Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

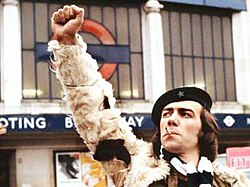

Citizen Smith

View on Wikipedia

| Citizen Smith | |

|---|---|

| |

| Created by | John Sullivan |

| Starring | Robert Lindsay Mike Grady Cheryl Hall Hilda Braid Peter Vaughan Tony Steedman Tony Millan George Sweeney Stephen Greif David Garfield |

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

| Original language | English |

| No. of series | 4 |

| No. of episodes | 30 (list of episodes) |

| Production | |

| Running time | 30 minutes |

| Original release | |

| Network | BBC1 |

| Release | 12 April 1977 – 31 December 1980 |

Citizen Smith is a British television sitcom written by John Sullivan, first broadcast from 1977 to 1980.[1]

It starred Robert Lindsay as Walter Henry "Wolfie" Smith,[2] a young Marxist[3] "urban guerrilla" in Tooting, south London, who is attempting to emulate his hero Che Guevara.[4] Wolfie is a reference to the Irish revolutionary Wolfe Tone, who used the pseudonym "Citizen Smith" in order to evade capture by the Dublin Castle administration. Wolfie is the self-proclaimed leader of the revolutionary Tooting Popular Front (the TPF, merely a small bunch of his friends), the goals of which are "Power to the People" and "Freedom for Tooting".

Wolfie dresses in a stereotypical fashion for rebellious students of the period: logoed T-shirt, denim jeans, Afghan coat, and black beret. He supports Fulham and occasionally wears a Fulham scarf. He rides a scooter and lives in the attic room at his girlfriend's parents’ house, and constantly clashes with her over-protective father.

Cast

[edit]- Robert Lindsay as Walter Henry "Wolfie" Smith

- Mike Grady as Ken Mills

- George Sweeney as Speed (Anthony "Speed" King)

- Tony Millan as Tucker

- Cheryl Hall as Shirley Johnson (series 1–2)

- Hilda Braid as Florence Johnson, Shirley's mother

- Artro Morris as Charles Johnson, Shirley's father (pilot episode)

- Peter Vaughan/Tony Steedman as Charlie Johnson, Shirley's father (series 1–2) and (series 3–4; 1980 Christmas special)

- Stephen Greif as Harry Fenning (series 1–3)

- David Garfield as Ronnie Lynch (series 4; 1980 Christmas special)

- Susie Baker as Mandy Lynch (series 4; 1980 Christmas special)

- Anna Nygh as Desiree, Speed's girlfriend (series 1–2)

- John Tordoff as policeman, Brian Tofkin (series 3-4)

History

[edit]John Sullivan became a scenery shifter at the BBC in 1974[5] because of his desire to write a sitcom outline he had called Citizen Smith; fearing rejection if he sent the idea in, he decided it would be better to get a job, any job, at the BBC, learn more about the business and then meet someone who would actually take notice of his as yet unwritten script. After he approached producer Dennis Main Wilson, the first Citizen Smith script was written. Main Wilson loved the script, and saw the potential for a series; it was put into production almost immediately as a pilot for Comedy Special — a showcase for new talent, which had succeeded Comedy Playhouse — under the title Citizen Smith. The pilot was a success, and four series and a Christmas special were produced between 1977 and 1980.

It has been claimed that the "Tooting Popular Front" — fictionally based near to writer John Sullivan's childhood home of Balham — was partly inspired by a real-life fellow-South London far-left group, the Brixton-based Workers' Institute of Marxism-Leninism-Mao Tsetung Thought.[6] The group's activities were reported in The Times' diary of April 1977,[7] the same month the pilot episode of Citizen Smith was broadcast.[8]

Opening titles

[edit]The opening titles of each episode of the first two series always began with Wolfie emerging from Tooting Broadway Underground station, followed by a shot of him kicking a can across a bridge until he is in close up, accompanied by a background rendition of the socialist anthem The Red Flag. They always ended with him shouting "Power to the People", resulting in awkward consequences such as waking a sleeping baby or causing a vehicle to crash. From the third series, the shots of Wolfie on the bridge were replaced with on-screen clips of other cast members and their names, rather than just the list of names that had been used previously, and the reactions to Wolfie's shout were dropped entirely. Series 4 had a new title sequence, which began with Tucker's van driving past Tooting Broadway tube station with "The Revolution is Back" painted on it. The rest of the credits were backed by clips from the last episode of series three, "The Glorious Day", and Wolfie's shout is heard, but he is not seen.

Plot

[edit]Series 1

[edit]From episode three, "Abide with Me", Wolfie Smith (Robert Lindsay) lives, with his religious, teetotal friend Ken Mills (Mike Grady), in a flat in the house of his girlfriend's family — Shirley Johnson (Cheryl Hall, at the time Lindsay's wife); her affable but naïve mother, Florence, who mistakenly calls Wolfie "Foxy"; and her strict, right-wing father, Charlie, who disapproves of Smith's lifestyle and refers to him as a "flaming yeti" or "Chairman Mao". Shirley considers herself engaged to Wolfie, on account of a fake crocodile tooth necklace he gave her after she was asked when they would get engaged.

Other regular characters in the series are the other "urban guerrillas": Tucker (married to the ever-pregnant but never-seen June); Speed, the TPF's Warlord, and his girlfriend Desiree; and local gangster publican Harry Fenning (played by Stephen Greif), who refers to Wolfie as "Trotsky". Wolfie and the TPF frequent Harry's pub, The Vigilante, and are at times menaced by Harry's hired muscle Floyd and Cyril (played by Dana Michie and Barry Hayes), who are referred to by Florence as "Mr Fenning's foster children".

The closest Wolfie comes to legitimate political office is contesting the Tooting North constituency as the TPF candidate at a parliamentary by-election, whose election night declaration is televised; however, he gains only six votes, losing to the Conservative candidate David West. He and the gang attempt to kidnap the new MP from a victory celebration, only to mistakenly capture Harry Fenning (who was leaving the Conservative Club during the occasion) instead (Episode 6 - "The Hostage").

Series 2

[edit]Series two consists of six episodes; however, owing to industrial action at the BBC on 22 December 1978, one episode ("Spanish Fly") had to be rescheduled as a special in August 1979.

