Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

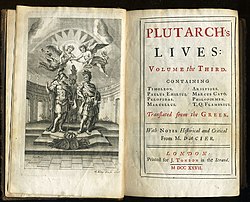

Parallel Lives

View on Wikipedia

The Parallel Lives (Ancient Greek: Βίοι Παράλληλοι, Bíoi Parállēloi; Latin: Vītae Parallēlae) is a series of 48 biographies of famous men written in Greek by the Greco-Roman philosopher, historian, and Apollonian priest Plutarch, probably at the beginning of the second century. The lives are arranged in pairs to illuminate their common moral virtues or failings.[1]

Key Information

The surviving Parallel Lives comprises 23 pairs of biographies, each pair consisting of one Greek and one Roman of similar destiny, such as Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, or Demosthenes and Cicero. There are also four singular Lives, recounting the stories of Artaxerxes, Aratus, Galba, and Otho. Traces of other biographies point to an additional twelve single Lives that are now missing.[2]

It is a work of considerable importance, not only as a source of information about the individuals described, but also about the times in which they lived.

Motivation

[edit]Parallel Lives was Plutarch's second set of biographical works, following the Lives of the Roman Emperors from Augustus to Vitellius. Of these, only the Lives of Galba and Otho survive.[3][4]

As he explains in the first paragraph of his Life of Alexander, Plutarch's interest was primarily ethical rather than historical ("For it is not Histories that I am writing, but Lives"). He was concerned with exploring the influence of character, good or bad, on the lives and destinies of famous men. He wished to shed light on the actions and achievements of the Greek men of the distant past through his comparisons with the more recent past of Rome.[5] George Wyndham's introduction in the 1895 publication of the Lives writes of:

[Plutarch's] desire, as a man, to draw the noble Grecians, long since dead, a little nearer to the noonday of the living...By placing them side by side, he gave back to the Greeks that touch which they had lost with the living in the death of Greece, and to the Romans that distinction from everyday life which they were fast beginning to lose.[6]

Because the men he wrote about had been dead nearly 300 years before Plutarch's time, his writing was largely based on manuscripts of uncertain accuracy.[7] Plutarch himself had little faith in the historic truth found in resources from the past. In his life of Pericles, he states:

It is so hard to find out the truth of anything by looking at the record of the past. The process of time obscures the truth of former times, and even contemporaneous writers disguise and twist the truth out of malice or flattery.[7]

Translations

[edit]

The Lives were circulated enough throughout Rome after their original production that they survived the Dark Ages. However, many of the Lives which appear in a list of his writings have not been found. Among these are his biography of Hercules and his comparison of Epaminondas of Greece and Scipio Africanus of Rome.[7]

The first printed edition of his Parallel Lives appeared in Rome around 1470, translated into Latin from the original Greek. Several more translations would appear through the end of the fifteenth century, with an Italian translation in 1482 then in Spanish in 1491. A German translation would be written in 1541.[8]

The Lives would gain massive popularity after the 1559 French translation by Amyot, the Abbot of Bellozane. This reproduction of the work was an immediate success. Six authorized editions were published by the Parisian house of Vascosan by the end of 1579, and it was largely pirated.[9]

Amyot's translation served as a direct source for Thomas North's 1579 English translation, which phrase for phrase follows Amyot's French version.[9] This rendition would become an important source-material for Shakespeare's Coriolanus, Julius Caesar, and Antony and Cleopatra.[2]

In 1683 a new English edition of the Lives was published, this time translated from the original Greek, unlike North's translation. This translation has come to be known as "Dryden's translation", despite the poet John Dryden only serving as the project's editor and ultimately having no role in the actual translation of the work. It was published by Jacob Tonson.[10]

Content

[edit]Plutarch structured Parallel Lives by pairing lives of famous Greeks with those of famous Romans. Eighteen of these close with a formal comparison between its characters.[2]

Plutarch's focus within the Lives is to create a neat depiction of character that fits into his comparison to the parallel life. Historical context is neglected in favor of moral analysis in order to create his desired anecdote. This can be seen in his deviation from the sources he used to understand the characters he represented: "His Eumenes is a far cry from any picture of Eumenes he can have found in the historical literature he used. It is an artificial creation to provide a counterpart to his Sertorius and can only be understood against the background of the Sertorius."[11] The Parallel Lives, therefore, need to be understood primarily as literary biographies, not as histories.

