunks. Like the hierarchical design of postal addresses, some nested domain hierarchies appear as a directed ordered tree, such as with the Domain Name System or a directory structure. In the Internet, the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) allocates ranges of IP addresses to various registries so each can manage their parts of the global Internet address space.[1]

Examples

[edit]Uses of addresses include, but are not limited to the following:

- Memory addresses for main memory, memory-mapped I/O, as well as for virtual memory;

- Device addresses on an expansion bus;

- Sector addressing for disk drives;

- File names on a particular volume;

- Various kinds of network host addresses in computer networks;

- Uniform resource locators in the Internet.

Address mapping and translation

[edit]

Another common feature of address spaces are mappings and translations, often forming numerous layers. This usually means that some higher-level address must be translated to lower-level ones in some way. For example, a file system on a logical disk operates using linear sector numbers, which have to be translated to absolute LBA sector addresses, in simple cases, via addition of the partition's first sector address. Then, for a disk drive connected via Parallel ATA, each of them must be converted to logical cylinder-head-sector address due to the interface historical shortcomings. It is converted back to LBA by the disk controller, then, finally, to physical cylinder, head and sector numbers.

The Domain Name System maps its names to and from network-specific addresses (usually IP addresses), which in turn may be mapped to link layer network addresses via Address Resolution Protocol. Network address translation may also occur on the edge of different IP spaces, such as a local area network and the Internet.

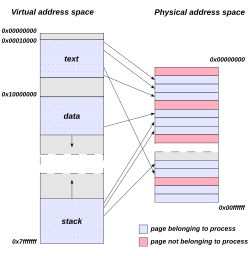

An iconic example of virtual-to-physical address translation is virtual memory, where different pages of virtual address space map either to page file or to main memory physical address space. It is possible that several numerically different virtual addresses all refer to one physical address and hence to the same physical byte of RAM. It is also possible that a single virtual address maps to one, one, or more than one physical address.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "IPv4 Address Space Registry". Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA). Archived from the original on April 30, 2010. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

Address space

View on GrokipediaBasic Concepts

Definition

In computing, an address space is defined as the range of discrete addresses available to a computer system for identifying and accessing memory locations or other resources, such as peripherals or storage sectors.[7] This range is typically represented as a contiguous sequence of bit patterns, where each unique address corresponds to a specific location within the system's memory hierarchy.[8] The concept enables efficient referencing of data and instructions, forming the foundation for memory management in both hardware and software environments. The term "address space" originated in the context of early computer memory management during the late 1950s and 1960s, with the term notably formalized by Jack Dennis in 1965 in the design of the Multics operating system, evolving from fixed addressing schemes in machines like the IBM 7090, which featured a 15-bit address field supporting 32,768 words of core memory.[9] This development was influenced by pioneering systems such as the Atlas computer at the University of Manchester, where distinctions between program-generated addresses and physical memory locations first highlighted the need for abstracted addressing to handle limited hardware resources.[10] By the mid-1960s, the concept had become integral to multiprogramming systems, allowing multiple processes to operate within isolated address ranges. In computing, address space primarily pertains to memory addressing mechanisms in hardware architectures and operating systems, distinct from analogous uses in networking, such as IP address spaces that delineate ranges of protocol identifiers for devices.[7] Key attributes include its size, which is determined by the width of the address bus—for instance, a 32-bit address space accommodates up to 4 GB (2^{32} bytes) of addressable memory—and its conventional starting point at address 0.[11] Address spaces may be physical, tied directly to hardware, or virtual, providing an illusion of larger, contiguous memory to software, though these distinctions are elaborated elsewhere.Components and Units

An address in an address space is structured as a binary number consisting of a fixed number of bits, where each bit position represents a successive power of 2, enabling the enumeration of discrete locations from 0 to for an -bit address.[12] This binary representation forms the foundational unit of addressing in computer memory, with the least significant bit corresponding to and higher bits scaling exponentially.[13] For instance, a 32-bit address uses bits 0 through 31 to specify up to unique positions.[14] The addressable unit defines the smallest granularity of memory that can be directly referenced by an address, typically a byte of 8 bits in modern systems.[13] Byte-addressable architectures, such as x86 and MIPS, assign a unique address to every byte, allowing precise access to individual bytes within larger data structures like words or cache lines.[14] In contrast, word-addressable systems treat the word—often 32 or 64 bits—as the basic unit, where each address points to an entire word rather than its constituent bytes, requiring additional byte-selection mechanisms for sub-word access.[14] This distinction affects memory efficiency and programming models, with byte-addressability predominating in contemporary designs for its flexibility.[14] The total size of an address space is determined by the formula , where is the number of address bits and is the size of the addressable unit in bytes; in byte-addressable systems, this simplifies to bytes.[13] For a 32-bit byte-addressable space, the maximum addressable memory is thus bytes, equivalent to 4,294,967,296 bytes or 4 GB.[13] Similarly, 64-bit systems support up to bytes, or 16 exbibytes, though practical implementations may limit this due to hardware constraints.[13]Types of Address Spaces

