Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Altered chord

View on Wikipedia

An altered chord is a chord that replaces one or more notes from the diatonic scale with a neighboring pitch from the chromatic scale. By the broadest definition, any chord with a non-diatonic chord tone is an altered chord. The simplest example of altered chords is the use of borrowed chords, chords borrowed from the parallel key, and the most common is the use of secondary dominants. As Alfred Blatter explains, "An altered chord occurs when one of the standard, functional chords is given another quality by the modification of one or more components of the chord."[2]

For example, altered notes may be used as leading tones to emphasize their diatonic neighbors. Contrast this with chord extensions:

Whereas chord extension generally involves adding notes that are logically implied, chord alteration involves changing some of the typical notes. This is usually done on dominant chords, and the four alterations that are commonly used are the ♭5, ♯5, ♭9 and ♯9. Using one (or more) of these notes in a resolving dominant chord greatly increases the bite in the chord and therefore the power of the resolution.[3]

In jazz harmony, chromatic alteration is either the addition of notes not in the scale or expansion of a [chord] progression by adding extra non-diatonic chords.[4] For example, "A C major scale with an added D♯ note, for instance, is a chromatically altered scale" while, "one bar of Cmaj7 moving to Fmaj7 in the next bar can be chromatically altered by adding the ii and V of Fmaj7 on the second two beats of bar" one. Techniques include the ii–V–I turnaround, as well as movement by half-step or minor third.[5]

The five most common types of altered dominants are: V+, V7♯5 (both with raised fifths), V♭5, V7♭5 (both with lowered fifths), and Vø7 (with lowered fifth and third, the latter enharmonic to a raised ninth).[6]

Background

[edit]

"Borrowing" of this type appears in music from the Renaissance music era and the Baroque music era (1600–1750)—such as with the use of the Picardy third, in which a piece in a minor key has a final or intermediate cadence in the tonic major chord. "Borrowing" is also common in 20th century popular music and rock music.

For example, in music in a major key, such as C major, composers and songwriters may use a B♭ major chord, that they "borrow" from the key of C minor (where it is the VII chord). Similarly, in music in a minor key, composers and songwriters often "borrow" chords from the tonic major. For example, pieces in C minor often use F major and G major (IV and V chords), which they "borrow" from C major.

More advanced types of altered chords were used by Romantic music era composers in the 19th century, such as Chopin, and by jazz composers and improvisers in the 20th and 21st century. For example, the chord progression on the left uses four unaltered chords, while the progression on the right uses an altered IV chord and is an alteration of the previous progression:[1]

The A♭ in the altered chord serves as a leading tone to G, which is the root of the next chord.

The object of such foreign tones is: to enlarge and enrich the scale; to confirm the melodic tendency of certain tones...; to contradict the tendency of others...; to convert inactive tones into active [leading tones]...; and to affiliate the keys, by increasing the number of common tones.[7]

According to one definition, "when a chord is chromatically altered, and the thirds remain large [major] or small [minor], and is not used in modulation, it is an altered chord."[9] According to another, "all chords...having a major third, i.e., either triads, sevenths, or ninths, with the fifth chromatically raised or chromatically lowered, are altered chords," while triads with a single altered note are considered, "changes of form [quality]," rather than alteration.[10]

According to composer Percy Goetschius, "Altered...chords contain one or more tones written with accidentals (♯, ♭, or ♮) and therefore foreign to the scale in which they appear, but nevertheless, from their connections and their effect, obviously belonging to the principal key of their phrase."[7] Richard Franko Goldman argues that, once one accepts, "the variability of the scale," the concept of altered chords becomes unnecessary: "In reality, there is nothing 'altered' about them; they are entirely natural elements of a single key system,"[11] and it is, "not necessary," to use the term as each 'altered chord' is, "simply one of the possibilities regularly existing and employed."[12]

Dan Haerle argues that only fifths and ninths may be altered, as all other alterations may be interpreted as an unaltered chord tone or, enharmonically, as an altered fifth or ninth (for example, ♯1 = ♭9 and ♭4 = 3).[13][14]

Altered seventh chord

[edit]

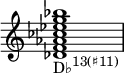

An altered seventh chord is a seventh chord with one, or all,[15] of its factors raised or lowered by a semitone (altered), for example, the augmented seventh chord (7+ or 7+5) featuring a raised fifth (C E G♯ B♭ [16] (C7+5: C–E–G♯–B♭). The factors most likely to be altered are the fifth, then the ninth, then the thirteenth.[15] In classical music, the raised fifth is more common than the lowered fifth, which in a dominant chord adds Phrygian flavor through the introduction of ♭![]() .[8]

