Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Point mutation

View on Wikipedia

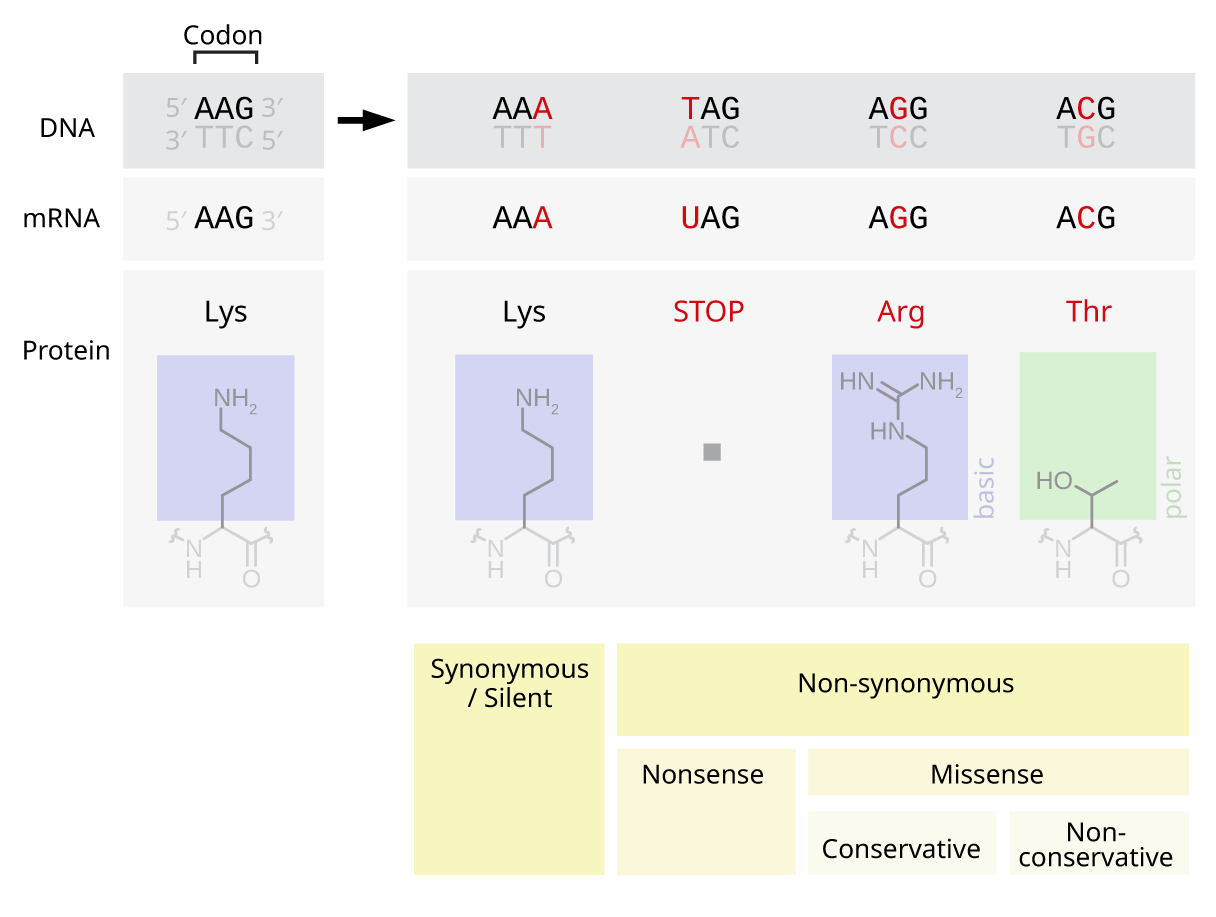

A point mutation is a genetic mutation where a single nucleotide base is changed, inserted or deleted from a DNA or RNA sequence of an organism's genome.[1] Point mutations have a variety of effects on the downstream protein product—consequences that are moderately predictable based upon the specifics of the mutation. These consequences can range from no effect (e.g. synonymous mutations) to deleterious effects (e.g. frameshift mutations), with regard to protein production, composition, and function.

Causes

[edit]Point mutations usually take place during DNA replication. DNA replication occurs when one double-stranded DNA molecule creates two single strands of DNA, each of which is a template for the creation of the complementary strand. A single point mutation can change the whole DNA sequence. Changing one purine or pyrimidine may change the amino acid that the nucleotides code for.

Point mutations may arise from spontaneous mutations that occur during DNA replication. The rate of mutation may be increased by mutagens. Mutagens can be physical, such as radiation from UV rays, X-rays or extreme heat, or chemical (molecules that misplace base pairs or disrupt the helical shape of DNA). Mutagens associated with cancers are often studied to learn about cancer and its prevention.

There are multiple ways for point mutations to occur. First, ultraviolet (UV) light and higher-frequency light have ionizing capability, which in turn can affect DNA. Reactive oxygen molecules with free radicals, which are a byproduct of cellular metabolism, can also be very harmful to DNA. These reactants can lead to both single-stranded and double-stranded DNA breaks. Third, bonds in DNA eventually degrade, which creates another problem to keep the integrity of DNA to a high standard. There can also be replication errors that lead to substitution, insertion, or deletion mutations.

Categorization

[edit]Transition/transversion categorization

[edit]

In 1959 Ernst Freese coined the terms "transitions" or "transversions" to categorize different types of point mutations.[2][3] Transitions are replacement of a purine base with another purine or replacement of a pyrimidine with another pyrimidine. Transversions are replacement of a purine with a pyrimidine or vice versa. There is a systematic difference in mutation rates for transitions (Alpha) and transversions (Beta). Transition mutations are about ten times more common than transversions.

