Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Picardy third

View on Wikipedia

A Picardy third, (/ˈpɪkərdi/; French: tierce picarde) also known as a Picardy cadence or Tierce de Picardie, is a major chord of the tonic at the end of a musical section that is either modal or in a minor key. This is achieved by raising the third of the expected minor triad by a semitone to create a major triad, as a form of resolution.[1]

For example, instead of a cadence ending on an A minor chord containing the notes A, C, and E, a Picardy third ending would consist of an A major chord containing the notes A, C♯, and E. The minor third between the A and C of the A minor chord has become a major third in the Picardy third chord.[2]

Philosopher Peter Kivy writes:

Even in instrumental music, the picardy third retains its expressive quality: it is the "happy third". ... Since at least the beginning of the seventeenth century, it is no longer enough to describe it as a resolution to the more consonant triad; it is a resolution to the happier triad as well. ... The picardy third is absolute music's happy ending. Furthermore, I hypothesize that in gaining this expressive property of happiness or contentment, the picardy third augmented its power as the perfect, most stable cadential chord, being both the most emotionally consonant chord, so to speak, as well as the most musically consonant.[3]

According to Deryck Cooke, "Western composers, expressing the 'rightness' of happiness by means of a major third, expressed the 'wrongness' of grief by means of the minor third, and for centuries, pieces in a minor key had to have a 'happy ending' – a final major chord (the 'tierce de Picardie') or a bare fifth."[4]

As a harmonic device, the Picardy third originated in Western music in the Renaissance era.

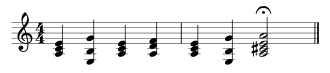

Illustration

[edit]

What makes this a Picardy cadence is shown by the red natural sign. Instead of the expected B-flat (which would make the chord minor) the accidental gives us a B natural, making the chord major.

Listen to the final four measures of "I Heard the Voice of Jesus Say" with (ⓘ) and without (ⓘ) Picardy third (harmony by R. Vaughan Williams).[5]

History

[edit]Name

[edit]The term was first used in 1768 by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, although the practice was used in music centuries earlier.[6][7] Rousseau argues that “the [practice] remained longer in Church Music, and, consequently, in Picardy, where there is music in a lot of cathedrals and churches,” and “the term is used jokingly by musicians”, suggesting it might have never had an academic basis, a tangible origin, and might have sprung out of idiomatic jokes in France in the first half of the 18th century.

Robert Hall hypothesizes that, instead of deriving from the Picardy region of France, it comes from the Old French word "picart", meaning "pointed" or "sharp" in northern dialects, and thus refers to the musical sharp that transforms the minor third of the chord into a major third.[8]

The few Old French dictionaries in which the word picart (fem. picarde) appears give “aigu, piquant” as a definition. While piquant is quite straightforward—meaning spiky, pointy, sharp—aigu is much more ambiguous, because it has the inconvenience of having at least three meanings: “high-pitched/treble”, “sharp” as in a sharp blade, and “acute”. Considering the definitions also state the term can refer to a nail ("clou") (read masonry nail), a pike or a spit, it seems aigu might be there used to mean "pointy" / “sharp”. However, not “sharp” in the desired sense, the one relating to a raised pitch, but in the sense of a sharp blade, which would thus completely discredit the word picart as the origin for the Picardy third, which also seems unlikely considering the possibility that aigu was also used to refer to a high(er)-pitched note, and a treble sound, thus perfectly explaining the use of the word picarde to designate a chord whose third is higher than it should be.[original research?]

Not to be ignored is the existence of the proverb "ressembler le Picard"[9] ("to resemble an inhabitant of Picard") which meant “éviter le danger” (to avoid danger). This would link back to the humorous character of the term, that would have thus been used to mock supposedly cowardly composers who used the Picardy third as a way to avoid the gravity of the minor third, and perhaps the backlash they would have faced from the academic elite and the Church by going against the time’s scholasticism.[original research?]

Ultimately, the origin of the name "tierce picarde" will likely never be known for sure, but what evidence there is seems to point towards these idiomatic jokes and proverbs as well as the literal meaning of picarde as high-pitched and treble.[original research?]