.[8]

Altered dominant chord

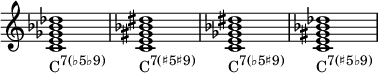

[edit]An altered dominant chord is, "a dominant triad of a 7th chord that contains a raised or lowered fifth and sometimes a lowered 3rd."[17] According to Dan Haerle, "Generally, altered dominants can be divided into three main groups: altered 5th, altered 9th, and altered 5th and 9th."[13] This definition allows three to five options, including the original:

|

|

Alfred Music gives nine options for altered dominants,[14] the last four of which contain two alterations each:[18][19]

|

|

Pianist Noah Baerman writes that "The point of having an altered note in a dominant chord is to build more tension (leading to a correspondingly more powerful resolution)."[18]

Alt chord

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2018) |

In jazz, the term altered chord, notated generally as a root, followed by 7alt (e.g. G7alt), refers to a dominant chord that fits entirely into the altered scale of the root. This means that the chord has the root, major third, minor seventh, and one or more altered tones, but does not have the natural fifth, ninth, eleventh, or thirteenth. An altered chord typically contains both an altered fifth and an altered ninth. To alter a tone is simply to raise or lower it by a semitone.

Altered chords may include both a flattened and sharpened form of the altered fifth or ninth, e.g. A7(♭5♭9♯9); however, it is more common to use only one such alteration per tone, e.g. B7(♯5♭9) (which may also be spelled as B7(♭9♭13)).

The raised fifteenth is only used when the ninth in a chord is natural. It functions as a minor ninth, creating a major seventh interval with the natural ninth, assuming that the chord is in root position. The notation of a raised fifteenth is a fairly modern addition to Western harmony, and they have been popularized by contemporary musicians like Jacob Collier. Natural fifteenths are never notated as alterations or extensions, as they are enharmonically equivalent to the root. For example, a chord that includes a raised fifteenth could look something like Gmaj13(♯11♯15), or if it were written as a polychord, Amaj7/Gmaj7.

In practice, many fake books do not specify all the alterations; the chord is typically just labelled as G7alt, and the alteration of ninths, elevenths, thirteenths, and fifteenths is left to the artistic discretion of the comping musician. The use of chords labeled G7alt can create challenges in jazz ensembles where more than one chordal instrument are playing chords (e.g., a large band with an electric guitar, piano, vibes, and/or a Hammond organ), because the guitarist might interpret a G7alt chord as containing a ♭9 and ♯11, whereas the organ player may interpret the same chord as containing a ♯9 and a ♭13, resulting in every tone from the altered scale at once, likely a far denser and more dissonant harmonic cluster than the composer intended. To deal with this issue, bands with more than one chordal instrument may work out the alt chord voicings beforehand or alternate playing of choruses.

The choice of inversion, or the omission of certain tones within the chord (e.g. omitting the root, common in jazz harmony and chord voicings), can lead to many different possible colorings, substitutions, and enharmonic equivalents. Altered chords are ambiguous harmonically, and may play a variety of roles, depending on such factors as voicing, modulation, and voice leading.

The altered chord's harmony is built on the altered scale (C, D♭, E♭, F♭, G♭, A♭, B♭, C), which includes all the alterations shown in the chord elements above:[20]

- root

- ♭9 (= ♭2)

- ♯9 (= ♯2 or ♭3)

- major third (enharmonically, as ♭4)

- ♯11 (= ♯4 or ♭5)

- ♭13 (= ♯5)

- ♭7

Because they do not have natural fifths, altered dominant (7alt) chords support tritone substitution (♭5 substitution). Thus, the 7alt chord on a given root can be substituted with the 13♯11 chord on the root a tritone away (e.g., G7alt is the same as D♭13♯11).

See also

[edit]- Altered scale – Seventh mode of the melodic minor scale

- Augmented sixth chord – Chord that contains the interval of an augmented sixth

- Bar-line shift – Jazz technique

- Blue note – Note sung or played at a slightly different pitch than standard

- Blues scale – Musical scales

- Harmonic major scale – Musical scale

- Jazz minor scale – Ascending form of the melodic minor scale

- Modal interchange – Chord borrowed from the parallel key

- Neapolitan chord – Major chord in music theory

- Phrygian dominant scale – Fifth mode of the harmonic minor scale

References

[edit]- ^ a b Erickson, Robert (1957). The Structure of Music: A Listener's Guide, p. 86. New York: Noonday Press. ISBN 0-8371-8519-X (1977 edition).

