Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Adjunct (grammar)

View on Wikipedia| Grammatical features |

|---|

In linguistics, an adjunct is an optional, or structurally dispensable, part of a sentence, clause, or phrase that, if removed or discarded, will not structurally affect the remainder of the sentence. Example: In the sentence John helped Bill in Central Park, the phrase in Central Park is an adjunct.[1]

A more detailed definition of the adjunct emphasizes its attribute as a modifying form, word, or phrase that depends on another form, word, or phrase, being an element of clause structure with adverbial function.[2] An adjunct is not an argument (nor is it a predicative expression), and an argument is not an adjunct. The argument–adjunct distinction is central in most theories of syntax and semantics. The terminology used to denote arguments and adjuncts can vary depending on the theory at hand. Some dependency grammars, for instance, employ the term circonstant (instead of adjunct), following Tesnière (1959).

The area of grammar that explores the nature of predicates, their arguments, and adjuncts is called valency theory. Predicates have valency; they determine the number and type of arguments that can or must appear in their environment. The valency of predicates is also investigated in terms of subcategorization.

Examples

[edit]Take the sentence John helped Bill in Central Park on Sunday as an example:

- John is the subject argument.

- helped is the predicator.

- Bill is the object argument.

- in Central Park is the first adjunct.

- on Sunday is the second adjunct.[1]

An adverbial adjunct is a sentence element that often establishes the circumstances in which the action or state expressed by the verb takes place. The following sentence uses adjuncts of time and place:

- Yesterday, Lorna saw the dog in the garden.

Notice that this example is ambiguous between whether the adjunct in the garden modifies the verb saw (in which case it is Lorna who saw the dog while she was in the garden) or the noun phrase the dog (in which case it is the dog who is in the garden). The definition can be extended to include adjuncts that modify nouns or other parts of speech (see noun adjunct).

Forms and domains

[edit]An adjunct can be a single word, a phrase, or an entire clause.[3]

- Single word

- She will leave tomorrow.

- Phrase

- She will leave in the morning.

- Clause

- She will leave after she has had breakfast.

Most discussions of adjuncts focus on adverbial adjuncts, that is, on adjuncts that modify verbs, verb phrases, or entire clauses like the adjuncts in the three examples just given. Adjuncts can appear in other domains, however; that is, they can modify most categories. An adnominal adjunct is one that modifies a noun: for a list of possible types of these, see Components of noun phrases. Adjuncts that modify adjectives and adverbs are occasionally called adadjectival and adadverbial.

- the discussion before the game – before the game is an adnominal adjunct.

- very happy – very is an "adadjectival" adjunct.

- too loudly – too is an "adadverbial" adjunct.

Adjuncts are always constituents. Each of the adjuncts in the examples throughout this article is a constituent.

Semantic function

[edit]Adjuncts can be categorized in terms of the functional meaning that they contribute to the phrase, clause, or sentence in which they appear. The following list of the semantic functions is by no means exhaustive, but it does include most of the semantic functions of adjuncts identified in the literature on adjuncts:[4]

- Causal – Causal adjuncts establish the reason for, or purpose of, an action or state.

- The ladder collapsed because it was old. (reason)

- Causal – Causal adjuncts establish the reason for, or purpose of, an action or state.

- Concessive – Concessive adjuncts establish contrary circumstances.

- Lorna went out although it was raining.

- Concessive – Concessive adjuncts establish contrary circumstances.

- Conditional – Conditional adjuncts establish the condition in which an action occurs or state holds.

- I would go to Paris, if I had the money.

- Conditional – Conditional adjuncts establish the condition in which an action occurs or state holds.

- Consecutive – Consecutive adjuncts establish an effect or result.

- It rained so hard that the streets flooded.

- Consecutive – Consecutive adjuncts establish an effect or result.

- Final – Final adjuncts establish the goal of an action (what one wants to accomplish).

- He works a lot to earn money for school.

- Final – Final adjuncts establish the goal of an action (what one wants to accomplish).

- Instrumental – Instrumental adjuncts establish the instrument used to accomplish an action.

- Mr. Bibby wrote the letter with a pencil.

- Instrumental – Instrumental adjuncts establish the instrument used to accomplish an action.

- Locative – Locative adjuncts establish where, to where, or from where a state or action happened or existed.

- She sat on the table.

- Locative – Locative adjuncts establish where, to where, or from where a state or action happened or existed.

- Measure – Measure adjuncts establish the measure of the action, state, or quality that they modify

- I am completely finished.

- That is mostly true.

- We want to stay in part.

- Measure – Measure adjuncts establish the measure of the action, state, or quality that they modify

- Modal – Modal adjuncts establish the extent to which the speaker views the action or state as (im)probable.

- They probably left.

- In any case, we didn't do it.

- That is perhaps possible.

- I'm definitely going to the party.

- Modal – Modal adjuncts establish the extent to which the speaker views the action or state as (im)probable.

