Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

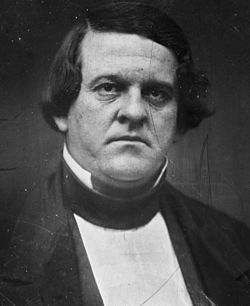

Howell Cobb

View on Wikipedia

Howell Cobb (September 7, 1815 – October 9, 1868) was an American and later Confederate political figure. A southern Democrat, Cobb was a five-term member of the United States House of Representatives and the speaker of the House from 1849 to 1851. He also served as the 40th governor of Georgia (1851–1853) and as a secretary of the treasury under President James Buchanan (1857–1860).

Key Information

Cobb is, however, best known as one of the founders of the Confederacy, having served as the President of the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States where delegates of the Southern slave states declared that they had seceded from the United States and created the Confederate States of America.

Early life and education

[edit]Born in Jefferson County, Georgia in 1815, son of Sarah (née Rootes) and John A. Cobb.[c] Cobb was of Welsh American ancestry.[2] He was raised in Athens and attended the University of Georgia, where he was a member of the Phi Kappa Literary Society. He was admitted to the bar in 1836 and became solicitor general of the western judicial circuit of Georgia.[3]

Cobb was a presidential elector in the 1836 presidential election.[4]

He married Mary Ann Lamar on May 26, 1835. She was a daughter of Colonel Zachariah Lamar, of Milledgeville, from a prominent family with broad connections in the South.[5] Her relatives include Texas President Mirabeau B. Lamar and Georgia resident Gazaway Bugg Lamar.[citation needed] They would have eleven children, the first in 1838 and the last in 1861. Several did not survive childhood, including their last, a son who was named after Howell's brother, Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb.

Career

[edit]Congressman

[edit]

Cobb was elected as Democrat to the 28th, 29th, 30th and 31st Congresses. He was chairman of the U.S. House Committee on Mileage during the 28th Congress, and Speaker of the United States House of Representatives during the 31st Congress.

He sided with President Andrew Jackson on the question of nullification (i.e. compromising on import tariffs), and was an effective supporter of President James K. Polk's administration during the Mexican–American War. He was an ardent advocate of extending slavery into the territories, but when the Compromise of 1850 had been agreed upon, he became its staunch supporter as a Union Democrat.[3][6] He joined Georgia Whigs Alexander Stephens and Robert Toombs in a statewide campaign to elect delegates to a state convention that overwhelmingly affirmed, in the Georgia Platform, that the state accepted the Compromise as the final resolution to the outstanding slavery issues. On that issue, Cobb was elected governor of Georgia by a large majority.

Speaker of the House

[edit]After 63 ballots,[7] he became Speaker of the House on December 22, 1849, at the age of 34.[8] In 1850—following the July 9 death of Zachary Taylor and the accession of Millard Fillmore to the presidency—Cobb, as Speaker, would have been next in line to the presidency for two days due to the resultant vice presidential vacancy and a president pro tempore of the Senate vacancy, except he did not meet the minimum eligibility for the presidency of being 35 years old. The Senate elected William R. King as president pro tempore on July 11.

Governor of Georgia

[edit]In 1851, Cobb left the House to serve as the Governor of Georgia, holding that post until 1853. He published A Scriptural Examination of the Institution of Slavery in the United States: With its Objects and Purposes in 1856.

Return to Congress and Secretary of the Treasury

[edit]

He was elected to the 34th Congress before being appointed as Secretary of the Treasury in Buchanan's Cabinet. He served for three years, resigning in December 1860. At one time, Cobb was Buchanan's choice for his successor.[9]

A Founder of the Confederacy

[edit]In 1860, Cobb ceased to be a Unionist, and became a leader of the secession movement,[3] not surprising since he once owned 1000 slaves.[10] He was president of a convention of the seceded states that assembled in Montgomery, Alabama, on February 4, 1861. Under Cobb's guidance, the delegates drafted a constitution for the new Confederacy. He served as president of several sessions of the Confederate Provisional Congress, and swore in Jefferson Davis as president of the Confederacy before resigning to join the military when war erupted.[11]

American Civil War

[edit]

Cobb joined the Confederate army and was commissioned as colonel of the 16th Georgia Infantry. He was appointed a brigadier general on February 13, 1862, and assigned command of a brigade in what became the Army of Northern Virginia. Between February and June 1862, he represented the Confederate authorities in negotiations with Union officers for an agreement on the exchange of prisoners of war. His efforts in these discussions contributed to the Dix-Hill Cartel accord reached in July 1862.[12]

Cobb saw combat during the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles. Cobb's brigade played a key role in the fighting during the Battle of South Mountain, especially at Crampton's Gap, where it arrived at a critical time to delay a Union advance through the gap, but at a bloody cost. His men also fought at the subsequent Battle of Antietam.

