Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Basque language

View on WikipediaThis article has an unclear citation style. (September 2025) |

| Basque | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| euskara | ||||

| Pronunciation | IPA: [eus̺ˈkaɾa] | |||

| Native to | France, Spain | |||

| Region | Basque Country | |||

| Ethnicity | Basque | |||

Native speakers | 806,000 (2021)[1] 434,000 passive speakers[2] | |||

Early forms | ||||

| Dialects | ||||

| Official status | ||||

Official language in | Spain | |||

| Regulated by | Euskaltzaindia | |||

| Language codes | ||||

| ISO 639-1 | eu | |||

| ISO 639-2 | baq (B) eus (T) | |||

| ISO 639-3 | eus | |||

| Glottolog | basq1248 | |||

| Linguasphere | 40-AAA-a | |||

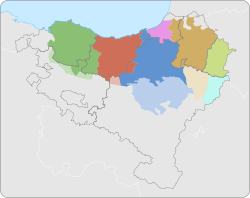

Dialect areas of Basque. Light-coloured dialects are extinct. See § Dialects | ||||

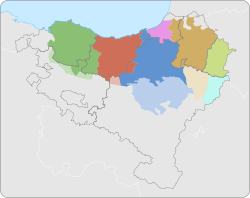

Basque speakers, including second-language speakers[3]

| ||||

| Person | Basque (Euskaldun) |

|---|---|

| People | Basques (Euskaldunak) |

| Language | Basque (Euskara) |

| Culture of Basque Country |

|---|

|

| Mythology |

| Literature |

Basque (/ˈbæsk, ˈbɑːsk/ BASK, BAHSK;[4] euskara [eus̺ˈkaɾa]) is a language spoken by Basques and other residents of the Basque Country, a region that straddles the westernmost Pyrenees in adjacent parts of southwestern France and northern Spain. Basque is classified as a language isolate (unrelated to any other known languages), the only one in Europe. The Basques are indigenous to and primarily inhabit the Basque Country.[5] The Basque language is spoken by 806,000 Basques in all territories. Of them, 93.7% (756,000) are in the Spanish area of the Basque Country and the remaining 6.3% (51,000) are in the French portion.[1]

Native speakers live in a contiguous area that includes parts of four Spanish provinces and the three "ancient provinces" in France. Gipuzkoa, most of Biscay, a few municipalities on the northern border of Álava and the northern area of Navarre formed the core of the remaining Basque-speaking area before measures were introduced in the 1980s to strengthen Basque fluency. By contrast, most of Álava, the westernmost part of Biscay, and central and southern Navarre are predominantly populated by native speakers of Spanish, either because Basque was replaced by either Navarro-Aragonese or Spanish over the centuries (as in most of Álava and central Navarre), or because it may never have been spoken there (as in parts of Enkarterri and south-eastern Navarre).

In Francoist Spain, Basque language use was discouraged by the government's repressive policies. In the Basque Country, "Francoist repression was not only political, but also linguistic and cultural."[6] Franco's regime suppressed Basque from official discourse, education, and publishing,[7] making it illegal to register newborn babies under Basque names,[8] and even requiring tombstone engravings in Basque to be removed.[9] In some provinces the public use of Basque was suppressed, with people fined for speaking it.[10] Public use of Basque was frowned upon by supporters of the regime, often regarded as a sign of anti-Francoism or separatism.[11] In the 1960s and later, the trend reversed and education and publishing in Basque began to flourish.[12] As a part of this process, a standardised form of the Basque language, called Euskara Batua, was developed by the Euskaltzaindia in the late 1960s.

Besides its standardised version, the five historic Basque dialects are Biscayan, Gipuzkoan, and Upper Navarrese in Spain and Navarrese–Lapurdian and Souletin in France. They take their names from the historic Basque provinces, but the dialect boundaries are not congruent with province boundaries. Euskara Batua was created so that the Basque language could be used—and easily understood by all Basque speakers—in formal situations (education, mass media, literature), and this is its main use today. In both Spain and France, the use of Basque for education varies from region to region and from school to school.[13]

Basque is the only surviving Paleo-European language in Europe. The current mainstream scientific view on the origin of the Basques and of their language is that early forms of Basque developed before the arrival of Indo-European languages in the area, i.e. before the arrival of Celtic, and Romance languages in particular, as the latter today geographically surround the Basque-speaking region. Typologically, with its agglutinative morphology and ergative–absolutive alignment, Basque grammar remains markedly different from that of Standard Average European languages. Nevertheless, Basque has borrowed up to 40 percent of its vocabulary from Romance languages,[14] and the Latin script is used for the Basque alphabet.

Names of the language

[edit]In Basque, the name of the language is officially euskara (alongside various dialect forms).

In French, the language is normally called basque though euskara has become common in recent times. Spanish has a greater variety of names for the language. Today, it is most commonly referred to as vasco, lengua vasca, or euskera. Both terms, vasco and basque, are inherited from the Latin ethnonym Vascones, which in turn goes back to the Greek term Οὐάσκωνες (ouáskōnes), an ethnonym used by Strabo in his Geographica (23 CE, Book III).[15]

The Spanish term vascuence, derived from Latin vasconĭce,[16] has acquired negative connotations over the centuries and is not well-liked amongst Basque speakers generally. Its use is documented at least as far back as the 14th century when a law passed in Huesca in 1349 stated that Item nuyl corridor nonsia usado que faga mercadería ninguna que compre nin venda entre ningunas personas, faulando en algaravia nin en abraych nin en basquenç: et qui lo fara pague por coto XXX sol—essentially penalising the use of Arabic, Hebrew, or Basque in marketplaces with a fine of 30 sols (the equivalent of 30 sheep).[17]

History and classification

[edit]Despite the Basque language being geographically surrounded by Romance languages, it is a language isolate that is unrelated to them or to any other living language. Most scholars believe Basque to be the last remaining descendant of one of the pre-Indo-European languages of prehistoric Europe.[15] Consequently, it may be impossible to reconstruct the prehistory of the Basque language by the traditional comparative method except by applying it to differences between Basque dialects. Little is known of its origins, but it is likely that an early form of the Basque language was present in and around the area of modern Basque Country before the arrival of the Indo-European languages in western Europe during the 3rd millennium BC.

Authors such as Miguel de Unamuno and Louis Lucien Bonaparte have noted that the words for "knife" (aizto), "axe" (aizkora), and "hoe" (aitzur) appear to derive from the word for "stone" (haitz), and have therefore concluded that the language dates to prehistoric Europe when those tools were made of stone.[18][19] Others find this theory unlikely.

Latin inscriptions in Gallia Aquitania preserve a number of words with cognates in the reconstructed proto-Basque language, for instance, the personal names Nescato and Cison (neskato and gizon mean 'young girl' and 'man', respectively in modern Basque). This language is generally referred to as Aquitanian and is assumed to have been spoken in the area before the Roman Republic's conquests in the western Pyrenees. Some authors even argue for late Basquisation, that the language moved westward during Late Antiquity after the fall of the Western Roman Empire into the northern part of Hispania into what is now the Basque Country.[15]

Roman neglect of this area allowed Aquitanian to survive while the Iberian and Tartessian languages became extinct. Through the long contact with Romance languages, Basque adopted a sizeable number of Romance words. Initially the source was Latin, later Gascon (a branch of Occitan) in the north-east, Navarro-Aragonese in the south-east and Spanish in the south-west.

Since 1968, Basque has been immersed in a revitalisation process, facing formidable obstacles. However, significant progress has been made in numerous areas. Six main factors have been identified to explain its relative success:

- implementation and acceptance of Unified Basque (Batua),

- integration of Basque in the education system

- creation of media in Basque (radio, newspapers, and television)

- the established new legal framework

- collaboration between public institutions and people's organisations, and

- campaigns for Basque language literacy.[20]

While those six factors influenced the revitalisation process, the extensive development and use of language technologies is also considered a significant additional factor.[21]

Hypotheses concerning Basque's connections to other languages

[edit]Many linguists have tried to link Basque with other languages, but no hypothesis has gained mainstream acceptance. Apart from pseudoscientific comparisons, the appearance of long-range linguistics gave rise to several attempts to connect Basque with geographically very distant language families such as Georgian. Historical work on Basque is challenging since written material and documentation has been available only for some few hundred years. Almost all hypotheses concerning the origin of Basque are controversial, and the suggested evidence is not generally accepted by mainstream linguists. Some of these hypothetical connections are:

- Ligurian substrate: this hypothesis, proposed in the 19th century by d'Arbois de Jubainville, J. Pokorny, P. Kretschmer and several other linguists, encompasses the Basco-Iberian hypothesis.

- Iberian: another ancient language once spoken in the Iberian Peninsula, shows several similarities with Aquitanian and Basque. However, most scholars say that there is not enough evidence to distinguish geographical connections from linguistic ones. Iberian itself remains unclassified. Eduardo Orduña Aznar claims to have established correspondences between Basque and Iberian numerals[22] and noun case markers. Other scholars have also claimed to identify a similarity between Iberian and Basque.[23]

- Vasconic substratum hypothesis: this proposal, made by the German linguist Theo Vennemann, claims that enough toponymical evidence exists to conclude that Basque is the only survivor of a larger family that once extended throughout most of western Europe, and has also left its mark in modern Indo-European languages spoken in Europe.

