Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for pecking, grasping, and holding (in probing for food, eating, manipulating and carrying objects, killing prey, or fighting), preening, courtship, and feeding young. The terms beak and rostrum are also used to refer to a similar mouth part in some ornithischians, pterosaurs, cetaceans, dicynodonts, rhynchosaurs, anuran tadpoles, monotremes (i.e. echidnas and platypuses, which have a bill-like structure), sirens, pufferfish, billfishes, and cephalopods.

Although beaks vary significantly in size, shape, color and texture, they share a similar underlying structure. Two bony projections–the upper and lower mandibles–are covered with a thin keratinized layer of epidermis known as the rhamphotheca. In most species, two holes called nares lead to the respiratory system.

Etymology

[edit]Although the word "beak" was, in the past, generally restricted to the sharpened bills of birds of prey,[1] in modern ornithology, the terms beak and bill are generally considered to be synonymous.[2] The word, which dates from the 13th century, comes from the Middle English bec (via Anglo-French), which itself comes from the Latin beccus.[3]

Anatomy

[edit]

Although beaks vary significantly in size and shape from species to species, their underlying structures have a similar pattern. All beaks are composed of two jaws, generally known as the maxilla (upper) and mandible (lower).[4](p147) The upper, and in some cases the lower, mandibles are strengthened internally by a complex three-dimensional network of bony spicules (or trabeculae) seated in soft connective tissue and surrounded by the hard outer layers of the beak.[5](p149)[6] The avian jaw apparatus is made up of two units: one four-bar linkage mechanism and one five-bar linkage mechanism.[7]

Mandibles

[edit]

The upper mandible is supported by a three-pronged bone called the intermaxillary. The upper prong of this bone is embedded into the forehead, while the two lower prongs attach to the sides of the skull. At the base of the upper mandible a thin sheet of nasal bones is attached to the skull at the nasofrontal hinge, which gives mobility to the upper mandible, allowing it to move upward and downward.[2]

The base of the upper mandible, or the roof when seen from the mouth, is the palate; the palate's structure differs greatly in the ratites. Here, the vomer is large and connects with premaxillae and maxillopalatine bones in a condition termed as a "paleognathous palate". All other extant birds have a narrow forked vomer that does not connect with other bones and is then termed as neognathous. The shape of these bones varies across the bird families.[a]

The lower mandible is supported by a bone known as the inferior maxillary bone—a compound bone composed of two distinct ossified pieces. These ossified plates (or rami), which can be U-shaped or V-shaped,[4](p147) join distally (the exact location of the joint depends on the species) but are separated proximally, attaching on either side of the head to the quadrate bone. The jaw muscles, which allow the bird to close its beak, attach to the proximal end of the lower mandible and to the bird's skull.[5](p148) The muscles that depress the lower mandible are usually weak, except in a few birds such as the starlings and the extinct huia, which have well-developed digastric muscles that aid in foraging by prying or gaping actions.[8] In most birds, these muscles are relatively small as compared to the jaw muscles of similarly sized mammals.[9]

Rhamphotheca

[edit]

The outer surface of the beak consists of a thin sheath of keratin called the rhamphotheca,[2][5](p148) which can be subdivided into the rhinotheca of the upper mandible and the gnathotheca of the lower mandible.[10](p47) The covering arises from the Malpighian layer of the bird's epidermis,[10](p47) growing from plates at the base of each mandible.[11] There is a vascular layer between the rhamphotheca and the deeper layers of the dermis, which is attached directly to the periosteum of the bones of the beak.[12] The rhamphotheca grows continuously in most birds, and in some species, the color varies seasonally.[13] In some alcids, such as the puffins, parts of the rhamphotheca are shed each year after the breeding season, while some pelicans shed a part of the bill called a "bill horn" that develops in the breeding season.[14][15][16]

While most extant birds have a single seamless rhamphotheca, species in a few families, including the albatrosses[10](p47) and the emu, have compound rhamphothecae that consist of several pieces separated and defined by softer keratinous grooves.[17] Studies have shown that this was the primitive ancestral state of the rhamphotheca, and that the modern simple rhamphotheca resulted from the gradual loss of the defining grooves through evolution.[18]

Tomia

[edit]

The tomia (singular tomium) are the cutting edges of the two mandibles.[10](p598) In most birds, they range from being rounded to slightly sharp, but some species have evolved structural modifications that allow them to handle their typical food sources better.[19] Granivorous (seed-eating) birds, for example, have ridges in their tomia, which help the bird to slice through a seed's outer hull.[20] Most falcons have a sharp projection along the upper mandible, with a corresponding notch on the lower mandible. They use this "tooth" to sever their prey's vertebrae fatally or to rip insects apart. Some kites, principally those that prey on insects or lizards, also have one or more of these sharp projections,[21] as do the shrikes.[22] The tomial teeth of falcons are underlain by bone, while the shrike tomial teeth are entirely keratinous.[23] Some fish-eating species, e.g., the mergansers, have sawtooth serrations along their tomia, which help them to keep hold of their slippery, wriggling prey.[10](p48)

Birds in roughly 30 families have tomia lined with tight bunches of very short bristles along their entire length. Most of these species are either insectivores (preferring hard-shelled prey) or snail eaters, and the brush-like projections may help to increase the coefficient of friction between the mandibles, thereby improving the bird's ability to hold hard prey items.[24] Serrations on hummingbird bills, found in 23% of all hummingbird genera, may perform a similar function, allowing the birds to effectively hold insect prey. They may also allow shorter-billed hummingbirds to function as nectar thieves, as they can more effectively hold and cut through long or waxy flower corollas.[25] In some cases, the color of a bird's tomia can help to distinguish between similar species. The snow goose, for example, has a reddish-pink bill with black tomia, while the whole beak of the similar Ross's goose is pinkish-red, without darker tomia.[26]

Culmen

[edit]

The culmen is the dorsal ridge of the upper mandible.[10](p127) Likened by ornithologist E. Coues[4] to the ridge line of a roof, it is the "highest middle lengthwise line of the bill" and runs from the point where the upper mandible emerges from the forehead's feathers to its tip.[4](p152) The bill's length along the culmen is one of the regular measurements made during bird banding (ringing)[27] and is particularly useful in feeding studies.[28] There are several standard measurements which can be made—from the beak's tip to the point where feathering starts on the forehead, from the tip to the anterior edge of the nostrils, from the tip to the base of the skull, or from the tip to the cere (for raptors and owls)[10](p342)—and scientists from various parts of the world generally favor one method over another.[28] In all cases, these are chord measurements (measured in a straight line from point to point, ignoring any curve in the culmen) taken with calipers.[27]

The shape or color of the culmen can also help with the identification of birds in the field. For example, the culmen of the parrot crossbill is strongly decurved, while that of the very similar red crossbill is more moderately curved.[29] The culmen of a juvenile common loon is all dark, while that of the very similarly plumaged juvenile yellow-billed loon is pale towards the tip.[30]

Gonys

[edit]The gonys is the ventral ridge of the lower mandible, created by the junction of the bone's two rami, or lateral plates.[10](p254) The proximal end of that junction—where the two plates separate—is known as the gonydeal angle or gonydeal expansion. In some gull species, the plates expand slightly at that point, creating a noticeable bulge; the size and shape of the gonydeal angle can be useful in identifying between otherwise similar species. Adults of many species of large gulls have a reddish or orangish gonydeal spot near the gonydeal expansion.[31] This spot triggers begging behavior in gull chicks. The chick pecks at the spot on its parent's bill, which in turn stimulates the parent to regurgitate food.[32]

Commissure

[edit]Depending on its use, commissure may refer to the junction of the upper and lower mandibles,[4](p155) or alternately, to the full-length apposition of the closed mandibles, from the corners of the mouth to the tip of the beak.[10](p105)

Gape

[edit]

In bird anatomy, the gape is the interior of the open mouth of a bird, and the gape flange is the region where the two mandibles join together at the base of the beak.[33] The width of the gape can be a factor in the choice of food.[34]

Gapes of juvenile altricial birds are often brightly coloured, sometimes with contrasting spots or other patterns, and these are believed to be an indication of their health, fitness and competitive ability. Based on that, the parents decide how to distribute food among the chicks in the nest.[35] Some species, especially in the families Viduidae and Estrildidae, have bright spots on the gape known as gape tubercles or gape papillae. These nodular spots are conspicuous even in low light.[36] A study examining the nestling gapes of eight passerine species found that the gapes were conspicuous in the ultraviolet spectrum (visible to birds but not to humans).[37] Parents may, however, not rely solely on the gape coloration, and other factors influencing their decision remain unknown.[38]

Red gape color has been shown in several experiments to induce feeding. An experiment in manipulating brood size and immune system with barn swallow nestlings showed the vividness of the gape was positively correlated with T-cell–mediated immunocompetence, and that larger brood size and injection with an antigen led to a less vivid gape.[39] Conversely, the red gape of the common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) did not induce extra feeding in host parents.[40] Some brood parasites, such as the Hodgson's hawk-cuckoo (C. fugax), have colored patches on the wing that mimic the gape color of the parasitized species.[41]

When born, the chick's gape flanges are fleshy. As it grows into a fledgling, the gape flanges remain somewhat swollen and can thus be used to recognize that a particular bird is young.[42] By the time it reaches adulthood, the gape flanges will no longer be visible.

