Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Clusivity

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2025) |

| Grammatical features |

|---|

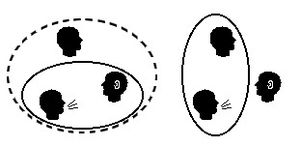

In linguistics, clusivity[1] is a grammatical distinction between inclusive and exclusive first-person pronouns and verbal morphology, also called inclusive "we" and exclusive "we". Inclusive "we" specifically includes the addressee, while exclusive "we" specifically excludes the addressee; in other words, two (or more) words that both translate to "we", one meaning "you and I, and possibly someone else", the other meaning "I and some other person or persons, but not you". While imagining that this sort of distinction could be made in other persons (particularly the second) is straightforward, in fact the existence of second-person clusivity (you vs. you and they) in natural languages is controversial and not well attested.[2] While clusivity is not a feature of the English language, it is found in many languages around the world.

The first published description of the inclusive-exclusive distinction by a European linguist was in a description of languages of Peru in 1560 by Domingo de Santo Tomás in his Grammatica o arte de la lengua general de los indios de los Reynos del Perú, published in Valladolid, Spain.[3]

Schematic paradigm

[edit]

Clusivity paradigms may be summarized as a two-by-two grid:

| Includes the addressee? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Includes the speaker? |

Yes | Inclusive we: I and you (and possibly they) |

Exclusive we: I and they, but not you |

| No | you / yous(e) / y'all | they | |

Morphology

[edit]In some languages, the three first-person pronouns appear to be unrelated roots. That is the case for Chechen, which has singular со (so), exclusive тхо (txo), and inclusive вай (vay). In others, however, all three are transparently simple compounds, as in Tok Pisin, an English creole spoken in Papua New Guinea, which has singular mi, exclusive mi-pela, and inclusive yu-mi (a compound of mi with yu "you") or yu-mi-pela. However, when only one of the plural pronouns is related to the singular, that may be the case for either one. In some dialects of Mandarin Chinese, for example, inclusive or exclusive 我們/我们 wǒmen is the plural form of singular 我 wǒ "I", and inclusive 咱們/咱们 zánmen is a separate root. However, in Hadza, the inclusive, ’one-be’e, is the plural of the singular ’ono (’one-) "I", and the exclusive, ’oo-be’e, is a separate [dubious – discuss] root.[citation needed]

It is not uncommon for two separate words for "I" to pluralize into derived words, which have a clusivity distinction. For example, in Vietnamese, the familiar word for "I" (ta) pluralizes to inclusive we (chúng ta), and the formal or cold word for "I" (tôi) pluralizes into exclusive we (chúng tôi). In Samoan, the singular form of the exclusive is the regular word for "I", and the singular form of the inclusive may also occur on its own and then also means "I" but with a connotation of appealing or asking for indulgence.

In the Kunama language of Eritrea, the first-person inclusive and exclusive distinction is marked on dual and plural forms of verbs, independent pronouns, and possessive pronouns.[4]

Distinction in verbs

[edit]Where verbs are inflected for person, as in the native languages of Australia and in many Native American languages, the inclusive-exclusive distinction can be made there as well. For example, in Passamaquoddy, "I/we have it" is expressed

- Singular n-tíhin (first person prefix n-)

- Exclusive n-tíhin-èn (first person n- + plural suffix -èn)

- Inclusive k-tíhin-èn (inclusive prefix k- + plural -èn)

In Tamil, on the other hand, the two different pronouns have the same agreement in the verb.

First-person clusivity

[edit]First-person clusivity is a common feature among Dravidian, Kartvelian, and Caucasian languages,[5] Australian and Austronesian languages, and is also found in languages of eastern, southern, and southwestern Asia, Americas, and in some creole languages. Some Sub-Saharan African languages also make the distinction, such as the Fula language. No European language outside the Caucasus makes this distinction grammatically, but some constructions[example needed] may be semantically inclusive or exclusive.

Singular inclusive forms

[edit]Several Polynesian languages, such as Samoan and Tongan, have clusivity with overt dual and plural suffixes in their pronouns. The lack of a suffix indicates the singular. The exclusive form is used in the singular as the normal word for "I", but the inclusive also occurs in the singular. The distinction is one of discourse: the singular inclusive has been described as the "modesty I" in Tongan. It is often rendered in English as one, but in Samoan, its use has been described as indicating emotional involvement on the part of the speaker.

