Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Baking

View on Wikipedia

Baking is a method of preparing food that uses dry heat, typically in an oven, but it can also be done in hot ashes, or on hot stones. Bread is the most commonly baked item, but many other types of food can also be baked.[1] Heat is gradually transferred from the surface of cakes, cookies, and pieces of bread to their center, typically conducted at elevated temperatures surpassing 300 °F. Dry heat cooking imparts a distinctive richness to foods through the processes of caramelization and surface browning. As heat travels through, it transforms batters and doughs into baked goods and more with a firm dry crust and a softer center.[2] Baking can be combined with grilling to produce a hybrid barbecue variant by using both methods simultaneously, or one after the other. Baking is related to barbecuing because the concept of the masonry oven is similar to that of a smoke pit.

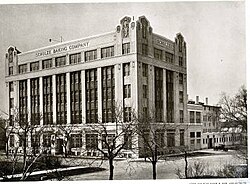

Baking has traditionally been performed at home for day-to-day meals and in bakeries and restaurants for local consumption. When production was industrialized, baking was automated by machines in large factories. The art of baking remains a fundamental skill and is important for nutrition, as baked goods, especially bread, are a common and important food, both from an economic and cultural point of view. A person who prepares baked goods as a profession is called a baker.

Foods and techniques

[edit]

All types of food can be baked, but some require special care and protection from direct heat. Various techniques have been developed to provide this protection.

In addition to bread, baking is used to prepare cakes, pastries, pies, tarts, quiches, cookies, scones, crackers, pretzels, and more. These popular items are known collectively as "baked goods," and are often sold at a bakery, which is a store that carries only baked goods, or at markets, grocery stores, farmers markets or through other venues.

Meats—including cured meats like ham—However, baking is typically reserved for meatloaf, smaller cuts of whole meat, or whole meats that are stuffed or coated with bread crumbs or buttermilk batter. Some foods are surrounded with moisture during baking by placing a small amount of liquid (such as water or broth) in the bottom of a closed pan, and letting it steam up around the food. Roasting is a term synonymous with baking, but traditionally denotes the cooking of whole animals or major cuts through exposure to dry heat; for instance, one bakes chicken parts but roasts the whole bird. One can bake pork or lamb chops but roasts the whole loin or leg. There are many exceptions to this rule of the two terms. Baking and roasting otherwise involve the same range of cooking times and temperatures. Another form of baking is the method known as en croûte (French for "in crust", referring to a pastry crust), which protects the food from direct heat and seals the natural juices inside. Meat, poultry, game, fish or vegetables can be prepared by baking en croûte. Well-known examples include Beef Wellington, where the beef is encased in pastry before baking; pâté en croûte, where the terrine is encased in pastry before baking; and the Vietnamese variant, a meat-filled pastry called pâté chaud. The en croûte method also allows meat to be baked by burying it in the embers of a fire—a favorite method of cooking venison. Salt can also be used to make a protective crust that is not eaten. Another method of protecting food from the heat while it is baking is to cook it en papillote (French for "in parchment"). In this method, the food is covered by baking paper (or aluminum foil) to protect it while it is being baked. The cooked parcel of food is sometimes served unopened, allowing diners to discover the contents for themselves.

Eggs can also be used in baking to produce savory or sweet dishes. In combination with dairy products especially cheese, they are often prepared as a dessert. For example, although a baked custard can be made using starch (in the form of flour, cornflour, arrowroot, or potato flour), the flavor of the dish is much more delicate if eggs are used as the thickening agent. Baked custards, such as crème caramel, are among the items that need protection from an oven's direct heat, and the bain-marie method serves this purpose. The cooking container is half-submerged in water in another, larger one so that the heat in the oven is more gently applied during the baking process. Baking a successful soufflé requires that the baking process be carefully controlled. The oven temperature must be absolutely even and the oven space must not be shared with another dish. These factors, along with the theatrical effect of an air-filled dessert, have given this baked food a reputation for being a culinary achievement. Similarly, a good baking technique (and a good oven) are also needed to create a baked Alaska because of the difficulty of baking hot meringue and cold ice cream at the same time. Baking can also be used to prepare other foods such as pizzas, baked potatoes, baked apples, baked beans, some casseroles and pasta dishes such as lasagne.

