Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Merchant

View on Wikipedia

A merchant is a person who trades in goods produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Merchants have been known for as long as humans have engaged in trade and commerce. Merchants and merchant networks operated in ancient Babylonia, Assyria, China, Egypt, Greece, India, Persia, Phoenicia and Rome. During the European medieval period, a rapid expansion in trade and commerce led to the rise of a wealthy and powerful merchant class. The European Age of Discovery opened up new trading routes and gave European consumers access to a much broader range of goods. By the 18th century, a new type of manufacturer-merchant had started to emerge and modern al) for the purpose of generating profit, cash flow, sales, and revenue using a combination of human, financial, intellectual and physical capital with a view to fueling economic development and growth.

Etymology

[edit]

The English term, merchant comes from the Middle English, marchant, which is derived from Anglo-Norman marchaunt, which itself originated from the Vulgar Latin mercatant or mercatans, formed from present participle of mercatare ('to trade, to traffic or to deal in').[1] The term refers to any type of reseller, but can also be used with a specific qualifier to suggest a person who deals in a given characteristic such as speed merchant, which refer to someone who enjoys fast driving; noise merchant, which refers to a group of musical performers;[2] and dream merchant, which refers to someone who peddles idealistic visionary scenarios.

Types of merchants

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

Broadly, merchants can be classified into two categories:

- A wholesale merchant operates in the chain between the producer and retail merchant, typically dealing in large quantities of goods.[3] In other words, a wholesaler does not sell directly to end-users. Some wholesale merchants only organize the movement of goods rather than move the goods themselves.

- A retail merchant or retailer sells merchandise to end-users or consumers (including businesses), usually in small quantities. A shop-keeper is an example of a retail merchant.

However, the term 'merchant' is often used in a variety of specialised contexts such as in merchant banker, merchant navy or merchant services.

History

[edit]Merchants in antiquity

[edit]

Merchants have existed as long as humankind have conducted business, trade or commerce.[4][5][6][7][8][9] A merchant class operated in many pre-modern societies. Open-air, public markets, where merchants and traders congregated, functioned in ancient Babylonia and Assyria, China, Egypt, Greece, India, Persia, Phoenicia and Rome. These markets typically occupied a place in the town's centre. Surrounding the market, skilled artisans, such as metal-workers and leather workers, occupied premises in alley ways that led to the open market-place. These artisans may have sold wares directly from their premises, but also prepared goods for sale on market days.[10][need quotation to verify] In ancient Greece markets operated within the agora (open space), and in ancient Rome in the forum. Rome's forums included the Forum Romanum, the Forum Boarium and Trajan's Forum. The Forum Boarium, one of a series of fora venalia or food markets, originated, as its name suggests, as a cattle market.[11] Trajan's Forum was a vast expanse, comprising multiple buildings with shops on four levels. The Roman forum was arguably the earliest example of a permanent retail shop-front.[12]

In antiquity, exchange involved direct selling through permanent or semi-permanent retail premises such as stall-holders at market places or shop-keepers selling from their own premises or through door-to-door direct sales via merchants or peddlers.[citation needed] The nature of direct selling centred around transactional exchange, where the goods were on open display, allowing buyers to evaluate quality directly through visual inspection. Relationships between merchant and consumer were minimal[13] often playing into public concerns about the quality of produce.[14]

The Phoenicians became well known amongst contemporaries as "traders in purple" – a reference to their monopoly over the purple dye extracted from the murex shell.[15] The Phoenicians plied their ships across the Mediterranean, becoming a major trading power by the 9th century BCE. Phoenician merchant traders imported and exported wood, textiles, glass and produce such as wine, oil, dried fruit and nuts. Their trading necessitated a network of colonies along the Mediterranean coast, stretching from modern-day Crete through to Tangiers (in present-day Morocco) and northward to Sardinia.[16] The Phoenicians not only traded in tangible goods, but were also instrumental in transporting the trappings of culture. The Phoenicians' extensive trade networks necessitated considerable book-keeping and correspondence. In around 1500 BCE, the Phoenicians developed a script which was much easier to learn than the pictographic systems used in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Phoenician traders and merchants were largely responsible for spreading their alphabet around the region.[17] Phoenician inscriptions have been found in archaeological sites at a number of former Phoenician cities and colonies around the Mediterranean, such as Byblos (in present-day Lebanon) and Carthage in North Africa.[18]

The social status of the merchant class varied across cultures; ranging from high status (the members even eventually achieving titles such as that of Merchant Prince or Nabob) to low status, as in China, Greece and Roman cultures, owing to the presumed distastefulness of profiting from "mere" trade rather than from labor or the labor of others as in agriculture and craftsmanship.[19] The Romans defined merchants or traders in a very narrow sense. Merchants were those who bought and sold goods, while landowners who sold their own produce were not classed as merchants. Being a landowner was a "respectable" occupation. In contrast, the Romans did not consider the activities of merchants "respectable".[20] In the ancient cities of the Middle East, where the bazaar was the city's focal point and heartbeat, merchants who worked in bazaar enjoyed high social status and formed part of local elites.[21] In Medieval Western Europe, the Christian church, which closely associated merchants' activities with the sin of usury, criticised the merchant class, strongly influencing attitudes towards them.[22]

