Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Phalanx

View on Wikipedia

The phalanx (pl.: phalanxes or phalanges)[1] was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar polearms tightly packed together. The term is used today to describe the use of this formation in ancient Greek warfare, but ancient Greek writers used it more broadly to describe any massed infantry formation regardless of its equipment.[2] In Greek texts, the phalanx may be deployed for battle, on the march, or even camped, thus describing the mass of infantry or cavalry that would deploy in line during battle. They marched forward as one entity.

The term itself, as used today, does not refer to a distinctive military unit or division (e.g., the Roman legion or the contemporary Western-type battalion), but to the type of formation of an army's troops. Therefore, this term does not indicate a standard combat strength or composition but includes the total number of infantry, which is deployed in a single formation known as a "phalanx".

Many spear-armed troops historically fought in what might be termed phalanx-like formations. This article focuses on the use of the military phalanx formation in Ancient Greece, the Hellenistic world, and other ancient states heavily influenced by Greek civilization.

History

[edit]The earliest known depiction of a phalanx-like formation occurs in the Sumerian Stele of the Vultures from the 25th century BC. Here the troops seem to have been equipped with spears, helmets, and large shields covering the whole body. Ancient Egyptian infantry were known to have employed similar formations. The first usage of the term phalanx comes from Homer's "φαλαγξ", used to describe hoplites fighting in an organized battle line. Homer used the term to differentiate the formation-based combat from the individual duels so often found in his poems.[3]

Historians have not arrived at a consensus about the relationship between the Greek formation and these predecessors of the hoplites. The principles of shield wall and spear hedge were almost universally known among the armies of major civilizations throughout history, and so the similarities may be related to convergent evolution instead of diffusion.

Traditionally, historians date the origin of the hoplite phalanx of ancient Greece to the 8th century BC in Sparta, but this is under revision. It is perhaps more likely that the formation was devised in the 7th century BC after the introduction of the aspis by the city of Argos, which would have made the formation possible. This is further evidenced by the Chigi vase, dated to 650 BC, identifying hoplites armed with aspis, spear, javelins, and other aspects of the panoply.[3]

Another possible theory as to the birth of Greek phalanx warfare stems from the idea that some of the basic aspects of the phalanx were present in earlier times yet were not fully developed due to the lack of appropriate technology. Two of the basic tactics seen in earlier warfare include the principle of cohesion and the use of large groups of soldiers. This would suggest that the Greek phalanx was rather the culmination and perfection of a slowly developed idea that originated many years earlier. As weaponry and armour advanced through the years in different city-states, the phalanx became complex and effective.[4]

Overview

[edit]

The hoplite phalanx of the Archaic and Classical periods in Greece c. 800–350 BC was the formation in which the hoplites would line up in ranks in close order. The hoplites would lock their shields together, and the first few ranks of soldiers would project their spears out over the first rank of shields. The phalanx therefore presented a shield wall and a mass of spear points to the enemy, making frontal assaults against it very difficult. It also allowed a higher proportion of the soldiers to be actively engaged in combat at a given time (rather than just those in the front rank).

Battles between two phalanxes usually took place in open, flat plains where it was easier to advance and stay in formation. Rough terrain or hilly regions would have made it difficult to maintain a steady line and would have defeated the purpose of a phalanx. As a result, battles between Greek city-states would not take place in just any location, nor would they be limited to sometimes obvious strategic points. Rather, many times, the two opposing sides would find the most suitable piece of land where the conflict could be settled. Typically, the battle ended with one of the two fighting forces fleeing to safety.[5]

The phalanx usually advanced at a walking pace, although it is possible that they picked up speed during the last several yards. One of the main reasons for this slow approach was to maintain formation. The formation would be rendered useless if the phalanx was lost as the unit approached the enemy and could even become detrimental to the advancing unit, resulting in a weaker formation that was easier for an enemy force to break through. If the hoplites of the phalanx were to pick up speed toward the latter part of the advance, it would have been for the purpose of gaining momentum against the enemy in the initial collision.[6] Herodotus said of the Greeks at the Battle of Marathon: "They were the first Greeks we know of to charge their enemy at a run." Many historians believe that this adaptation was precipitated by their desire to minimize their losses from Persian archery. According to some historians, the opposing sides could collide, possibly breaking many of the spears of the front row and maiming or killing the front part of the unit army due to the collision.

The spears of a phalanx had spiked butts (sauroter). In battle, the back ranks used the sauroter to finish fallen enemy soldiers.

Othismos or "pushing"

[edit]

The "physical pushing match" theory is one where the battle would rely on the valour of the men in the front line, whilst those in the rear maintained forward pressure on the front ranks with their shields, and the whole formation would consistently press forward trying to break the enemy formation. This is the most widely accepted interpretation of the ancient sources thus when two phalanx formations engaged, the struggle essentially became a pushing match. (The Ancient Greek word φάλαγξ – phalanx – could refer to a tree-trunk or log used as a roller, suggesting an image of physical effort.[7]) Historians such as Victor Davis Hanson point out that it is difficult to account for exceptionally deep phalanx formations unless they were necessary to facilitate the physical pushing depicted by this theory, as those behind the first two ranks could not take part in the actual spear thrusting.[8]

No Greek art ever depicts anything like a phalanx pushing match, so this hypothesis is a product of educated speculation rather than explicit testimony from contemporary sources and is far from being academically resolved. The Greek term for "push" was used in the same metaphorical manner as the English word is (for example it was also used to describe the process of rhetorical arguments) and so does not necessarily describe a literal physical push, although it is possible that it did.

For instance, if Othismos were to accurately describe a physical pushing match, it would be logical to state that the deeper phalanx would always win an engagement since the physical strength of individuals would not compensate for even one additional rank on the enemy side. However, there are numerous examples of shallow phalanxes holding off an opponent. For instance, at Delium in 424 BC, the Athenian left flank, a formation eight men deep, held off a formation of Thebans 25 deep without immediate collapse.[9] It is difficult with the physical pushing model to imagine eight men withstanding the pushing force of 25 opponents for a matter of seconds, let alone half the battle. The secret was the aspis, a convex shield that allowed a soldier to breathe while being crushed between men in front and back.

Such arguments have led to a wave of counter-criticism to physical shoving theorists. Adrian Goldsworthy, in his article "The Othismos, Myths and Heresies: The nature of Hoplite Battle", argues that the physical pushing match model does not fit with the average casualty figures of hoplite warfare nor the practical realities of moving large formations of men in battle.[10] This debate has yet to be resolved amongst scholars.

Practical difficulties with this theory also include the fact that, in a shoving match, an eight-foot spear is too long to fight effectively or even to parry attacks. Spears enable a formation of men to keep their enemies at a distance, parry attacks aimed at them and their comrades, and give the necessary reach to strike multiple men in the opposite formation. A pushing match would put enemies so close together that a quick stabbing with a knife would kill the front row almost instantly. The crush of men would also prevent the formation from withdrawing or retreating, which would result in much higher casualties than is recorded. The speed at which this would occur would also end the battle very quickly, instead of prolonging it for hours.

Shields

[edit]

Each individual hoplite carried his shield on his left arm, protecting not only himself but also the soldier to the left. This meant that the men at the extreme right of the phalanx were only half-protected. In battle, opposing phalanxes would try to exploit this weakness by attempting to overlap the enemy's right flank. It also meant that, in battle, a phalanx would tend to drift to the right (as hoplites sought to remain behind the shield of their neighbor). Some groups, such as the Spartans at Nemea, tried to use this phenomenon to their advantage. In this case, the phalanx would sacrifice its left side, which typically consisted of allied troops, in an effort to overtake the enemy from the flank. It is unlikely that this strategy worked very often, as it is not mentioned frequently in ancient Greek literature.[11]

There was a leader in each row of a phalanx, and a rear rank officer, the ouragos (meaning tail-leader), who kept order in the rear. The hoplites had to trust their neighbors to protect them and in turn be willing to protect their neighbors; a phalanx was thus only as strong as its weakest elements. The effectiveness of the phalanx therefore depended on how well the hoplites could maintain this formation in combat and how well they could stand their ground, especially when engaged against another phalanx. For this reason, the formation was deliberately organized to group friends and family close together, thus providing a psychological incentive to support one's fellows, and a disincentive, through shame, to panic or attempt to flee. The more disciplined and courageous the army, the more likely it was to win – often engagements between the various city-states of Greece would be resolved by one side fleeing before the battle. The Greek word dynamis (the "will to fight") expresses the drive that kept hoplites in formation.