- Modificative – Modificative adjuncts establish how the action happened or the state existed.

- He ran with difficulty. (manner)

- He stood in silence. (state)

- He helped me with my homework. (limiting)

- Modificative – Modificative adjuncts establish how the action happened or the state existed.

- Temporal – Temporal adjuncts establish when, how long, or how frequent the action or state happened or existed.

- He arrived yesterday. (time point)

- He stayed for two weeks. (duration)

- She drinks in that bar every day. (frequency)

- Temporal – Temporal adjuncts establish when, how long, or how frequent the action or state happened or existed.

Distinguishing between predicative expressions, arguments, and adjuncts

[edit]Omission diagnostic

[edit]The distinction between arguments and adjuncts and predicates is central to most theories of syntax and grammar. Predicates take arguments and they permit (certain) adjuncts.[5] The arguments of a predicate are necessary to complete the meaning of the predicate.[6] The adjuncts of a predicate, in contrast, provide auxiliary information about the core predicate-argument meaning, which means they are not necessary to complete the meaning of the predicate. Adjuncts and arguments can be identified using various diagnostics. The omission diagnostic, for instance, helps identify many arguments and thus many possible adjuncts as well. If a given constituent cannot be omitted from a sentence, clause, or phrase without resulting in an unacceptable expression, that constituent is not an adjunct. In contrast, if a given constituent can be omitted without affecting grammaticality or core meaning, that constituent is an adjunct. E.g.:

- a. Fred certainly knows.

- b. Fred knows. – certainly may be an adjunct (and it is).

- a. He stayed after class.

- b. He stayed. – after class may be an adjunct (and it is).

- a. I know her.

- b. I know. - the sentence is acceptable, but its meaning is changed entirely. Therefore her is not an adjunct.

- a. She trimmed the bushes.

- b. *She trimmed. – the bushes is not an adjunct.

- a. Jim stopped.

- b. *Stopped. – Jim is not an adjunct.

Other diagnostics

[edit]Further diagnostics used to distinguish between arguments and adjuncts include multiplicity, distance from head, and the ability to coordinate. A head can have multiple adjuncts but only one object argument (=complement):

- a. Bob ate the pizza. – the pizza is an object argument (=complement).

- b. Bob ate the pizza and the hamburger. the pizza and the hamburger is a noun phrase that functions as object argument.

- c. Bob ate the pizza with a fork. – with a fork is an adjunct.

- d. Bob ate the pizza with a fork on Tuesday. – with a fork and on Tuesday are both adjuncts.

Object arguments are typically closer to their head than adjuncts:

- a. the collection of figurines (complement) in the dining room (adjunct)

- b. *the collection in the dining room (adjunct) of figurines (complement)

Adjuncts can be coordinated with other adjuncts, but not with arguments:

- a. *Bob ate the pizza and with a fork.

- b. Bob ate with a fork and with a spoon.

Optional arguments vs. adjuncts

[edit]The distinction between arguments and adjuncts is much less clear than the simple omission diagnostic (and the other diagnostics) suggests. Most accounts of the argument vs. adjunct distinction acknowledge a further division. One distinguishes between obligatory and optional arguments. Optional arguments pattern like adjuncts when just the omission diagnostic is employed, e.g.

- a. Fred ate a hamburger.

- b. Fred ate. – a hamburger is not an obligatory argument, but it could be (and it is) an optional argument.

- a. Sam helped us.

- b. Sam helped – us is not an obligatory argument, but it could be (and it is) an optional argument.

The existence of optional arguments blurs the line between arguments and adjuncts considerably. Further diagnostics (beyond the omission diagnostic and the others mentioned above) must be employed to distinguish between adjuncts and optional arguments. One such diagnostic is the relative clause test. The test constituent is moved from the matrix clause to a subordinate relative clause containing which occurred/happened. If the result is unacceptable, the test constituent is probably not an adjunct:

- a. Fred ate a hamburger.

- b. Fred ate. – a hamburger is not an obligatory argument.

- c. *Fred ate, which occurred a hamburger. – a hamburger is not an adjunct, which means it must be an optional argument.

- a. Sam helped us.

- b. Sam helped. – us is not an obligatory argument.

- c. *Sam helped, which occurred us. – us is not an adjunct, which means it must be an optional argument.

The particular merit of the relative clause test is its ability to distinguish between many argument and adjunct PPs, e.g.

- a. We are working on the problem.

- b. We are working.

- c. *We are working, which is occurring on the problem. – on the problem is an optional argument.

- a. They spoke to the class.

- b. They spoke.

- c. *They spoke, which occurred to the class. – to the class is an optional argument.

The reliability of the relative clause diagnostic is actually limited. For instance, it incorrectly suggests that many modal and manner adjuncts are arguments. This fact bears witness to the difficulty of providing an absolute diagnostic for the distinctions currently being examined. Despite the difficulties, most theories of syntax and grammar distinguish on the one hand between arguments and adjuncts and on the other hand between optional arguments and adjuncts, and they grant a central position to these divisions in the overarching theory.