Nares

[edit]

Most species of birds have external nares (nostrils) located somewhere on their beak. The nares are two holes—circular, oval or slit-like in shape—which lead to the nasal cavities within the bird's skull, and thus to the rest of the respiratory system.[10](p375) In most bird species, the nares are located in the basal third of the upper mandible. Kiwis are a notable exception; their nares are located at the tip of their bills.[19] A handful of species have no external nares. Cormorants and darters have primitive external nares as nestlings, but these close soon after the birds fledge; adults of these species (and gannets and boobies of all ages, which also lack external nostrils) breathe through their mouths.[10](p47) There is typically a septum made of bone or cartilage that separates the two nares, but in some families (including gulls, cranes, and New World vultures), the septum is missing.[10](p47) While the nares are uncovered in most species, they are covered with feathers in a few groups of birds, including grouse and ptarmigans, crows, and some woodpeckers.[10](p375) The feathers over a ptarmigan's nostrils help to warm the air it inhales,[44] while those over a woodpecker's nares help to keep wood particles from clogging its nasal passages.[45]

Species in the bird order Procellariformes have nostrils enclosed in double tubes which sit atop or along the sides of the upper mandible.[10](p375) These species, which include the albatrosses, petrels, diving petrels, storm petrels, fulmars and shearwaters, are widely known as "tubenoses".[46] A number of species, including the falcons, have a small bony tubercule which projects from their nares. The function of the tubercule is unknown. Some scientists suggest it acts as a baffle, slowing down or diffusing airflow into the nares (thus allowing the bird to continue breathing without damaging its respiratory system) during high-speed dives, but this theory has not been proved experimentally. Not all species which fly at high speeds have these tubercules, while some species which fly at low speeds have them.[43]

Operculum

[edit]

The nares of some birds are covered by an operculum (plural opercula), a membraneous, horny or cartilaginous flap.[5](p117)[47] In diving birds, the operculum keeps water out of the nasal cavity;[5](p117) when the birds dive, the impact force of the water closes the operculum.[48] Some species which feed on flowers have opercula to help to keep pollen from clogging their nasal passages,[5](p117) while the opercula of the two species of Attagis seedsnipe help to keep dust out.[49] The nares of nestling tawny frogmouths are covered with large dome-shaped opercula, which help to reduce the rapid evaporation of water vapor, and may also help to increase condensation within the nostrils themselves—both critical functions, since the nestlings get fluids only from the food their parents bring them. The opercula shrink as the birds age, disappearing completely by the time they reach adulthood.[50] In pigeons, the operculum has evolved into a soft swollen mass that sits at the base of the bill, above the nares;[10](p84) though it is sometimes referred to as the cere, this is a different structure.[4](p151) Tapaculos are the only birds known to have the ability to move their opercula.[10](p375)

Rosette

[edit]Some species like the puffin, have a fleshy rosette, sometimes called a "gape rosette"[51] at the corners of the beak. In the puffin, it is grown as part of its display plumage.[52]

Cere

[edit]Birds from a handful of families—including raptors, owls, skuas, parrots, pigeons, turkeys and curassows—have a waxy structure called a cere (from the Latin cera, which means "wax") or ceroma[53][54] which covers the base of their bill. This structure typically contains the nares, except in the owls, where the nares are distal to the cere. Although it is sometimes feathered in parrots,[55] the cere is typically bare and often brightly colored.[19] In raptors, the cere is a sexual signal which indicates the "quality" of a bird; the orangeness of a Montagu's harrier's cere, for example, correlates to its body mass and physical condition.[56] The cere color of young Eurasian scops-owls has an ultraviolet (UV) component, with a UV peak that correlates to the bird's mass. A chick with a lower body mass has a UV peak at a higher wavelength than a chick with a higher body mass does. Studies have shown that parent owls preferentially feed chicks with ceres that show higher wavelength UV peaks, that is, lighter-weight chicks.[57]

The color or appearance of the cere can be used to distinguish between males and females in some species. For example, the male great curassow has a yellow cere, which the female (and young males) lack.[58] The male budgerigar's cere is royal blue, while the female's is a very pale blue, white, or brown.[59]

Nail

[edit]

All birds of the family Anatidae (ducks, geese, and swans) have a nail, a plate of hard horny tissue at the tip of the beak.[60] The shield-shaped structure, which sometimes spans the entire width of the beak, is often bent at the tip to form a hook.[61] It serves different purposes depending on the bird's primary food source. Most species use their nails to dig seeds out of mud or vegetation,[62] while diving ducks use theirs to pry molluscs from rocks.[63] There is evidence that the nail may help a bird to grasp objects. Species which use strong grasping motions to secure their food (such as when catching and holding onto a large squirming frog) have very wide nails.[64] Certain types of mechanoreceptors, nerve cells that are sensitive to pressure, vibration, or touch, are located under the nail.[65]

The shape or color of the nail can sometimes be used to help distinguish between similar-looking species or between various ages of waterfowl. For example, the greater scaup has a wider black nail than does the very similar lesser scaup.[66] Juvenile "grey geese" have dark nails, while most adults have pale nails.[67] The nail gave the wildfowl family one of its former names: "Unguirostres" comes from the Latin ungus, meaning "nail" and rostrum, meaning "beak".[61]

Rictal bristles

[edit]Rictal bristles are stiff hair-like feathers that arise around the base of the beak.[68] They are common among insectivorous birds, but are also found in some non-insectivorous species.[69] Their function is uncertain, although several possibilities have been proposed.[68] They may function as a "net", helping in the capture of flying prey, although to date, there has been no empirical evidence to support this idea.[70] There is some experimental evidence to suggest that they may prevent particles from striking the eyes if, for example, a prey item is missed or broken apart on contact.[69] They may also help to protect the eyes from particles encountered in flight, or from casual contact from vegetation.[70] There is also evidence that the rictal bristles of some species may function tactilely, in a manner similar to that of mammalian whiskers (vibrissae). Studies have shown that Herbst corpuscles, mechanoreceptors sensitive to pressure and vibration, are found in association with rictal bristles. They may help with prey detection, with navigation in darkened nest cavities, with the gathering of information during flight or with prey handling.[70]

Egg tooth

[edit]

Full-term chicks of most bird species have a small sharp, calcified projection on their beak, which they use to chip their way out of their egg.[10](p178) Commonly known as an egg tooth, this white spike is generally near the tip of the upper mandible, though some species have one near the tip of their lower mandible instead, and a few species have one on each mandible.[71] Despite its name, the projection is not an actual tooth, as the similarly-named projections of some reptiles are; instead, it is part of the integumentary system, as are claws and scales.[72] The hatching chick first uses its egg tooth to break the membrane around an air chamber at the wide end of the egg. Then it pecks at the eggshell while turning slowly within the egg, eventually (over a period of hours or days) creating a series of small circular fractures in the shell.[5](p427) Once it has breached the egg's surface, the chick continues to chip at it until it has made a large hole. The weakened egg eventually shatters under the pressure of the bird's movements.[5](p428)

The egg tooth is so critical to a successful escape from the egg that chicks of most species will perish unhatched if they fail to develop one.[71] However, there are a few species which do not have egg teeth. Megapode chicks have an egg tooth while still in the egg but lose it before hatching,[5](p427) while kiwi chicks never develop one; chicks of both families escape their eggs by kicking their way out.[73] Most chicks lose their egg teeth within a few days of hatching,[10](p178) although petrels keep theirs for nearly three weeks[5](p428) and marbled murrelets have theirs for up to a month.[74] Generally, the egg tooth drops off, though in songbirds it is resorbed.[5](p428)

Color

[edit]The color of a bird's beak results from concentrations of pigments—primarily melanins and carotenoids—in the epidermal layers, including the rhamphotheca.[75] Eumelanin, which is found in the bare parts of many bird species, is responsible for all shades of gray and black; the denser the deposits of pigment found in the epidermis, the darker the resulting color. Phaeomelanin produces "earth tones" ranging from gold and rufous to various shades of brown.[76]: 62 Although it is thought to occur in combination with eumelanin in beaks which are buff, tan, or horn-colored, researchers have yet to isolate phaeomelanin from any beak structure.[76]: 63 More than a dozen types of carotenoids are responsible for the coloration of most red, orange, and yellow beaks.[76]: 64