Now of those, who dare, abiding one beside another, to advance to the close fray, and the foremost champions, fewer die, and they save the people in the rear; but in men that fear, all excellence is lost. No one could ever in words go through those several ills, which befall a man, if he has been actuated by cowardice. For 'tis grievous to wound in the rear the back of a flying man in hostile war. Shameful too is a corpse lying low in the dust, wounded behind in the back by the point of a spear.

Hoplite armament

[edit]Each hoplite provided his own equipment. The primary hoplite weapon was a spear around 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) in length called a dory. Although accounts of its length vary, it is usually now believed to have been seven to nine feet long (~2.1–2.7 m). It was held one-handed, with the other hand holding the hoplite's shield (aspis). The spearhead was usually a curved leaf shape, while the rear of the spear had a spike called a sauroter ('lizard-killer') which was used to stand the spear in the ground (hence the name). It was also used as a secondary weapon if the main shaft snapped or to kill enemies lying on the ground. This was a common problem, especially for soldiers who were involved in the initial clash with the enemy. Despite the snapping of the spear, hoplites could easily switch to the sauroter without great consequence.[13] The rear ranks used the secondary end to finish off fallen opponents as the phalanx advanced over them.

Throughout the hoplite era, the standard hoplite armour went through many cyclical changes.[14] An Archaic hoplite typically wore a bronze breastplate, a bronze helmet with cheekplates, as well as greaves and other armour. Later, in the classical period, the breastplate became less common, replaced instead with a corselet that some claim was made of linothorax (layers of linen glued together), or perhaps of leather, sometimes covered in whole or in part with overlapping metal scales.[15][16] Eventually, even greaves became less commonly used, although degrees of heavier armour remained, as attested by Xenophon as late as 401 BC.[17]

These changes reflected the balancing of mobility with protection, especially as cavalry became more prominent in the Peloponnesian War[18] and the need to combat light troops, which were increasingly used to negate the hoplite's role as the primary force in battle.[19] Yet bronze armour remained in some form until the end of the hoplite era. Some archaeologists have pointed out that bronze armour does not actually provide as much protection from direct blows as more extensive corselet padding, and have suggested its continued use was a matter of status for those who could afford it.[20] In the classical Greek dialect, there is no word for swordsmen; yet hoplites also carried either a short sword called the xiphos or a curved sword called the kopis, used as a secondary weapon if the dory was broken or lost. Samples of the xiphos recovered at excavation sites were typically around 60 cm (24 in) in length. These swords were double-edged (or single-edged in the case of the kopis) and could therefore be used as a cutting and thrusting weapon. These short swords were often used to stab or cut at the enemy's neck during close combat.[21]

Hoplites carried a circular shield called an aspis made from wood and covered in bronze, measuring roughly a metre (3.3 feet) in diameter. It spanned from chin to knee and was very heavy: 8–15 kg (18–33 lb). This medium-sized shield (fairly large for the period considering the average male height) was made possible partly by its dish-like shape, which allowed it to be supported with the rim on the shoulder. This was quite an important feature of the shield, especially for the hoplites who remained in the latter ranks. While these soldiers continued to help press forward, they did not have the added burden of holding up their shield. But the circular shield was not without its disadvantages. Despite its mobility, protective curve, and double straps the circular shape created gaps in the shield wall at both its top and bottom. (Top gaps were somewhat reduced by the one or two spears jutting out of the gap. In order to minimize the bottom gaps, thick leather curtains were used but only by an unknown percentage of the hoplites, possibly only in the first row since there were disadvantages as well: considerable weight on an already heavy shield and a certain additional cost.) These gaps left parts of the hoplite exposed to potentially lethal spear thrusts and were a persistent vulnerability for hoplites controlling the front lines.[22]

Phalangite armament

[edit]The phalanx of the Ancient Macedonian kingdom and the later Hellenistic successor states was a development of the hoplite phalanx. The "phalangites" were armed with a much longer spear, the sarissa, and less heavily armoured. The sarissa was the pike used by the ancient Macedonian army. Its actual length is unknown, but apparently it was twice as long as the dory. This makes it at least 14 feet (4.3 m), but 18 feet (5.5 m) appears more likely. (The cavalry xyston was 12.5 feet (3.8 m) by comparison.) The great length of the pike was balanced by a counterweight at the rear end, which also functioned as a butt-spike, allowing the sarissa to be planted into the ground. Because of its great length, weight and different balance, a sarissa was wielded two-handed. This meant that the aspis was no longer a practical defence. Instead, the phalangites strapped a smaller pelte shield (usually reserved for peltasts, light skirmishers) to their left forearm. Recent theories, including examination of ancient frescoes depicting full sets of weapons and armor, claim that the shields used were actually larger than the pelte but smaller than the aspis, hanging by leather strap(s) from the left shoulder or from both shoulders. The shield would retain handling straps in the inner curve, to be handled like a (smaller) aspis if the fight progressed to sword-wielding. Although in both shield size assumptions this reduced the shield wall, the extreme length of the spear kept the enemy at a greater distance, as the pikes of the first three to five ranks could all be brought to bear in front of the front row. This pike had to be held underhand, as the shield would have obscured the soldier's vision had it been held overhead. It would also be very hard to remove a sarissa from anything it stuck in (the earth, shields, and soldiers of the opposition) if it were thrust downwards, due to its length. The Macedonian phalanx was much less able to form a shield wall, but the lengthened spears would have compensated for this. Such a phalanx formation also reduced the likelihood that battles would degenerate into a pushing match.

Deployment and combat

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) |

A tetrarchia was a unit of four files (8-man columns in tight formation) and a tetrarchès or tetrarch was a commander of four files; a dilochia was a double file and a dilochitès was a double-file leader; a lochos was a single file and a lochagos was a file leader; a dimoiria was a half file and a dimoirites was a half-file leader. Another name for the half file was a hèmilochion with a hèmilochitès being a half-file leader.

Phalanx composition

[edit]The basic combat element of the Greek armies was either the stichos ("file", usually 8–16 men strong) or the enomotia ("sworn" and made up by 2–4 stichœ, totaling up to 32 men), both led by a dimœrites who was assisted by a decadarchos and two decasterœ (sing. decasteros). Four to a maximum of 32 enomotiæ (depending on the era in question or the city) formed a lochos led by a lochagos, who in this way was in command of initially a hundred hoplites to a maximum of around five hundred in the late Hellenistic armies. Here, the military manuals of Asclepiodotus and Aelian use the term lochos to denote a file in the phalanx. A taxis (mora for the Spartans) was the greatest standard hoplitic formation of five to fifteen hundred, led by a strategos (general). The entire army, a total of several taxeis or moræ was led by a generals' council. The commander-in-chief was usually called a polemarchos or a strategos autocrator.

Phalanx front and depth

[edit]Hoplite phalanxes usually deployed in ranks of eight men or more deep; the Macedonian phalanxes were usually 16 men deep, sometimes reported to have been arrayed 32 men deep. There are some notable extremes; at the battles of Leuctra and Mantinea, the Theban general Epaminondas arranged the left wing of the phalanx into a "hammerhead" of fifty ranks of elite hoplites deep (see below) and when depth was less important, phalanxes just four deep are recorded, as at the battle of Marathon.[23]

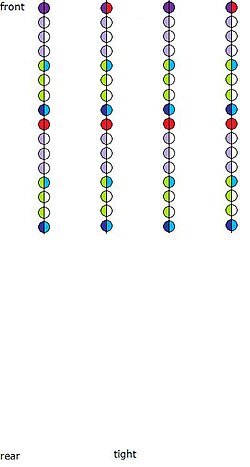

The phalanx depth could vary depending on the needs of the moment and plans of the general. While the phalanx was in march, an eis bathos formation (loose, meaning literally "in depth") was adopted in order to move more freely and maintain order. This was also the initial battle formation as, in addition, it permitted friendly units to pass through whether assaulting or retreating. In this status, the phalanx had twice the normal depth and each hoplite had to occupy about 1.8–2 metres (5 ft 11 in – 6 ft 7 in) in width. When enemy infantry was approaching, a rapid switch to the pycne (spelled also pucne) formation (dense or tight formation) was necessary. In that case, each man's space was halved and the formation depth returned to normal. An even denser formation, the synaspismos or sunaspismos (ultra-tight or locked shields formation), was used when the phalanx was expected to experience extra pressure, intense missile volleys or frontal cavalry charges. In synaspismos, the rank depth was half that of a normal phalanx and the width each man occupied was as small as 0.45 metres (1.5 ft).