Predicates vs. adjuncts

[edit]Many phrases have the outward appearance of an adjunct but are in fact (part of) a predicate instead. The confusion occurs often with copular verbs, in particular with a form of be, e.g.

- It is under the bush.

- The party is at seven o'clock.

The PPs in these sentences are neither adjuncts nor arguments. The preposition in each case is, rather, part of the main predicate. The matrix predicate in the first sentence is is under; this predicate takes the two arguments It and the bush. Similarly, the matrix predicate in the second sentence is is at; this predicate takes the two arguments The party and seven o'clock. Distinguishing between predicates, arguments, and adjuncts becomes particularly difficult when secondary predicates are involved, for instance with resultative predicates, e.g.

- That made him tired.

The resultative adjective tired can be viewed as an argument of the matrix predicate made. But it is also definitely a predicate over him. Such examples illustrate that distinguishing predicates, arguments, and adjuncts can become difficult and there are many cases where a given expression functions in more ways than one.

Overview

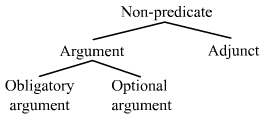

[edit]The following overview is a breakdown of the current divisions:

This overview acknowledges three types of entities: predicates, arguments, and adjuncts, whereby arguments are further divided into obligatory and optional ones.

Representing adjuncts

[edit]Many theories of syntax and grammar employ trees to represent the structure of sentences. Various conventions are used to distinguish between arguments and adjuncts in these trees. In phrase structure grammars, many adjuncts are distinguished from arguments insofar as the adjuncts of a head predicate will appear higher in the structure than the object argument(s) of that predicate. The adjunct is adjoined to a projection of the head predicate above and to the right of the object argument, e.g.

The object argument each time is identified insofar as it is a sister of V that appears to the right of V, and the adjunct status of the adverb early and the PP before class is seen in the higher position to the right of and above the object argument. Other adjuncts, in contrast, are assumed to adjoin to a position that is between the subject argument and the head predicate or above and to the left of the subject argument, e.g.

The subject is identified as an argument insofar as it appears as a sister and to the left of V(P). The modal adverb certainly is shown as an adjunct insofar as it adjoins to an intermediate projection of V or to a projection of S. In X-bar theory, adjuncts are represented as elements that are sisters to X' levels and daughters of X' level [X' adjunct [X'...]].

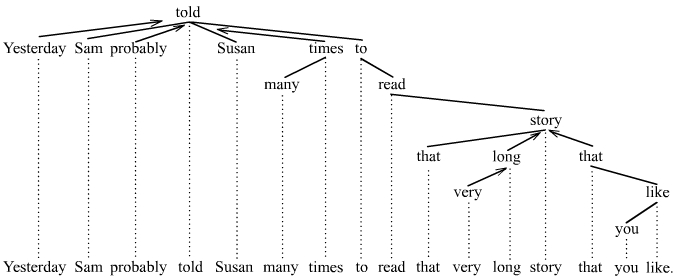

Theories that assume sentence structure to be less layered than the analyses just given sometimes employ a special convention to distinguish adjuncts from arguments. Some dependency grammars, for instance, use an arrow dependency edge to mark adjuncts,[7] e.g.

The arrow dependency edge points away from the adjunct toward the governor of the adjunct. The arrows identify six adjuncts: Yesterday, probably, many times, very, very long, and that you like. The standard, non-arrow dependency edges identify Sam, Susan, that very long story that you like, etc. as arguments (of one of the predicates in the sentence).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b See Lyons (1968).

- ^ "Adjunct - Define Adjunct at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com.

- ^ Briggs, Thomas Henry; Isabel McKinney; Florence Vane Skeffington (1921). "DISTINGUISHING PHRASE AND CLAUSE ADJUNCTS". Junior high school English, Book 2. Boston, MA, USA: Ginn and company. pp. 116.

- ^ For similar inventories of adjunct functions, see Payne (2006:298).

- ^ Concerning the distinction between arguments and adjuncts, see Payne (2006:297).

- ^ See Payne (2006:107ff.).

- ^ For an example of the arrow used to mark adjuncts, see for instance Eroms (2000).

References

[edit]- Eroms, H.-W. 2000. Syntax der deutschen Sprache. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Carnie, A. 2010. Constituent Structure. Oxford: Oxford U.P.

- Lyons J. 1968. Introduction to theoretical linguistics. London: Cambridge U.P.

- Payne, T. 2006. Exploring language structure: A student's guide. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Tesnière, L. 1959. Éleménts de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck.