Physical Address Space

The physical address space encompasses the range of actual locations in a computer's hardware memory, such as RAM, where data and instructions are stored. It is defined by the physical addresses generated directly by the processor to access these hardware components, without any intermediary abstraction. This space is inherently tied to the physical implementation of the memory system, including the capacity of memory chips and the interconnects like the memory bus.[7][8] The size of the physical address space is primarily determined by the width of the address bus, which specifies the number of bits available to represent addresses. For instance, an n-bit address bus allows the system to address up to 2^n unique locations, typically in bytes. In 64-bit systems like x86-64, the theoretical maximum is 2^64 bytes (approximately 16 exabytes), but practical implementations are limited by hardware design; most current x86-64 processors support up to 52 bits for physical addresses, enabling a maximum of 2^52 bytes (4 petabytes).[15][16] Hardware constraints often restrict the physical address space below theoretical limits, such as chip capacity or bus architecture, necessitating techniques like bank switching or memory mapping to expand access. Bank switching divides the memory into fixed-size banks that can be selectively mapped into the addressable range, allowing systems to access more total memory than the native bus width permits by swapping banks via hardware registers or latches. For example, early 8-bit processors, such as those using the Z80, which commonly featured a 16-bit address bus despite their data width, were limited to a maximum physical address space of 64 KB (2^16 bytes); bank switching was employed in some Z80-based systems to extend effective memory access beyond 64 KB. In contrast, the Intel 8086, a 16-bit processor, used segmented addressing with a 20-bit effective address bus to access up to 1 MB.[17] The CPU interacts with the physical address space through direct addressing, where memory operations use these raw physical addresses to read from or write to hardware locations without translation. This direct access ensures low-latency performance but makes the space vulnerable to fragmentation in multi-process environments, as contiguous blocks allocated to different processes can become scattered over time due to repeated allocations and deallocations.[18]Virtual Address Space

A virtual address space is an abstraction provided by the operating system to each process, creating the illusion of a large, contiguous, and private block of memory that appears dedicated solely to that process, regardless of the underlying physical memory configuration. This concept enables processes to operate as if they have exclusive access to a vast memory region, while the system maps these virtual addresses to actual physical locations as needed. The idea originated in the Multics operating system, where it was implemented to support efficient sharing of resources among multiple users in a time-sharing environment.[19] It was further popularized in Unix systems, particularly through the adoption of paging mechanisms in Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) releases starting in the late 1970s. In typical implementations, the size of a virtual address space is determined by the processor's addressing capabilities: 232 bytes (4 GB) for 32-bit architectures and up to 264 bytes (16 exabytes) for 64-bit architectures, allocated independently to each process. This per-process allocation allows multiple processes to run concurrently, sharing the physical memory pool without direct interference, as the operating system manages the mappings dynamically. For instance, in a 64-bit system, each process can theoretically address petabytes of memory, though practical limits due to hardware and software constraints often reduce this to 48 bits or less for virtual addresses.[1][20] Key benefits of virtual address spaces include robust isolation, which prevents one process from accessing or corrupting the memory of another, thereby enhancing system security and reliability. Additionally, techniques like demand paging complement this abstraction by loading memory pages into physical RAM only upon access, reducing initial memory demands and allowing efficient use of secondary storage for less frequently used data. This combination supports multitasking environments where processes can exceed the available physical memory without immediate failure.[1][19] However, virtual address spaces have limitations, such as thrashing, which arises when the collective working sets—the actively referenced pages—of running processes surpass the physical RAM capacity, causing excessive page faults and swapping that degrade performance. The 32-bit virtual address space constraint, capping each process at 4 GB, also historically limited scalability, prompting innovations like Physical Address Extension (PAE) in x86 architectures to enable access to larger physical memory pools despite the virtual limit.[21][22]Address Mapping and Translation