Second-person clusivity

[edit]In theory, clusivity of the second person should be a possible distinction, but its existence is controversial. Clusivity in the second person is conceptually simple but nonetheless if it exists is extremely rare, unlike clusivity in the first. Hypothetical second-person clusivity would be the distinction between "you and you (and you and you ... all present)" and "you (one or more addressees) and someone else whom I am not addressing currently." These are often referred to in the literature as "2+2" and "2+3", respectively (the numbers referring to second and third person as appropriate).

Some notable linguists, such as Bernard Comrie,[6] have attested that the distinction is extant in spoken natural languages, while others, such as John Henderson,[7] maintain that a clusivity distinction in the second person is too complex to process. Many other linguists take the more neutral position that it could exist but is nonetheless not currently attested.[2] Horst J. Simon provides a deep analysis of second-person clusivity in his 2005 article.[2] He concludes that oft-repeated rumors regarding the existence of second-person clusivity—or indeed, any [+3] pronoun feature beyond simple exclusive we[8] – are ill-founded, and based on erroneous analysis of the data.

Distribution of the clusivity distinction

[edit]The inclusive–exclusive distinction occurs nearly universally among the Austronesian languages and the languages of northern Australia, but rarely in the nearby Papuan languages. (Tok Pisin, an English-Melanesian creole, generally has the inclusive–exclusive distinction, but this varies with the speaker's language background.) It is widespread in India, featuring in the Dravidian, Kiranti, and Munda languages, as well as in several Indo-European languages of India such as Odia, Marathi, Rajasthani, Punjabi, Dakhini, and Gujarati (which either borrowed it from Dravidian or retained it as a substratum while Dravidian was displaced). It can also be found in the languages of eastern Siberia, such as Tungusic, as well as northern Mandarin Chinese. In indigenous languages of the Americas, it is found in about half the languages, with no clear geographic or genealogical pattern. It is also found in a few languages of the Caucasus and Sub-Saharan Africa, such as Fulani, and Khoekhoe.[9][10]

It is, of course, possible in any language to express the idea of clusivity semantically, and many languages provide common forms that clarify the ambiguity of their first person pronoun (English "the rest of us", Italian noialtri). A language with a true clusivity distinction, however, does not provide a first-person plural with indefinite clusivity in which the clusivity of the pronoun is ambiguous; rather, speakers are forced to specify by the choice of pronoun or inflection, whether they are including the addressee or not. That rules out most European languages, for example. Clusivity is nonetheless a very common language feature overall. Some languages with more than one plural number make the clusivity distinction only in, for example, the dual but not in the greater plural, but other languages make it in all numbers. In the table below, the plural forms are the ones preferentially listed.

| Language | Inclusive form | Exclusive form | Singular related to | Notes | Language family |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ainu | a-/an- | ci- | ?? | Ainu | |

| American Sign Language (ASL) | "K" tips up palm in (dual) "1" tap chest + twist (pl) |

"K" tips up palm side (dual) "1" tap each side of chest (pl) |

Exclusive plural | French Sign Language | |

| Anishinaabemowin | giinwi | niinwi | Both | The inclusive form is derived from the second-person singular, and the exclusive form is derived from first-person singular. | Algonquian |

| Apma | kidi | gema | Neither | Subject prefixes are ta- (inclusive) and kaa(ma)- (exclusive). There are also dual forms, which are derived from the plurals. | Austronesian |

| Aymara | jiwasa | naya | Exclusive | The derived form jiwasanaka of the inclusive refers to at least three people. | Aymaran |

| Bikol | kita | kami | Neither | Austronesian | |

| Bislama | yumi | mifala | Both | The inclusive form is derived from the second-person pronoun and the first-person pronoun. There are also dual and trial forms. | English creole |

| Cebuano | kita | kami | Neither | Short forms are ta (incl.) and mi (excl.) | Austronesian |

| Chechen | vai | txo | Neither | Caucasian | |

| Cherokee | ᎢᏂ (ini- (dual)), ᎢᏗ (idi- (plural)) | ᎣᏍᏗ (osdi- (dual)), ᎣᏥ (oji- (plural)) | Neither | The forms given here are the active verb agreement prefixes. Free pronouns do not distinguish clusivity. | Iroquoian |