- ^ Blatter, Alfred (2007). Revisiting Music Theory: A Guide to the Practice, p. 186. ISBN 0-415-97440-2.

- ^ Baerman, Noah (1998). Complete Jazz Keyboard Method: Intermediate Jazz Keyboard, p. 70. ISBN 0-88284-911-5.

- ^ Arkin, Eddie (2004). Creative Chord Substitution for Jazz Guitar, p. 42. ISBN 0-7579-2301-1.

- ^ Arkin (2004), p. 43.

- ^ Benward and Saker (2009), p. 193.

- ^ a b Goetschius, Percy (1889). The Material Used in Musical Composition, pp. 123–124. G. Schirmer. [ISBN unspecified]

- ^ a b c Aldwell, Edward; Schachter, Carl; and Cadwallader, Allen (2010). Harmony & Voice Leading, p. 601. ISBN 9780495189756.

- ^ Bradley, Kenneth McPherson (1908). Harmony and Analysis, p. 119. C. F. Summy. [ISBN unspecified]

- ^ Norris, Homer Albert (1895). Practical Harmony on a French Basis, Volume 2, p. 48. H.B. Stevens. [ISBN unspecified]

- ^ Goldman, Richard Franko (1965). Harmony in Western Music, pp. 83–84. Barrie & Jenkins. ISBN 0-214-66680-8

- ^ Goldman (1965), p. 47.

- ^ a b Haerle, Dan (1983). Jazz Improvisation for Keyboard Players, Book two, p. 2.19. Alfred Music. ISBN 9780757930140

- ^ a b Alfred Music (2013). Mini Music Guides: Piano Chord Dictionary, pp. 22–23. Alfred Music. ISBN 9781470622244

- ^ a b Davis, Kenneth (2006). The Piano Professor Easy Piano Study, p. 78. ISBN 9781430303343.

- ^ Christiansen, Mike (2004). Mel Bay's Complete Jazz Guitar Method, Volume 1, p. 45. ISBN 9780786632633.

- ^ Benward, Bruce; Saker, Marilyn (2009). "Glossary", Music in Theory and Practice, Vol. II, p. 355. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0

- ^ a b Baerman, Noah (2000). Jazz Keyboard Harmony, p. 40. Alfred Music. ISBN 9780739011072

- ^ Baerman (1998), p. 74.

- ^ Brown, Buck; and Dziuba, Mark (2012). The Ultimate Guitar Chord & Scale Bible, p. 197. Alfred Music. ISBN 9781470622626 "In a dominant 7 context, this scale contains the root, 3rd, and ♭7 of the dominant chord and includes all of the available tensions: ♭9, ♯9, ♯11, and ♭13.

- ^ Coker, Jerry (1997). Elements of the Jazz Language for the Developing Improvisor, p. 81. ISBN 1-57623-875-X.

Further reading

[edit]- R., Ken (2012). DOG EAR Tritone Substitution for Jazz Guitar, Amazon, ASIN B008FRWNIW

Altered chord

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Definition

An altered chord, specifically an altered dominant seventh chord, is defined as a chord in which the fifth and/or ninth degrees are chromatically raised or lowered relative to the standard dominant seventh structure.[2] It is derived from the altered scale, also known as the super Locrian mode or diminished-whole tone scale, which provides the pitches for these modifications.[5] This scale consists of the root, minor second (or flat ninth), augmented second (or sharp ninth), major third, diminished fifth (or sharp eleventh), minor sixth (or flat thirteenth), and minor seventh.[3] The core components include the unaltered root, major third, and minor seventh, with the characteristic alterations appearing in the upper extensions, typically the flat ninth (♭9), sharp ninth (♯9), flat fifth (♭5), or sharp fifth (♯5).[3] These alterations introduce dissonant tensions that distinguish the chord from its more consonant counterparts. The primary function of an altered chord is to heighten dissonance and create a powerful sense of pull toward resolution, particularly to the tonic chord in a dominant-to-tonic progression.[5] This tension arises from the chromatic clashes, making it a staple in harmonic contexts requiring increased expressivity. In contrast to unaltered dominant seventh chords, which use natural ninth (9), eleventh (11), and thirteenth (13) extensions drawn from the Mixolydian mode for a more stable sound, altered chords prioritize these chromatic variants to amplify instability and forward momentum.[3] In jazz, they serve as a key tool for improvisation over dominant functions.[3]Chord Components