- Georgian: linking Basque to the Kartvelian languages is now widely discredited. The hypothesis was inspired by the existence of the ancient Kingdom of Iberia in the Caucasus and some similarities in societal practices and agriculture between the two populations. Historical comparisons are difficult due to the dearth of historical material for Basque and several of the Kartvelian languages. Typological similarities have been proposed for some of the phonological characteristics and most importantly for some of the details of the ergative constructions, but they alone cannot prove historical relatedness between languages since such characteristics are found in other languages across the world, even if not in Indo-European.[24][25] According to J. P. Mallory, the hypothesis was also inspired by a Basque place-name ending in -dze which is common in Kartvelian.[26] The hypothesis suggested that Basque and Georgian were remnants of a pre-Indo-European group.

- Northeast Caucasian languages, such as Chechen, are seen by some linguists as more likely candidates for a very distant connection.[27]

- Dené–Caucasian: based on the possible Caucasian link, some linguists, for example John Bengtson and Merritt Ruhlen, have proposed including Basque in the Dené–Caucasian superfamily of languages, but the proposed superfamily includes languages from North America and Eurasia, and its existence is highly controversial.[15]

- Indo-European: a genetic link between Basque and the Indo-European languages has been proposed by Forni (2013),[28][29] Blevins (2018),[30] though their contributions to the hypothesis have been rejected by most reviewers,[31][32][33][34][35][36] both including scholars adhering to the mainstream view of Basque as a language isolate (Gorrochategui, Lakarra) and proponents of wide-range genetic relations (Bengtson).

Geographic distribution

[edit]

The region where Basque is spoken has become smaller over centuries, especially at the northern, southern, and eastern borders. Nothing is known about the limits of the region in ancient times but on the basis of toponyms and epigraphs, it seems that in the beginning of the Common Era it stretched to the river Garonne in the north (including the south-western part of present-day France); at least to the Val d'Aran in the east (now a Gascon-speaking part of Catalonia), including lands on both sides of the Pyrenees;[37] the southern and western boundaries are not clear at all.

The Reconquista temporarily counteracted that contracting tendency when the Christian lords called on northern Iberian peoples (Basques, Asturians, and "Franks") to colonise the new conquests.

By the 16th century, the Basque-speaking area was reduced basically to the present-day seven provinces of the Basque Country, excluding the southern part of Navarre, the south-western part of Álava, and the western part of Biscay, and including some parts of Béarn.[38]

In 1807, Basque was still spoken in the northern half of Álava—including its capital city Vitoria-Gasteiz[39]—and a vast area in central Navarre, but in those two provinces, Basque experienced a rapid decline that pushed its border northwards. In the French Basque Country, Basque was still spoken in all the territory except in Bayonne and some villages around, and including some bordering towns in Béarn.

In the 20th century, however, the rise of Basque nationalism spurred increased interest in the language as a sign of ethnic identity, and with the establishment of autonomous governments in the Southern Basque Country, it has recently made a modest comeback. In the Spanish part, Basque-language schools for children and Basque-teaching centres for adults have brought the language to areas such as western Enkarterri and the Ribera del Ebro in southern Navarre, where it is not known to ever have been widely spoken; and in the French Basque Country, those schools and centres have almost stopped the decline of the language.

Official status

[edit]

Historically, Latin or Romance languages have been the official languages in the region. However, Basque was explicitly recognised in some areas. For instance, the fuero or charter of the Basque-colonised Ojacastro (now in La Rioja) allowed the inhabitants to use Basque in legal processes in the 13th and 14th centuries. Basque was allowed in telegraph messages in Spain thanks to the royal decree of 1904.[40]

The Spanish Constitution of 1978 states in Article 3 that the Spanish language is the official language of the nation, but allows autonomous communities to provide a co-official language status for the other languages of Spain.[41] Consequently, the Statute of Autonomy of the Basque Autonomous Community establishes Basque as the co-official language of the autonomous community. The Statute of Navarre establishes Spanish as the official language of Navarre, but grants co-official status to the Basque language in the Basque-speaking areas of northern Navarre. Basque has no official status in the French Basque Country and French citizens are barred from officially using Basque in a French court of law. However, the use of Basque by Spanish nationals in French courts is permitted (with translation), as Basque is officially recognised on the other side of the border.

The positions of the various existing governments differ with regard to the promotion of Basque in areas where Basque is commonly spoken. The language has official status in those territories that are within the Basque Autonomous Community, where it is spoken and promoted heavily but only partially in Navarre. The Ley del Vascuence ('Law of Basque'), seen as contentious by many Basques, but considered fitting Navarra's linguistic and cultural diversity by some of the main political parties of Navarre,[42] divides Navarre into three language areas: Basque-speaking, non-Basque-speaking, and mixed. Support for the language and the linguistic rights of citizens vary, depending on the area. Others consider it unfair, since the rights of Basque speakers differ greatly depending on the place they live.

Demographics

[edit]

The 2021 sociolinguistic survey of all Basque-speaking territories showed that, of all people aged 16 and above:[1]

- In the Basque Autonomous Community, 36.2% were fluent Basque speakers, 18.5% passive speakers and 45.3% did not speak Basque. The percentage was highest in Gipuzkoa (51.8% speakers) and Bizkaia (30.6%) and lowest in Álava (22.4%). Those results represent an increase from previous years (33.9% in 2016, 30.1% in 2006, 29.5% in 2001, 27.7% in 1996 and 24.1% in 1991). The highest concentration of speakers can now be found in the 16–24 age range (74.5%) vs. 22.0% in the 65+ age range.

- In the French Basque Country, in 2021, 20.0% were fluent Basque speakers. Because the French Basque Country is not under the influence of the Basque Autonomous Country government, people in the region have fewer incentives from government authorities to learn the language. As such, those results represent another decrease from previous years (22.5% in 2006, 24.8% in 2001 and 26.4 in 1996 or 56,146 in 1996 to 51,197 in 2016). However, for those in the 16-24 age range, the proportion of Basque speakers increased to 21.5%, from 12.2% 20 years earlier.

- In Navarre, 14.1% were fluent Basque speakers, 10.5% passive speakers, and 75.4% did not speak Basque. The percentage was highest in the Basque-speaking zone in the north (62.3% speakers, including 85.9% of youth) and lowest in the non-Basque-speaking zone in the south (1.6%). The overall proportion of 14.1% represented a slight increase from previous years (12.9% in 2016, 11.1% in 2006,10.3% in 2001, 9.6% in 1996 and 9.5% in 1991). Among age groups, the highest percentage of speakers can now be found in the 16–24 age range (28%) vs. 8.3% in the 65+ age range.

In 2021, out of a population of 2,634,800 over 16 years of age (1,838,800 in the Autonomous community, 546,000 in Navarre and 250,000 in the Northern Basque Country), 806,000 spoke Basque, which amounted to 30.6% of the population. Compared to the 1991 figures, that represents an overall increase of 266,000, from 539,110 speakers 30 years previously (430,000 in the BAC,[clarification needed] 40,110 in FCN,[clarification needed] and 69,000 in the Northern provinces). The number has tended to increase, as in all regions the age group most likely to speak Basque was those between 16 and 24 years old. In the BAC, the proportion in that age group that spoke the language (74.5%) was nearly triple the comparable figure from 1991, when barely a quarter of the population spoke Basque.[1]

While there is a general increase in the number of Basque speakers during the period, that is mainly because of bilingualism. Basque transmission as a sole mother tongue has decreased from 19% in 1991 to 15.1% in 2016, and Basque and another language being used as mother language increased from 3% to 5.4% in the same time period. General public attitude towards efforts to promote the Basque language have also been more positive, with the share of people against those efforts falling from 20.9% in 1991 to 16% in 2016.[43]

In 2021, the study found that in the BAC, when both parents were Basque speakers, 98% of children were communicated to only in Basque, and 2% were communicated to in both Basque and Spanish. When only one parent was a Basque-speaker and had Basque as a first language, 84% used Basque and Spanish and 16% only Spanish. In Navarre, the family language of 94.3% of the youngest respondents with both Basque parents was Basque. In the Northern Basque Country, however, when both parents were Basque-speaking, just two thirds transmitted only Basque to their offspring, and as age decreased, the transmission rate also decreased.[1]

| Across all | BAC | Navarre | FBC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991[44] | 22.3% | 24.1% | 9.5% | - |

| 1996[44] | 24.4% ( |

27.7% ( |

9.6% ( |

26.4% |

| 2001[44] | 25.4% ( |

29.4% ( |

10.3% ( |

24.8% ( |

| 2006[44] | 25.7% ( |

30.1% ( |

11.1% ( |

22.5% ( |

| 2011[45] | 27.0% ( |

32.0% ( |

11.7% ( |

21.4% ( |

| 2016[43] | 28.4% ( |

33.9% ( |

12.9% ( |

20.5% ( |

| 2021[1] | 30.6% ( |

36.2% ( |

14.1% ( |

20.0% ( |

Basque is used as a language of commerce both in the Basque Country and in locations around the world where Basques immigrated throughout history.[46]

Dialects

[edit]

The modern Basque dialects show a high degree of dialectal divergence, sometimes making cross-dialect communication difficult. That is especially true in the case of Biscayan and Souletin, which are regarded as the most divergent Basque dialects.

Modern Basque dialectology distinguishes five dialects:[47]

Those dialects are divided in 11 subdialects, and 24 minor varieties among them. According to Koldo Zuazo,[48] the Biscayan dialect or "Western" is the most widespread dialect, with around 300,000 speakers out of a total of around 660,000 speakers. The dialect is divided in two minor subdialects (Western Biscayan and Eastern Biscayan), as well as transitional dialects.