| Cree, Plains | ᑭᔮᓇᐤ (kiyānaw) |

ᓂᔭᓈᐣ (niyanān) |

Both | The inclusive form is derived from the second-person singular pronoun, and the exclusive form is derived from the first-person singular. | Algonquian |

| Cree, Moose | ᑮᓛᓈᐤ (kîlânâw) |

ᓃᓛᐣ (nîlân) |

Both | The inclusive form is derived from the second-person singular pronoun, and the exclusive form is derived from the first-person singular. | Algonquian |

| Cree, Swampy | ᑮᓈᓇᐤ (kīnānaw) |

ᓃᓇᓈᐣ (nīnanān) |

Both | The inclusive form is derived from the second-person singular, whereas the exclusive form is derived from the first-person singular. | Algonquian |

| Cree, Woods | ᑮᖭᓇᐤ (kīthānaw) |

ᓂᖬᓈᐣ (nīthanān) |

Both | The inclusive form is derived from the second-person singular, and the exclusive form is derived from the first-person singular. | Algonquian |

| Dakhini | apan اپن | ham ہم | Indo-European | ||

| Daur | baa | biede | ?? | Mongolic | |

| Evenki | mit | bū | ?? | Tungusic | |

| Fijian | kedatou† | keitou ("we" but excludes the person spoken to) | "kedaru" also means "we" but is limited to the speaker and the person spoken to and can be translated as "you and me". † ("we" but includes both the person spoken to and the speaker as part of a finite group. To refer to a much larger group, like humanity or a race of people, "keda" is used instead. |

Austronesian | |

| Fula | 𞤫𞤲 (en), 𞤫𞤯𞤫𞤲 (eɗen) | 𞤥𞤭𞤲 (min), 𞤥𞤭𞤯𞤫𞤲 (miɗen) | Exclusive (?) | Examples show short- and long-form subject pronouns. | Niger-Congo |

| Guarani | ñande | ore | Neither | Tupi-Guarani | |

| Gujarati | આપણે /aˑpəɳ(eˑ)/ | અમે /əmeˑ/ | Exclusive | Indo-European | |

| Hadza | onebee | ôbee | Inclusive | Hadza (isolate) | |

| Hawaiian | kāua (dual); kākou (plural) | māua (dual); mākou (plural) | Neither | Austronesian | |

| Ilocano | datayó, sitayó | dakamí, sikamí | Neither | The dual inclusives datá and sitá are widely used. | Austronesian |

| Juǀʼhoan | mtsá (dual); m, mǃá (plural) | ètsá (dual); è, èǃá (plural) | Neither | The plural pronouns è and m are short forms. | Kxʼa |

| Kapampangan | ikatamu | ikami | Neither | The dual inclusive ikata is widely used. | Austronesian |

| Australian Kriol | yunmi | melabat | Exclusive | The inclusive form is derived from the second-person pronoun and the first-person pronoun. The exclusive form is derived from the first-person singular and the third-person plural. There are significant dialectal and diachronic variations in the exclusive form. | English creole |

| Lakota | uŋ(k)- | uŋ(k)- ... -pi | Neither | The inclusive form has a dual number. By adding the suffix -pi, it takes the plural number. In the plural form, no clusivity distinction is made. | Siouan |

| Lojban | mi'o | mi'a/mi | Both | There is also the form ma'a, which means the speaker, the listener, and others unspecified. However, the first-person pronoun mi take no number and can refer to any number of individuals in the same group; mi'a and mi'o are usually preferred. | Constructed language |

| Maguindanaon | sekitanu | sekami | Neither | Austronesian | |

| Malagasy | Isika | Izahay | – | Austronesian | |

| Manchu | muse | be | Exclusive | Tungusic | |

| Malay | kita | kami | Neither | The exclusive form is hardly used in informal Indonesian in the Jakarta area. Instead, kita is almost always used colloquially to indicate both inclusive and exclusive "we". However, in more formal circumstances (both written and spoken), the distinction is clear and well-practiced. Therefore, kami is absolutely exclusive, but kita may generally mean both inclusive and exclusive "we" depending on the circumstances. That phenomenon is less frequently encountered in Malaysia. | Austronesian |