The altered chord derives its foundational structure from the dominant seventh chord, which comprises four essential intervals stacked in thirds: the root (1), major third (3), perfect fifth (5), and minor seventh (b7).[6] These core components form a major-minor seventh chord that inherently generates tension through the dissonance between the minor seventh and the root or third, propelling resolution to the tonic.[7] For instance, in the key of C major, the dominant seventh chord on G is notated as G7, consisting of G (root), B (major third), D (perfect fifth), and F (minor seventh).[8] The perfect fifth contributes relative stability to the chord's overall sonority, while the major third defines its major quality, and the minor seventh amplifies the pull toward resolution.[6] Beyond these primary tones, altered chords often incorporate upper extensions such as the major ninth (9), perfect eleventh (11), and major thirteenth (13), which are additional thirds stacked above the octave.[9] These extensions, referred to as tensions, add layers of color and complexity by introducing further dissonant intervals that interact with the core notes, enriching the harmonic texture while maintaining the chord's dominant function prior to modification.[10] Alterations to the altered chord typically involve chromatic adjustments to select components like the fifth or ninth.[2]Historical Context

Origins in Classical Music

The concept of altered chords began to emerge in the late Romantic era as composers explored chromatic harmony to heighten emotional tension and expand beyond diatonic frameworks. These proto-altered chords often involved selective chromatic modifications to standard harmonies, creating dissonance and ambiguity that foreshadowed later developments in harmonic practice.[11] Richard Wagner played a pivotal role in this evolution through his use of chromatic dominants, most notably in the opera Tristan und Isolde (composed 1857–1859). The famous "Tristan chord"—an augmented sixth chord functioning as an altered pre-dominant—appears in the prelude's opening measures, introducing chromatic alterations that blur tonal resolution and intensify the drama of unrequited love. This chord, built on F–B–D♯–G♯, resolves deceptively to a dominant seventh, exemplifying how Wagner employed such structures to dissolve traditional diatonic norms.[12] Franz Liszt similarly advanced the harmonic vocabulary by incorporating chromatic alterations, secondary dominants, and augmented chords in works like the Mephisto waltzes (1860–1885). These elements allowed Liszt to create omnitonic effects, undermining clear tonal centers and enabling freer, programmatic expression that pushed the boundaries of 19th-century harmony.[13] Secondary dominants and augmented sixth chords served as key influences, introducing alterations for heightened tension within classical progressions. Secondary dominants, as altered chords targeting non-tonic degrees, added chromatic leading tones to propel harmonic motion, while augmented sixth chords—chromatic variants of subdominant harmonies—expanded outward to dominants, enhancing pre-cadential drama. Both techniques, prevalent in Romantic repertoire, laid foundational precedents for more extensive alterations.[14][11]Development in Jazz and Modern Harmony

Altered chords, building upon foundational influences from classical music, underwent significant evolution in 20th-century jazz as musicians sought to expand harmonic possibilities for expressive improvisation.[15] In the 1940s, bebop marked a pivotal standardization of altered chords, with pioneers Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie integrating them to navigate rapid chord progressions and create tension leading to resolution. Parker, in particular, revolutionized solos by incorporating dissonant alterations into standard structures, as evident in his 1945 recording "Ko Ko," where altered tensions enhanced melodic complexity and technical virtuosity.[15] Gillespie complemented this by codifying altered harmonies in his compositions, fostering a style that prioritized harmonic innovation in small ensemble settings.[15] These techniques allowed improvisers to derive fresh lines from dominant chords, elevating bebop's intellectual and rhythmic demands.[16] By the late 1950s, altered chords adapted to modal jazz, as showcased in Miles Davis's landmark album Kind of Blue (1959), where they provided targeted color and tension amid extended static harmonies rather than dense progressions. In pieces like "So What," such tensions enriched the modal framework, enabling freer melodic exploration while maintaining subtle harmonic pull.[17] This modal integration influenced jazz fusion in the 1960s and 1970s, where altered chords infused rock and electric elements with sophisticated dissonance, as heard in works by artists like Miles Davis and Weather Report, blending bebop-derived tensions with broader textural palettes. These influences continue in contemporary jazz contexts. In contemporary contexts, altered chords persist in smooth jazz and film scores, contributing to atmospheric depth and emotional nuance through selective tensions that evoke suspense or resolution without overwhelming the melody. Theoretical formalization advanced in the 1960s and 1970s through educators like Barry Harris, whose harmonic method emphasized diminished scales over dominant chords to systematically generate altered substitutions, aiding improvisation and reharmonization in jazz pedagogy.[18] Harris's approach, rooted in bebop principles, promoted chromatic passing tones and scale families to access altered sounds, influencing generations of jazz musicians and theorists.[19]Construction and Alterations

