Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

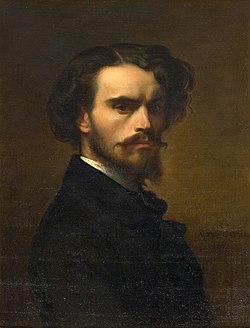

Alexandre Cabanel

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2013) |

Alexandre Cabanel (French: [alɛksɑ̃dʁ(ə) kabanɛl]; 28 September 1823 – 23 January 1889) was a French painter. He painted historical, classical and religious subjects in the academic style.[1] He was also well known as a portrait painter. He was Napoleon III's preferred painter[2] and, with Gérôme and Meissonier, was one of "the three most successful artists of the Second Empire."[3]

Key Information

Career

[edit]Cabanel was the son of a modest carpenter, and he began his apprenticeship at the Montpellier School of Fine Arts in the class of Charles Matet, curator of the Musée Fabre. Equipped with a scholarship, he moved to Paris in 1839.

Cabanel entered the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris at the age of seventeen, in 1840, where he studied with François-Édouard Picot.

After two failures, with the paintings Cincinnatus receiving the ambassadors of Rome, in 1843, and Christ in the Garden of Olives, in 1844, he won the Prix de Rome scholarship, in 1845 at the age of 22.[4] He would be a resident of the Villa Medici until 1850.

Cabanel was both a history painter and a genre painter, and he evolved over the years towards romantic themes, like Albaydé (1848), inspired by Les Orientales, by Victor Hugo (1829).

He received the insignia of knight of the Legion of Honor, in 1855.

Also in 1855, he married Marie-Clémentine Legrand, with whom he had three children. Legrand and two of the children died in 1867. He remarried in 1869, but his second wife also died just four years later.[5]

He gained more recognition with The Birth of Venus, exhibited at the Salon of 1863, and which was immediately purchased by Napoleon III for his personal collection. The acclaimed painting entered the Luxembourg Museum, in 1881, and is now held at the Musée d'Orsay, in Paris. He signed a contract with the Goupil house for the marketing of engraved reproductions of this painting. There is a smaller replica, painted in 1875 for a banker, John Wolf, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York City. It was offered to the museum by Wolf in 1893. The classical composition embodies ideals of Academic art: a mythological subject, graceful modeling, silky brushwork, and perfected forms. This style was perennially popular with collectors, even as when it was challenged by artists seeking a more realistic approach, such as Gustave Courbet. He was also criticized by writers and critics like Émile Zola and Joris-Karl Huysmans, who were more open to the modern artistic tendencies.

French Academy of Fine Arts

[edit]Cabanel was elected a member of the Academy of Fine Arts in the 10th chair, in 1863. He was appointed professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1864, where he taught until his death.[6] He was in the same year promoted to the rank of officer of the Legion of Honor.

Between 1868 and 1888, he was a member of the Salon jury seventeen times: "He was elected regularly to the Salon jury and his pupils could be counted by the hundred at the Salons. Through them, Cabanel did more than any other artist of his generation to form the character of the belle époque French painting".[7] His refusal together with William-Adolphe Bouguereau to allow the impressionist painter Édouard Manet, and other painters, to exhibit their work in the Salon of 1863 led to the establishment of the Salon des Refusés by the French government. Cabanel won the Great Medal of Honour at the Salons of 1865, 1867, and 1878.

The Salon jury was not liberal, they accepted and promoted only academic-style paintings with the intention of securing this art in the memory of the public for eternity.[8] Cabanel intervened in 1881 during the presentation of Pertuiset, Le chasseur de lions, by Édouard Manet, and defended it by saying: "Gentlemen, there is not one among us who is capable of doing a head like that in the open air!". At the Universal Exhibition of 1867, Cabanel was awarded the Knight's Cross of the First Class of the Order of Merit of Saint Michael of Bavaria, following his Paradise Lost, commissioned for the Maximilianeum, in Munich, by Ludwig II of Bavaria. He was promoted to the rank of Commander of the Legion of Honor in 1884, and was elected associate of the Royal Academy of Belgium on 6 January 1887.