In Greco-Roman society, merchants typically did not have high social status, though they may have enjoyed great wealth.[23] Umbricius Scauras, for example, was a manufacturer and trader of garum in Pompeii, circa 35 C.E. His villa, situated in one of the wealthier districts of Pompeii, was very large and ornately decorated in a show of substantial personal wealth. Mosaic patterns in the floor of his atrium were decorated with images of amphorae bearing his personal brand and inscribed with quality claims. One of the inscriptions on the mosaic amphora reads "G(ari) F(los) SCO[m]/ SCAURI/ EX OFFI[ci]/NA SCAU/RI" which translates as "The flower of garum, made of the mackerel, a product of Scaurus, from the shop of Scaurus". Scaurus' fish sauce had a reputation for very high quality across the Mediterranean; its fame travelled as far away as modern southern France.[24] Other notable Roman merchants included Marcus Julius Alexander (16 – 44 CE), Sergius Orata (fl. c. 95 BCE) and Annius Plocamus (1st century CE).[citation needed]

In the Roman world, local merchants served the needs of the wealthier landowners. While the local peasantry, who were generally poor, relied on open-air market places to buy and sell produce and wares, major producers such as the great estates were sufficiently attractive for merchants to call directly at their farm-gates. The very wealthy landowners managed their own distribution, which may have involved exporting.[25] Markets were also important centres of social life, and merchants helped to spread news and gossip.[26]

The nature of export markets in antiquity is well documented in ancient sources and in archaeological case-studies. Both Greek and Roman merchants engaged in long-distance trade. A Chinese text records that a Roman merchant named Lun reached southern China in 226 CE. Archaeologists have recovered Roman objects dating from the period 27 BCE to 37 CE from excavation sites as far afield as the Kushan and Indus ports. The Romans sold purple and yellow dyes, brass and iron; they acquired incense, balsam, expensive liquid myrrh and spices from the Near East and India, fine silk from China[27] and fine white marble destined for the Roman wholesale market from Arabia.[28] For Roman consumers, the purchase of goods from the East was a symbol of social prestige.[29]

Merchants in the medieval period

[edit]

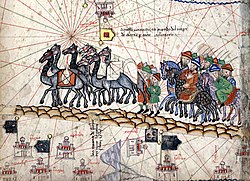

Medieval England and Europe witnessed a rapid expansion in trade and the rise of a wealthy and powerful merchant class. Blintiff has investigated the early medieval networks of market towns and suggests that by the 12th century there was an upsurge in the number of market towns and the emergence of merchant circuits as traders bulked up surpluses from smaller regional, different day markets and resold them at the larger centralised market towns. Peddlers or itinerant merchants filled any gaps in the distribution system.[30] From the 11th century, the Crusades helped to open up new trade routes in the Near East, while the adventurer and merchant, Marco Polo stimulated interest in the far East in the 13th century. Medieval merchants began to trade in exotic goods imported from distant shores including spices, wine, food, furs, fine cloth (notably silk), glass, jewellery and many other luxury goods. Market towns began to spread across the landscape during the medieval period.[citation needed]

Merchant guilds began to form during the medieval period. A fraternity formed by the merchants of Tiel in Gelderland (in present-day Netherlands) in 1020 is believed to be the first example of a merchant guild. The term, guild was first used for gilda mercatoria and referred to body of merchants operating out of St. Omer, France in the 11th century. Similarly, London's Hanse was formed in the 12th century.[31] These guilds controlled the way that trade was to be conducted and codified rules governing the conditions of trade. Rules established by merchant guilds were often incorporated into the charters granted to market towns. In the early 12th century, a confederation of merchant guilds, formed out of the German cities of Lübeck and Hamburg, known as the Hanseatic League came to dominate trade around the Baltic Sea. By the 13th and 14th centuries, merchant guilds had sufficient resources to have erected guild halls in many major market towns.[32]

During the thirteenth century, European businesses became more permanent and were able to maintain sedentary merchants and a system of agents. Merchants specialised in financing, organisation and transport while agents were domiciled overseas and acted on behalf of a principal. These arrangements first appeared on the route from Italy to the Levant, but by the end of the thirteenth century merchant colonies could be found from Paris, London, Bruges, Seville, Barcelona and Montpellier. Over time these partnerships became more commonplace and led to the development of large trading companies. These developments also triggered innovations such as double-entry book-keeping, commercial accountancy, international banking including access to lines of credit, marine insurance and commercial courier services. These developments are sometimes known as the commercial revolution.[33]

Luca Clerici has made a detailed study of Vicenza's food market during the sixteenth century. He found that there were many different types of merchants operating out of the markets. For example, in the dairy trade, cheese and butter was sold by the members of two craft guilds (i.e., cheesemongers who were shopkeepers) and that of the so-called ‘resellers’ (hucksters selling a wide range of foodstuffs), and by other sellers who were not enrolled in any guild. Cheesemongers’ shops were situated at the town hall and were very lucrative. Resellers and direct sellers increased the number of sellers, thus increasing competition, to the benefit of consumers. Direct sellers, who brought produce from the surrounding countryside, sold their wares through the central market place and priced their goods at considerably lower rates than cheesemongers.[34]

