Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Balancing selection

View on WikipediaBalancing selection refers to a number of selective processes by which multiple alleles (different versions of a gene) are actively maintained in the gene pool of a population at frequencies larger than expected from genetic drift alone. Balancing selection is rare compared to purifying selection.[1] It can occur by various mechanisms, in particular, when the heterozygotes for the alleles under consideration have a higher fitness than the homozygote.[2] In this way genetic polymorphism is conserved.[3]

Evidence for balancing selection can be found in the number of alleles in a population which are maintained above mutation rate frequencies. All modern research has shown that this significant genetic variation is ubiquitous in panmictic populations.

There are several mechanisms (which are not exclusive within any given population) by which balancing selection works to maintain polymorphism. The two major and most studied are heterozygote advantage and frequency-dependent selection.

Mechanisms

[edit]Heterozygote advantage

[edit]

In heterozygote advantage, or heterotic balancing selection, an individual who is heterozygous at a particular gene locus has a greater fitness than a homozygous individual. Polymorphisms maintained by this mechanism are balanced polymorphisms.[4] Due to unexpected high frequencies of heterozygotes, and an elevated level of heterozygote fitness, heterozygotic advantage may also be called "overdominance" in some literature.

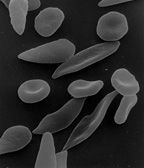

A well-studied case is that of sickle cell anemia in humans, a hereditary disease that damages red blood cells. Sickle cell anemia is caused by the inheritance of an allele (HgbS) of the hemoglobin gene from both parents. In such individuals, the hemoglobin in red blood cells is extremely sensitive to oxygen deprivation, which results in shorter life expectancy. A person who inherits the sickle cell gene from one parent and a normal hemoglobin allele (HgbA) from the other, has a normal life expectancy. However, these heterozygote individuals, known as carriers of the sickle cell trait, may suffer problems from time to time.

The heterozygote is resistant to the malarial parasite which kills a large number of people each year. This is an example of balancing selection between the fierce selection against homozygous sickle-cell sufferers, and the selection against the standard HgbA homozygotes by malaria. The heterozygote has a permanent advantage (a higher fitness) wherever malaria exists.[5][6] Maintenance of the HgbS allele through positive selection is supported by significant evidence that heterozygotes have decreased fitness in regions where malaria is not prevalent. In Surinam, for example, the allele is maintained in the gene pools of descendants of African slaves, as the Surinam suffers from perennial malaria outbreaks. Curacao, however, which also has a significant population of individuals descending from African slaves, lacks the presence of widespread malaria, and therefore also lacks the selective pressure to maintain the HgbS allele. In Curacao, the HgbS allele has decreased in frequency over the past 300 years, and will eventually be lost from the gene pool due to heterozygote disadvantage.[7]

Frequency-dependent selection

[edit]Frequency-dependent selection occurs when the fitness of a phenotype is dependent on its frequency relative to other phenotypes in a given population. In positive frequency-dependent selection the fitness of a phenotype increases as it becomes more common. In negative frequency-dependent selection the fitness of a phenotype decreases as it becomes more common. For example, in prey switching, rare morphs of prey are actually fitter due to predators concentrating on the more frequent morphs. As predation drives the demographic frequencies of the common morph of prey down, the once rare morph of prey becomes the more common morph. Thus, the morph of advantage now is the morph of disadvantage. This may lead to boom and bust cycles of prey morphs. Host-parasite interactions may also drive negative frequency-dependent selection, in alignment with the Red Queen hypothesis. For example, parasitism of freshwater New Zealand snail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum) by the trematode Microphallus sp. results in decreasing frequencies of the most commonly hosted genotypes across several generations. The more common a genotype became in a generation, the more vulnerable to parasitism by Microphallus sp. it became.[8] Note that in these examples that no one phenotypic morph, nor one genotype is entirely extinguished from a population, nor is one phenotypic morph nor genotype selected for fixation. Thus, polymorphism is maintained by negative frequency-dependent selection.

Fitness varies in time and space

[edit]The fitness of a genotype may vary greatly between larval and adult stages, or between parts of a habitat range.[9] Variation over time, unlike variation over space, is not in itself enough to maintain multiple types, because in general the type with the highest geometric mean fitness will take over, but there are a number of mechanisms that make stable coexistence possible.[10]

More complex examples

[edit]Species in their natural habitat are often far more complex than the typical textbook examples.

Grove snail

[edit]The grove snail, Cepaea nemoralis, is famous for the rich polymorphism of its shell. The system is controlled by a series of multiple alleles. Unbanded is the top dominant trait, and the forms of banding are controlled by modifier genes (see epistasis).

In England the snail is regularly preyed upon by the song thrush Turdus philomelos, which breaks them open on thrush anvils (large stones). Here fragments accumulate, permitting researchers to analyse the snails taken. The thrushes hunt by sight, and capture selectively those forms which match the habitat least well. Snail colonies are found in woodland, hedgerows and grassland, and the predation determines the proportion of phenotypes (morphs) found in each colony.

A second kind of selection also operates on the snail, whereby certain heterozygotes have a physiological advantage over the homozygotes. Thirdly, apostatic selection is likely, with the birds preferentially taking the most common morph. This is the 'search pattern' effect, where a predominantly visual predator persists in targeting the morph which gave a good result, even though other morphs are available.

The polymorphism survives in almost all habitats, though the proportions of morphs varies considerably. The alleles controlling the polymorphism form a supergene with linkage so close as to be nearly absolute. This control saves the population from a high proportion of undesirable recombinants.

