Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Community development block

View on Wikipedia

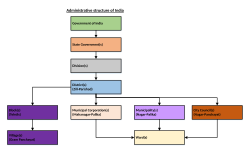

In India, a community development block (CD block) or simply Block is a sub-division of District, administratively earmarked for planning and development.[1] In tribal areas, similar sub-divisions are called tribal development blocks (TD blocks).[2] The area is administered by a Block Development Officer (BDO), supported by several technical specialists and village-level workers.[3] A community development block covers several gram panchayats, the local administrative units at the village level. A block is a rural subdivision and typically smaller than a tehsil. A tehsil is purely for revenue administration, whereas a block is for rural development purposes. In most states, a block is coterminous with the panchayat samiti area.[4][5][6]

Nomenclature

[edit]The nomenclature varies from state to state, such as common terms like "block" and others including community development block, panchayat union block, panchayat block, panchayat samiti block, development block, etc. All denote a CD Block, which is a subdivision of a district, exclusively for rural development.[7][6][4]

History

[edit]The concept of the community development block was first suggested by Grow More Food (GMF) Enquiry Committee in 1952 to address the challenge of multiple rural development agencies working without a sense of common objectives.[8] Based on the committee's recommendations, the community development programme was launched on a pilot basis in 1952 to provide for a substantial increase in the country's agricultural programme, and for improvements in systems of communication, in rural health and hygiene, and in rural education and also to initiate and direct a process of integrated culture change aimed at transforming the social and economic life of villagers.[9] The community development programme was rapidly implemented. In 1956, by the end of the first five-year plan period, there were 248 blocks, covering around a fifth of the population in the country. By the end the second five-year plan period, there were 3,000 blocks covering 70 per cent of the rural population. By 1964, the entire country was covered.[10]

Block Development Officer

[edit]A Block Development Officer (BDO) is an administrative officer in India responsible for the overall development of a Community Development Block (CD Block), a sub-division of a district. They are appointed by the state government and report to the Chief Development Officer (CDO) or District Development Commissioner or the similar position.

They typically fall under the purview of the Rural Development Department or Department of Panchayats of the respective state government. The BDO is responsible for overall supervision of all the antipoverty schemes and execution of the Developmental works.

The BDO functions as the Secretary of the Panchayat Samiti/Block Panchayat and exercises supervision and control over the extension officers and other employees of the Panchayat Samiti and the staff borne on transferred schemes.

Blocks statewise

[edit]| State | CD Block | Number of CD Blocks |

|---|---|---|

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | CD Block | 9 |

| Andhra Pradesh | Mandal | 668 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | Block | 129 |

| Assam | Block | 239 |

| Bihar | Block | 534 |

| Chandigarh | Block | 3 |

| Chhattisgarh | CD Block | 146 |

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu | CD Block | 3 |

| Delhi | CD Block | 342 |

| Goa | CD Block | 12 |

| Gujarat | CD Block | 250 |

| Haryana | Block | 143 |

| Himachal Pradesh | CD Block | 88 |

| Jammu and Kashmir | CD Block | 287 |

| Jharkhand | Block | 264 |

| Karnataka | CD Block | 235 |

| Kerala | Block | 152 |

| Ladakh | CD Block | 31 |

| Lakshadweep | CD Block | 10 |

| Madhya Pradesh | CD Block | 313 |

| Maharashtra | CD Block | 352 |

| Manipur | CD Block | 70 |

| Meghalaya | CD Block | 54 |

| Mizoram | CD Block | 28 |

| Nagaland | CD Block | 74 |

| Odisha | CD Block | 314 |

| Puducherry | CD Block | 6 |

| Punjab | CD Block | 153 |

| Rajasthan | CD Block | 353 |

| Sikkim | CD Block | 33 |

| Tamil Nadu | Taluk | 388 |

| Telangana | Mandal | 594 |

| Tripura | CD Block | 58 |

| Uttar Pradesh | CD Block | 826 |

| Uttarakhand | CD Block | 95 |

| West Bengal | CD Block | 345 |

References

[edit]- ^ Maheshwari, Shriram. "Rural Development and Bureaucracy in India". The Indian Journal of Public Administration. XXX (3): 1093–1100.

- ^ Vidyarthi, Lalita Prasad (1981). Tribal Development and Its Administration. Concept Publishing Company.

- ^ Sharma, Shailendra D. (1999). Development and Democracy in India. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc. ISBN 9781555878108.

- ^ a b "Development Blocks | District Barabanki, Government of Uttar Pradesh | India". Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ CD Blocks of Assam. "Administrative setup".

- ^ a b "GUIDELINES FOR THE WORKING ARRANGEMENTS OF THE NEWLY CREATED ADDITIONAL BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICERS IN THE PANCHAYAT UNION ADMINISTRATIVE SET-UP" (PDF). Rural Development Department, Government of Tami Nadu.

- ^ "Block development offices; Kerala, Commissionerate of Rural Development".

- ^ Report of The Grow More Food Enquiry Committee. Government of India Ministry of Food and Agriculture. 1952.

- ^ "First Five Year Plan". Planning Commission. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "The Failure of the Community Development Programme in India". Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ https://pdi.gov.in/demo/MDV/Public/State-wise-Summary.aspx [bare URL]