Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Battle of Chaeronea (86 BC)

View on Wikipedia| Battle of Chaeronea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Mithridatic War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Republic | Kingdom of Pontus | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Archelaus Taxiles (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 30,000 men[1][2] |

60,000 men 90 scythed chariots | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 12 killed, according to Sulla (greatly disputed) | All but 10,000, according to Plutarch[3] (disputed) | ||||||

Location within Greece | |||||||

The Battle of Chaeronea was fought by the Roman forces of Lucius Cornelius Sulla and Mithridates' general, Archelaus, near Chaeronea, in Boeotia, in 86 BC during the First Mithridatic War. The battle ended with a complete rout of the Pontic army and a decisive victory for the Romans.

Forces

[edit]

Pontic troops

[edit]One of Mithridates generals, Taxiles, and a large force were sent to join up with Archelaus and his forces in the Elatean plains.[4][5] Baker cites a Roman army of less than 17,000, excluding allied troops, and the enemy Pontic army outnumbering those troops 5 to 1, or around 85,000 troops.[6] Delbruck presents both a "supposed" figure of 120,000 troops and a reduced figure of a "more modest" 60,000 Asiatics.[1] Delbruck further makes comments on the available primary sources and specifically refers to "vague and boastful" memoirs of Sulla which were the primary source that other historians of the time used, such as Plutarch.[1] Hammond preferred the figure of 60,000 soldiers, which is supplied by Memnon of Heraclea.[7] The Pontic forces are also said to have had 90 scythed chariots.[8]

Mithridates' armies were a compound make-up of Greek and Oriental elements, the infantry was made up of Macedonian style phalanxes, with Pontic phalangists for missile units, and the cavalry a combination of horse and scythe-wheeled chariots.[9]

Sulla's troops

[edit]Sulla's forces are approximated to have been around 30,000 men,[1][2] with Baker commenting that of these less than 17,000 were Romans and the rest were composed of Macedonian and Greek allies.[10] Baker, however, doesn't give a concrete value for the number of Macedonian and Greek soldiers involved in the battle, merely noting a disparity of "over three to one" between the Roman and Pontic troops once the allies are accounted for.[10] The Roman forces were composed of veteran Roman legions and some cavalry.[2][11]

Geography

[edit]Sulla advanced his army from Athens and into Boeotia, where he met up with Hortensius, who had advanced southward from Thessaly, at Philoboetus.[4][5] Hortensius himself had moved through the mountains with a guide, intent on avoiding an ambush.[4][5] Baker remarks that this movement put Sulla in a favourable position, his supplies were secure, wood and water were plentiful, the roads into Thessaly could be watched and guarded with ease, and the hills provided an advantage.[4][5] Baker describes this position as "commanding the Elatean plain and the valley of Cephisus."[4] Sulla was determined to dictate the time and place of the battle.[10]

Taxiles and his large force had to go north through a defile, before turning into the narrower valley, between Orchomenos and Chaeronea to meet up with Archelaus and his forces.[4][5] The consequence of this was that once Taxiles and his forces arrived, it became impossible for the forces to retreat and instead had to stand and fight.[4] This force was encamped in the valley in a position which allowed the commanders to watch the Roman army.[10] Archelaus intended to pursue a war of attrition, Taxiles with his far larger force, however, was determined to defeat the Romans in battle and insisted on an engagement and, given the circumstances, Archelaus was in no position to refuse.[12]

Prelude

[edit]The Pontic forces, encamped in the valley, sent out numerous foraging parties which plundered and burned the countryside.[4][5] Sulla was unable to defend the region with his far smaller force and instead was forced to stay camped up on the hill.[4][5] Instead of remaining idle, Sulla ordered his men to dig entrenchments on the flanks to protect against possible envelopment by cavalry and also ordered the construction of palisades in the front to defend against the chariots.[13] The exercise was twofold in intention, first Sulla sought to ensure the discipline of his soldiers and second, he hoped to tire the soldiers out so that they were more willing to battle.[9][14] When his troops came to him requesting battle, Sulla challenged the men, citing that their new found will to fight was a response to inherent laziness to work, to occupy the hill of Parapotamii.[14] The men agreed to this task, Archelaus had already marked the position for his own men and it became a race between Archelaus' and Sulla's men to occupy the position first.[14] Baker describes this position as "almost impregnable", the occupier had no choice but to turn eastward towards Chaeronea to advance and if action took place here, one army or the other would be fighting at an angle.[14]