In October 1862, Cobb was detached from the Army of Northern Virginia and sent to the District of Middle Florida. He was promoted to major general on September 9, 1863, and placed in command of the District of Georgia and Florida. He suggested the construction of a prisoner-of-war camp in southern Georgia, a location thought to be safe from Union incursions. This idea led to the creation of the infamous Andersonville prison.

When William T. Sherman's armies entered Georgia during the 1864 Atlanta campaign and subsequent March to the Sea, Cobb commanded the Georgia Reserve Corps as a general. In the spring of 1865, with the Confederacy clearly waning, he and his troops were sent to Columbus, Georgia to help oppose Wilson's Raid. He led the hopeless Confederate resistance in the Battle of Columbus, Georgia on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1865.

During Sherman's March to the Sea, the army camped one night near Cobb's plantation.[13] When Sherman discovered that the house he planned to stay in for the night belonged to Cobb, whom Sherman described in his Memoirs as "one of the leading rebels of the South, then a general in the Southern army," he dined in Cobb's slave quarters,[14] confiscated Cobb's property and burned the plantation,[15] instructing his subordinates to "spare nothing."[16]

In the closing days of the war, Cobb fruitlessly opposed General Robert E. Lee's eleventh hour proposal to enlist slaves into the Confederate Army. Fearing that such a move would completely discredit the Confederacy's fundamental justification of slavery, that black people were inferior, he said, "You cannot make soldiers of slaves, or slaves of soldiers. The day you make a soldier of them is the beginning of the end of the Revolution. And if slaves seem good soldiers, then our whole theory of slavery is wrong."[3]

Cobb surrendered to the U.S. at Macon, Georgia on April 20, 1865.

Later life and death

[edit]

Following the end of the Civil War, Cobb returned home and resumed his law practice. Despite pressure from his former constituents and soldiers, he refused to make any public remarks on Reconstruction policy until he received a presidential pardon, although he privately opposed the policy. Finally receiving the pardon in early 1868, he began to vigorously oppose the Reconstruction Acts, making a series of speeches that summer that bitterly denounced the policies of Radical Republicans in the U.S. Congress.

That autumn, Cobb vacationed in New York City, and died of a heart attack there. His body was returned to Athens, Georgia, for burial in Oconee Hill Cemetery.[17]

Legacy

[edit]As a former Speaker of the House, his portrait had been on display in the US Capitol. The portrait was removed from public display in the Speaker's Lobby outside the House Chamber after an order issued by the Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi on June 18, 2020, during the George Floyd protests.[18][19]

Cobb family

[edit]The Cobb family included many prominent Georgians from both before and after the Civil War era. Cobb's uncle and namesake, also Howell Cobb, had been a U.S. Congressman from 1807 to 1812, and then served as an officer in the War of 1812.

Cobb's younger brother, Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb, was also a politician and soldier and was killed in the Civil War. Thomas Willis Cobb, a member of the United States Congress and namesake of Georgia's Cobb County, was a cousin. His niece Mildred Lewis "Miss Millie" Rutherford was a prominent educator, white supremacy advocate, and leader in the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Howell Cobb's daughter, Mrs. Alexander S. (Mary Ann Lamar Cobb) Erwin, was responsible for creating the United Daughters of the Confederacy's Southern Cross of Honor in 1899, which was awarded to Confederate Veterans.[20] His son, Andrew J. Cobb, served as a justice of the Georgia Supreme Court.[21]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ multi-ballot election; voting lasted 19 days (The total vacancy was over eight months; Congress simply didn't vote or do any work until December.)

- ^ Not to be confused with Constitutional Union Party of 1860, the Constitutional Union Party in Georgia was a brief merger of the Democratic and Whig state parties.[1]

- ^ John Cobb's brother Henry Cobb was the father of Susan Amanda Cobb first wife of Florida Civil War Governor John Milton.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Murray, Paul (1945). "Party Organization in Georgia Politics 1825–1853". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 29 (4): 206–207. JSTOR 40576991.