Stages of combat

[edit]Several stages in hoplite combat can be defined:

Ephodos: The hoplites stop singing their pæanes (battle hymns) and move towards the enemy, gradually picking up pace and momentum. In the instants before impact, war cries (alalagmœ, sing. alalagmos) would be made. Notable war cries were the Athenian (eleleleleu! eleleleleu!) and the Macedonian (alalalalai! alalalalai!) alalagmœ.

Krousis: The opposing phalanxes meet each other almost simultaneously along their front.

Doratismos: Repeated, rapid spear thrusts in order to disrupt the enemy formation. The use of long spears would keep enemies apart as well as allow men in a row to assist their comrades next to them. The prodding could also open up a man to allow a comrade to spear him. Too hard prodding could get a spear stuck in a shield, which would necessitate someone in the back to lend his to the now-disarmed man.

Othismos: Literally "pushing" after most spears have been broken, the hoplites begin to push with their spears and spear shafts against their opponents' shields. This could be the longest phase.[citation needed]

Pararrhexis: Breaching the opposing phalanx, the enemy formation shatters and the battle ends. Cavalry would be used at this point to mop up the scattered enemy.[24]

Tactics

[edit]

Bottom: the diagonal phalanx utilised by the Thebans under Epaminondas. The strong left wing advanced while the weak right wing retreated or remained stationary.

The early history of the phalanx is largely one of combat between hoplite armies from competing Greek city-states. The usual result was rather identical, inflexible formations pushing against each other until one broke. The potential of the phalanx to achieve something more was demonstrated at Battle of Marathon (490 BC). Facing the much larger army of Darius I, the Athenians thinned out their phalanx and consequently lengthened their front, to avoid being outflanked. However, even a reduced-depth phalanx proved unstoppable to the lightly armed Persian infantry. After routing the Persian wings, the hoplites on the Athenian wings wheeled inwards, destroying the elite troop at the Persian centre, resulting in a crushing victory for Athens. Throughout the Greco-Persian Wars the hoplite phalanx was to prove superior to the Persian infantry (e.g., the battles of Thermopylae and Plataea).

Perhaps the most prominent example of the phalanx's evolution was the oblique order, made famous in the Battle of Leuctra. There, the Theban general Epaminondas thinned out the right flank and centre of his phalanx, and deepened his left flank to an unheard-of fifty men deep. In doing so, Epaminondas reversed the convention by which the right flank of the phalanx was strongest. This allowed the Thebans to assault in strength the elite Spartan troops on the right flank of the opposing phalanx. Meanwhile, the centre and right flank of the Theban line were echeloned back, from the opposing phalanx, keeping the weakened parts of the formation from being engaged. Once the Spartan right had been routed by the Theban left, the remainder of the Spartan line also broke. Thus, by localising the attacking power of the hoplites, Epaminondas was able to defeat an enemy previously thought invincible.

Philip II of Macedon spent several years in Thebes as a hostage, and paid attention to Epaminondas' innovations. On return to his homeland, he raised a revolutionary new infantry force, which was to change the face of the Greek world. Philip's phalangites were the first force of professional soldiers seen in Ancient Greece apart from Sparta. They were armed with longer spears (the sarissa) and were drilled more thoroughly in more evolved, complicated tactics and manoeuvres. More importantly, though, Philip's phalanx was part of a multi-faceted, combined force which included a variety of skirmishers and cavalry, most notably the famous Companion cavalry. The Macedonian phalanx now was used to pin the centre of the enemy line, while cavalry and more mobile infantry struck at the foe's flanks. Its supremacy over the more static armies fielded by the Greek city-states was shown at the Battle of Chaeronea, where Philip II's army crushed the allied Theban and Athenian phalanxes.

Weaknesses

[edit]The hoplite phalanx was weakest when facing an enemy fielding lighter and more flexible troops without its own such supporting troops. An example of this would be the Battle of Lechaeum, where an Athenian contingent led by Iphicrates routed an entire Spartan mora (a unit of 500–900 hoplites). The Athenian force had a considerable proportion of light missile troops armed with javelins and bows that wore down the Spartans with repeated attacks, causing disarray in the Spartan ranks and an eventual rout when they spotted Athenian heavy infantry reinforcements trying to flank them by boat.

The Macedonian phalanx had weaknesses similar to its hoplitic predecessor. Theoretically indestructible from the front, its flanks and rear were very vulnerable, and once engaged it may not easily disengage or redeploy to face a threat from those directions. Thus, a phalanx facing non-phalangite formations required some sort of protection on its flanks – lighter or at least more mobile infantry, cavalry, etc. This was shown at the Battle of Magnesia, where, once the Seleucid supporting cavalry elements were driven off, the phalanx was static and unable to go on the offensive against its Roman opponents (although they continued to resist stoutly and attempted a fighting withdrawal under a hail of Roman missiles, until the elephants posted on their flanks panicked and disrupted their formation).

The Macedonian phalanx could also lose its cohesion without proper coordination or while moving through broken terrain; doing so could create gaps between individual blocks/syntagmata, or could prevent a solid front within those sub-units as well, causing other sections of the line to bunch up.[25] In this event, as in the battles of Cynoscephalae and Pydna, the phalanx became vulnerable to attacks by more flexible units – such as Roman legionary centuries, which were able to avoid the sarissae and engage in hand-to-hand combat with the phalangites.

Another important area that must be considered concerns the psychological tendencies of the hoplites. Because the strength of a phalanx depended on the ability of the hoplites to maintain their frontline, it was crucial that a phalanx be able to quickly and efficiently replace fallen soldiers in the front ranks. If a phalanx failed to do this in a structured manner, the opposing phalanx would have an opportunity to breach the line which, many times, would lead to a quick defeat. This then implies that the hoplites ranks closer to the front must be mentally prepared to replace their fallen comrade and adapt to his new position without disrupting the structure of the frontline.[13]

Finally, most of the phalanx-centric armies tended to lack supporting echelons behind the main line of battle. This meant that breaking through the line of battle or compromising one of its flanks often ensured victory.

Classical decline and post-classical use

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2019) |

After reaching its zenith in the conquests of Alexander the Great, the phalanx began a slow decline, as Hellenistic successor states declined. The combined arms tactics used by Alexander and his father were gradually replaced by a return to the simpler frontal charge tactics of the hoplite phalanx. The expense of the supporting arms and cavalry, and the widespread use of mercenaries, caused the Diadochi to rely on phalanx vs. phalanx tactics during the Wars of the Diadochi.

The decline of the Diadochi and the phalanx was linked with the rise of Rome and the Roman legions from the 3rd century BC. The Battle of the Caudine Forks showed the clumsiness of the Roman phalanx against the Samnites. The Romans had originally employed the phalanx themselves[26] but gradually evolved more flexible tactics. The result was the three-line Roman legion of the middle period of the Roman Republic, the Manipular System. Romans used a phalanx for their third military line, the triarii. These were veteran reserve troops armed with the hastae or spear.[27] Rome conquered most of the Hellenistic successor states, along with the various Greek city-states and leagues. As these states ceased to exist, so did the armies which used the traditional phalanx. Subsequently, troops from these regions were equipped, trained and fought using the Roman model.

A phalanx formation called the phoulkon appeared in the late Roman army and Byzantine army. It had characteristics of the classical Greek and Hellenistic phalanxes, but was more flexible. It was used against cavalry more than infantry.

However, the phalanx did not totally disappear. In some battles between the Roman army and Hellenistic phalanxes, such as Pydna (168 BC), Cynoscephalae (197 BC) and Magnesia (190 BC), the phalanx performed well. It even drove back the Roman infantry. However, at Cynoscephalae and Magnesia, failure to defend the flanks of the phalanx led to defeat. At Pydna, the phalanx lost cohesion when pursuing retreating Roman soldiers. This allowed the Romans to penetrate the formation. Then, Roman close combat skills proved decisive. The historian Polybius details the effectiveness of the Roman legion against the phalanx. He deduces that the Romans refused to fight the phalanx where the phalanx was effective, Romans offered battle only when a legion could exploit the clumsiness and immobility of a phalanx.

Spear-armed troops continued to be important elements in many armies until reliable firearms became available. These did not necessarily fight as a phalanx. For example, compare the classical phalanx and late medieval pike formations.

Military historians[who?] have suggested that the Scots under William Wallace and Robert the Bruce consciously imitated the Hellenistic phalanx to produce the Scots' schiltron ("hedgehog"). However, long spears might have been used by Picts and others in Scotlands' Early Middle Ages. Prior to 1066, long spear tactics (also found in North Wales) might have been part of irregular warfare in Britain. The Scots used imported French pikes and dynamic tactics at the Battle of Flodden. However, Flodden found the Scots pitted against effective light artillery, while advancing over bad ground. The combination disorganised the Scottish phalanxes and permitted effective attacks by English longbowmen, and soldiers wielding shorter, handier polearms called bills. Some contemporary sources might say that the bills cut off the heads of Scottish pikes.