Series 3

[edit]"The Glorious Day", which Wolfie had always been plotting, comes at the end of the third series, in an episode of the same name, in which the Tooting Popular Front "liberate" a Scorpion tank and use it to invade the Houses of Parliament, only to find the place empty, owing to a parliamentary recess. During the TPF's "annual manoeuvres" on Salisbury Plain, Wolfie, Ken, Tucker and Speed decide to camp down after an evening of heavy drinking; unbeknownst to them, they are in the middle of a military live firing area. During the night, the Army hold an exercise, and the Scorpion is "abandoned" by its crew after being declared "knocked out" by a "landmine" during a training exercise. When Wolfie and his comrades discover this, Wolfie comes up with his revolutionary plan. Speed states that he learned to drive a Scorpion during his time in the Territorial Army, at which point the group steal it and drive it back to London.

On returning, they hide it in Charlie Johnson's garage. Charlie comes home from work and opens the garage door to park his car. Curious as to the purpose of the Scorpion parked amongst the garden tools, he climbs down inside and accidentally steps on the machine-gun fire button. The result is that their neat garden is raked with heavy machine-gun fire, narrowly missing his wife Florence who is hanging out the washing, and annihilating their garden gnomes. This episode also includes a new song from John Sullivan and sung by Robert Lindsay — "We are the TPF. We are the People."

Series three consists of seven episodes.

Series 4

[edit]The series began with Wolfie and company being paroled, a brief flirtation at being pop stars on the back of their "fame" ended in disaster. While the TPF have been away, a new gangster, Ronnie Lynch, has usurped Fenning's position in Tooting, including his old pub. Wolfie hates him more than he did Fenning, and after various run-ins with Lynch (who constantly refers to Wolfie as "Wally"), the series was concluded in the penultimate episode, with Wolfie fleeing Tooting to escape a £6,000 contract put on his head by Ronnie Lynch after Lynch had caught Wolfie in his wife Mandy's bedroom. Closing with a shot mirroring the opening credits, Wolfie is seen entering Tooting Broadway tube station. Series four consisted of seven episodes and a Christmas special, "Buon Natale", in which Wolfie and Ken ride to Rimini on Wolfie's Lambretta to visit Shirley for the festive period, only to find that she has become romantically involved with an Italian named Paolo. This episode was shown after the series officially ended, but is set before the events of the last episode.

Notes

[edit]- Some sources erroneously name the pilot as "A Roof Over My Head", which was actually the title of the previous week's Comedy Special, written by Barry Took (which also led to a series).

- In the penultimate episode, Wolfie's full name was revealed as Walter Henry Smith – W H Smith.

- Early episodes state that there are six members of the Tooting Popular Front, but only four appear onscreen. In series 3 Wolfie says that two founder members have left the TPF: Dave the Nose (the TPF's Foreign Secretary) has emigrated, and Reg X (a Black Panther) is playing second oil drum in a steel band at Butlins.

- In the 1980 Christmas special, the Italianate village of Portmeirion in North Wales stood in for Rimini, with other locations in the vicinity used for other parts of their journey across Europe.

- The 1980 Christmas special featured the Beatles' song "Here Comes the Sun", which has been replaced on subsequent DVD releases, owing to licensing issues.

- In the original television broadcast of the episode, "Working Class Hero" the music that accompanies Wolfie's commute on his first day at work is "Carry That Weight" from the Beatles' Abbey Road album. This too was substituted on the DVD issue, with a nondescript jazz tune.

- The end title theme was written by John Sullivan and sung by Robert Lindsay, and is called "The Glorious Day".

Episodes

[edit]The show aired between 1977 and 1980 in four seasons.[9] In 2015, it was announced that the sitcom would be revived, with Robert Lindsay reprising the role of Wolfie Smith.[9]

Novel

[edit]Citizen Smith, a novelisation of the first series written by Christopher Kenworthy, was published by Universal books, London in 1978.

Mooted revival

[edit]In 2015, Lindsay was reported as saying he was very keen to reprise the role of Wolfie Smith, particularly with the rise of Jeremy Corbyn.[10] However, it was also reported that the family of the by then deceased Sullivan, who own the rights, did not want to bring it back.[11]

Home media

[edit]Playback released two DVD volumes of Citizen Smith, each with two series. Series one and two (including the pilot) were released in 2003 followed by series three and four later that year.

Only two episodes have actually been cut: "Changes" – where Tucker and Wolfie miming to the Beatles tracks "Till There Was You" (and Tucker's line "I think they like us.") and "Help!" have been cut from the scene where Tucker serenades June; and "Prisoners" – where a short scene of Wolfie singing along to the Beatles track "She Loves You", which comes in between the shot of Speed throwing stones at Wolfie's window and the shot of the window breaking, has also been cut.

Cinema Club bought the rights to the series, and later released all four series in a complete series set on 17 July 2017.

In Spring 2026, Fabulous Films is scheduled to release Citizen Smith: The Complete Series (1977–1980) on Blu-ray for the first time. The four-disc set features a new restoration from the surviving original tape elements, with previously removed scenes reinstated using revised music.[12]

References

[edit]This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2009) |

- Steve Clark The Only Fools and Horses Story, pp26–28, ISBN 0-563-38445-X, first published 1998,

- Mark Lewisohn Radio Times Guide to TV Comedy, (A Roof Over My Head, p172, 658.) ISBN 0-563-48755-0, reprinted 2003.

- Universal/Playback DVD Series 1/2 and Series 3/4. 2003.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "BFI Screenonline: Citizen Smith (1977-80)". screenonline.org.uk. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Barnett, David (20 March 2017). "We remember Citizen Smith fondly but is there a place for him in today's politics?". The Independent. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ "The British Comedy Guide". British Comedy Guide. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ "Citizen Smith (1977)". BFI. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "John Sullivan | A Television Heaven Biography". Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ Catchpole, Charlie (1 December 2013). "Flashback to the 1970s with far left sects, Maoists, Comrade Bala and Monty Python". Mirror.co.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "Maoist 'slaves': Combating the fascist state in Brixton". weeklyworker.co.uk. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Citizen Smith" Citizen Smith: Pilot (TV Episode 1977) - IMDb, 12 April 1977, retrieved 12 August 2021

- ^ a b "Classic 1970s BBC comedy Citizen Smith set to return". The Independent. 11 September 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

- ^ "Classic 1970s BBC comedy Citizen Smith set to return". Independent.co.uk. 11 September 2015.

- ^ "Citizen Smith won't be coming back". Digital Spy. 11 September 2015.