Within the biographies Plutarch presents both the positive and negative attributes of each character. Rather than speaking of the character’s lives in simple terms surrounding the events of their lives, he describes the moral and psychological motivations behind each figure. He uses them as ‘moral actors’, prompting self-examination and self-improvement from the reader. Even when making judgements on the characters within the text, Plutarch still “poses questions to his readers and suggests alternative trains of thought that might be possible for them to follow”.[12] This encourages the reader to acknowledge and appreciate contradicting viewpoints and broaden their moral perspectives.

The table below gives the list of the biographies. Its order follows the one found in the Lamprias Catalogue, the list of Plutarch's works made by his hypothetical son Lamprias.[13] The table also features links to several English translations of Plutarch's Lives available online. While the four unpaired biographies are not considered to be parts of the Parallel Lives, they can be included in the term Plutarch's Lives.

All dates are BC.

| № | Greek | Roman | Comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life | Years | Translations | Life | Years | Translations | ||

| 1 | Theseus | mythic | D G L P LV | Romulus | fl. 771–717 | D G L | D G L |

| 2 | Lycurgus | fl. c. 820 | (D) G L | Numa Pompilius | 715–673 | D G L | D G L |

| 3 | Themistocles | c. 524–459 | D G L P | Camillus | 446–365 | (D) G L | n/a |

| 4 | Solon | 638–558 | D G L P | Poplicola | d. 503 | D G L | D G L |

| 5 | Pericles | c. 495–429 | (D) G L P | Fabius Maximus | 275–203 | D G L | D G L |

| 6 | Alcibiades | 450–404 | (D) G L P | Coriolanus | fl. 475 | (D) G L P | D G L |

| 7 | Epaminondas | d. 362 | Lost | Scipio Africanus or Aemilianus[14] | 236–183 or 185–129 | Lost | |

| 8 | Phocion | c. 402 – c. 318 | D G L P | Cato the Younger | 95–46 | (D) G L | n/a |

| 9–10 | Agis | fl. 245 | D L | Tiberius Gracchus | c. 164–133 | D L | D L |

| Cleomenes | d. 219 | D L | Gaius Gracchus | 154–121 | D L | ||

| 11 | Timoleon | c. 411–337 | (D) G L | Aemilius Paullus | c. 229–160 | (D) G L | D G L |

| 12 | Eumenes | c. 362–316 | D G L | Sertorius | c. 123–72 | D G L | D G L |

| 13 | Aristides | 530–468 | D G L P | Cato the Elder | 234–149 | D G L | G L |

| 14 | Pelopidas | d. 364 | D G L | Marcellus | 268–208 | D G L | D G L |

| 15 | Lysander | d. 395 | D G L P | Sulla | 138–78 | (D) G L | D G L |

| 16 | Pyrrhus | 319/318–272 | (D) G L | Marius | 157–86 | (D) G L | n/a |

| 17 | Philopoemen | 253–183 | D G L | Titus Flamininus | c. 229–174 | D G L | D G L |

| 18 | Nicias | 470–413 | D G L P | Crassus | c. 115–53 | (D) G L | D G L |

| 19 | Cimon | 510–450 | D G L P | Lucullus | 118–57/56 | (D) G L | D G L |

| 20 | Dion | 408–354 | (D) L | Brutus | 85–42 | (D) L P | D L |

| 21 | Agesilaus | c. 444 – c. 360 | (D) G L | Pompey | 106–48 | (D) G L | D G L |

| 22 | Alexander | 356–323 | (D) G L P | Julius Caesar (detailed article) | 100–44 | (D) G L P1 P2[1] | n/a |

| 23 | Demosthenes | 384–322 | D L | Cicero | 106–43 | (D) L | D L |

| 25[15] | Demetrius | d. 283 | (D) L | Mark Antony | 83–30 | (D) L P | D L |

- Notes

The two-volume edition of Dryden's translation contains the following biographies:

Volume 1. Theseus, Romulus, Lycurgus, Numa, Solon, Publicola, Themistocles, Camillus, Pericles, Fabius, Alcibiades, Coriolanus, Timoleon, Aemilius Paulus, Pelopidas, Marcellus, Aristides, Cato the Elder, Philopoemen, Flamininus, Pyrrhus, Marius, Lysander, Sulla, Cimon, Lucullus, Nicias, Crassus.

Volume 2. Sertorius, Eumenes, Agesilaus, Pompey, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Phocion, Cato the Younger, Agis, Cleomenes, Tiberius Gracchus and Gaius Gracchus, Demosthenes, Cicero, Demetrius, Mark Antony, Dion, Marcus Brutus, Aratus, Artaxerxes II, Galba, Otho.

- ^ The Perseus project also contains a biography of Caesar Augustus, in North's translation, but not from Plutarch's Parallel Lives: P

- ^ Though the majority of the Parallel Lives were written with the Greek hero (or heroes) placed in the first position followed by the Roman hero, there are three sets of Lives where this order is reversed: Aemilius Paulus/Timoleon, Coriolanus/Alcibiades and Sertorius/Eumenes.

- ^ At the time of composing this table there appears some confusion in the internal linking of the Perseus project webpages, responsible for this split in two references.

Reception

[edit]Plutarch's Parallel Lives has received widespread praise from notable figures throughout its centuries of popularity. The 1559 first French edition was hailed by French author and philosopher Montaigne, who commented "We dunces would have been lost if this book had not raised us out of the dirt". Beethoven, with the progression of his deafness, wrote in 1801, "I have often cursed my Creator and my existence. Plutarch has shown me the path of resignation. If it is at all possible, I will bid defiance to my fate, though I feel that as long as I live there will be moments when I shall be God's most unhappy creature ... Resignation, what a wretched resource! Yet it is all that is left to me." British General Gordon wrote "Certainly I would make Plutarch's Lives a handbook for our young officers. It is worth any number of 'Arts of War' or 'Minor Tactics'." Ralph Waldo Emerson called the Lives "a bible for heroes."[8]

The individual biographies have their own receptions in addition to responses to the work as a whole. The life of Antonius has been cited by multiple scholars as one of the masterpieces of the series.[16][17][18] Peter D'Epiro praised his depiction of Alcibiades as "a masterpiece of characterization."[19] Academic Philip A. Stadter singled out Plutarch's Pompey and Caesar as the greatest figures in the Roman biographies.[20] His biography of Caesar has been cited as proof that Plutarch is "loaded with perception".[21] Carl Rollyson's Essays in Biography states that "no biographer has surpassed him in summing up the essence of a life – perhaps because no modern biographer has believed so intensely as Plutarch did in 'the soul of men'."[21]

Within each translation and reiteration of Plutarch's Lives, translators and editors have manipulated his original work in order to put forward their own ideologies. George Wyndham's 1895 introduction to the Lives denounces how

Men cut down the genuine Lives to convenient lengths, for summaries and 'treasuries'...[they] epitomized Plutarch's matter and pointed his moral, grinding them to the dust of a classical dictionary and the ashes of a copybook headline.[6]