He died on 24 January 1889, in his hotel at 14 rue Alfred de Vigny, in the 8th arrondissement of Paris. His funeral took place in Paris, on 26 January 1889, in the Saint-Philippe du Roule church, then his body was transported to Montpellier, where it was buried in the Saint-Lazare on 28 January 1889. A monument was erected to him in 1892 by the architect Jean Camille Formigé, decorated with a marble bust by Paul Dubois and a sculpture, Regret, by Antonin Mercié.

Pupils

[edit]

His pupils included:

- Rodolfo Amoedo

- Joseph Aubert

- Henry Bacon

- George Randolph Barse

- Alexandre Jean-Baptiste Brun

- Jean-Eugène Buland

- Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant

- Vlaho Bukovac

- Gaston Bussière

- Louis Capdevielle

- Eugène Carrière

- Eugène Chigot

- Jacqueline Comerre-Paton

- Fernand Cormon

- Pierre Auguste Cot

- Kenyon Cox

- Édouard Debat-Ponsan

- Gabriel-Charles Deneux

- Louis Deschamps (painter)

- Émile Friant

- François Guiguet

- Jules Bastien-Lepage

- François Flameng

- Charles Fouqueray

- Frank Fowler

- Henri Gervex

- Charles Lucien Léandre

- Max Leenhardt

- Henri Le Sidaner

- Aristide Maillol

- Édouard-Antoine Marsal

- João Marques de Oliveira

- Jan Monchablon

- Georges Moreau de Tours

- Henri-Georges Morisset

- Henri Pinta

- Henri Regnault

- Iakovos Rizos

- Louis Royer

- Jean-Jacques Scherrer

- António Silva Porto

- Edward Stott

- Joseph-Noël Sylvestre

- Solomon Joseph Solomon

- Paul Tavernier

- Almeida Júnior

- Étienne Terrus

- Adolphe Willette

Selected works

[edit]

- The Fallen Angel (L'ange déchu, 1847), Musée Fabre, Montpellier

- Aglaé and Boniface (Aglaé et Boniface, 1857), The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio US

- The Birth of Venus (La naissance de Vénus, 1863), Musée d'Orsay, Paris

- Napoleon III (1865), Musée national du château de Compiègne, Écouen, France

- The Death of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta (La mort de Francesca de Rimini et de Paolo Malatesta, 1870), Musée d'Orsay, Paris

- Portrait de la comtesse de Keller (1873), Musée d'Orsay, Paris

- Thamar (1875)

- Phèdre (1880), Musée Fabre, Montpellier

- Ruth glanant dans les champs de Booz (1886), Musée Garinet, Châlons-en-Champagne

- Portrait de Mary Victoria Leiter (1887), Kedleston Hall, England

- Cleopatra Testing Poisons on Condemned Prisoners (Cléopâtre essayant des poisons sur des condamnés à mort, 1887), Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp

- Portrait of Napoleon III (Cabanel)

Gallery

[edit]-

The Fallen Angel (1847)

-

Albaydé (1848)

-

The Death of Moses (1850)

-

Nymph and Satyr (1860)

-

Portrait of Napoleon III (c. 1865)

-

The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Paradise (1867)

-

The death of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta (1870)

-

Portrait of Cornelia Lyman Warren (1871)

-

Portrait of Countess Elizabeth Vorontsova-Dashkova (1873)

-

Pandora (1873), The Walters Art Museum

-

Echo (1874)

-

Thamar (1875)

-

Harmonie (1877)

-

The daughter of Jephthah (1879)

-

Phaedra (1880)

-

Ophelia (1883)

-

Le Titan (1884)

References

[edit]- ^ Kidd, Rebecca (2019). Alexandre Cabanel's St. Monica in a Landscape: A Departure from Iconographic Traditions (Thesis).

- ^ Diccionario Enciclopedico Salvat, Barcelona, 1982.

- ^ Wright, Barbara. Eugéne Fromentin: A Life in Art and Letters, Bern: Peter Lang, 2000, p. 432.

- ^ Facos, Michelle (2011). An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art. Routledge. p. 282.

- ^ "Alexandre Cabanel". Cirtemmysart. 15 June 2022.