Use

[edit]In medieval music, such as that of Machaut, neither major nor minor thirds were considered stable intervals, and so cadences were typically on open fifths. As a harmonic device, the Picardy third originated in Western music in the Renaissance era. By the early seventeenth century, its use had become established in practice in music that was both sacred (as in the Schütz example above) and secular:

Examples of the Picardy third can be found throughout the works of J. S. Bach and his contemporaries, as well as earlier composers such as Thoinot Arbeau and John Blow. Many of Bach's minor key chorales end with a cadence featuring a final chord in the major:

In his book Music and Sentiment, Charles Rosen shows how Bach makes use of the fluctuations between minor and major to convey feeling in his music. Rosen singles out the Allemande from the keyboard Partita No. 1 in B-flat, BWV 825, to exemplify "the range of expression then possible, the subtle variety of inflections of sentiment contained with a well-defined framework". The following passage from the first half of the piece starts in F major, but then, in bar 15, "Turning to the minor mode with a chromatic bass and then back to the major for the cadence adds still new intensity."[11]

Many passages in Bach's religious works follow a similar expressive trajectory involving major and minor keys that may sometimes take on a symbolic significance. For example, David Humphreys (1983, p. 23) sees the "languishing chromatic inflections, syncopations and appoggiaturas" of the following episode from the St Anne Prelude for organ, BWV 552 from Clavier-Übung III as "showing Christ in his human aspect. Moreover the poignant angularity of the melody, and in particular the sudden turn to the minor, are obvious expressions of pathos, introduced as a portrayal of his Passion and crucifixion":[12]

Notably, Bach's two books of The Well-Tempered Clavier, composed in 1722 and 1744 respectively, differ considerably in their application of Picardy thirds, which occur unambiguously at the end of all of the minor-mode preludes and all but one of the minor-mode fugues in the first book.[13] In the second book, however, fourteen of the minor-mode movements end on a minor chord, or occasionally, on a unison.[14] Manuscripts vary in many of these cases.

While the device was used less frequently during the Classical era, examples can be found in works by Haydn and Mozart, such as the slow movement of Mozart's Piano Concerto 21, K. 467:

Philip Radcliffe says that the dissonant harmonies here "have a vivid foretaste of Schumann and the way they gently melt into the major key is equally prophetic of Schubert".[15] At the end of his opera Don Giovanni, Mozart uses the switch from minor to major to considerable dramatic effect: "As the Don disappears, screaming in agony, the orchestra settles in on a chord of D major. The change of mode offers no consolation, though: it is more like the tierce de Picardie, the 'Picardy third' (a famous misnomer derived from tierce picarte, 'sharp third'), the major chord that was used to end solemn organ preludes and toccatas in the minor keys in days of old."[16]

The fierce C minor drama that pervades the Allegro con brio ed appassionato movement from Beethoven's last Piano Sonata, Op. 111, dissipates as the prevailing tonality turns to the major in its closing bars "in conjunction with a concluding diminuendo to end the movement, somewhat unexpectedly, on a note of alleviation or relief".[17]

The switch from minor to major was a device used frequently and to great expressive effect by Schubert in both his songs and instrumental works. In his book on the song cycle Winterreise, singer Ian Bostridge speaks of the "quintessentially Schubertian effect in the final verse" of the opening song "Gute Nacht", "as the key shifts magically from minor to major".[18]

Susan Wollenberg describes how the first movement of Schubert's Fantasia in F minor for piano four-hands, D 940, "ends in an extended Tierce de Picardie".[19] The subtle change from minor to major occurs in the bass at the beginning of bar 103:

In the Romantic era, those of Chopin's nocturnes that are in a minor key almost always end with a Picardy third.[citation needed] A notable structural employment of this device occurs with the finale of the Tchaikovsky Fifth Symphony, where the motto theme makes its first appearance in the major mode.[citation needed]

Interpretation

[edit]According to James Bennighof: "Replacing an expected final minor chord with a major chord in this way is a centuries-old technique—the raised third of the chord, in this case G♯ rather than G natural,[verification needed] was first dubbed a 'Picardy third' (tierce de Picarde) in print by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in 1797 ... to express [the idea that] hopefulness might seem unremarkable, or even clichéd."[20]

Notable examples

[edit]- The Christian hymn tune "Picardy", often sung with the text "Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence", is based on a French carol from the 17th century or earlier. It is in a minor key, but the final chord is changed to major on the final verse.