Order of battle

[edit]For Rome, Sulla was in command of the right flank of the Roman army, the legate Murena on the left, Hortensius and Galba commanded the reserve cohorts in the rear with Hortensius on the left and Galba on the right.[5][11] Finally, Gabinius and one full legion were sent to occupy the town of Chaeronea itself.[11] For Mithridates, Archelaus was in command.[11]

Battle

[edit]Sulla opened the engagement with an apparent retreat, leaving one unit under Gabinius to occupy and defend the town of Chaeronea and having Murena retreat back onto Mount Thurium, while he himself marched alongside the right bank of the river Cephisus.[11] Archelaus in response marched forth to occupy a position facing Chaeronea and extended a flanking force to occupy Murena's troops at Thurium.[11] Sulla linked up with Chaeronea and extended the Roman line across the valley.[11] Murena's position was the weakest, possibly untenable, so to strengthen it Gabinius recruited some of the locals to help deal with the danger, a proposition which Sulla approved.[11] By this point, Sulla had taken up his position on the right and the battle began.[15]

Murena, assisted by the force of natives from Chaeronea, cautiously launched an attack against the right flank, which, being attacked from above, was forced down the hill with disastrous consequences and possibly up to 3,000 casualties.[5][16] In exchange, the Pontic chariots charged forth against Gabinius in the centre, who withdrew his troops behind the defensive stakes he had prepared, which stymied the chariots.[16] The barrage of Roman javelins and arrows then brought down many of the chariots and caused the rest to retreat in panic. Many of the survivors crashed into the phalanx advancing behind them, leaving it vulnerable to attack.[13]

The Roman legions then came out of their entrenchment to face the Pontic phalanx of freed slaves, who were prevented from coming to a full charge by the field fortifications the Romans had in place.[17] The legionaries, indignant at having to fight against slaves instead of free men, fought with a terrible fury. They parried the enemy's long pikes with their short swords and shields and in some cases simply grappled them away with their bare hands.[17] In the end the barrage of stones and bolts from the Roman catapults so disordered the phalanx that the Roman swordsmen were able to infiltrate the hedge of pikes and rout it.[18]

In the meantime, Archelaus continued extending his line rightward to outflank Murena on the Roman left wing.[19][20] Hortensius, with the reserve cohorts under his command, came to Murena's rescue, but Archelaus, with 2,000 cavalry, promptly wheeled and pushed him back to the foothills, whence Hortensius's force stood isolated and in danger of being annihilated.[19][21] Seeing this, Sulla raced across the field with his cavalry from the Roman right which was not yet engaged, forcing Archelaus to withdraw.[19][21] The Pontic commander now took the opportunity to ride against the weakened Roman right, left vulnerable by Sulla's absence, and at the same time left Taxiles with the bronze-shields to continue the attack on Murena, who was now exposed due to the retreat of Hortensius.[19]

Sending Hortensius with 4 cohorts to reinforce Murena, Sulla quickly returned to the right with his cavalry, bringing also one cohort from Hortensius' force and another two from (presumably) the other reserve under Galba.[19] The Romans there were resisting well, and when Sulla arrived they broke through the Pontic line and pursued them towards the Cephissus river and Mount Akontion.[21][22] The centre began advancing forward being led by Gabinius who was slaughtering the enemy troops.[18] Seeing that Murena on the opposite wing was also successful, Sulla ordered a general advance. The entire Pontic army routed, and the commander Taxiles fell into Roman hands, while Archelaus escaped with what remained of his force to Chalcis.[21] It was said that only 10,000 Pontic soldiers were able to save themselves, and although this is probably an exaggeration, their losses were nonetheless substantial.[23] Sulla reported that 100,000 of Archelaus' troops were killed, that 14 of his own were missing at the end of the battle and that two of those made it back by the next day.[9] These figures are, however, called into question as being wholly unconvincing.[1][9] Despite the odds, however, the Romans had emerged victorious.[24]