- ^ Boykin, Samuel, ed. (1870). A memorial volume of the Hon. Howell Cobb, of Georgia. Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott & Co. p. 14. OCLC 1647859.

- ^ a b c d Chisholm 1911.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. Vol. I. New York, N.Y.: James T. White & Co. 1898. p. 226 – via Google Books.

- ^ Knight, Lucien Lamar (1917). A Standard History of Georgia and Georgians. Vol. 3. Lewis Publishing Co. p. 1339. OCLC 1855247.

- ^ Brooks, R. P. (December 1917). "Howell Cobb and the Crisis of 1850". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 4 (3): 279–298. doi:10.2307/1888593. JSTOR 1888593.

- ^ Jenkins, Jeffery A.; Stewart, Charles Haines (2012). Fighting for the speakership the House and the rise of party government. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9781400845460.

- ^ Hamilton, Holman (2015). Prologue to Conflict : The Crisis and Compromise of 1850. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. p. 42. ISBN 978-0813191362.

- ^ Klein, Philip Shriver (1962). James Buchanan : a biography. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 11.

- ^ Larson, Erik. "A President Called 'Aunt Fancy'". Delanceyplace.com. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- ^ Davis, Ruby Sellers (1962). "Howell Cobb, President of the Provisional Congress of the Confederacy". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 46 (1): 20–33. JSTOR 40578354.

- ^ Official Records. Series II, Vol. 3, pp. 338–340, 812–813, Vol. 4, pp. 31–32, 48.

- ^ Seibert, David. "Howell Cobb Plantation". GeorgiaInfo: an Online Georgia Almanac. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- ^ Hanson, Victor Davis (1999). The Soul of Battle: From Ancient Times to the Present Day, How Three Great Liberators Vanquished Tyranny. New York City: The Free Press. p. 211. ISBN 9780684845029. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ Mitchell, Robert B. (November 2014). "Terrible beyond endurance". America's Civil War. 27 (5): 37. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ Sherman, William Tecumseh (1886). Memoirs of General William T. Sherman. Vol. II. New York: D. A. Appleton and Company. p. 185.

- ^ Reid, R. L. "Howell Cobb". New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Portraits of Confederate House Speakers Removed From Capitol". Slate. June 19, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Snell, Kelsey (June 18, 2020). "Confederate Speaker Portraits To Be Removed From The U.S. Capitol On Juneteenth". NPR. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, David T. (November 30, 2012). "Southern Cross of Honor: Whitehead & Hoag wins contract". Coin World. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ "Judge Cobb Dies Of Heart Attack Following Stroke", The Atlanta Constitution (March 28, 1925), p. 1.

Sources

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cobb, Howell". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 606.

- Eicher, John H.; Eicher, David J. (2001). Civil War High Commands. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Sifakis, Stewart (1988). Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Simpson, John Eddins (1971). "Howell Cobb's Bid for the Presidency in 1860". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 55 (1): 102–113. JSTOR 40579191.

- Simpson, John Eddins (1974). "Prelude to Compromise: Howell Cobb and the House Speakership Battle of 1849". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 58 (4): 389–399. JSTOR 40580047.

- United States Congress. "Howell Cobb (id: C000548)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- US Department of War (1880–1901). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- Warner, Ezra J. (1959). Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 445052.

Further reading

[edit]- Montgomery, Horace (1959). Howell Cobb's Confederate Career. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Confederate Publishing.

- Simpson, John E. (1973). Howell Cobb: the Politics of Ambition. Chicago, Illinois: Adams Press.

External links

[edit]- Howell Cobb entry at the National Governors Association

- Howell Cobb (1815–1868) entry at The Political Graveyard

- Howell Cobb at Find a Grave

- Joseph Emerson Brown letters, W.S. Hoole Special Collections Library, The University of Alabama.

