Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

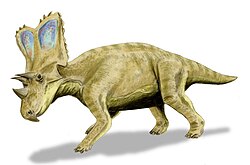

Chasmosaurus

View on Wikipedia

| Chasmosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous (Campanian),

| |

|---|---|

| |

| C. belli skeleton, Royal Ontario Museum specimen 843 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ceratopsia |

| Family: | †Ceratopsidae |

| Subfamily: | †Chasmosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Chasmosaurus Lambe, 1914 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Chasmosaurus (/ˌkæzmoʊˈsɔːrəs/ KAZ-moh-SOR-əs) is a genus of ceratopsid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Period in North America. Its given name means 'opening lizard', referring to the large openings (fenestrae) in its frill (Greek chasma, meaning 'opening', 'hollow', or 'gulf'; and sauros, meaning 'lizard'). With a length of 4.3–4.8 metres (14.1–15.7 ft) and a weight of 1.5–2 tonnes (1.7–2.2 short tons)—or anywhere from 2,200 to nearly 5,000 lbs—Chasmosaurus was of a slightly smaller to "average" size, especially when compared to larger ceratopsids (such as Triceratops, which were about the size of an African bush elephant).

It was initially to be called Protorosaurus, but this name had been previously published for another animal. All of the excavated specimens of Chasmosaurus were collected at the Dinosaur Park Formation, Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada. Referred specimens of C. russelli come from the lower beds of the formation, while C. belli comes from the middle and upper beds.[1]

Discovery and species

[edit]

In 1898, at Berry Creek, Alberta, Lawrence Morris Lambe of the Geological Survey of Canada made the first discovery of Chasmosaurus remains; holotype NMC 491, a parietal bone that was part of a neck frill.[2] Although recognizing that his find represented a new species, Lambe thought this could be placed in a previously known short-frilled ceratopsian genus: Monoclonius.[2] He erected the new species Monoclonius belli to describe his findings.[2] The specific name honoured collector Walter Bell.[3]

However, in 1913, Charles Hazelius Sternberg and his sons found several complete "M. belli" skulls in the middle Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada.[4] Based on these finds, Lambe (1914) erected Protorosaurus ("before Torosaurus"),[5] but that name was preoccupied by the Permian reptile Protorosaurus, so he subsequently created the replacement name Chasmosaurus in February 1914. The name Chasmosaurus is derived from Greek χάσμα, khasma, "opening" or "divide" and refers to the very large parietal fenestrae in the skull frill. Lambe now also assigned a paratype, specimen NMC 2245 found by the Sternbergs in 1913 and consisting of a largely complete skeleton, including skin impressions.[6]

Since that date, more remains, including skulls, have been found that have been referred to Chasmosaurus, and several additional species have been named within the genus.[2] Today some of these are considered to only reflect a morphological variation among the known sample of Chasmosaurus belli skulls;[2] others are seen as valid species of Chasmosaurus or as separate genera. In 1933 Barnum Brown named Chasmosaurus kaiseni, honouring Peter Kaisen and based on skull AMNH 5401, differing from C. belli in having very long brow horns.[7] This form is perhaps related to Chasmosaurus canadensis ('from Canada') named by Thomas M. Lehman in 1990.[8] The latter species, originally Monoclonius canadensis Lambe 1902, had been described as Eoceratops canadensis by Lambe in 1915. Eoceratops and the long-horned Chasmosaurus kaiseni were thought to probably be exemplars of Mojoceratops by Nicholas Longrich,[9] although different teams of researchers have found Mojoceratops to be a synonym of Chasmosaurus russelli. Campbell and colleagues, in their 2016 analysis of Chasmosaurus specimens found Eoceratops and C. kaiseni to be referable to Chasmosaurus sp. due to the lack of the parietal preserved in the holotypes of both.[10] Richard Swann Lull in 1933 named an unusual, short-muzzled skull, specimen ROM 839 (earlier ROM 5436) collected in 1926, as Chasmosaurus brevirostris, "with a short snout".[11] This has been seen as a junior synonym of C. belli.[8]