From 1300 through to the 1800s a large number of European chartered and merchant companies were established to exploit international trading opportunities. The Company of Merchant Adventurers of London, chartered in 1407, controlled most of the fine cloth imports[35] while the Hanseatic League controlled most of the trade in the Baltic Sea. A detailed study of European trade between the thirteenth and fifteenth century demonstrates that the European age of discovery acted as a major driver of change. In 1600, goods travelled relatively short distances: grain 5–10 miles; cattle 40–70 miles; wool and wollen cloth 20–40 miles. However, in the years following the opening up of Asia and the discovery of the New World, goods were imported from very long distances: calico cloth from India, porcelain, silk and tea from China, spices from India and South-East Asia and tobacco, sugar, rum and coffee from the New World.[36]

In Mesoamerica, a tiered system of traders developed independently. The local markets, where people purchased their daily needs were known as tianguis while pochteca referred to long-distance, professional merchants traders who obtained rare goods and luxury items desired by the nobility. This trading system supported various levels of pochteca – from very high status merchants through to minor traders who acted as a type of peddler to fill in gaps in the distribution system.[37] The Spanish conquerors commented on the impressive nature of the local and regional markets in the 15th century. The Mexica (Aztec) market of Tlatelolco was the largest in all the Americas and said to be superior to those in Europe.[38]

In much of Renaissance Europe and even after, merchant trade remained seen as a lowly profession and it was often subject to legal discrimination or restrictions, although in a few areas its status began to improve.[39][40][41][42][43]

Merchants in the modern era

[edit]The modern era is generally understood to refer to period that started with the rise of consumer culture in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe.[44][need quotation to verify] As standards of living improved in the 17th century, consumers from a broad range of social backgrounds began to purchase goods that were in excess of basic necessities. An emergent middle class or bourgeoisie stimulated demand for luxury goods, and the act of shopping came to be seen as a pleasurable pastime or form of entertainment.[45] 16th century Spanish and 17th century English nobles had been enticed into participating in trade by the profitability of colonial expeditions. In the 17th century, members of the nobility in many European countries like France or Spain still disliked engaging in merchant activities, but such attitudes changed in the 18th century with governmental encouragement of nobles to invest in trade, and the lifting of old bans on nobles engaging in economic activities.[46]

As Britain continued colonial expansion, large commercial organisations came to provide a market for more sophisticated information about trading conditions in foreign lands. Daniel Defoe (c. 1660–1731), a London merchant, published information on trade and economic resources of England, Scotland and India.[47][48] Defoe was a prolific pamphleteer. His many publications include titles devoted to trade, including: Trade of Britain Stated (1707); Trade of Scotland with France (1713); The Trade to India Critically and Calmly Considered (1720) and A Plan of the English Commerce (1731); all pamphlets that became highly popular with contemporary merchants and business houses.[49]

Armenians operated as a prominent trade nation during the 17th century. They stood out in international trade due to their vast network – mostly built by Armenian migrants spread across Eurasia. Armenians had established prominent trade-relations with all big export players such as India, China, Persia, the Ottoman Empire, England, Venice, the Levant, etc. Soon they captured Eastern and Western Europe, Russia, the Levant, the Middle East, Central Asia, India, and the Far East trade routes, carrying out mostly caravan-trade activities. A significant reason for Armenians' massive involvement in international trade was their geographic location – the Armenian lands stand at the crossroads between Asia and Europe. Another reason was their religion, as they were a Christian nation isolated between Muslim Iran and Muslim Turkey. European Christians preferred to carry out trade with Christians in the region.[50]

Eighteenth-century merchants who traded in foreign markets developed a network of relationships which crossed national boundaries, religious affiliations, family ties, and gender. The historian, Vannneste, has argued that a new "cosmopolitan merchant mentality" based on trust, reciprocity and a culture of communal support developed and helped to unify the early modern world. Given that these cosmopolitan merchants were embedded within their societies and participated in the highest level of exchange, they transferred a more outward-looking mindset and system of values to their commercial-exchange transactions, and also helped to disseminate a more global awareness to broader society and therefore acted as agents of change for local society. Successful, open-minded cosmopolitan merchants began to acquire a more esteemed social position within the political elites. They were often sought as advisors for high-level political agents.[51] The English nabobs belong to this era.

By the eighteenth century, a new type of manufacturer-merchant was emerging and modern business practices were becoming evident. Many merchants held showcases of goods in their private homes for the benefit of wealthier clients.[52] Samuel Pepys, for example, writing in 1660, describes being invited to the home of a retailer to view a wooden jack.[53] McKendrick, Brewer and Plumb found extensive evidence of eighteenth-century English entrepreneurs and merchants using "modern" marketing techniques, including product differentiation, sales promotion and loss-leader pricing.[54] English industrialists, Josiah Wedgewood (1730–1795) and Matthew Boulton (1728–1809), are often portrayed as pioneers of modern mass-marketing methods.[55] Wedgewood was known to have used marketing techniques such as direct mail, travelling salesmen and catalogues in the eighteenth century.[56] Wedgewood also carried out serious investigations into the fixed and variable costs of production and recognised that increased production would lead to lower unit-costs. He also inferred that selling at lower prices would lead to higher demand and recognised the value of achieving scale economies in production. By cutting costs and lowering prices, Wedgewood was able to generate higher overall profits.[57] Similarly, one of Wedgewood's contemporaries, Matthew Boulton, pioneered early mass-production techniques and product differentiation at his Soho Manufactory in the 1760s. He also practiced planned obsolescence and understood the importance of "celebrity marketing" – that is supplying the nobility, often at prices below cost – and of obtaining royal patronage, for the sake of the publicity and kudos generated.[58] Both Wedgewood and Boulton staged expansive showcases of their wares in their private residences or in rented halls.[59]

