Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chirk Castle

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

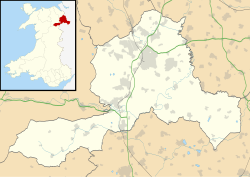

Chirk Castle (Welsh: Castell y Waun) is a Grade I listed castle located in Chirk, Wrexham County Borough, Wales,[1][2] 1.5 mi (2.4 km) from Chirk railway station, now owned and run by the National Trust.

Key Information

History

[edit]The castle was built in 1295 by Roger Mortimer de Chirk, uncle of Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March as part of Edward I's chain of fortresses across the north of Wales, guarding the entrance to the Ceiriog Valley. It was the administrative centre for the Marcher Lordship of Chirkland. It was run as a March castle by the Layards Edwardes of Chirk until removed by the Star Chamber when it was taken up by the Myddelton family. The Edwardes coat of arms is preserved in the castle. Edwardes became the Barony of Kensington.[clarification needed]

The castle was bought by Sir Thomas Myddelton in 1593 for £5,000 (approx. £18 million as of 2024[update]). His son, Thomas Myddelton of Chirk Castle was a Parliamentarian during the English Civil War, but became a Royalist during the 'Cheshire rising' of 1659 led by George Booth, 1st Baron Delamer. Mullioned and transomed windows were inserted in the 16th and 17th centuries; the castle was partly demolished in the English Civil War and then rebuilt.[3] Following the Restoration, his son became Sir Thomas Myddelton, 1st Baronet of Chirke.[4] The castle passed down in the Myddelton family to Charlotte Myddelton (on the death of her father in 1796). Charlotte had married Robert Biddulph, who changed his name to Robert Myddelton-Biddulph, leaving the castle on his death to their son Robert. It then passed down in the Myddelton-Biddulph family.

From before World War I until after World War II the castle was leased by Thomas Scott-Ellis, 8th Baron Howard de Walden, a prominent patron of the arts and champion of Welsh culture. In 1918 Chirk Castle was used as film location for Victory and Peace, directed by Herbert Brenon. The baron opened up parts of the castle to evacuees during the later part of the Second World War.[5][6] The Myddelton family returned to live at Chirk Castle until 2004.[7] Lieutenant-Colonel Ririd Myddleton was an extra equerry to Queen Elizabeth II from 1952 until his death in 1988.

Chirk remained in the Myddelton family until it was transferred to the National Trust in 1981;[8] the castle and gardens are open to the public.[9]

Landscape

[edit]The property is notable for its gardens, with clipped yew hedges, herbaceous borders, rock gardens and terraces, and surrounded by 18th-century parkland.[9]

This parkland was originally laid out as a deer park in the 14th century. From the early 17th century there were both formal and kitchen gardens adjacent to the castle, probably on the eastern side. The gardens continued to develop after the English Civil War, including the construction of an outer courtyard to the north, surrounded by stone walls with a wrought-iron gateway. By 1719 the courtyard had been turfed over and the gates replaced by a magnificent set of wrought-iron gates and gate screen made by Robert and John Davies of Bersham.[10]

A panoramic view of the park by Thomas Badeslade, published in 1742, shows the resulting grand baroque layout of formal gardens and avenues. This included formal gardens to the east of the castle, with a walled outer courtyard and kitchen gardens to the north.[11] Most of this layout was swept away by extensive landscaping in the 1760s and 70s, undertaken by William Emes on behalf of Richard Myddelton, including the construction of a ha-ha and the removal of the Davies gates to be re-erected at the New Hall entrance.[3] These works were largely responsible for the present-day appearance of the park.

A prominent feature of the park is the earthwork of Offa's Dyke, which passes within 200 yards of the castle. This is shown on the Badeslade drawing, labelled as 'King Offa's Ditch', with the ornamental lake beyond.[12] The earthwork was partly submerged by the creation of the lake. In 2018 and 2018 the Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust excavated a section across Offa's Dyke here, and found substantial remains of the ditch and bank.[13] The parkland landscape had partly been responsible for preserving the remains of the Dyke.[14]

The Oak at the Gate of the Dead lies 300 yards from Chirk Castle, and marks the site of the 1165 Battle of Crogen.[15]

The castle was used as a special stage in the 2013 Wales Rally GB.

The parks and gardens are listed as Grade I in the Cadw/ICOMOS Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in Wales.[16]

Gallery

[edit]-

The north east prospect of Chirk Castle, in Denbighshire, 1735

-

A north view of Chirk Castle, c. 1810

-

Chirk Castle Approach

-

The castle gates

-

Main entrance

-

Courtyard

-

Garden alongside the castle

-

Chirk Castle from the North, by Peter Tillemans, 1725

-

The west prospect of Chirk Castle c. 1733–1747

-

Adam Tower from the south-west

-

The courtyard and turret clock from the east

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Chirk Castle, Chirk". British Listed buildings. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Cadw. "Chirk Castle (Grade I) (598)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ a b Register of Landscapes, Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in Wales. Part 1 Parks and Gardens: Clwyd, Cadw/ICOMOS, 1995

- ^ "Chirk Castle – Official Guidebook". Castle Wales.

- ^ "BBC - WW2 People's War - an Evacuee in Chirk".

- ^ "The evacuees who were made kings of our castles". 26 June 2005.

- ^ "A Welshman's home is NOT his castle". 24 March 2004.

- ^ "National Trust collections page: Chirk Castle". Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Chirk Castle". National Trust.

- ^ Gallagher, Christopher (1996), Chirk Castle: a Survey of the Landscape. National Trust, National Trust

- ^ Grant, Ian; Foreman, Penelope; Logan, William, Chirk Castle, Wrexham: Offa's Dyke, Northern Gardens and West building, Community Excavation 2019, Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust

- ^ Grant, Ian; Foreman, Penelope; Logan, William, Chirk Castle, Wrexham: Offa's Dyke, Northern Gardens and West building, Community Excavation 2019, Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust

- ^ Belford, Paul (January 2020), "Enigmatic earthworks: excavating on Offa's and Wat's Dyke", Current Archaeology (358)

- ^ Belford, Paul (2019). "Hidden Earthworks: Excavation and Protection of Offa's and Wat's Dykes". Offa's Dyke Journal. 1 (1): 80. doi:10.23914/odj.v1i0.251.

- ^ "The Oak at the Gate of the Dead". People's Collection Wales. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Cadw. "Chirk Castle (PGW(C)63(WRE))". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

External links

[edit]- Mahler, Margaret (1912), A History of Chirk Castle and Chirkland, London: G. Bell and Sons

- Chirk Castle information at the National Trust

- www.geograph.co.uk : photos of Chirk Castle and surrounding area

- List of paintings on show at Chirk castle