- ^ van Hook, Bailey (1996). Angels of Art: Women and Art in American Society, 1876–1914. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 28.

- ^ Dictionary of Art (1996) vol. 5, pp. 341-344

- ^ John Nici (2015). Famous Works of Art And How They Got That Way. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 153. ISBN 9798765168752.

External links

[edit]Alexandre Cabanel

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Birth and Family Background

Alexandre Cabanel was born on September 28, 1823, in Montpellier, France, into a modest working-class family.[4] His father, a carpenter, provided for the household amid limited financial resources, as the family navigated the economic realities of southern France in the early 19th century.[5] As the youngest of several children, Cabanel grew up in an environment where artistic pursuits were not immediately accessible, yet his innate talent emerged early.[6] From a young age, Cabanel displayed a precocious aptitude for drawing, creating initial sketches inspired by the vibrant local art scene in Montpellier, which included access to the renowned Musée Fabre and its collection of classical works.[1] Despite the family's economic constraints, his parents recognized and supported his potential, encouraging his initial explorations in art rather than directing him toward a trade like carpentry.[4] This familial backing, though challenged by their modest circumstances, allowed Cabanel to pursue informal studies and lay the groundwork for his future development.[2] Cabanel's early life unfolded in the socio-economic context of post-Napoleonic France during the Bourbon Restoration, a period marked by political stabilization after the Napoleonic Wars but persistent hardships for the working classes, including rural and artisanal families like his own.[7] Economic recovery was uneven, with inflation and land reforms disrupting traditional livelihoods, yet the era's emphasis on merit-based institutions in the arts fostered aspirations among talented individuals from humble backgrounds to achieve social mobility through exceptional skill. In Montpellier, a regional hub with growing cultural institutions, this environment provided fertile ground for young artists like Cabanel to envision paths beyond their class origins.[1]Artistic Training in Montpellier and Paris

Cabanel began his formal artistic training in his hometown of Montpellier at the municipal drawing school, associated with the École des Beaux-Arts de Montpellier, where he studied under Charles Matet, the school's director and curator of the Musée Fabre.[3][1] Admitted around 1833 at the age of ten, his early aptitude was evident in self-portraits dated 1836, demonstrating a precocious command of form and expression.[1] Matet's guidance emphasized classical drawing techniques, laying the foundation for Cabanel's academic approach, and by 1836, the artist's progress earned him a municipal scholarship recommended by his teacher.[6] Encouraged by this support and his family's modest circumstances as a carpenter's son, Cabanel relocated to Paris in 1839 to pursue advanced study.[3] The following year, at age seventeen, he gained admission to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, where he trained in the atelier of François-Édouard Picot, a neoclassical painter known for historical subjects.[1][8] Under Picot's rigorous instruction, which stressed anatomical precision and compositional harmony inspired by Raphael and antiquity, Cabanel honed his skills through life drawing and historical compositions, preparing for competitive examinations.[9] In 1845, Cabanel achieved a breakthrough by placing second in the Prix de Rome competition with his painting Jesus in the Praetorium, a dramatic depiction of Christ's trial that showcased his mastery of emotional intensity and chiaroscuro.[1][8] Although ranked behind François-Léon Benouville, he was awarded the scholarship because the music category prize went unclaimed. This granted him a five-year residency at the French Academy in Rome's Villa Medici from 1846 to 1851, where he immersed himself in Italian Renaissance art, studying masters like Michelangelo and copying works by Titian to refine his idealization of the human figure.[3][10] During his student years, Cabanel began submitting works to the Paris Salon, debuting in 1843 with Agony in the Garden, which garnered initial notice for its technical polish, though without major awards.[11] His Prix de Rome success automatically qualified subsequent submissions, and upon returning from Italy, The Death of Moses (1850), painted during his Roman sojourn, earned a second-class medal at the 1852 Salon, marking his emerging recognition within the academic establishment.[3][8]Professional Career