Aftermath

[edit]

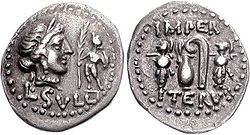

In the immediate aftermath of the battle Sulla erected two trophies: one on the plain near the Molos, where Archelaus' forces had been routed, and the other on Mount Thurium to commemorate Homoloichus and Anaxidamus' dislodgement of the Pontic garrison there. These trophies are mentioned by Plutarch and Pausanias,[26][27] and seem to be depicted on coinage issued by Sulla after the battle.[25] Several fragments from the Thurium trophy were uncovered on Isoma Hill by archaeologists in 1990. It was a square base of whitish-gray marble with a double rebate at the bottom and a torus moulding on top, which supported an unfluted column, which would probably have culminated in a stone sculpture of a panoply (this was not found, but is indicated by parallels, depictions of a pair of trophies on Athenian coinage minted after the battle, and one has been found from this period at Orchomenus). An irregularly-spaced inscription on the front of the base reads:

Ὁμολώιχος

Ϝανα[ξ]ίδαμος

ἀρ[ισ]τίς

Homoloichus,

Anaxidamus:

heroes.

Plutarch, who came from Chaeronea, reports that the trophy was also inscribed with Sulla's name and the names of the gods Ares, Nike, and Aphrodite (= Mars, Victoria, and Venus), but this inscription does not survive.[29]

After the battle, Archelaeus fled to the island of Euboea and immediately started using the fleet stationed there to harass his opponents naval traffic and sending raids against the Romans and their allies.[30] When Sulla arrived at Thebes he held victory games, during which he may have been made aware of the approach of Lucius Valerius Flaccus who had recently landed in Epirus.[5][24] Flaccus and Sulla met at Melitaea in Thessaly, though neither army made a move, both armies set up camp and waited for the other to attack.[31] No attack came, and after some time Flaccus' soldiers began to desert in favour of Sulla, at first slowly but with time in increasing numbers, eventually Flaccus had to break camp or lose his entire army.[31] Meanwhile, Archelaeus, who had wintered on the Island of Euboea, was reinforced by 80,000 men brought over from Asia Minor by Dorylaeus, another of Mithridates' generals. The Mithridatic army then embarked and sailed to Chalcis from where they marched back into Boeotia.[5][9][31] Both Sulla and Flaccus were aware of these developments, so, rather than waste Roman troops to fight each other, Flaccus took his soldiers and headed for Asia Minor while Sulla turned back to face Archelaus once again.[32] Sulla moved his army a few miles to the east of Chaeronea and into position near Orchomenos, a place he chose for its natural entrenchment.[32] Here, Sulla once more, and once again outnumbered, faced off against Archelaus at the Battle of Orchomenus.[13]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Delbruck, Hans (1990). Warfare in Antiquity. University of Nebraska Press. p. 438. ISBN 0-8032-9199-X.

- ^ a b c Eggenberger, David (2012). An Encyclopaedia of Battles: Accounts of Over 1,560 Battles from 1479 BC to the Present. Courier Corporation. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-486-14201-2.

- ^ Plutarch Life of Sulla 19.4

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. p. 198. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Venning, Timothy (2011). A Chronology of the Roman Empire. A&C Black. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-4411-5478-1.

- ^ Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. pp. 199–200. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- ^ Hammond, p. 199.