Adjunct (grammar)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

In linguistics, an adjunct is defined as an optional syntactic element that modifies or adds information to a phrase, clause, or sentence without being required for its grammatical completeness or well-formedness.[3][4] Unlike core components, an adjunct can be omitted without rendering the construction ungrammatical or semantically incomplete, as it is syntactically parasitic on a fully formed host constituent.[4] The term derives from the Latin adjunctus, the past participle of adiungere ("to join to" or "to attach"), from ad- ("to") + iungere ("to join"), emphasizing its role as an additive, supplementary element.[5] Adjuncts contrast with obligatory elements such as subjects and objects, which form part of the predicate's valence—the set of arguments required by a verb or head to satisfy its subcategorization frame in valency theory.[6][3] In this framework, pioneered by Lucien Tesnière, valence specifies the number and type of complements needed for completeness, whereas adjuncts are non-selected and do not contribute to fulfilling these requirements.[6] For instance, in valency grammar, arguments like direct objects are integral to the verb's lexical properties, while adjuncts provide peripheral modifications such as manner or location. Key characteristics of adjuncts include their modificational function, often adverbial or adjectival in nature, whereby they elaborate on aspects like time, place, or reason without altering the core syntactic category of the host.[4] They typically appear as phrases, such as prepositional phrases (e.g., in the park), adverb phrases (e.g., quickly), or subordinate clauses (e.g., while reading), and are not theta-role assigned by the verb in the same obligatory manner as arguments.[3] This optional, endocentric quality allows adjuncts to stack or iterate freely in many languages, enhancing descriptive detail.[3]Basic Examples

Adjuncts, as optional modifiers that add circumstantial information to a clause, are exemplified in basic English sentences. In "She left in a hurry," the prepositional phrase "in a hurry" functions as a manner adjunct, describing the way in which the leaving occurred.[1] Similarly, in "We met yesterday," the adverb "yesterday" acts as a time adjunct, specifying the temporal context of the meeting.[1] Another instance is "He runs in the park," where "in the park" serves as a location adjunct, indicating the spatial setting of the action.[1] A defining feature of adjuncts is their dispensability: omitting them yields a complete, grammatical sentence that retains its essential meaning. Thus, "She left," "We met," and "He runs" stand alone as valid propositions, with the adjuncts merely providing supplementary details.[1] These elements play a crucial role in enriching sentence description by layering additional context—such as how, when, or where an event unfolds—without changing the fundamental assertion of the clause.[1] The phenomenon extends cross-linguistically. In Latin, "Puella in villa cantat" ("The girl sings in the villa") employs "in villa" as a locative adjunct via the prepositional phrase.[7] Likewise, in Mandarin Chinese, "Tā mǎshàng zǒu le" ("He left immediately") uses the adverb "mǎshàng" as an adjunct conveying immediacy or manner.[8]Forms and Types

Syntactic Forms

Adjuncts manifest in a variety of syntactic forms, primarily as optional modifiers that attach to phrases without fulfilling obligatory argument roles. Common realizations include prepositional phrases (PPs), adverb phrases (AdvPs), noun phrases (NPs), and subordinate clauses. For instance, PPs such as with enthusiasm typically express manner or means, while AdvPs like quickly convey similar information about how an action occurs. NPs functioning as adjuncts, such as last week, often denote time or frequency, and subordinate clauses like because it rained provide causal or conditional modification.[1] Within sentences, adjuncts occupy distinct positions that influence their integration into the clause structure. In English, adjuncts frequently appear in final position as the default placement after the verb phrase (VP), as in She left yesterday. They may also occur in initial position through fronting for emphasis or discourse purposes, yielding Yesterday, she left. Medial positions, embedded within the VP or between auxiliaries and the main verb, are possible for certain adjuncts, particularly adverbs, as in She has quickly finished her work. These positional options allow flexibility while maintaining syntactic well-formedness.[9][10] When multiple adjuncts co-occur, they can stack in sequence, adhering to a hierarchical order governed by scope relations, where adjuncts with narrower scope typically precede those with broader scope in final position. In English, this results in a common sequence of manner before place before time, as exemplified in She painted the room carefully in the attic last summer, where the temporal adjunct last summer scopes over the locative in the attic and manner carefully. This ordering reflects c-command relations among adjuncts, ensuring interpretative coherence.[11] Cross-linguistically, adjunct placement varies with basic word order. In verb-final languages like Japanese, adjuncts generally precede the verb to align with the head-final structure, as in constructions where temporal or manner modifiers appear before the main predicate, such as Kinō hayaku hashitta ('Yesterday quickly ran'). This preverbal positioning contrasts with the postverbal defaults in English but maintains the adjunct's modificational role relative to the VP.[12][13]Semantic Types