Functional categorization

[edit]Nonsense mutations include stop-gain and start-loss. Stop-gain is a mutation that results in a premature termination codon (a stop was gained), which signals the end of translation. This interruption causes the protein to be abnormally shortened. The number of amino acids lost mediates the impact on the protein's functionality and whether it will function whatsoever.[4] Stop-loss is a mutation in the original termination codon (a stop was lost), resulting in abnormal extension of a protein's carboxyl terminus. Start-gain creates an AUG start codon upstream of the original start site. If the new AUG is near the original start site, in-frame within the processed transcript and downstream to a ribosomal binding site, it can be used to initiate translation. The likely effect is additional amino acids added to the amino terminus of the original protein. Frame-shift mutations are also possible in start-gain mutations, but typically do not affect translation of the original protein. Start-loss is a point mutation in a transcript's AUG start codon, resulting in the reduction or elimination of protein production.

Missense mutations code for a different amino acid. A missense mutation changes a codon so that a different protein is created, a non-synonymous change.[4] Conservative mutations result in an amino acid change. However, the properties of the amino acid remain the same (e.g., hydrophobic, hydrophilic, etc.). At times, a change to one amino acid in the protein is not detrimental to the organism as a whole. Most proteins can withstand one or two point mutations before their function changes. Non-conservative mutations result in an amino acid change that has different properties than the wild type. The protein may lose its function, which can result in a disease in the organism. For example, sickle-cell disease is caused by a single point mutation (a missense mutation) in the beta-hemoglobin gene that converts a GAG codon into GUG, which encodes the amino acid valine rather than glutamic acid. The protein may also exhibit a "gain of function" or become activated, such is the case with the mutation changing a valine to glutamic acid in the BRAF gene; this leads to an activation of the RAF protein which causes unlimited proliferative signalling in cancer cells.[5] These are both examples of a non-conservative (missense) mutation.

Silent mutations code for the same amino acid (a "synonymous substitution"). A silent mutation does not affect the functioning of the protein. A single nucleotide can change, but the new codon specifies the same amino acid, resulting in an unmutated protein. This type of change is called synonymous change since the old and new codon code for the same amino acid. This is possible because 64 codons specify only 20 amino acids. Different codons can lead to differential protein expression levels, however.[4]

Single base pair insertions and deletions

[edit]Sometimes the term point mutation is used to describe insertions or deletions of a single base pair (which has more of an adverse effect on the synthesized protein due to the nucleotides' still being read in triplets, but in different frames: a mutation called a frameshift mutation).[4]

General consequences

[edit]Point mutations that occur in non-coding sequences are most often without consequences, although there are exceptions. If the mutated base pair is in the promoter sequence of a gene, then the expression of the gene may change. Also, if the mutation occurs in the splicing site of an intron, then this may interfere with correct splicing of the transcribed pre-mRNA.

By altering just one amino acid, the entire peptide may change, thereby changing the entire protein. The new protein is called a protein variant. If the original protein functions in cellular reproduction then this single point mutation can change the entire process of cellular reproduction for this organism.

Point germline mutations can lead to beneficial as well as harmful traits or diseases. This leads to adaptations based on the environment where the organism lives. An advantageous mutation can create an advantage for that organism and lead to the trait's being passed down from generation to generation, improving and benefiting the entire population. The scientific theory of evolution is greatly dependent on point mutations in cells. The theory explains the diversity and history of living organisms on Earth. In relation to point mutations, it states that beneficial mutations allow the organism to thrive and reproduce, thereby passing its positively affected mutated genes on to the next generation. On the other hand, harmful mutations cause the organism to die or be less likely to reproduce in a phenomenon known as natural selection.

There are different short-term and long-term effects that can arise from mutations. Smaller ones would be a halting of the cell cycle at numerous points. This means that a codon coding for the amino acid glycine may be changed to a stop codon, causing the proteins that should have been produced to be deformed and unable to complete their intended tasks. Because the mutations can affect the DNA and thus the chromatin, it can prohibit mitosis from occurring due to the lack of a complete chromosome. Problems can also arise during the processes of transcription and replication of DNA. These all prohibit the cell from reproduction and thus lead to the death of the cell. Long-term effects can be a permanent changing of a chromosome, which can lead to a mutation. These mutations can be either beneficial or detrimental. Cancer is an example of how they can be detrimental.[6]

Other effects of point mutations, or single nucleotide polymorphisms in DNA, depend on the location of the mutation within the gene. For example, if the mutation occurs in the region of the gene responsible for coding, the amino acid sequence of the encoded protein may be altered, causing a change in the function, protein localization, stability of the protein or protein complex. Many methods have been proposed to predict the effects of missense mutations on proteins. Machine learning algorithms train their models to distinguish known disease-associated from neutral mutations whereas other methods do not explicitly train their models but almost all methods exploit the evolutionary conservation assuming that changes at conserved positions tend to be more deleterious. While majority of methods provide a binary classification of effects of mutations into damaging and benign, a new level of annotation is needed to offer an explanation of why and how these mutations damage proteins.[7]

Moreover, if the mutation occurs in the region of the gene where transcriptional machinery binds to the protein, the mutation can affect the binding of the transcription factors because the short nucleotide sequences recognized by the transcription factors will be altered. Mutations in this region can affect rate of efficiency of gene transcription, which in turn can alter levels of mRNA and, thus, protein levels in general.

Point mutations can have several effects on the behavior and reproduction of a protein depending on where the mutation occurs in the amino acid sequence of the protein. If the mutation occurs in the region of the gene that is responsible for coding for the protein, the amino acid may be altered. This slight change in the sequence of amino acids can cause a change in the function, activation of the protein meaning how it binds with a given enzyme, where the protein will be located within the cell, or the amount of free energy stored within the protein.