Rise to Fame in the 1850s and 1860s

Upon completing his studies abroad, Cabanel returned to France in 1851 and quickly established himself through his participation in the Paris Salon. His painting The Death of Moses, submitted to the 1852 Salon, earned a second-class medal, marking an early professional milestone that highlighted his skill in historical subjects and garnered attention from critics and patrons alike.[3] This success built on his foundational training at the École des Beaux-Arts, positioning him as a rising talent in the academic tradition. Cabanel's reputation solidified further in 1855, when he received a first-class medal at the Salon for his exhibited works and was appointed Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur, recognizing his growing influence during the early years of the Second Empire.[12][13] By the early 1860s, his prominence led to significant commissions from imperial circles, including a portrait of Napoleon III completed around 1865, which was installed in the Empress's study at the Tuileries Palace and praised for its dignified simplicity despite some critical reservations about its modesty.[14] The pinnacle of Cabanel's ascent came in 1863 with the exhibition of The Birth of Venus at the Salon, a sensual yet refined depiction of the mythological figure that captivated audiences and exemplified the era's taste for idealized beauty. The work achieved immediate critical and official acclaim as one of the Salon's major triumphs, earning Cabanel a gold medal and prompting Napoleon III to acquire it directly for his private collection.[15][16] Earlier that year, Cabanel had also exhibited The Florentine Poet at the 1861 Salon, a lyrical portrait that further demonstrated his versatility and popularity among viewers.[4] These achievements during the 1850s and 1860s cemented Cabanel's status as a favored artist of the Second Empire, blending classical mastery with the opulent demands of imperial patronage.Academic Roles and Institutional Influence

Cabanel's success at the 1863 Salon with The Birth of Venus, which earned praise from Napoleon III and widespread acclaim, propelled his institutional ascent. That same year, he was elected to the 10th chair of the Académie des Beaux-Arts within the Institut de France, recognizing his mastery of academic principles and solidifying his status among France's elite artists.[1][17] In 1864, Cabanel was appointed professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, a position he held until his death in 1889, during which he instructed a large number of students and emphasized rigorous classical training.[1][17] This role allowed him to directly shape the curriculum and uphold the school's focus on historical and mythological subjects rendered with precise technique. Cabanel served as a juror for the Paris Salon multiple times, including in 1863—a decision that contributed to the rejection of innovative works like Édouard Manet's Déjeuner sur l'herbe and the subsequent creation of the Salon des Refusés—and on seventeen juries from 1868 to 1888, during which he helped select and award entries that aligned with official tastes.[1][17][2] Throughout the 1860s to 1880s, Cabanel advocated staunchly for academic standards in the face of rising Impressionism, critiquing modernist trends for their departure from disciplined drawing and finish, and using his jury influence to favor works that preserved classical harmony and narrative clarity over experimental techniques.[1][17] His conservative stance reinforced official art policy under the Second Empire and early Third Republic, maintaining the dominance of traditional aesthetics in French institutions.[2]Artistic Style and Techniques

Commitment to Academic Principles

Academic art in 19th-century France, as embodied by the École des Beaux-Arts, was deeply rooted in Renaissance and classical models, drawing from ancient Greek and Roman ideals as well as the works of masters like Raphael and Michelangelo to emphasize technical precision and intellectual rigor.[18] The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, founded in 1648 and evolving into the Académie des Beaux-Arts, established a curriculum centered on drawing from casts, life models, and historical precedents, prioritizing history painting with its demand for narrative clarity and moral elevation over mere decoration.[19] This tradition promoted balanced compositions, harmonious proportions, and idealized human forms to convey timeless truths, often through subjects from mythology, history, or religion that instructed and uplifted the viewer.[18] Alexandre Cabanel exemplified this commitment through his rigorous adherence to these principles, honed during his training under François-Édouard Picot at the École des Beaux-Arts, where he mastered the depiction of idealized anatomy and symmetrical arrangements.[3] His oeuvre consistently featured polished execution, with figures rendered in smooth, enamel-like finishes that prioritized elegance and clarity over raw emotion, ensuring that historical and religious narratives unfolded with compositional poise and thematic restraint.[2] This approach reflected a deliberate focus on classical beauty and moral didacticism, aligning his work with the academy's vision of art as a refined, intellectually grounded pursuit.[3] Cabanel's style marked a rejection of Romantic excess, favoring controlled elegance and ethical themes instead of the dramatic, emotive turbulence championed by artists like Eugène Delacroix.[20] Early experiments with more expressive elements were moderated to conform to academic dictates, underscoring his preference for harmonious restraint that avoided the subjective intensity of Romanticism.[2] As a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts from 1864 and a frequent Salon juror, Cabanel played a pivotal role in upholding these standards against emerging avant-garde movements like Realism and Impressionism, which challenged the academy's emphasis on idealization and tradition. His influence helped maintain the dominance of academic principles in official exhibitions, resisting the radical departures that sought to prioritize personal vision over classical discipline.[19] Through his teaching and jury service, he reinforced the École's legacy, ensuring that academic art remained a bastion of polished, narrative-driven excellence into the late 19th century.[2]Influences and Innovations