Charles Mortram Sternberg added Chasmosaurus russelli in 1940, based on specimen NMC 8800 from southwestern Alberta (lower Dinosaur Park Formation). The specific name honours Loris Shano Russell.[4][12] In 1987, Gregory S. Paul renamed Pentaceratops sternbergii into Chasmosaurus sternbergi,[13] but this has found no acceptance. In 2000, George Olshevsky renamed Monoclonius recurvicornis Cope 1889 into Chasmosaurus recurvicornis as its fossil material is likely chasmosaurine;[14] this is a nomen dubium. Thomas Lehman described Chasmosaurus mariscalensis in 1989 from Texas,[15] which has now been renamed Agujaceratops.[16]

The most recently described species is Chasmosaurus irvinensis named in 2001,[17] which stems from the uppermost beds of the Dinosaur Park Formation. This species was given its own genus, Vagaceratops, in 2010.[18] However, Campbell et al. (2019) referred Vagaceratops back to Chasmosaurus.[19] As Fowler and Fowler found Vagaceratops likely to be the sister taxon of Kosmoceratops in 2020, they suggested it should be maintained as a distinct genus from Chasmosaurus, as its placement would probably remain unstable until chasmosaurines are better understood.[20]

The species Mojoceratops perifania was based on holotype specimen TMP 1983.25.1 consisting of a partial skull including the parietal and from the paratypes TMP 1999.55.292, an isolated lateral ramus of a right parietal, and NMC 8803, central bar and lateral rami of parietals. Specimens AMNH 5656, NMC 34832 and TMP 1979.11.147, and (tentatively) AMNH 5401 and NMC 1254 were also referred to the genus. All specimens assigned to Mojoceratops were collected from the Dinosaur Park Formation (late Campanian, 76.5–75 ma) of the Belly River Group of Alberta and Saskatchewan, western Canada. Mojoceratops was named by Nicholas R. Longrich in 2010 and the type species is Mojoceratops perifania. The generic name is derived from mojo and the specific name means "conspicuous pride" in Greek, both referring to the skull frill. The species is based on fossils thought by other researchers to belong to Chasmosaurus.[9]

The species Chasmosaurus kaiseni, known from specimen AMNH 5401, a nearly complete (but partially restored) skull on display at the American Museum of Natural History, was considered to share features in common with Mojoceratops perifania and therefore was considered a possible synonym. However, the parietal (back margin of the frill) is not preserved, and was restored with plaster based on specimens of Chasmosaurus, which caused confusion among scientists in previous decades, because the parietal bone is critical for determining differences between species in ceratopsids like Chasmosaurus and Mojoceratops. Chasmosaurus kaiseni was then by Longrich regarded as a nomen dubium, rather than as the senior synonym of M. perifania. Longrich also regarded the holotype of Eoceratops as probably being an exemplar of Mojoceratops. He considered it too poorly preserved for a reliable determination, especially as it belonged to a juvenile individual, and regarded it too as a nomen dubium, rather than as the senior synonym of M. perifania.[9] A 2016 overview of Chasmosaurus found C. kaiseni and Eoceratops to be referable to Chasmosaurus sp. due to the lack of the parietal preserved in the holotypes of both.[10]

Following the original assignment of the holotype and other skulls to Mojoceratops, several teams of researchers published work questioning the validity of this new genus. In 2011, Maidment & Barrett failed to confirm the presence of any supposedly unique features, and argued that Mojoceratops perifania was a synonym of Chasmosaurus russelli. Campbell and colleagues, in their 2016 analysis of Chasmosaurus specimens, agreed with the conclusions of Maidment & Barrett, adding that some supposedly unique features, such as grooves on the parietal bone, were actually also present in the holotype of C. russelli and, to various degrees, in other Chasmosaurus specimens. This variability, they argued, strongly suggested that Mojoceratops was simply a mature growth stage of C. russelli.[10] Recently, the referral of Eoceratops, C. kaiseni, and Mojoceratops to C. russelli was considered doubtful as the holotype of C. russelli is actually from the upper Dinosaur Park Formation, according to recent fieldwork.[20][10] This situation is further complicated since C. russelli may not even belong to the genus Chasmosaurus, sharing features with the contemporaneous derived chasmosaurine Utahceratops.[21]

