Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Algebraic connectivity

View on Wikipedia

The algebraic connectivity (also known as Fiedler value or Fiedler eigenvalue after Miroslav Fiedler) of a graph G is the second-smallest eigenvalue (counting multiple eigenvalues separately) of the Laplacian matrix of G.[1] This eigenvalue is greater than 0 if and only if G is a connected graph. This is a corollary to the fact that the number of times 0 appears as an eigenvalue in the Laplacian is the number of connected components in the graph. The magnitude of this value reflects how well connected the overall graph is. It has been used in analyzing the robustness and synchronizability of networks.

Properties

[edit]

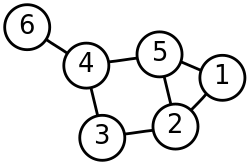

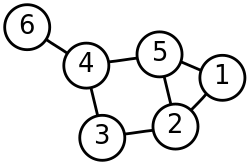

The algebraic connectivity of undirected graphs with nonnegative weights is , with the inequality being strict if and only if G is connected. However, the algebraic connectivity can be negative for general directed graphs, even if G is a connected graph.[2] Furthermore, the value of the algebraic connectivity is bounded above by the traditional (vertex) connectivity of a graph, , unless the graph is complete (the algebraic connectivity of a complete graph Kn is its order n).[3] For an undirected connected graph with nonnegative edge weights, n vertices, and diameter D, the algebraic connectivity is also known to be bounded below by ,[4] and in fact (in a result due to Brendan McKay) by .[5] For the example graph with 6 nodes show above (), these bounds would be calculated as:Unlike the traditional form of graph connectivity, defined by local configurations whose removal would disconnect the graph, the algebraic connectivity is dependent on the global number of vertices, as well as the way in which vertices are connected. In random graphs, the algebraic connectivity decreases with the number of vertices, and increases with the average degree.[6]

The exact definition of the algebraic connectivity depends on the type of Laplacian used. Fan Chung has developed an extensive theory using a rescaled version of the Laplacian, eliminating the dependence on the number of vertices, so that the bounds are somewhat different.[7]

In models of synchronization on networks, such as the Kuramoto model, the Laplacian matrix arises naturally, so the algebraic connectivity gives an indication of how easily the network will synchronize.[8] Other measures, such as the average distance (characteristic path length) can also be used,[9] and in fact the algebraic connectivity is closely related to the (reciprocal of the) average distance.[5]

The algebraic connectivity also relates to other connectivity attributes, such as the isoperimetric number, which is bounded below by half the algebraic connectivity.[10]

Fiedler vector

[edit]The original theory related to algebraic connectivity was produced by Miroslav Fiedler.[11][12] In his honor the eigenvector associated with the algebraic connectivity has been named the Fiedler vector. The Fiedler vector can be used to partition a graph.

Partitioning a graph using the Fiedler vector

[edit]

For the example graph in the introductory section, the Fiedler vector is . The negative values are associated with the poorly connected vertex 6, and the neighbouring articulation point, vertex 4; while the positive values are associated with the other vertices. The signs of the values in the Fiedler vector can therefore be used to partition this graph into two components: . Alternatively, the value of 0.069 (which is close to zero) can be placed in a class of its own, partitioning the graph into three components: or moved to the other partition , as pictured. The squared values of the components of the Fiedler vector, summing up to one since the vector is normalized, can be interpreted as probabilities of the corresponding data points to be assigned to the sign-based partition.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Algebraic Connectivity." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource.

- ^ Wu, Chai Wai (2005). "Algebraic connectivity of directed graphs". Linear and Multilinear Algebra. 53 (3). Taylor and Francis: 203–223. doi:10.1080/03081080500054810. S2CID 121368189.

Even if G is quasi-strongly connected, which is equivalent to G containing a directed spanning tree, a(G) can still be nonpositive as the exploding star and Theorem 1 indicate.

- ^ Fiedler, Miroslav (1973). "Algebraic connectivity of graphs". Czechoslovak Mathematical Journal. 23 (2): 298–305. doi:10.21136/cmj.1973.101168. ISSN 0011-4642.

- ^ Gross, J.L.; Yellen, J., eds. (2004). Handbook of Graph Theory. CRC Press. p. 571. doi:10.1201/b16132. hdl:2117/22000. ISBN 0-203-49020-7.

- ^ a b Mohar, Bojan (1991). "The Laplacian Spectrum of Graphs" (PDF). In Alavi, Y.; Chartrand, G.; Oellermann, O.R.; Schwenk, A.J. (eds.). Graph Theory, Combinatorics, and Applications. Proceedings of the sixth quadrennial international conference on the theory and applications of graphs. Vol. 2. Wiley. pp. 871–898. Zbl 0840.05059.

- ^ Holroyd, Michael (2006). "Synchronization and Connectivity of Discrete Complex Systems". International Conference on Complex Systems.

- ^ Chung, F.R.K. (1997). Spectral Graph Theory. Regional Conference Series in Mathematics. Vol. 92. Amer. Math. Soc. ISBN 0-8218-8936-2. Incomplete revised edition

- ^ Pereira, Tiago (2011). "Stability of Synchronized Motion in Complex Networks". arXiv:1112.2297 [nlin.AO].

- ^ Watts, D. (2003). Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age. Vintage. ISBN 0-434-00908-3. OCLC 51622138.

- ^ Biggs, Norman (1993). Algebraic Graph Theory (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 28, 58. ISBN 0-521-45897-8.

- ^ Fiedler, M. (1973). "Algebraic connectivity of Graphs". Czechoslovak Mathematical Journal. 23 (98): 298–305. doi:10.21136/CMJ.1973.101168. MR 0318007. Zbl 0265.05119.

- ^ Fiedler, M. (1989) [1987]. "Laplacian of graphs and algebraic connectivity". Banach Center Publications. 25 (1): 57–70. doi:10.4064/-25-1-57-70.