- ^ Renwick, Lio (15 February 2026). "Citizen Smith: The Complete Series (1977-1980) Blu-ray Box Set Coming This Spring from Fabulous Films". Physical Media News.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

External links

[edit]- Citizen Smith at BBC Online

- Citizen Smith at BBC Online Comedy Guide

- Citizen Smith at the BFI's Screenonline

- Citizen Smith at IMDb

- Citizen Smith at epguides.com

- Citizen Smith at British Comedy Guide

- Citizen Smith at British TV Resources

Citizen Smith

View on GrokipediaOverview

Premise and Format

Citizen Smith is a British television sitcom created and written by John Sullivan, broadcast on BBC One from 3 November 1977 to 31 December 1980 across four series comprising 22 episodes plus a pilot. The premise revolves around a small, self-proclaimed revolutionary organization in Tooting, South London, whose members espouse Marxist-Leninist ideals and plot the overthrow of the British government, only to be repeatedly thwarted by their own incompetence, laziness, and entanglement in petty domestic disputes. This setup satirizes the era's radical left-wing movements by depicting high-flown political rhetoric as disconnected from executable action, often resulting in absurd, inconsequential outcomes amid everyday banalities like unemployment and landlord troubles.[1][2][3] The series adheres to the conventional multi-camera sitcom format prevalent in British broadcasting during the late 1970s, featuring studio-audience laughter, static sets representing domestic and communal spaces, and episodes clocking in at around 30 minutes each. Narrative structure emphasizes episodic, self-contained stories driven by situational farce and interpersonal conflicts, where grandiose schemes dissolve into comedic chaos without advancing any tangible revolutionary progress. This format underscores a causal realism in the humor: ideological posturing fails not due to external oppression alone but primarily from internal flaws such as poor planning and motivational deficits, reflecting Sullivan's observational style drawn from real-life acquaintances.[6][7][8]Setting and Tone

is set primarily in Tooting, a working-class district in South London, where the protagonist Wolfie Smith and his comrades reside in a dilapidated squat. The series unfolds in the late 1970s, capturing the gritty urban environment of multi-ethnic neighborhoods amid Britain's economic stagnation, with high unemployment and decaying infrastructure reflecting the characters' precarious lifestyles.[2][1] The temporal context aligns with real historical upheavals, including the Winter of Discontent from November 1978 to February 1979, a period of widespread strikes by public sector workers protesting government wage controls amid inflation exceeding 8% annually. This backdrop of garbage piling in streets, unburied bodies, and disrupted services provides an ironic contrast to the characters' futile attempts at organized resistance, highlighting the disconnect between ideological fervor and practical chaos.[9][10] The overall tone employs light-hearted farce and observational satire, emphasizing slapstick mishaps and verbal wit over didactic messaging. Humor arises from the protagonists' self-deluded incompetence—such as botched heists or empty proclamations—rather than any endorsement of their Marxist rhetoric, underscoring the absurdity of utopian schemes clashing with everyday banalities like domestic squabbles and petty crime. This approach differentiates the series from somber political dramas by grounding critique in empirical depictions of human folly and group dynamics, avoiding romanticization of activism.[3][2]Cast and Characters

Principal Cast

Robert Lindsay led the principal cast as Walter "Wolfie" Smith, the unemployed, aspiring Marxist revolutionary heading the Tooting Popular Front, whose bombastic declarations of "Power to the People" belied his habitual laziness and repeated failures in organizing meaningful action.[1][11] Lindsay's portrayal, drawing on physical comedy and over-the-top zeal, emphasized the archetype of the performative ideologue more than a credible activist, amplifying the series' mockery of ideological posturing without practical follow-through.[12] Cheryl Hall portrayed Shirley Johnson, Wolfie's girlfriend and a voice of reluctant realism amid his schemes, appearing through the first two series until her character's departure.[12] Hall's performance grounded the satire by depicting Shirley's exasperation with Wolfie's delusions, highlighting the personal toll of unchecked revolutionary fervor on everyday relationships.[1] Mike Grady played Ken Mills, Wolfie's steadfast but pragmatic comrade in the TPF, often injecting caution or moral qualms into the group's hapless plots.[12] Grady's understated delivery contrasted Lindsay's flamboyance, underscoring the comedic futility of the group's dynamics through the lens of mismatched temperaments in pursuit of utopian goals.[1]Recurring Characters

Speed (portrayed by George Sweeney) and Tucker (Tony Millan) function as core members of the Tooting Popular Front (TPF), embodying the group's collective incompetence and shared illusions of grandeur that sustain its futile operations. Speed, styled as the TPF's "warlord" with a background in the Territorial Army, contributes bombastic aggression but delivers no tangible revolutionary progress, amplifying the satire on performative militancy devoid of strategic efficacy.[12][13] Tucker, perpetually distracted by marital issues and the unseen but ever-pregnant June, injects domestic banalities that deflate Wolfie Smith's ideological fervor, illustrating how personal entanglements erode group cohesion in nascent insurgent formations.[12][13] Family figures, such as Wolfie's mother (Hilda Braid as Mum) and father (Peter Vaughan in series 1–2, Tony Steedman in series 3–4), anchor the narrative in prosaic conservatism, their exasperation with Wolfie's unemployment and disruptions underscoring the chasm between radical rhetoric and household economic imperatives.[12] These parental roles depict a pragmatic worldview rooted in steady employment and social stability, which repeatedly exposes the TPF's schemes as incompatible with real-world familial and financial constraints.[13] Authority representatives like Harry Fenning (Stephen Greif), the Vigilante pub landlord and informal local enforcer, provide adversarial realism by intimidating the TPF over unpaid tabs and minor infractions, referring to Wolfie derisively as "Trotsky" while wielding de facto control in the community.[7][14] Fenning's opportunistic pragmatism contrasts sharply with the group's ideological posturing, highlighting how entrenched power structures—bolstered by economic leverage—neutralize disorganized radicalism without resorting to overt confrontation.[13] Together, these supporting roles delineate the TPF's internal delusions against external inertial forces, mirroring the structural reasons micro-revolutionary outfits historically dissipate through incompetence and isolation.[13]Production