Underlying Scale

The altered scale serves as the primary melodic foundation for constructing altered chords, particularly over dominant seventh chords, by supplying a complete set of chord tones and available tensions derived from a single scale pattern.[5] This scale is specifically the seventh mode of the melodic minor scale, featuring the interval formula .[20] To derive the altered scale, one constructs the melodic minor scale (with the pattern ) starting a half step above the root of the target chord and then begins the scale from that root note.[5] For instance, the C altered scale uses the D♭ melodic minor scale (D♭, E♭, E, G♭, A♭, B♭, C) but starts on C, yielding the notes C, D♭, E♭, E, G♭, A♭, B♭.[20] This structure ensures the scale includes the root, major third, and minor seventh of the chord while incorporating all potential dissonant alterations. Unlike the Mixolydian mode (), which provides only consonant extensions over a dominant chord, the altered scale introduces maximum tension through its flattened and sharpened notes.[20] It also differs from the whole-tone scale (), a symmetrical pattern lacking the minor seventh and emphasizing augmented intervals rather than the full spectrum of alterations like , , , and .[5] Thus, the altered scale uniquely encompasses every possible altered tension, making it the comprehensive source for building such chords.[20]Specific Alterations

The specific alterations applied to the dominant seventh chord modify the fifth, ninth, or thirteenth degrees chromatically to heighten dissonance and tension, while preserving the root, major third, and minor seventh as the chord's core defining elements.[2] These changes draw from the altered scale but emphasize selective chord tones for harmonic color.[21] Among the most common alterations are the flat ninth (b9, enharmonically equivalent to a lowered second or ♭2), sharp ninth (#9, enharmonically a flat third or b3), flat fifth (b5), and sharp fifth (#5, also notated as flat thirteenth or b13).[22][21] The natural eleventh is typically avoided in these voicings because its perfect fourth interval clashes severely with the major third, creating excessive dissonance unsuitable for the chord's function.[22] For instance, a C7 altered chord (C7alt) might incorporate C (root), E (major third), G♭ (b5), B♭ (minor seventh), D♭ (b9), E♭ (#9), and G♯ (#5), though not all alterations need to be voiced simultaneously—practitioners select based on context to balance tension.[22] Selection of these alterations is guided by principles of voice leading to ensure smooth resolution to the tonic chord, enhancing the dominant's pull. The b9 often moves down by half step to the root or octave of the tonic, providing a strong leading-tone effect, while the #5 descends by half step to the tonic's perfect fifth for consonant closure.[21] Similarly, the #9 may resolve upward to the major third of the tonic, and the b5 to the minor third in minor tonics, prioritizing stepwise motion to minimize leaps and maximize harmonic satisfaction.[2] These resolutions underscore the altered dominant's role in creating directed tension within jazz harmony.[22]Types and Variants