The hue of the color is determined by the precise mix of red and yellow pigments, while the saturation is determined by the density of the deposited pigments. For example, bright red is created by dense deposits of mostly red pigments, while dull yellow is created by diffuse deposits of mostly yellow pigments. Bright orange is created by dense deposits of both red and yellow pigments, in roughly equal concentrations.[76]: 66 Beak coloration helps to make displays using those beaks more obvious.[77](p155) In general, beak color depends on a combination of the bird's hormonal state and diet. Colors are typically brightest as the breeding season approaches, and palest after breeding.[31]

Birds are capable of seeing colors in the ultraviolet range, and some species are known to have ultraviolet peaks of reflectance (indicating the presence of ultraviolet color) on their beaks.[78] The presence and intensity of these peaks may indicate a bird's fitness,[56] sexual maturity or pair bond status.[78] King and emperor penguins, for example, show spots of ultraviolet reflectance only as adults. These spots are brighter on paired birds than on courting birds. The position of such spots on the beak may be important in allowing birds to identify conspecifics. For instance, the very similarly-plumaged king and emperor penguins have UV-reflective spots in different positions on their beaks.[78]

Dimorphism

[edit]

The size and shape of the beak can vary across species as well as between them; in some species, the size and proportions of the beak vary between males and females. That allows the sexes to utilize different ecological niches, thereby reducing intraspecific competition.[79] For example, females of nearly all shorebirds have longer bills than males of the same species,[80] and female American avocets have beaks which are slightly more upturned than those of males.[81] Males of the larger gull species have bigger, stouter beaks than those of females of the same species, and immatures can have smaller, more slender beaks than those of adults.[82] Many hornbills show sexual dimorphism in the size and shape of both beaks and casques, and the female huia's slim, decurved bill was nearly twice as long as the male's straight, thicker one.[10](p48)

Color can also differ between sexes or ages within a species. Typically, such a color difference is due to the presence of androgens. For example, in house sparrows, melanins are produced only in the presence of testosterone; castrated male house sparrows—like female house sparrows—have brown beaks. Castration also prevents the normal seasonal color change in the beaks of male black-headed gulls and indigo buntings.[83]

Development

[edit]The beak of modern birds has a fused premaxillary bone, which is modulated by the expression of Fgf8 gene in the frontonasal ectodermal zone during embryonic development.[84]

The shape of the beak is determined by two modules: the prenasal cartilage during early embryonic stage and the premaxillary bone during later stages. Development of the prenasal cartilage is regulated by genes Bmp4 and CaM, while that of the premaxillary bone is controlled by TGFβllr, β-catenin, and Dickkopf-3.[85][86] TGFβllr codes for a serine/threonine protein kinase that regulates gene transcription upon ligand binding; previous work has highlighted its role in mammalian craniofacial skeletal development.[87] β-catenin is involved in the differentiation of terminal bone cells. Dickkopf-3 codes for a secreted protein also known to be expressed in mammalian craniofacial development. The combination of these signals determines beak growth along the length, depth, and width axes. Reduced expression of TGFβllr significantly decreased the depth and length of chicken embryonic beak due to the underdevelopment of the premaxillary bone.[88] Contrarily, an increase in Bmp4 signaling would result in a reduced premaxillary bone due to the overdevelopment of the prenasal cartilage, which takes up more mesenchymal cells for cartilage, instead of bone, formation.[85][86]

Functions

[edit]

Eating

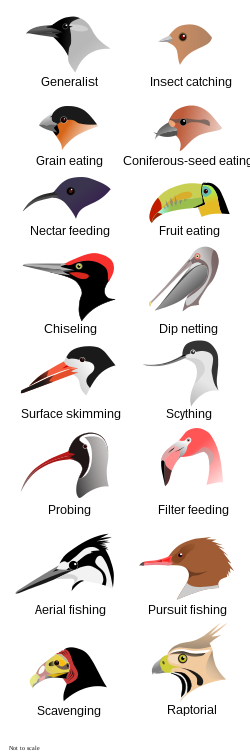

[edit]Different species' beaks have evolved according to their diet; for example, raptors have sharp-pointed beaks that facilitate dissection and biting off of prey animals' tissue, whereas passerine birds that specialize in eating seeds with especially tough shells (such as grosbeaks and cardinals) have large, stout beaks with high compressive power. Diving or fishing birds have beaks adapted for those pursuits; for example, kingfishers have long, pointed beaks adapted for diving into water, while pelicans' beaks are adapted for scooping up and swallowing fish whole. Woodpeckers have thick, pointed beaks adapted for pecking apart wood while hunting for arthropods and insect larvae.

Self-defensive pecking

[edit]Birds may bite or stab with their beaks to defend themselves.[89]

Displays (for courtship, territoriality, or deterrence)

[edit]Some species use their beaks in displays of various sorts. As part of his courtship, for example, the male garganey touches his beak to the blue speculum feathers on his wings in a fake preening display, and the male mandarin duck does the same with his orange sail feathers.[77](p20) A number of species use a gaping, open beak in their fear and/or threat displays. Some augment the display by hissing or breathing heavily, while others clap their beaks. Red-bellied woodpeckers at bird feeders are known to wave their beaks at competing birds who get too close.

Sensory detection

[edit]The platypus uses its bill to navigate underwater, detect food, and dig. The bill contains electroreceptors and mechanoreceptors, causing muscular contractions to help detect prey. It is one of the few species of mammals to use electroreception.[90][91] The beaks of Kiwis, Ibises, and sandpipers have sensory pits in their beaks that allow them to sense vibrations.[92]

The beaks of aquatic birds contain Grandry corpuscles, which assist in velocity detection while filter feeding.

Preening

[edit]The beak of birds plays a role in removing skin parasites (ectoparasites) such as lice. It is mainly the tip of the beak that does this. Studies have shown that inserting a bit to stop birds from using the tip results in increased parasite loads in pigeons.[93] Birds that have naturally deformed beaks have also been noted to have higher levels of parasites.[94][95][96][97] It is thought that the overhang at the end of the top portion of the beak (that is the portion that begins to curve downwards) slides against the lower beak to crush parasites.[93]

This overhang of the beak is thought to be under stabilising natural selection. Very long beaks are thought to be selected against because they are prone to a higher number of breaks, as has been demonstrated in rock pigeons.[98] Beaks with no overhang would be unable to effectively remove and kill ectoparasites as mentioned above. Studies have supported there is a selection pressure for an intermediate amount of overhang. Western scrub jays who had more symmetrical bills (i.e. those with less of an overhang), were found to have higher amounts of lice when tested.[99] The same pattern has been found in surveys of Peruvian birds.[100]

Additionally because of the role beaks play in preening, this is evidence for coevolution of the beak overhang morphology and body morphology of parasites. Artificially removing the ability to preen in birds, followed by readdition of preening ability was shown to result in changes in body size in lice. Once the ability of the birds to preen was reintroduced, the lice were found to show declines in body size suggesting they may evolve in response to preening pressures from birds[93] who could respond in turn with changes in beak morphology.[93]

Communicative percussion

[edit]A number of species, including storks, some owls, frogmouths and the noisy miner, use bill clapping as a form of communication.[77](p83) Some woodpecker species are known to use percussion as a courtship activity, whereas males get the (aural) attention of females from a distance and then impress them with the sound volume and pattern. This explains why humans are sometimes inconvenienced by pecking that clearly has no feeding purpose (such as when the bird pecks on chimneys or sheet metal).