Influence on other languages

[edit]Although the influence of the neighbouring Romance languages on the Basque language (especially the lexicon, but also to some degree Basque phonology and grammar) has been much more extensive, it is usually assumed that there has been some influence from Basque into those languages as well. Gascon and Aragonese particularly and Spanish to a lesser degree are thought to have received Basque influence in the past. In the cases of Aragonese and Gascon, that would have been through substrate interference following language shift from Aquitanian or Basque to a Romance language that has affected all levels of the language, including place names around the Pyrenees.[49][50][51][52][53]

Although a number of words of alleged Basque origin in Spanish are circulated (e.g. anchoa 'anchovies', bizarro 'dashing, gallant, spirited', cachorro 'puppy', etc.), most of them have more easily-explained Romance etymologies or not particularly-convincing derivations from Basque.[15] Ignoring cultural terms, there is one strong loanword candidate, ezker, long considered the source of the Pyrenean and Iberian Romance words for "left (side)" (izquierdo, esquerdo, esquerre).[15][54] The lack of initial /r/ in Gascon could arguably be from Basque influence, but that issue is under-researched.[15]

There are other most commonly-claimed substrate influences:

- the Old Spanish merger of /v/ and /b/.

- the simple five-vowel system.

- change of initial /f/ into /h/ (e.g. fablar → hablar, with Old Basque lacking /f/ but having /h/).

- voiceless alveolar retracted sibilant [s̺], a sound transitional between laminodental [s] and palatal [ʃ]; this sound also influenced other Ibero-Romance languages and Catalan.

The first two features are common, widespread developments in many Romance (and non-Romance) languages.[15][specify] The change of /f/ to /h/ occurred historically only in limited areas (Gascony and northern Old Castile), which correspond almost exactly to the places where heavy Basque bilingualism in the past is assumed and, as a result, has been widely postulated and equally strongly disputed. Substrate theories are often difficult to prove (especially in the case of phonetically-plausible changes like /f/ to /h/). As a result, many arguments have been made on both sides, but the debate largely comes down to the a priori tendency on the part of particular linguists to accept or reject substrate arguments.

Examples of arguments against the substrate theory[15] and possible responses:

- Spanish did not fully shift /f/ to /h/; instead, it has preserved /f/ before consonants such as /w/ and /ɾ/ (cf fuerte, frente). (On the other hand, the occurrence of [f] in those words might be a secondary development from an earlier sound such as [h] or [ɸ] and learned words or words influenced by written Latin form. Gascon has /h/ in these words, which might reflect the original situation.)

- Evidence of Arabic loanwords in Spanish points to /f/ continuing to exist long after a Basque substrate might have had any effect on Spanish. (On the other hand, the occurrence of /f/ in those words might be a late development. Many languages have come to accept new phonemes from other languages after a period of significant influence. For example, French lost /h/ but later regained it as a result of Germanic influence, and it has recently gained /ŋ/ as a result of English influence.)

- Basque regularly developed Latin /f/ into /b/ or /p/.

- The same change also occurs in parts of Sardinia, Italy and the Romance languages of the Balkans where no Basque substrate can be reasonably argued for. (On the other hand, the fact that the same change might have occurred elsewhere independently does not disprove substrate influence. Furthermore, parts of Sardinia also have prothetic /a/ or /e/ before initial /r/, just as in Basque and Gascon, which may actually argue for some type of influence between both areas.)

Some examples in the initial position are for example, /v/ in Latin vulture, which became the /p/ of putre; initial Spanish /b/ of bolsa, "purse" also converged to a voiceless in Basque poltsa, while /p/ of Latin pace[m], "peace" has evolved into the reverse direction, the voicing sound /b/ of bake, or Latin pica[m], "magpie", which didn't change anything as pika. Latin /f/ of ficus, "fig" or fagus, "beech" changed also into /p/ piku and pago. Each parallelism depends on phonetic evolutions, the time of the borrowing, and the language from which it was loaned (Latin, Late Latin, Early Romance, Spanish, French or others). The same could be said for the borrowings in the reverse direction.

Beyond those arguments, a number of nomadic groups of Castile are also said to use or have used Basque words in their jargon, such as the gacería in Segovia, the mingaña, the Galician fala dos arxinas[55] and the Asturian Xíriga.[56]

Part of the Romani community in the Basque Country speaks Erromintxela, which is a rare mixed language, with a Kalderash Romani vocabulary and Basque grammar.[57]

Basque pidgins

[edit]A number of Basque-based or Basque-influenced pidgins have existed. In the 16th century, Basque sailors used a Basque–Icelandic pidgin in their contacts with Iceland.[58] The Algonquian–Basque pidgin arose from contact between Basque whalers and the Algonquian peoples in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and Strait of Belle Isle.[59]

Phonology

[edit]Vowels

[edit]| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i /i/ |

u /u/ | |

| Mid | e /e/ |

o /o/ | |

| Open | a /a/ |

The Basque language features five vowels: /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/ and /u/ (the same that are found in Spanish, Asturian and Aragonese). In the Zuberoan dialect, extra phonemes are featured:

- the close front rounded vowel /y/, graphically represented as ⟨ü⟩;

- a set of contrasting nasal vowels.

There is no distinctive vowel length in Basque although vowels may be lengthened for emphasis. The mid vowels /e/ and /o/ are raised before nasal consonants.[60]

Basque has an elision rule according to which the vowel /a/ is elided before any following vowel.[61] That does not prevent the existence of diphthongs with /a/ present.

| IPA | Example | Meaning | IPA | Example | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /ai̯/ | bai | yes | /au̯/ | gau | night |

| /ei̯/ | sei | six | /eu̯/ | euri | rain |

| /oi̯/ | oin | foot | |||

| /ui̯/ | fruitu | fruit |

There are six diphthongs in Basque, all falling and with /i̯/ or /u̯/ as the second element.[62]

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Lamino- dental |

Apico- alveolar |

Palatal or postalveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m /m/ |

n /n/ |

ñ, -in- /ɲ/ |

||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p /p/ |

t /t/ |

tt, -it- /c/ |

k /k/ |

||

| voiced | b /b/ |

d /d/ |

dd, -id- /ɟ/ |

g /ɡ/ |

|||

| Affricate | tz /t̻s̻/ |

ts /t̺s̺/ |

tx /tʃ/ |

||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f /f/ |

z /s̻/ |

s /s̺/ |

x /ʃ/ |

h /∅/, /h/ | |

| (mostly)1 voiced | j /j/~/x/ |

||||||

| Lateral | l /l/ |

ll, -il- /ʎ/ |

|||||

| Rhotic[a] | Trill | r-, -rr-, -r /r/ |

|||||

| Tap | -r-, -r /ɾ/ |

||||||

- ^ Basque's two rhotics contrast only between vowels, and the trill is then written as -rr- and the tap as -r-. When a suffix is added to a word ending in -r, a trill is generally used, as in ederrago 'more beautiful', from eder 'beautiful' and -ago. There is a small number of words that are exceptions to the rule, with de Rijk listing the following ten common ones: zer, ezer, nor, inor, hor, paper, plater, plazer, ur, and zur.[63]

In syllable-final position, all plosives are devoiced and are spelled accordingly in Standard Basque. When between vowels, and often when after /r/ or /l/, the voiced plosives /b/, /d/, and /ɡ/, are pronounced as the corresponding fricatives [β], [ð], and [ɣ].[62]

Basque has a distinction between laminal and apical articulation for the alveolar fricatives and affricates. With the laminal alveolar fricative [s̻], the friction occurs across the blade of the tongue, the tongue tip pointing toward the lower teeth. That is the usual /s/ in most European languages and is written with an orthographic ⟨z⟩. In contrast, the voiceless apicoalveolar fricative [s̺] is written ⟨s⟩; the tip of the tongue points toward the upper teeth and friction occurs at the tip (apex). For example, zu 'you' (singular, respectful) is distinguished from su 'fire'. The affricate counterparts are written ⟨tz⟩ and ⟨ts⟩. So, etzi 'the day after tomorrow' is distinguished from etsi 'to give up'; atzo 'yesterday' is distinguished from atso 'old woman'.[64]

In the westernmost parts of the Basque country, only the apical ⟨s⟩ and the alveolar affricate ⟨tz⟩ are used.