Eighteenth-century American merchants, who had been operating as importers and exporters, began to specialise in either wholesale or retail roles. They tended not to specialise in particular types of merchandise, often trading as general merchants, selling a diverse range of product types. These merchants were concentrated in the larger cities. They often provided high levels of credit financing for retail transactions.[60]

A system of credit was especially important because there was a shortage of cash in Britain and America following the Revolutionary War.[61] Because the state of both countries was so tumultuous after the war, an honor system was essential to establish social bonds. Without a system to keep people accountable, professional relationships are destroyed, innocent people are left to pay the debts of the perpetrators, and entire trade networks are left financially ruined.[62]

Historian Jon Stobart explained in an article that the way merchants often entered these networks was via apprenticeships, and the personal connections made during these relationships “reinforced the status of the merchant[s].”[63] Stobart further elaborates that these bonds between masters and apprentices allowed merchants to be known to other people, and more importantly, to be trusted by others.[64] However, the way this social hierarchy was initially introduced allowed it to become rife with exploitation.

This is explained in many anecdotes like the story of Daniel Parker, a merchant from Watertown, Massachusetts, who was part of a major commercial network. He was able to escape his debts merely by escaping on a ship to Europe. leaving his friends and family to clean up his mess.[65] If too many people were to exploit these loopholes, it would cause the entire system to collapse. Parker was said to "maintain his innocence" despite all the charges of fraud because of his change in environment. In Europe, he had a neutral reputation and therefore was able to conduct his business without negative consequences.[66]

The main reason that Parker was able to escape consequences was the idea of “social credit” and social bonds between merchants. Once he arrived in Britain, no one knew of his history of evading his debts, so people had no reason to distrust him about his financial endeavors.[67] In essence, his social reputation worked similarly to a modern-day credit score. If one has a “good score”, it’s much easier for that person to do business with others and eventually scam more innocent customers and fellow merchants out of their money. But by keeping people accountable by better communicating between economies, people are able to keep shady merchants such as Parker from playing the system. But because he was able to escape, he was able to manipulate more people. Cutterham explains further in his article that while in London and Amsterdam, Parker “became a substantial participant in an emerging international financial market.” [68] He was able to make powerful connections within this new environment, with one of the most influential people he met being the ambassador to the Netherlands from the United States, John Adams. Adams served in this capacity between the years of 1778 and 1788, but of course would become even more notable as the second President of the United States, starting in 1797.[69]

The fact that Parker was able to acquaint himself with such powerful and intelligent people goes to show that major reforms needed to be made in the system if prosperity was to be achieved. Network formations during this period were essential to the bonds between merchants. Family businesses within communities were common, but it was fundamentally clear that wider geographical networks were required to sustain larger flows of income.[70]

In the nineteenth century, merchants and merchant houses played a role in opening up China and the Pacific to Anglo-American trade interests. Note for example Jardine Matheson & Co. and the merchants of New South Wales. Other merchants profited from natural resources (the Hudson's Bay Company theoretically controlled much of North America, names like Rockefeller and Nobel dominated trade in oil in the US and in the Russian Empire), while still others made fortunes from exploiting new inventions – selling space on and commodities carried by railways and steamships.

In fully planned economies of the 20th century, planners replaced merchants in organising the distribution of goods and services.[71] However, merchants, increasingly labelled with euphemisms such as "industrialists", "businessmen", "entrepreneurs" or "oligarchs",[72] continue their activities in the 21st century.[73]

In art

[edit]Elizabeth Honig has argued that artists, especially the painters of Antwerp, developed a fascination with merchants from the mid-16th century.[74] The wealthier merchants also had the means to commission artworks with the result that individual merchants and their families became important subject matter for artists. For instance, Hans Holbein the younger painted a series of portraits of Hanseatic merchants working out of London's Steelyard in the 1530s.[75] These included including Georg Giese of Danzig; Hillebrant Wedigh of Cologne; Dirk Tybis of Duisburg; Hans of Antwerp, Hermann Wedigh, Johann Schwarzwald, Cyriacus Kale, Derich Born and Derick Berck.[76] Paintings of groups of merchants, notably officers of the merchant guilds, also became subject matter for artists and documented the rise of important mercantile organisations.[citation needed]

In 2022, Dutch photographer Loes Heerink spend hours on bridges in Hanoi to take pictures of Vietnamese street Merchants. She published a book called Merchants in Motion: the art of Vietnamese Street Vendors.[77]

-

A Jewish merchant and his family by Paolo Uccello 1465-1469

-

The Arnolfini Portrait, believed to be of Italian merchant, Giovanni de Nicolao Arnolfini with his wife, by Jan van Eyck, c. 1434

-

Lorenzo de' Medici, merchant, Florentine bust, 14th or 15th century

-

Mathias Mulich (1470-1528), Merchant in Lübeck, by Jacob Claesz van Utrecht, c. 1522

-

Portrait of Anton Fugger by Hans Maler zu Schwaz, c. 1525

-

Portrait of George Gisze, the merchant, by Hans Holbein the Younger, c 1532

-

Portrait of a member of the Wedigh merchant family by Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1532

-

The Hanseatic merchant, Cyriacus Kale, by Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1533

-

A Hanseatic merchant, by Hans Holbein the Younger, c 1538

-

Portrait of a Merchant by Corneille de Lyon, c. 1541

-

Sir Thomas Gresham by Anthonis Mor, c. 1560.