- "The Late Howell Cobb" Archived March 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Southern Recorder, November 10, 1868. Atlanta Historic Newspaper Archive. Digital Library of Georgia

- U.S. Treasury - Biography of Secretary Howell Cobb

- Cobb, Howell. "[Letter] 1858 Jan. 20, Treasury Department [to] J[ames] W[harey] Terrell, Qualla Town [i.e., Quallatown], North Carolina". Southeastern Native American Documents, 1730–1842. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved February 21, 2018.[permanent dead link]

Howell Cobb

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Birth, Family, and Upbringing

Howell Cobb was born on September 7, 1815, at the family's Cherry Hill plantation in Jefferson County, Georgia.[2] He was the eldest son of John Addison Cobb, a planter and Revolutionary War descendant, and Sarah Rootes Cobb, whose family traced roots to early Virginia settlers.[7] The Cobbs operated a substantial agricultural estate reliant on enslaved labor, reflecting the economic structure of rural antebellum Georgia, where cotton and other cash crops dominated production.[8] Cobb's paternal uncle, Howell Cobb (1772–1818), had served as a U.S. congressman from Georgia and owned the Cherry Hill property before his death, leaving the family connected to early American political networks.[1] His younger brother, Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb, later emerged as a Confederate general and legal scholar, underscoring the family's martial and intellectual inclinations amid Southern planter society.[7] Raised initially in the plantation environment of Jefferson County, Cobb experienced the hierarchical social order of slave-based agriculture, which instilled values of agrarian self-reliance and regional loyalty from an early age. Approximately in 1822, his family moved to Athens, Georgia, positioning him nearer to educational opportunities while maintaining ties to rural landownership.[9] This transition exposed him to a blend of frontier planter life and emerging urban influences in the state, shaping his formative years before formal schooling.[2]Education and Entry into Law

Cobb attended the University of Georgia (then known as Franklin College) in Athens, graduating in 1834 with cum laude honors.[10][11] Following his academic completion, he pursued legal studies under established practitioners, reflecting the era's apprenticeship model for bar admission rather than formal graduate programs.[2] Admitted to the Georgia bar in 1836, Cobb promptly commenced his legal practice in Athens, where he handled civil and criminal cases amid a growing regional economy tied to agriculture and emerging commerce.[11][3] His early career demonstrated aptitude in statutory interpretation, as evidenced by his later authorship of influential compilations such as the 1846 Analysis of the Statutes of Georgia, which systematized state laws with practical forms and precedents for attorneys.[12] This work underscored his methodical approach to legal codification, drawing on Georgia's evolving penal and civil codes to aid practitioners navigating inconsistent statutes.[12] Cobb's entry into law coincided with his initial forays into politics, as his courtroom advocacy honed skills in argumentation and public persuasion that propelled his subsequent electoral successes.[5] Despite personal accounts of youthful indiscretions during his university years—marked by a lively temperament that occasionally disrupted studies—his professional debut established him as a capable litigator in Clarke County courts.[13] By the late 1830s, his practice provided financial stability, enabling full commitment to Democratic Party activities without reliance on patronage.[14]Political Ascendancy

Georgia Legislature and Early Congressional Terms

Cobb entered Georgia public service in 1837 when the state legislature elected him solicitor general of the Western Judicial Circuit, a position he held until pursuing national office.[15] In this role, he prosecuted cases across several counties, gaining prominence as a young Democrat committed to Jacksonian principles of limited federal power and states' rights within the Union framework.[3] After an unsuccessful congressional campaign in 1840, Cobb secured nomination from Georgia Democrats in 1842 and won election to the U.S. House of Representatives for the 28th Congress (1843–1845), representing the state at-large.[16] [6] He was reelected to the 29th (1845–1847) and 30th (1847–1849) Congresses, serving Georgia's Sixth District in the latter two terms.[17] As a House member, Cobb championed southern agricultural interests, opposing high protective tariffs that burdened exporters of cotton and other staples.[15] In the 28th Congress, he chaired the Committee on Mileage, overseeing reimbursements for members' travel, a minor but procedural role that highlighted his rising influence among Democrats.[2] Cobb defended slavery as protected by the Constitution and resisted northern antislavery measures, yet prioritized national unity over sectional extremism, breaking from fire-eating southerners who demanded immediate territorial expansion of slavery without compromise.[15] His support for President James K. Polk's Mexican-American War policies, including territorial acquisitions, reflected a pragmatic stance aimed at balancing southern expansionist goals with federal authority.[1] Throughout these terms, Cobb's rhetoric emphasized empirical fidelity to the Union, arguing that secessionist threats undermined southern leverage in Congress and risked economic disruption from disrupted trade.[15] He opposed the Wilmot Proviso's exclusion of slavery from Mexican Cession territories, viewing it as a violation of equal rights for states, but advocated legislative negotiation over disunion.[2] By 1849, his reputation as a conciliator positioned him for higher leadership, culminating in his election as Speaker in the 31st Congress.[2]Speakership of the House (1849–1851)