Basque also features postalveolar sibilants (/ʃ/, written ⟨x⟩, and /tʃ/, written ⟨tx⟩).[65]

The letter ⟨j⟩ has a variety of realisations according to the regional dialect: [j, dʒ, x, ʃ, ɟ, ʝ], as pronounced from west to east in south Bizkaia and coastal Lapurdi, central Bizkaia, east Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, south Navarre, inland Lapurdi and Low Navarre, and Zuberoa, respectively.[66]

The letter ⟨h⟩ is pronounced in the northern dialects but not in the southern ones. Unified Basque spells it except when it is predictable, after a consonant.[clarification needed][67]

Unless they are recent loanwords (e.g. Ruanda 'Rwanda', radar, robot ... ), words may not have initial ⟨r⟩. In older loans, initial r- took a prosthetic vowel, resulting in err- (Erroma 'Rome', Errusia 'Russia'), more rarely irr- (for example irratia 'radio', irrisa 'rice') and arr- (for example arrazional 'rational').[68]

Basque does not have /m/ in syllable final position, and syllable-final /n/ assimilates to the place of articulation of following plosives. As a result, /nb/ is pronounced like [mb], and /nɡ/ is realized as [ŋɡ].[69]

Palatalization

[edit]Basque has two types of palatalization, automatic palatalization and expressive palatalization. Automatic palatalization occurs in western Labourd, much of Navarre, all of Gipuzkoa, and nearly all of Biscay. As a result of automatic palatalization, /n/ and /l/ become the palatal nasal [ɲ] and the palatal lateral [ʎ] respectively after the vowel /i/ and before another vowel. An exception is the loanword lili 'lily'. The same palatalization occurs after the semivowel [j] of the diphthongs ai, ei, oi, ui. The palatalization occurs in a wider area, including Soule, all of Gipuzkoa and Biscay, and almost all of Navarre. In a few regions, /n/ and /l/ can be palatalized even in the absence of a following vowel. After palatalization, the semivowel [j] is usually absorbed by the palatal consonant. That can be seen in older spellings, such as malla instead of modern maila 'degree'. However, the modern orthography for Standard Basque ignores automatic palatalization.[70]

In certain regions of Gipuzkoa and Biscay, intervocalic /t/ is often palatalized after /i/ and especially [j]. It may become indistinguishable from the affricate /tʃ/,[71] spelled ⟨tx⟩, so aita 'father' may sound like it were spelled atxa or atta.[72] That type of palatalization is far from general, and is often viewed as substandard.[71]

In Goizueta Basque, there are a few examples of /nt/ being palatalized after /i/, and optional palatalization of /ld/. For example, mintegi 'seedbed' becomes [mincei], and bildots 'lamb' can be /biʎots̺/.[72]

Basque nouns, adjectives, and adverbs can be expressively palatalized and express 'smallness', rarely literal; they often show affection in nouns and mitigation in adjectives and adverbs. That is often used in the formation of pet names and nicknames. In words containing one or more sibilant, those sibilants are palatalized to form the palatalized form. That is, s and z become x, and ts and tz become tx. As a result, gizon 'man' becomes gixon 'little fellow', zoro 'crazy, insane' becomes xoro 'silly, foolish', and bildots 'lamb' becomes bildotx 'lambkin, young lamb'.

In words without sibilants, /t/, /d/, /n/, and /l/ can become palatalized, which is indicated in writing with a double consonant except in the case of palatalized /n/, which is written ⟨ñ⟩. Thus, tanta 'drop' becomes ttantta 'droplet', and nabar 'grey' becomes ñabar 'grey and pretty, greyish'.[71]

The pronunciation of tt and dd, and the existence of dd, differ by dialect. In the Gipuzkoan and Biscayan dialects tt is often pronounced the same as tx, that is, as [tʃ], and dd does not exist.[71] Likewise, in Goizueta Basque, tt is a voiceless palatal stop [c] and the corresponding voiced palatal stop, [ɟ], is absent except as an allophone of /j/. In Goizueta Basque, /j/ is sometimes the result of an affectionate palatalization of /d/.[73]

Palatalization of the rhotics is rare and occurs only in the eastern dialects. When palatalized, the rhotics become the palatal lateral [ʎ]. Likewise, palatalization of velars, resulting in tt or tx, is quite rare.[74]

A few common words, such as txakur 'dog', pronounced /tʃakur/, use palatal sounds even though in current usage, they have lost the diminutive sense, the corresponding non-palatal forms now acquiring an augmentative or pejorative sense: zakur 'big dog'.[74]

Sandhi

[edit]There are some rules governing the behaviour of consonants in contact with each other and apply both within and between words. When two plosives meet, the first one is dropped, and the second becomes voiceless. If a sibilant follows a plosive, the plosive is dropped, and the sibilant becomes the corresponding affricate. When a plosive follows an affricate, the affricate becomes a sibilant, and a voiced plosive is devoiced. When a voiced plosive follows a sibilant, it is devoiced except in very slow and careful speech. In the central dialects of Basque, a sibilant turns into an affricate if it follows a liquid or a nasal. When a plosive follows a nasal, there is a strong tendency for it to become voiced.[75]

Stress and pitch

[edit]Basque features great dialectal variation in accentuation, from a weak pitch accent in the western dialects to a marked stress in central and eastern dialects, with varying patterns of stress placement.[76]

Stress is in general not distinctive (and for historical comparisons not very useful); there are, however, a few instances in which stress is phonemic, serving to distinguish between a few pairs of stress-marked words and between some grammatical forms (mainly plurals from other forms), e.g. basóà ('the forest', absolutive case) vs. básoà ('the glass', absolutive case; an adoption from Spanish vaso); basóàk ('the forest', ergative case) vs. básoàk ('the glass', ergative case) vs. básoak ('the forests' or 'the glasses', absolutive case).

Given its great deal of variation among dialects, stress is not marked in the standard orthography and Euskaltzaindia (the Academy of the Basque Language) provides only general recommendations for a standard placement of stress, basically to place a high-pitched weak stress (weaker than that of Spanish, let alone that of English) on the second syllable of a syntagma, and a low-pitched even-weaker stress on its last syllable, except in plural forms in which stress is moved to the first syllable.

That scheme provides Basque with a distinct musicality that differentiates its sound from the prosodical patterns of Spanish (which tends to stress the second-last syllable). Some Euskaldun berriak ('new Basque-speakers', i.e. second-language Basque-speakers) with Spanish as their first language tend to carry the prosodical patterns of Spanish into their pronunciation of Basque, e.g. pronouncing nire ama ('my mum') as nire áma (– – ´ –), instead of as niré amà (– ´ – `).

Morphophonology

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2016) |

The combining forms of nominals in final /-u/ vary across the regions of the Basque Country. The /u/ can stay unchanged, be lowered to an /a/, or it can be lost. Loss is most common in the east, while lowering is most common in the west. For instance, buru, 'head', has the combining forms buru- and bur-, as in buruko, 'cap', and burko, 'pillow', whereas katu, 'cat', has the combining form kata-, as in katakume, 'kitten'. Michelena suggests that the lowering to /a/ is generalised from cases of Romance borrowings in Basque that retained Romance stem alternations, such as kantu, 'song' with combining form kanta-, borrowed from Romance canto, canta-.[77]

Grammar

[edit]Basque is an ergative–absolutive language. The subject of an intransitive verb is in the absolutive case (which is unmarked), and the same case is used for the direct object of a transitive verb. The subject of the transitive verb is marked differently, with the ergative case (shown by the suffix -k). That also triggers main and auxiliary verbal agreement.

The auxiliary verb, which accompanies most main verbs, agrees not only with the subject but also with any direct or indirect object present. Among European languages, the polypersonal agreement is found only in Basque, some languages of the Caucasus (especially the Kartvelian languages), Mordvinic languages, Hungarian, and Maltese (all non-Indo-European). The ergative–absolutive alignment is also rare among European languages and occurs only in some languages of the Caucasus but is frequent worldwide.

Consider the phrase:

Martin-ek

Martin-ERG

egunkari-ak

newspaper-PL.ABS

erosten

buy-GER

di-zki-t

AUX.3.OBJ-PL.OBJ-me.IO[3SG_SBJ]

"Martin buys the newspapers for me."

Martin-ek is the agent (transitive subject), so it is marked with the ergative case ending -k (with an epenthetic -e-). Egunkariak has an -ak ending, which marks plural object (plural absolutive, direct object case). The verb is erosten dizkit, in which erosten is a kind of gerund ("buying") and the auxiliary dizkit means "he/she (does) them for me". The dizkit can be divided like this:

- di- is used in the present tense when the verb has a subject (ergative), a direct object (absolutive), and an indirect object, and the object is him/her/it/them.

- -zki- means the absolutive (in this case the newspapers) is plural; if it were singular there would be no infix; and

- -t or -da- means "to me/for me" (indirect object).

- in this instance there is no suffix after -t. A zero suffix in this position indicates that the ergative (the subject) is third person singular (he/she/it).

Zu-ek

you-ERG(PL)

egunkari-ak

newspaper-PL

erosten

buy-GER

di-zki-da-zue

AUX.3.OBJ-PL.OBJ-me.IO-you(PL).SBJ

"You (plural) buy the newspapers for me."

The auxiliary verb is composed as di-zki-da-zue' and means 'you pl. (do) them for me'.

- di- indicates that the main verb is transitive and in the present tense

- -zki- indicates that the direct object is plural

- -da- indicates that the indirect object is me (to me/for me; -t becomes -da- unless final)

- -zue indicates that the subject is you (plural)

The pronoun zuek 'you (plural)' has the same form both in the nominative or absolutive case (the subject of an intransitive sentence or direct object of a transitive sentence) and in the ergative case (the subject of a transitive sentence). In spoken Basque, the auxiliary verb is never dropped even if it is redundant: dizkidazue in zuek niri egunkariak erosten dizkidazue 'you (pl.) are buying the newspapers for me'. However, the pronouns are almost always dropped: zuek in egunkariak erosten dizkidazue 'you (pl.) are buying the newspapers for me'. The pronouns are used only to show emphasis: egunkariak zuek erosten dizkidazue 'it is you (pl.) who buys the newspapers for me', or egunkariak niri erosten dizkidazue 'it is me for whom you buy the newspapers'.