Altered Dominant Chord

The altered dominant chord refers to a dominant seventh chord functioning as V7 in a harmonic progression, where the fifth and ninth (and potentially other extensions) are chromatically altered to maximize tension before resolving to the tonic chord (I). This configuration retains the essential root, major third, and minor seventh while incorporating dissonant alterations such as the flat ninth (b9), sharp ninth (#9), flat fifth (b5), sharp fifth (#5), and flat thirteenth (b13), drawn from the altered scale (the seventh mode of melodic minor). These modifications create a highly unstable sound designed specifically for strong resolution in V-I cadences, commonly encountered in jazz and modern harmonic contexts.[2] Functionally, the altered dominant intensifies the inherent dissonance of the dominant seventh chord by amplifying the tritone interval between the major third and minor seventh, which serves as the primary driver of resolution to the tonic. The chromatic alterations introduce additional leading-tone relationships and clashing intervals—such as the b9 against the root or the #5 against the third—that heighten overall instability without altering the chord's core dominant function. For instance, in a C major context, a G7 altered might include notes like G-B-Db-F-Eb (root-third-b5-b7-b13), where the Db (b5) and Eb (b13) create sharpened tensions that resolve downward by half-step or whole-step to the C major tonic, enhancing the pull through increased chromatic density. This heightened tension distinguishes the altered dominant from unaltered dominants, making it ideal for emphatic cadential resolutions in ii-V-I progressions.[23] Compared to other dominant chord types, the altered dominant employs more extensive chromaticism than the Lydian dominant (which features a raised eleventh but omits the b9 and #9 for a brighter, less tense quality) or the half-whole diminished scale-based dominant (which includes b9, #9, and #11 but substitutes a natural thirteenth for the b13, resulting in slightly less downward resolution pull). The altered dominant's full suite of tensions thus provides the most aggressive, dissonant profile, prioritizing maximum instability over the relative consonance of these alternatives.[21]Altered Seventh Chord

The altered seventh chord extends beyond dominant functions to include modifications on minor and major seventh chords, introducing chromatic tensions that enhance expressivity in non-tonic roles. For instance, alterations on minor-major seventh chords or standard minor seventh chords can draw from the melodic minor scale to impart a sense of ambiguity or color without implying resolution to a dominant. Similarly, lowering the fifth in a minor seventh chord, such as C–E♭–G–B♭ to form C–E♭–F♯–B♭ (a half-diminished variant), allows for heightened dissonance in supportive harmonic positions.[24] In jazz harmony, these non-dominant altered seventh chords appear less frequently than their dominant counterparts but find application in ii-V-I progressions through modal interchange, where chords are borrowed from parallel modes to substitute or embellish the supertonic minor seventh. For example, in a C major ii-V-I (Dm7–G7–Cmaj7), the Dm7 might interchange with a borrowed D half-diminished from the parallel minor key, introducing tensions to add modal flavor and smooth voice leading without disrupting the progression's flow.[25] This technique, rooted in borrowing from Dorian, Aeolian, or Phrygian modes, enriches the ii chord's role as a pre-dominant, providing subtle color variations that contrast with the more tension-driven dominant alterations.[26] While dominant altered seventh chords remain the most prevalent in tonal practices, these broader variants underscore the chord's versatility in jazz frameworks.[22]Notation and Voicings

Standard Notation

In jazz lead sheets and scores, the primary symbolic representation for an altered chord is "C7alt" or the shorthand "Calt," which denotes a dominant seventh chord incorporating any alterations from the full palette of tensions, including the ♭5, ♯5, ♭9, and ♯9.[27] This notation allows musicians to interpret the chord using the altered dominant scale, providing flexibility in selecting specific altered notes without exhaustive specification.[28] For greater precision, especially in arrangements requiring particular tensions, the notation expands to explicitly list the alterations, such as "C7(b9,#9,b5,#5)," indicating the inclusion of a flat ninth, sharp ninth, flat fifth, and sharp fifth alongside the dominant seventh structure.[29] Historically, the symbol "C7+" has been employed to signify a dominant seventh chord with a sharpened fifth, reflecting an earlier convention for denoting this specific alteration.[30] International variations exist, with American shorthand like "C7alt" dominating jazz contexts due to its conciseness, while some European notations favor more descriptive formats, such as "C7(9b,11#)," to highlight specific altered extensions like the flat ninth and sharp eleventh.[31] These symbols guide performers in realizing the chord through appropriate voicings, ensuring the intended harmonic tension is conveyed.[32]Voicing Techniques