Cabanel's artistic development was profoundly shaped by the neoclassical precision of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whose emphasis on clean lines and idealized forms influenced Cabanel's approach to figure drawing and composition, as seen in the poised nudes of works like The Birth of Venus (1863).[1] During his residency at the Villa Medici in Rome from 1846 to 1851, following his 1845 Prix de Rome victory, Cabanel encountered Italian Renaissance masters such as Raphael and Guido Reni, whose harmonious compositions and luminous figures inspired his own grand historical scenes, including Saint John the Baptist (1849).[1] In his studio practice, Cabanel employed meticulous underpainting to establish tonal foundations, followed by glazing layers that achieved the characteristic luminous skin tones in his figures, contributing to the polished, enamel-like finish of paintings such as The Christian Martyr (1855).[1] He relied heavily on live models posed in his studio to ensure anatomical accuracy and vitality, particularly in large-scale compositions like The Death of Moses (1850), where twelve life-size figures were arranged with careful attention to gesture and proportion.[1] Within the constraints of academic tradition, Cabanel innovated by subtly integrating contemporary elegance into classical themes, such as depicting mythological figures with modern hairstyles and attire that evoked Second Empire fashion, lending a familiar allure to ancient subjects in pieces like The Birth of Venus.[21] In response to the rise of photography in the mid-19th century, he incorporated photographic studies as preparatory aids for portraits, allowing precise capture of sitters' features without compromising the idealized purity of his academic style, as evidenced in his portraits of American elites.[22]Major Works

Mythological and Historical Paintings

Alexandre Cabanel's The Birth of Venus (1863), housed in the Musée d'Orsay, stands as one of his most celebrated mythological works, depicting the goddess emerging from the sea on a wave of foam surrounded by playful cupids.[15] This oil on canvas exemplifies Cabanel's mastery of idealized female forms, with Venus portrayed in a languid, sensual pose that symbolizes eternal beauty and harmony, serving as subtle flattery to the opulent aesthetics of Napoleon III's Second Empire.[23] The painting's smooth brushwork and pearlescent skin tones reflect academic principles of graceful modeling and classical perfection.[24] A replica commissioned in 1875 by American collector John Wolfe, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, further popularized the image among international patrons, reinforcing its status as an emblem of refined sensuality.[24] In the 1870s, works like Echo (1874), depicting the nymph pining for Narcissus amid a lush, ethereal landscape, delved into themes of unrequited love and mythological tragedy, with delicate rendering of foliage and figures evoking emotional introspection. These paintings highlight Cabanel's recurring interest in classical narratives, where human emotions are elevated through harmonious composition and luminous color. Cabanel also produced significant historical and religious canvases, such as The Death of Moses (c. 1849–1852), exhibited at the 1852 Salon where it earned a second-prize medal for its poignant depiction of the prophet's final moments, blending solemnity with dynamic grouping to convey moral and narrative depth.[3] Religious themes appear in Jesus in the Praetorium (1845), a dramatic scene of Christ's mockery by Roman soldiers, rendered with intense chiaroscuro and expressive gestures to underscore suffering and divinity, as seen in the Musée d'Orsay's collection.[25] Later historical works like The Death of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta (1870) draw from Dante's Inferno, portraying the tragic lovers in a moment of fatal embrace with scholarly precision and emotional fervor, maintaining fidelity to classical compositional traditions.[26] Cabanel's mythological and historical paintings garnered acclaim at the Salons, particularly The Birth of Venus, which triumphed in 1863 and was immediately acquired by Napoleon III, signaling official endorsement of its polished allure.[15] However, the work sparked controversies over its sensuality, with critics decrying the overt eroticism and objectification of the female nude, contrasting sharply with the rejection of Édouard Manet's more confrontational Olympia that same year.[27] This reception underscored Cabanel's position within academic circles, where his idealized depictions balanced classical reverence with contemporary appeal, influencing perceptions of beauty in mid-19th-century France.[1]Portraits and Commissions