Modern Basque dialects allow for the conjugation of about fifteen verbs, called synthetic verbs, some occurring only in literary contexts. They can exist in the present and the past tenses in the indicative and the subjunctive moods, in three tenses in the conditional and the potential moods, and in one tense in the imperative. Each verb that can be taken intransitively has a nor (absolutive) paradigm and possibly a nor-nori (absolutive–dative) paradigm, as in the sentence Aititeri txapela erori zaio ('The hat fell from grandfather['s head]').[78] Each verb that can be taken transitively uses those two paradigms for antipassive-voice contexts in which no agent is mentioned (Basque lacks a passive voice, and displays instead an antipassive voice paradigm), and also has a nor-nork (absolutive–ergative) paradigm and possibly a nor-nori-nork (absolutive–dative–ergative) paradigm. The last is exemplified by dizkidazue above. In each paradigm, each constituent noun can take on any of eight persons, five singular and three plural, with the exception of nor-nori-nork in which the absolutive can be only third-person singular or plural. The most ubiquitous auxiliary, izan, can be used in any of those paradigms, depending on the nature of the main verb.

There are more persons in the singular (5) than in the plural (3) for synthetic (or filamentous) verbs because of the two familiar persons—informal masculine and feminine second-person singular. The pronoun hi is used for both of them, but though the masculine form of the verb uses a -k, the feminine uses an -n. That is a property rarely found in Indo-European languages. The entire paradigm of the verb is further augmented by inflecting for "listener" (the allocutive) even if the verb contains no second person constituent. If the situation calls for the familiar masculine, the form is augmented and modified accordingly and likewise for the familiar feminine.

(Gizon bat etorri da, 'a man has come'; gizon bat etorri duk, 'a man has come [you are a male close friend]', gizon bat etorri dun, 'a man has come [you are a female close friend]', gizon bat etorri duzu, 'a man has come [I talk to you (Sir / Madam)]')[79] That multiplies the number of possible forms by nearly three. Still, the restriction on contexts in which those forms may be used is strong since all participants in the conversation must be friends of the same sex and not too far apart in age. Some dialects dispense with the familiar forms entirely, but the formal second-person singular conjugates in parallel to the other plural forms, which perhaps indicates that it was originally the second-person plural and later came to be used as a formal singular, and the modern second-person plural was formulated only later as an innovation.

All other verbs in Basque are called periphrastic and behave much as participles would in English. They have only three forms in total, called aspects: perfect (various suffixes), habitual[80] (suffix -t[z]en), and future/potential (suffix. -ko/-go). Verbs of Latinate origin in Basque, as well as many other verbs, have a suffix -tu in the perfect, adapted from the Latin perfect passive -tus suffix. The synthetic verbs also have periphrastic forms, for use in perfects and in simple tenses in which they are deponent.

Within a verb phrase, the periphrastic verb comes first, followed by the auxiliary.

A Basque noun phrase is inflected in 17 different ways for case, multiplied by four ways for its definiteness and number (indefinite, definite singular, definite plural, and definite close plural: euskaldun [Basque-speaker], euskalduna [the Basque speaker, a Basque-speaker], euskaldunak [Basque-speakers, the Basque-speakers], and euskaldunok [we Basque speakers, those Basque-speakers]). The first 68 forms are further modified based on other parts of the sentence, which in turn are inflected for the noun again. It has been estimated that with two levels of recursion, a Basque noun may have 458,683 inflected forms.[81]

| Word | Case | Result | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| etxe | Ø | etxe | house |

| etxe | a | etxea | the house |

| etxe | ak | etxeak | the houses |

| etxe | a + ra | etxera | to the house |

| etxe | ak + ra | etxeetara | to the houses |

| etxe | a + tik | etxetik | from the house |

| etxe | ak + tik | etxeetatik | from the houses |

| etxe | a + (r)aino | etxeraino | until the house |

| etxe | ak + (r)aino | etxeetaraino | until the houses |

| etxe | a + n | etxean | in the house |

| etxe | ak + n | etxeetan | in the houses |

| etxe | a + ko | etxeko | of the house (belonging to) |

| etxe | ak + ko | etxeetako | of the houses (belonging to) |

The common noun liburu 'book' is declined as follows:

| Case/Number | Singular | Plural | Undetermined |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolutive | liburu-a-Ø | liburu-ak | liburu-Ø |

| Ergative | liburu-a-k | liburu-e-k | liburu-k |

| Dative | liburu-a-ri | liburu-e-i | liburu-ri |

| Local genitive | liburu-ko | liburu-e-ta-ko | liburu-tako |

| Possessive genitive | liburu-a-ren | liburu-e-n | liburu-ren |

| Comitative (with) | liburu-a-rekin | liburu-e-kin | liburu-rekin |

| Benefactive (for) | liburu-a-rentzat | liburu-e-ntzat | liburu-rentzat |

| Causal (because of) | liburu-a-rengatik | liburu-e-ngatik | liburu-rengatik |

| Instrumental | liburu-a-z | liburu-etaz | liburu-taz |

| Inessive (in, on) | liburu-a-n | liburu-e-ta-n | liburu-tan |

| Ablative (from) | liburu-tik | liburu-e-ta-tik | liburu-tatik |

| Allative (where to: 'to') | liburu-ra | liburu-e-ta-ra | liburu-tara |

| Directive ('towards') | liburu-rantz | liburu-e-ta-rantz | liburu-tarantz |

| Terminative (up to) | liburu-raino | liburu-e-ta-raino | liburu-taraino |

| Prolative | liburu-tzat | ||

| Partitive | liburu-rik |

The proper name Mikel (Michael) is declined as follows:

| Word | Case | Result | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mikel | (r)en | Mikelen | of Mikel |

| Mikel | (r)engana | Mikelengana | to Mikel |

| Mikel | (r)ekin | Mikelekin | with Mikel |

Within a noun phrase, modifying adjectives follow the noun. As an example of a Basque noun phrase, etxe zaharrean 'in the old house' is morphologically analysed as follows by Agirre et al.[82]

| Word | Form | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| etxe | noun | house |

| zahar- | adjective | old |

| -r-e- | epenthetical elements | n/a |

| -a- | determinate, singular | the |

| -n | inessive case | in |

Basic word order in syntactic construction is subject–object–verb. The order of the phrases within a sentence can be changed for thematic purposes, whereas the order of the words within a phrase is usually rigid. As a matter of fact, Basque phrase order is topic–focus, meaning that in neutral sentences (such as sentences to inform someone of a fact or event) the topic is stated first, then the focus. In such sentences, the verb phrase comes at the end. In brief, the focus directly precedes the verb phrase. This rule is also applied in questions, for instance, What is this? can be translated as Zer da hau? or Hau zer da?, but in both cases the question tag zer immediately precedes the verb da. This rule is so important in Basque that, even in grammatical descriptions of Basque in other languages, the Basque word galdegai 'focus' is used.[clarification needed]

In negative sentences, the order changes. Since the negative particle ez must always directly precede the auxiliary, the topic most often comes beforehand, and the rest of the sentence follows. This includes the periphrastic, if there is one: Aitak frantsesa irakasten du, 'Father teaches French', in the negative becomes Aitak ez du frantsesa irakasten, in which irakasten ('teaching') is separated from its auxiliary and placed at the end.

Vocabulary

[edit]Through contact with neighbouring peoples, Basque has adopted many words from Latin, Spanish, French and Gascon, among other languages. There are a considerable number of Latin loans (sometimes obscured by being subject to Basque phonology and grammar for centuries), for example: lore ('flower', from florem), errota ('mill', from rotam, '[mill] wheel'), gela ('room', from cellam), gauza ('thing', from causa).[83]

Writing system

[edit]

Basque is written using the Latin script including ⟨ñ⟩ and sometimes ⟨ç⟩ and ⟨ü⟩. Basque does not use ⟨c, q, v, w, y⟩ for native words, but the Basque alphabet (established by Euskaltzaindia) does include them for loanwords:[84]

- ⟨Aa, Bb, Cc, Dd, Ee, Ff, Gg, Hh, Ii, Jj, Kk, Ll, Mm, Nn, Ññ, Oo, Pp, Qq, Rr, Ss, Tt, Uu, Vv, Ww, Xx, Yy, Zz⟩

The phonetically meaningful digraphs ⟨dd, ll, rr, ts, tt, tx, tz⟩ are treated as pairs of letters.

All letters and digraphs represent unique phonemes. The main exception is ⟨i⟩ if it precedes ⟨l⟩ and ⟨n⟩, which, in most dialects, palatalises their sounds into /ʎ/ and /ɲ/, even if they are not written. Hence, Ikurriña can also be written Ikurrina without changing the sound, and the proper name Ainhoa requires the mute ⟨h⟩ to break the palatalisation of the ⟨n⟩.

⟨h⟩ is mute in most regions but is pronounced in many places in the north-east, the main reason for its existence in the Basque alphabet. Its acceptance was a matter of contention during the standardisation process because the speakers of the most widespread dialects had to learn where to place ⟨h⟩, which was silent for them.

In Sabino Arana's (1865–1903) alphabet,[85] digraphs ⟨ll⟩ and ⟨rr⟩ were replaced with ⟨ĺ⟩ and ⟨ŕ⟩, respectively.

A typically Basque style of lettering is sometimes used for inscriptions. It derives from the work of stone and wood carvers and is characterised by thick serifs.