Adjuncts in grammar are classified semantically according to the type of information they provide, such as temporal, locative, manner, reason, or conditional details, which help specify circumstances surrounding the core event or proposition.[14] These categories reflect the interpretive roles adjuncts play in enriching sentence meaning without being obligatory arguments.[15] Temporal adjuncts indicate when an event occurs, such as "at noon" in "The meeting starts at noon," providing chronological context to the verb phrase.[14] Locative adjuncts specify location, as in "in Paris" from "She lives in Paris," denoting spatial position relative to the action.[15] Manner adjuncts describe how an action is performed, exemplified by "carefully" in "He painted the wall carefully," focusing on the method or style.[14] Reason adjuncts explain causation or motivation, like "due to illness" in "She missed the class due to illness."[14] Conditional adjuncts express hypothetical circumstances, such as "if possible" in "We will proceed if possible."[14] Within these, instrumentals and comitatives form notable subtypes. Instrumentals denote tools or means used in an action, as in "with a knife" from "She cut the bread with a knife."[14] Comitatives indicate accompaniment, such as "with friends" in "She traveled with friends," highlighting shared participation.[14] These subtypes often overlap with broader categories like manner or locative but emphasize specific relational aspects.[14] Scope effects arise in how adjuncts interact with sentence elements, potentially modifying the entire clause for broad applicability or targeting specific arguments for narrower focus.[16] For instance, an adverb like "again" in "Leslie opened the door again" can scope over the whole event (repetitive action) or sublexically over a particular argument (restitution of state), allowing flexible interpretations based on context.[16] This underspecification in semantic representation enables adjuncts to adapt without rigid syntactic constraints.[16] Cross-linguistically, languages vary in encoding these semantic types, with some requiring obligatory marking for spatial adjuncts through morphological cases. In Finnish, for example, cases like inessive ("in the house") and adessive ("at the house") obligatorily express locative relations, integrating what English treats as optional prepositional phrases directly into noun morphology.[17] Similarly, instrumental cases in such languages mark means or accompaniment, contrasting with analytic constructions in English.[17] These differences highlight how semantic adjunct functions can be grammaticalized variably across languages.[17]Distinguishing Adjuncts

From Arguments and Complements

In linguistics, arguments are syntactic elements that fill specific theta roles essential to the verb's core meaning, such as agent, theme, or goal, which are lexically specified by the verb through its subcategorization frame.[18] For example, in the sentence "She gave [a book] [to her friend]," "a book" serves as the theme argument and "to her friend" as the goal argument, both required to complete the event described by the ditransitive verb "give."[19] These roles are semantically obligatory, reflecting the verb's valency—the fixed number of arguments it demands to form a complete predicate.[18] Complements, often overlapping with arguments in verbal contexts, function as obligatory modifiers that satisfy the head's selectional restrictions, integrating semantically with the predicate to form a unified property.[20] For instance, in "She is proud [of her achievement]," the prepositional phrase "of her achievement" acts as a complement to the adjective "proud," required by its subcategorization and imposing restrictions that the complement denote something praiseworthy.[20] Unlike free modifiers, complements cannot be omitted without rendering the construction incomplete or semantically anomalous, as they contribute directly to the predicate's interpretation.[19] Adjuncts, by contrast, are optional elements that do not fill subcategorized theta roles or satisfy the verb's selectional restrictions, instead adding supplementary information such as manner, location, or time without altering the core event structure.[18] They attach at a higher structural level, external to the verb's argument structure, and can often be iterated or reordered relative to the predicate without affecting grammaticality.[20] Consider the verb "eat," which subcategorizes for an optional theme argument but not a location; thus, "She ate [an apple]" features "an apple" as an argument fulfilling the theme role, whereas "She ate [in the kitchen]" treats "in the kitchen" as an adjunct providing circumstantial detail that can be freely added or removed.[19] This distinction highlights valency reduction in argument structure: verbs possess a predetermined set of argument slots defined by their lexical properties, while adjuncts introduce additional layers of modification that expand the sentence beyond the minimal predicate.[18] For example, the transitive verb "devour" requires a theme like "the cake" to saturate its valency, but phrases like "quickly" or "at midnight" function as adjuncts, enhancing but not completing the verb's semantic requirements.[20] Such criteria ensure that adjuncts remain structurally and semantically peripheral to the verb's obligatory frame.From Predicates and Predicatives