-

Cornelis van der Geest, merchant of Antwerp, by Anthony van Dyck, c. 1620

-

Portrait of Nicolaes van der Borght, merchant of Antwerp by Van Dyk, 1625–35

-

Portrait of the cloth merchant, Abraham del Court and his wife Maria de Keerssegieter by Bartelmeus van der Helst, c. 1654

-

Frederick Rihel, a merchant on horseback by Rembrandt, c. 1663

-

Portrait of Amsterdam merchant, Cornelis Nuyts (1574-1661) by Jürgen Ovens

-

Portrait of Joshua van Belle, merchant in Spain by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, c. 1670

-

Portrait of Pieter Cnoll, senior merchant of Batavia, with family, by Jacob Janz Coeman, c.1655

-

The Merchant by Abraham van Strij c. 1800

-

Caspar Voght, German merchant, 1801 by Jean-Laurent Mosnier

-

Joshua Watson, English wine merchant, 1863

-

The Carpet Merchant by Jean-Léon Gérôme, c 1887

-

Merchant Sytov by anonymous (Rybinsk museum), mid-19th century

-

Governors of the Wine Merchant's Guild by Ferdinand Bol, c. 1680

-

The Syndics of the Drapers' Guild by Rembrandt, c. 1662

-

Four officers of the Amsterdam Coopers and wine-rackers Guild by Gerbrand Jansz van den Eeckhout, c. 1660

-

Reception of Jan Karel de Cordes at the guild hall by Balthasar van den Bossche, c.1711

In architecture

[edit]Although merchant halls were known in antiquity, they fell into disuse and were not reinvented until Europe's medieval period.[78] During the 12th century, powerful guilds which controlled the way that trade was conducted were established and were often incorporated into the charters granted to market towns. By the 13th and 14th centuries, merchant guilds had acquired sufficient resources to erect guild halls in many major market towns.[79] Many buildings have retained the names derived from their former use as the home or place of business of merchants:[citation needed]

-

The Merchant's House, Kirkcaldy, Scotland

-

Merchant Tower, Kentucky, USA

-

Medieval merchant's house, Southampton, England

-

Tudor Merchant's Hall, Southampton, England

-

Drapers' Hall, Coventry, England

-

The Blacksmiths' Guild Hall, Venice, Italy

-

Shoemakers' Guild Hall, Venice, Italy

-

Brodhaus, Bakers' Guild, Einbeck, Germany

-

Knochenhaueramtshaus, Butcher's guild hall, Hildesheim, Germany

-

The Butcher's Hall, Antwerp, Belgium

-

The Hanseatic League Building, Antwerp, 16th century

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- References

- ^ "Definition of MERCHANT". www.merriam-webster.com. 24 June 2024. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "merchant | Etymology of merchant by etymonline". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, 2013. mer‧chant

- ^ Demirdjian, Z. S., "Rise and Fall of Marketing in Mesopotamia: A Conundrum in the Cradle of Civilization," In The Future of Marketing's Past: Proceedings of the 12th Annual Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing, Leighton Neilson (ed.), CA, Longman, Association for Analysis and Research in Marketing, 2005

- ^ Rahul Oka & Chapurukha M. Kusimba, "The Archaeology of Trading Systems, Part 1: Towards a New Trade Synthesis," The Archaeology of Trading Systems, Part 1: Towards a New Trade Synthesis," Journal of Archaeological Research, Vol. 16, pp 339–395

- ^ Bar-Yosef, O., "The Upper Paleolithic Revolution," Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 31, pp 363–393

- ^ Alberti, M. E., "Trade and Weighing Systems in the Southern Aegean from the Early Bronze Age to the Iron Age: How Changing Circuits Influenced Global Measures," in Molloy, B. (ed.), Of Odysseys and Oddities: Scales and Modes of Interaction Between Prehistoric Aegean Societies and their Neighbours, [Sheffield Studies in Aegean Archaeology], Oxford, Oxbow, (E-Book), 2016

- ^ Bintliff, J., "Going to Market in Antiquity," In Stuttgarter Kolloquium zur Historischen Geographie des Altertums, Eckart Olshausen and Holger Sonnabend (eds), Stuttgart, Franz Steiner, 2002, pp 209–250

- ^ Shaw, E.H., “Ancient and Medieval Marketing," Chapter 2 in: Jones, D. G. B. and Tadajewski, M., The Routledge Companion to Marketing History, Routledge, 2016, pp 23–24

- ^ Olshausen, Eckart; Sonnabend, Holger (2002). Stuttgarter Kolloquium zur Historischen Geographie des Altertums, 7, 1999: zu Wasser und zu Land : Verkehrswege in der antiken Welt (in German). Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-08053-8.