The 31st United States Congress convened on December 3, 1849, with neither major party holding a clear majority in the House of Representatives, leading to a contentious speakership election that spanned 63 ballots over several weeks.[18] Initial frontrunners included Whig Robert C. Winthrop and Democrat Howell Cobb, but shifting alliances among Democrats, Whigs, and Free Soilers prolonged the deadlock until Cobb emerged as a compromise candidate on December 22, 1849.[18] His selection reflected his reputation as a pro-Union southern Democrat committed to sectional reconciliation amid rising tensions over slavery in the territories acquired from the Mexican-American War.[19] As Speaker, Cobb presided over the House with a focus on maintaining order during heated debates on western expansion and slavery, notably influencing the passage of the Compromise of 1850 through strategic rulings from the chair and private negotiations.[20] The compromise package, introduced by Henry Clay and refined by Stephen Douglas into separate bills, admitted California as a free state, organized the Utah and New Mexico territories under popular sovereignty for slavery decisions, abolished the slave trade in Washington, D.C., and strengthened the Fugitive Slave Act—measures Cobb actively supported to avert disunion.[16] His efforts, including committee assignments and procedural decisions favoring compromise, helped secure House approval of the bills between May and September 1850, despite opposition from both abolitionists and fire-eating secessionists.[20] Cobb's speakership emphasized procedural impartiality while leveraging his influence to prioritize Union-preserving legislation, as evidenced by his role in quelling disruptions and advancing the compromise amid threats of southern withdrawal from Congress.[18] By March 4, 1851, the end of the 31st Congress, the compromise had temporarily eased sectional strife, bolstering Cobb's standing as a moderate voice for national unity, though it failed to resolve underlying conflicts over slavery's expansion.[16] He declined re-election to the speakership in the subsequent Congress to pursue the Georgia governorship, marking the conclusion of his House leadership amid ongoing partisan realignments.[20]Governorship of Georgia (1851–1853)

Howell Cobb was elected governor of Georgia on October 6, 1851, as the nominee of the newly formed Constitutional Union Party, a coalition of Union Democrats and Whigs supporting the Compromise of 1850.[15] He defeated the Resistance Party candidate Charles J. McDonald, who opposed the compromise on states' rights grounds. Cobb's victory reflected the popularity of his moderate Unionist stance, which sought to preserve the federal union while safeguarding Southern interests, including slavery, against both northern abolitionism and southern disunionism.[15] Cobb was inaugurated on November 5, 1851, serving until October 9, 1853.[3] During his tenure, he advocated pro-Union policies that solidified Georgia's acceptance of the Compromise of 1850, emphasizing constitutional adherence over secessionist threats.[15] Domestically, Cobb proposed leasing the state-owned Western and Atlantic Railroad to private operators to generate revenue for public needs.[3] He supported economic provisions for railroads, schools, and care for the mentally ill through funding for educational and philanthropic organizations.[3] Cobb also pushed for administrative reforms, including holding Supreme Court sessions in the state capital, electing a state attorney general, and resuming annual legislative sessions.[3] One concrete achievement was securing $1,000 in annual funding for the state library.[3] His coalition faced challenges in 1852 when Whig leaders such as Alexander Stephens and Robert Toombs refused to merge with the national Democratic Party, contributing to its eventual dissolution.[15] Cobb's governorship maintained stability amid national sectional tensions by prioritizing Union preservation and internal development.[15]Federal Service and Sectional Tensions

Return to Congress (1855–1857)