The pike was briefly reconsidered as a weapon by European armies in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It could protect riflemen, whose slower rate of fire made them vulnerable. A collapsible pike was invented but never issued. The Confederate Army considered these weapons for the American Civil War. Some were even manufactured but probably were never issued. Pikes were manufactured during World War II as "Croft's Pikes".

While obsolete in military practice, the phalanx remained in use as a metaphor of warriors moving forward as a single united block. This metaphor inspired several 20th-century political movements, notably the Spanish Falange and its ideology of Falangism.

See also

[edit]- Comparable formations

- Hoplite formation in art

- Pelopidas

- Point d'appui

- Roman infantry tactics

- Roman legion

- Sarissa

Notes

[edit]- ^ (Ancient Greek: φάλαγξ; plural φάλαγγες, phalanges)

- ^ For example, Arrian uses the term in his Array against the Alans when he refers to Roman legions.[citation needed]

- ^ a b Lendering, Jona (20 November 2008). "Phalanx and hoplites". Livius.org. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016.[better source needed]

- ^ Hanson (1991) pp. 66–67

- ^ Hanson (1991) pp. 88–89

- ^ Hanson (1991) pp. 90–91

- ^

Keegan, John (30 September 2011) [1993]. A History Of Warfare. Pimlico Military Classics (reprint ed.). London: Random House. p. 248. ISBN 9781446496510. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

phalanx - [...] (literally 'a roller') [...]

- ^ See Hanson,(1989) Ch. 15, for an introduction to the debate

- ^ Lazenby, (2004) p. 89

- ^ Goldsworthy (1997) pp. 1–26 in the academic journal War in History

- ^ Hanson (1991) pp. 91–92

- ^ Fragment #8D, lines 11–20: [...] οἳ μὲν γὰρ τολμῶσι παρ' ἀλλήλοισι μένοντες| ἔς τ' αὐτοσχεδίην καὶ προμάχους ἰέναι,| παυρότεροι θνῄσκουσι, σαοῦσι δὲ λαὸν ὀπίσσω·| τρεσσάντων δ' ἀνδρῶν πᾶσ' ἀπόλωλ' ἀρετή.| 15 οὐδεὶς ἄν ποτε ταῦτα λέγων ἀνύσειεν ἕκαστα,| ὅσσ', ἢν αἰσχρὰ μάθῃ, γίνεται ἀνδρὶ κακά·| ἀργαλέον γὰρ ὄπισθε μετάφρενόν ἐστι δαΐζειν| ἀνδρὸς φεύγοντος δηίῳ ἐν πολέμῳ·| αἰσχρὸς δ' ἐστὶ νέκυς κατακείμενος ἐν κονίῃσι| 20 νῶτον ὄπισθ' αἰχμῇ δουρὸς ἐληλάμενος.| [...] https://www.gottwein.de/Grie/lyr/lyr_tyrt_gr.php#Tyrt.8D

- ^ a b Hanson (1991)

- ^ See Wees (2004) pp. 156–178 for a discussion about archaeological evidence for hoplite armour and its eventual transformation

- ^ Snodgrass (1999)

- ^ Wees (2004) p. 165

- ^ Xenophon, (1986) p. 184

- ^ See Lazenby (2004) pp. 149–153, in relation to the deprivations of Cyracusian Cavalry and counter-methods

- ^ Xenophon (1986) pp. 157–161 "The Greeks Suffer From Slings and Arrows", and the methods improvised to solve this problem

- ^ Wees (2004) p. 189

- ^ Hanson (1991) p. 25

- ^ Hanson (1991) pp. 68–69

- ^ Phifer, Michiko (2012). A Handbook of Military Strategy and Tactics. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. p. 207. ISBN 978-9382573289. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ History of the Phalanx. ancientgreekbattles.net 3 September 2006

- ^ Goldsworthy, p. 102

- ^ Lendon, p. 182: The phalanx was known to the Romans in pre-Republic days, whose best fighting men were armed as hoplites.

- ^ Lendon, pp. 182–183

References

[edit]- Goldsworthy, A. (1997), "The Othismos, Myths and Heresies: The Nature of Hoplite Battle", War In History 4/1, pp. 1–26 doi:10.1177/096834459700400101.

- Hanson, Victor Davis (1989) The Western Way of War New York: Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 978-0-520-21911-3.

- Hanson, Victor Davis (1991) Hoplites: The Classical Greek Battle Experience ISBN 0-415-09816-5.

- Lazenby, J.F. (2004) The Peloponnesian War: a military study, Routledge ISBN 0-415-32615-X

- Lendon, J.E. (2005) Soldiers & Ghosts: A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11979-4. Book Review

- Wees, Hans van (2004), Greek warfare: Myths and Realities (Duckworth Press) ISBN 0-7156-2967-0.

- Xenophon (1986), Translated by George Cawkwell, The Persian Expedition (Penguin Classics)

- Snodgrass, A. (1999), Arms and Armour of the Ancient Greeks, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0801860733

Further reading

[edit]- Goldsworthy, Adrian: In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire (Orion, 2003) ISBN 0-7538-1789-6.

- Holland, T. Persian Fire, Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11717-1.

- Woodford, S.: An Introduction to Greek Art. Cornell University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-8014-9480-X.

External links

[edit]- Livius Archived 1 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine page on hoplite warfare.

- The Roman Maniple vs. The Macedonian Phalanx Archived 17 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Polybius, The Histories 18(28–32)

- The Apamea Phalangarius

- Images of the phalanx formation in ancient Greek warfare

Phalanx

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Core Concepts

Etymology and Terminology

The term phalanx derives from the Ancient Greek word φάλαγξ (phálanx), which originally denoted a finger bone, toe bone, or wooden log, evoking solidity and alignment.[5][6] This imagery extended metaphorically to describe a compact, rectangular battle formation of infantry standing shoulder to shoulder, resembling a rigid log or phalangeal row in its unyielding structure.[7][8] The word entered Latin as phalanx around the 1st century BCE, retaining its military connotation while also applying to anatomical bones, a usage persisting in modern English for both contexts.[5][6] In classical Greek military terminology, phalanx specifically referred to a dense tactical array of heavily armed foot soldiers, often hoplites, deployed in files (lochoi) and ranks for mutual protection via overlapping shields and projecting spears.[9] The formation emphasized collective cohesion over individual maneuver, with the term first appearing in literary sources like Homer's Iliad (circa 8th century BCE) in a looser sense of grouped warriors, evolving by the 4th century BCE in Xenophon's accounts to denote a standardized, unbroken infantry line.[6] Greek authors such as Thucydides and Xenophon used phalanx interchangeably for both the static battle order and the marching or encamped mass of troops, underscoring its versatility beyond combat.[9] Distinctions in terminology arose with regional and temporal variations: the Archaic and Classical hoplite phalanx (8th–4th centuries BCE) contrasted with the Hellenistic Macedonian phalanx, where soldiers were termed phalangites and the formation integrated longer pikes (sarissae) for deeper ranks, though ancient sources like Polybius applied phalanx broadly without rigid subtype nomenclature.[9] Modern historiography retains phalanx as the generic descriptor for these evolutions, avoiding anachronistic specificity unless contextualized by equipment or era, as the Greeks themselves prioritized functional description over formalized subclassification.[6]Fundamental Principles of Formation