- ^ Plutarch Life of Sulla 15

- ^ a b c d e Warry, John (2015). Warfare in the Classical World: War and the Ancient Civilizations of Greece and Rome. Pavilion Books. ISBN 978-1-84994-315-4.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. p. 199. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. pp. 200–201. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- ^ Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. pp. 198–199. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- ^ a b c Tucker, Spencer (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- ^ a b c d Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. p. 200. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- ^ Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. pp. 201–202. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- ^ a b Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. p. 202. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- ^ a b Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. pp. 202–203. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- ^ a b Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. p. 203. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- ^ a b c d e Hammond, p. 194.

- ^ Keaveney, p. 78.

- ^ a b c d Keaveney, p. 80.

- ^ Hammond, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Hammond, p. 195.

- ^ a b Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. p. 204. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- ^ a b Camp, John; Ierardi, Michael; McInerney, Jeremy; Morgan, Kathryn; Umholtz, Gretchen (1992). "A Trophy from the Battle of Chaironeia of 86 B. C.". American Journal of Archaeology. 96 (3): 449=450. doi:10.2307/506067. ISSN 0002-9114.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Sulla 19.9-10; Pausanias 9.40.7

- ^ Camp, John; Ierardi, Michael; McInerney, Jeremy; Morgan, Kathryn; Umholtz, Gretchen (1992). "A Trophy from the Battle of Chaironeia of 86 B. C.". American Journal of Archaeology. 96 (3): 443. doi:10.2307/506067. ISSN 0002-9114.

- ^ Camp, John; Ierardi, Michael; McInerney, Jeremy; Morgan, Kathryn; Umholtz, Gretchen (1992). "A Trophy from the Battle of Chaironeia of 86 B. C.". American Journal of Archaeology. 96 (3): 445. doi:10.2307/506067. ISSN 0002-9114.

- ^ Camp, John; Ierardi, Michael; McInerney, Jeremy; Morgan, Kathryn; Umholtz, Gretchen (1992). "A Trophy from the Battle of Chaironeia of 86 B. C.". American Journal of Archaeology. 96 (3): 444–449. doi:10.2307/506067. ISSN 0002-9114.

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Mithridates the Great: Rome's Indomitable Enemy, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. p. 218. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- ^ a b Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. p. 219. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

References

[edit]- Baker, George (2001). Sulla the Fortunate: Roman General and Dictator. Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 1-4617-4168-8.

- Delbrück, Hans (1975) [1900]. History of the Art of War volume 1: Warfare in Antiquity. Translated by Walter J. Renfroe Jr. (3rd ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6584-0.

- Eggenberger, David (2012). An Encyclopedia of Battles. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-14201-2.

- Hammond, N.G.L. (1938). "The two battles of Chaeronea (338 B.C. and 86 B.C.)". Klio. 31: 186–218. doi:10.1524/klio.1938.31.jg.186.

- Keaveney, Arthur (2005) [1982]. Sulla: The Last Republican (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-33660-0.

- Tucker, Spencer (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- Venning, Timothy (2011). A Chronology of the Roman Empire. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4411-5478-1.

- Warry, John (2015). Warfare in the Classical World: War and the Ancient Civilizations of Greece and Rome. Pavilion Books. ISBN 978-1-84994-315-4.[permanent dead link]

Battle of Chaeronea (86 BC)