Following his single term as governor of Georgia, Howell Cobb was elected to represent Georgia's Sixth Congressional District in the Thirty-fourth United States Congress, serving from March 4, 1855, to March 3, 1857.[2] As a Southern Democrat, Cobb resumed his advocacy for policies preserving the Union through compromise while protecting slaveholders' rights to extend slavery into federal territories under the principle of popular sovereignty established by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.[15] This stance positioned him against both Northern abolitionists and radical Southern fire-eaters who sought guaranteed slavery expansion without territorial self-determination.[5] In the 34th Congress, Cobb participated in heated debates over the organization of Kansas Territory, where violence between pro- and anti-slavery settlers—known as "Bleeding Kansas"—highlighted the Act's destabilizing effects. He argued that Kansas and Nebraska residents possessed the sovereign right to decide slavery's status for themselves, rejecting federal imposition of either free or slave institutions as a violation of democratic self-rule and constitutional equality between sections.[21] Cobb delivered speeches, including one in December 1855 reaffirming the Democratic platform's commitment to non-interference with slavery where it existed and territorial autonomy, and addressed New England audiences to defend these principles against growing Republican opposition.[5] His Remarks of Mr. Cobb of Georgia also addressed House procedural matters amid factional gridlock involving Know-Nothings and anti-Nebraska Democrats.[5] The caning of Senator Charles Sumner by Representative Preston Brooks in May 1856, a direct response to Sumner's "Crime Against Kansas" speech vilifying Southerners and slavery, drew Cobb into further sectional controversy. As part of the minority report from the Select Committee investigating the assault, Cobb defended Brooks's actions as a justifiable defense of honor against Sumner's inflammatory rhetoric, which equated slavery defenders to barbarians and threatened Southern institutions.[22] In 1856, Cobb published A Scriptural Examination of the Institution of Slavery in the United States, contending biblically that slavery aligned with divine order and was not inherently sinful, countering abolitionist moral arguments.[5] Cobb's congressional term coincided with the 1856 presidential election, during which he actively campaigned for Democratic nominee James Buchanan, traveling to Northern and Western states to argue for compromise and warn against Republican threats to slavery.[15] His efforts helped secure Buchanan's victory, paving the way for Cobb's appointment as Secretary of the Treasury in 1857, after which he left Congress. Throughout, Cobb prioritized Union preservation via balanced sectional interests, though events in Kansas underscored the fragility of such compromises amid irreconcilable views on slavery's expansion.[2][5]Secretary of the Treasury (1857–1860)

Howell Cobb was appointed Secretary of the Treasury by President James Buchanan on March 6, 1857, becoming the 22nd individual to hold the position.[4] His selection rewarded Cobb's support for Buchanan's presidential campaign, reflecting the administration's effort to balance Southern interests in the cabinet.[23] During his tenure, Cobb focused primarily on fiscal management amid economic challenges and persistent sectional disputes over slavery expansion.[16] The Panic of 1857, triggered by a stock market crash in August of that year, dominated Cobb's early efforts.[24] He attributed monetary tightness to the Treasury's accumulating surplus and advocated releasing government-held gold into circulation to alleviate liquidity strains.[4] Cobb directed the deposit of substantial gold reserves on the open market and facilitated payments to creditors using specie from federal vaults, measures intended to stabilize banking and commerce without direct federal intervention.[24] These actions aligned with his predecessor's views but faced criticism for potentially exacerbating speculation, though they provided short-term relief amid widespread bank failures and unemployment.[16] On fiscal policy, Cobb urged Congress to increase tariffs to generate revenue and reduce the Treasury surplus, warning that low duties hindered recovery.[4] Lawmakers delayed action until the Tariff of 1860, leaving the department with depleted coffers by the end of his term.[4] As a Southern Democrat, Cobb also navigated administration responses to territorial slavery questions, endorsing compromise positions like those in the English Bill of 1858, which aimed to admit Kansas under the Lecompton Constitution despite irregularities.[15] His public stance emphasized constitutional protections for slavery while advocating Union preservation through moderation.[15] In 1860, Cobb sought the Democratic presidential nomination but failed amid party fractures over slavery's territorial extension.[16] Following Abraham Lincoln's election on November 6, Cobb resigned on December 8, citing irreconcilable differences with the incoming administration's perceived hostility to Southern rights.[25] His departure marked a pivot toward secession advocacy, ending a tenure characterized by pragmatic economic stewardship overshadowed by mounting national divisions.[26]Commitment to Southern Independence