Heat exchange

[edit]Studies have shown that some birds use their beaks to rid themselves of excess heat. The toco toucan, which has the largest beak relative to the size of its body of any bird species, is capable of modifying the blood flow to its beak. This process allows the beak to work as a "transient thermal radiator", reportedly rivaling an elephant's ears in its ability to radiate body heat.[101]

Measurements of the bill sizes of several species of American sparrows found in salt marshes along the North American coastlines show a strong correlation with summer temperatures recorded in the locations where the sparrows breed; latitude alone showed a much weaker correlation. By dumping excess heat through their bills, the sparrows are able to avoid the water loss which would be required by evaporative cooling—an important benefit in a windy habitat where freshwater is scarce.[102] Several ratites, including the common ostrich, the emu and the southern cassowary, use various bare parts of their bodies (including their beaks) to dissipate as much as 40% of their metabolic heat production.[103] Alternately, studies have shown that birds from colder climates (higher altitudes or latitudes and lower environmental temperatures) have smaller beaks, lessening heat loss from that structure.[104]

Billing

[edit]

During courtship, mated pairs of many bird species touch or clasp each other's bills. Termed billing (also nebbing in British English),[105] this behavior appears to strengthen pair bonding.[106] The amount of contact involved varies among species. Some gently touch only a part of their partner's beak while others clash their beaks vigorously together.[107]

Gannets raise their bills high and repeatedly clatter them, the male puffin nibbles at the female's beak, the male waxwing puts his bill in the female's mouth and ravens hold each other's beaks in a prolonged "kiss".[108] Billing can also be used as a gesture of appeasement or subordination. Subordinate Canada jay routinely bill more dominant birds, lowering their body and quivering their wings in the manner of a young bird begging for food as they do so.[109] A number of parasites, including rhinonyssids and Trichomonas gallinae are known to be transferred between birds during episodes of billing.[110][111]

Use of the term extends beyond avian behavior; "billing and cooing" in reference to human courtship (particularly kissing) has been in use since Shakespeare's time,[112] and derives from the courtship of doves.[113]

Beak trimming

[edit]Because the beak is a sensitive organ with many sensory receptors, beak trimming (sometimes referred to as 'debeaking') is "acutely painful"[114] to the birds it is performed on. It is nonetheless routinely done to intensively farmed poultry flocks, particularly laying and broiler breeder flocks, because it helps reduce the damage the flocks inflict on themselves due to a number of stress-induced behaviors, including cannibalism, vent pecking and feather pecking. A cauterizing blade or infrared beam is used to cut off about half of the upper beak and about a third of the lower beak. Pain and sensitivity can persist for weeks or months after the procedure, and neuromas can form along the cut edges. Food intake typically decreases for some period after the beak is trimmed. However, studies show that trimmed poultry's adrenal glands weigh less, and their plasma corticosterone levels are lower than those found in untrimmed poultry, indicating that they are less stressed overall.[114]

A similar but separate practice, usually performed by an avian veterinarian or an experienced birdkeeper, involves clipping, filing or sanding the beaks of captive birds for health purposes–in order to correct or temporarily alleviate overgrowths or deformities and better allow the bird to go about its normal feeding and preening activities.[115]

Among raptor keepers, the practice is commonly known as "coping".[116]

Bill tip organ

[edit]

The bill tip organ is a region found near the tip of the bill in several types of birds that forage particularly by probing. The region has a high density of nerve endings known as the corpuscles of Herbst. This consists of pits in the bill surface which in the living bird is occupied by cells that sense pressure changes. The assumption is that this allows the bird to perform 'remote touch', which means that it can detect movements of animals which the bird does not directly touch. Bird species known to have a 'bill-tip organ' include ibises, shorebirds of the family Scolopacidae, and kiwi.[117]

There is a suggestion that across these species, the bill tip organ is better-developed among species foraging in wet habitats (water column, or soft mud) than in species using a more terrestrial foraging. However, it has been described in terrestrial birds too, including parrots, who are known for their dextrous extractive foraging techniques. Unlike probing foragers, the tactile pits in parrots are embedded in the hard keratin (or rhamphotheca) of the bill, rather than the bone, and along the inner edges of the curved bill, rather than being on the outside of the bill.[118]

See also

[edit]- Bird anatomy – Anatomy of birds

- Rostrum (anatomy) – Anatomy term

- Snout – Extended part of an animal's mouth

- Proboscis – Elongated mouth part

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ For an explanation of desmognathous, aegithognathous, etc. with images see "Catalogue of Species". 1891 – via Archive.org..

References

[edit]- ^ Partington, Charles Frederick (1835). The British cyclopæedia of natural history: Combining a scientific classification of animals, plants, and minerals. Orr & Smith. p. 417.

- ^ a b c Proctor, Noble S.; Lynch, Patrick J. (1998). Manual of Ornithology: Avian structure and function. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-300-07619-6.

- ^ "Beak". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f

Coues, Elliott (1890). Handbook of Field and General Ornithology. London, UK: Macmillan and Co. pp. 1, 147, 151–152, 155. OCLC 263166207. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k

Gill, Frank B. (1995). Ornithology (2nd ed.). New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 149, 427–428. ISBN 978-0-7167-2415-5. - ^ Seki, Yasuaki; Bodde, Sara G.; Meyers, Marc A. (2009). "Toucan and hornbill beaks: A comparative study" (PDF). Acta Biomaterialia. 6 (2): 331–343. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2009.08.026. PMID 19699818. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-02.

- ^ Olsen, A.M. (3–7 Jan 2012). Beyond the beak: Modeling avian cranial kinesis and the evolution of bird skull shapes. Society for Integrative & Comparative Biology. Charleston, South Carolina. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ Mayr, Gerald (2005). "A new eocene Chascacocolius-like mousebird (Aves: Coliiformes) with a remarkable gaping adaptation" (PDF). Organisms, Diversity & Evolution. 5 (3): 167–171. Bibcode:2005ODivE...5..167M. doi:10.1016/j.ode.2004.10.013.

- ^ Kaiser, Gary W. (2007). The Inner Bird: Anatomy and Evolution. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-7748-1343-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s

Campbell, Bruce; Lack, Elizabeth, eds. (1985). A Dictionary of Birds. Carlton, England: T and A.D. Poyser. ISBN 978-0-85661-039-4. - ^ Girling (2003), p. 4.

- ^ Samour (2000), p. 296.

- ^ Bonser, R.H. & Witter, M.S. (1993). "Indentation hardness of the bill keratin of the European starling" (PDF). The Condor. 95 (3): 736–738. doi:10.2307/1369622. JSTOR 1369622.

- ^ Beddard, Frank E. (1898). The structure and classification of birds. London, UK: Longmans, Green and Co. p. 5.

- ^ Pitocchelli, Jay; John F. Piatt; Harry R. Carter (2003). "Variation in plumage, molt, and morphology of the Whiskered Auklet (Aethia pygmaea) in Alaska". Journal of Field Ornithology. 74 (1): 90–98. Bibcode:2003JFOrn..74...90P. doi:10.1648/0273-8570-74.1.90. S2CID 85982302.

- ^ Knopf, F.L. (1974). "Schedule of presupplemental molt of white pelicans with notes on the bill horn" (PDF). Condor. 77 (3): 356–359. doi:10.2307/1366249. JSTOR 1366249.

- ^ Chernova, O.F.; Fadeeva, E.O. (2009). "The peculiar architectonics of contour feathers of the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae, Struthioniformes)". Doklady Biological Sciences. 425: 175–179. doi:10.1134/S0012496609020264. S2CID 38791844.

- ^ Hieronymus, Tobin L.; Witmer, Lawrence M. (2010). "Homology and evolution of avian compound rhamphothecae". The Auk. 127 (3): 590–604. doi:10.1525/auk.2010.09122. S2CID 18430834.

- ^ a b c Stettenheim, Peter R. (2000). "The Integumentary Morphology of Modern Birds—An Overview". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 40 (4): 461–477. doi:10.1093/icb/40.4.461.

- ^ Klasing, Kirk C. (1999). "Avian gastrointestinal anatomy and physiology". Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine. 8 (2): 42–50. doi:10.1016/S1055-937X(99)80036-X.

- ^ Ferguson-Lees, James; Christie, David A. (2001-01-01). Raptors of the World. London, UK: Christopher Helm. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7136-8026-3.

- ^ Harris, Tony; Franklin, Kim (2000). Shrikes and Bush-Shrikes. London, UK: Christopher Helm. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7136-3861-5.

- ^ V. L. Bels; Ian Q. Whishaw, eds. (2019). Feeding in vertebrates: evolution, morphology, behavior, biomechanics. Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-030-13739-7. OCLC 1099968357.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gosner, Kenneth L. (June 1993). "Scopate tomia: An adaptation for handling hard-shelled prey?" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 105 (2): 316–324.

- ^ Ornelas, Juan Francisco. "Serrate Tomia: An Adaptation for Nectar Robbing in Hummingbirds?" (PDF). The Auk. 111 (3): 703–710.

- ^ Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1988). Wildfowl. London, UK: Christopher Helm. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0-7470-2201-5.

- ^ a b c Pyle, Peter; Howell, Steve N. G.; Yunick, Robert P.; DeSante, David F. (1987). Identification Guide to North America Passerines. Bolinas, CA: Slate Creek Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-9618940-0-9.

- ^ a b Borras, A.; Pascual, J.; Senar, J. C. (Autumn 2000). "What Do Different Bill Measures Measure and What Is the Best Method to Use in Granivorous Birds?" (PDF). Journal of Field Ornithology. 71 (4): 606–611. doi:10.1648/0273-8570-71.4.606. JSTOR 4514529. S2CID 86597085.

- ^ Mullarney, Svensson, Zetterström & Grant (1999) p. 357

- ^ Mullarney, Svensson, Zetterström & Grant (1999) p. 15

- ^ a b Howell (2007), p. 23.

- ^ Russell, Peter J.; Wolfe, Stephen L.; Hertz, Paul E.; Starr, Cecie (2008). Biology: The Dynamic Science. Vol. 2. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks / Cole. p. 1255. ISBN 978-0-495-01033-3.