Cabanel's portraiture exemplified his mastery in depicting the French imperial family and European aristocracy with an emphasis on regal poise and dignified elegance. His 1865 Portrait of Napoleon III, commissioned by the emperor for the apartments of Empress Eugénie in the Tuileries Palace, captures the ruler standing in three-quarter view in evening dress with the Légion d'honneur sash, one hand on his hip and the other resting on a table to convey authority and serenity (original lost; replicas exist, e.g., at the Walters Art Museum).[13] This life-size state portrait was Empress Eugénie's favorite depiction of her husband, praised for its faithful rendering of his features and poised demeanor, and it hung prominently in her private study after the fall of the Second Empire.[14] Through such imperial commissions in the 1850s and 1860s, Cabanel solidified his role as the preferred painter of the elite, blending classical composure with subtle psychological insight.[1] Beyond the court, Cabanel received prestigious aristocratic commissions that highlighted his ability to convey social refinement and grace. The 1873 Portrait of the Comtesse de Keller, now in the Hermitage Museum, portrays the sitter in a luxurious black velvet gown with lace details, her direct gaze and elongated posture evoking aristocratic poise against a neutral background that draws attention to her composed features and jewelry.[28] This oil-on-canvas work, measuring 99 x 76 cm, exemplifies Cabanel's smooth modeling and restrained palette, techniques that elevated his subjects to timeless nobility.[29] His portraits often commanded high fees, reflecting his status as a leading society painter whose works were sought by nobility across Europe for their flattering yet sophisticated representations.[3] Cabanel's international appeal extended to American sitters from the Gilded Age elite, who traveled to Paris for commissions that projected an air of European aristocracy. Among his notable American portraits were those of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe (1876, Metropolitan Museum of Art), depicted in a flowing white gown with a serene, direct gaze emphasizing her philanthropy and refinement, and Arabella Huntington (1882, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco), shown in an elegant evening dress that highlights graceful lines and subtle elegance.[22] Other examples include Mary Victoria Leiter (1887, now at Kedleston Hall) and Mary Frick Jacobs (1885, Baltimore Museum of Art), where Cabanel employed a light palette and careful attention to fabrics and posture to convey gentility and wealth.[22] Patrons such as members of the Vanderbilt family, who acquired his historical works, further underscore his draw among transatlantic industrialists seeking prestigious imagery.[22] Over his career, Cabanel exhibited around 40 portraits at the Paris Salons, many featuring such elite female subjects in three-quarter length formats that accentuated poise and social standing.[22] In addition to individual portraits, Cabanel undertook large-scale decorative commissions for public buildings, integrating his portrait-like precision into monumental contexts. For the Louvre, he painted the ceiling of the Cabinet des Dessins, featuring The Triumph of Flora (1870s), a dynamic allegorical ensemble with flowing figures that adorns the museum's graphic arts department and demonstrates his skill in grand, harmonious compositions.[30] These state-sponsored works, alongside private aristocratic portraits, contributed to his commercial success, as his atelier produced numerous high-value commissions that captured the essence of 19th-century elite society.[4]Teaching and Pupils