Baking can also be used to prepare other foods such as pizzas, baked potatoes, baked apples, baked beans, some casseroles and pasta dishes such as lasagne. Baking goods are not limited to being served warm or right after baking, however, as some recipes, such as cheesecake, are served differently. Specifically, cheesecake requires cooling after being removed from the oven, before then being set to freeze inside of a refrigerator for several hours, and finally served cold.

Baking in ancient times

[edit]

The earliest known form of baking occurred when humans took wild grass grains, soaked them in water, and mashed the mixture into a kind of broth-like paste.[3] The paste was cooked by pouring it onto a flat, hot rock, resulting in a bread-like substance. Later, as humans mastered fire, they roasted the paste on hot embers, making bread-making more convenient as it could be done whenever fire was created. According to Britannica, the Ancient Egyptians invented the first ovens.[4] They also baked bread using yeast, which they had previously been using to brew beer.[5] By 2600 BCE, they were making bread in ways similar in principle to those of today.[4] The book Bread for the Wilderness states that "Ovens and worktables have been discovered in archaeological digs from Turkey (Hacilar) to Palestine (Jericho (Tell es-Sultan)) and date back to 5600 BC."[6]

Baking flourished during the Roman Empire. Beginning around 300 BC, the pastry cook became an occupation for Romans (known as the pastillarium) and became a respected profession because pastries were considered decadent, and Romans loved festivity and celebration. Thus, pastries were often cooked especially for large banquets, and any pastry cook who could invent new types of tasty treats was highly prized. Around 1 AD, there were more than three hundred pastry chefs in Rome, and Cato wrote about how they created all sorts of diverse foods and flourished professionally and socially because of their creations. Cato speaks of an enormous number of breads including; libum (cakes made with flour and honey, often sacrificed to gods[7]), placenta (groats and cress),[8] spira (modern day flour pretzels), scibilata (tortes), savillum (sweet cake), and globus apherica (fritters). A great selection of these, with many different variations, different ingredients, and varied patterns, were often found at banquets and dining halls. The Romans baked bread in an oven with its own chimney, and had mills to grind grain into flour. A bakers' guild was established in 168 BC in Rome.[5]

Commercial baking

[edit]

Eventually, the Roman art of baking became known throughout Europe and eventually spread to eastern parts of Asia.[9] By the 13th century in London, commercial trading, including baking, had many regulations attached. In the case of food, they were designed to create a system "so there was little possibility of false measures, adulterated food or shoddy manufactures". There were by that time twenty regulations applying to bakers alone, including that every baker had to have "the impression of his seal" upon bread.[10]

Beginning in the 19th century, alternative leavening agents became more common, such as baking soda.[5] Bakers often baked goods at home and then sold them in the streets. This scene was so common that Rembrandt, among others, painted a pastry chef selling pancakes in the streets of Germany, with children clamoring for a sample. In London, pastry chefs sold their goods from handcarts. This developed into a delivery system of baked goods to households and greatly increased demand as a result. In Paris, the first open-air café of baked goods was developed, and baking became an established art throughout the entire world.[11]

Every family used to prepare the bread for its own consumption, the trade of baking, not having yet taken shape.

