Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

CSS Muscogee

View on Wikipedia

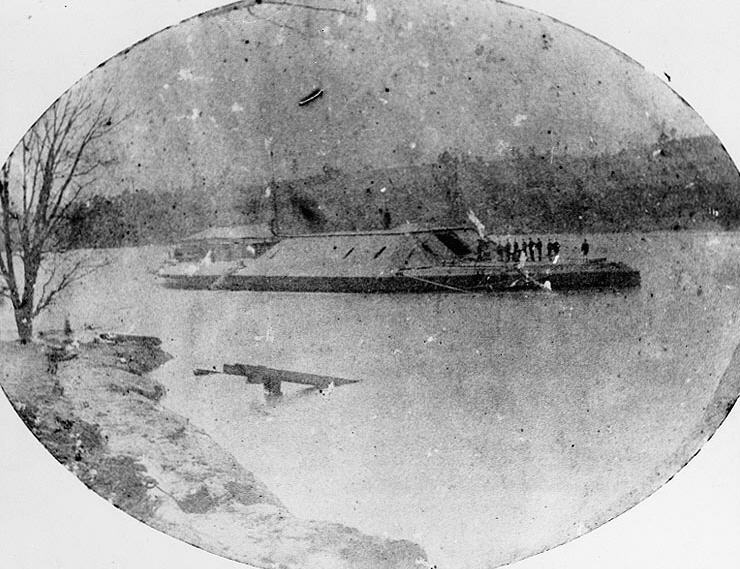

The incomplete CSS Jackson on the Chattahoochee River, shortly after December 22, 1864

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Muscogee |

| Namesake | Muscogee people |

| Builder | Columbus Navy Yard, Columbus, Georgia |

| Laid down | 1862 |

| Launched | December 22, 1864 |

| Renamed | Jackson, sometime in 1864 |

| Fate | Burned, April 17, 1865 |

| Status | Wreck salvaged, 1962–1963; on display at the National Civil War Naval Museum, Columbus, Georgia |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Casemate ironclad |

| Tonnage | 1,250 tons |

| Length | 223 ft 6 in (68.1 m) |

| Beam | 59 ft (18 m) |

| Draft | 8 ft (2.4 m) |

| Installed power | 4 × boilers |

| Propulsion | 2 × propellers; 2 × direct-acting steam engines |

| Armament |

|

| Armor | Casemate: 4 in (102 mm) |

CSS Muscogee and Chattahoochee | |

| NRHP reference No. | 70000212 |

| Added to NRHP | May 13, 1970 |

CSS Muscogee was an casemate ironclad built in Columbus, Georgia for the Confederate States Navy during the American Civil War. Her original paddle configuration was judged a failure when she could not be launched on the first attempt in 1864. She had to be rebuilt to use dual propeller propulsion. Later renamed CSS Jackson and armed with four 7-inch (178 mm) and two 6.4-inch (163 mm) cannons. She was captured while still fitting out and was set ablaze by Union troops in April 1865. Her wreck was salvaged in 1962–1963 and turned over to the National Civil War Naval Museum in Columbus for display. The ironclad's remains were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.

Background and description

[edit]Muscogee was originally built as a sister ship to the casemate ironclad paddle steamer CSS Missouri, to a rough design by the Chief Naval Constructor, John L. Porter, as a sternwheel-powered ironclad. She proved to be too heavy to be launched on January 1, 1864, and had to be reconstructed and lengthened to a modified CSS Albemarle-class design, based on Porter's advice during his visit to the ironclad on January 23.[1][2][3]

As part of the reconstruction, the ironclad was lengthened to 223 feet 6 inches (68.1 m) overall after a new fantail was built on the stern. She had a beam of 59 feet (18 m) and a draft of 8 feet (2.4 m).[3] The removal of her sternwheel allowed her casemate to be shortened by 54 feet (16.5 m), which saved a considerable amount of weight.[2] The ironclad had a gross register tonnage of 1,250 tons.[3]

As originally designed, Muscogee was propelled by a sternwheel that was partially enclosed by a recess at the aft end of the casemate; the upper portion of the paddle wheel protruded above the casemate and would have been exposed to enemy fire. The sternwheel was probably powered by a pair of inclined two-cylinder direct-acting steam engines taken from the steamboat Time using steam provided by four return-flue boilers to the engines. As part of her reconstruction, Time's engines were replaced by a pair of single-cylinder, horizontal direct-acting steam engines from the adjacent Columbus Naval Iron Works, each of which drove a single 7-foot-6-inch (2.3 m) propeller; the original boilers appear to have been retained.[4]