- ^

Parker, John Henry (1876). "The Other Forums". The Forum Romanum. Oxford: James Parker & Company. p. 42. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

The Forum Boarium was the cattle-market or Smithfield of ancient Rome [...].

- ^ Coleman, P., Shopping Environments, Elsevier, Oxford, 2006, p. 28

- ^

Shaw, Eric H. (2016). "2: Ancient and medieval marketing". In Jones, D.G. Brian; Tadajewski, Mark (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Marketing History. Routledge Companions. London: Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 9781134688685. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

Perhaps the only substantiated type of retail marketing practice that evolved from Neolithic times to the present was the itinerant tradesman (also known as peddler, packman or chapman). These forerunners of travelling salesmen roamed from village to village bartering stone axes in exchange for salt or other goods (Dixon, 1975).

- ^ Stabel, P., "Guilds in Late Medieval Flanders: myths and realities of guild life in an export-oriented environment," Journal of Medieval History, vol. 30, 2004, pp 187–212

- ^ Rawlinson, G., History of Phoenicia, Library of Alexandria, 1889

- ^ Cartwright, M., "Trade in the Phoenician World", World History Encyclopedia, 1 April 2016

- ^ Daniels (1996) p. 94–95.

- ^ "Discovery of Egyptian Inscriptions Indicates an Earlier Date for Origin of the Alphabet". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ Oka, R. and Kusimba, C.M., "The Archaeology of Trading Systems, Part 1: Towards a New Trade Synthesis," The Archaeology of Trading Systems, Part 1: Towards a New Trade Synthesis," Journal of Archaeological Research, Vol. 16, p. 359

- ^ Tchernia, A., The Romans and Trade, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2016, Ch 1

- ^ Ashraf, A., "Bazaar-Mosque Alliance: The Social Basis of Revolts and Revolutions," International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, Vol. 1, No. 4, 1988, pp. 538–567, Stable URL: JSTOR 20006873, p. 539

- ^ "Decameron Web – Society". Brown.edu. Archived from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ Barnish, S.J.B. (1989) "The Transformation of Classical Cities and the Pirenne Debate", Journal of Roman Archaeology, Vol. 2, p. 390.

- ^ Curtis, R.I., "A Personalized Floor Mosaic from Pompeii", American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 88, No. 4 (October 1984), DOI: 10.2307/504744, pp. 557–566, Stable URL: JSTOR 504744

- ^ Bintliff, J., "Going to Market in Antiquity," In Stuttgarter Kolloquium zur Historischen Geographie des Altertums, Eckart Olshausen and Holger Sonnabend (eds), Stuttgart, Franz Steiner, 2002, p. 229, https://books.google.com/books?id=IAMK1952av4C : "The kind of model that Morley and other specialists in Greco-Roman marketing have been developing [...] sees the local market-town as primarily serving local peasantry. Here they unload their small surplus and purchase minor amounts of farm equipment and luxuries for their barns and homes; some of their needs are already met through travelling pedlars and non-urban periodic fairs held at long intervals. Major producers – the great estates – would be attractive enough foci for merchants to consider travelling directly to purchase commercially-focussed harvests 'at the farm gate', and some landowners were wealthy enough to handle their own distribution to urban markets in the country of production and even to other countries. These latter processes are documented both in the ancient sources and archaeological case-studies."

- ^ Millar, F., "The World of the Golden Ass", Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 71, 1981, pp. 63–67

- ^ McLaughlin, R., The Roman Empire and the Silk Routes: The Ancient World Economy and the Empires of Parthia, Central Asia and Han China,South Yorkshire, Pen and Sword Books, 2016

- ^ McLaughlin, R., The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean: The Ancient World Economy and the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia and India, South Yorkshire, Pen and Sword Books, 2014, p. 135: "The pure-white marble that was quarried in southern Arabia had a fine crystalline texture and Roman merchnts took aboard this heavy material as ballast to stabilise their ships. On their return to the empire, this valuable marble was sold to stoneworkers and carved into elegant unguent jars that resembled radiant alabaster."

- ^ McLaughlin, R., The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean: The Ancient World Economy and the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia and India, South Yorkshire, Pen and Sword Books, 2014, p. 222: "A further Roman criticism of eastern trade was that it created a consumer market for expensive foreign goods that were wastefully extravagant and ultimately unnecessary. [...] During the Julio-Claudian era aristocratic families competed for political status and prestige through the ostentatious display of wealth."

- ^ Bintliff, J., "Going to Market in Antiquity", In Stuttgarter Kolloquium zur Historischen Geographie des Altertums, Eckart Olshausen and Holger Sonnabend (eds), Stuttgart, Franz Steiner, 2002, p. 224

- ^ "Merchant guild | Medieval, Craftsmen, Guilds | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 13 June 2024. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ Epstein, S.A, Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe, University of North Carolina Press, 1991, pp 50–100

- ^ Casson, M. and Lee, J., "The Origin and Development of Markets: A Business History Perspective," Business History Review, Vol 85, Spring, 2011, doi:10.1017/S0007680511000018, pp 22–26

- ^ Clerici, L., "Le prix du bien commun. Taxation des prix et approvisionnement urbain (Vicence, XVIe-XVIIe siècle)" [The price of the common good. Official prices and urban provisioning in sixteenth and seventeenth century Vicenza] in I prezzi delle cose nell’età preindustriale /The Prices of Things in Pre-Industrial Times, [forthcoming], Firenze University Press, 2017.