- (Unknown) – "Coventry Carol" (written not later than 1591). Modern harmonisations of this carol include the famously distinctive finishing major Picardy third in the melody,[21] but the original 1591 harmonisation went much further with this device, including Picardy thirds at seven of the twelve tonic cadences notated, including all three such cadences in its chorus.[22]

- The Band – "This Wheel's On Fire", composed by Rick Danko and Bob Dylan, and appearing on both Music from Big Pink and The Basement Tapes, is in A minor and resolves to an A major chord at the end of the chorus.

- The Beatles – "I'll Be Back", from the soundtrack album of the film A Hard Day's Night. Ian MacDonald speaks of the way "Lennon is harmonised by McCartney in shifting major and minor thirds, resolving on a Picardy third at the end of the first and second verses".[23]

- Beethoven – Hammerklavier, slow movement[24]

- Brahms – Piano Trio No. 1, scherzo[25]

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart - Lacrimosa from Requiem in D Minor K.626 (Süssmayr completion) is in the tonic key of D minor, where the final cadence ends on a D Major chord.

- Sarah Connor – "From Sarah with Love", final cadence[26]

- Coots and Gillespie, "You Go to My Head". Ted Gioia describes the song as starting "in the major key, but from the second bar onward, Mr. Coots seems intent on creating a feverish dream quality tending more to the minor mode" before finally reaching a cadence in the major.[27]

- Dvořák – New World Symphony, finale[28]

- Bob Dylan – "Ain't Talkin'", the final song on Modern Times (2006), is played in E minor but ends (and ends the album) with a ringing E major chord.[29]

- Roberta Flack – "Killing Me Softly with His Song" ending and resolution. According to Flack: "My classical background made it possible for me to try a number of things with [the song's arrangement]. I changed parts of the chord structure and chose to end on a major chord. [The song] wasn't written that way."[30]

- Oliver Nelson – "Stolen Moments", from the 1961 album The Blues and the Abstract Truth; Ted Gioia sees "the brief resolve into the tonic major in bar four of the melody" as "a clever hook... one of the many interesting twists" in this jazz composition.[31]

- Joni Mitchell – "Tin Angel", from Clouds (1969); the Picardy third lands on the lyric "I found someone to love today". According to Katherine Monk, the Picardy third in this song, "suggests Mitchell is internally aware of romantic love's inability to provide true happiness but, gosh darn it, it's a nice illusion all the same."[32]

- Donna Summer – “I Feel Love” (1977) alternates throughout with an accompaniment of "synth swirls: major and minor; it’s basically a version of what Franz Schubert did for his whole career."[33]

- The Fireballs – "Vaquero", This (1961) Tex-Mex instrumental composed by George Tomsco and Norman Petty is clearly in the key of E minor, and yet ends with a ringing E Major chord."

- Hall & Oates – "Maneater"; each verse has a Picardy third in the middle, moving from a major seventh in the second measure to a flat second in the third measure, and finally ending on a major first in the fourth measure. In the song's original key of B minor, this is an A major chord to a C major chord, ending on a B major chord.

- The Turtles – "Happy Together" (1967) alternates between major and minor keys with the last chord of the outro featuring a Picardy third.

- The Zombies - "Time of the Season", from the 1968 album Odessey and Oracle, is in E minor with each chorus ending on an E major chord.

- Henryk Górecki's Symphony No. 3 op 36, also known as the Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, ends in a positive major third contrasting with the preceding greater part of the work.

- Pink Floyd's "Shine On You Crazy Diamond" concludes with a sudden switch to a major key.