Today, taxonomy of Chasmosaurus is in a state of flux. For the aforementioned reasons, it is likely that Mojoceratops, Eoceratops, and C. kaiseni belong to a distinct species, if not genus, of chasmosaurine.[20] Specimens referred to C. russelli are all from the lower Dinosaur Park Formation, stratigraphically and morphologically separate from C. belli.[20] Apart from the holotype and paratype several additional specimens of C. belli are known. These include AMNH 5422, ROM 843 (earlier ROM 5499) and NHMUK R4948, all (partial) skeletons with skull. The skull YPM 2016 and the skull and skeleton AMNH 5402 were noted by Campbell et al. (2016) as differing from other C. belli referred specimens in having more epiparietals, although the authors interpreted them as individual variation, but this was reconsidered when Campbell et al. (2019) interpreted these specimens as an indeterminate Chasmosaurus species closely related to Vagaceratops.[19] The specimen CMN 2245 was referred to the Vagaceratops-like Chasmosaurus species by Fowler and Freedman Fowler (2020), who noted that "given the similarity between these two specimens (YPM 2016 and AMNH 5402) and CMN 2245, it is not clear why CMN 2245 was left in C. belli."[20]

In 2015, Nicholas Longrich presented a novel theory that posits C. belli and C. russelli are synonymous, while splitting some remains assigned to the latter to a new species, C. priscus.[22] Because the publication was rejected, C. "priscus" remains a nomen nudum; however, the name appeared in the pre-proof of the description of Sierraceratops before being edited out for final publication.

Description

[edit]

Chasmosaurus was a medium-size ceratopsid. In 2010 G.S. Paul estimated the length of C. belli at 4.8 metres, its weight at two tonnes; C. russelli would have been 4.3 metres long and weighed 1.5 tonnes.[23]

The known differences between the two species mainly pertain to the horn and frill shape, as the referred postcrania of C. russelli are poorly known. Like many ceratopsians, Chasmosaurus had three main facial horns - one on the nose and two on the brow. In both species these horns are quite short, but with C. russelli they are somewhat longer, especially the brow horns, and more curved backwards. The frill of Chasmosaurus is very elongated and broader at the rear than at the front. It is hardly elevated from the plane of the snout. With C. belli the rear of the frill is V-shaped and its sides are straight. With C. russelli the rear edge is shaped as a shallow U, and the sides are more convex.[23] The sides were adorned by six to nine smaller skin ossifications (called episquamosals) or osteoderms, which attached to the squamosal bone. The corner of the frill featured two larger osteoderms on the parietal bone. With C. russelli the outer one was the largest, with C. belli the inner one. The remainder of the rear edge lacked osteoderms. The parietal bones of the frill were pierced by very large openings, after which the genus was named: the parietal fenestrae. These were not oval in shape, as with most relatives, but triangular, with one point orientated towards the frill corner.

The postcranium of C. belli is best preserved in the specimen known as NHMUK 4948. The first three cervical vertebrae are fused into a unit known as a syncervical, as in other neoceratopsians. There are five other cervicals preserved in this specimen, for a total of eight, which likely represents a complete neck. Cervicals four to eight are amphiplatian, wider than long, and roughly equal in length. The dorsal vertebrae are also amphiplatian. C. belli possessed a synsacrum, a compound unit composed of sacral, dorsal, and sometimes caudal vertebrae, depending on the specimen.[24]

The Chasmosaurus specimen NMC 2245 recovered by C.M. Sternberg was accompanied by skin impressions.[2] The area conserved, from the right hip region, measured about one by 0.5 metres. The skin appears to have had large scales in evenly spaced horizontal rows among smaller scales.[2] The larger scales had a diameter of up to fifty-five millimetres and were distanced from each other by five to ten centimetres. They were hexagonal or pentagonal, thus with five or six sides. Each of these sides touched somewhat smaller scales, forming a rosette. Small, non-overlapping convex scales of about one centimetre in diameter surrounded the whole. The larger scales were wrinkled due to straight grooves orientated perpendicular to their edges. From top to bottom, the large scale rows gradually declined in size.[25] Unfortunately, nothing can as yet be learned about the coloration of Chasmosaurus from the known fossil skin impression samples.

Classification

[edit]

Chasmosaurus was in 1915 by Lambe within the Ceratopsia assigned to the Chasmosaurinae.[26] The Chasmosaurinae usually have long frills, like Chasmosaurus itself, whereas their sister-group the Centrosaurinae typically have shorter frills. Most cladistic analyses show that Chasmosaurus has a basal position in the Chasmosaurinae.S

The following cladogram shows the phylogeny of Chasmosaurus according to a study by Scott Sampson e.a. in 2010.[18]

Paleobiology

[edit]

Chasmosaurus shared its habitat, the east coast of Laramidia, with successive species of Centrosaurus. A certain niche partitioning is suggested by the fact that Chasmosaurus had a longer snout and jaws and might have been more selective about the plants it ate.