Mrs Beeton (1861)[12]

Baking eventually developed into a commercial industry using automated machinery which enabled more goods to be produced for widespread distribution. In the United States, the baking industry "was built on marketing methods used during feudal times and production techniques developed by the Romans."[13] Some makers of snacks such as potato chips or crisps have produced baked versions of their snack products as an alternative to the usual cooking method of deep frying in an attempt to reduce their calorie or fat content. Baking has opened up doors to businesses such as cake shops and factories where the baking process is done with larger amounts in large, open furnaces.[citation needed]

The aroma and texture of baked goods as they come out of the oven are strongly appealing but is a quality that is quickly lost. Since the flavour and appeal largely depend on freshness, commercial producers have to compensate by using food additives as well as imaginative labeling. As more and more baked goods are purchased from commercial suppliers, producers try to capture that original appeal by adding the label "home-baked." Such attempts seek to make an emotional link to the remembered freshness of baked goods as well as to attach positive associations the purchaser has with the idea of "home" to the bought product. Freshness is such an important quality that restaurants, although they are commercial (and not domestic) preparers of food, bake their own products. For example, scones at The Ritz London Hotel "are not baked until early afternoon on the day they are to be served, to make sure they are as fresh as possible."[14]

Equipment

[edit]

Baking needs an enclosed space for heating – typically in an oven. Formerly, primitive clay ovens were in use. The fuel can be supplied by wood, coal, gas, or electricity. Adding and removing items from an oven may be done by hand with an oven mitt or by a peel, a long handled tool specifically used for that purpose.

Many commercial ovens are equipped with two heating elements: one for baking, using convection and thermal conduction to heat the food, and one for broiling or grilling, heating mainly by radiation. Another piece of equipment still used for baking is the Dutch oven. "Also called a bake kettle, bastable, bread oven, fire pan, bake oven kail pot, tin kitchen, roasting kitchen, doufeu (French: "gentle fire") or feu de compagne (French: "country oven") [it] originally replaced the cooking jack as the latest fireside cooking technology," combining "the convenience of pot-oven and hangover oven."[15]

Asian cultures have adopted steam baskets to produce the effect of baking while reducing the amount of fat needed.[16]

Other equipment/tools needed for baking precision include a method for measuring ingredients. Ideally, a scale accurate to the gram is used, as exact measurements provide the best results, but some bakers rely on measuring cups and measuring spoons.[17][18]

Digital kitchen scales are also popular in baking where precise measurements are a must for dry ingredients.[19] The tare function simplifies the process by allowing multiple ingredients to be measured in the same mixing bowl, resetting the scale to zero between each addition and eliminating the need for extra measuring tools.[20]

Process

[edit]

Eleven events occur concurrently during baking, some of which (such as starch gelatinization) would not occur at room temperature.[21]

- Fats melt

- Gases form and expand

- Microorganisms die

- Sugar dissolves

- Egg, milk, and gluten proteins coagulate

- Starches gelatinize or solidify

- Liquids evaporate

- Caramelization and Maillard browning occur on crust

- Enzymes are denatured

- Changes occur to nutrients

- Pectin breaks down[22]

The dry heat of baking changes the form of starches in the food and causes its outer surfaces to brown, giving it an attractive appearance and taste. The browning is caused by the caramelization of sugars and the Maillard reaction. Maillard browning occurs when "sugars break down in the presence of proteins. Because foods contain many different types of sugars and proteins, Maillard browning contributes to the flavour of a wide range of foods, including nuts, roast beef, and baked bread."[23] The moisture is never entirely "sealed in"; over time, an item being baked will become dry. This is often an advantage, especially in situations where drying is the desired outcome, like drying herbs or roasting certain types of vegetables.

The baking process does not require any fat to be used to cook in an oven. When baking, consideration must be given to the amount of fat that is contained in the food item. Higher levels of fat such as margarine, butter, lard, or vegetable shortening will cause an item to spread out during the baking process.

With the passage of time, breads harden and become stale. This is not primarily due to moisture being lost from the baked products, but more a reorganization of the way in which the water and starch are associated over time. This process is similar to recrystallization and is promoted by storage at cool temperatures, such as in a domestic refrigerator or freezer.