In this species predation by birds appears to be the main (but not the only) selective force driving the polymorphism. The snails live on heterogeneous backgrounds, and thrush are adept at detecting poor matches. The inheritance of physiological and cryptic diversity is preserved also by heterozygous advantage in the supergene.[11][12][13][14][15] Recent work has included the effect of shell colour on thermoregulation,[16] and a wider selection of possible genetic influences is also considered.[17]

Chromosome polymorphism in Drosophila

[edit]In the 1930s Theodosius Dobzhansky and his co-workers collected Drosophila pseudoobscura and D. persimilis from wild populations in California and neighbouring states. Using Painter's technique,[18] they studied the polytene chromosomes and discovered that all the wild populations were polymorphic for chromosomal inversions. All the flies look alike whatever inversions they carry, so this is an example of a cryptic polymorphism. Evidence accumulated to show that natural selection was responsible:

- Values for heterozygote inversions of the third chromosome were often much higher than they should be under the null assumption: if no advantage for any form the number of heterozygotes should conform to Ns (number in sample) = p2+2pq+q2 where 2pq is the number of heterozygotes (see Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium).

- Using a method invented by L'Heretier and Teissier, Dobzhansky bred populations in population cages, which enabled feeding, breeding and sampling whilst preventing escape. This had the benefit of eliminating migration as a possible explanation of the results. Stocks containing inversions at a known initial frequency can be maintained in controlled conditions. It was found that the various chromosome types do not fluctuate at random, as they would if selectively neutral, but adjust to certain frequencies at which they become stabilised.

- Different proportions of chromosome morphs were found in different areas. There is, for example, a polymorph-ratio cline in D. robusta along an 18-mile (29 km) transect near Gatlinburg, TN passing from 1,000 feet (300 m) to 4,000 feet.[19] Also, the same areas sampled at different times of year yielded significant differences in the proportions of forms. This indicates a regular cycle of changes which adjust the population to the seasonal conditions. For these results selection is by far the most likely explanation.

- Lastly, morphs cannot be maintained at the high levels found simply by mutation, nor is drift a possible explanation when population numbers are high.

By 1951 Dobzhansky was persuaded that the chromosome morphs were being maintained in the population by the selective advantage of the heterozygotes, as with most polymorphisms.[20][21][22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Charlesworth, Deborah; Willis, John H. (November 2009). "The genetics of inbreeding depression". Nature Reviews Genetics. 10 (11): 783–796. doi:10.1038/nrg2664. ISSN 1471-0064. PMID 19834483. S2CID 771357.

- ^ King, R.C.; Stansfield, W.D.; Mulligan, P.K. (2006). A dictionary of genetics (7th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 44.

- ^ Ford, E.B. (1940). "Polymorphism and taxonomy". In J. Huxley (ed.). The New Systematics. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 493–513.

- ^ Heredity. 2009. Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago.

- ^ Allison A.C. 1956. The sickle-cell and Haemoglobin C genes in some African populations. Ann. Human Genet. 21, 67-89.

- ^ Sickle cell anemia. 2009. Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago.

- ^ David Wool. 2006. The Driving Forces of Evolution: Genetic Processes in Populations. 80-82.

- ^ Koskella, B. and Lively, C. M. (2009), EVIDENCE FOR NEGATIVE FREQUENCY-DEPENDENT SELECTION DURING EXPERIMENTAL COEVOLUTION OF A FRESHWATER SNAIL AND A STERILIZING TREMATODE. Evolution, 63: 2213–2221. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00711.x

- ^ Ford E.B. 1965. Genetic polymorphism, p26, Heterozygous advantage. MIT Press 1965.

- ^ Bertram, Jason; Masel, Joanna (20 March 2019). "Different mechanisms drive the maintenance of polymorphism at loci subject to strong versus weak fluctuating selection". Evolution. 73 (5): 883–896. doi:10.1111/evo.13719. hdl:10150/632441. PMID 30883731. S2CID 83461372.

- ^ Cain A.J. and Currey J.D. Area effects in Cepaea. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 246: 1-81.

- ^ Cain A.J. and Currey J.D. 1968. Climate and selection of banding morphs in Cepaea from the climate optimum to the present day. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 253: 483-98.

- ^ Cain A.J. and Sheppard P.M. 1950. Selection in the polymorphic land snail Cepaea nemoralis (L). Heredity 4:275-94.

- ^ Cain A.J. and Sheppard P.M. 1954. Natural selection in Cepaea. Genetics 39: 89-116.

- ^ Ford E.B. 1975. Ecological genetics, 4th ed. Chapman & Hall, London

- ^ Jones J.S., Leith B.N. & Rawlings P. 1977. Polymorphism in Cepaea: a problem with too many solutions. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 8, 109-143.

- ^ Cook L.M. 1998. A two-stage model for Cepaea polymorphism. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 353, 1577-1593.

- ^ Painter T.S. 1933. "A new method for the study of chromosome rearrangements and the plotting of chromosome maps". Science 78: 585–586.

- ^ Stalker H.D and Carson H.L. 1948. "An altitudinal transect of Drosophila robusta". Evolution 1, 237–48.

- ^ Dobzhansky T. 1970. Genetics of the evolutionary process. Columbia University Press N.Y.

- ^ [Dobzhansky T.] 1981. Dobzhansky's genetics of natural populations. eds Lewontin RC, Moore JA, Provine WB and Wallace B. Columbia University Press N.Y.

- ^ Ford E.B. 1975. Ecological genetics. 4th ed. Chapman & Hall, London.