Development and Pilot Episode

John Sullivan developed the concept for Citizen Smith in the mid-1970s, crafting a sitcom centered on a self-proclaimed revolutionary whose grandiose Marxist ideals clashed comically with everyday ineptitude, inspired by an acquaintance embodying the era's deluded urban activists who professed radicalism but achieved little beyond posturing.[7] This portrayal drew from the broader cultural landscape of 1970s Britain, where squatting collectives and fringe leftist groups often devolved into disorganized farce rather than effective change, a dynamic Sullivan observed and satirized without romanticizing. The BBC initially tested the material through a standalone pilot episode, aired on 12 April 1977 as part of its Comedy Specials strand, featuring Robert Lindsay in the lead role of Wolfie Smith alongside early cast members like Cheryl Hall as Shirley.[1] [15] Running approximately 30 minutes, the pilot highlighted Wolfie's futile attempts at subversion—from botched slogans to domestic squabbles—emphasizing the humor in deflating pretentious activism for a wider audience while retaining its core satirical bite on ideological posturing.[16] The episode's reception, marked by its depiction of revolutionary fervor as comically hollow, prompted the BBC to commission a full series later that year, transitioning from one-off trial to ongoing production without major tonal alterations that might have softened the critique of ineffectual radicalism. This greenlight reflected confidence in Sullivan's script as a fresh counterpoint to contemporaneous portrayals of activism, prioritizing empirical humor over idealized narratives.[7]Writing and Filming

John Sullivan wrote every episode of Citizen Smith single-handedly, crafting scripts that satirized the era's leftist revolutionary fervor through the lens of inept urban activists in south London.[1] His approach emphasized character-driven humor rooted in the mundane realities of 1970s Britain, including economic stagnation and social unrest, to underscore the disconnect between ideological posturing and practical outcomes.[2] This solo authorship allowed for consistent thematic continuity, with Wolfie Smith's bombastic declarations often clashing against everyday banalities like family dynamics and petty crime. Production utilized a multi-camera studio format at BBC Television Centre, the standard for BBC sitcoms of the period, enabling efficient capture of performances with three or more cameras to cover wide shots, close-ups, and audience reactions simultaneously. Episodes were recorded before a live studio audience, whose laughter provided authentic timing and energy, though some early broadcasts incorporated additional canned laughter for consistency.[2] Interior scenes, comprising the bulk of the action in flats, pubs, and meeting halls, were staged on soundstages to replicate Tooting's working-class environs. Exterior sequences were sparingly filmed on location in Tooting, south London, to authenticate the series' setting and capture the gritty urban backdrop of tube stations, high streets, and local pubs like those frequented by the Tooting Popular Front.[17] These shoots minimized disruption while grounding the satire in recognizable locales, such as Tooting Broadway, where opening credits featured Wolfie emerging from the Underground in beret and fatigues.[18] Across the four series, Sullivan refined the scripts to integrate raw political jabs with escalating farce, yielding progressively tighter comedic structures that prioritized ensemble interplay over overt manifesto-ranting, as reflected in viewer assessments of later episodes' enhanced humor.[3] This evolution maintained the core critique of futile activism while broadening appeal through relatable domestic absurdities, without diluting the underlying realism of failed ambitions amid Britain's turbulent late-1970s landscape.Cancellation and Behind-the-Scenes Challenges

The series concluded after four seasons, with the final regular episode airing on 3 July 1980, followed by a Christmas special in December of that year.[19] Lead actor Robert Lindsay elected to depart primarily to evade typecasting as the bumbling revolutionary Wolfie Smith and to explore broader opportunities in theatre and serious drama, having joined the Royal Exchange Theatre company post-series.[20] [1] This decision was precipitated by an altercation at a Greek restaurant, where fans' harassment amid the show's popularity—averaging 20 million weekly viewers—intensified personal pressures, ultimately straining Lindsay's relationship with creator John Sullivan.[20] The broader cultural context also contributed to the show's cessation, as the May 1979 general election victory of Margaret Thatcher's Conservatives marked a pivot away from the 1970s milieu of industrial unrest and leftist agitation that underpinned the satire's premise.[21] Wolfie Smith's inept Marxism, reflective of that decade's fading radical enthusiasms, lost immediacy in an era of economic stabilization and reduced tolerance for prolonged activist posturing.[21] Internally, the BBC's commissioning priorities evolved, with Sullivan transitioning to develop subsequent hits like Only Fools and Horses, signaling a shift toward fresh comedic formats amid the lead actor's unavailability.[22] These factors collectively precluded renewal, despite the series' initial strong audience draw.[20]Themes and Satire

Revolutionary Ideals and Ineptitude

Wolfie Smith, the protagonist of Citizen Smith, emulates Che Guevara through his beret-wearing persona, revolutionary posturing, and adoption of guerrilla rhetoric, positioning himself as the leader of the Tooting Popular Front (TPF), a fictional Marxist group aspiring to overthrow the British establishment.[23] The TPF's manifesto, encapsulated in slogans like "Power to the People" and "Freedom for Tooting," symbolizes an ideological framework detached from practical constraints, prioritizing abstract collectivist goals over individual incentives or economic realities such as resource scarcity and personal motivation.[24] This portrayal underscores a core tension: Smith's theoretical commitment to proletarian uprising consistently founders on his personal failings, revealing how high-minded doctrines falter when confronted with human limitations like laziness and poor planning.[23] The series recurrently depicts motifs of botched operations, grandiose orations that dissolve into farce, and interpersonal disarray within the TPF, illustrating the causal disconnect between collectivist prescriptions and the uncoordinated actions of flawed individuals.[25] These elements highlight ineptitude not as isolated errors but as systemic outcomes of ideologies that overlook first-order realities—such as the need for competence in execution or alignment with self-interested behavior—leading to inevitable collapse in everyday settings like suburban Tooting.[23] Smith's unemployment and petty criminality further exemplify this, as his revolutionary zeal yields no tangible progress, instead perpetuating a cycle of delusion and underachievement.[24] This fictional lens mirrors the disorganization observed in numerous small-scale Marxist factions in 1970s Britain, such as Maoist splinter groups, which often fragmented due to internal rivalries and operational inefficacy despite shared ideological aspirations.[26] Unlike more structured entities, these micro-movements echoed the TPF's pattern of rhetorical fervor without scalable action, providing an empirical parallel to the show's satire of how aspirational theory unravels amid practical disarray and human nature's resistance to enforced uniformity.[23] The depiction thus serves as a comedic yet pointed reflection of causal realism, where ideological purity proves insufficient against the mechanics of incompetence and misaligned incentives.[25]Critique of Left-Wing Activism