Cultural and religious significance

[edit]

Baking, especially of bread, holds special significance for many cultures. It is such a fundamental part of everyday food consumption that the children's nursery rhyme Pat-a-cake, pat-a-cake, baker's man takes baking as its subject. Baked goods are normally served at all kinds of parties and special attention is given to their quality at formal events. They are also one of the main components of a tea party, including at nursery teas and high teas, a tradition which started in Victorian Britain, reportedly when Anna Russell, Duchess of Bedford "grew tired of the sinking feeling which afflicted her every afternoon round 4 o'clock ... In 1840, she plucked up courage and asked for a tray of tea, bread and butter, and cake to be brought to her room. Once she had formed the habit she found she could not break it, so spread it among her friends instead. As the century progressed, afternoon tea became increasingly elaborate."[24]

The Benedictine Sisters of the Benedictine Monastery of Caltanissetta baked a pastry called Crocetta of Caltanissetta (Cross of Caltanissetta). They used to be prepared for the Holy Crucifix festivity. The monastery was situated next to the Church of the Holy Cross, from which these sweet pastries take the name.

For Jews, matzo is a baked product of considerable religious and ritual significance. Baked matzah bread can be ground up and used in other dishes, such as gefilte fish, and baked again. For Christians, bread has to be baked to be used as an essential component of the sacrament of the Eucharist. In the Eastern Christian tradition, baked bread in the form of birds is given to children to carry to the fields in a spring ceremony that celebrates the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste.[25]

Jesus defines himself as the “bread of life” (John 6:35). Divine “Grace” is called “bread of the strong” and preaching, religious teaching, the “bread of the word of God”. In Roman Catholicism, the piece of blessed wax encased in a reliquary is the “sacred bread”. In Hebrew, Bethlehem means "the house of bread", and Christians see in the fact that Jesus was born (before moving to Nazareth) in a city of that name, the significance of his sacrifice via the Eucharist. The Eucharist is often interpreted as a connection to the Holy Spirit, a symbol of God’s love, and an invitation to reflect that love in service to others, providing strength for living out one’s faith.[26]

See also

[edit]

References

[edit]- ^ "60 Baking Recipes We Stole From Grandma". Taste of Home. Archived from the original on 2018-10-19. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- ^ Figoni, Paula I. (2011). How Baking Works: Exploring the Fundamentals of Baking Science (3rd ed.). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-39813-5.p.38

- ^ Pfister, Fred. "Pfister Consulting: History of Baking – How Did It All Start? Yes people". Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ a b "Baking". Britannica. Retrieved 2024-11-10.

- ^ a b c Morgan, James (2012). Culinary Creation. Routledge. pp. 297–298. ISBN 978-1-136-41270-7.

- ^ Rochelle, Jay Cooper (2001). Bread for the Wilderness: Baking As Spiritual Craft. Fairfax, VA: Xulon Press. p. 32. ISBN 1-931232-52-0.

- ^ Lewis & Short (1879). "lībum". A Latin Dictionary – via Logeion.

- ^ Kearns, Emily (1996). "cakes". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony (eds.). Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 272.

Cakes [...] were given many names in Greek and Latin, of which the most general were πέμματα, πόπανα, liba (sacrificial cakes), and placentae (from πλακοῦντες). [...] Most were regarded as a luxurious delicacy, to be eaten with fruit after the main course at a special meal. Cakes were also very commonly used in sacrifice, either as a peripheral accompaniment to the animal victim or as a bloodless sacrifice.

- ^ Tracy (2017-06-27). "Baked with love". Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ Peter Ackroyd (2003). London: the biography (1st Anchor Books ed.). New York: Anchor books. p. 59. ISBN 0385497717.

- ^ "The History of Bread 2". www.dovesfarm.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2021-04-24. Retrieved 2021-04-24.

- ^ Beeton, Mrs (1861). Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management (Facsimile edition, 1968 ed.). London: S.O. Beeton, 18 Bouverie St. E.C. p. 831. ISBN 0-224-61473-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Bessie Emrick Whitten (1990). David O. Whitten (ed.). Handbook of American Business History: Manufacturing. Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-25198-3.p.53

- ^ Simpson, Helen (1986). The London Ritz Book of Afternoon Tea - The Art & Pleasures of Taking Tea. London, UK: Angus & Robertson, Publishers. p. 8. ISBN 0-207-15415-5.