If the mutation occurs in the region of the gene where transcriptional machinery binds to the protein, the mutation can affect the way in which transcription factors bind to the protein. The mechanisms of transcription bind to a protein through recognition of short nucleotide sequences. A mutation in this region may alter these sequences and, thus, change the way the transcription factors bind to the protein. Mutations in this region can affect the efficiency of gene transcription, which controls both the levels of mRNA and overall protein levels.[8]

Specific diseases caused by point mutations

[edit]Point mutations—single‑base changes in the DNA sequence—are one of the most common molecular causes of human disease. By altering a single nucleotide, these mutations can substitute one amino acid for another, introduce premature stop codons, or disrupt normal splicing signals. Depending on where they occur and how they affect the encoded protein, point mutations may abolish enzyme activity, destabilize structural domains, or impair regulatory interactions. In many inherited disorders, a single missense or nonsense substitution is enough to trigger a cascade of biochemical failures, leading to early‐onset or lifelong symptoms. In cancer, somatic point mutations can inactivate tumor suppressors or hyperactivate oncogenes, fueling uncontrolled cell growth.

Across the human genetic landscape, thousands of point‐mutation–driven conditions have been cataloged—from relatively common disorders like sickle‐cell anemia and cystic fibrosis to extremely rare syndromes that affect only a handful of families worldwide. Although each disease has its own pathophysiological details, they share a unifying theme: a precisely localized change in the gene sequence can compromise protein function in a way that no larger chromosomal rearrangement or copy‐number alteration could. Because point mutations are often amenable to targeted genetic testing, they also highlight how molecular diagnosis and personalized therapies (e.g., small molecules that stabilize a mutant enzyme) rely on knowing exactly which codon is altered. Although the following examples illustrate the diversity of point-mutation–mediated disorders, there are over 300,000 such mutations recorded in HGMD and over 1,000,000 variants in ClinVar, reflecting the vast spectrum of human point mutations.[9] [10] [11]

Cancer

[edit]Point mutations in multiple tumor suppressor proteins cause cancer. For instance, point mutations in Adenomatous Polyposis Coli promote tumorigenesis.[12] A novel assay, Fast parallel proteolysis (FASTpp), might help swift screening of specific stability defects in individual cancer patients.[13]

Neurofibromatosis

[edit]Neurofibromatosis is caused by point mutations in the Neurofibromin 1[14][15] or Neurofibromin 2 gene.[16]

Sickle-cell anemia

[edit]Sickle-cell anemia is caused by a point mutation in the β-globin chain of hemoglobin, causing the hydrophilic amino acid glutamic acid to be replaced with the hydrophobic amino acid valine at the sixth position.

The β-globin gene is found on the short arm of chromosome 11. The association of two wild-type α-globin subunits with two mutant β-globin subunits forms hemoglobin S (HbS). Under low-oxygen conditions (being at high altitude, for example), the absence of a polar amino acid at position six of the β-globin chain promotes the non-covalent polymerisation (aggregation) of hemoglobin, which distorts red blood cells into a sickle shape and decreases their elasticity.[17]

Hemoglobin is a protein found in red blood cells, and is responsible for the transportation of oxygen through the body.[18] There are two subunits that make up the hemoglobin protein: beta-globins and alpha-globins.[19] Beta-hemoglobin is created from the genetic information on the HBB, or "hemoglobin, beta" gene found on chromosome 11p15.5.[20] A single point mutation in this polypeptide chain, which is 147 amino acids long, results in the disease known as Sickle Cell Anemia.[21] Sickle-cell anemia is an autosomal recessive disorder that affects 1 in 500 African Americans, and is one of the most common blood disorders in the United States.[20] The single replacement of the sixth amino acid in the beta-globin, glutamic acid, with valine results in deformed red blood cells. These sickle-shaped cells cannot carry nearly as much oxygen as normal red blood cells and they get caught more easily in the capillaries, cutting off blood supply to vital organs. The single nucleotide change in the beta-globin means that even the smallest of exertions on the part of the carrier results in severe pain and even heart attack. Below is a chart depicting the first thirteen amino acids in the normal and abnormal sickle cell polypeptide chain.[21]

| AUG | GUG | CAC | CUG | ACU | CCU | GAG | GAG | AAG | UCU | GCC | GUU | ACU |

| START | Val | His | Leu | Thr | Pro | Glu | Glu | Lys | Ser | Ala | Val | Thr |

| AUG | GUG | CAC | CUG | ACU | CCU | GUG | GAG | AAG | UCU | GCC | GUU | ACU |

| START | Val | His | Leu | Thr | Pro | Val | Glu | Lys | Ser | Ala | Val | Thr |

Tay–Sachs disease

[edit]The cause of Tay–Sachs disease is a genetic defect that is passed from parent to child. This genetic defect is located in the HEXA gene, which is found on chromosome 15.

The HEXA gene makes part of an enzyme called beta-hexosaminidase A, which plays a critical role in the nervous system. This enzyme helps break down a fatty substance called GM2 ganglioside in nerve cells. Mutations in the HEXA gene disrupt the activity of beta-hexosaminidase A, preventing the breakdown of the fatty substances. As a result, the fatty substances accumulate to deadly levels in the brain and spinal cord. The buildup of GM2 ganglioside causes progressive damage to the nerve cells. This is the cause of the signs and symptoms of Tay-Sachs disease.[22]

Repeat-induced point mutation

[edit]In molecular biology, repeat-induced point mutation or RIP is a process by which DNA accumulates G:C to A:T transition mutations. Genomic evidence indicates that RIP occurs or has occurred in a variety of fungi[23] while experimental evidence indicates that RIP is active in Neurospora crassa,[24] Podospora anserina,[25] Magnaporthe grisea,[26] Leptosphaeria maculans,[27] Gibberella zeae,[28] Nectria haematococca[29] and Paecilomyces variotii.[30] In Neurospora crassa, sequences mutated by RIP are often methylated de novo.[24]

RIP occurs during the sexual stage in haploid nuclei after fertilization but prior to meiotic DNA replication.[24] In Neurospora crassa, repeat sequences of at least 400 base pairs in length are vulnerable to RIP. Repeats with as low as 80% nucleotide identity may also be subject to RIP. Though the exact mechanism of repeat recognition and mutagenesis are poorly understood, RIP results in repeated sequences undergoing multiple transition mutations.