| Malayalam | നമ്മൾ (nammaḷ) | ഞങ്ങൾ (ñaṅṅaḷ) | Exclusive | Dravidian | |

| Mandarin | 咱們 / 咱们 (zánmen) | 我們 / 我们 (wǒmen) | Exclusive | 我们 is used both inclusively and exclusively by most speakers, especially in formal situations. Use of 咱们 is common only in northern dialects, notably that of Beijing, and may be from Manchu influence.[11] | Sino-Tibetan |

| Māori | tāua (dual); tātou (plural) | māua (dual); mātou (plural) | Neither | Austronesian | |

| Marathi | आपण /aˑpəɳ/ | आम्ही /aˑmʱiˑ/ | Exclusive | Indo-European | |

| Marwari | /aˑpãˑ/ | /mɦẽˑ/ | Exclusive | Indo-European | |

| Southern Min | 咱 (lán) | 阮 (goán/gún) | Exclusive | Sino-Tibetan | |

| Newar language | Jhi: sa:n (झि:सं:) | Jim sa:n (जिम् सं:) | Both are used as possessive pronouns. | Sino-Tibetan | |

| Pohnpeian | kitail (plural), kita (dual) | kiht (independent), se (subject) | There is an independent (non-verbal) and subject (verbal) pronoun distinction. The exclusive includes both dual and plural, and the independent has a dual-plural distinction. | Austronesian | |

| Potawatomi | ginan, g- -men (short), gde- -men (long) | ninan, n- -men(short), nde- -men (long) | ?? | Potawatomi has two verb conjugation types, "short" and "long." Both are listed here, and labeled as such. | Central Algonquian |

| Punjabi | ਆਪਾਂ (apan) | ਅਸੀਂ (asin) | Indo-European | ||

| Quechuan languages | ñuqanchik | ñuqayku | Both | Quechuan | |

| Shawnee | kiilawe | niilawe | Exclusive | The inclusive form is morphologically derived from the second-person pronoun kiila. | Algic |

| Tagalog | táyo | kamí | Neither | Austronesian | |

| Tausug | kitaniyu | kami | ?? | The dual inclusive is kita. | Austronesian |

| Tamil | நாம் (nām) | நாங்கள் (nāṅkaḷ) | Exclusive | Dravidian | |

| Telugu | మనము (manamu) | మేము (memu) | Exclusive | Dravidian | |

| Tetum | ita | ami | Neither | Austronesian | |

| Tok Pisin | yumipela | mipela | Exclusive | The inclusive form is derived from the second-person pronoun and the first-person pronoun. There are also dual and trial forms. | English creole |

| Tupi | îandé | oré | Inclusive | Tupi-Guarani | |

| Tulu | nama | yenkul | Dravidian | ||

| Udmurt[12] | as'meos (асьмеос);[12] ваньмы ("we all together")[13] | mi (ми) | exclusive | The form as'meos seem to become obsolete and 'mi' is always used instead by younger generations, probably under the influence of Russian 'my' (мы) for 'we'.[12] | Permic |

| Vietnamese | chúng ta | chúng tôi | Exclusive | The exclusive form is derived from the formal form of I, tôi | Austroasiatic |

References

[edit]- ^ Filimonova, Elena (30 November 2005). Clusivity: Typology and case studies of the inclusive-exclusive distinction. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9789027293886 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Simon, Horst J. (2005). "Only you? Philological investigations into the alleged inclusive-exclusive distinction in the second person plural" (PDF). In Filimonova, Elena (ed.). Clusivity: Typology and case studies of the inclusive-exclusive distinction. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: King's College London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-09. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ^ Mary Haas. 1969. "Exclusive" and "inclusive": A look at early usage. International Journal of American Linguistics 35:1-6. JSTOR 1263878.

- ^ Thompson, E. D. 1983. "Kunama: phonology and noun phrase" in M. Lionel Bender (ed.): Nilo-Saharan Language Studies, pp. 280–322. East Lansing: African Studies Center, Michigan State University.

- ^ Awde, Nicholas; Galaev, Muhammad (22 May 2014). Chechen-English English-Chechen Dictionary and Phrasebook. Routledge. ISBN 9781136802331 – via Google Books.