- ^ Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2004). Encyclopedia of Kitchen History. Taylor & Francis Books. p. 330. ISBN 0-203-31917-6.

- ^ "Chinese steamed sponge cake (ji dan gao)". Chinese Grandma. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ^ Lopez-Alt, J. Kenji (10 August 2018). "Ounces and Grams: Why Mass Is Not the Best Way to List Ingredients". Serious Eats. Retrieved 2024-08-14.

- ^ Beck, Andrea. "21 Baking Tools Every Home Cook Needs (Plus 16 Handy Extras)". Better Homes & Gardens. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ Kathan, Scott. "How to Carefully Measure Ingredients". Americas Test Kitchen. Wikipedia. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ Shannon, Kate; Sandler, Sarah (August 21, 2024). "The Best Kitchen Scales". America’s Test Kitchen.

- ^ Figoni 2011, p. 38.

- ^ Figoni 2011, ch.3 pp.38 ff.

- ^ Figoni 2011, p. 42.

- ^ Simpson, Helen (1986). The London Ritz Book of Afternoon Tea: The Art & Pleasures of Making Tea. London: Angus & Robertson Publishers. p. 16. ISBN 0-207-15415-5.

- ^ "Lark Buns (Zhavoronki) Recipe for the 40 Martyrs of Sebaste - St. Nektarios Orthodox Church of Lenoir City, TN | Bun, Lenoir city, Orthodox". Pinterest. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- ^ Stadulis, Janet K.; Lahiff, Maureen; Wiltse, Lydia; Assero, Nancy; Mannion, James-Patrick; Laughlin, Gabe; de Nolasco, Iliana; Engels, Aaron (July 2024). "What Does the Eucharist Mean to You?". U.S. Catholic. 89 (7): 33. ISSN 0041-7548.

Bibliography

[edit]- Burnett, John. "The baking industry in the nineteenth century." Business History 5.2 (1963): 98-108. in Britain.

- Figoni, Paula (2010). How Baking Works: Exploring the Fundamentals of Baking Science (3 ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0470392676.—a textbook on baking and setting up a bakery

- Laudan, Rachel. Cuisine and empire: Cooking in world history (Univ of California Press, 2013) online.

- Pasqualone, Antonella. "Traditional flat breads spread from the Fertile Crescent: Production process and history of baking systems." Journal of Ethnic Foods 5.1 (2018): 10-19. online

- Pyler, E.J.; Gorton, L.A. (2008). Baking Science & Technology (PDF). Sosland Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-9820239-0-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-02-19. Retrieved 2013-01-23.

- Sharpless, Rebecca. Grain and Fire: A History of Baking in the American South (University of North Carolina Press, 2022) online scholarly review

- Ysewijn, R. (2020). Oats in the North, Wheat from the South: The History of British Baking: Savoury and Sweet. Australia: Murdoch Books Pty Limited.

- Zanoni, Bruno, C. Peri, and Sauro Pierucci. "A study of the bread-baking process. I: A phenomenological model." Journal of food engineering 19.4 (1993): 389-398.