The phalanx formation relied on close-order infantry alignment to create a unified front of overlapping shields and projecting spears, enabling collective defense and offense against enemy charges. Hoplites positioned themselves shoulder to shoulder, with each soldier's large, convex hoplon shield—approximately 90-100 cm in diameter and weighing 6-8 kg—covering the left side of his body while protecting the right side of the adjacent hoplite through overlap, forming an impenetrable shield wall approximately 1 meter high. [10] [11] This arrangement minimized individual exposure, as the shield's design and grip positioned it centrally on the left arm, ensuring the phalanx's left flank cohesion depended on disciplined alignment. [12] Typically structured in files of eight ranks deep and variable width based on available manpower—often hundreds wide—the formation distributed weight and force evenly across ranks, with front-line hoplites thrusting 2-3 meter dory spears overhand over the shield rim to target enemy faces and torsos, while rear ranks provided support via spear thrusts and forward pressure to maintain momentum. [13] [14] This depth allowed for sustained pushing (othismos), where the mass of bodies channeled force to disrupt opposing lines, though scholarly debate persists on whether combat emphasized shoving en masse or individual spear work amid gradual attrition. [10] Uniform equipment and training ensured interchangeability, with the phalanx advancing as a rigid block on level terrain to preserve alignment, as deviations could expose flanks to cavalry or skirmishers. [15] In principle, the phalanx's effectiveness stemmed from its geometric simplicity and reliance on collective discipline over individual prowess, transforming disparate citizen-soldiers into a cohesive instrument of shock combat that prioritized depth for stability and width for envelopment potential. [16] Later Macedonian variants extended these principles with deeper formations—up to 16 ranks—and longer sarissae (4-6 meters) held underarm to create multiple spear layers, amplifying reach and deterrence while retaining the core shield-lock and file structure. [17] Empirical evidence from battles like Marathon (490 BCE), where a phalanx depth of eight ranks held against Persian numbers, underscores how these principles enabled smaller Greek forces to repel larger, looser arrays through superior cohesion. [18]Historical Origins and Evolution

Emergence in Archaic Greece

The phalanx formation emerged in Archaic Greece amid the transition from the Greek Dark Ages to the early polis era, approximately between 750 and 650 BC, driven by demographic recovery, agricultural intensification, and interstate rivalries over arable land. Following a period of decentralized raiding and loose warrior bands depicted in Homeric epics, Greek communities increasingly resorted to pitched battles to resolve territorial disputes, favoring massed infantry over individual heroics. This shift coincided with the widespread adoption of bronze-working techniques and trade networks that made heavy armor accessible to a broader class of free male farmers, transforming warfare into a collective endeavor reliant on disciplined close-order fighting.[19][20] Archaeological evidence underscores this evolution, with the earliest hoplite panoply components—such as bronze Corinthian-style helmets, greaves, and large round aspis shields (approximately 90-100 cm in diameter)—appearing in graves and sanctuaries from the late 8th century BC onward, particularly in regions like Argos and Sparta. These artifacts indicate a move toward equipment optimized for thrusting in formation rather than throwing or dueling, as the aspis's size necessitated side-by-side alignment to cover unprotected flanks and enable shield overlap. By the mid-7th century BC, vase paintings from Attica and Corinth depict armed warriors in linear arrays, suggesting tactical experimentation with depth and cohesion, though formations likely remained fluid compared to later Classical rigidity.[20][21] Literary sources provide the clearest contemporary glimpses, with Spartan poet Tyrtaeus (active c. 650 BC) exhorting hoplites to "stand fast beside" comrades, thrusting spears forward while locking shields, and emphasizing mutual support over personal glory—phrases implying an embryonic phalanx push (othismos) against enemy lines. This contrasts with the Iliad's (composed c. 750-700 BC) portrayal of spaced-out combatants, indicating a tactical refinement in the 7th century BC, possibly pioneered in Sparta during conflicts like the Second Messenian War (c. 685-668 BC). Scholarly consensus holds that the phalanx crystallized as a response to the causal imperatives of heavy armament and battlefield geometry, where unshielded sides invited rout, though debates persist: traditional views posit a revolutionary "hoplite reform" around 700 BC tying military change to political equality, while revisionists argue for gradual adaptation without abrupt overhaul, citing inconsistent early evidence for uniform depth or ritualized combat.[22][19][23]Classical Hoplite Phalanx

The classical hoplite phalanx emerged as the dominant infantry formation in Greek city-states during the 5th and early 4th centuries BCE, comprising heavily armed citizen-soldiers who fought in close-order ranks to maximize collective pushing power and shield coverage. Hoplites, named for the hoplon—a large, round bronze-faced shield approximately 90 cm in diameter and weighing 7-10 kg—equipped themselves with bronze armor including a muscle cuirass (15-20 kg), greaves, and Corinthian helmet, alongside a 2-3 m thrusting spear (dory) and short sword (xiphos). This panoply, totaling 25-30 kg, enabled sustained close combat but demanded rigorous physical conditioning and formation discipline.[20][12] Formations typically featured 8-16 ranks deep, with each hoplite allotted 75-90 cm of frontage to allow shield overlap (aspis en tais aspisi) and uniform spear projection over the right shoulder of the man ahead. The structure prioritized depth for othismos—the shield-push phase where rear ranks propelled front-line fighters forward, aiming to compress and demoralize opponents through superior mass rather than maneuver. Deployment occurred on level terrain to preserve cohesion, with files (lochoi) of kin or locals fostering mutual reliance, as individual flight exposed unshielded right sides to enemy thrusts.[12][24] Tactics emphasized a steady advance in cadence to the paean hymn, accelerating into a final rush before halting for the spear exchange, followed by grinding attrition until one side yielded. Effectiveness hinged on morale and alignment; disruptions from uneven ground or archery, as at the Battle of Delium (424 BCE) where Boeotians exploited Athenian wavering per Thucydides' account, could cascade into tarache (panic rout). Yet the phalanx proved decisive in Persian Wars clashes like Plataea (479 BCE), where 10,000+ hoplites repelled vastly larger forces through disciplined frontal pressure.[25][3] Innovations tested limits, notably at Mantinea (418 BCE), where Spartans maintained 12-deep ranks against Athenian 8-deep lines, leveraging experience for victory via prolonged othismos. By Leuctra (371 BCE), Theban commander Epaminondas deepened his left wing to 50 ranks—contrasting standard shallowness—concentrating 6,000+ men to shatter elite Spartan hippeis through overwhelming local superiority, exposing phalanx rigidity to asymmetric depth tactics while affirming its core reliance on unbroken cohesion for breakthroughs.[26][23] This formation's empirical success derived from biomechanical efficiency: locked shields distributed force, while overarm spears pierced gaps efficiently at 2-3 m range, outperforming looser barbarian arrays in head-on engagements but faltering against envelopment without supporting peltasts or cavalry, as Spartan hegemony waned post-Leuctra amid such vulnerabilities.[24][27]Macedonian and Hellenistic Transformations

Philip II of Macedon (r. 359–336 BC) initiated the transformation of the traditional hoplite phalanx into the Macedonian variant through military reforms that emphasized professionalism and technological innovation. He introduced the sarissa, a pike roughly 4 to 6 meters long, doubling the reach of the standard Greek dory spear of about 2 to 3 meters, which allowed multiple ranks of pikemen to engage simultaneously with up to five spear points protruding from the formation's front.[28][29] This shift necessitated lighter armor, including smaller round shields (peltae) instead of large hoplon shields, and the abandonment of greaves to improve mobility under the weapon's weight, enabling Macedonian infantrymen—often drawn from peasant levies—to form deeper arrays of 16 to 32 ranks compared to the typical 8 to 12 of hoplite phalanxes.[30][31] These changes created a more rigid, forward-thrusting infantry force optimized for shock against less cohesive opponents, as demonstrated at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, where the Macedonian phalanx held the center while Companion cavalry flanked the Greek allies.[32] Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 BC) refined this system by integrating the phalanx as the "anvil" to pin enemy centers, coordinating it with elite heavy cavalry charges on the flanks in the "hammer and anvil" tactic, which proved decisive in battles like Issus (333 BC) and Gaugamela (331 BC) against Persian forces.[33][34] The phalangites, supported by hypaspists (shield-bearers) for flexibility and lighter troops for screening, maintained cohesion over extended campaigns, leveraging the sarissa's reach to outrange foes while cavalry exploited breakthroughs.[35] In the Hellenistic era following Alexander's death in 323 BC, his successors (Diadochi) perpetuated the Macedonian phalanx as the core of armies in kingdoms like the Seleucid and Ptolemaic realms, but with adaptations reflecting larger scales and diverse terrains. Phalanxes grew to depths of up to 32 ranks and widths accommodating thousands, incorporating regional recruits and mercenaries, though often at the expense of the integrated mobility seen under Philip and Alexander, as cavalry roles diminished relative to the infantry's mass.[36] Innovations included pairing phalangites with war elephants for shock support, as in Seleucid forces, yet the formation's emphasis on depth and pike length persisted, prioritizing frontal dominance over the hoplite phalanx's individual prowess.[37] This evolution marked a shift toward a more specialized, combined-arms doctrine, though vulnerabilities in maneuverability emerged against adaptable foes like Roman legions in later conflicts.[38]Equipment and Armament