The function of the frill and horns is problematic. The horns are rather short and the frill had such large fenestrae that it could not have offered much functional defense. Paul suggested that the beak was the main defensive weapon.[23] It is possible that the frill was simply used to appear imposing or conceivably for thermoregulation. The frill may also have been brightly colored, to draw attention to its size or as part of a mating display. However, it is difficult to prove any sexual dimorphism. In 1933, Lull suggested that C. kaiseni, which bore long brow horns, was in fact the male of C. belli of which the females would have short ones.[11] In 1927 C.M. Sternberg concluded that of the two skeletons he had mounted in the Canadian Museum of Nature, the smaller one, NMC 2245, was the male and the larger, NMC 2280, the female.[27] However, today the two are referred to different species.

A juvenile Chasmosaurus belli found in Alberta, Canada by Phil Currie et al., reveals that Chasmosaurus may have cared for its young, like its relative, Triceratops, is hypothesized to have done. The juvenile measured five feet long and was estimated to be three years of age and had similar limb proportions to the adult Chasmosaurus. This indicates that Chasmosaurus was not fast moving, and that juveniles did not need to be fast moving either to keep pace with adults. The fossil was complete save for its missing front limbs, which had fallen into a sinkhole before the specimen was uncovered. Skin impressions were also uncovered beneath the skeleton and evidence from the matrix that it was buried in indicated that the juvenile ceratopsian drowned during a possible river crossing.[28] Further study of the specimen revealed that juvenile chasmosaurs had a frill that was narrower in the back than that of adults, as well as being proportionately shorter in relation to the skull.[29]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ryan, M.J. & Evans, D.C. (2005). "Ornithischian dinosaurs". In Currie, P.J. & Koppelhus, E.B. (eds.). Dinosaur Provincial Park: A Spectacular Ecosystem Revealed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 312–348.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dodson, Peter; et al. (1993). "Chasmosaurus". The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International. pp. 110–111. ISBN 0-7853-0443-6.

- ^ Lambe, L.M., 1902, "New genera and species from the Belly River Series (mid-Cretaceous)", Geological Survey of Canada Contributions to Canadian Palaeontology 3(2): 25–81

- ^ a b Arbour, V.M.; Burns, M. E.; Sissons, R. L. (2009). "A redescription of the ankylosaurid dinosaur Dyoplosaurus acutosquameus Parks, 1924 (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) and a revision of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1117–1135. Bibcode:2009JVPal..29.1117A. doi:10.1671/039.029.0405. S2CID 85665879.

- ^ Lambe, L.M., 1914, "On the forelimb of a carnivorous dinosaur from the Belly River Formation of Alberta, and a new genus of Ceratopsia from the same horizon, with remarks on the integument of some Cretaceous herbivorous dinosaurs", The Ottawa Naturalist 27(10): 129–135

- ^ Lambe, L.M., 1914, "On Gryposaurus notabilis, a new genus and species of trachodont dinosaur from the Belly River Formation of Alberta, with a description of the skull of Chasmosaurus belli", The Ottawa Naturalist 27: 145–155

- ^ Brown, B., 1933, "A new longhorned Belly River ceratopsian", American Museum Novitates 669: 1–3

- ^ a b T.M. Lehman, 1990, "The ceratopsian subfamily Chasmosaurinae: sexual dimorphism and systematics", In: K. Carpenter and P. J. Currie (eds.), Dinosaur Systematics: Perspectives and Approaches, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 211–229

- ^ a b c Nicholas R. Longrich (2010). "Mojoceratops perifania, A New Chasmosaurine Ceratopsid from the Late Campanian of Western Canada". Journal of Paleontology. 84 (4): 681–694. Bibcode:2010JPal...84..681L. doi:10.1666/09-114.1. S2CID 129168541.