The RIP mutations do not seem to be limited to repeated sequences. Indeed, for example, in the phytopathogenic fungus L. maculans, RIP mutations are found in single copy regions, adjacent to the repeated elements. These regions are either non-coding regions or genes encoding small secreted proteins including avirulence genes. The degree of RIP within these single copy regions was proportional to their proximity to repetitive elements.[31]

Rep and Kistler have speculated that the presence of highly repetitive regions containing transposons, may promote mutation of resident effector genes.[32] So the presence of effector genes within such regions is suggested to promote their adaptation and diversification when exposed to strong selection pressure.[33]

As RIP mutation is traditionally observed to be restricted to repetitive regions and not single copy regions, Fudal et al.[34] suggested that leakage of RIP mutation might occur within a relatively short distance of a RIP-affected repeat. Indeed, this has been reported in N. crassa whereby leakage of RIP was detected in single copy sequences at least 930 bp from the boundary of neighbouring duplicated sequences.[35] To elucidate the mechanism of detection of repeated sequences leading to RIP may allow to understand how the flanking sequences may also be affected.

Mechanism

[edit]RIP causes G:C to A:T transition mutations within repeats, however, the mechanism that detects the repeated sequences is unknown. RID is the only known protein essential for RIP. It is a DNA methyltransferease-like protein, that when mutated or knocked out results in loss of RIP.[36] Deletion of the rid homolog in Aspergillus nidulans, dmtA, results in loss of fertility[37] while deletion of the rid homolog in Ascobolus immersens, masc1, results in fertility defects and loss of methylation induced premeiotically (MIP).[38]

Consequences

[edit]RIP is believed to have evolved as a defense mechanism against transposable elements, which resemble parasites by invading and multiplying within the genome. RIP creates multiple missense and nonsense mutations in the coding sequence. This hypermutation of G-C to A-T in repetitive sequences eliminates functional gene products of the sequence (if there were any to begin with). In addition, many of the C-bearing nucleotides become methylated, thus decreasing transcription.

Use in molecular biology

[edit]Because RIP is so efficient at detecting and mutating repeats, biologists working on Neurospora crassa have used it as a tool for mutagenesis. A second copy of a single-copy gene is first transformed into the genome. The fungus must then mate and go through its sexual cycle to activate the RIP machinery. Many different mutations within the duplicated gene are obtained from even a single fertilization event so that inactivated alleles, usually due to nonsense mutations, as well as alleles containing missense mutations can be obtained.[39]

History

[edit]This section needs expansion with: more information about the history of research specifically on point mutations rather than cell division in general. You can help by adding to it. (January 2025) |

The cellular reproduction process of meiosis was discovered by Oscar Hertwig in 1876. Mitosis was discovered several years later in 1882 by Walther Flemming.

Hertwig studied sea urchins, and noticed that each egg contained one nucleus prior to fertilization and two nuclei after. This discovery proved that one spermatozoon could fertilize an egg, and therefore proved the process of meiosis. Hermann Fol continued Hertwig's research by testing the effects of injecting several spermatozoa into an egg, and found that the process did not work with more than one spermatozoon.[40]

Flemming began his research of cell division starting in 1868. The study of cells was an increasingly popular topic in this time period. By 1873, Schneider had already begun to describe the steps of cell division. Flemming furthered this description in 1874 and 1875 as he explained the steps in more detail. He also argued with Schneider's findings that the nucleus separated into rod-like structures by suggesting that the nucleus actually separated into threads that in turn separated. Flemming concluded that cells replicate through cell division, to be more specific mitosis.[41]

Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl are credited with the discovery of DNA replication. Watson and Crick acknowledged that the structure of DNA did indicate that there is some form of replicating process. However, there was not a lot of research done on this aspect of DNA until after Watson and Crick. People considered all possible methods of determining the replication process of DNA, but none were successful until Meselson and Stahl. Meselson and Stahl introduced a heavy isotope into some DNA and traced its distribution. Through this experiment, Meselson and Stahl were able to prove that DNA reproduces semi-conservatively.[42]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Point Mutation". Biology Dictionary. 22 November 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Freese, Ernst (April 1959). "The difference between spontaneous and base-analogue induced mutations of phage T4". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 45 (4): 622–33. Bibcode:1959PNAS...45..622F. doi:10.1073/pnas.45.4.622. PMC 222607. PMID 16590424.

- ^ Freese, Ernst (1959). "The Specific Mutagenic Effect of Base Analogues on Phage T4". J. Mol. Biol. 1 (2): 87–105. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(59)80038-3.

- ^ a b c d "Genetics Primer". Archived from the original on 11 April 2005.

- ^ Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. (June 2002). "Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer" (PDF). Nature. 417 (6892): 949–54. Bibcode:2002Natur.417..949D. doi:10.1038/nature00766. PMID 12068308. S2CID 3071547.

- ^ Hoeijmakers JH (May 2001). "Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer". Nature. 411 (6835): 366–74. Bibcode:2001Natur.411..366H. doi:10.1038/35077232. PMID 11357144. S2CID 4337913.

- ^ Li, Minghui; Goncearenco, Alexander; Panchenko, Anna R. (2017). "Annotating Mutational Effects on Proteins and Protein Interactions: Designing Novel and Revisiting Existing Protocols". Proteomics. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1550. pp. 235–260. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-6747-6_17. ISBN 978-1-4939-6745-2. ISSN 1940-6029. PMC 5388446. PMID 28188534.

- ^ "A Shortcut to Personalized Medicine". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. 18 June 2008.