Hoplite Panoply and Shields

The hoplite panoply represented the comprehensive defensive armament of the Greek citizen-soldier, emphasizing protection for close-order infantry combat within the phalanx. Core components included a bronze Corinthian helmet enclosing the head and neck, a cuirass such as the bell-shaped or muscle cuirass forged from hammered bronze sheets to safeguard the torso, and greaves of molded bronze fitting the shins. These elements, supplemented by a short sword (xiphos) and primary spear (dory), formed a load estimated at 20 to 30 kilograms, restricting mobility but enabling sustained shield wall integrity. Archaeological evidence from sanctuaries like Olympia reveals dedications of such gear dating to the 7th century BCE, indicating widespread adoption among propertied classes capable of affording bronze craftsmanship.[39][20][40] Central to the panoply was the aspis shield, a large convex disk essential for both individual defense and collective formation cohesion. Measuring approximately 90 to 100 centimeters in diameter and weighing 6 to 8 kilograms, the aspis consisted of a wooden core—often laminated poplar or willow—clad in leather or rawhide, with a bronze rim for reinforcement and sometimes a facing or central boss (omphalos) for added durability. Its unique gripping system featured a central porpax armband securing the left forearm and an antilabe handgrip at the inner rim, positioning the shield to cover from chin to knee while allowing spear thrust over the top. This design, evidenced in vase paintings and rare surviving fragments, permitted interlocking edges (synaspismos) to create an impermeable barrier against enemy probes.[41][19] Variations in panoply existed across city-states and periods, with Spartan hoplites favoring fuller bronze ensembles for elite cohesion, while poorer fighters might substitute linen corslets (linothorax) or forgo greaves to reduce cost and weight. The shield's prominence derived from its nomenclature—hoplon meaning "tool" or "implement," from which "hoplite" stems—underscoring its role as the phalanx's foundational element. Historical accounts and reconstructive analyses confirm that the aspis's heft demanded physical conditioning, contributing to the hoplite's status as a middling landowner rather than universal conscript.[42][20]Phalangite Weapons and Sarissa

Phalangites, the infantry of the Macedonian phalanx, relied primarily on the sarissa, a long pike introduced by Philip II of Macedon in the mid-4th century BC to extend reach against hoplite formations.[43] The sarissa measured approximately 4 to 6 meters in length, constructed from wood such as cornel or ash, with a bronze spearhead at one end and a smaller iron butt-spike for planting in the ground or as a secondary striking point.[29] This length allowed the front five or six ranks to present a dense wall of points, overwhelming shorter spears in direct clashes, as evidenced by Macedonian successes at battles like Chaeronea in 338 BC.[44] Ancient accounts, including those from Polybius, describe variations in length over time, with earlier Macedonian sarissae likely shorter than later Hellenistic versions, reflecting adaptations for tactical advantages.[45] Wielded two-handed and angled upward in formation, the sarissa demanded disciplined coordination, rendering individual maneuvers impractical and emphasizing collective thrusting over personal combat.[43] To compensate for the two-handed grip, phalangites carried a smaller shield, the pelte, typically 60-70 cm in diameter, made of wicker or wood covered in hide, slung from the neck or shoulder rather than held actively.[46] This lighter pelte provided minimal protection compared to the hoplite's aspis, prioritizing mobility and sarissa handling over heavy shielding.[29] Secondary armament included a short sword, such as the xiphos with its straight, leaf-shaped blade for thrusting or the curved kopis for slashing, used primarily if the phalanx broke or in close-quarters pursuit.[46] Phalangites often forwent the traditional dory spear, as the sarissa fulfilled the primary offensive role, though elite units like the hypaspists might retain shorter spears for versatility.[44] Armor was comparatively light, featuring a pilos helmet, linothorax cuirass of layered linen, and occasionally greaves, enabling endurance during prolonged marches and maneuvers essential to Philip's and Alexander's campaigns.[43] This equipment suite shifted the phalanx from the armored, shield-dominant hoplite model to a pike-focused system, optimizing for depth and projection of force.[45]Comparative Armament Variations

The armament of the classical Greek hoplite phalanx centered on the dory spear, typically 1.8 to 2.7 meters in length and weighing 1 to 2 kilograms, designed for one-handed thrusting or overarm stabbing in dense melee. This was complemented by the aspis shield, a convex bronze-faced wooden disc approximately 90 centimeters in diameter and 7 to 8 kilograms in weight, which interlocked with adjacent shields to form a protective barrier while allowing the spear's use over or beside it. Secondary armament included the xiphos sword, about 60 centimeters long, for close-quarters cutting after spear breakage. Body protection comprised a bronze muscle cuirass (5 to 10 kilograms), greaves, and a full-faced Corinthian helmet, totaling an estimated 20 to 30 kilograms for the full panoply, prioritizing durability in sustained hand-to-hand combat.[47][48] In the Macedonian phalanx under Philip II and Alexander III, the sarissa pike—4 to 6 meters long and up to 5 kilograms, wielded two-handed—replaced the dory, creating overlapping points from multiple ranks for superior reach in frontal assaults, though its length reduced individual maneuverability and required rearward bracing. The pelte shield, smaller at 60 to 75 centimeters and 2 to 4 kilograms, was often slung from the neck or shoulder to free both hands, offering minimal lower-body coverage compared to the aspis. Armor shifted to lighter linothorax (layered linen, 3 to 5 kilograms) or scale/mail variants, with helmets like the Phrygian style but typically omitting greaves; this reduced encumbrance for pike handling and marching but increased vulnerability to leg wounds. The kopis sword served as backup, though pike doctrine minimized its deployment.[49][50] These differences stemmed from tactical evolutions: hoplite gear supported versatile, citizen-soldier engagements on varied terrain, where shield walls and personal armor countered pushes and breaks, as seen in battles like Marathon (490 BCE). Macedonian variations optimized massed pike thrusts for breaking looser foes like Persians at Gaugamela (331 BCE), trading armor mass for depth and projection, yet exposing flanks to mobile threats, a limitation evident against Roman legions at Cynoscephalae (197 BCE). Empirical outcomes indicate the sarissa's reach advantage in ideal conditions outweighed hoplite balance only when combined with cavalry and terrain control, per analyses of Polybius's accounts.[51]| Armament Component | Hoplite Specification | Phalangite Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Weapon | Dory spear, 1.8–2.7 m, one-handed | Sarissa pike, 4–6 m, two-handed |

| Shield | Aspis, ~90 cm diameter, 7–8 kg | Pelte, 60–75 cm, 2–4 kg |

| Body Armor Weight | Bronze panoply, 20–30 kg total | Linothorax/scale, 10–15 kg total |

Formation, Deployment, and Tactics

Compositional Structure and Depth

The hoplite phalanx of classical Greece was typically organized into files (stichoi) of eight men deep, with the front rank holding spears overhand and rear ranks providing support through pressure and replacement of fallen comrades.[25] This depth allowed for a balance between forward thrusting power and rearward cohesion, as deeper formations risked disorder while shallower ones lacked momentum in the othismos (shoving) phase.[52] Units were subdivided into smaller tactical elements, such as the Spartan enōmotia (approximately 32 men in four files of eight), which formed the basic building block scalable to larger lochoi (companies) of 100-200 men, enabling city-state armies to assemble phalanxes hundreds wide depending on manpower.[25] Variations in depth occurred for tactical emphasis; for instance, the Thebans under Epaminondas at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE deployed their left wing in 50 ranks deep to achieve local superiority and break the Spartan line through concentrated pressure.[25] Athenian and other city-state phalanxes often maintained eight ranks as standard, with files aligned by tribal or district groupings to foster unit cohesion among citizen-militia.[52] Depth was not rigidly fixed, adapting to terrain or numbers, but exceeding 12 ranks generally compromised maneuverability without proportional gains in combat effectiveness.[52] In the Macedonian adaptation under Philip II and Alexander III, the phalanx evolved into a denser, deeper formation of 16 ranks, organized into syntagmata of 256 pezhetairoi (foot companions) arranged in 16 files by 16 ranks, with files led by dekarchs (file-leaders).[53] This structure, using the sarissa pike, projected multiple spear points forward while rear ranks angled weapons for layered defense, enhancing penetration against looser foes but requiring flat terrain for alignment.[54] Hellenistic successors maintained this 16-deep standard, sometimes extending to 32 ranks for emphasis, though evidence suggests minimal combat advantage beyond 16 due to diminished rear influence on the front line.[54] The compositional shift prioritized professional drill over militia flexibility, with larger taxis (battalions) of multiple syntagmata allowing scalable depths for combined arms integration.[53]Stages of Engagement