Number system used by millers

[edit]

Basque millers traditionally employed a separate number system of unknown origin.[86] In this system the symbols are arranged either along a vertical line or horizontally. On the vertical line the single digits and fractions are usually off to one side, usually at the top. When used horizontally, the smallest units are usually on the right and the largest on the left. As with the Basque system of counting in general, it is vigesimal (base 20). Although it is in theory capable of indicating numbers above 100, most recorded examples do not go above 100. Fractions are relatively common, especially 1⁄2.

The exact systems used vary from area to area but generally follow the same principle with 5 usually being a diagonal line or a curve off the vertical line (a V shape is used when writing a 5 horizontally). Units of ten are usually a horizontal line through the vertical. The twenties are based on a circle with intersecting lines. This system is no longer in general use but is occasionally employed for decorative purposes.

Examples

[edit]Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

[edit]| Gizon-emakume guztiak aske jaiotzen dira, duintasun eta eskubide berberak dituztela; eta ezaguera eta kontzientzia dutenez gero, elkarren artean senide legez jokatu beharra dute. | Basque pronunciation: [ɡis̻onemakume ɡus̻tiak as̺ke jajots̻en diɾa | duintas̺un eta es̺kubide berbeɾak ditus̻tela | eta es̻aɡueɾa eta konts̻ients̻ia dutenes̻ ɡeɾo | elkaren artean s̺enide leges̻ jokatu be(h)ara dute] | All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

Esklabu erremintaria

[edit]|

Esklabu erremintaria

|

IPA pronunciation

|

The blacksmith slave

|

| Joseba Sarrionandia | Joseba Sarrionandia |

Language video gallery

[edit]-

A Basque speaker

-

A Basque speaker, recorded in the Basque Country, Spain

-

A Basque speaker, recorded during Wikimania 2019

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "The Basque Language Gains Speakers, but No Surge in Usage – Basque Tribune". Archived from the original on 30 December 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ (in French) VI° Enquête Sociolinguistique en Euskal herria (Communauté Autonome d'Euskadi, Navarre et Pays Basque Nord) Archived 21 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine (2016).)

- ^ The data is the most recent available:

- from 2016 for Álava, Biscay and Gipuzkoa (VI Mapa Sociolingüístico, 2016, Basque Government)

- from 2018 for Navarre (Datos sociolingüísticos de Navarra, 2018, Government of Navarre)

- from 2016 for Labourd, Lower Navarre and Soule (L'enquête sociolinguistique de 2016, Mintzaira)

- ^ "Basque". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.); [bæsk] US; [bask] or [bɑːsk] UK

- ^ Porzucki, Nina (16 May 2018). "How the Basque language has survived". The World from PRX. theworld.org. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ Santiago de Pablo, "Lengua e identidad nacional en el País Vasco: Del franquismo a la democracia". In 'Le discours sur les langues d'Espagne : Edition français-espagnol', Christian Lagarde ed, Perpignan: Presses Universitaires de Perpignan, 2009, pp. 53-64, p. 53

- ^ See Jose Carlos Herreras, Actas XVI Congreso AIH. José Carlos HERRERAS. Políticas de normalización lingüística en la España democrática", 2007, p. 2. Reproduced in https://cvc.cervantes.es/literatura/aih/pdf/16/aih_16_2_021.pdf

- ^ See "Articulo 1, Orden Ministerial Sobre el Registro Civil, 18 de mayo de 1938". Reproduced in Jordi Busquets, "Casi Tres Siglos de Imposicion", 'El Pais' online, 29 April 2001. https://elpais.com/diario/2001/04/29/cultura/988495201_850215.html.

- ^ See Communicacion No. 2486, Negociado 4, Excelentisimo Gobierno Civil de Vizcaya, 27 Octubre de 1949". A letter of acknowledgement from the archive of the Alcaldia de Guernica y Lumo, 2 November 2941, is reproduced in https://radiorecuperandomemoria.com/2017/05/31/la-prohibicion-del-euskera-en-el-franquismo/ Archived 20 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ See for example the letter from the Military Commander of Las Arenas, Biscay, dated 21 October 1938, acknowledging a fine for the public use of a Basque first name on the streets of Las Arenas, reproduced in https://radiorecuperandomemoria.com/2017/05/31/la-prohibicion-del-euskera-en-el-franquismo/ Archived 20 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Francisco Franco". HISTORY. A&E Television Networks. 9 November 2009.

- ^ Clark, Robert (1979). The Basques: the Franco years and beyond. Reno: University of Nevada Press. p. 149. ISBN 0-874-17057-5.

- ^ "Navarrese Educational System. Report 2011/2012" (PDF). Navarrese Educative Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ "Basque Pidgin Vocabulary in European-Algonquian Trade Contacts." In Papers of the Nineteenth Algonquian Conference, edited by William Cowan, pp. 7–13. https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/ALGQP/article/download/967/851/0

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Trask, R.L. (1997). The History of Basque. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13116-2.

- ^ "Diccionario de la lengua española". Real Academia Española. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ^ O'Callaghan, J (1983). A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell Press. ISBN 978-0801492648.

- ^ Journal of the Manchester Geographical Society, volumes 52–56 (1942), page 90

- ^ Kelly Lipscomb, Spain (2005), page 457

- ^ Agirrezabal, Lore (2010). The basque experience : some keys to language and identity recovery. Eskoriatza, Gipuzkoa: Garabide Elkartea. ISBN 978-84-613-6835-8. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Alegria, Iñaki; Sarasola, Kepa (2017). Language technology for language communities: An overview based on our experience. In: FEL XXI : communities in control : learning tools and strategies for multilingual endangered language communities : proceedings of the 21st FEL Conference, 19-21 October 2017. Hungerford, England: Foundation for Endangered Languages. ISBN 978-0-9560210-9-0.

- ^ Orduña Aznar 2005.

- ^ Villamor, Fernando (2020), A BASIC DICTIONARY AND GRAMMAR OF THE IBERIAN LANGUAGE

- ^ Hualde, José Ignacio; Lakarra, Joseba; Trask, Robert Lawrence (1995). Towards a history of the Basque language. John Benjamins. p. 81. ISBN 90-272-3634-8.

- ^ Sturua, Natela (1991). "On the Basque-Caucasian Hypothesis". Studia Linguistica. 45 (1–2). Scandinavian University Press: 164–175. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9582.1991.tb00823.x.

- ^ Mallory, J. P. (1991). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth. Thames and Hudson.

- ^ Bengston, John D. (Spring 1996). "A Final (?) Response to the Basque Debate in Mother Tongue 1". Mother Tongue: Newsletter of the Association for the Study of Language In Prehistory. No. 26. Archived from the original on 13 March 2003.

- ^ Forni, Gianfranco (2013). "Evidence for Basque as an Indo-European Language". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 41 (1 & 2): 39–180. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ Forni, Gianfranco (January 2013). "Evidence for Basque as an Indo-European Language: A Reply to the Critics". Journal of Indo-European Studies: 268–310. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ Hualde, José Ignacio (2021). "On the Comparative Method, Internal Reconstruction, and Other Analytical Tools for the Reconstruction of the Evolution of the Basque Language: An Assessment". Anuario del Seminario de Filología Vasca "Julio de Urquijo". 54 (1–2): 19–52. doi:10.1387/asju.23021. hdl:10810/59003.

- ^ Kassian, Alexander (2013). "On Forni's Basque–Indo-European Hypothesis". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 41 (1 & 2): 181–201. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ Gorrochategui, Joaquín; Lakarra, Joseba A. (2013). "Why Basque cannot be, unfortunately, an Indo-European language?". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 41 (1 & 2): 203–237. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ Prósper, Blanca María (2013). "Is Basque an Indo-European language? Possibilities and limits of the comparative method when applied to isolates". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 41 (1 & 2): 238–245. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ Bengtson, John D. (2013). "Comments on "Evidence for Basque as an Indo-European Language" by Gianfranco Forni" (PDF). Journal of Indo-European Studies. 41 (1 & 2): 246–254. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ Koch, John T. (2013). "Is Basque an Indo-European Language?". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 41 (1 & 2): 255–267. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ Lakarra, Joseba A. (2017). "Prehistoria de la lengua vasca". In Gorrochategui Iván Igartua, Joaquín; Igartua, Iván; Lakarra, Joseba A. (eds.). Historia de la lengua vasca [History of the Basque language] (in Spanish). Vitoria-Gasteiz: Gobierno Vasco. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ Zuazo 2010, p. 16

- ^ Zuazo 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Zuazo, Koldo (2012). Arabako euskara. Andoain (Gipuzkoa): Elkar. p. 21. ISBN 978-84-15337-72-0.

- ^ The first telegraph message in Basque was sent by Teodoro de Arana y Beláustegui, at the time a deputy to the Cortes from Gipuzkoa, to Ondarroa; it read: Aitorreu hizcuntz ederrean nere lagun eta erritarrai bistz barrengo eroipenac (transl. heartfelt regards to my friends and compatriots in the wonderful language of Aitor), Diario de Reus 26.06.04

- ^ "Spanish Constitution". Spanish Constitutional Court. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ "Navarrese Parliament rejects to grant Basque Language co-official status in Spanish-speaking areas by suppressing the linguistic delimitation". Diario de Navarra. 16 February 2011. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ a b VI. Inkesta Soziolinguistikoa Gobierno Vasco, Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco 2016

- ^ a b c d Sixth Sociolinguistic Survey Gobierno Vasco, Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco 2016, ISBN 978-84-457-3502-2

- ^ V. Inkesta Soziolinguistikoa Gobierno Vasco, Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco 2003, ISBN 978-84-457-3303-5

- ^ Ray, Nina M. (1 January 2009). "Basque Studies: Commerce, Heritage, And A Language Less Commonly Taught, But Whole-Heartedly Celebrated". Global Business Languages. 12: 10. ProQuest 85685222.