- ^ Newman, Kenneth B. (2000). Newman's birds by colour. Struik. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-86872-448-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Wheelwright, N.T. (1985). "Fruit size, gape width and the diets of fruit-eating birds" (PDF). Ecology. 66 (3): 808–818. Bibcode:1985Ecol...66..808W. doi:10.2307/1940542. JSTOR 1940542. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-08. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

- ^ Soler, J.J.; Avilés, J.M. (2010). Halsey, Lewis George (ed.). "Sibling competition and conspicuousness of nestling gapes in altricial birds: A comparative study". PLoS ONE. 5 (5) e10509. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...510509S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010509. PMC 2865545. PMID 20463902.

- ^ Hauber, Mark & Rebecca M. Kilner (2007). "Coevolution, communication, and host-chick mimicry in parasitic finches: who mimics whom?" (PDF). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 61 (4): 497–503. Bibcode:2007BEcoS..61..497H. doi:10.1007/s00265-006-0291-0. S2CID 44030487. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-20.

- ^ Hunt, Sarah; Kilner, Rebecca M.; Langmore, Naomi E.; Bennett, Andrew T.D. (2003). "Conspicuous, ultravioletrich mouth colours in begging chicks". Biology Letters. 270 (Suppl 1): S‑25–S‑28. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0009. PMC 1698012. PMID 12952627.

- ^ Schuetz, Justin G. (October 2005). "Reduced growth but not survival of chicks with altered gape patterns". Animal Behaviour. 70 (4): 839–848. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.01.007. ISSN 0003-3472. S2CID 53170955.

- ^ Nicola, Saino; Roberto, Ambrosini; Roberta, Martinelli; Paola, Ninni; Anders Pape, Møller (2003). "Gape coloration reliably reflects immunocompetence of barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) nestlings" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology. 14 (1): 16–22. doi:10.1093/beheco/14.1.16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Noble, D.G.; Davies, N.B.; Hartley, I.R.; McRae, S.B. (July 1999). "The Red Gape of the Nestling Cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) is not a supernormal stimulus for three common hosts". Behaviour. 136 (9): 759–777. doi:10.1163/156853999501559. JSTOR 4535638.

- ^ Tanaka, Keita D.; Morimoto, Gen; Ueda, Keisuke (2005). "Yellow wing-patch of a nestling Horsfield's hawk cuckoo Cuculus fugax induces miscognition by hosts: Mimicking a gape?". Journal of Avian Biology. 36 (5): 461–64. doi:10.1111/j.2005.0908-8857.03439.x. Archived from the original on 2012-10-21.

- ^ Zickefoose, Julie. "Backyard Mystery Birds". Bird Watcher's Digest. Retrieved 2010-06-25.

- ^ a b Capainolo, Peter; Butler, Carol (2010). How Fast Can a Falcon Dive?. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8135-4790-9.

- ^ Gellhorn, Joyce (2007). White-tailed ptarmigan: Ghosts of the alpine tundra. Boulder, CO: Johnson Books. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-55566-397-1.

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David S.; Wheye, Darryl (1998). The Birder's Handbook: A field guide to the natural history of North American birds. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-671-65989-9.

- ^ Carboneras, Carlos (1992). "Family Diomedeidae (Albatrosses)". In del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.). Handbook of Birds of the World. Vol. 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. p. 199. ISBN 978-84-87334-10-8.

- ^ Whitney, William Dwight; Smith, Benjamin Eli (1911). The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: The Century Company. p. 4123. LCCN 11031934.

- ^ Bock, Walter J. (1989). "Organisms as functional machines: A connectivity explanation". American Zoologist. 29 (3): 1119–1132. doi:10.1093/icb/29.3.1119. JSTOR 3883510.

- ^ Tudge, Colin (2009). The Bird: A natural history of who birds are, where they came from, and how they live. New York, NY: Crown Publishers. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-307-34204-1.

- ^ Kaplan, Gisela T. (2007). Tawny Frogmouth. Collingwood, Victoria: Csiro Publishing. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-643-09239-6.

- ^ Harris, Mike P. (2014). "Aging Atlantic puffins Fratercula arctica in summer and winter" (PDF). Seabird. 27. Centre for Ecology & Hydrology: 22–40. doi:10.61350/sbj.27.21. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 11, 2016.

- ^ "Skomer Island Puffin" (PDF). www.welshwildlife.org (factsheet). May 2011.

- ^ Webster's Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language

- ^ Eleanor Lawrence (2008). Henderson's Dictionary of Biology (14th ed.). Pearson Benjamin Cummings Prentice Hall. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-321-50579-8.

- ^ Jupiter, Tony; Parr, Mike (2010). Parrots: A Guide to Parrots of the World. A&C Black. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4081-3575-4.

- ^ a b Mougeo, François; Arroyo, Beatriz E. (22 June 2006). "Ultraviolet reflectance by the cere of raptors". Biology Letters. 2 (2): 173–176. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0434. PMC 1618910. PMID 17148356.

- ^ Parejo, Deseada; Avilés, Jesús M.; Rodriguez, Juan (23 April 2010). "Visual cues and parental favouritism in a nocturnal bird". Biology Letters. 6 (2): 171–173. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0769. PMC 2865047. PMID 19864276.

- ^ Leopold, Aldo Starker (1972). Wildlife of Mexico: The Game Birds and Mammals. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-520-00724-6.

- ^ Alderton, David (1996). A Birdkeeper's Guide to Budgies. Tetra Press. p. 12.

- ^ King & McLelland (1985) p. 376

- ^ a b Elliot, Daniel Giraud (1898). The Wild Fowl of the United States and British Possessions. New York, NY: F. P. Harper. p. xviii. LCCN 98001121.

- ^ Perrins, Christopher M. (1974). Birds. London, UK: Collins. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-00-212173-6.

- ^ Petrie, Chuck (2006). Why Ducks Do That: 40 distinctive duck behaviors explained and photographed. Minocqua, WI: Willow Creek Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-59543-050-2.

- ^ Goodman, Donald Charles; Fisher, Harvey I. (1962). Functional Anatomy of the Feeding Apparatus in Waterfowl (Aves: Anatidae). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 179. OCLC 646859135.

- ^ King & McLelland (1985) p. 421

- ^ Dunn, Jon L.; Alderfer, Jonathan, eds. (2006). Field Guide to the Birds of North America (5 ed.). Washington, DC: National Geographic. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7922-5314-3.

- ^ Mullarney, Svensson, Zetterström & Grant (1999) p. 40

- ^ a b Lederer, Roger J. "The Role of Avian Rictal Bristles" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 84 (2): 193–197.

- ^ a b Conover, Michael R.; Miller, Don E. (November 1980). "Rictal Bristle Function in Willow Flycatcher" (PDF). The Condor. 82 (4): 469–471. doi:10.2307/1367580. JSTOR 1367580.

- ^ a b c Cunningham, Susan J.; Alley, Maurice R.; Castro, Isabel (January 2011). "Facial Bristle Feather Histology and Morphology in New Zealand Birds: Implications for Function". Journal of Morphology (PDF). 272 (1): 118–128. Bibcode:2011JMorp.272..118C. doi:10.1002/jmor.10908. PMID 21069752. S2CID 20407444.

- ^ a b Perrins, Christopher M.; Attenborough, David; Arlott, Norman (1987). New Generation Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-292-75532-1.

- ^ Clark, George A. Jr. (September 1961). "Occurrence and timing of egg teeth in birds" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 73 (3): 268–278.

- ^ Harris, Tim, ed. (2009). National Geographic Complete Birds of the World. Washington, DC: National Geographic. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4262-0403-6.

- ^ Kaiser, Gary W. (2007). The Inner Bird: Anatomy and evolution. Vancouver, BC: University of Washington Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7748-1344-0.

- ^ Ralph, Charles L. (May 1969). "The Control of Color in Birds". American Zoologist. 9 (2): 521–530. doi:10.1093/icb/9.2.521. JSTOR 3881820. PMID 5362278.

- ^ a b c d

Hill, Geoffrey E. (2010). National Geographic Bird Coloration. Washington, DC: National Geographic. pp. 62–66. ISBN 978-1-4262-0571-2. - ^ a b c Rogers, Lesley J.; Kaplan, Gisela T. (2000). Songs, Roars and Rituals: Communication in birds, mammals and other animals. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 20, 83, 155. ISBN 978-0-674-00827-4.

- ^ a b c Jouventin, Pierre; Nolan, Paul M.; Örnborg, Jonas; Dobson, F. Stephen (February 2005). "Ultraviolet spots in king and emperor penguins". The Condor. 113 (3): 144–150. doi:10.1650/7512. S2CID 85776106.

- ^ Campbell, Bernard Grant, ed. (1972). Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man: The Darwinian pivot. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-202-02005-1.