Here he is speaking of incomplete republications of Plutarch's original work, which had gained popularity but had been rehashed into brief, incomplete outlines that lacked Plutarch's original depth. Rebecca Nesvet argues that the 1683 translation of the text was constructed with the intention of incorporating a message of religious tolerance. Jacob Tonson, with assistance from John Dryden, republished Lives confirming Plutarch's paganism and demonstrating clearly that "adherence to a faith outside the one his readers were expected to follow should not disqualify a rational individual from political involvement in leadership". While the original text of Parallel Lives was produced to progress certain moral ideals, translators of the work have deviated from the original text to incorporate their own ethics.[22]

Plutarch's Parallel Lives has remained relevant centuries after being authored. His merging of biography and ethical commentary continues to be an invaluable reflection on human nature. Put quite plainly: "We find Plutarch surprisingly relevant today because nothing really has changed in human nature over the nineteen centuries since Plutarch wrote".[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ James Romm (ed.), Plutarch: Lives that Made Greek History, Hackett Publishing, 2012, p. vi.

- ^ a b c "Plutarch • Parallel Lives — Translator's Introduction". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2025-06-07.

- ^ Kimball, Roger. "Plutarch & the issue of character". The New Criterion Online. Archived from the original on 2006-11-16. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ McCutchen, Wilmot H. "Plutarch – His Life and Legacy". Archived from the original on 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- ^ Life of Alexander 1.2

- ^ a b Plutarch (1895). Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans. D. Nutt.

- ^ a b c McCutchen, Wilmot H. "Plutarch - His Life and Legacy". e-classics.com. Archived from the original on 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2025-06-10.

- ^ a b c McCutchen, Wilmot H. "Plutarch - His Life and Legacy". e-classics.com. Archived from the original on 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2025-06-10.

- ^ a b "Shakespeare's Plutarch, Vol. I (containing the main sources of Julius Caesar) | Online Library of Liberty". oll.libertyfund.org. Retrieved 2025-06-07.

- ^ Nesvet, Rebecca (2005-06-01). "Parallel Histories: Dryden's Plutarch and Religious Toleration". The Review of English Studies. 56 (225): 424–437. doi:10.1093/res/hgi059. ISSN 1471-6968.

- ^ Stadter, Philip A., ed. (2002-09-11). Plutarch and the Historical Tradition (0 ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203076637. ISBN 978-0-203-07663-7.

- ^ Chrysanthou, Chrysanthos S. (2018-02-19). Plutarch's >Parallel Lives< - Narrative Technique and Moral Judgement. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110574715. ISBN 978-3-11-057471-5.

- ^ Plutarch's Moralia, XV, edited and translated by F. H. Sandbach, Loeb Classical Library, 1987, pp. 3–11.

- ^ Kevin Herbert, "The Identity of Plutarch's Lost Scipio Archived 2019-07-13 at the Wayback Machine", in The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 78, No. 1 (1957), pp. 83–88. Plutarch only gives the name "Scipio". Herbert favours Scipio Aemilianus as the topic of the lost Life; he notes that Scipio Africanus was the subject of another (lost) biography by Plutarch.

- ^ Eran Almagor, "The Aratus and the Artaxerxes", in Mark Beck (editor), A Companion to Plutarch, pp. 278, 279. The n°24 in the Lamprias catalogue was a pair of biographies of Aratus and Artaxerxes, but they did not belong to the Parallel Lives.

- ^ Shakespeare's Principal Plays. Century Company. 1922.

- ^ Stadter, Philip A., ed. (2002). Plutarch and the Historical Tradition. Routledge. p. 159. ISBN 1-134-91319-2.

- ^ Plutarch (1906). Plutarch's Lives of Coriolanus, Caesar, Brutus, and Antonius: In North's Translation. Translated by North, Thomas. Clarendon Press.

- ^ D'Epiro, Peter (2010). The Book of Firsts: 150 World-Changing People and Events from Caesar Augustus to the Internet. Anchor Books. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-307-38843-8.