View on GrokipediaHistorical Context

Origins of the First Mithridatic War

The First Mithridatic War arose from Mithridates VI of Pontus's expansionist ambitions in Asia Minor, which directly challenged Roman influence over client kingdoms such as Bithynia and Cappadocia. Mithridates, who had ascended the throne around 120 BC, systematically consolidated power by conquering territories along the Black Sea and interfering in neighboring dynasties, including the assassination of Cappadocian kings Ariarathes VI and VII to install his own son as ruler. Roman interventions, beginning around 95 BC, repeatedly restored Ariobarzanes I to the Cappadocian throne after Mithridates or his agents expelled him, establishing a pattern of friction over regional control. These early clashes highlighted Mithridates's resistance to Roman meddling, as he viewed Pontus's Hellenistic kingdom as a counterweight to Roman dominance in the East.[5] The immediate trigger occurred in 90 BC, when Manius Aquillius, the Roman proconsul in Asia, authorized Nicomedes IV of Bithynia—a Roman ally burdened by debts to Roman tax collectors—to invade Pontus under the pretext of debt recovery, though Aquillius's motives included personal ambition for military command. Nicomedes's forces were decisively defeated by Mithridates near the Amnias River, providing the Pontic king with justification for retaliation. Exploiting Rome's distraction during the Social War (91–88 BC), which tied down Roman legions against Italian allies, Mithridates annexed Paphlagonia in 89 BC after its inhabitants appealed to him against Bithynian aggression, then overran Bithynia following Nicomedes's flight to Rome, and reoccupied Cappadocia for the fourth time, deposing Ariobarzanes once more. Aquillius attempted to rally resistance but failed, leading to the collapse of Roman authority in the region.[6][7] By late 89 BC, Mithridates's armies had advanced into Phrygia, Mysia, Lydia, and the Roman province of Asia itself, where cities largely surrendered without prolonged resistance due to his promises of tax relief and anti-Roman propaganda. In spring 88 BC, to consolidate control and eliminate potential fifth columnists, Mithridates issued an edict ordering the extermination of all Romans and Italians in Asia Minor; local rulers and mobs complied, resulting in the deaths of approximately 80,000 to 150,000 individuals in what became known as the Asiatic Vespers. This massacre, combined with Mithridates's dispatch of general Archelaus to seize Athens and other Greek cities—which revolted against Roman garrisons—prompted the Roman Senate to declare war on Pontus in 88 BC, marking the formal onset of the conflict despite ongoing internal Roman divisions.[6][5]Sulla's Eastern Campaign

Lucius Cornelius Sulla departed Italy in early 87 BC after securing his Eastern command through the march on Rome the previous year, crossing the Adriatic to land at Dyrrachium in Illyria with his legions.[8] From there, he advanced southward into Greece, where most cities submitted except Athens, governed by the pro-Mithridatic tyrant Aristion, who had aligned the city with King Mithridates VI Eupator of Pontus.[9] Sulla arrived near Athens in late 87 BC and promptly encircled both the city and its vital port at Piraeus with a double line of fortifications to sever supply lines, while constructing massive siege engines that demanded vast resources, including timber stripped from sacred groves like the Academy and Lyceum.[9] Archelaus, Mithridates' commander in Greece, attempted to relieve the besieged cities by sea but could not fully dislodge Sulla's blockade despite naval superiority.[8] The campaign unfolded amid a severe winter, taxing Sulla's forces with shortages, yet he pressed on by seizing treasures from sanctuaries at Epidaurus, Olympia, and Delphi to fund operations.[9] On the Calends of March (March 1), 86 BC, Roman sappers undermined and breached the Heptachalcum section of Athens' walls, allowing troops to storm the city in a ferocious assault that ended with its capture and a sack characterized by widespread killing, with blood reportedly flowing through the Cerameicus and marketplace.[9] [8] Piraeus fell soon after, its dockyards and Philon's arsenal put to the torch by Sulla's orders.[9] Aristion fled to the Acropolis, where he surrendered and faced execution.[8] With Attica secured but provisions scarce, Sulla shifted operations to Boeotia in spring 86 BC to confront Archelaus' primary Pontic army, estimated at 100,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry, and 90 scythed chariots, against Sulla's outnumbered force of under 15,000 foot and 1,500 horse.[9] This maneuver directly led to the pitched engagement at Chaeronea, where Sulla's tactical acumen would prove decisive.[9]Opposing Forces