Citizen Smith satirizes 1970s left-wing activism through the Tooting Popular Front's (TPF) futile revolutionary posturing, where leader Wolfie Smith's ritualistic cries of "Power to the People," accompanied by a raised fist salute, serve as a recurring emblem of hollow rhetoric divorced from executable strategy.[27][28] The TPF, comprising just four inconsistent members, embodies the era's fragmented radical groups, whose grandiose manifestos against capitalism dissolve into petty squabbles and botched escapades, such as abortive bank raids or propaganda stunts that collapse under logistical ineptitude.[28] This depiction highlights causal disconnects in activist endeavors, where ideological fervor supplants empirical planning, yielding no systemic change despite professed commitments to proletarian uplift. The series underscores socialism's operational inefficiencies by portraying the TPF's collectivist ideals as undermined by free-rider problems and misaligned incentives; members prioritize personal distractions—like Wolfie's romantic pursuits or Speed's hypochondria—over collective discipline, mirroring how unchecked group dynamics erode productivity in centralized systems.[29] Such portrayals align with first-principles observations that human agency requires individual accountability, absent which moral hazards proliferate, as activists evade responsibility for outcomes while blaming external "imperialists."[29] In the 1970s British context, this resonates with the proliferation of minuscule Trotskyist factions that splintered without amassing viable power, their doctrinal purity yielding electoral irrelevance.[28] Defenders of the show's intent, including analyses from Sullivan's oeuvre, frame the satire as affectionate toward working-class dreamers, akin to how his later works gently rib entrepreneurial hustles without indicting capitalism itself, suggesting a balanced humanism over systemic takedown.[29][30] Yet, the relentless pattern of TPF debacles—culminating in surrenders to mundane realities like job demands or police scrutiny—exposes performative activism's sterility, privileging observable free-market adaptations that, post-1979, demonstrated resilience against the era's stagflation and strike-induced chaos.[31] The Winter of Discontent (1978–1979), with over 29 million lost workdays from union actions that paralyzed services without securing lasting gains, empirically validated this critique, as public revulsion propelled market-oriented reforms yielding economic recovery by the mid-1980s.[32] Left-leaning outlets often soft-pedal such parallels, attributing failures to external pressures rather than inherent flaws, though the satire's evidentiary thrust favors causal realism: revolutions demand not slogans, but mechanisms harnessing self-interest productively.[10]Social and Economic Realities

In Citizen Smith, the protagonist Wolfie Smith's persistent unemployment and aversion to gainful employment exemplify working-class stagnation rooted in personal idleness rather than external oppression, as he prioritizes revolutionary posturing over practical labor.[13][11] Wolfie, residing in his mother's home in Tooting, South London, embodies a lifestyle of minimal effort, often scheming petty crimes or idling with comrades while decrying capitalist exploitation, thereby linking his financial straits directly to behavioral choices.[33] This depiction avoids portraying poverty as an inevitable systemic force, instead attributing hardships to self-imposed inertia, such as Wolfie's refusal of available work in episodes like "Working Class Hero," where he ironically protests at a job center for employment rights while demonstrating no intent to seek it.[34] Family structures in the series further ground the satire in economic realism, contrasting Wolfie's indulgent, single-parent household—dependent on state support and lacking discipline—with the more pragmatic dynamics of Shirley Johnson's family. Shirley's father, Charlie, an ex-soldier and small business operator, represents fiscal responsibility and skepticism toward Wolfie's utopian fantasies, highlighting how stable, two-parent units foster accountability and modest prosperity amid 1970s economic pressures.[35] This mirrors empirical findings from UK cohort studies showing that intact families correlate with superior economic outcomes, including higher household resources and reduced reliance on welfare, as non-intact structures often exacerbate resource shortages through divided incomes and caregiving burdens.[36][37] The series eschews romanticized narratives of proletarian struggle, presenting anti-capitalist rhetoric as a distraction from self-inflicted economic woes, such as mounting debts from pub brawls or failed schemes rather than wage suppression. Creator John Sullivan, drawing from his South London working-class roots, crafted these portrayals to reflect authentic idleness-driven poverty traps, where ideological fervor supplants work ethic, aligning with historical recognitions of "idleness" as a barrier to self-sufficiency akin to Beveridge's post-war "five giants" facing reconstruction.[10][38] Married or stable partnerships, as evidenced in Shirley's aspirations for domestic security, underscore long-term financial gains from commitment, with data indicating coupled households accrue wealth advantages through shared labor and risk mitigation, countering the volatility of solo or unstable arrangements.[39]Plot Summaries

Series 1 (1977)

The first series of Citizen Smith, comprising seven episodes broadcast weekly on BBC One from 3 November to 15 December 1977, introduced the core premise of the Tooting Popular Front (TPF), a ragtag group of six aspiring revolutionaries led by the bombastic but hapless Walter "Wolfie" Smith.[40] Wolfie, portrayed by Robert Lindsay, styles himself as a modern Che Guevara, routinely bellowing "Power to the people!" while plotting the overthrow of capitalism from his south London base in Tooting, yet his leadership is marked by chronic disorganization and a membership more interested in personal distractions than ideology.[41] The series establishes the satirical template through Wolfie's grandiose schemes—such as organizing ill-fated rallies and a bungled hostage-taking of a local Tory MP—that repeatedly collapse under the weight of logistical failures, internal squabbles, and encounters with prosaic authority figures like police and landlords.[42] Romantic and domestic tensions form a parallel arc, underscoring the disconnect between Wolfie's revolutionary fervor and everyday banalities; his live-in girlfriend Shirley grapples with his unemployment and immaturity, while her parents, the conservative Mr. and Mrs. Johnson, provide comic foils through their exasperation with the TPF's intrusions into their household.[43] Episodes highlight early dynamics, including sidekick Ken's infatuations and Speed's petty criminal tangents, which dilute the group's focus and amplify the humor derived from micro-scale "revolutions" confined to pub meetings and borrowed vans rather than mass uprisings.[40] This inaugural run sets the tone of optimistic delusion clashing with unyielding reality, portraying left-wing activism not as a viable force but as a source of farcical self-sabotage amid 1970s Britain's economic stagnation and social conservatism.[4] The series' foundational humor revolves around the TPF's minuscule scale and Wolfie's unchecked ego, with schemes like protesting joblessness or seizing symbolic targets fizzling into absurdity, as when a planned political statement devolves into chaos due to miscommunications and lack of support.[42] These elements build viewer engagement by contrasting Wolfie's heroic self-image—complete with leather jacket and motorcycle—against his dependence on parental tolerance and failed heists, laying groundwork for recurring motifs of ideological posturing undermined by human frailty.[1]Series 2 (1978)