- ^ "Merchant Adventurers" in Encyclopædia Britannica, Online Library Edition, 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Braudel, F. and Reynold, S., The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism, 15th to 18th Century, Berkeley CA, University of California Press, 1992

- ^ Salomón, F., "Pochteca and mindalá: a comparison of long-distance traders in Ecuador and Mesoamerica," Journal of the Steward Anthropological Society, Vol. 1–2, 1978, pp 231–246

- ^ Rebecca M. Seaman, ed. (27 August 2013). Conflict in the Early Americas: An Encyclopedia of the Spanish Empire's Aztec, Incan and Mayan Conquests. Abc-Clio. p. 375. ISBN 9781598847772.

- ^ Querciolo Mazzonis (2007). Spirituality, Gender, and the Self in Renaissance Italy: Angela Merici and the Company of St. Ursula (1474–1540). CUA Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0813214900.

- ^ King, Margaret L. (2016). A Short History of the Renaissance in Europe. University of Toronto Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-1487593087.

- ^ Dion C. Smythe (2016). Strangers to Themselves: The Byzantine Outsider: Papers from the Thirty-Second Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, University of Sussex, Brighton, March 1998. Routledge. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-1351897808.

- ^ Jeannie Labno (2016). "3". Commemorating the Polish Renaissance Child: Funeral Monuments and their European Context. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317163954.

- ^ R. S. Alexander (2012). Europe's Uncertain Path 1814-1914: State Formation and Civil Society. John Wiley & Sons. p. 82. ISBN 978-1405100526.

- ^ Southerton, Dale, ed. (15 September 2011). Encyclopedia of Consumer Culture. SAGE Publications (published 2011). p. xxx. ISBN 9781452266534. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Jones, C. and Spang, R., "Sans Culottes, Sans Café, Sans Tabac: Shifting Realms of Luxury and Necessity in Eighteenth-Century France," Chapter 2 in Consumers and Luxury: Consumer Culture in Europe, 1650–1850 Berg, M. and Clifford, H., Manchester University Press, 1999; Berg, M., "New Commodities, Luxuries and Their Consumers in Nineteenth-Century England," Chapter 3 in Consumers and Luxury: Consumer Culture in Europe, 1650–1850 Berg, M. and Clifford, H., Manchester University Press, 1999

- ^ Jonathan Dewald (1996). The European Nobility, 1400-1800. Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 052142528X.

- ^ Minto, W., Daniel Defoe, Tredition Classics, [Project Gutenberg ed.], Chapter 10

- ^ Richetti, J., The Life of Daniel Defoe: A Critical Biography, Malden, MA., Blackwell, 2005, 2015, pp 147–49 and 158-59

- ^ Backscheider, P.R., Daniel Defoe: His Life, Baltimore, Maryland, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

- ^ Bakhchinyan, Artsvi (2017). "The Activity of Armenian Merchants in International Trade" (PDF). Regional Routes, Regional Roots? Cross-Border. Patterns of Human Mobility in Eurasia. Hokkaido Slavic-Eurasian Research Center. pp. 23–29. abstract of book chapter

- ^ Vanneste, R., Global Trade and Commercial Networks: Eighteenth-Century Diamond Merchants, London, Pickering and Chatto, 2011, ISBN 9781848930872

- ^ McKendrick, N., Brewer, J. and Plumb . J.H., The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth Century England, London, 1982.

- ^ Cox, N.C. and Dannehl, K., Perceptions of Retailing in Early Modern England, Aldershot, Hampshire, Ashgate, 2007, pp 155–59

- ^ McKendrick, N., Brewer, J. and Plumb . J.H., The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth Century England, London, 1982.

- ^ Tadajewski, M. and Jones, D.G.B., "Historical research in marketing theory and practice: a review essay", Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 30, No. 11-12, 2014 [Special Issue: Pushing the Boundaries, Sketching the Future], pp 1239–1291.

- ^ Flanders, Judith (10 January 2009). "Opinion | They Broke It". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ Drake, D., "Dinnerware & Cost Accounting? The Story of Josiah Wedgwood: Potter and Cost Accountant," HQ Financial Views, Volume I, 1 May–July 2005, pp 1–3

- ^ Applbaum, K., The Marketing Era: From Professional Practice to Global Provisioning, Routledge, 2004, p. 126-127

- ^ McKendrick, N., Brewer, J. and Plumb . J.H., The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth Century England, London, 1982.

- ^ Savitt, R., "Looking Back to See Ahead: Writing the History of American Retailing", in Retailing: The Evolution and Development of Retailing, A. M. Findlay, Leigh Sparks (eds), pp 138–39.

- ^ Smail, John (July 2005). "Credit, Risk, and Honor in Eighteenth-Century Commerce". Journal of British Studies. 44 (3): 439–456. doi:10.1086/429706. ISSN 0021-9371.

- ^ Stobart, Jon (1 September 2005). "Information, Trust and Reputation: Shaping a merchant elite in early 18th‐century England". Scandinavian Journal of History. 30 (3–4): 298–307. doi:10.1080/03468750500295786. ISSN 0346-8755.