- ^ Stenson, Peter D.; Mort, Michael; Ball, Edward V.; Shaw, Kristen; Phillips, Andrew D.; Cooper, David N. (2014). "The Human Gene Mutation Database: building a comprehensive mutation repository for clinical and molecular genetics, diagnostic testing and personalized genomic medicine". Human Genetics. 133 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s00439-013-1358-4. PMC 3898141. PMID 24077912.

- ^ Landrum, Michael J.; Lee, James M.; Riley, G. R.; Jang, Whi; Rubinstein, W. S.; Church, Donna M.; Maglott, Donna R. (2014). "ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (Database issue): D980 – D985. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1113. PMC 3965032. PMID 24234437.

- ^ Karczewski, Konrad J.; Francioli, Laurent C.; Tiao, Grace; Cummings, Beryl B.; Alföldi, Jessica; Wang, Qingbo (2020). "The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans". Nature. 581 (7809): 434–443. Bibcode:2020Natur.581..434K. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. hdl:10044/1/79060. PMC 7334197. PMID 32461654.

- ^ Minde DP, Anvarian Z, Rüdiger SG, Maurice MM (2011). "Messing up disorder: how do missense mutations in the tumor suppressor protein APC lead to cancer?". Mol. Cancer. 10 101. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-10-101. PMC 3170638. PMID 21859464.

- ^ Minde DP, Maurice MM, Rüdiger SG (2012). "Determining biophysical protein stability in lysates by a fast proteolysis assay, FASTpp". PLOS ONE. 7 (10) e46147. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...746147M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046147. PMC 3463568. PMID 23056252.

- ^ Serra, E; Ars, E; Ravella, A; Sánchez, A; Puig, S; Rosenbaum, T; Estivill, X; Lázaro, C (2001). "Somatic NF1 mutational spectrum in benign neurofibromas: MRNA splice defects are common among point mutations". Human Genetics. 108 (5): 416–29. doi:10.1007/s004390100514. PMID 11409870. S2CID 2136834.

- ^ Wiest, V; Eisenbarth, I; Schmegner, C; Krone, W; Assum, G (2003). "Somatic NF1 mutation spectra in a family with neurofibromatosis type 1: Toward a theory of genetic modifiers". Human Mutation. 22 (6): 423–7. doi:10.1002/humu.10272. PMID 14635100. S2CID 22140210.

- ^ Mohyuddin, A; Neary, W. J.; Wallace, A; Wu, C. L.; Purcell, S; Reid, H; Ramsden, R. T.; Read, A; Black, G; Evans, D. G. (2002). "Molecular genetic analysis of the NF2 gene in young patients with unilateral vestibular schwannomas". Journal of Medical Genetics. 39 (5): 315–22. doi:10.1136/jmg.39.5.315. PMC 1735110. PMID 12011146.

- ^ Genes and Disease. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). 29 September 1998 – via PubMed.

- ^ Hsia CC (January 1998). "Respiratory function of hemoglobin". N. Engl. J. Med. 338 (4): 239–47. doi:10.1056/NEJM199801223380407. PMID 9435331.

- ^ "HBB — Hemoglobin, Beta". Genetics Home Reference. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b "Anemia, Sickle Cell". Genes and Disease. Bethesda MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information. 1998. NBK22183.

- ^ a b Clancy S (2008). "Genetic Mutation". Nature Education. 1 (1): 187.

- ^ eMedTV. "Causes of Tay-Sachs". Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ Clutterbuck AJ (2011). "Genomic evidence of repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) in filamentous ascomycetes". Fungal Genet Biol. 48 (3): 306–26. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2010.09.002. PMID 20854921.

- ^ a b c Selker EU, Cambareri EB, Jensen BC, Haack KR (December 1987). "Rearrangement of duplicated DNA in specialized cells of Neurospora". Cell. 51 (5): 741–752. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90097-3. PMID 2960455. S2CID 23036409.

- ^ Graïa F, Lespinet O, Rimbault B, Dequard-Chablat M, Coppin E, Picard M (May 2001). "Genome quality control: RIP (repeat-induced point mutation) comes to Podospora". Mol Microbiol. 40 (3): 586–595. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02367.x. PMID 11359565. S2CID 25096512.

- ^ Ikeda K, Nakayashiki H, Kataoka T, Tamba H, Hashimoto Y, Tosa Y, Mayama S (September 2002). "Repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) in Magnaporthe grisea: implications for its sexual cycle in the natural field context". Mol Microbiol. 45 (5): 1355–1364. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03101.x. PMID 12207702.

- ^ Idnurm A, Howlett BJ (June 2003). "Analysis of loss of pathogenicity mutants reveals that repeat-induced point mutations can occur in the Dothideomycete Leptosphaeria maculans". Fungal Genet Biol. 39 (1): 31–37. doi:10.1016/S1087-1845(02)00588-1. PMID 12742061.

- ^ Cuomo CA, Güldener U, Xu JR, Trail F, Turgeon BG, Di Pietro A, Walton JD, Ma LJ, et al. (September 2007). "The Fusarium graminearum genome reveals a link between localized polymorphism and pathogen specialization". Science. 317 (5843): 1400–2. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1400C. doi:10.1126/science.1143708. PMID 17823352. S2CID 11080216.

- ^ Coleman JJ, Rounsley SD, Rodriguez-Carres M, Kuo A, Wasmann CC, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, et al. (August 2009). "The genome of Nectria haematococca: contribution of supernumerary chromosomes to gene expansion". PLOS Genet. 5 (8) e1000618. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000618. PMC 2725324. PMID 19714214.