Series 2 advanced the narrative by intensifying Wolfie Smith's bumbling revolutionary pursuits against the backdrop of mounting economic turmoil in late 1978 Britain, where factory redundancies and labor disputes foreshadowed the widespread strikes of the Winter of Discontent.[44] The six aired episodes, broadcast on BBC One from 1 December to 12 January 1979, portrayed the Tooting Popular Front's schemes as increasingly detached from practical realities, with Wolfie's ideological fervor clashing against personal and familial obligations.[45] A seventh episode was postponed due to BBC industrial action on 22 December 1978, mirroring the era's union-led disruptions that halted broadcasting and highlighted the irony of scripted activism amid genuine unrest.[46] Character relationships deepened, particularly Wolfie's fraught dynamic with Shirley's father, whose job loss in "Rebel Without a Pause" prompted a futile protest outside the factory gates, underscoring Wolfie's preference for grand gestures over effective support.[44] In "Speed's Return," the reappearance of imprisoned comrade Speed exposed internal fractures within the Front, as petty jealousies and failed solidarity efforts revealed persistent blind spots in their collectivist rhetoric.[47] Episodes like "The Tooting Connection" escalated the farce through entanglement with local criminal Fenning over stolen stereos, blending domestic squabbles with half-hearted criminality that mocked the group's pretensions to guerrilla status.[48] The series shifted toward humor rooted in everyday failures, such as Wolfie's brief employment as a "Working Class Hero" at the Labour Exchange protest, which quickly unraveled due to his incompetence, critiquing the opportunity costs of perpetual activism—lost wages, strained relationships, and ignored personal advancement.[49] Ventures into absurdity, including dreams of rock stardom in "Rock Bottom" and family holiday mishaps in "Spanish Fly," further illustrated ideological rigidity, as Wolfie invoked Marxist slogans to justify inaction on pressing issues like unemployment and financial strain affecting his circle.[50] These plots amplified the satire on left-wing posturing, portraying schemes that consistently collapsed under their own weight, detached from the real-world hardships of inflation and job insecurity gripping Tooting residents.[3]Series 3 (1979)

Series 3 aired on BBC One from 20 September to 6 December 1979, comprising seven half-hour episodes that advanced the characters' entanglement in personal crises alongside their habitual political posturing.[51] The season depicted Wolfie Smith and the Tooting Popular Front grappling with immediate domestic upheavals, such as housing instability and romantic strains, which repeatedly undermined their grandiose schemes for societal overthrow. These narratives illustrated the protagonists' persistent inability to translate ideological fervor into effective action, with comedic emphasis on logistical blunders and interpersonal conflicts.[52] Broadcast in the months following the 3 May 1979 general election, in which Margaret Thatcher's Conservative Party won 339 seats to Labour's 269, the episodes portrayed the radicals' activities as increasingly anachronistic amid a national pivot toward economic liberalization and reduced union influence. Wolfie's leadership of the TPF involved ill-conceived ventures like commandeering a military tank after a drunken escapade or attempting council lobbying that devolved into trapping themselves in a lift, outcomes that empirically reinforced their operational incompetence irrespective of external political winds.[53] Such plots highlighted causal disconnects, where abstract calls for "power to the people" yielded no tangible progress, mirroring the marginalization of fringe leftist groups in late-1970s Britain.[35] Personal responsibilities intensified dramatic tension, particularly in storylines exposing rifts between revolutionary rhetoric and relational duties; for instance, Shirley's temporary relocation to Italy precipitated Wolfie's eviction and confrontation with his aimless lifestyle, forcing fleeting reflections on self-sufficiency over subversion.[51] Episodes like "The Big Job" further dramatized this gap, as Wolfie's pivot to petty crime for funding the cause predictably collapsed, prioritizing short-term expediency over principled strategy and amplifying the humor in unaltered patterns of defeat.[52] By season's close in "The Glorious Day," the group's hijacking of an abandoned tank symbolized aspirational delusion without execution, underscoring how individual failings perpetuated collective stasis.[53]Series 4 (1980)

Series 4 commences with the Tooting Popular Front members, including Wolfie Smith, serving time in an open prison following the botched coup attempt from the previous series. In the premiere episode, "Bigger Than Guy Fawkes," aired on 23 May 1980, Wolfie briefly gains notoriety when a show business agent promotes him as a marketable "singing revolutionary," securing temporary luxury accommodations and media deals upon parole; however, his impulsive deviations from scripted interviews lead to public backlash and the collapse of the opportunity.[54] [55] Speed's ill-conceived escape tunnel efforts further underscore the group's habitual disarray, while early release hinges on good behavior, highlighting their shift toward reluctant conformity.[54] Subsequent episodes, beginning with "Changes" on 30 May 1980, portray Wolfie and Ken's return to a transformed Tooting, where local developments like new pub ownership by Ronnie Sykes challenge their stagnant worldview; Wolfie vows to "restore" the status quo, clashing with altered social dynamics and forcing minor adaptations from the ideologues.[56] [57] This theme of resignation intensifies in "The Final Try" on 6 June 1980, as Wolfie targets a multi-racial South African rugby team's UK tour—viewed through his anti-apartheid lens as a fascist symbol—attempting to derail their bus and later kidnapping team dogs, only for the scheme to unravel amid logistical failures and unintended consequences that halt the match independently.[58] [59] [60] Later installments emphasize personal entanglements over grand revolution. In "The Letter of the Law" on 13 June 1980, Wolfie serves on a jury trying local figure Ronnie Lynch for bribery, grappling with evidence and Lynch's self-defense claims, which expose Wolfie's naive absolutism against legal pragmatism.[55] [61] "Prisoners" on 20 June 1980 involves Speed and an associate holding Wolfie's parents hostage to recover hidden loot, sparking a chaotic retrieval that devolves into disputes over its capitalist uses, further eroding group unity.[61] "Casablanca Was Never Like This" sees the TPF employing a private detective to exonerate Speed in a jewel heist, resolved inadvertently by a dog's intervention, satirizing their reliance on external fixes.[55] The season concludes with "Sweet Sorrow" on 4 July 1980, where Wolfie steals motorway blueprints to thwart development threatening Tooting, confronting Ronnie in a confrontation that ends with Wolfie fleeing after an compromising liaison with Mandy, symbolizing his slide into self-sabotaging compromises.[61] [55] Across these six core episodes—supplemented by a standalone Christmas special on 31 December 1980—the narrative arcs toward Wolfie's tragicomic tenacity amid repeated defeats, with the TPF's schemes yielding personal reckonings rather than systemic upheaval, reflecting a broader dilution of their Marxist zeal.[61][62]Reception