- ^ Zuazo 2010

- ^ Zuazo, Koldo (2003). Euskalkiak. Herriaren lekukoak [Dialects. People's witnesses] (in Basque). Elkar. ISBN 9788497830614.

- ^ Corominas, Joan (1960). "La toponymie hispanique prérromane et la survivance du basque jusqu'au bas moyen age" [Pre-Romanesque Hispanic toponymy and the survival of Basque until the late Middle Ages]. IV Congrès International de Sciences Onomastiques (in French).

- ^ Corominas, Joan (1965). Estudis de toponímia catalana, I [Studies of Catalan toponymy, I] (in Catalan). Barcino. pp. 153–217. ISBN 978-84-7226-080-1.

- ^ Corominas, Joan (1972). "De toponimia vasca y vasco-románica en los Bajos Pirineos" [Basque and Basque-Romanesque toponymy in the Low Pyrenees]. Fontes Linguae Vasconum: Studia et Documenta (in Spanish) (12): 299–320. doi:10.35462/flv12.2. ISSN 0046-435X.

- ^ Rohlfs, Gerhard (1980), Le Gascon: études de philologie pyrénéenne. Zeitschrift für Romanische Philologie 85

- ^ Irigoyen, Alfonso (1986). En torno a la toponimia vasca y circumpirenaica [About Basque and circum-Pyrenean toponymy] (in Spanish). Universidad de Deusto.

- ^ Corominas, Joan; Pascual, José A. (1980). "izquierdo". Diccionario crítico etimológico castellano e hispánico (in Spanish) (2.ª reimpresión (marzo de 1989) ed.). Madrid: Gredos. pp. 469–472. ISBN 84-249-1365-5.

- ^ Varela Pose, F.J. (2004)O latín dos canteiros en Cabana de Bergantiños Archived 3 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine. (pdf)Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ Olaetxe, J. Mallea. "The Basques in the Mexican Regions: 16th–20th Centuries." Archived 9 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine Basque Studies Program Newsletter No. 51 (1995).

- ^ Agirrezabal 2003.

- ^ Deen 1937.

- ^ Bakker 1987.

- ^ de Rijk 2008, p. 4.

- ^ de Rijk 2008, p. 17.

- ^ a b c de Rijk 2008, p. 5.

- ^ de Rijk 2008, pp. 7–8.

- ^ de Rijk 2008, pp. 8–9.

- ^ de Rijk 2008, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Trask, R. L. (1997). The History of Basque, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 155–157, ISBN 0-415-13116-2.

- ^ Trask, The History of Basque, pp. 157–163.

- ^ de Rijk 2008, p. 8.

- ^ de Rijk 2008, p. 6.

- ^ de Rijk 2008, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d de Rijk 2008, p. 14.

- ^ a b Hualde, Lujanbio & Zubiri 2010, p. 119.

- ^ Hualde, Lujanbio & Zubiri 2010, p. 113, 119, 121.

- ^ a b de Rijk 2008, p. 15.

- ^ de Rijk 2008, p. 16.

- ^ Hualde, J.I. (1986). "Tone and Stress in Basque: A Preliminary Survey". Anuario del Seminario Julio de Urquijo. XX (3): 867–896. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ Hualde, Jose Ignacio (1991). Basque Phonology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-05655-7.

- ^ "(Basque) INFLECTION §1.4.2.2. Potential paradigms: absolutive and dative".

- ^ Aspecto, tiempo y modo Archived 2 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine in Spanish, Aditzen aspektua, tempusa eta modua in Basque.

- ^ King 1994, p. 393

- ^ Agirre et al. 1992.

- ^ Agirre, E.; Alegria, I.; Arregi, X.; Artola, X.; De Ilarraza, A. Díaz; Maritxalar, M.; Sarasola, K.; Urkia, M. (1992). "XUXEN: A Spelling Checker/Corrector for Basque Based on Two-Level Morphology". Proceedings of the Third Conference on Applied Natural Language Processing. pp. 119–125. doi:10.3115/974499.974520. S2CID 1844637.

- ^ Hualde, José Ignacio; Lakarra, Joseba A.; Trask, R. L. (1 January 1996). Towards a History of the Basque Language. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 978-90-272-8567-6.

- ^ "Basque alphabet" (PDF).

- ^ Lecciones de ortografía del euskera bizkaino, Arana eta Goiri'tar Sabin, Bilbao, Bizkaya'ren Edestija ta Izkerea Pizkundia, 1896 (Sebastián de Amorrortu).

- ^ Aguirre Sorondo Tratado de Molinología – Los Molinos de Guipúzcoa Eusko Ikaskuntza 1988 ISBN 84-86240-66-2

Bibliography

[edit]General and descriptive grammars

[edit]- Allières, Jacques (1979). Manuel pratique de basque. Connaissance des langues (in French). Vol. 13. Paris: A. & J. Picard. ISBN 2-7084-0038-X.

- "Aurkezpena". Sareko Euskal Gramatika (in Basque). Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea.

- de Azkue Aberasturi, Resurrección María (1969). "Morfología vasca". La Gran enciclopedia vasca (in Spanish). Bilbao.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Campion, Arturo (1884). Gramática de los cuatro dialectos literarios de la lengua euskara (in Spanish). Tolosa.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - de Rijk, Rudolf P. G. (2008). Standard Basque: a progressive grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-04242-0. OCLC 636283146.

- Hualde, José Ignacio; Ortiz de Urbina, Jon, eds. (2003). A Grammar of Basque. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017683-1.

- King, Alan R. (1994). The Basque Language: A Practical Introduction. Reno: University of Nevada Press. ISBN 0-87417-155-5.

- Lafitte, Pierre (1962). Grammaire basque – navarro-labourdin littéraire (in French). Donostia/Bayonne: Elkarlanean. ISBN 2-913156-10-X.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) (Dialectal.) - Lafon, René (1972). "Basque". In Haugen, Einar (ed.). Linguistics in Western Europe. Vol. 2: The study of languages. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 1744–1792. doi:10.1515/9783111684970-018. ISBN 9783111684970.

- Tovar, Antonio (1957). The Basque Language. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Uhlenbeck, C. (1947). "La langue basque et la linguistique générale" [The Basque language and general linguistics]. Lingua (in French). 1: 59–76. doi:10.1016/0024-3841(49)90045-5.

- Urquizu Sarasúa, Patricio (2007). Gramática de la lengua vasca (in Spanish). Madrid: UNED. ISBN 978-84-362-3442-8.

- van Eys, Willem J. (1879). Grammaire comparée des dialectes basques (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Linguistic studies

[edit]- Agirre, Eneko, et al. (1992): XUXEN: A spelling checker/corrector for Basque based on two-level morphology.

- Gavel, Henri (1921): Eléments de phonetique basque (= Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos = Revue Internationale des Etudes Basques 12, París. (Study of the dialects.)

- Hualde, José Ignacio (1991): Basque phonology, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-415-05655-7.

- Hualde, José Ignacio; Lujanbio, Oihana; Zubiri, Juan Joxe (2010). "Goizueta Basque" (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 40: 113–127. doi:10.1017/S0025100309990260. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 May 2018.

- Lakarra Andrinua, Joseba A.; Hualde, José Ignacio (eds.) (2006): Studies in Basque and historical linguistics in memory of R. L. Trask – R. L. Trasken oroitzapenetan ikerketak euskalaritzaz eta hizkuntzalaritza historikoaz, (= Anuario del Seminario de Filología Vasca Julio de Urquijo: International journal of Basque linguistics and philology Vol. 40, No. 1–2), San Sebastián.

- Lakarra, J. & Ortiz de Urbina, J.(eds.) (1992): Syntactic Theory and Basque Syntax, Gipuzkoako Foru Aldundia, Donostia-San Sebastian, ISBN 978-84-7907-094-6.

- Orduña Aznar, Eduardo (2005). "Sobre algunos posibles numerales en textos ibéricos". Palaeohispanica. 5: 491–506. This fifth volume of the journal Palaeohispanica consists of Acta Palaeohispanica IX, the proceedings of the ninth conference on Paleohispanic studies.

- de Rijk, R. (1972): Studies in Basque Syntax: Relative clauses PhD Dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts, US.

- Uhlenbeck, C.C. (1909–1910): "Contribution à une phonétique comparative des dialectes basques", Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos = Revue Internationale des Etudes Basques 3 Wayback Machine pp. 465–503 4 Wayback Machine pp. 65–120.

- Zuazo, Koldo (2008): Euskalkiak: euskararen dialektoak. Elkar. ISBN 978-84-9783-626-5.

Lexicons

[edit]- Aulestia, Gorka (1989): Basque–English dictionary University of Nevada Press, Reno, ISBN 0-87417-126-1.

- Aulestia, Gorka & White, Linda (1990): English–Basque dictionary, University of Nevada Press, Reno, ISBN 0-87417-156-3.

- Azkue Aberasturi, Resurrección María de (1905): Diccionario vasco–español–francés, Geuthner, Bilbao/Paris (reprinted many times).

- Michelena, Luis: Diccionario General Vasco/Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia. 16 vols. Real academia de la lengua vasca, Bilbao 1987ff. ISBN 84-271-1493-1.