- ^ Comrie, Bernard. 1980. "Review of Greenberg, Joseph H. (ed.), Universals of human language, Volume 3: Word Structure (1978)". Language 56: p837, as quoted in Simon 2005. Quote: One pair of combinations not discussed is the opposition between 2nd person non-singular inclusive (i.e. including some third person) and exclusive, which is attested in Southeast Ambrym.

- ^ Henderson, T.S.T. 1985. "Who are we, anyway? A study of personal pronoun systems". Linguistische Berichte 98: p308, as quoted in Simon 2005. Quote: My contention is that any language which provided more than one 2nd person plural pronoun, and required the speaker to make substantial enquiries about the whereabouts and number of those referred to in addition to the one person he was actually addressing, would be quite literally unspeakable.

- ^ One treated example is the Ghomala' language of Western Cameroon, which has been said to have a [1+2+3] first-person plural pronoun, but a more recent analysis by Wiesemann (2003) indicates that such pronouns may be limited to ceremonial use.

- ^ http://wals.info/chapter/39 World Atlas of Language Structures 39: Inclusive/Exclusive Distinction in Independent Pronouns

- ^ http://wals.info/chapter/40 World Atlas of Language Structures 40: Inclusive/Exclusive Distinction in Verbal Inflection

- ^ Matthews, 2010. "Language Contact and Chinese". In Hickey, ed., The Handbook of Language Contact, p 760.

- ^ a b c К проблеме категории инклюзивности местоимений в удмуртском языке

- ^ [1]

Further reading

[edit]- Jim Chen, First Person Plural (analyzing the significance of inclusive and exclusive we in constitutional interpretation)

- Payne, Thomas E. (1997), Describing morphosyntax: A guide for field linguists, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-58224-5

- Filimonova, Elena (eds). (2005). Clusivity: Typological and case studies of the inclusive-exclusive distinction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 90-272-2974-0.

- Kibort, Anna. "Person." Grammatical Features. 7 January 2008. [2] Retrieved on 16 March 2020.

Clusivity

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Core Concept

Clusivity refers to the grammatical distinction in first-person plural pronouns (and sometimes related forms) between inclusive variants, which include both the speaker and the addressee (along with possible others), and exclusive variants, which include the speaker and others but exclude the addressee.[1][2] This opposition allows speakers to encode whether the addressee is part of the referent group, a feature absent in languages like English, where a single "we" neutralizes the distinction.[1] The phenomenon appears in approximately one-third of the world's languages, particularly in families such as Austronesian, Dravidian, and some Papuan and Australian groups.[2] In a basic schematic paradigm, first-person non-singular forms (dual or plural) split into two categories: the inclusive form, often glossed as "we (inclusive)" to denote speaker + addressee (+ others), and the exclusive form, glossed as "we (exclusive)" for speaker + others (not addressee).[1] For instance, in many languages with clusivity, the inclusive may derive semantically from combining first- and second-person features, while the exclusive results from exhaustifying a broader participant set to exclude the addressee.[2] This binary split is primarily pronominal but can extend to verbal agreement in some systems.[6] The inclusive-exclusive distinction was first systematically described in European linguistics in 1560 by Domingo de Santo Tomás in his grammar of Quechua, where he noted the opposition in Andean languages.[1] It gained prominence in typological studies through reconstructions of Proto-Austronesian pronouns, notably in Robert Blust's 1977 analysis, which identified *kami (exclusive) and *kita (inclusive) as inherited forms, highlighting the feature's deep roots in Austronesian subgrouping and its near-universal presence in the family. The modern term "clusivity" emerged in the early 2000s to encompass broader inclusion-exclusion patterns beyond pronouns.[6] Semantically, clusivity serves as a form of social deixis, anchoring participant roles relative to the discourse context by positioning the addressee inside or outside the speaker's referential group, often via metaphorical mappings of inclusion (e.g., shared space) versus exclusion (e.g., boundary separation).[6] This encoding influences discourse dynamics, signaling solidarity or dissociation among interlocutors based on their relational status.[2]Inclusive vs. Exclusive Distinction