Contemporary Reviews

Upon its premiere in November 1977, Citizen Smith garnered acclaim for Robert Lindsay's energetic and charismatic depiction of Wolfie Smith, the self-proclaimed leader of the Tooting Popular Front, whose revolutionary zeal clashed comically with everyday banalities. Critics highlighted the performance's ability to blend earnest idealism with inherent ridiculousness, making the character both endearing and absurd. John Sullivan's scripting was similarly commended for its sharp observational humor, capturing the era's widespread strikes and militant posturing through exaggerated yet grounded ineptitude.[63] The series' satirical edge on left-wing activism elicited divided responses, with some reviewers decrying it as a reductive caricature that undermined genuine political commitment by focusing on personal failings over systemic critiques. Others, however, valued its unflinching portrayal of ideological fervor devolving into farce, arguing it truthfully mirrored the disconnect between rhetoric and reality in 1970s radical groups. This tension reflected broader debates in British media, where conservative-leaning outlets embraced the show's realism, while progressive voices saw bias in its mockery of socialist aspirations.[64]Viewership and Ratings

Citizen Smith garnered solid audience figures in its initial seasons on BBC One, ranking among the top 10 most-viewed programs in 1979.[65] This placed it alongside other popular BBC sitcoms like Are You Being Served? and To the Manor Born, reflecting commercial viability in a competitive landscape dominated by variety shows and dramas drawing 15-20 million viewers at peak.[65] By the fourth series in 1980, viewership declined, coinciding with disruptions from the 1979 BBC technicians' strike, which halted productions and delayed transmissions from August to October, fragmenting audience habits. The shift followed the May 1979 general election, where parodies of fervent left-wing activism may have encountered audience fatigue amid changing political realities, though exact causal links remain inferential from scheduling impacts and era-specific trends. In comparison to contemporaries like Fawlty Towers, which built escalating ratings—starting modestly on BBC Two in 1975 before surging to strong BBC One performance in 1979—Citizen Smith maintained niche appeal through its pointed critique of ideological excesses, without matching the universal farce-driven draw of broader situational humor. This underscored its targeted resonance with viewers attuned to 1970s socio-political satire, sustaining four series despite not dominating charts.[65]Criticisms and Controversies

Citizen Smith encountered minimal criticisms during its original broadcast, with no documented major controversies arising from its satirical depiction of inept Marxist revolutionaries in the Tooting Popular Front. The series' four-season run from April 12, 1977, to December 31, 1980, without public outcry or censorship suggests its comedic exaggeration of fringe left-wing group dynamics—mirroring real 1970s splinter factions prone to infighting and inaction—was viewed as benign entertainment rather than offensive stereotyping.[1] Some retrospective commentary from left-leaning observers has likened the protagonist Wolfie Smith to ineffective modern socialists, using the term "Citizen Smith" as shorthand for performative radicalism, as noted by journalist Grace Dent in reference to Jeremy Corbyn's supporters in 2017. This implies tacit acceptance of the show's empirical observation of human folly in political activism, countering potential claims of "punching down" by highlighting universal pretension over class-based malice; the satire equally lampooned authority figures like police and landlords, aligning with causal patterns of ideological groups' frequent dysfunction regardless of orientation.[10] Minor critiques focused on narrative quality rather than politics, such as the addition of overly simplistic characters in later series diluting initial sharp humor, but these did not impact its cultural endurance.[29]Legacy and Adaptations

Cultural Impact

Citizen Smith marked the breakthrough for writer John Sullivan, whose debut sitcom honed his style of blending working-class vernacular with social observation, directly influencing his subsequent creation of Only Fools and Horses, a series that achieved peak viewership of over 24 million for its 1996 Christmas special and defined 1980s-1990s British comedy.[66] The show's experimental edge in satirizing radical politics has been likened to precursors of more anarchic works like The Young Ones, emphasizing character-driven absurdity over plot.[66] For lead actor Robert Lindsay, the role of Wolfie Smith brought rapid fame, with episodes drawing audiences that made public recognition overwhelming and the catchphrase "Power to the people!" culturally resonant, as evidenced by crowds chanting it at events like a 1979 Police concert.[20] The series' core satire targeted the inefficacy of 1970s leftist activism, portraying Wolfie's Tooting Popular Front as mired in inertia and delusion despite revolutionary rhetoric—a depiction that highlighted the causal gap between ideological fervor and practical outcomes, such as failed plots derailed by personal failings or apathy.[29] This realism in illustrating utopian aspirations thwarted by human nature prefigured broader critiques of persistent radical movements that prioritize slogans over structural change, a theme undiluted by the era's industrial unrest where strikes and economic woes empirically failed to yield systemic overthrow.[10] In political discourse, Citizen Smith retains relevance for encapsulating the folly of idealistic Marxism, with commentators invoking Wolfie as an archetype for figures like Jeremy Corbyn, whose 2010s leadership evoked similar beret-wearing zeal amid Labour's internal divisions and electoral setbacks—evidenced by the party's 2019 defeat despite activist mobilization.[10] The show's legacy thus lies in educating audiences on historical revolutionaries like Che Guevara while underscoring activism's frequent descent into factionalism, as noted in reflections on left-wing self-critique: "The more left you become, the more you loathe other lefties."[10] Mainstream sources, often aligned with progressive viewpoints, acknowledge this without fully grappling with the empirical persistence of such dynamics across decades.[10]Novelization

Citizen Smith, a novelization of the first series of the BBC television sitcom, was authored by Christopher Kenworthy and published in 1978 by Universal Books in London as a 192-page paperback priced at 75 pence.[67][68] The book adapts episodes featuring the protagonist Wolfie Smith, an unemployed self-proclaimed Marxist revolutionary leading the fictional Tooting Popular Front, who attempts to overthrow capitalism through inept schemes while relying on friends and family for support.[68] Subplots involve Wolfie's girlfriend Shirley (Shirl) and comrade Ken, highlighting everyday absurdities in South London working-class life amid his grandiose ideological posturing.[68] Kenworthy's adaptation preserves the original series' satirical edge, depicting Wolfie's revolutionary zeal as comically undermined by personal laziness, financial dependence, and inconsistent commitment to Marxist principles, such as "redistributing" wealth by freeloading rather than productive action.[68] Unlike the television format, the novel incorporates narrative prose to delve into characters' thoughts and motivations, allowing for expanded internal reflections on Wolfie's hypocrisies—such as preaching equality while exploiting others—beyond the visual and dialogue-driven humor reliant on Robert Lindsay's performance.[68] This textual approach emphasizes the causal disconnect between Wolfie's rhetoric and his actions, underscoring the series' critique of performative radicalism without altering core plot events from the 1977 episodes.[68] The novel saw a modest print run typical of 1970s BBC tie-in publications, contributing to its status as a collector's item among fans of British sitcom memorabilia, with surviving copies often appearing in vintage markets showing signs of age like spine fading.[69] Reception was generally positive among contemporary readers for capturing the show's spirit, evidenced by an average rating of 3.8 out of 5 from user reviews on literature platforms, though some critiques noted the prose as clichéd and less engaging without the actors' delivery.[70] No significant controversies arose regarding the adaptation, which stayed faithful to John Sullivan's scripts without introducing substantive deviations or ideological reinterpretations.[68]Mooted Revivals and Modern Relevance