The engagement of the classical hoplite phalanx unfolded in sequential phases, emphasizing disciplined advance and close-quarters intensity to exploit collective force over individual prowess. The initial ephodos (advance) saw hoplites cease their paeans—ritual battle hymns—and proceed from a measured march to a trot or run in the final moments, covering distances of 100-200 meters to contact while preserving alignment and shield interlock to minimize disruption.[52] This momentum aimed to psychologically unsettle foes and enable a cohesive impact, with deeper phalanxes (typically 8-16 ranks) better sustaining speed due to rearward pressure.[52] Upon collision, the krousis (striking) phase dominated, wherein front-rank promachoi thrust eight-foot doru spears primarily overhand over adjacent shields to target exposed faces, necks, or underarms, while underhand stabs probed lower vulnerabilities.[52] Rear ranks contributed by shoving forward via spear-butts or shields, amplifying pressure without direct weapon use, as evidenced in Thucydides' accounts of battles like Mantinea (418 BC), where sustained stabbing depleted enemy fronts before broader collapse.[52] Combat here prioritized stabbing over slashing, with the convex aspis shield (circa 90 cm diameter, 7-10 kg) deflecting blows and enabling overlapped protection (synaspismos).[52] Spear breakage after 5-10 minutes often transitioned to othismos (pushing), a massed shield-to-shield exertion where the phalanx's depth translated into overwhelming forward force, akin to a human battering ram, to buckle enemy cohesion and induce panic.[52] Xenophon's Hellenica describes this at Coronea (394 BC), where Theban pressure shattered Spartan lines through cumulative shoving, leading to rout (trope).[52] While traditionally viewed as literal, some analyses, informed by skeletal trauma from sites like Visviki (Argos, 7th-5th centuries BC) showing groin and thigh wounds, suggest othismos encompassed prolonged melee with secondary weapons (xiphos shortswords) rather than exclusive scrum, highlighting debate over ritualized duels versus attrition warfare.[55] Breakthrough triggered diōxis (pursuit), with victors discarding heavy gear to chase fleeing hoplites, inflicting heavy casualties as per Herodotus' Thermopylae aftermath (480 BC), where pursuit amplified kills beyond the clash.[52] In Macedonian variants, engagement shifted to standoff pike presentation, with 16-32 rank pezetairoi advancing at 100 meters to level 4-6 meter sarissai, impaling assailants at distance without hoplite-style intimacy, as at Gaugamela (331 BC) where Persian charges faltered against the bristle.[56] This evolution prioritized reach over push, rendering classical stages obsolete by Hellenistic eras.[56]Maneuverability and Strategic Applications

The hoplite phalanx possessed inherently limited maneuverability, stemming from its dense packing of heavily armored infantry in files typically eight ranks deep, with soldiers maintaining close spacing to overlap shields and present a continuous spear front. This configuration, while optimizing frontal pushing power, impeded rapid turns, oblique advances, or wheeling motions, as any disruption in alignment risked exposing vulnerabilities to enemy exploitation. Empirical reconstructions demonstrate that minimal spacing—approximately one meter per man—constrained footwork, allowing only basic evolutions like the countermarch under ideal conditions on flat terrain, but faltering amid rough ground or prolonged combat due to fatigue from 60-pound loads.[57][58][52] Strategically, the formation was deployed for decisive frontal engagements in open fields, leveraging collective momentum to break enemy centers rather than pursuing skirmishes or sieges, as Greek city-states prioritized short, high-stakes battles to minimize manpower losses among citizen-soldiers. In constricted theaters like narrow plains or passes, it amplified defensive efficacy by negating flanking opportunities, exemplified in the Spartan stand at Thermopylae in 480 BCE, where terrain channeled Persian assaults into a grinding attrition the phalanx could sustain through disciplined cohesion. Offensively, it enabled ritualized "pushing matches" where rear ranks propelled forwards, shattering less resolute foes, though success hinged on moral superiority and avoiding encirclement.[25][59][60] The Macedonian phalanx, transformed by Philip II around 359–336 BCE with 5–6 meter sarissas, exacerbated maneuverability constraints through extended pike lengths that demanded two-handed grips, deeper formations (up to 16 ranks), and glacial advances limited to straight-line charges, rendering lateral shifts or retreats precarious without support. Light rear armor further amplified flank fragility during any disorder, as soldiers struggled to redress pikes under pressure.[61] In Hellenistic applications, it served as a tactical anchor in combined-arms doctrines, immobilizing foes centrally to facilitate cavalry or hypaspist envelopments—the "hammer and anvil"—as Alexander demonstrated at Gaugamela in 331 BCE, where the phalanx's rigidity pinned Darius III's center, allowing decisive wing maneuvers despite the formation's immobility. This integration mitigated inherent inflexibility, enabling conquest across varied theaters, though overreliance on perfect terrain and coordination exposed it to Roman manipular adaptability in later clashes like Cynoscephalae in 197 BCE.[32][62][63]Strengths and Empirical Effectiveness

Disciplined Cohesion Advantages

The phalanx's disciplined cohesion provided a decisive physical advantage by enabling overlapping shields and spear points to form a continuous barrier that distributed combat pressure across the entire formation rather than individual soldiers. This interlocking structure, maintained through rigorous training and synchronized movement, minimized vulnerabilities to penetration from enemy thrusts or missiles, as each hoplite protected the right side of his neighbor while relying on the left-side protection in turn.[64][10] Discipline ensured the formation's integrity during the advance and othismos (massed shove), allowing hoplites to exert collective force equivalent to several times that of isolated warriors, overwhelming less cohesive opponents through sustained pushing and stabbing without breaking ranks. Historical analyses emphasize that this unity transformed the phalanx into a single, maneuverable entity capable of absorbing shocks that would rout looser infantry lines, as gaps from indiscipline invited exploitation and collapse.[25][15] Psychologically, the tight cohesion fostered mutual dependence and accountability, reducing panic and desertion by making individual flight tantamount to betraying comrades, thereby enhancing morale and resilience under pressure. This social reinforcement, rooted in polis values of collective honor, intimidated adversaries with the spectacle of an unyielding wall, often prompting enemy disorder before direct clash.[10][65] In comparative terms, the phalanx's cohesion outperformed contemporaneous levies or tribal warriors, whose fragmented tactics yielded to the Greek formation's ability to maintain depth and alignment on favorable terrain, amplifying effective manpower density. Scholarly examinations note that such discipline not only prolonged engagement endurance but also enabled tactical flexibility, like wheeling or echelon shifts, when executed flawlessly by veteran units.[2][65]Evidence from Key Battles

The Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE provides early evidence of the hoplite phalanx's effectiveness against numerically superior foes, as approximately 10,000 Athenian and Plataean hoplites advanced in close formation to defeat a Persian expeditionary force of 20,000 to 25,000 infantry and cavalry, inflicting heavy casualties while suffering minimal losses of around 192 dead compared to 6,400 Persian fatalities. [59] The phalanx's interlocking shields and spear thrusts enabled a rapid charge that disrupted Persian light infantry and archers, whose lighter armament and looser order proved inadequate for sustained frontal pressure against the cohesive Greek ranks. [66] At Plataea in 479 BCE, a Greek allied phalanx of roughly 40,000 hoplites, including Spartans, Athenians, and Corinthians, repelled a Persian army exceeding 100,000 under Mardonius, with the Greek formation's depth and discipline allowing it to withstand missile attacks and counter with a shield-wall push that shattered the enemy center, leading to Persian rout and Mardonius's death. [59] This victory underscored the phalanx's resilience in prolonged engagements, where mutual support among hoplites prevented individual routs and amplified collective thrusting power over dispersed opponents. The Battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE demonstrated tactical innovations enhancing phalanx efficacy, as Theban general Epaminondas deployed a 50-rank-deep left-wing phalanx of elite troops, including the Sacred Band, against the Spartan right, overwhelming their traditional 12-rank formation through superior mass and momentum in an oblique assault that collapsed Spartan command and killed over 1,000 of 10,000 Spartiates engaged. [67] [68] The deeper formation's concentrated pressure exploited Spartan rigidity, evidencing how phalanx cohesion could negate elite opponents when depth amplified othismos—the shield shove and spear thrust—causing breaks in enemy lines without extensive flanking. Macedonian phalanx adaptations further validated the formation's potential when integrated with combined arms, as at Chaeronea in 338 BCE, Philip II's sarissa-armed phalangites of 16 ranks held and advanced against a Greek hoplite alliance, pinning the center while cavalry under Alexander exploited gaps, resulting in over 1,000 Greek dead including Theban commanders and securing Macedonian hegemony. [59] Similarly, at Gaugamela in 331 BCE, Alexander's phalanx of up to 16,000 men maintained formation integrity against Darius III's vast host, absorbing scythed chariot charges and infantry assaults to create openings for Companion cavalry breakthroughs, contributing to the Persian collapse despite facing odds of over 5:1. [68] These engagements highlight the phalanx's empirical strength in frontal holding actions, where extended reach and density deterred penetration, though success hinged on avoiding isolation from supporting elements.Causal Factors in Victories