The inclusive-exclusive distinction in clusivity represents a fundamental binary in the semantics of first-person plural reference, where the inclusive form denotes a group comprising both the speaker (author) and the addressee (participant), often signaling cooperation or shared perspective, as seen in Evenki mit ("we inclusive") used in contexts of joint action.[2] In contrast, the exclusive form refers to a group that includes the speaker but explicitly excludes the addressee, typically conveying separation or opposition, exemplified by Evenki bu ("we exclusive") in scenarios where the addressee is not part of the referenced collective.[2] This opposition arises semantically through mechanisms like exhaustification, where the exclusive emerges as a strengthened interpretation of a basic first-person form in competition with the inclusive, rather than as a primitive category.[2] Pragmatically, the choice between inclusive and exclusive forms influences interpersonal dynamics, such as politeness and solidarity, by aligning or distancing the speaker from the addressee within the discourse context. Inclusive forms promote solidarity and positive politeness by invoking shared identity and common ground, as in political speeches where "we" fosters unity between speaker and audience to build cohesion.[7] Exclusive forms, conversely, can heighten conflict or dissociation, signaling opposition and negative face-threatening acts, such as excluding adversaries in rhetorical strategies to emphasize division.[6] In languages without clusivity, like English, the single "we" resolves such ambiguities pragmatically through context—e.g., "We won the game" might exclude the addressee if spoken competitively, relying on inference for inclusion or exclusion.[7] A rare extension beyond this binary appears in some languages' hortative or minimal inclusive forms, which specify a restricted dual inclusive ("you and I only") distinct from broader plurals, as in minimal-augmented systems where the dual is limited to the inclusive to mark intimate joint reference.[1] For instance, certain Austronesian languages encode this minimal inclusive in dual pronouns, providing a third category for precise speaker-addressee pairing without encompassing larger groups.[1] Theoretically, clusivity integrates with deictic theory by treating the speaker and addressee as core deictic roles, where inclusive forms expand the deictic center to include both, while exclusives contract it to the speaker's group, often analyzed through deictic shift operations in discourse.[7] This framework highlights pragmatic markedness, with inclusive often carrying a marked status due to its explicit inclusion of the addressee, influencing discourse markedness in contexts of asymmetry or emphasis.[7]Grammatical Realizations

Pronominal Morphology

Clusivity is most commonly encoded in pronominal morphology through suppletion, where inclusive and exclusive forms derive from entirely distinct roots, as seen in patterns like AAA (identical singular and non-singular forms extending to inclusive), ABB (singular matching exclusive, differing for inclusive), ABC (all three distinct), and AAB (singular and inclusive sharing roots, differing for exclusive).[8] These suppletive patterns reflect a containment hierarchy where the inclusive form incorporates features of both speaker and hearer, precluding unattested ABA configurations (singular matching inclusive, exclusive differing).[8] Affixation provides another strategy, often marking the more complex inclusive form with suffixes or prefixes, such as the inclusive suffix *-e'ex in Itzaj Maya (1pl inclusive *to'on-e'ex) or the exclusive suffix *-ge in Limbu (1pl exclusive *angi-ge). Portmanteau morphemes, which fuse person, number, and clusivity into single forms, also occur, as in Dolakha Newar where the 1pl inclusive *chiji encodes multiple features compactly.[8] The distinction is sensitive to number, appearing predominantly in non-singular forms like dual and plural, while singular inclusive pronouns represent an extremely rare pattern with no well-attested examples in Formosan languages.[9] In most languages, clusivity emerges only beyond the singular, aligning with the inherent plurality of inclusive reference that incorporates the addressee.[8] Cross-person patterns center on the first person, with the inclusive/exclusive split prototypically in the first-person plural (1pl), but extending to first-person dual (1du) in languages with elaborate number systems and occasionally to second-person forms in rare cases like honorific or reciprocal extensions. For instance, in Tagalog (an Austronesian language of the Philippines), the 1pl inclusive tayo (speaker + hearer + others) contrasts suppletively with the 1pl exclusive kami (speaker + others), both extending from the 1sg ako, while no singular clusivity applies.| Person/Number | Form | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| 1sg | ako | I |

| 1pl inclusive | tayo | we (incl. hearer) |

| 1pl exclusive | kami | we (excl. hearer) |

| Number | Inclusive Form | Exclusive Form |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | (N/A) | au |

| Dual | kedaru | keirau |

| Trial | kedatou | keitou |

| Plural | keda | keimami |