- Morris, Mikel (1998): "Morris Student Euskara–Ingelesa Basque–English Dictionary", Klaudio Harluxet Fundazioa, Donostia

- Sarasola, Ibon (2010–), "Egungo Euskararen Hiztegia EEH" Egungo Euskararen Hiztegia (EEH) - UPV/EHU, Bilbo: Euskara Institutua Euskara Institutuaren ataria (UPV - EHU), The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU

- Sarasola, Ibon (2010): "Zehazki" Zehazki - UPV/EHU, Bilbo: Euskara Institutua Euskara Institutuaren ataria (UPV - EHU), The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU

- Sota, M. de la, et al., 1976: Diccionario Retana de autoridades de la lengua vasca: con cientos de miles de nuevas voces y acepciones, Antiguas y modernas, Bilbao: La Gran Enciclopedia Vasca. ISBN 84-248-0248-9.

- Van Eys, W. J. 1873. Dictionnaire basque–français. Paris/London: Maisonneuve/Williams & Norgate.

Basque corpora

[edit]- Sarasola, Ibon; Pello Salaburu, Josu Landa (2011): "ETC: Egungo Testuen Corpusa" Egungo Testuen Corpusa (ETC) - UPV/EHU, Bilbo: Euskara Institutua Euskara Institutuaren ataria (UPV - EHU), The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU University of the Basque Country

- Sarasola, Ibon; Pello Salaburu, Josu Landa (2009): "Ereduzko Prosa Gaur, EPG" Ereduzko Prosa Gaur (EPG) - UPV/EHU, Bilbo: Euskara Institutua Euskara Institutuaren ataria (UPV - EHU), The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU University of the Basque Country

- Sarasola, Ibon; Pello Salaburu, Josu Landa (2009–): "Ereduzko Prosa Dinamikoa, EPD" Ereduzko Prosa Dinamikoa (EPD) - UPV/EHU, Bilbo: Euskara Institutua Euskara Institutuaren ataria (UPV - EHU), The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU University of the Basque Country

- Sarasola, Ibon; Pello Salaburu, Josu Landa (2013): "Euskal Klasikoen Corpusa, EKC" Euskal Klasikoen Corpusa (EKC) - UPV/EHU, Bilbo: Euskara Institutua Euskara Institutuaren ataria (UPV - EHU), The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU University of the Basque Country

- Sarasola, Ibon; Pello Salaburu, Josu Landa (2014): "Goenkale Corpusa" Goenkale Corpusa - UPV/EHU, Bilbo: Euskara Institutua Euskara Institutuaren ataria (UPV - EHU), The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU University of the Basque Country

- Sarasola, Ibon; Pello Salaburu, Josu Landa (2010): "Pentsamenduaren Klasikoak Corpusa" Pentsamenduaren Klasikoak Corpusa - UPV/EHU, Bilbo: Euskara Institutua Euskara Institutuaren ataria (UPV - EHU), The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU University of the Basque Country

Other

[edit]- Agirre Sorondo, Antxon. 1988. Tratado de Molinología: Los molinos en Guipúzcoa. San Sebastián: Eusko Ikaskunza-Sociedad de Estudios Vascos. Fundación Miguel de Barandiarán.

- Bakker, Peter (1987). "A Basque Nautical Pidgin: A Missing Link in the History of Fu". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 2 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1075/jpcl.2.1.02bak.

- Bakker, Peter, et al. 1991. Basque pidgins in Iceland and Canada. Anejos del Anuario del Seminario de Filología Vasca "Julio de Urquijo", XXIII.

- Deen, Nicolaas Gerard Hendrik. 1937. Glossaria duo vasco-islandica. Amsterdam. Reprinted 1991 in Anuario del Seminario de Filología Vasca Julio de Urquijo, 25(2):321–426.

- Hualde, José Ignacio (1984). "Icelandic Basque pidgin". Journal of Basque Studies in America. 5: 41–59.

History of the language and etymologies

[edit]- Agirrezabal, Lore (2003). Erromintxela, euskal ijitoen hizkera [Rommintxela, the language of the Basque gypsies] (in Basque). San Sebastián: Argia.

- Azurmendi, Joxe: "Die Bedeutung der Sprache in Renaissance und Reformation und die Entstehung der baskischen Literatur im religiösen und politischen Konfliktgebiet zwischen Spanien und Frankreich" In: Wolfgang W. Moelleken (Herausgeber), Peter J. Weber (Herausgeber): Neue Forschungsarbeiten zur Kontaktlinguistik, Bonn: Dümmler, 1997. ISBN 978-3537864192

- Hualde, José Ignacio; Lakarra, Joseba A. & R.L. Trask (eds) (1996): Towards a History of the Basque Language, "Current Issues in Linguistic Theory" 131, John Benjamin Publishing Company, Amsterdam, ISBN 978-1-55619-585-3.

- Michelena, Luis, 1990. Fonética histórica vasca. Bilbao. ISBN 84-7907-016-1

- Lafon, René (1944): Le système du verbe basque au XVIe siècle, Delmas, Bordeaux.

- Löpelmann, Martin (1968): Etymologisches Wörterbuch der baskischen Sprache. Dialekte von Labourd, Nieder-Navarra und La Soule. 2 Bde. de Gruyter, Berlin (non-standard etymologies; idiosyncratic).

- Orpustan, J. B. (1999): La langue basque au Moyen-Age. Baïgorri, ISBN 2-909262-22-7.

- Pagola, Rosa Miren. 1984. Euskalkiz Euskalki. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpe.

- Rohlfs, Gerhard. 1980. Le Gascon: études de philologie pyrénéenne. Zeitschrift für Romanische Philologie 85.

- Trask, R.L.: History of Basque. New York/London: Routledge, 1996. ISBN 0-415-13116-2.

- Trask, R.L. † (edited by Max W. Wheeler) (2008): Etymological Dictionary of Basque, University of Sussex (unfinished). Also "Some Important Basque Words (And a Bit of Culture)" Buber's Basque Page: The Larry Trask Archive: Some Important Basque Words (And a Bit of Culture)

- Zuazo, Koldo (2010). El euskera y sus dialectos. Zarautz (Gipuzkoa): Alberdania. ISBN 978-84-9868-202-1.

Relationship to other languages

[edit]Proto-Indo-European

[edit]- Blevins, Juliette (2018). "Advances in Proto-Basque Reconstruction with Evidence for the Proto-Indo-European-Euskarian Hypothesis". Routledge & CRC Press. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

General reviews of the theories

[edit]- Jacobsen, William H. Jr. (1999). "Basque Language Origin Theories". In Douglass, William A.; Urza, Carmelo; White, Linda; Zulaika, Joseba (eds.). Basque Cultural Studies. Basque Studies Program Occasional Papers Series. Vol. 5. Reno: Basque Studies Program, University of Nevada. pp. 27–43. ISBN 9781877802034. OCLC 42619655.

- Lakarra Andrinua, Joseba (1998). "Hizkuntzalaritza konparatua eta aitzineuskararen erroa" (PDF). Uztaro (in Basque). 25: 47–110. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. (includes review of older theories).

- Lakarra Andrinua, Joseba (1999). "Ná-De-Ná" (PDF). Uztaro (in Basque). 31: 15–84. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011.

- Trask, R. L. (1995). "Origin and Relatives of the Basque Language: Review of the Evidence". In Hualde, J.; Lakarra, J.; Trask, R. L. (eds.). Towards a History of the Basque Language. John Benjamins.

- Trask, R. L. (1996). History of Basque. London: Routledge. pp. 358–414. ISBN 0-415-13116-2.

Afroasiatic hypothesis

[edit]- Schuchardt, Hugo (1913): "Baskisch-Hamitische wortvergleichungen" Revista Internacional de Estudios Vascos = "Revue Internationale des Etudes Basques" 7:289–340.

- Mukarovsky, Hans Guenter (1964/66): "Les rapports du basque et du berbère", Comptes rendus du GLECS (Groupe Linguistique d'Etudes Chamito-Sémitiques) 10:177–184.

- Mukarovsky, Hans Guenter (1972). "El vascuense y el bereber". Euskera. 17: 5–48.

- Trombetti, Alfredo (1925): Le origini della lingua basca, Bologna, (new edit ISBN 978-88-271-0062-2).

Dené–Caucasian hypothesis

[edit]- Bengtson, John D. (1999): The Comparison of Basque and North Caucasian. in: Mother Tongue. Journal of the Association for the Study of Language in Prehistory. Gloucester, Mass.

- Bengtson, John D (2003). "Notes on Basque Comparative Phonology" (PDF). Mother Tongue. VIII: 23–39.

- Bengtson, John D. (2004): "Some features of Dene–Caucasian phonology (with special reference to Basque)." Cahiers de l'Institut de Linguistique de Louvain (CILL) 30.4, pp. 33–54.

- Bengtson, John D.. (2006): "Materials for a Comparative Grammar of the Dene–Caucasian (Sino-Caucasian) Languages." (there is also a preliminary draft)

- Bengtson, John D. (1997): Review of "The History of Basque". London: Routledge, 1997. Pp.xxii,458" by R.L. Trask.

- Bengtson, John D., (1996): "A Final (?) Response to the Basque Debate in Mother Tongue 1."

- Trask, R.L. (1995). "Basque and Dene–Caucasian: A Critique from the Basque Side". Mother Tongue. 1: 3–82.

Caucasian hypothesis