In 2015, discussions emerged within the BBC about potentially reviving Citizen Smith, with actor Robert Lindsay advocating for a return of the series amid perceived parallels between Wolfie Smith's ineffective revolutionary rhetoric and the ideological fervor surrounding Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn's leadership bid. Lindsay, in interviews, suggested the character's "power to the people" slogan resonated with contemporary left-wing activism, proposing an aged-up Wolfie navigating modern politics. However, these plans were swiftly denied by the estate of creator John Sullivan, who controlled the rights and emphasized that no formal proposals had been received or approved. The estate's rejection highlighted concerns over fidelity to Sullivan's original vision, which relied on the specific socio-economic absurdities of 1970s Britain, such as high inflation and union militancy, rendering broad updates potentially tonally inconsistent. Creative differences ultimately stalled any progress, with Lindsay's enthusiasm clashing against the estate's insistence on avoiding unauthorized adaptations that could dilute the satire's historical bite. Reports from the period noted industry interest but no scripted commitments, underscoring the challenges of resurrecting period-specific comedies without the original writer's input. No subsequent revival efforts or BBC announcements have surfaced in the decade since, including through 2025, reflecting a broader reluctance to revisit Sullivan's works beyond established formats like Only Fools and Horses. The series' enduring relevance lies in its portrayal of aspirational radicalism undermined by personal incompetence and external realities, a dynamic invoked in 2015 analyses linking Wolfie's delusions to Corbyn-era promises of systemic overhaul amid economic constraints. Proponents of revival argued for adapting the premise to critique modern populist movements—encompassing both left-wing collectivism and anti-establishment fervor—where ideological declarations often outpace feasible governance. Critics, including Sullivan's estate, countered that such updates risk blunting the original's precision, as the 1970s context of state overreach and failed socialism provided irreplaceable causal grounding for the humor, distinct from today's decentralized populism or market-driven disruptions. This tension illustrates broader debates on comedic timelessness, where empirical fidelity to era-specific causal factors preserves satirical efficacy over generalized applicability.Episode List

Series Overviews and Key Episodes

Citizen Smith aired a pilot episode on 12 April 1977, followed by four series totaling 30 episodes on BBC One from 3 November 1977 to 31 December 1980.[71] The pilot introduced Wolfie Smith, an aspiring revolutionary leading the fictional Tooting Popular Front (TPF), and his housemates in Tooting, South London.[3] Series overviews highlight the recurring theme of Wolfie's grandiose political schemes clashing with mundane personal and domestic realities, often involving his girlfriend Shirley, her parents, and TPF comrades Ken and Speed.[2] Series 1 (1977)Aired from 3 November to 22 December 1977 across eight episodes, this series established the core ensemble and Wolfie's ineffective activism amid everyday frustrations like unemployment and family tensions.[71]

- "Citizen Smith" (pilot, 12 April 1977): Wolfie rallies his group for initial revolutionary efforts.[8]

- "Crocodile Tears" (3 November 1977): Wolfie suspects betrayal within the TPF.[8]

- "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" (10 November 1977): Family dinner leads to ideological clashes.[8]

- "Abide with Me" (17 November 1977): Wolfie navigates religious and political contradictions.[8]

- "The Weekend" (24 November 1977): A group outing exposes personal dynamics.[8]

- "The Hostage" (1 December 1977): Wolfie plans a bold political statement.[8]

- "The Laundry" (8 December 1977): Domestic chores intersect with activism.[8]

- "A Story for Christmas" (22 December 1977): Holiday festivities test revolutionary resolve.[71]

Six episodes aired from 1 December 1978 to 16 August 1979, expanding on TPF misadventures with returning characters and escalating absurd plots.[71]

- "Speed's Return" (1 December 1978): A comrade's comeback stirs group activities.[5]

- "Rebel Without a Pause" (8 December 1978): Wolfie pushes anti-establishment actions.[5]

- "The Tooting Connection" (15 December 1978): Local ties complicate plans.[5]

- "A Fishy Business" (12 January 1979): Business ventures go awry.[8]

- "The Power and the Glory" (unknown exact date in series): Ideological fervor meets reality.[71]

- "Spanish Fly" (16 August 1979): Travel mishaps abroad.[71]

Seven episodes from 20 September to 1 November 1979, intensifying satirical elements on politics and society.[71] Key episode "The Glorious Day" (1 November 1979) exemplifies peak satire through the TPF's improbable encounter with military assets after a night out, underscoring delusions of grandeur.[53]

- "Don't Look Down" (20 September 1979): Heights and fears challenge the group.[72]

- "The Party's Over" (27 September 1979): Social events derail focus.[72]

- "We Shall Not Be Moved" (4 October 1979): Protest stance is tested.[8]

- "Tofkin's Revenge" (11 October 1979): Past grievances resurface.[8]

- "The Big Job" (18 October 1979): Ambitious undertaking unfolds.[8]

- "Only Fools and Horses..." (25 October 1979): Crossovers hint at broader folly.[72]

- "The Glorious Day" (1 November 1979): Military escapade highlights revolutionary fantasies.[53]

Seven main episodes from 23 May to 4 July 1980, plus Christmas special "Buon Natale" (31 December 1980), concluding with reflective tones on persistence amid failure.[71]

- "Bigger Than Guy Fawkes" (23 May 1980): Explosive plot ambitions.[8]

- "King of the Mountain" (30 May 1980): Leadership rivalries emerge.[8]

- "A Question of Principle" (6 June 1980): Ethical dilemmas arise.[8]

- "In the Bread Box" (13 June 1980): Confinement sparks ideas.[8]

- "Prisoners" (20 June 1980): Captivity themes explored.[8]

- "The Goods" (27 June 1980): Acquisition schemes.[8]

- "Sweet Sorrow" (4 July 1980): Farewells and reflections.

- "Buon Natale" (31 December 1980): Festive wrap-up with Italian flair.[71]