In grammatical analysis, the predicate constitutes the core element of a clause that asserts a primary property or relation about the subject, typically comprising the main verb phrase along with its obligatory arguments and certain integrated modifiers. Adjuncts, however, attach externally to this predicate structure, providing supplementary information without contributing to its essential assertion; they are optional and can be omitted without rendering the predication incomplete. For example, in the sentence She runs in the park, the predicate is the verb phrase runs, while in the park functions as a locative adjunct modifying the circumstances of the action rather than forming part of the core predication. Predicatives, on the other hand, are expressions that attribute a quality, class, or state to a subject or object, often appearing in copular constructions with verbs like be, seem, or become. Predicative complements are licensed directly by the verb as part of the nuclear predication and can take various forms, including prepositional phrases, such as in the room in She is in the room, where it serves as a required complement ascribing a location to the subject. In contrast, true adjuncts add optional circumstantial detail externally to the predication; for example, in She is in the room today, today functions as a temporal adjunct that can be fronted (Today, she is in the room) or omitted (She is in the room) with minimal impact on the clause's grammaticality. A key distinction arises in edge cases involving secondary predication, where an additional predicative element attributes a property to an argument of the main verb, often in resultative or depictive constructions. For instance, in They left the door open, open serves as a secondary predicate ascribing a resulting state to the door (an object of the main verb left), yet it attaches syntactically as an adjunct to the primary predication rather than as an integrated complement. Similarly, depictive secondary predicates like raw in She ate the meat raw describe a concurrent property of the object during the event, forming a thematic relation but remaining external to the core predicate structure; this contrasts with non-predicational adjuncts, such as manner adverbs, which do not assign properties to specific arguments. These secondary predications highlight the boundary where adjunct status coexists with predicative function, always treating the secondary element as optional and non-essential to the main clause's assertion.[21][22]Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic tests provide empirical methods to distinguish adjuncts from arguments and complements in syntactic analysis, relying on properties like optionality, mobility, and compatibility in constructions. These tests are not infallible individually, as some phrases may yield mixed results, but they converge to identify adjuncts as syntactically optional elements that add circumstantial information without fulfilling a verb's subcategorization requirements.[18][23] The omission test, also known as the optionality test, determines whether a phrase can be removed from the sentence while preserving grammaticality and core propositional meaning. Adjuncts pass this test, as their deletion yields a well-formed sentence; for example, in "She sang beautifully in the garden," omitting "beautifully" or "in the garden" results in "She sang," which remains grammatical. In contrast, arguments typically fail, as in "*John devoured," where the direct object is required. This test highlights adjuncts' non-essential status, though exceptions like obligatory adjuncts (e.g., certain locatives) require corroboration with other diagnostics.[23][24] The movement test assesses whether a phrase can be displaced, such as by fronting to sentence-initial position, without inducing ill-formedness or semantic anomaly. Adjuncts generally permit this, as seen in "[Yesterday], we met in the park," where "yesterday" or "in the park" moves freely as a topicalized adjunct. Arguments resist such movement; for instance, fronting the object in "*The book, John read yesterday" is awkward unless focused. This mobility reflects adjuncts' peripheral attachment in the syntactic structure, allowing flexible positioning relative to the verb phrase.[20][25] The coordination test evaluates whether a phrase can be conjoined with another using "and," revealing category compatibility. Adjuncts coordinate readily with other adjuncts but not with arguments; for example, "She arrived early and quietly" links two manner adjuncts successfully, while "*John gave the gift to Mary and yesterday" fails because "to Mary" (argument) mismatches "yesterday" (adjunct). This test underscores adjuncts' shared modifier status, distinct from the theta-role satisfaction of arguments.[20][23] Distinguishing truly optional adjuncts from pseudo-optional arguments involves verbs where a phrase appears dispensable but actually subcategorizes as an argument, such as prepositional phrases with verbs like "discuss." In "They discussed the issue," omitting "the issue" yields "They discussed," which seems grammatical but semantically incomplete, as "discuss" selects an aboutness argument; true adjuncts like "yesterday" omit cleanly without such gaps. Verb specificity aids resolution: arguments are tied to particular lexical items, whereas adjuncts are more general.[23] Additional diagnostics include do-support insensitivity, observed in pseudocleft and VP-anaphora constructions where adjuncts integrate without triggering auxiliary support changes. For instance, in the pseudocleft "What John did yesterday was eat the cake," "yesterday" follows "did" as an adjunct, unlike arguments that precede it; similarly, "Bill ate the apple quickly, and John did so slowly" allows adjunct iteration with "do so." Scope ambiguity resolution further aids identification: adjuncts often permit wider scopal readings in ambiguous sentences, such as quantifier interactions, where processing heuristics favor argument interpretations first, resolving to adjunct status if ambiguities persist (e.g., "Every student read a book in the library" allowing library-scope over every). These tests collectively reinforce adjuncts' syntactic independence.[23][18]Semantic Roles