- In The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, several ocarina songs end with a Picardy third. Specifically, all minor Ocarina songs that can be used to teleport to a temple end in the respective major chord (Bolero of Fire, Nocturne of Shadow and Requiem of Spirit). Serenade of Water is written in D dorian, and again ends in a D major chord, which makes for a "modal to major" example of the Picardy third.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Percy Scholes (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Music: Self-indexed and with a Pronouncing Glossary and Over 1,100 Portraits and Pictures, ninth edition, completely revised and reset and with many additions to text and illustrations (London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1955), pp. 1027–28.

- ^ "How Picard was the "Picardy Third"?". ProQuest. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ Peter Kivy, Osmin's Rage: Philosophical Reflections on Opera, Drama, and Text, with a New Final Chapter (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1999), p. 289. ISBN 978-0-8014-8589-3.

- ^ Deryck Cooke, The Language of Music (London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1959), p. 57.

- ^ Denise LaGiglia and Anna Belle O'Shea, The Liturgical Flutist: A Method Book and More (Chicago, Illinois: GIA Publications, 2005), p. 166. ISBN 978-1-57999-529-4.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Dictionnaire De Musique (Amsterdam: M. M. Rey, 1768), p.320. https://www.loc.gov/resource/muspre1800.101611/?sp=428.

- ^ Don Michael Randel (ed.), The Harvard Dictionary of Music (4th ed.) (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press, 2003), p. 660. ISBN 0-674-01163-5.

- ^ Robert A. Hall, Jr., "How Picard was the Picardy Third?", Current Musicology 19 (1975): pp. 78–80.

- ^ La Curne de Sainte-Palaye, J.B. (1882). Dictionnaire historique de l'ancien langage françois ou glossaire de l'ancien langage françois depuis son origine jusqu'au siècle de Louis XIV. Glossarium de Du Cange.

- ^ Bruce Benward and Marilyn Nadine Saker, Music in Theory and Practice: Volume II, eighth edition (Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2009), p. 74. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

- ^ Charles Rosen, Music and Sentiment (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010), p. 45.

- ^ Humphreys, D. (1983). The Esoteric structure of Bach's Clavierübung III, p. 25. University of Cardiff Press.

- ^ Butler, H. Joseph. "Emulation and Inspiration: J. S. Bach's Transcriptions from Vivaldi's L'estro armonico Archived 2015-11-29 at the Wayback Machine" (2011), p. 21.

- ^ Oxford Companion to Music, tenth edition, edited by Percy A. Scholes and John Owen Ward (London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1970).[full citation needed]

- ^ Radcliffe, P. (1978). Mozart Piano Concertos, p. 52. London: British Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Taruskin, R. (2010). The Oxford History of Western Music: Music in the seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries, p. 494. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Taruskin, R. (2010). The Oxford History of Western Music: Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, p. 730. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Ian Bostridge (2015). Schubert's Winter Journey, p. 7 London: Faber and Faber.

- ^ Wollenberg, S. (2011). Schubert's Fingerprints: Studies in the Instrumental Works, p. 42. London, Routledge.

- ^ James Bennighof, "The Words and Music of Joni Mitchell", Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2010.[page needed]

- ^ Coventry Carol Archived 2016-09-11 at the Wayback Machine at the Choral Public Domain Library. Accessed 2016-09-07.

- ^ Thomas Sharp, A Dissertation on the Pageants Or Dramatic Mysteries Anciently Performed at Coventry (Coventry: Merridew and Son, 1825), p. 116.

- ^ Ian MacDonald, Revolution in the Head: The Beatles Records and the Sixties (London: Pimlico, 2005): p. 119.

- ^ Robert S. Hatten, Musical Meaning in Beethoven: Markedness, Correlation, and Interpretation (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 39. ISBN 0-253-32742-3. First paperback reprint edition 2004. ISBN 978-0-253-21711-0.

- ^ Johannes Brahms, Complete Piano Trios ([full citation needed]: Dover Publications, 1926), [page needed]. ISBN 048625769X.

- ^ Walter Everett, "Pitch Down the Middle", in Expression in Pop-Rock Music, second edition, edited by[full citation needed] (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2008):[page needed]

- ^ Gioia, T. (2012). The Jazz Standards: A Guide to the Repertoire, p. 468. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Antonín Dvořák, Symphonies Nos. 8 and 9 (Dover Publications, 1984), pp. 257–258. ISBN 048624749X.