Students at École des Beaux-Arts

Alexandre Cabanel's studio at the École des Beaux-Arts attracted numerous aspiring artists during his tenure as professor from 1864 onward, fostering a rigorous academic environment that emphasized classical techniques.[31] His teaching approach centered on drawing from antique casts to master proportion and form, followed by sessions with live models to develop skills in rendering the human figure with anatomical precision and idealized beauty.[31] Cabanel provided personalized critiques during atelier gatherings, offering tailored guidance that encouraged students to refine their compositions while adhering to academic standards of harmony and finish.[31] Among his notable pupils in the 1860s and 1870s were Henri Regnault and Jules Bastien-Lepage, both of whom entered Cabanel's studio in the early part of the decade. Regnault, who trained under Cabanel before the Franco-Prussian War, achieved the rare success of winning the Prix de Rome in 1866 with his painting Thetis Bringing the Arms Forged by Vulcan to Achilles, a work showcasing mythological drama and technical virtuosity influenced by his mentor's style.[32] Bastien-Lepage, admitted to the École in 1867, spent two years in Cabanel's atelier honing his draftsmanship through exercises in figure drawing and historical subjects, though he later diverged toward naturalism.[33][32][31] Other prominent students included Édouard Debat-Ponsan and Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret in the late 1860s and 1870s, who absorbed Cabanel's methods of composing grand historical scenes with meticulous attention to light and texture. Debat-Ponsan, for instance, produced The Daughter of Jephthah (1876), a biblical narrative featuring a draped female figure whose poised elegance reflects the academic nudes practiced in Cabanel's classes, earning him a travel bursary as an alternative to the Prix de Rome.[32] Dagnan-Bouveret applied similar techniques to works like Conscripts (1889), blending genre elements with the formal rigor of his training.[32] In the 1870s and 1880s, pupils such as Jean-Eugène Buland, Henri Gervex, and Émile Friant continued under Cabanel's guidance, often transitioning from strict academicism to more contemporary styles. Buland received an honorable mention at the Salon in 1879 and a third-class medal in 1884 for pieces like Le Tripot (The Dive) (1883), which retained Cabanel's influence in its detailed figure rendering despite its naturalist subject.[32] Gervex debuted at the Salon at age 21 with academic portraits, while Friant, entering in 1879, placed second in the 1883 Prix de Rome competition and created The Meurthe Boating Party (1887), incorporating live-model precision in group compositions.[32] Overall, several students, including Regnault, secured the Prix de Rome under Cabanel's tutelage, while others garnered Salon medals, underscoring the effectiveness of his pedagogical focus on foundational skills amid the competitive academic system.[32][34]Impact on Successor Artists

Cabanel's influence extended significantly through his extensive teaching career at the École des Beaux-Arts, where he mentored hundreds of pupils who propagated academic methods into subsequent artistic developments.[21] These students carried forward Cabanel's emphasis on classical composition, meticulous drawing, and idealized forms, contributing to the persistence of conservative academic traditions in French art until around 1900.[35] Many of his pupils, such as Jules Bastien-Lepage and Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, adapted these principles into Naturalism, bridging academic rigor with more contemporary realism, while others explored symbolic elements in historical and mythological subjects, influencing the transition toward Symbolism in the late 19th century.[32] This propagation helped maintain academic dominance in the Salons, where works by Cabanel's students regularly featured, reinforcing the style's prestige amid emerging modernist challenges.[21] His international reach amplified through the prestige of the Paris Salon, where Cabanel's repeated successes—such as his 1865 Medal of Honor—drew American expatriates and other foreign artists to his studio and methods.[22] Wealthy Gilded Age Americans, seeking sophisticated portraits to affirm their social status, flocked to Cabanel, whose polished academic style became a model for expatriate painters like John Singer Sargent, who initially emulated his elegance before evolving toward looser techniques.[22] This cross-Atlantic exchange not only popularized French academicism abroad but also inspired successors, including Cabanel's pupil Théobald Chartran, to sustain the tradition in international portraiture during the Belle Époque.[22] Despite his prominence, Cabanel faced critiques during his lifetime for embodying academic conservatism, often derided as antithetical to innovative movements like Impressionism and Realism, which he actively opposed as a juror and teacher.[2] Posthumously, his style declined with the rise of modernism in the early 20th century, as avant-garde artists rejected academic idealism in favor of abstraction and experimentation.[36] However, a revival of interest in academic figure painting in recent decades has rediscovered Cabanel's contributions, highlighting his technical mastery and role in the Belle Époque's refined aesthetics amid renewed appreciation for 19th-century traditions.[20]Personal Life and Legacy