- ^ Brice, Lee L.; Slootjes, Daniëlle, eds. (2014). Aspects of Ancient Institutions and Geography: Studies in Honor of Richard J.A. Talbert. BRILL. p. 38. ISBN 978-9004283725.

- ^ a b Rollyson, Carl (2005). Essays in Biography. iUniverse. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-595-34181-8.

- ^ Nesvet, Rebecca (2005-06-01). "Parallel Histories: Dryden's Plutarch and Religious Toleration". The Review of English Studies. 56 (225): 424–437. doi:10.1093/res/hgi059. ISSN 1471-6968.

Further reading

[edit]- Schettino, Maria Teresa (2013). "The Use of Historical Sources". A Companion to Plutarch. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 417–436. doi:10.1002/9781118316450.ch28. ISBN 978-1-118-31645-0.

External links

[edit]Parallel Lives

View on GrokipediaBackground and Authorship

Plutarch's Life and Intellectual Context

Plutarch was born between 45 and 47 CE in Chaeronea, a small city in Boeotia, central Greece, to a family of modest wealth that valued education and philosophy.[1] His father, Ariston, provided early instruction in rhetoric and philosophy, fostering an environment steeped in Greek intellectual traditions despite the region's provincial status under Roman rule. Plutarch later pursued advanced studies in Athens under the Platonist philosopher Ammonius, where he engaged deeply with Platonic dialogues and ethical inquiry, laying the foundation for his lifelong commitment to moral philosophy.[1] Throughout his career, Plutarch combined scholarly pursuits with public service, traveling extensively to Alexandria and making multiple visits to Rome, where he lectured on philosophy and history to elite audiences, including figures like Quintilian and Pliny the Younger.[4] He held Roman citizenship, likely acquired through patronage, which facilitated his interactions with Roman administrators and intellectuals. In the mid-90s CE, Plutarch was appointed one of two lifelong priests at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi, a role he fulfilled for over fifteen years amid the sanctuary's declining oracle consultations, reflecting his dedication to preserving Greek religious and cultural heritage in a Roman-dominated world.[5] Intellectually, Plutarch aligned with Middle Platonism, emphasizing a literal interpretation of Plato's Timaeus and defending doctrines such as the soul's immortality and divine providence against skeptical critiques.[6] He synthesized Platonic metaphysics with ethical concerns drawn from Aristotle and the Stoics, prioritizing practical virtue over abstract speculation, as evident in his treatises on moral improvement through historical exemplars. This framework positioned him as a bridge between Hellenistic philosophy and Roman pragmatism, critiquing imperial excess while advocating harmonious Greco-Roman civic virtue.[1]Composition Timeline and Sources

Plutarch composed the Parallel Lives primarily during the reign of Emperor Trajan (98–117 CE), in the final two decades of his life, after the death of Domitian in 96 CE.[7] The work's dedication to his friend Quintus Sosius Senecio, a Roman consul in 99 CE and 107 CE, places its inception around the turn of the century, with individual biographies likely produced sequentially rather than as a unified collection from the outset.[8] Internal cross-references and allusions to contemporary events, such as Trajan's Dacian Wars, support a composition timeline extending into the 110s CE, though the full series was never formally arranged or published as a single volume during Plutarch's lifetime (c. 46–120 CE).[9] The relative chronology of the Lives relies on three main indicators: explicit references to other works within the biographies, allusions to Plutarch's evolving philosophical views, and historical details aligning with datable events.[10] Earlier pairs, such as those involving late Republican figures, may predate the imperial-era ones, but scholarly consensus holds that the majority postdate 96 CE, reflecting Plutarch's matured perspective as a priest at Delphi and public figure in Greece.[11] For sources, Plutarch drew extensively from earlier Greek historians like Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon for Greek subjects, often synthesizing their accounts with later compilations such as those of Diodorus Siculus.[12] Roman biographies relied on Hellenistic Greek treatments of Roman history, including Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Polybius, supplemented by oral traditions, inscriptions, and anecdotes gathered during Plutarch's multiple visits to Rome, where he interacted with Roman elites and accessed libraries.[12] He occasionally referenced Latin authors indirectly through Greek intermediaries or summaries, but prioritized verifiable reports over legendary material, as stated in prefaces like that to the Life of Alexander, where he critiques unreliable chroniclers and favors "ancient decrees" and eyewitness-derived memoirs. This method preserved fragments of lost works, enhancing the Lives' value despite Plutarch's selective emphasis on moral exemplars over exhaustive chronology.[12]Structure and Content