Evolution of Views on Secession

Cobb's early political career in the 1840s emphasized Union preservation, rejecting secession as an unconstitutional remedy absent a clear violation of the federal compact by the North. As a Democratic congressman, he opposed John C. Calhoun's 1849 Southern Address advocating disunion over slavery's territorial expansion, instead favoring legislative compromises to protect Southern interests within the existing framework.[5] During the 1850 sectional crisis, serving as Speaker of the House, Cobb championed the Compromise of 1850 as a "finality" measure to quell secessionist fervor, arguing that dissolution of the government established by the framers lacked justification without Northern aggression against slavery. In Georgia, he aligned with moderates Alexander Stephens and Robert Toombs to draft the Georgia Platform on December 10, 1850, pledging fidelity to the Union so long as the compromises— including the Fugitive Slave Act and organization of territorial governments without slavery restrictions in California—were upheld as permanent adjustments to sectional disputes. This stance secured overwhelming pro-Union electoral victories in Georgia, averting immediate disunion.[5] Into the mid-1850s, as governor and later congressman, Cobb sustained his unionism by endorsing the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 for its popular sovereignty provisions, which deferred slavery decisions to local voters, and by co-founding the Constitutional Union Party in 1859 to rally against both Republican abolitionism and Southern fire-eaters. Yet, escalating Northern resistance—manifest in the Republican Party's rise and events like the 1859 John Brown raid—eroded his faith in compromise. The pivotal shift occurred with Abraham Lincoln's election on November 6, 1860, which Cobb interpreted as a sectional triumph endangering slavery and states' rights, nullifying the Union's reciprocal protections. Resigning as Treasury Secretary on December 8, 1860, he publicly affirmed Georgia's "right or duty to secede," urging immediate action to form a Southern confederacy rather than await coercion.[4][15][5]Presidency of the Provisional Confederate Congress

Following Georgia's secession from the Union on January 19, 1861, Howell Cobb was elected president of the Provisional Confederate Congress by acclamation on February 4, 1861, at the State Capitol in Montgomery, Alabama, where the congress convened its first session.[27] In this presiding role, Cobb oversaw the legislative body responsible for organizing the provisional government of the seceded states, which initially comprised delegates from South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas.[28] He assumed the chair immediately upon election and took an oath to support the provisional constitution on February 9, 1861.[27] Under Cobb's leadership, the congress achieved several foundational acts during its first session from February 4 to March 16, 1861, including the election of Jefferson Davis as provisional president and Alexander H. Stephens as vice president on February 9, 1861, after Cobb himself had been considered for the position but faced opposition from more radical southern delegates.[15] [27] Cobb administered the oaths of office to Davis and Stephens on February 18, 1861, in Montgomery.[16] The body adopted a provisional constitution on March 11, 1861, which established a temporary government to last one year or until a permanent frame was ratified, while also authorizing executive departments, a provisional army, and initial fiscal measures such as tariffs to fund operations.[29] Subsequent sessions under Cobb's presidency included the second from April 29 to May 21, 1861, in Montgomery, where military organization advanced amid escalating tensions, and later sessions after the capital relocated to Richmond, Virginia, following Virginia's secession: the third from July 20 to August 31, 1861, a brief one on September 3, 1861, and the fifth from November 18, 1861, to February 17, 1862.[27] These addressed wartime preparations, including fortifications and diplomacy, as the Confederacy expanded to include additional states like Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina.[28] The Provisional Congress adjourned sine die on February 17, 1862, yielding to the first permanent Confederate Congress, marking the end of Cobb's term; he then transitioned to military service as a colonel in the Confederate Army.[27] [15]Civil War Military Service

Commission and Commands

Following Georgia's secession from the Union in January 1861, Howell Cobb resigned his congressional seat and entered Confederate military service as colonel of the 16th Georgia Infantry Regiment on July 15, 1861.[30] He led the regiment in early operations before receiving promotion to brigadier general in the Confederate States Army on February 13, 1862.[31] In this capacity, Cobb was assigned command of a brigade in Lafayette McLaws's division within the Army of Northern Virginia, participating in the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles around Richmond in 1862.[32] In October 1862, Cobb was transferred from field command in Virginia to the District of Middle Florida, where he oversaw defenses against potential Union incursions into the region.[15] Promoted to major general on September 9, 1863, he assumed command of Georgia state troops and the District of Georgia and Florida, responsibilities that encompassed coordinating militia forces, fortifications, and conscription efforts to bolster Confederate defenses in the southeastern theater.[33] [32] These commands reflected his transition from frontline brigade leadership to higher-level administrative and territorial oversight amid escalating Union pressures.[15] Cobb retained authority over these districts until surrendering his forces to Union troops in Macon, Georgia, on April 20, 1865.[15]