Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

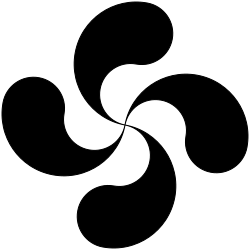

Lauburu

View on Wikipedia

The lauburu (from Basque lau, "four" + buru, "head") is an ancient swastika with four comma-shaped heads and the most widely known traditional symbol of the Basque Country and the Basque people.[1] In the past, it has also been associated with the Galicians, Illyrians and Asturians.[citation needed]

A variant of lauburu consisting of geometrically curved lines can be constructed with a compass and straightedge, beginning with the formation of a square template; each head can be drawn from a neighboring vertex of this template with two compass settings, with one radius half the length of the other.

Background

[edit]Historians and authorities have attempted to apply allegorical meaning to the ancient symbol of lauburu. Augustin Chaho[2] said it signifies the "four heads or regions" of the Basque Country. The lauburu does not appear in any of the seven historical provinces' coats-of-arms that have been combined in the arms of the Basque Country: Biscay, Gipuzkoa, Araba, Upper Navarre, Lower Navarre, Labourd, and Soule. While some authors have suggested that the four heads of lauburu could signify, e.g., form, life, sensibility, and conscience,[3] lauburu is more generally considered just a symbol of prosperity and good fortune.

After the time of the Antonines, Camille Jullian[4] finds no specimen of swastikas, round or straight, in the Basque areas until modern times.

Louis Colas[5] considers that the lauburu is not related to the swastika but comes from Paracelsus and marks the tombs of healers of animals and healers of souls (i.e., priests). Around the end of the 16th century, the lauburu appears abundantly as a Basque decorative element, in wooden chests or tombs, perhaps as another form of the cross.[6] Straight swastikas are not found until the 19th century.

Many Basque homes and shops display the symbol over the doorway as a sort of talisman. Sabino Arana interpreted it as a solar symbol, to support his own theory of a hypothetical Basque solar cult (based on etymologies that have later been shown to be incorrect) in the first issue of the daily newspaper Euzkadi in 1913.

The lauburu has been featured on flags and emblems of various Basque political organisations including Eusko Abertzale Ekintza (EAE-ANV).

The use of the lauburu as a cultural icon fell into some disuse during the Francoist regime in Spain (1939–1975), which repressed many elements of Basque culture.

Etymology

[edit]Lau buru means "four heads", "four ends" or "four summits" in modern Basque. In some sources it has been argued that this might be a folk etymology applied to the Latin labarum.[7]

However, Father Fidel Fita thought the relation reversed, labarum being adapted from Basque, under Augustus Caesar's rule.[8]

Gallery

[edit]-

Flag of Arrieta.

-

A lauburu carved into a stone.

-

The lyre of Joaquina Téllez-Girón, Marchioness of Santa Cruz by Francisco de Goya (around 1805) is decorated with a lauburu.

-

A lauburu on the baptismal font at the church of Knopp-Labach

-

EAE-ANV logo

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Barrentsoro, Karlox Iturria (1 July 1989). "Lauburua, bizi-indarraren gurpila" [Lauburua, the wheel of life force]. zientzia.eus (in Basque). Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Chaho, Augustin (1847). Histoire Primitive des Euskariens-Basques [Primitive History of the Euskadi-Basques] (in French). Bayonne: Bonzom. p. 31.. Quoted by Santiago de Pablo, pages 114 and 115.

- ^ "The Lauburu and Its Symbolism: "Imanol Mujica, presentation at a conference about the lauburu's symbolism on May 25, 1968 in Bogota, Colombia."". Archived from the original on 2002-06-18.

- ^ Camille Jullian in his preface to La tombe basque, according to Lauburu: La swástika rectilínea en el País Vasco (Auñamendi Entziklopedia).

- ^ Louis COLAS, La Tombe Basque, Biarritz, Grande Imprimerie Moderne, 1923, pp. 37-9. Mentioned in Pablo, Santiago de (2009). "El lauburu. Política, cultura e identidad nacional en torno a un símbolo del País Vasco" [The lauburu. Politics, culture and national identity around a symbol of the Basque Country] (PDF). Memoria y Civilización (in Spanish) (12). Pamplona: Universidad de Navarra: 109–153. ISSN 1139-0107.

- ^ Lauburu: Conclusiones in Auñamendi Entziklopedia.

- ^ "Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia". Euskaltzaindia. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ Letter from Fita to Fernández Guerra, reproduced in his Cantabria, note 8, page 126, reproduced in Historia crítica de Vizcaya y de sus Fueros, by Gregorio Balparda, according to Auñamendi Entziklopedia

External links

[edit]- "La croix Basque, lauburu": demonstrating the layout for scribing the arms.