- ^ Thompson, Bill; Blom, Eirik A.T.; Gordon, Jeffrey A. (2005). Identify Yourself: The 50 most common birding identification challenges. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-618-51469-4.

- ^ O'Brien, Michael; Crossley, Richard; Karlson, Kevin (2006). The Shorebird Guide. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-618-43294-3.

- ^ Howell (2007) p. 21

- ^

Parkes, A.S.; Emmens, C.W. (1944). "Effect of androgens and estrogens on birds". In Harris, Richard S.; Thimann, Kenneth Vivian (eds.). Vitamins and hormones. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Academic Press. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-12-709802-9.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S.; Morris, Zachary S.; Sefton, Elizabeth M.; Tok, Atalay; Tokita, Masayoshi; Namkoong, Bumjin; Camacho, Jasmin; Burnham, David A.; Abzhanov, Arhat (July 2015). "A molecular mechanism for the origin of a key evolutionary innovation, the bird beak and palate, revealed by an integrative approach to major transitions in vertebrate history: DEVELOPMENTAL MECHANISM FOR ORIGIN OF BIRD BEAK". Evolution. 69 (7): 1665–1677. doi:10.1111/evo.12684. PMID 25964090. S2CID 205124061.

- ^ a b Abzhanov, Arhat; Protas, Meredith; Grant, B. Rosemary; Grant, Peter R.; Tabin, Clifford J. (2004-09-03). "Bmp4 and Morphological Variation of Beaks in Darwin's Finches". Science. 305 (5689): 1462–1465. Bibcode:2004Sci...305.1462A. doi:10.1126/science.1098095. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15353802. S2CID 17226774.

- ^ a b Abzhanov, Arhat; Kuo, Winston P.; Hartmann, Christine; Grant, B. Rosemary; Grant, Peter R.; Tabin, Clifford J. (August 2006). "The calmodulin pathway and evolution of elongated beak morphology in Darwin's finches". Nature. 442 (7102): 563–567. Bibcode:2006Natur.442..563A. doi:10.1038/nature04843. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16885984. S2CID 2416057.

- ^ Ito, Yoshihiro; Yeo, Jae Yong; Chytil, Anna; Han, Jun; Bringas, Pablo; Nakajima, Akira; Shuler, Charles F.; Moses, Harold L.; Chai, Yang (2003-11-01). "Conditional inactivation of Tgfbr2 in cranial neural crest causes cleft palate and calvaria defects". Development. 130 (21): 5269–5280. doi:10.1242/dev.00708. ISSN 1477-9129. PMID 12975342. S2CID 10925294.

- ^ Mallarino, R.; Grant, P. R.; Grant, B. R.; Herrel, A.; Kuo, W. P.; Abzhanov, A. (2011-03-08). "Two developmental modules establish 3D beak-shape variation in Darwin's finches". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (10): 4057–4062. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.4057M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011480108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3053969. PMID 21368127.

- ^ Samour (2000) p. 7

- ^ Patel, Meera (Fall 2007). "Platypus electroreception". Biology 342: Animal Behavior. Portland, OR: Reed College.

- ^ "Platypus". LiveScience. 4 August 2014. 27572.

- ^ "Vibration-sensing beak organ found in ibises, kiwi birds, and sandpipers". 2021. doi:10.1036/1097-8542.BR0105211.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ a b c d

Clayton, [deficient citation]; Lee, [deficient citation]; Tompkins, [deficient citation]; Brodie, [deficient citation] (September 1999). "Reciprocal Natural Selection on Host-Parasite Phenotypes" (PDF). The American Naturalist. 154 (3): 261–270. Bibcode:1999ANat..154..261C. doi:10.1086/303237. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30056229. ISSN 1537-5323. PMID 10506542. S2CID 4369897. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-09-12. Retrieved 2019-09-05.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)[full citation needed] - ^ Pomeroy, D.E. (February 1962). "Birds with abnormal bills" (PDF). British Birds. 55 (2): 49–72. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-02-19. Retrieved 2018-02-18.

- ^

Boyd, [deficient citation] (1951). "A survey of parasitism of the Staling Sturnus vulgaris L. in North America". Journal of Parasitology. 37 (1): 56–84. doi:10.2307/3273522. JSTOR 3273522. PMID 14825028.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)[full citation needed] - ^

Worth, [deficient citation] (1940). "A note on the dissemination of Mallophage". Bird-Banding. 11: 23, 24.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)[full citation needed] - ^

Ash, [deficient citation] (1960). "A study of the mallophaga of birds with particular reference to their ecology". Ibis. 102: 93–110. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1960.tb05095.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)[full citation needed] - ^ Clayton, Dale H.; Moyer, Brett R.; Bush, Sarah E.; Jones, Tony G.; Gardiner, David W.; Rhodes, Barry B.; Goller, Franz (2005-04-22). "Adaptive significance of avian beak morphology for ectoparasite control". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 272 (1565): 811–817. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.3036. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1599863. PMID 15888414.

- ^ Moyer, Brett R.; Peterson, A. Townsend; Clayton, Dale H. (2002). "Influence of bill shape on ectoparasite load in western scrub-jays" (PDF). The Condor. 104 (3): 675–678. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2002)104[0675:iobsoe]2.0.co;2. hdl:1808/16618. ISSN 0010-5422. S2CID 32708877.

- ^ Clayton, D.H.; Walther, B.A. (2001-09-01). "Influence of host ecology and morphology on the diversity of Neotropical bird lice". Oikos. 94 (3): 455–467. Bibcode:2001Oikos..94..455C. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2001.940308.x. ISSN 1600-0706.

- ^ Tattersall, Glenn J.; Andrade, Denis V.; Abe, Augusto S. (24 July 2009). "Heat Exchange from the Toucan Bill Reveals a Controllable Vascular Thermal Radiator". Science. 325 (5949): 468–470. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..468T. doi:10.1126/science.1175553. PMID 19628866. S2CID 42756257.

- ^ Greenbert, Russell; Danner, Raymond; Olsen, Brian; Luther, David (14 July 2011). "High summer temperature explains bill size variation in salt marsh sparrows". Ecography. online first (2): 146–152. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2011.07002.x.

- ^ Phillips, Polly K.; Sanborn, Allen F. (December 1994). "An infrared, thermographic study of surface temperature in three ratites: Ostrich, emu and double-wattled cassowary". Journal of Thermal Biology. 19 (6): 423–430. Bibcode:1994JTBio..19..423P. doi:10.1016/0306-4565(94)90042-6.

- ^ "Evolution of bird bills: Birds reduce their 'heating bills' in cold climates". Science Daily. 23 June 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ Bierma, Nathan (12 August 2004). "Add this to life list: 'Birding' has inspired flock of words". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ Terres, John K. (1980). The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-46651-4.

- ^ Schreiber, Elizabeth Anne; Burger, Joanna, eds. (2002). Biology of Marine Birds. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-8493-9882-7.

- ^ Armstrong (1965) p. 7

- ^ Wilson, Edward O. (1980). Sociobiology. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-674-81624-4.

- ^ Amerson, A. Binion (May 1967). "Incidence and Transfer of Rhinonyssidae (Acarina: Mesostigmata) in Sooty Terns (Sterna fuscata)". Journal of Medical Entomology. 4 (2): 197–9. doi:10.1093/jmedent/4.2.197. PMID 6052126.

- ^ Park, F. J. (March 2011). "Avian trichomoniasis: A study of lesions and relative prevalence in a variety of captive and free-living bird species as seen in an Australian avian practice". The Journal of the Australia Veterinary Association. 89 (3): 82–88. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2010.00681.x. PMID 21323655.

- ^ Partridge, Eric (2001). Shakespeare's bawdy (4 ed.). London, UK: Routledge Classics 2001. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-415-25553-0.

- ^ Burton, Maurice; Burton, Robert (1980). The International Wildlife Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York, NY: Marshall Cavendish Corp. p. 1680.

- ^ a b Grandin, Temple (2010). Improving Animal Welfare: A practical approach. Oxfordshire, UK: CABI. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-84593-541-2.

- ^ Race Foster; Marty Smith. "Bird Beaks: Anatomy, care, and diseases". Pet Education. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.[self-published source?]

- ^ Ash, Lydia (2020) [2004]. "Coping your Raptor". The Modern Apprentice. Archived from the original on 2005-04-06. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ Cunningham, Susan J.; Alley, M.R.; Castro, I.; Potter, M.A.; Cunningham, M.; Pyne, M.J. (2010). "Bill morphology or Ibises suggests a remote-tactile sensory system for prey detection". The Auk. 127 (2): 308–316. doi:10.1525/auk.2009.09117. S2CID 85254980.