Composition of Sulla's Roman Army

Sulla's army at the Battle of Chaeronea consisted primarily of five veteran Roman legions, augmented by a small number of auxiliary cohorts and cavalry units. According to Appian, these forces arrived in Greece in 87 BC, comprising the core of Sulla's expeditionary army against Mithridates VI's forces.[10] Each legion numbered approximately 5,000 heavy infantry organized in cohorts, equipped with pila, gladii, and large shields, reflecting the post-Marian professional structure emphasizing disciplined manipular tactics adapted to cohort deployments.[10] These legions were battle-hardened troops drawn from Sulla's earlier commands, including veterans of the Social War, instilling high morale and tactical cohesion crucial for facing numerically superior foes.[11] Auxiliary cohorts provided additional infantry support, likely including lighter-armed troops for flexibility, though specifics on their ethnic composition—possibly including Thracians or local levies—are not detailed in primary accounts.[10] Cavalry elements, described as a contingent accompanying the legions, were positioned on the flanks during the engagement, enabling flanking maneuvers that exploited gaps in the Pontic lines.[10] Plutarch records Sulla's dispatch claiming fewer than 15,000 infantry and 1,500 cavalry to emphasize the victory's decisiveness, but this figure is widely regarded as understated for propagandistic effect, with Appian's account implying a total force under 40,000 against Archelaus' much larger host.[9] Some Greek defectors bolstered the ranks, contributing to the Roman order's resilience.[11]Composition of Archelaus' Pontic Army

Archelaus commanded a multinational force of approximately 120,000 troops at the Battle of Chaeronea, drawn from Mithridates VI's expansive empire spanning the Black Sea region and Anatolia.[10] This figure, reported by the Roman historian Appian, reflects the king's mobilization of diverse subject peoples, though ancient army sizes are often subject to exaggeration for dramatic effect.[12] The army's composition was ethnically heterogeneous, comprising Thracians, Pontics, Scythians, Cappadocians, Bithynians, Galatians, and Phrygians, as detailed by Appian.[12] Pontic troops formed the core heavy infantry, likely arrayed in a Macedonian phalanx formation emulating Hellenistic traditions, given Archelaus's background as a Macedonian exile and Mithridates' adoption of such tactics. Light infantry and skirmishers from Asian provinces provided flexibility, while Scythian and Thracian elements contributed cavalry and missile troops suited to open terrain.[10] Supporting arms included scythed chariots, a signature of Eastern armies that Appian notes were deployed in the initial assault, though their effectiveness was limited against Roman entrenchments.[12] The reliance on levied auxiliaries from varied cultures introduced challenges in cohesion and discipline compared to the professional Roman legions, contributing to vulnerabilities in sustained combat. Primary accounts like Appian's, written centuries after the event, prioritize narrative over precise logistics, underscoring the need for cautious interpretation of troop quality and organization.[10]Strategic Prelude

Geographical Setting

The Battle of Chaeronea occurred near the town of Chaeronea in Boeotia, a region in central Greece, situated on the southern banks of the Cephisus River.[11] The battlefield encompassed a narrow plain, approximately 1-2 miles wide south of the river, which widened to the north and became marshy toward the south.[11] This plain was bordered by hills and mountains, including Mount Thurium to the south (rising about 500 meters), Mount Acontium north of the river, and Mount Hedylium further north, with additional elevations such as Petrachos to the east and Thourion to the west.[11][13] The Cephisus River flowed westward across the plain, dividing the opposing forces and influencing their deployments, while the surrounding rocky terrain and steep hills restricted maneuverability, particularly for cavalry and chariots.[2][11] Archelaus positioned the Pontic army in a secure but uneven, rocky area near Chaeronea, hemmed in by steep rocks that offered little room for retreat if defeated.[12] In response, Sulla seized the adjacent broad plain, establishing a more favorable position on higher ground including the hill of Philoboeotus, which allowed defensive preparations such as ditches to counter Pontic cavalry threats.[12][2] Strategically, the geography controlled key passes, such as the Acropolis of Parapotamii along the Cephisus, vital for Roman supply lines from Attica northward.[11] The narrow valley between Mounts Acontium and Hedylium further channeled Pontic movements, while the overall terrain favored Sulla's legionary infantry over the larger but less cohesive Pontic forces, enabling effective flanking and pursuit.[11][14]