Pairing Mechanism and Surviving Works

Plutarch structured each entry in the Parallel Lives by pairing the biography of a notable Greek with that of a Roman figure whose career, virtues, or misfortunes showed meaningful parallels, often spanning similar domains such as statesmanship, military leadership, or lawgiving. This juxtaposition served to enable a concluding synkrisis, a formal comparison evaluating their moral qualities and life outcomes, though such epilogues are absent in some surviving instances.[11][13] Representative pairs encompass Theseus and Romulus as mythical founders of cities, Solon and Publicola as legislative reformers, Pericles and Fabius Maximus as strategic leaders during wartime crises, and Demetrius of Phalerum and Mark Antony as flamboyant rulers prone to excess.[2] From an original composition likely totaling around fifty biographies, forty-eight extant lives remain, forming twenty-three pairs alongside four unpaired singles: the Greek mercenary leader Aratus of Sicyon, the Persian king Artaxerxes II, and the short-reigning Roman emperors Galba and Otho (the latter constituting a Roman-only pairing without a Greek counterpart).[14][15] The Lamprias Catalogue, an ancient inventory of Plutarch's works attributed to his son, attests to broader plans but confirms losses, including the entire pair of the Theban general Epaminondas and Scipio Africanus.[14]Key Biographical Pairs and Themes Within Lives

![Plutarch's Parallel Lives manuscript][float-right] Plutarch paired biographies of illustrious Greeks and Romans whose lives shared parallels in achievements, moral dilemmas, or historical roles, enabling comparative analysis of character and conduct. Of the originally intended fifty biographies forming twenty-five pairs, twenty-three pairs survive intact, totaling forty-six lives, supplemented by four unpaired biographies: Aratus of Sicyon, Artaxerxes II of Persia, and the Roman emperors Galba and Otho.[2][16] Prominent pairs encompass foundational figures such as Theseus and Romulus, legendary founders who navigated civil strife and external threats to establish Athens and Rome, respectively, underscoring themes of heroic origins and civic institution-building.[16] Lawgivers Lycurgus and Numa Pompilius form another, contrasting Spartan austerity with Roman religious piety in shaping enduring polities.[16] Oratorical counterparts Demosthenes and Cicero highlight resistance to autocratic power through eloquence, with both facing exile and assassination for opposing Macedonian and Roman dictators.[2] Military exemplars include Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, whose relentless campaigns expanded empires but exposed vulnerabilities to overambition and betrayal, culminating in untimely deaths.[2] Similarly, Pericles and Fabius Maximus illustrate divergent approaches to leadership—bold democratic innovation versus cautious delay—amid existential wars against Persia and Hannibal.[2]| Greek Figure | Roman Figure | Key Parallels |

|---|---|---|

| Theseus | Romulus | Legendary city-founders, fratricide and unification |

| Lycurgus | Numa Pompilius | Legislative reformers, emphasis on discipline and religion |

| Demosthenes | Cicero | Rhetoricians combating tyranny |

| Alexander | Julius Caesar | Conquerors driven by glory, assassinated |

| Pericles | Fabius Maximus | Strategists in protracted conflicts |

.jpg/250px-Plutarch,_Parallel_Lives,_Oxford,_MS._Canonici_Greek_93_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Plutarch,_Parallel_Lives,_Oxford,_MS._Canonici_Greek_93_(cropped).jpg)