- ^ Demery, Zoe P.; Chappell, J.; Martin, G.R. (2011). "Vision, touch and object manipulation in Senegal parrots Poicephalus senegalus". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 278 (1725): 3687–3693. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0374. PMC 3203496. PMID 21525059.

Bibliography

[edit]- Armstrong, Edward Allworthy (1965). Bird Display and Behaviour: An introduction to the study of bird psychology. New York, NY: Dover Publications. LCCN 64013457.

- Campbell, Bruce; Lack, Elizabeth, eds. (1985). A Dictionary of Birds. Carlton, England: T and A.D. Poyser. ISBN 978-0-85661-039-4.

- Coues, Elliott (1890). Handbook of Field and General Ornithology. London, UK: Macmillan and Co. p. 1. OCLC 263166207.

- Gilbertson, Lance (1999). Zoology Lab Manual (4 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Companies. ISBN 978-0-07-237716-3.

- Gill, Frank B. (1995). Ornithology (2 ed.). New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0-7167-2415-5.

- Girling, Simon (2003). Veterinary Nursing of Exotic Pets. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-0747-1.

- Hill, Geoffrey E. (2010). National Geographic Bird Coloration. Washington, DC: National Geographic. ISBN 978-1-4262-0571-2.

- Howell, Steve N. G. (2007). Gulls of the Americas. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-618-72641-7.

- King, Anthony Stuart; McLelland, John, eds. (1985). Form and Function in Birds. Vol. 3. London, UK: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-407503-0.

- Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars; Zetterström, Dan; Grant, Peter J. (1999). Collins Bird Guide: The Most Complete Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. London, UK: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-711332-3.

- Proctor, Noble S.; Lynch, Patrick J. (1998). Manual of Ornithology: Avian Structure and Function. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07619-6.

- Rogers, Lesley J.; Kaplan, Gisela T. (2000). Songs, Roars and Rituals: Communication in birds, mammals and other animals. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00827-4.

- Samour, Jaime, ed. (2000). Avian Medicine. London, UK: Mosby. ISBN 978-0-7234-2960-9.

Etymology

Linguistic Origins and Usage

The term "beak" derives from Middle English bec, adopted around the mid-13th century from Old French bec (meaning "beak" or "bird's bill"), which stems from Late Latin beccus, likely of Gaulish or Proto-Celtic origin (bekkos, denoting "beak" or "small beak").[5][6] The earliest recorded use in English appears circa 1220 in a bestiary text, initially describing a bird's bill or projecting tip, often with figurative extensions to noses or prows.[7] In ornithology, "beak" originally emphasized the sharpened, hooked bills of birds of prey, distinguishing it from the broader term "bill," which derives from Old English bile or bill (meaning "bird's beak" or "blade").[8] Over time, particularly by the 19th century, the distinction blurred, with modern scientific literature employing "beak" and "bill" interchangeably to refer to the keratin-covered jaws of birds, reflecting no substantive anatomical difference.[9] This evolution aligns with expanded anatomical studies, where "beak" now encompasses diverse avian forms, from probing shorebird bills to crushing parrot structures, while avoiding restriction to predatory species.[10] Beyond birds, English usage extends "beak" to analogous structures in non-avian taxa, such as the chitinous mouthparts of insects (e.g., hemipteran "beaks" for piercing) or the leathery jaws of cephalopods like squid, rooted in the term's core connotation of a projecting, functional appendage.[6] Colloquial applications, including British slang for a magistrate (from the 16th century, evoking authoritative "pecking" or nasal imagery), persist but remain peripheral to primary zoological meanings.[5]Evolutionary History

Origins in Theropod Dinosaurs

The beak of modern birds originated as a keratinous rhamphotheca covering the rostral portions of the jaws in theropod dinosaurs, representing an evolutionary innovation that paralleled edentulism and enhanced cranial biomechanics. Fossil evidence from derived theropods, including coelurosaurs, demonstrates that toothless beaks evolved convergently at least six times within Theropoda, often associated with dietary shifts toward herbivory or omnivory rather than solely flight-related reductions in weight.[11][12] This development occurred as early as the Late Jurassic, with ontogenetic tooth loss and beak formation documented in the ceratosaurian Limusaurus inextricabilis from the Shishugou Formation in China, dated to approximately 161–155 million years ago.[13] In Limusaurus, juveniles exhibited dentigerous jaws with up to 12 maxillary teeth per side, but adults developed edentulous snouts with a beak-like structure inferred from the deepened, edentulous premaxillae and dentaries, marking the only known instance of postnatal tooth loss and beak acquisition in a reptile.[13] Similar precursors appeared in maniraptoriform theropods, such as the therizinosaur Erlikosaurus andrewsi from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian–Turonian stages, ~95–90 million years ago) of Mongolia, where CT scans reveal edentulous premaxillae and dentary tips consistent with a keratinous rhamphotheca.[12] Oviraptorosaurians, closer to the avian lineage, also possessed robust, toothless rostra with minute mandibular foramina suggesting keratin sheathing, as seen in specimens from Early Cretaceous formations.[14] Biomechanical analyses indicate that these early beaks provided structural advantages, reducing von Mises stress and strain during feeding by distributing loads more evenly across the cranium compared to toothed snouts.[12] Rostral keratin evolution in theropods typically followed partial toothrow reduction, with phylogenetic models showing no direct causation of complete edentulism but facilitation of dietary specialization through lighter, more stable jaws.[15] Developmental conservation, evidenced by a shared "power cascade" growth pattern in rostral bone radius across theropod snouts spanning over 200 million years, underscores how beak shapes arose from modular, scalable mechanisms rather than radical innovations.[11] These theropod origins laid the groundwork for the full avian rhamphotheca, which further diversified post-Cretaceous extinction among neornithine birds.[11]Tooth Loss and Beak Emergence

The loss of teeth in the avian lineage occurred in the common ancestor of all modern birds (Neornithes) approximately 116 million years ago during the Early Cretaceous period, as evidenced by shared inactivating mutations in multiple genes responsible for tooth enamel formation across 48 sequenced bird genomes.[16][17] These mutations, affecting at least six key genes including those for enamel proteins, prevented the development of mineralized tooth caps, rendering the jaws edentulous while preserving underlying odontogenic signaling pathways that could theoretically support tooth formation if reactivated.[18][19] Unlike earlier Mesozoic birds such as Archaeopteryx (circa 150 million years ago), which retained conical teeth suited for grasping prey, and diverse enantiornithine and ornithurine taxa with variable dentition and tooth replacement cycles akin to reptiles, crown-group birds underwent this singular loss without evidence of long-term directional selection toward toothlessness across broader Mesozoic avialan evolution.[20][21][22] Concurrent with tooth loss, the beak emerged as a keratinous rhamphotheca—a horny sheath covering the bony mandibles—providing mechanical advantages for food processing and egg hatching without the metabolic costs of continuous tooth regeneration. Fossil evidence from Early Cretaceous species like Confuciusornis reveals disassociated rhamphotheca fragments, indicating early development of this sheath alongside reducing dentition, which likely facilitated stress distribution during feeding and pipping.[2][23] This transition reduced skull weight, enabling more efficient flight, and supported faster embryonic development by allowing precise eggshell penetration with the beak's tip rather than cumbersome teeth, potentially shortening incubation periods as a selective driver in lineages adapting to diverse ecological niches.[2] Some extinct neornithine groups, such as Odontopterygiformes, secondarily evolved bony pseudoteeth along the beak edges for enhanced prey capture, underscoring the beak's versatility as a post-dental innovation rather than a direct replacement.[24] Overall, these changes reflect opportunistic adaptations to lightweight cranial architecture and reproductive efficiency, rather than a uniform progression from teeth to beak dictated by feeding ecology alone.[25]Adaptive Radiation and Natural Selection