External links

[edit]Baking

View on GrokipediaHistory of Baking

Origins in Ancient Civilizations

The earliest known evidence of baking dates to approximately 14,000 years ago, with charred remains of flatbread-like products discovered at the Shubayqa 1 site in northeastern Jordan, associated with the Natufian hunter-gatherer culture. These artifacts, analyzed through archaeobotanical methods, consisted of unleavened flatbreads made from wild cereals such as wheat and barley, combined with tubers and club-rush seeds, likely prepared over hearths rather than dedicated ovens.[12] This predates the advent of agriculture by about 4,000 years and represents the oldest direct evidence of bread-making, highlighting early experimentation with grinding and heat-processing plant foods for improved digestibility and nutrition.[13] In ancient Mesopotamia, baking advanced significantly by around 3000 BCE with the widespread use of tannurs, cylindrical clay ovens that allowed for efficient baking of flatbreads by adhering dough to the hot inner walls. These ovens, originating in the Fertile Crescent during the Neolithic period but refined in Sumerian and Akkadian societies, facilitated both household and communal production, often fueled by wood or dung.[14] Baking became integral to daily life and ritual, with evidence from cuneiform texts and archaeological sites like Ur indicating breads made from emmer wheat and barley flours.[15] Ancient Egypt further innovated baking practices around the same period, developing leavened bread through the incidental capture of wild yeasts during beer production, which was then applied to dough for rising. By 3000 BCE, Egyptians baked in clay molds or pots set in hot ashes, producing a staple food consumed by all social classes, from laborers paid in bread rations to temple offerings.[16] This leavening technique marked a key advancement, yielding lighter, more nutritious loaves from emmer wheat, and was depicted in tomb reliefs showing organized bakery operations.[17] The Greeks and Romans built upon these foundations, introducing more sophisticated domed ovens known as fornus in Roman times, which improved heat distribution for baking a variety of goods by the 5th century BCE. Greek bakers, influenced by Eastern techniques, popularized sourdough starters—natural fermentations of flour and water—for consistent leavening in everyday breads.[18] Romans expanded this with commercial bakeries and innovations like the placenta, a layered pastry resembling early cheesecakes, filled with cheese and honey, as described in Cato the Elder's recipes from the 2nd century BCE.[19] These developments laid the groundwork for baking's evolution into medieval Europe.Evolution Through Medieval and Industrial Eras

In medieval Europe, bakers' guilds emerged in the 12th century to safeguard professional standards, regulate bread pricing and quality, and ensure fair market access for members.[20] These organizations, such as those in France and England, also protected bakers from economic hardships by maintaining grain supplies during shortages and enforcing weights and measures for loaves.[21] Baking relied on communal stone ovens, constructed from durable materials like stone, clay, or brick, which were often owned by feudal lords or villages and heated with wood for efficient, high-heat baking of multiple batches.[22] These ovens allowed for the production of varied breads, from coarse rye loaves for peasants to refined white wheat bread reserved for nobility, symbolizing status as physicians praised its digestibility and purity over darker, bran-heavy varieties.[23][24] During the Renaissance, expanded trade routes from Asia and the New World introduced affordable sugar—initially classified as a spice—and exotic flavors like cinnamon, ginger, and cloves, transforming European baking toward sweeter, enriched doughs and early pastries.[25] Italian and French bakers incorporated these into items like marchpane (marzipan) and spiced buns, elevating confections from medicinal treats to luxurious staples at noble courts.[26] The Industrial Revolution marked a shift to mechanized production, with the development of hand-operated mechanical dough mixers around 1840 enabling faster, larger-scale kneading in emerging commercial settings.[27] Louis Pasteur's 1857 research on alcoholic fermentation identified yeast as a living microorganism responsible for rising dough, paving the way for standardized, pure yeast cultures that improved consistency in breadmaking.[28] The mid-19th century also saw the invention of chemical leaveners, such as baking powder developed by Alfred Bird in 1843 and further refined in the 1850s, which provided a quick and reliable alternative to yeast for rising doughs, revolutionizing both home and commercial baking.[6] Urbanization fueled the rise of commercial bakeries in 19th-century cities like London and New York, where factories produced uniform loaves for growing populations unable to bake at home.[29] In the United States, early examples included Boston's expanding bakery trade by the early 1800s, supporting daily bread needs amid immigration and factory work.[30] Railroads revolutionized ingredient distribution in the mid-19th century, transporting wheat, flour, and yeast from rural mills to urban centers at lower costs and faster speeds, enabling year-round baking and wider availability of refined goods.[31] This infrastructure boom, coupled with steam-powered ovens, scaled production and democratized access to quality baked items beyond elite circles.[32]Science and Principles of Baking