- ^ Urquhart, Andrew S.; Mondo, Stephen J.; Mäkelä, Miia R.; Hane, James K.; Wiebenga, Ad; He, Guifen; Mihaltcheva, Sirma; Pangilinan, Jasmyn; Lipzen, Anna; Barry, Kerrie; de Vries, Ronald P.; Grigoriev, Igor V.; Idnurm, Alexander (13 December 2018). "Genomic and Genetic Insights Into a Cosmopolitan Fungus, Paecilomyces variotii (Eurotiales)". Frontiers in Microbiology. 9 3058. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.03058. hdl:20.500.11937/74553. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 6300479. PMID 30619145.

- ^ Van de Wouw AP, Cozijnsen AJ, Hane JK, et al. (2010). "Evolution of linked avirulence effectors in Leptosphaeria maculans is affected by genomic environment and exposure to resistance genes in host plants". PLOS Pathog. 6 (11) e1001180. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001180. PMC 2973834. PMID 21079787.

- ^ Rep M, Kistler HC (August 2010). "The genomic organization of plant pathogenicity in Fusarium species". Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13 (4): 420–6. Bibcode:2010COPB...13..420R. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.004. PMID 20471307. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ Farman ML (August 2007). "Telomeres in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae: the world of the end as we know it". FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 273 (2): 125–32. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00812.x. PMID 17610516.

- ^ Fudal I, Ross S, Brun H, et al. (August 2009). "Repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) as an alternative mechanism of evolution toward virulence in Leptosphaeria maculans". Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22 (8): 932–41. Bibcode:2009MPMI...22..932F. doi:10.1094/MPMI-22-8-0932. PMID 19589069.

- ^ Irelan JT, Hagemann AT, Selker EU (December 1994). "High frequency repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) is not associated with efficient recombination in Neurospora". Genetics. 138 (4): 1093–103. doi:10.1093/genetics/138.4.1093. PMC 1206250. PMID 7896093.

- ^ Freitag M, Williams RL, Kothe GO, Selker EU (2002). "A cytosine methyltransferase homologue is essential for repeat-induced point mutation in Neurospora crassa". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99 (13): 8802–7. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.8802F. doi:10.1073/pnas.132212899. PMC 124379. PMID 12072568.

- ^ Lee DW, Freitag M, Selker EU, Aramayo R (2008). "A cytosine methyltransferase homologue is essential for sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans". PLOS ONE. 3 (6) e2531. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2531L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002531. PMC 2432034. PMID 18575630.

- ^ Malagnac F, Wendel B, Goyon C, Faugeron G, Zickler D, Rossignol JL, et al. (1997). "A gene essential for de novo methylation and development in Ascobolus reveals a novel type of eukaryotic DNA methyltransferase structure". Cell. 91 (2): 281–90. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80410-9. PMID 9346245. S2CID 14143830.

- ^ Selker EU (1990). "Premeiotic instability of repeated sequences in Neurospora crassa". Annu Rev Genet. 24: 579–613. doi:10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.003051. PMID 2150906.

- ^ Barbieri, Marcello (2003). "The problem of generation". The organic codes: an introduction to semantic biology. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-521-53100-9.

- ^ Paweletz N (January 2001). "Walther Flemming: pioneer of mitosis research". Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2 (1): 72–5. doi:10.1038/35048077. PMID 11413469. S2CID 205011982.

- ^ Holmes, Frederic Lawrence (2001). Meselson, Stahl, and the replication of DNA: a history of "the most beautiful experiment in biology". Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08540-2.

External links

[edit]- Point+Mutation at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Point mutation

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Scope

A point mutation is a type of genetic mutation involving an alteration at a single position in the DNA sequence, most commonly a substitution where one nucleotide base is replaced by another.[4] This change affects only one base pair in the double-stranded DNA molecule, which consists of four nucleotide bases: adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). These bases pair specifically—A with T via two hydrogen bonds, and C with G via three hydrogen bonds—forming the rungs of the DNA double helix.[5] While substitutions represent the typical form, the term point mutation sometimes encompasses small insertions or deletions of a single base pair, though these can shift the reading frame during protein translation.[6] Point mutations are distinguished from larger-scale genetic alterations, such as chromosomal aberrations (e.g., deletions or duplications of extensive DNA segments) or insertions/deletions (indels) spanning multiple base pairs, which impact broader genomic regions and often lead to more severe structural changes.[7] In contrast, point mutations are localized to one site and may result in various outcomes depending on their location and nature, including silent mutations (no amino acid change), missense mutations (altered amino acid), nonsense mutations (premature stop codon), or frameshift mutations (from single-base indels).[8] These effects arise from errors in DNA replication or damage but are confined without disrupting the overall chromosomal architecture.[2] The scope of point mutations extends across all genomic contexts and organisms, occurring in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes where they serve as a primary source of genetic variation.[2] In eukaryotic genomes, which include both coding (exons) and non-coding regions (introns, regulatory elements, and intergenic spaces), point mutations can influence protein-coding sequences or modulate gene expression if they affect non-coding functional elements.[9] Similarly, prokaryotic genomes, lacking extensive introns, experience point mutations primarily in their compact coding and regulatory regions, contributing to adaptive evolution in bacteria.[10] Overall, these mutations are fundamental to genetic diversity, with their prevalence shaped by repair mechanisms and selective pressures in both unicellular and multicellular life forms.[2]Molecular Context