Translation Mechanisms

In address translation, a virtual address (VA) is divided into two primary components: the virtual page number (VPN), which identifies the page in virtual memory, and the offset, which specifies the byte position within that page. The VPN is used to index a page table, retrieving the corresponding physical frame number (PFN) if the page is resident in physical memory; the physical address (PA) is then constructed by combining the PFN with the unchanged offset. This process enables the abstraction of a contiguous virtual address space mapped onto potentially non-contiguous physical memory locations.[23] The basic mapping can be expressed as: where , and a common page size is 4 KB (requiring a shift of 12 bits). This formula ensures that the offset aligns correctly within the physical frame, preserving the relative positioning of data.[24] Two primary mechanisms underpin address translation: paging and segmentation. Paging employs fixed-size units called pages, typically 4 KB, to divide both virtual and physical memory into uniform blocks, facilitating efficient allocation and reducing external fragmentation. In contrast, segmentation partitions memory into variable-sized segments that correspond to logical program units, such as code or data sections, allowing for more intuitive sharing and protection but potentially introducing internal fragmentation. Some systems, including x86 architectures, adopt a hybrid approach that combines segmentation for high-level logical division with paging for fine-grained physical mapping.[23][25] Protection is integral to the translation process, where hardware checks permissions associated with each page or segment entry—such as read, write, and execute rights—before granting access, thereby enforcing memory isolation between processes and preventing unauthorized modifications. Violations of these permissions trigger a protection fault, ensuring system security without compromising performance.[23]Hardware and Software Support

The Memory Management Unit (MMU) is a hardware component integrated into the CPU that performs real-time virtual-to-physical address translation during memory access operations.[26] It evolved from designs in the 1970s, notably in Digital Equipment Corporation's VAX systems, where the VAX-11/780 model, introduced in 1977, incorporated an MMU to support a 32-bit virtual address space of 4 GB, with a 29-bit physical address space allowing up to 512 MB of memory.[27] In modern processors like those based on x86 architecture, the MMU handles paging mechanisms by walking through hierarchical page tables to resolve translations, enforcing protection attributes such as read/write permissions and user/supervisor modes.[26] Page tables serve as the core data structures for address mapping, organized hierarchically to manage large address spaces efficiently. In the 32-bit x86 (IA-32) architecture, a two-level structure consists of page directory entries (PDEs) and page table entries (PTEs); PDEs point to page tables or map 4 MB pages, while PTEs map individual 4 KB pages, with each entry including bits for presence, accessed status, and protection.[26] For the 64-bit x86-64 (Intel 64) extension, a four-level hierarchy expands this capability: the Page Map Level 4 (PML4) table indexes to Page Directory Pointer Tables (PDPTs), which lead to Page Directories (PDs) and finally Page Tables (PTs), supporting up to 48-bit virtual addresses and page sizes of 4 KB, 2 MB, or 1 GB to accommodate expansive memory layouts. Later extensions, such as five-level paging introduced by Intel in 2017, support up to 57-bit virtual addresses (512 TiB) in compatible processors.[26][28] This multi-level design reduces memory overhead by allocating tables on demand and only for used address regions.[29] The Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) acts as a high-speed cache within the MMU to store recent address translations, minimizing the latency of full page table walks on every access. Implemented with associative mapping for rapid parallel lookups, TLBs typically achieve hit rates exceeding 95% in workloads with good locality, such as sequential memory accesses, though rates can drop in sparse or random patterns.[30] On x86 processors, the TLB miss penalty involves multiple memory references for page table traversal, often 10-100 cycles, underscoring its role in overall system performance.[26] Software support for address translation is primarily provided by the operating system kernel, which dynamically allocates and populates page tables to reflect process address spaces. In systems like Linux, the kernel maintains a multi-level page table hierarchy (e.g., PGD, PUD, PMD, PTE) and updates entries during memory allocation or context switches.[29] When the MMU encounters an unmapped or protected access, it triggers a page fault interrupt, which the kernel handles via dedicated routines such asdo_page_fault() on x86; the handler resolves the fault by allocating pages, updating tables, or signaling errors like segmentation faults to the process.[29] This software-hardware interplay ensures efficient fault resolution while maintaining isolation between processes.[29]