Chemical Reactions in Baking

Baking involves a series of chemical reactions that transform raw ingredients into structured, flavorful products, primarily through interactions between proteins, starches, sugars, and leavening agents. These reactions occur as heat is applied, leading to structural changes, gas production, and flavor development essential for texture and taste. Key processes include protein coagulation, starch modification, gas generation from leavening, and network formation in dough components. The Maillard reaction is a non-enzymatic browning process that develops color and complex flavors in baked goods, occurring between amino acids from proteins and reducing sugars when heated above 140°C (284°F). This reaction produces melanoidins, responsible for the golden-brown crust on bread and pastries, along with volatile compounds that contribute nutty, roasted aromas. The simplified reaction can be represented as: During baking, protein denaturation begins around 60-80°C (140-176°F), where heat causes proteins in flour and eggs to unfold and coagulate, forming a solid matrix that sets the structure of cakes, cookies, and breads. Concurrently, starch gelatinization occurs at 60-70°C (140-158°F), as starch granules in flour absorb water, swell, and rupture, creating a gel that binds moisture and contributes to tenderness and volume. These overlapping processes stabilize the product as temperatures rise, preventing collapse. Leavening reactions produce gases that create lift and aeration. In yeast fermentation, Saccharomyces cerevisiae converts glucose into carbon dioxide and ethanol through anaerobic respiration, with the equation: This CO₂ expands trapped air pockets in dough, yielding light crumb structure in breads. Chemical leavening, such as with baking soda (sodium bicarbonate), reacts with acids (e.g., from buttermilk or cream of tartar) to release CO₂ rapidly: This immediate gas production suits quick breads and muffins, enhancing volume without prolonged rising. Gluten network formation initiates during dough mixing, as hydration and mechanical shear align gliadin and glutenin proteins in wheat flour, forming disulfide bonds and a viscoelastic matrix that traps gases and provides elasticity. This three-dimensional structure, strengthened by kneading, determines the chewiness and shape retention in yeasted products like loaves and rolls.Role of Heat and Temperature

Heat plays a pivotal role in baking by facilitating physical transformations in dough and batter, such as expansion, structure setting, and moisture management, which ultimately determine the texture, volume, and quality of baked goods.[33] In conventional ovens, heat is transferred to the product through three primary modes: conduction, convection, and radiation. Conduction occurs directly through contact, as when heat from a metal pan transfers to the base of a loaf, promoting even bottom crust formation.[34] Convection involves the circulation of hot air currents within the oven, which evenly distributes heat around the product and enhances uniform rising, particularly in larger batches.[35] Radiation, emitted from heating elements or oven walls, provides direct surface heating that contributes to browning and crust development.[33] Precise temperature control is essential across baking stages to optimize outcomes. During proofing, yeast doughs are typically maintained at 24-27°C (75-81°F) to promote steady fermentation and gas production for optimal rise without over-fermentation.[36] Ovens are preheated to 180-220°C (356-428°F) to initiate strong oven spring, where rapid heat causes trapped gases to expand, increasing loaf volume significantly in the first 10-15 minutes of baking.[37] As baking progresses, the internal temperature of bread reaches 88–99°C (190–210°F) at the core to indicate doneness, depending on the type of bread, ensuring starch gelatinization and protein coagulation while preserving moisture.[38] Improper temperature management can significantly alter final texture. Overbaking at excessively high temperatures or prolonged times accelerates moisture evaporation, resulting in dry, tough crumb as water content drops below 30-35%, diminishing tenderness. Conversely, underbaking fails to fully gelatinize starches, which typically requires sustained heat above 60-70°C, leading to a gummy, dense interior due to unabsorbed moisture and incomplete structure setting. These effects underscore the need for monitoring, as heat not only drives physical changes but also briefly triggers surface reactions like Maillard browning for flavor and color.[33]Ingredients in Baking