Point mutations occur within the context of DNA's double-helical structure, where two antiparallel strands are stabilized by hydrogen bonds between complementary base pairs: adenine (A) with thymine (T) via two hydrogen bonds, and guanine (G) with cytosine (C) via three hydrogen bonds.[11] This specific base pairing ensures the structural integrity and functional fidelity of the genome, as the double helix allows for accurate unwinding and separation during cellular processes. A point mutation, involving the substitution of a single nucleotide, disrupts this pairing by introducing a mismatch, such as replacing an A with a G, which can lead to instability in the helix or errors in subsequent molecular interactions.[12] During DNA replication, point mutations primarily arise from errors introduced by DNA polymerase enzymes, which synthesize new strands by adding nucleotides complementary to the template. In eukaryotes, replicative polymerases such as DNA polymerase δ and ε incorporate nucleotides with high selectivity, but intrinsic errors occur approximately once every 10^4 to 10^5 bases before proofreading. The overall replication fidelity is enhanced by the polymerase's 3'→5' exonuclease proofreading activity and post-replicative mismatch repair, achieving an error rate of approximately 10^{-9} to 10^{-10} mutations per base pair per cell division.[13][14] In the transcription process, point mutations within protein-coding genes alter the DNA template, leading to corresponding changes in the synthesized messenger RNA (mRNA) sequence, which can affect splicing, stability, or translation into proteins. These genomic mutations are distinct from RNA editing events, which involve post-transcriptional modifications to the mRNA itself, such as base conversions by enzymes like ADAR, without altering the underlying DNA.[15][16] Point mutations can occur at various chromosomal locations within genes, including exons (coding regions that are retained in mature mRNA) and introns (non-coding intervening sequences removed during splicing), as well as in regulatory regions such as promoters upstream of the transcription start site. Mutations in exons directly impact the protein-coding sequence, while those in introns may disrupt splice sites, and alterations in promoters can impair transcription initiation by affecting RNA polymerase binding or regulatory factor recruitment.[17][18]Causes

Spontaneous Causes

Spontaneous point mutations arise from intrinsic biochemical processes within the cell, independent of external agents, and represent a fundamental source of genetic variation. These mutations occur at low but measurable rates during DNA maintenance and replication, primarily due to the chemical instability of DNA bases and the inherent limitations of enzymatic fidelity. Although most such errors are corrected by cellular repair mechanisms, those that persist can lead to base substitutions or small insertions/deletions. Key processes include hydrolytic reactions, tautomeric shifts, polymerase inaccuracies, and oxidative damage from metabolic byproducts. Depurination involves the spontaneous hydrolysis of the N-glycosidic bond linking a purine base (adenine or guanine) to the deoxyribose sugar in the DNA backbone, resulting in an apurinic (AP) site. This occurs at a rate of approximately 10,000 to 20,000 events per mammalian cell per day under physiological conditions, primarily driven by water molecules acting as nucleophiles. During subsequent DNA replication, the AP site can cause transversion mutations if the polymerase inserts an adenine opposite the vacancy, leading to a purine-to-pyrimidine substitution in the daughter strand. The chemical reaction can be represented as: Deamination, another hydrolytic process, entails the removal of an amino group from a base, most commonly cytosine, converting it to uracil. This reaction proceeds via nucleophilic attack by water on the C4 amino group, yielding uracil and ammonia at a rate of about 100 to 500 cytosine residues per human cell per day. If unrepaired, uracil pairs with adenine during replication, resulting in a C-to-T transition mutation. The process is depicted as: Less frequent deaminations affect adenine (to hypoxanthine, pairing with cytosine) and guanine (to xanthine, which still pairs with cytosine but may stall replication), but cytosine deamination predominates due to its higher susceptibility. Tautomerization refers to the reversible isomerization of DNA bases between their common keto or amino forms and rare enol or imino forms, facilitated by proton shifts under physiological conditions. This transient shift alters hydrogen-bonding patterns, promoting non-standard base pairing during DNA replication. For instance, the enol tautomer of thymine can form two hydrogen bonds with guanine instead of adenine, potentially causing a T-to-C transition if the error persists. Such events are rare, occurring at frequencies around 10^{-4} to 10^{-5} per base pair, but contribute to spontaneous mutagenesis without external triggers. Replication errors stem from the intrinsic infidelity of DNA polymerases, which occasionally insert incorrect nucleotides due to base slippage or wobble pairing, particularly in repetitive sequences. High-fidelity polymerases like DNA polymerase δ and ε exhibit base insertion error rates of about 10^{-5} to 10^{-7} per nucleotide, exacerbated by slippage in microsatellites where the nascent strand temporarily dissociates and realigns, leading to small indels. Proofreading by the polymerase's 3'→5' exonuclease activity enhances fidelity by 100- to 1,000-fold, excising mismatched bases, yet deficiencies or overwhelming error loads allow some mismatches to evade correction, contributing to point mutations at an overall rate of approximately 10^{-9} to 10^{-10} per base pair in vivo. Endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS), generated as byproducts of cellular metabolism such as mitochondrial respiration, induce oxidative lesions in DNA that manifest as point mutations. Superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals attack guanine preferentially, forming 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG), one of the most abundant oxidative adducts, at rates estimated at 100 to 1,000 lesions per human cell per day. During replication, 8-oxoG mispairs with adenine, yielding G-to-T transversions if not repaired by base excision repair pathways. This process underscores how normal metabolic activity inadvertently promotes genomic instability.Induced Causes