Muscogee's casemate was built with ten gun ports, two each at the bow and stern and three on the broadside. The ship was armed with four 7-inch (178 mm) and two 6.4-inch (163 mm) Brooke rifles. The fore and aft cannons were on pivot gun mounts. The 7-inch guns weighed about 15,300 pounds (6,900 kg) and fired 110-pound (50 kg) shells. The equivalent statistics for the 6.4-inch gun were 10,700 pounds (4,900 kg) with 95-pound (43 kg) shells.[5] The casemate was protected by 4 inches (102 mm) of wrought-iron armor,[3] and the armor plates on the deck and sides of the fantail were 2 inches (51 mm) thick.[2]

History

[edit]

Muscogee was laid down during 1862 at the Columbus Naval Yard at Columbus, Georgia, on the banks of the Chattahoochee River.[3] The first attempt to launch her failed on January 1, 1864, despite the high water on the river and the assistance of the steamboat Mariana. Porter came down afterwards to examine the ironclad and recommended that she be rebuilt with screw propulsion rather than the sternwheel. She was finally launched on December 22, having been renamed Jackson at some point during the year.[2] A shortage of iron plate greatly hindered the ironclad's completion.[6]

On April 17, 1865, after the Union's Wilson's Raiders captured the city during the Battle of Columbus, Georgia, Jackson was set ablaze by Union troops while still fitting out and had her moorings cut. The ship drifted downriver some 30 miles (48 km) and ran aground on a sandbar. She was not thought to be worth salvaging because of the fire damage, but the Army Corps of Engineers dredged around her wreck in 1910 and salvaged her machinery.[7] A Union cavalry officer's report of the ironclad's condition at the time of her capture said that she had four cannon aboard and had a solid oak ram 15 feet (4.6 m) deep. The only detail about her armor that he recorded was that it curved over the edge of the deck and extended below the waterline.[8]

Recovery

[edit]CSS Jackson's remains were raised in two pieces; the 106-foot (32.3 m) stern section in 1962 and the 74-foot (22.6 m) bow section the following year. They were then placed on exhibit at the National Civil War Naval Museum in Columbus.[9] A thick metal white frame outline, indicating the various dimensions of Jackson's original fore and aft deck arrangements and armored casemate, is now erected directly above the hull's wooden remains to simulate for visitors the ironclad's original size and shapes.[10] The ship's fantail, which was stored outside in a pole barn, was partially destroyed in a fire on 1 June 2020.[2]

The ironclad was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 13, 1970.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Bisbee, pp. 162, 176; Holcombe, p. 213

- ^ a b c d e "Save the Fantail". National Civil War Naval Museum. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Silverstone, p. 153

- ^ Bisbee, pp. 13–14, 18, 176

- ^ Silverstone, p. xx

- ^ Canney, p. 68

- ^ Bisbee, p. 177

- ^ Canney, p. 69

- ^ Vance, Elizabeth; Voreis, Sarah (16 April 2013). "Civil War Naval Museum". Chattahoochee Heritage Project. Auburn University School of Communication. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ "CSS Jackson". National Civil War Naval Museum. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ "C.S.S. Muscogee and Chattahoochee (gunboats)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bisbee, Saxon T. (2018). Engines of Rebellion: Confederate Ironclads and Steam Engineering in the American Civil War. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-81731-986-1.

- Canney, Donald L. (2015). The Confederate Steam Navy 1861–1865. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7643-4824-2.

- Holcombe, Robert (1988). "Question 17/86". Warship International. XXV (2): 213–214. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (2006). Civil War Navies 1855–1883. The U.S. Navy Warship Series. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97870-X.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Still, William N. Jr. (1985) [1971]. Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Armorclads. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-454-3.

CSS Muscogee

View on GrokipediaDesign and Construction

Specifications and Armament

The CSS Muscogee was constructed as a casemate ironclad ram optimized for riverine operations on the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola rivers, featuring a low-profile hull with sloped casemate armor to deflect projectiles. Her dimensions included a length of 172 feet, a beam of 29 feet, and a depth of 6 feet, with a shallow draft of approximately 8 feet to navigate inland waterways. The armor plating, produced at local Georgia ironworks using welded railroad T-rails, measured 4 inches thick on the sloped casemate sides, providing protection against naval gunfire while minimizing weight.[5] Propulsion was provided by two horizontal, non-condensing steam engines with 20-inch diameter cylinders, driving a central paddle wheel suited to shallow, obstructed rivers; this configuration prioritized maneuverability over open-water speed, with estimated output in the range of 400-600 horsepower based on comparable Confederate designs.| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Length | 172 feet |

| Beam | 29 feet |

| Depth | 6 feet |

| Draft | 8 feet |

| Armor | 4-inch sloped casemate (railroad iron) |

| Propulsion | 2 horizontal steam engines, central paddle wheel |