Family and Later Years

In 1872, Cabanel settled into a hôtel particulier near the Parc Monceau in Paris, where he lived with his brother Barthélémy and nephew Pierre, maintaining his studio within the residence for daily work routines.[37] He made annual summer returns to his hometown of Montpellier, fostering close ties with his family origins.[37] Cabanel's nephew Pierre, who had been his pupil, played a significant role in preserving the family's artistic legacy by donating several of Cabanel's works and drawings to the Musée Fabre in Montpellier, contributing to the institution's substantial holdings of over 50 paintings and 200 drawings by the artist.[38][21] The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 severely disrupted Cabanel's routines in Paris, forcing interruptions to ongoing projects amid the surrounding turmoil, though he resumed his activities in the subsequent years.[21] By the 1880s, Cabanel experienced a marked decline in health owing to chronic asthma and bronchitis, as alluded to in a letter from his sister to him in early 1885, yet he persisted with his studio practice until his final months.[21] As part of his philanthropic efforts, Cabanel donated his 1880 painting Phèdre to the Musée Fabre in Montpellier, enhancing the museum's collection of academic art from his native region.[21]Death and Posthumous Recognition

Alexandre Cabanel died on 23 January 1889 in Paris at the age of 65, following a severe asthma attack the previous day.[3] Despite his failing health, he had continued working until shortly before his death, signing sketches from his studio even as his condition worsened.[3] His passing marked the end of a prolific career, and his funeral was held on 26 January 1889 at the Church of Saint-Philippe-du-Roule in Paris, drawing prominent artists, officials, and admirers in recognition of his status as a leading academic painter.[39] His body was subsequently transported to Montpellier for burial in the Cimetière Saint-Lazare on 28 January.[40] In the immediate aftermath, Cabanel's estate saw significant posthumous activity. A major sale of his studio contents took place from 22 to 25 May 1889 at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris, featuring over 200 works including unfinished paintings, drawings, and studies, which attracted collectors and helped distribute his oeuvre.[21] Several pieces from this period and later acquisitions entered major national collections, underscoring his enduring institutional value; for instance, his monumental Paradise Lost (1867) was purchased for the Musée d'Orsay in 2017 through private sale, joining other key works like The Birth of Venus (1863) already housed there.[41] Public honors followed soon after. In 1892, a funerary monument was erected in Montpellier's Cimetière Saint-Lazare, designed by architect Jean Camille Formigé and featuring a bronze medallion portrait and symbolic elements honoring Cabanel's artistic legacy.[42] This tribute, approved by municipal and ministerial authorities in 1889, reflected local pride in their native son.[42] Cabanel's integration into the Musée d'Orsay's permanent collection further solidified his place in French cultural heritage, with multiple paintings displayed as exemplars of 19th-century academicism.[43] Cabanel's reputation, which had waned in the early 20th century amid the rise of modernism, experienced a notable revival from the late 20th century onward. Scholarly interest in academic art surged, highlighted by the comprehensive retrospective Alexandre Cabanel: La Tradition du Beau organized by the Musée Fabre in Montpellier (2010–2011) and the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne (2011), the first major exhibition since his death that reassessed his technical mastery and cultural role.[1] This renewed attention included feminist critiques examining the sensuality in works like The Birth of Venus, interpreting its passive, idealized female form as reinforcing objectification and patriarchal ideals of beauty, contrasting with more empowered depictions in other artistic traditions.[44] Market interest also resurged post-2000, with auction prices climbing; a preparatory version of The Birth of Venus fetched a record $834,500 at Christie's New York in 2002, signaling growing collector demand for his polished, narrative-driven paintings.[45] More recently, as of 2024–2025, The Birth of Venus was exhibited at the Fundación Mapfre in Madrid.[15]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Men_of_the_Time%2C_eleventh_edition/Cabanel%2C_Alexandre

.jpg/250px-Self_Portrait_(Alexandre_Cabanel).jpg)

.jpg)