Adaptive radiation in bird beaks refers to the rapid diversification of beak morphologies from a common ancestor, enabling exploitation of varied ecological niches through natural selection. Following the emergence of toothless beaks in early avialans, this process accelerated in isolated environments like islands, where reduced competition allowed beak shapes to specialize for specific food sources such as seeds, insects, nectar, or fish. Natural selection acted on heritable variations in beak size, depth, and curvature, favoring traits that improved foraging efficiency and survival during environmental shifts.[26][27] The Galápagos finches exemplify this phenomenon, descending from a single South American ancestor that arrived approximately 2 million years ago and radiated into at least 15 species with distinct beak forms. Ground finches evolved robust, deep beaks for cracking large seeds, while warbler finches developed slender beaks for insectivory, and vegetarian finches acquired notched beaks for tearing cactus. Long-term field studies by Peter and Rosemary Grant on Daphne Major island documented natural selection in action: during a 1977 drought, medium ground finches with deeper beaks (averaging 0.5 mm deeper) survived better by accessing harder seeds, shifting the population mean beak depth by 4-5% in one generation, with heritability estimates around 0.65-0.85. Subsequent wet periods and parasite outbreaks reversed or reinforced these shifts, demonstrating beak traits' responsiveness to fluctuating selection pressures tied to food availability and competition.[28][29][30] Similarly, Hawaiian honeycreepers underwent adaptive radiation from a single finch-like ancestor around 5-7 million years ago, producing over 50 species with beaks ranging from long, curved nectar-probing tubes to stout seed-crackers and insect-spearing bills. This diversification correlated with volcanic island formation, providing sequential colonization opportunities and niche vacancies, with natural selection optimizing beak geometry for pollen, fruits, or arthropods amid low mammalian predation. Fossil and genetic evidence confirms that ecological specialization, rather than sexual selection alone, drove these beak evolutions, though many species now face extinction from introduced diseases and habitat loss.[31][26] In both cases, genetic underpinnings, such as variants in the ALX1 and BMP4 genes regulating beak depth and width, facilitated rapid evolutionary responses to selection, underscoring how modular beak development enables adaptive radiation without compromising overall cranial integrity. While microevolutionary changes in small clades like these finches are clearly driven by natural selection on ecological traits, broader avian radiations may incorporate additional factors like key innovations or mass extinctions, yet beak adaptability remains a primary axis of diversification across Aves.[32][33]Recent Evolutionary Adaptations

One prominent example of recent evolutionary adaptation in bird beaks is observed in Darwin's finches of the Galápagos Islands, where beak morphology has demonstrably shifted in response to environmental pressures over decades. Long-term field studies on Daphne Major island, spanning from 1973 to the present, document changes in beak size and shape driven by fluctuations in seed availability, particularly during droughts that favor birds with deeper, stronger beaks capable of cracking harder seeds. For instance, following a 1977 drought, medium ground finches (Geospiza fortis) with larger beaks survived at higher rates, leading to a heritable increase in average beak depth by approximately 4-5% within one generation, as measured through parent-offspring correlations and genomic analysis. A 2023 genomic study of these populations revealed that 45% of beak size variation is attributable to just six loci, with allele frequency shifts confirming natural selection's role in rapid adaptation over 30 years, independent of genetic drift.[34][35] These adaptations extend beyond size to functional morphology, influencing feeding efficiency and even mating signals; beak shape variations alter song production, reinforcing species isolation amid ecological divergence. Hybridization events, such as the emergence of a new lineage from a 1981 immigrant male and resident females, further illustrate ongoing speciation tied to beak traits suited to novel niches, with descendants exhibiting distinct beak forms for specialized insectivory. Such microevolutionary changes align with fossil evidence of faster evolutionary rates in avian rostra compared to other skull elements, underscoring beaks' lability in adapting to selective pressures like food scarcity or interspecific competition.[36] In invasive populations, beak evolution can occur rapidly post-colonization. European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) introduced to North America in 1890 exhibit beaks 8% longer than those in their native European range, based on morphometric comparisons of museum specimens collected over 206 years. This elongation, absent in native populations over the same timeframe, correlates with expanded dietary opportunities in urban and agricultural habitats, including access to softer foods like fruits and insects, though climatic factors like warmer winters may contribute via phenotypic plasticity initially fixed by selection. The pattern holds across sexes and age classes, with statistical models ruling out measurement artifacts or translocation effects, highlighting invasion as a catalyst for morphological divergence.[37] Other cases, such as subtle lengthening in British great tits potentially linked to feeder use rather than feeders per se, suggest anthropogenic landscapes can accelerate beak trait shifts, but rigorous longitudinal data confirm selection on existing variation rather than de novo evolution. These examples collectively demonstrate that avian beak adaptations remain dynamic on contemporary timescales, governed by ecological feedbacks and genetic architectures that enable precise responses to shifting resources.[3]Anatomy

Mandibles and Keratin Sheath

The avian beak consists of an upper mandible derived from the premaxillary and maxillary bones and a lower mandible formed by the dentary, angular, and other ossified elements, providing the primary skeletal framework. These bony cores are lightweight yet robust, adapted for mechanical stress during feeding and other activities.[38][39] Overlaying these mandibles is the rhamphotheca, a thin, horny sheath composed mainly of β-keratin proteins, which originates from the stratified squamous epithelium and lacks pigmentation in its basal layers but may incorporate pigments superficially. The rhamphotheca subdivides into the rhinotheca covering the upper mandible and the gnathotheca on the lower mandible, with the two meeting at the commissure or gape.[40][39][41] A vascular dermal layer, rich in blood vessels and nerve endings, lies between the bony core and the rhamphotheca, facilitating nutrient supply, thermoregulation, and sensory feedback; this intermediate zone enables the beak's continuous growth at rates varying by species, typically 0.1 to 0.3 mm per day in many passerines to offset abrasion from use.[42][43][38] The germinative epithelium at the base of the rhamphotheca drives its lifelong renewal, with keratinization occurring as cells migrate rostrally; in some taxa, the sheath features imbricated scales or compound plates that enhance durability or flexibility, as observed in parrots and raptors. Disruptions to this growth, such as nutritional deficiencies, can lead to overgrowth or deformities, underscoring the sheath's dependence on systemic health.[44][45]Cutting Edges and Structural Features

The cutting edges of a bird's beak, known as the tomia (singular: tomium), form the sharp margins along the upper (rhynchotheca) and lower (gnathotheca) mandibles of the rhamphotheca, enabling precise manipulation and processing of food.[46] These edges are composed of densely keratinized epidermal tissue, which provides durability and resistance to wear during foraging.[1] In many species, the tomia align closely to create a scissor-like action for shearing vegetation or flesh, with their structure varying based on dietary needs—smooth and chisel-like in granivores for cracking seeds, or reinforced for harder materials.[47] Serrated tomia, featuring small tooth-like projections, are adaptations for gripping slippery prey such as fish or insects, as seen in mergansers where sawtooth edges prevent escape during capture.[10] Similarly, geese exhibit transverse ridges along the tomia to tear fibrous grasses, functioning analogously to mammalian incisors without true dentition.[48] In hummingbirds, minute serrations on the tomia aid in snaring small arthropods, challenging earlier assumptions of exclusive nectar-feeding and highlighting predatory capabilities.[49] Scopate tomia, characterized by brush-like fringes of fine ridges, occur in shorebirds like oystercatchers and facilitate handling hard-shelled mollusks by wedging into shells or rasping flesh.[50] Hooked tomia, prominent in raptors such as falcons, feature a sharply curved tip on the upper mandible that overlaps the lower, optimized for tearing carrion or live prey with high bite forces concentrated at the edge.[51] This hook, often reinforced by underlying bony projections, enhances mechanical leverage, with the tomium's keratin layer absorbing impacts without fracturing. Structural integrity of the tomia derives from layered keratin deposition, vascular cores for nutrient supply, and conformity to the mandibular bones, allowing self-sharpening through abrasion while minimizing weight.[53] These features underscore causal adaptations driven by selective pressures for efficient energy extraction from diverse ecologies, rather than uniform design.[54]Sensory and Accessory Elements

Bird beaks feature specialized sensory structures, primarily mechanoreceptors, that enable tactile detection crucial for foraging. Herbst corpuscles, lamellated nerve endings unique to birds, are densely distributed in the bill tips of probe-foraging species such as sandpipers, ibises, and kiwis, allowing them to sense vibrations and locate hidden prey through remote touch without visual cues.[55] These corpuscles, embedded in pits within the beak's bony core, evolved during the Cretaceous period over 70 million years ago, as evidenced by fossil records of enantiornithine birds.[56] In seabirds like albatrosses and penguins, similar high-density Herbst corpuscles and nerve concentrations in the beak tip facilitate prey detection in low-visibility aquatic environments.[57] Grandry corpuscles complement Herbst corpuscles in some species, particularly aquatic birds, providing sensitivity to textures, pressure, and transient touch stimuli during food processing.[58] Beaks generally contain numerous nerve endings that detect temperature, pressure, and mechanical stimuli, aiding in manipulation of objects and food.[40] Additionally, iron-rich magnetite structures in the beaks of pigeons and migratory birds function as magnetoreceptors, contributing to orientation and navigation by sensing Earth's magnetic field.[59] Accessory elements include the cere, a soft, waxy skin patch at the base of the upper mandible in raptors, parrots, and pigeons, which encases the nostrils (nares) and supports respiration while potentially indicating sex or health through color and texture variations.[60] Rictal bristles, stiff feather-like structures around the beak's corners in certain passerines and nightjars, associate with Herbst corpuscles to enhance tactile sensing near the mouth.[61] Nares, positioned on the cere or upper mandible, primarily serve olfaction, though most birds rely weakly on smell; exceptions like kiwis possess enlarged olfactory bulbs linked to foraging via scent.[55]Developmental Biology

Embryonic Formation