Flours, Grains, and Base Components

Flours and grains serve as the foundational structural components in baking, providing the matrix that holds together baked goods through their starch and protein networks. Wheat flour, derived from grinding wheat kernels, is the most commonly used base due to its unique ability to form gluten, a viscoelastic protein structure that imparts elasticity and strength to doughs. The protein content in wheat flour, primarily gliadin and glutenin, directly influences this gluten development, with higher levels promoting stronger, chewier textures suitable for breads and lower levels yielding tender crumbs in cakes.[39][40] Wheat flours are categorized by protein content and milling fineness to suit specific baking needs. All-purpose flour, a blend of hard and soft wheats, typically contains 10-12% protein, making it versatile for a range of products like cookies, muffins, and quick breads where moderate structure is desired. Bread flour, milled from high-protein hard spring or winter wheats, has 12-14% protein to develop robust gluten networks essential for yeast-leavened loaves that require high elasticity and volume. In contrast, cake flour from soft wheats offers 6-8% protein for delicate, tender results in cakes and pastries, as the lower gluten formation prevents toughness.[41][40][42] Milling processes significantly affect flour texture, flavor, and nutrient profile. Stone-ground milling, a traditional method using rotating stones to crush whole kernels, preserves more bran, germ, and endosperm integrity, resulting in coarser particles with a nutty flavor and higher nutrient retention ideal for rustic breads. Roller milling, the modern industrial standard, employs sequential steel rollers to separate and refine the endosperm from bran and germ, producing finer, whiter flours with uniform particle size but potentially less flavor complexity unless whole streams are recombined. Stone milling generates more heat, which can degrade some heat-sensitive nutrients, while roller milling allows better control for enriched flours.[43][44][45] Alternative grains expand baking options, particularly for gluten-free or flavor-varied products, though they often require blending to mimic wheat's properties. Rye flour, with lower gluten potential than wheat (around 7-10% protein), imparts an acidic, earthy tang and denser crumb, commonly used in sourdough rye breads where its pentosans enhance water absorption for moist textures. Cornmeal, ground from dried corn kernels, lacks gluten entirely and provides a gritty, sweet profile suited for cornbreads and polenta-based bakes, contributing to crumbly structures. Rice flour, finely milled from white or brown rice, is naturally gluten-free with a neutral taste and fine texture, making it a staple in gluten-free baking for airy cakes and cookies when combined with binders.[46][47][48] Key properties of flours determine their baking performance. Protein content governs dough elasticity and gas retention, with higher levels (e.g., in bread flour) forming stronger networks for risen structures. Ash content, the mineral residue after incineration, reflects the inclusion of bran and germ; lower ash (0.4-0.6% in refined flours) indicates whiter, more extracted products, while higher ash (above 1%) in whole grain flours signals greater mineral density like magnesium and iron. Water absorption capacity, typically 58-62% of flour weight for bread doughs, arises mainly from proteins absorbing up to twice their weight in water, influencing dough hydration and final texture.[39][49][50] Proper storage and measurement ensure consistent results. Flour should be kept in airtight containers in a cool, dry place to prevent moisture absorption and pest infestation, with whole grain varieties refrigerated to slow rancidity from natural oils. For measurement, weighing in grams is preferred over volume cups for precision, as a cup of all-purpose flour weighs about 120-140 grams depending on packing. Sifting aerates compacted flour, reducing density by 20-30% and incorporating air for lighter batters, but it should follow measuring unless specified otherwise to avoid under-flouring.[51][52][53]| Flour Type | Protein Content (%) | Primary Use | Key Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-Purpose | 10-12 | Versatile (cookies, muffins, breads) | Balanced gluten for moderate structure[40] |

| Bread | 12-14 | Yeast breads | High elasticity from strong gluten[41] |

| Cake | 6-8 | Cakes, pastries | Low gluten for tenderness[42] |

| Rye | 7-10 | Rye breads | Acidic flavor, high absorption[46] |

| Cornmeal | 7-10 (no gluten) | Cornbread | Gritty texture, sweetness[47][54] |

| Rice | 6-8 (gluten-free) | Gluten-free goods | Fine, neutral for light crumb[48][55] |