Induced point mutations arise from exposure to external agents that chemically or physically alter DNA bases, leading to errors during replication or repair. These mutagens include chemicals and radiation, which can be encountered environmentally or applied deliberately in laboratory settings. Unlike spontaneous mutations from endogenous processes, induced ones often result from deliberate chemical modifications or energy deposition that targets specific DNA components.[2] Chemical mutagens are among the most studied inducers of point mutations, primarily through alkylation or base mimicry. Alkylating agents, such as ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS), react with guanine bases to form O6-alkylguanine adducts, which mispair with thymine during replication, predominantly causing G-to-A transitions.[2] EMS is highly effective due to its ability to alkylate DNA at multiple sites, resulting in a high mutation rate of up to 10^{-3} per locus in treated organisms.[19] Another class, base analogs like 5-bromouracil (5-BU), incorporates into DNA in place of thymine but exists in a tautomeric form that pairs with guanine, leading to A-T to G-C transitions.[2] The mutagenic potential of 5-BU stems from its shifted enol-keto equilibrium, increasing mispairing frequency compared to natural bases.[2] Radiation exposure also induces point mutations by damaging DNA bases or generating reactive species. Ultraviolet (UV) light, particularly UVB wavelengths, forms cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) between adjacent thymine or cytosine bases, which, if unrepaired or processed via error-prone translesion synthesis, result in C-to-T or CC-to-TT substitutions—commonly known as UV signature mutations.[20] Ionizing radiation, such as X-rays or gamma rays, produces reactive oxygen species that cause oxidative base modifications, including 8-oxoguanine, which mispairs with adenine to yield G-to-T transversions, alongside direct strand breaks that can lead to base substitutions during repair.[21] These effects are dose-dependent, with mutation frequencies increasing linearly with exposure levels across cell types.[22] In experimental contexts, induced point mutations are harnessed for genetic studies using model organisms. EMS mutagenesis, for instance, is widely applied in forward and reverse genetics screens in species like Arabidopsis thaliana, Caenorhabditis elegans, and rice, where soaked seeds or larvae are treated to generate libraries of mutants with random point mutations for phenotypic analysis.[23] This approach has facilitated the identification of thousands of genes involved in development and stress responses, with mutation rates tailored by EMS concentration (typically 0.1-1% solutions).[24] Such techniques enable high-throughput sequencing to map induced variants, contrasting with natural mutation rates by orders of magnitude.[19] Environmental exposures contribute to induced point mutations through chronic low-level contact with mutagens. Cigarette smoke contains polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and nitrosamines that act as alkylating agents, inducing G-to-T transversions in genes like TP53 and KRAS, which are hallmarks of smoking-related lung cancers.[25] Similarly, industrial pollutants such as benzene derivatives function as alkylators, elevating point mutation rates in exposed populations via base alkylation akin to EMS.[26] These agents often bypass standard repair mechanisms, amplifying mutation accumulation over time.[27]Classification

Substitution Types

Point mutations involving substitutions replace one nucleotide base with another without altering the DNA sequence length. These substitutions are categorized into two main types based on the chemical properties of the bases involved: transitions and transversions.[28] Transitions occur when a purine base is substituted for another purine (adenine [A] to guanine [G] or vice versa) or a pyrimidine base for another pyrimidine (cytosine [C] to thymine [T] or vice versa).[28] These changes involve bases with similar chemical structures and shapes, which facilitates tautomeric shifts during replication and contributes to their higher occurrence compared to other substitutions.[28] A common example is the C-to-T transition resulting from the spontaneous deamination of cytosine to uracil, which is often not repaired and leads to a mismatch during replication.[29] Another frequent transition is G-to-A, particularly at hotspots in CpG dinucleotides where cytosine methylation increases deamination rates, effectively yielding this substitution on the complementary strand.[30] Transversions, in contrast, involve the substitution of a purine for a pyrimidine or vice versa, such as A-to-C, A-to-T, G-to-C, or G-to-T.[28] These exchanges occur between bases with dissimilar shapes and chemical properties, making them less likely during normal replication errors and often associated with more severe DNA damage from external agents.[28] In many genomes, including the human genome, transitions outnumber transversions, with a typical ratio of approximately 2:1.[31] This bias arises from both mutational processes and selective pressures, influencing the overall pattern of molecular evolution by favoring certain synonymous changes in coding regions.[32]Functional Classifications

Point mutations are functionally classified based on their effects on gene expression and protein function, primarily arising from substitutions in coding or regulatory regions.[12] This classification includes silent, missense, and nonsense mutations within exons, which influence the protein sequence through changes in codons, as well as regulatory mutations that alter non-coding elements like promoters and splice sites.[33] These categories highlight how a single nucleotide change can range from neutral to severely disruptive, depending on the genetic code's degeneracy and the mutation's location.[34] Silent mutations occur when a nucleotide substitution changes a codon but does not alter the encoded amino acid, due to the degeneracy of the genetic code where multiple codons specify the same amino acid.[12] For example, changing CGU to CGC both code for arginine, resulting in no change to the protein sequence.[12] Such mutations are typically neutral in terms of protein function, though they may subtly affect translation efficiency in some contexts.[35] Missense mutations involve a nucleotide change that results in a codon specifying a different amino acid, leading to a single amino acid substitution in the protein.[12] An illustrative case is the substitution of CGU (arginine) to CAU (histidine), which alters the protein's chemical properties.[12] A well-known example is the GAG to GTG change in the beta-globin gene, replacing glutamic acid with valine and causing sickle cell anemia.[36] Nonsense mutations convert a codon for an amino acid into a premature stop codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA), truncating the protein and often rendering it nonfunctional.[12] For instance, CAG (glutamine) to TAG (stop) at codon 161 in the low-density lipoprotein receptor gene leads to a shortened protein.[37] The impact depends on the position, with early stops causing more severe loss of function.[38] Regulatory mutations affect non-coding regions, such as promoters that influence transcription initiation or splice sites that direct pre-mRNA processing, thereby altering gene expression levels or mRNA isoform production without changing the protein sequence.[39] Examples include mutations in splice donor sites, like c.1845+1G>A in the NF1 gene, which disrupts exon recognition and causes exon skipping in neurofibromatosis type 1.[39] Promoter variants can similarly reduce transcription rates by impairing transcription factor binding.[40] To illustrate how substitutions map to these functional classes, consider the following examples from the standard genetic code, which exhibits degeneracy primarily at the third codon position:| Original Codon | Mutation | New Codon | Amino Acid Change | Functional Class | Example Amino Acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGU | U to C | CGC | None | Silent | Arginine to Arginine [12] |

| CGU | G to A | CAU | Arg to His | Missense | Arginine to Histidine [12] |

| CAG | C to T | TAG | Gln to Stop | Nonsense | Glutamine to Stop [37] |

| GAG (beta-globin) | A to T | GTG | Glu to Val | Missense | Glutamic acid to Valine [36] |