- ^ Østrem, Eyolf. "Ain't Talkin' | dylanchords". dylanchords.com.. The guitar part is played in Em with a capo on the 4th fret, so the song sounds in the key of G♯ minor.

- ^ Toby Cresswell, 1001 Songs (Pahran, Austria: Hardie Grant Books, 2005), p. 388, ISBN 978-1-74066-458-5.

- ^ Gioia, T. (2012, p.402), The Jazz Standards, Oxford University Press

- ^ Katherine Monk, Joni: The Creative Odyssey of Joni Mitchell (Vancouver: Greystone, 2012) p. 73. ISBN 9781553658375

- ^ Tom Service (2019) "Riffs, Loops and Ostinati", a programme in the series The Listening Service, BBC Radio 3, 27 January. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m00022nx Accessed 29 January 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Latham, Alison (ed.). 2002. "Tierce de Picardie (Fr., ‘Picardy 3rd’)". The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866212-9.

- Ruff, Lillian M. 1972. "Josquin Des Pres: Some Features of His Motets". The Consort: Annual Journal of the Dolmetsch Foundation 28:106–18.

- Rushton, Julian. 2001. "Tierce de Picardie [Picardy 3rd]". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Rutherford-Johnson, Tim, Michael Kennedy, and Joyce Bourne Kennedy (eds.). 2012. "Tierce de Picardie". The Oxford Dictionary of Music, sixth edition. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957810-8.

Picardy third

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Illustration

Definition

The Picardy third, also known as tierce de Picardie, is a harmonic convention in which a composition in a minor key concludes with a major tonic chord rather than the expected minor tonic, typically at the final authentic cadence.[2] This device involves raising the third degree of the minor scale by a semitone to form the major third in the tonic chord, creating an unexpected shift from the prevailing minor mode to a major resolution.[3] For instance, in a piece in C minor, the final chord alters from C–E♭–G (minor) to C–E–G (major).[6] The structure often appears in the progression from the dominant (V) to the tonic (i) in minor, where the final i becomes I through this modal mixture.[2] A basic notational example is the cadence i–V–i in a minor key, resolving instead to I, as the raised third provides closure by borrowing from the parallel major mode.[3] This differs from the Andalusian cadence, a repeating descending pattern (i–bVI–bVII–V) common in flamenco and popular music that does not necessarily conclude a piece, and the deceptive cadence, which unexpectedly resolves V to vi rather than to the tonic.[7] It was particularly prevalent in Renaissance and Baroque music.[6]Basic Illustration

The Picardy third refers to the use of a major tonic chord at the conclusion of a piece or section in a minor key.[2][8] A basic illustration appears in a simple four-bar phrase in C minor, where the expected minor tonic resolution is replaced by a major one. For instance, the progression might begin with a C minor chord (C–E♭–G), move to F minor (F–A♭–C) for subdominant function, then to G major (G–B–D) as the dominant, and conclude on a C major chord (C–E–G) instead of C minor. This alteration highlights the Picardy third through the raised third degree (E natural), creating an annotated final chord where the E♮ stands out against the prevailing minor tonality.[2][8] Auditorily, this shift introduces an unexpected brightness and sense of uplift at the conclusion, transforming the potentially somber minor resolution into a more affirmative close.[2][8] To compare, a non-Picardy ending in C minor would resolve the same progression to a C minor chord (C–E♭–G), maintaining the darker, introspective quality typical of the minor mode. In contrast, the Picardy version employs the major third (E–G), yielding a brighter, more consonant finale. The following side-by-side notation (in basic lead-sheet format) demonstrates this difference:| Measure | Non-Picardy (C minor ending) | Picardy Third (C major ending) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cm: C–E♭–G | Cm: C–E♭–G |

| 2 | Fm: F–A♭–C | Fm: F–A♭–C |

| 3 | G: G–B–D | G: G–B–D |

| 4 | Cm: C–E♭–G | C: C–E–G (E♮ accidental) |