Core Functions

Adjuncts enrich the propositional content of a sentence by incorporating optional descriptive elements that specify circumstances surrounding the core event, such as manner, time, or location, thereby providing additional layers of meaning without altering the fundamental truth conditions defined by the verb and its arguments.[26] This process typically occurs through predicate modification, where the adjunct's semantic contribution conjoins with the main predicate to form a unified denotation; for instance, in "She sang beautifully in the garden," the adjuncts "beautifully" and "in the garden" add details to the proposition "She sang" but do not change its basic verifiability.[26] Such enrichment enhances the informativeness of the utterance while preserving the sentence's grammatical integrity if the adjuncts are omitted. In discourse, adjuncts fulfill key structuring roles, with their positioning influencing how information is organized and interpreted. Initial adjuncts often function to set the topic or establish a frame for the subsequent clause, orienting the listener to the contextual backdrop; for example, "Yesterday, the team won the match" uses "yesterday" to anchor the event temporally at the discourse outset.[27] Conversely, final adjuncts typically background details, presenting them as secondary or supportive to the main assertion, as in "The team won the match yesterday," where the time adjunct recedes into the periphery to emphasize the victory.[27] These positional effects contribute to discourse coherence by signaling prominence or subordination without impacting the clause's core propositional structure. Certain adjuncts express politeness, evidentiality, or the speaker's subjective attitude toward the proposition, operating outside the strict truth-conditional domain. Evaluative adverbs like "fortunately" or "regrettably" serve as disjuncts that comment on the desirability or speaker's perspective of the event, as in "Fortunately, the team won the match," where "fortunately" conveys relief or positive stance without asserting factual content. Similarly, evidential adjuncts such as "allegedly" indicate the source of information or degree of commitment, enriching the utterance with metalinguistic nuance while remaining detachable.[26] A notable constraint on adjuncts is their inability to introduce new discourse referents, distinguishing them sharply from arguments that saturate the predicate's valency and bring entities into focus.[26] For example, while an argument like the subject in "The cat scratched the mouse" introduces "the cat" and "the mouse" as active participants, an adjunct such as "with its claws" modifies the action but presupposes existing referents without adding novel ones to the discourse model.[26] This limitation ensures adjuncts remain modifiers rather than essential saturators, reinforcing their optional status in sentence construction.Interaction with Sentence Meaning

Adjuncts interact with sentence meaning by introducing scope ambiguities, particularly when focus-sensitive particles like only associate with different elements in the clause. For instance, in the sentence "She only ate in the kitchen," only can associate with the verb ate, implying that eating was the sole activity performed in the kitchen, or with the prepositional phrase (PP) "in the kitchen," restricting the location of eating to that specific place. This ambiguity arises because only seeks the highest syntactic domain it c-commands for focus association, potentially pulling the PP adjunct into its scope and altering the propositional content. Experimental evidence shows that positioning only before the main verb increases preferences for high attachment interpretations of temporal or locative PPs, shifting meanings by over 30% compared to low attachment scenarios.[28] Such interactions highlight how adjuncts can dynamically constrain alternatives in the sentence's semantic representation, affecting overall truth conditions without changing syntactic structure.[29] In terms of compositionality, adjuncts function as semantic operators that adjust the meaning of the verb phrase through incremental modification, preserving the principle that complex meanings derive from simpler components. The adverb again, for example, serves as a single lexical operator (ω(L)*) that concatenates with the event predicate, yielding either iterative (repetitive) or restitutive readings depending on aspectual viewpoint. In "John opened the door again," an iterative reading implies repetition of the full event (John opened it before), while a restitutive reading focuses on restoring a prior result state (the door was open previously, regardless of cause). These interpretations emerge compositionally without lexical ambiguity, as again applies before or after the phase transition in the event structure, influenced by intonation: stress on the object favors restitutive ("John opened the DOOR again"), while stress on again favors iterative ("John opened the door AGAIN"). This operator-like behavior ensures that adjuncts contribute to sentence meaning predictably, enabling flexible yet principled semantic integration.[30] Adjuncts further modify event structure by framing aspectual properties, such as duration, which influences the telicity and boundedness of the described event. Durative adjuncts like "for hours" adjoin to the verb phrase (VP), specifying the internal temporal extent of an atelic event without imposing an endpoint, as in "She read for hours." This contrasts with time-frame adjuncts (e.g., "in two hours"), which adjoin higher to the aspectual phrase (AspP) and delimit a telic event's completion time. In bounded events, where a definite endpoint is encoded in AspP (e.g., via a direct object or resultative PP), durative adjuncts measure the duration up to that boundary, enhancing the event's semantic profile without altering its core argument structure. Syntactically, this low attachment to VP explains why duratives are incompatible with certain extractions or scope shifts that target higher projections.[31] Cross-linguistically, adjuncts exhibit semantic shifts that can imply causation or purpose, varying based on how directional PPs integrate with verb semantics. In English, a satellite-framed language, manner verbs like run combine freely with goal adjuncts such as "to the store" in "She ran to the store," implying directed motion toward a purpose that evokes a causal path to completion. In contrast, verb-framed languages like Spanish disallow this construction (Juan corrió a la tienda), requiring path encoding in the verb (e.g., Juan entró corriendo), which shifts the causal implication to the lexical verb rather than the adjunct. Similarly, languages like Korean permit resultative constructions implying causation (e.g., pounding something flat) but restrict manner-plus-direction combinations, while equipollently framed languages like Japanese allow both but vary in adjunct integration. These microparametric differences demonstrate how adjuncts can enrich or constrain causative inferences across languages, affecting event telicity without universal uniformity.[32]Theoretical Representation