The hoplite phalanx's successes in pitched battles against Persian forces derived from its heavy armament and disciplined formation, which neutralized enemy missile advantages and enabled decisive melee dominance. At Marathon on September 12, 490 BC, roughly 10,000 Greek hoplites charged approximately 20,000–25,000 Persians at double-quick pace, closing to 200 meters in eight seconds to disrupt archery and exploit the phalanx's bronze panoply against lighter wicker shields and bows, resulting in 6,400 Persian dead versus 192 Greeks.[69][70] Topographical constraints, including marshy flanks that limited Persian cavalry, further amplified the phalanx's forward momentum and cohesion, preventing envelopment. Discipline among citizen-soldiers, motivated by communal defense rather than pay, sustained the interlocking shield wall under pressure, allowing thrusting spears to outrange and impale foes disorganized by the sudden assault. Victor Davis Hanson emphasizes that this "Western way" prioritized brief, high-intensity infantry clashes where equipment superiority—greaves, cuirasses, and 8-foot doru spears—overcame numerical disadvantages against less resolute levies.[72] Empirical outcomes, such as Plataea in 479 BC where 40,000 Greeks routed 120,000 Persians with minimal losses, underscore how phalanx depth (typically 8–12 ranks) generated cumulative shoving force to shatter enemy centers once engaged.[19] The Macedonian phalanx elevated these factors through professional training, longer sarissae (4–7 meters), and integrated arms, yielding hegemony over Greek rivals. At Chaeronea on August 2, 338 BC, Philip II's 30,000-man army, with its 16-rank deep pike phalanx, pinned the Athenian-Theban alliance of 35,000 while Alexander's cavalry (1,800 strong) outflanked the left, killing 1,000 Athenians including commanders and capturing 2,000 for 1,000 Macedonian losses.[73][74] The sarissa's reach created an impenetrable bristle that repelled hoplite charges, while drilled maneuvers maintained alignment on uneven terrain, contrasting with the Greeks' part-time militias. Earlier, at Leuctra in July 371 BC, Theban depth (50 ranks on the left) concentrated 6,000 against 10,000 Spartans, collapsing their elite wing in a 3:1 loss ratio through oblique pressure that exploited phalanx rigidity.[25] These cases illustrate causal primacy of formation integrity, weapon length differentials, and targeted force application over sheer numbers.Weaknesses and Tactical Limitations

Vulnerabilities to Flanking and Terrain

The phalanx's design, featuring interlocking shields primarily oriented forward and to the right for mutual protection, left its flanks and rear exposed to enemy assault, as individual hoplites lacked effective shielding on their left sides or behind. This inherent rigidity made rapid wheeling or redeployment difficult, requiring auxiliary cavalry or skirmishers to screen the wings; failure to secure these exposed sectors often resulted in catastrophic envelopment once adversaries achieved superior positioning.[75][76][15] At the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC, the Spartan phalanx succumbed to such a maneuver when Epaminondas concentrated Theban forces on the left to overlap and envelop the enemy right flank, exploiting the Spartans' extended line and leading to their rout despite initial parity in the center. Similarly, in the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, Macedonian cavalry under Philip II outmaneuvered the Greek allied flanks, breaking the cohesion of the hoplite lines and securing victory through combined-arms encirclement.[27][4] The formation's dependence on disciplined, shoulder-to-shoulder alignment rendered it ill-suited to irregular terrain, where elevation changes, rocks, or vegetation disrupted spacing and spear alignment, creating exploitable gaps for lighter troops or individual duels unfavorable to heavily armored hoplites. Flat, open plains thus optimized phalangite effectiveness by enabling sustained frontal pressure without dispersal, while constrained landscapes like hillsides or passes invited disorder and diminished the mutual support integral to the tactic.[77][78] In the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC, hilly ground fragmented the Macedonian phalanx's advance, allowing Roman maniples to infiltrate and attack the flanks piecemeal before the sarissa-bearers could fully form up. At Pydna in 168 BC, uneven terrain during the phalanx's downhill charge against legionaries caused spears to tangle and lines to bunch, enabling Romans to wedge into vulnerabilities and dismantle the formation from the sides.[25][79]Logistical and Adaptability Constraints

The heavy panoply worn by hoplites, weighing approximately 70 pounds including bronze armor, large aspis shield, spear, and secondary weapons, imposed severe physical burdens that restricted daily march distances to around 15-20 kilometers and fatigued troops, particularly without adequate attendants or pack animals for all but essential baggage.[80] This equipment self-reliance, common among citizen-soldiers who purchased their own gear at costs exceeding 100 drachmas, limited scalability for large forces and complicated maintenance during campaigns, as repairs or replacements depended on local forges or carried spares.[80] Transport logistics further strained operations, with reliance on personal loads, occasional carts, mules, or helot bearers for Sparta, but minimal state-provided wagons, exposing armies to overload and slowed advances vulnerable to ambushes on baggage trains.[80] Campaign durations were constrained by these factors and the agrarian economy, typically spanning 15-40 days to align with harvest seasons, as extended absences risked farm neglect and domestic unrest; Spartan invasions of Attica, for instance, routinely concluded upon supply exhaustion after such periods.[80] Supply chains emphasized foraging over organized provisioning, with hoplites carrying initial rations and purchasing or seizing food locally, rendering forces susceptible to enemy scorched-earth policies, cavalry raids on foragers, or water shortages that dictated routes and halts, as seen in Athenian setbacks at Syracuse where disruptions halved effective strength.[80] Rare state depots or convoys, like those for Agesilaus carrying six months' provisions, proved exceptional and logistically intensive, underscoring the phalanx's dependence on proximity to allied territories for sustainability.[80] Adaptability suffered from the formation's inherent rigidity, demanding flat, open plains for maintaining shoulder-to-shoulder files 8-16 deep; rocky, wooded, or hilly terrain fractured cohesion, exposing gaps exploitable by lighter troops and negating the phalanx's massed thrust.[4] Maneuvering from march column to battle line required precise timing and drill, often consuming 30-60 minutes under ideal conditions, with risks of disorder from minor hesitations or flank exposures during wheeling or oblique advances, as evidenced in Xenophon's accounts of Theban tactical shifts straining traditional alignments.[25] This inflexibility hindered responses to skirmishers, cavalry outflanking, or rapid enemy repositioning without dedicated light infantry screens, confining the phalanx to decisive pitched battles rather than pursuits, sieges, or irregular warfare.[4]Historical Failures and Counterexamples

In the Battle of Lechaeum in 390 BC, a force of approximately 600 Spartan hoplites, returning from Corinth in a loose column rather than a tight phalanx formation, was ambushed and decisively defeated by Athenian peltasts under Iphicrates. The light infantry employed hit-and-run tactics with javelin volleys, inflicting over 250 casualties on the Spartans while suffering minimal losses themselves, demonstrating the phalanx's vulnerability to mobile skirmishers when cohesion was disrupted during pursuit or redeployment.[81][82] The Macedonian phalanx under Philip V suffered a critical defeat at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC against Roman legions led by Titus Quinctius Flamininus. Hilly terrain prevented the Macedonians from deploying their sarissa-armed phalanx in a continuous line, forcing advance in fragmented columns; Roman maniples exploited this by occupying higher ground and launching a flanking attack on the exposed Macedonian right, where the phalanx's inability to pivot quickly led to its rout, with thousands killed or captured.[83] At the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC, King Perseus's phalanx of around 29,000 pikemen initially overpowered the Roman front lines under Lucius Aemilius Paullus, but rough, uneven ground caused gaps in the interlocking sarissas as the formation advanced. Roman velites and legionaries, armed with short swords suited for close-quarters exploitation, penetrated these breaches, shattering the phalanx's cohesion and causing a panicked collapse; Macedonian cavalry's failure to support the infantry exacerbated the rout, resulting in over 20,000 Macedonian casualties.[84] These engagements illustrate the phalanx's systemic limitations against forces emphasizing maneuverability, as its rigid structure, optimized for frontal pushes on flat terrain, faltered when flanks were turned or internal discipline broke under environmental pressures.[4]Decline and Post-Classical Legacy

Factors in Classical Obsolescence