- ^ Stobart, Jon (1 September 2005). "Information, Trust and Reputation: Shaping a merchant elite in early 18th‐century England". Scandinavian Journal of History. 30 (3–4): 298–307. doi:10.1080/03468750500295786. ISSN 0346-8755.

- ^ Stobart, Jon (1 September 2005). "Information, Trust and Reputation: Shaping a merchant elite in early 18th‐century England". Scandinavian Journal of History. 30 (3–4): 298–307. doi:10.1080/03468750500295786. ISSN 0346-8755.

- ^ Cutterham, Tom (2018). ""A Very Promising Appearance": Credit, Honor, and Deception in the Emerging Market for American Debt, 1784–92". The William and Mary Quarterly. 75 (4): 623–650. ISSN 1933-7698.

- ^ Cutterham, Tom (2018). ""A Very Promising Appearance": Credit, Honor, and Deception in the Emerging Market for American Debt, 1784–92". The William and Mary Quarterly. 75 (4): 623–650. ISSN 1933-7698.

- ^ Cutterham, Tom (2018). ""A Very Promising Appearance": Credit, Honor, and Deception in the Emerging Market for American Debt, 1784–92". The William and Mary Quarterly. 75 (4): 623–650. ISSN 1933-7698.

- ^ Cutterham, Tom (2018). ""A Very Promising Appearance": Credit, Honor, and Deception in the Emerging Market for American Debt, 1784–92". The William and Mary Quarterly. 75 (4): 623–650. ISSN 1933-7698.

- ^ Cutterham, Tom (2018). ""A Very Promising Appearance": Credit, Honor, and Deception in the Emerging Market for American Debt, 1784–92". The William and Mary Quarterly. 75 (4): 623–650. ISSN 1933-7698.

- ^ Stobart, Jon (1 September 2005). "Information, Trust and Reputation: Shaping a merchant elite in early 18th‐century England". Scandinavian Journal of History. 30 (3–4): 298–307. doi:10.1080/03468750500295786. ISSN 0346-8755.

- ^

Tang Lixing (14 December 2017). Merchants and Society in Modern China: From Guild to Chamber of Commerce. China Perspectives. Routledge (published 2017). ISBN 9781351612968. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

We see the permutation and extension of the traditional economic elements in highly planned economy. The anti-commerce policy reached to such an extreme that merchants were dismissed as the capitalist heresy.

- ^ Graph of proportionate terminology usage

- ^ Book by Kim Kiyosaki and Robert Kiyosaki. The Business of the 21st Century.

- ^ Honig, E.A., Painting & the Market in Early Modern Antwerp, Yale University Press, 1998, pp 6–10

- ^ Fudge, J.F., Commerce and Print in the Early Reformation, Brill, 2007, p.110

- ^ Holman, T.S., "Holbein's Portraits of the Steelyard Merchants: An Investigation," Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol. 14, 1980, pp 139–158

- ^ "Merchants in Motion". Loes Heerink. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ Gelderblom, O. and Grafe, E., "The Persistence and Decline of Merchant Guilds: Re-thinking the Comparative Study of Commercial Institutions in Pre-modern Europe," [Working Paper], Yale University, 2008

- ^ Epstein S.A, Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe, University of North Carolina Press, 1991, pp 50–100

Sources and further reading

[edit]- Adams Julia. The Familial State. Ruling Families and Merchant Capitalism in Early Modern Europe (Cornell University Press, 2005)

- Braudel, F. The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism, 15th to 18th Century (U of California Press, 1992)

- Burset, Christian R. "Merchant courts, arbitration, and the politics of commercial litigation in the eighteenth-century British Empire." Law and History Review 34.3 (2016): 615–647. online

- Casson, Mark. The entrepreneur: An economic theory (Rowman & Littlefield, 1982). Influential scholarly survey

- Enciso, Agustín González. "The merchant and the common good: social paradigms and the state’s influence in Western history." in The Challenges of Capitalism for Virtue Ethics and the Common Good (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2016).

- Julien, Pierre-André, ed. The state of the art in small business and entrepreneurship (Routledge, 2018).

- Lindemann, Mary. The Merchant Republics—Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Hamburg, 1648–1790 (Cambridge UP, 2015)

- Marsden, Magnus, and Vera Skvirskaja. "Merchant identities, trading nodes, and globalization: Introduction to the Special Issue." History and Anthropology 29.sup1 (2018): S1-S13. online

- Smith, Adam, "An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations" (Bantam Classics, Annotated Edition, 4 March 2003) ISBN 978-0553585971

- Origo, Iris. The Merchant of Prato: Daily Life in a Medieval Italian City (Penguin UK, 2017).

- Outhwaite, R. B. "Merchants and Gentry in North-East England, 1650–1830: The Carrs and the Ellisons." English Historical Review 115.462 (2000): 729–729.

- Persaud, Alexander. "Indian Merchant Migration within the British Empire." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. (2020)

- Smith, Edmond. Merchants: The Community That Shaped England's Trade and Empire, 1550-1650 (Yale University Press, 2021) online review

- Thrupp, Sylvia L. (1989). The Merchant Class of Medieval London, 1300–1500. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-06072-6.

- Williams, E. N. "Our Merchants Are Princes": The English Middle Classes In The Eighteenth Century" History Today (Aug 196) 2, Vol. 12 Issue 8, pp548–557.