In Generative Grammar

In generative grammar, the treatment of adjuncts has evolved significantly since the inception of transformational grammar. Early formulations, as outlined in Chomsky's foundational works, distinguished adjuncts from obligatory arguments through optional transformations or phrase structure rules that permitted their insertion without selectional restrictions. By the 1970s, with the advent of X-bar theory, adjuncts were formalized as optional sisters to intermediate projections (X'), allowing recursive modification while preserving endocentricity.[33] This development continued into the Government and Binding framework of the 1980s, where adjuncts were integrated into principle-based constraints, emphasizing their non-theta-marked status and freedom from subcategorization.[34] In contemporary phase-based models within the minimalist program, adjuncts are derived through simplified operations that align with economy principles, often attaching within or across phases without disrupting core computational processes.[35] Within X-bar theory, adjuncts occupy dedicated positions by adjoining to an intermediate bar-level projection, such as an adverbial phrase (AdvP) attaching to VP, forming a higher XP while inheriting the category label from the host phrase. For instance, in a structure like [VP [V' [V sang] [AdvP quickly]], the AdvP adjoins to V', resulting in a V'' that projects the V-head's features upward.[36] This adjunction mechanism, pioneered by Jackendoff, ensures adjuncts modify without altering the argument structure, distinguishing them from specifiers (which target XP) or complements (sisters to X0).[33] Unlike arguments, adjuncts do not saturate valency, allowing multiple layers of attachment, as seen in recursive adverbials like "She sang beautifully and confidently." In the minimalist program, adjunct attachment primarily involves external Merge, combining a new syntactic object (the adjunct) with an existing phrase from the numeration, contrasting with internal Merge used for movement operations like wh-extraction.[35] Chomsky proposes that such adjunctions form unlabeled or pair-merge structures, avoiding the need for complex labeling algorithms and ensuring adjuncts integrate seamlessly without theta-role assignment.[37] This external attachment preserves the host's label, as in merging an AdvP externally to a vP phase, facilitating late insertion in derivations while adhering to the no-tampering condition.[35] Internal Merge may apply in cases of adjunct remerge, such as scope-related displacements, but adjuncts fundamentally rely on external operations for base generation.[38] Regarding feature percolation, adjuncts typically do not initiate feature transmission but inherit percolated features from the host head via upward projection, bypassing theta-grid involvement since they lack selectional properties. In early X-bar implementations, features from the lexical head (e.g., verbal tense) percolate through the adjunction site to the maximal projection, maintaining agreement uniformity. Travis's parameter-based approach highlights how directionality affects percolation in adjunct chains, with features flowing unidirectionally in head-initial languages.[39] In minimalist extensions, traditional percolation yields to local feature checking and Agree relations, where adjuncts probe uninterpretable features on the host without full percolation, optimizing computational efficiency in phase domains.[40] This shift ensures adjuncts contribute interpretively without overloading the feature system.[41]In Other Frameworks

In dependency grammar, adjuncts are represented as non-head dependents that attach loosely to a head without requiring subcategorization, allowing for flexible integration into the dependency tree via generic rules such asX → X Y {Y:fun = adjunct} or X → Y X {Y:fun = adjunct}.[42] This approach treats adjuncts as optional modifiers that augment the structure independently, contrasting with complements that complete the head's valence.[43] For instance, in a sentence like "John read the book in the library," the prepositional phrase "in the library" depends on the verb "read" as an adjunct, enabling multiple attachment points without disrupting projectivity.[42]

In functional grammars, such as Role and Reference Grammar (RRG), adjuncts function as satellites that modify elements at specific layers of the clause structure—nucleus, core, or clause—rather than as core arguments.[44] Nuclear adjuncts, like aspectual adverbs (e.g., "continuously"), attach to the predicate nucleus and often appear medially; core adjuncts, such as manner phrases (e.g., "carefully"), modify the predicate plus arguments and prefer final positions; while clause-level adjuncts, like epistemic modifiers (e.g., "probably"), scope over the entire clause.[44] This layered representation emphasizes the adjunct's role in enriching semantic information without altering argument structure, as seen in corpus analyses where positional preferences align with layer modification (e.g., 66% of nuclear adjuncts medial in technical texts).[44]

Categorial grammar models adjuncts as functors of the form X\X or X/X, which take a constituent of type X as argument and yield a modified X as result, thereby altering argument structures through composition.[45] For example, an adverb like "quickly" is categorized as ((S\NP)(S\NP)) / (S\NP), modifying a verb phrase by wrapping around it to add manner information without filling a valence slot.[45] This functor-based treatment ensures that adjuncts integrate seamlessly into derivations, preserving the grammar's type-theoretic constraints on syntax-semantics interface.[45]

Dependency models offer comparative advantages in handling free word order, particularly in adjunct-heavy languages like German, by decoupling syntactic dependencies from linear precedence through topological fields and flexible linearization rules.[46] In German, where adjuncts such as temporal or locative phrases can scramble freely within the Mittelfeld (e.g., over 30 permutations in complex clauses), dependency grammar avoids phrase-structure rigidity, treating all non-head dependents—including adjuncts—as reorderable within domains without invoking movement operations.[46] This facilitates parsing of surface variations while maintaining underlying relational integrity, outperforming hierarchical models in efficiency for such languages.[46]