Voicing techniques for altered chords in jazz prioritize the strategic arrangement of chord tones and tensions to create tension and resolution while ensuring playability on instruments like piano and guitar. These methods often build upon standard notation as a foundation, adapting the written symbols into practical hand positions that emphasize the chord's dissonant qualities, such as the flat ninth (b9) and sharp fifth (#5), derived from the altered scale.[22] Common voicings for altered dominant chords include rootless configurations on piano, which omit the root—typically played by the bassist—and stack the third, flat seventh (b7), b9, and #5 to form compact upper structures that highlight the chord's altered character. For example, a G7 altered voicing might use B (third), F (b7), Ab (b9), and D♯ ( #5 ) in close position, allowing for smooth voice leading in progressions. On guitar, drop-2 voicings adapt four-note altered dominants by lowering the second-highest note an octave, creating open voicings that span the fretboard effectively; a common G7alt drop-2 might arrange F-B-Ab-D♯ with the B dropped, providing space for the tensions without overcrowding the strings.[33][21][34] Key considerations in these voicings involve prioritizing the guide tones—the third and b7—which define the chord's major-minor quality and dominant function, ensuring harmonic clarity amid the dissonances. Pianists and guitarists alike avoid clustered dissonances by spacing altered tensions (e.g., b9 and #5) outward from the guide tones, preventing muddiness and facilitating better resonance in ensemble settings. This approach maintains the altered chord's tension while promoting efficient voice leading to subsequent chords.[21][33] Instrument-specific applications distinguish between comping and soloing contexts. On piano, shell voicings—using just the third and b7 in the left hand, often with the root added sparingly—provide rhythmic support for comping behind soloists, while full extensions incorporating b9, #9, #5, and b13 in both hands enrich solo piano performances with layered textures. Guitarists employ drop-2 shells for comping to leave room for the bass, expanding to fuller altered voicings during solos to integrate melody and harmony seamlessly.[33][34]Applications in Composition

Role in Harmonic Progression

Altered chords, particularly altered dominant seventh chords denoted as V7alt, serve primarily as substitutes for standard dominant seventh chords (V7) in progressions resolving to the tonic (I), intensifying the inherent tension to create a more dramatic and colorful resolution. This substitution amplifies the pull toward the tonic by incorporating dissonant tensions that demand resolution, a technique widely used in jazz and modern harmonic practices to avoid the predictability of unaltered dominants.[35] In larger harmonic schemes, altered chords facilitate substitutions such as tritone replacements, where a dominant chord is exchanged for another whose root lies a tritone away—for example, Gb7alt substituting for C7—while maintaining the crucial guide tones (the major third and minor seventh) that ensure functional equivalence. This approach not only preserves the dominant-to-tonic resolution but also introduces chromatic bass motion for smoother voice leading. Additionally, altered chords appear in backcycling, chains of secondary dominants progressing by descending fifths, where they heighten the overall tension before ultimate resolution to the primary tonic.[36] Effective integration of altered chords in progressions relies on specific resolution rules to achieve smooth voice leading and harmonic coherence. For instance, the raised fifth (#5) of the V7alt typically resolves downward by half step to the perfect fifth of the I chord, while the flat ninth (b9) moves upward by half step to the root of the tonic, thereby channeling the added dissonance into consonant stability. These guidelines ensure that alterations enhance rather than disrupt the progression's flow.[35]Examples in Jazz Standards

One prominent example of an altered chord in jazz repertoire appears in Jerome Kern's 1939 standard "All the Things You Are," particularly in the bridge section (bars 17–24 in the standard 36-bar form in Ab major). Here, the progression modulates to E major, employing B7alt as the V7 chord resolving to Emaj7, which introduces chromatic tensions (such as b9 and #9) to heighten the dramatic shift from the preceding keys of Ab major and G major. This alteration enhances the song's cycle-of-fifths structure and is a staple in jazz performances, allowing improvisers to use the altered scale over B7alt for expressive dissonance before the resolution. A simplified excerpt of this section's chord chart is as follows:| Am7 | D7 | Gmaj7 | % |

| F#m7b5 | B7alt | Emaj7 | C7alt |

| Am7 | D7 | Gmaj7 | % |

| F#m7b5 | B7alt | Emaj7 | C7alt |

| Bmaj7 | % | | Gmaj7 | % | | Ebmaj7 | % |

| F#m7 | B7alt | | Em7 | A7alt | | Dm7 | G7alt |

| C#m7 | F#7alt | | Bmaj7 | % | (repeat cycle)

| Bmaj7 | % | | Gmaj7 | % | | Ebmaj7 | % |

| F#m7 | B7alt | | Em7 | A7alt | | Dm7 | G7alt |

| C#m7 | F#7alt | | Bmaj7 | % | (repeat cycle)

| Dmaj7 | % | | F#7alt | Bm7 |

| E7 | Am7 | | Dmaj7 | % |

| Dmaj7 | % | | F#7alt | Bm7 |

| E7 | Am7 | | Dmaj7 | % |