- ^ a b c d Campbell, J.A., Ryan, M.J., Holmes, R.B., and Schröder-Adams, C.J. (2016). A Re-Evaluation of the chasmosaurine ceratopsid genus Chasmosaurus (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Dinosaur Park Formation of Western Canada. PLoS ONE, 11(1): e0145805. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0145805

- ^ a b Lull, R.S., 1933, A revision of the Ceratopsia or horned dinosaurs. Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Natural History 3(3): 1–175

- ^ Sternberg, C.M., 1940, "Ceratopsidae from Alberta", Journal of Paleontology 14(5): 468–480

- ^ Paul, G.S., 1987, "The science and art of reconstructing the life appearance of dinosaurs and their relatives: a rigorous how-to guide", pp 4–49 in: Dinosaurs Past and Present Volume II, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

- ^ Olshevsky, G. 2000. An Annotated Checklist of Dinosaur Species by Continent. George Olshevsky, Publications Requiring Research, San Diego, 157 pp

- ^ Lehman, T.M., 1989, "Chasmosaurus mariscalensis, sp. nov., a new ceratopsian dinosaur from Texas", Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 9(2): 137–162

- ^ Lucas SG, Sullivan RM, Hunt AP (2006). "Re-evaluation of Pentaceratops and Chasmosaurus (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae) in the Upper Cretaceous of the Western Interior". New Mex Mus. Nat. Hist. Sci. Bull. 35: 367–370.

- ^ R.B. Holmes, C.A. Forster, M.J. Ryan and K.M. Shepherd, 2001, "A new species of Chasmosaurus (Dinosauria: Ceratopsia) from the Dinosaur Park Formation of southern Alberta", Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 38: 1423–1438

- ^ a b Scott D. Sampson; Mark A. Loewen; Andrew A. Farke; Eric M. Roberts; Catherine A. Forster; Joshua A. Smith; Alan L. Titus (2010). "New Horned Dinosaurs from Utah Provide Evidence for Intracontinental Dinosaur Endemism". PLOS ONE. 5 (9) e12292. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512292S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012292. PMC 2929175. PMID 20877459.

- ^ a b Campbell, James Alexander; Ryan, Michael J.; Schroder-Adams, Claudia J.; Holmes, Robert B.; Evans, David C. (2019-08-08). "Temporal range extension and evolution of the chasmosaurine ceratopsid 'Vagaceratops' irvinensis (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) in the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta". Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology. 7: 83–100. doi:10.18435/vamp29356. ISSN 2292-1389.

- ^ a b c d e Fowler, Denver W.; Fowler, Elizabeth A. Freedman (2020-06-05). "Transitional evolutionary forms in chasmosaurine ceratopsid dinosaurs: evidence from the Campanian of New Mexico". PeerJ. 8 e9251. doi:10.7717/peerj.9251. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 7278894. PMID 32547873.

- ^ Fowler, Denver Warwick (2017-11-22). "Revised geochronology, correlation, and dinosaur stratigraphic ranges of the Santonian-Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) formations of the Western Interior of North America". PLOS ONE. 12 (11) e0188426. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1288426F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188426. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5699823. PMID 29166406.

- ^ Longrich, Nicholas (2015). "Systematics of Chasmosaurus - new information from the Peabody Museum skull, and the use of phylogenetic analysis for dinosaur alpha taxonomy". F1000Research. 4: 1468. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7573.1.

- ^ a b c Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 269–270

- ^ Maidment, S.C.R.; Barrett, P.M. (2011). "A new specimen of Chasmosaurus belli (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae), a revision of the genus, and the utility of postcrania in the taxonomy and systematics of ceratopsid dinosaurs". Zootaxa. 2963: 1–47. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2963.1.1.

- ^ Sternberg, C.M., 1925, "Integument of Chasmosaurus belli", Canadian Field-Naturalist 39: 108–110

- ^ L.M. Lambe, 1915, "On Eoceratops canadensis, gen. nov., with remarks on other genera of Cretaceous horned dinosaurs", Canada Geological Survey Museum Bulletin 12, Geological Series 24: 1–49

- ^ Sternberg, C.M., 1927, "Horned dinosaur group in the National Museum of Canada", Canadian Field-Naturalist 41: 67–73

- ^ "Rare baby dinosaur skeleton unearthed in Canada". NBC News. 25 November 2013. Retrieved 2019-08-22.

- ^ "Charting the growth of one of the world's oldest babies: Late Cretaceous Chasmosaurus fills in missing pieces of dinosaur evolution". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2019-08-22.