Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Concealed carry

View on Wikipedia

Concealed carry, or carrying a concealed weapon (CCW), is the practice of carrying a weapon (usually a sidearm such as a handgun), either in proximity to or on one's person in public places in a manner that hides or conceals the weapon's presence from surrounding observers. In the United States, the opposite of concealed carry is called open carry.

While most law enforcement officers carry their handguns in a visible holster, some officers such as plainclothes detectives or undercover agents carry weapons in concealed holsters. In some countries and jurisdictions, civilians are legally required to obtain a concealed carry permit in order to possess and carry a firearm. In others, a CCW permit is only required if the firearm is not visible to the eye, such as carrying the weapon in one's purse, bag, trunk, etc.

By country

[edit]United States

[edit]

Concealed carry is legal in most jurisdictions of the United States. A handful of states and jurisdictions severely restrict or ban it, but all jurisdictions make provision for legal concealed carry via a permit or license, or via constitutional carry. Illinois was the last state to pass a law allowing for concealed carry, with license applications available on January 5, 2014.[2] Most states that require a permit have "shall-issue" statutes, and if a person meets the requirements to obtain a permit, the issuing authority (typically, a state law enforcement office such as the state police) must issue one, with no discretionary power given. Prior to June 2022, a few states enforced "may-issue" statutes, which gave authorities discretionary power in issuing permits to otherwise qualified applicants. However, these laws were found to be unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen. Furthermore, in most states obtaining the permit is required to bring a weapon into public, (e.g. shopping center). If the gun remains in one's vehicle but is not on said person's property, a permit is required in places like New Jersey.

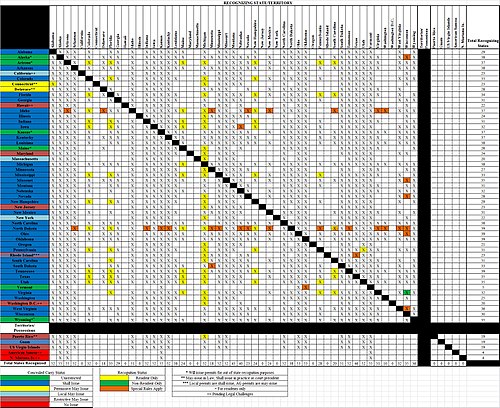

Further complicating the status of concealed carry is recognition of state permits under the laws of other states. The Full Faith and Credit Clause of the US Constitution pertains to judgments and other legal pronouncements such as marriage and divorce rather than licenses and permits that authorize individuals to prospectively engage in activities. There are several popular combinations of resident and nonresident permits that allow carry in more states than the original issuing state; for example, a Utah nonresident permit is recognized for carry in 30 states. Some states, however, do not recognize permits issued by other states to nonresidents of the issuing state: Colorado, Florida, Maine, Michigan, New Hampshire, North Dakota and South Carolina. Some other states do not recognize any permit from another state: California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois (recognizes permits while in vehicle), Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island (recognizes permits while in vehicle) and the District of Columbia.

United Kingdom

[edit]Concealed or open carry of any weapon is generally prohibited in Great Britain (i.e. England, Wales, and Scotland), the Prevention of Crime Act 1953 prohibiting this in a public place.[3][4][5] Permission exists only with lawful authority or reasonable excuse. As per Section 1(4) Prevention of Crime Act 1953, the definition of an offensive weapon is: "offensive weapon" means any article made or adapted for use for causing injury to the person, or intended by the person having it with him for such use by him or by some other person.[6] Self defence is no longer considered a legitimate reason for the granting of a Firearms Certificate (FAC) in Great Britain.

Unlike Great Britain, Northern Ireland still allows the carry of concealed handguns for the purpose of self defence. An FAC for a personal protection weapon will only be authorised where the Police Service of Northern Ireland deems there is a "verifiable specific risk" to the life of an individual, and that the possession of a firearm is a reasonable, proportionate and necessary measure to protect their life.[7] Permits for personal protection also allow the holder to carry their firearms concealed.[8] In reality – aside from off-duty constables – the only individuals who will be granted a permit to carry will be those who are government officials or retirees, such as prison officers, military personnel, or politicians still considered to be at risk from paramilitary attack.

Canada

[edit]The practice of CCW is generally prohibited in Canada. Section 90 of the Criminal Code prohibits carrying a concealed weapon unless authorized for a lawful occupational purpose[9] under the Firearms Act.[10] Section 20 of the Firearms Act allows issuance of an Authorization to Carry (ATC) in limited circumstances. Concealment of the firearm is permitted only if it is specifically stipulated in the conditions of the ATC, as section 58(1) of the Firearms Act allows a CFO to attach conditions to an ATC.

Provincial chief firearm officers (CFOs) may only issue an authorization in accordance with the regulations. Specifically, SOR 98-207 section 2 requires, for an ATC for protection of life, for an individual to be in imminent danger and for police protection to be insufficient. As such, if the relevant police agency determines its protection is sufficient, the CFO would have difficulty in issuing the ATC over police objections.

For issuance of an ATC under 98-207(3) for lawful occupations, provision is made for armored car personnel under subsection a), for wildlife protection (while working) and trapping under subsections b) and c). Unless hunting or other activity is occupational, it would not be possible to issue an ATC under the section.[9] As noted, a CFO can exercise some discretion but must follow the law in considering applications for an ATC.[11]

Brazil

[edit]Concealed carry in Brazil is generally illegal, with special carry permits granted to police officers allowing them to carry firearms off duty, and in other rare cases.[12] In May 2019, President Jair Bolsonaro signed a decree allowing several people to have license to carry a weapon based on the intrinsic risk of the profession, including lawyers, reporters and politicians.[13]

Czech Republic

[edit]A gun in the Czech Republic is available to anybody subject to acquiring a shall-issue firearms license. Gun licenses may be obtained in a way similar to driving licenses – by passing a gun proficiency exam, medical examination and having a clean criminal record. Unlike in most other European countries, the Czech gun legislation also permits a citizen to carry a concealed weapon for self-defense – 246,715 out of some 303,936 legal gun owners have E category licenses which permit them to carry concealed firearms. The vast majority of Czech gun owners possess their firearms for protection, with hunting and sport shooting being less common.

Hunters who hold C category licenses may carry their hunting firearms openly on the way to and from hunting grounds.

Unlike state policemen, members of the municipal police are regarded as civilians and need to obtain D category licenses in order to be armed. Municipal policemen while on duty carry their municipality-issued firearms openly. D category license holders who work in private security services can carry their firearms only in a concealed manner.

All firearms licenses are shall-issue.

| License category | Age | Carrying |

|---|---|---|

| A - Firearm collection | 21 | No carry |

| B - Sport shooting | 18 15 for members of a shooting club |

Transport only (concealed, in a manner excluding immediate use) |

| C - Hunting | 18 16 for pupils at schools with hunting curriculum |

Transport only (open/concealed, in a manner excluding immediate use) |

| D - Exercise of profession | 21 18 for pupils at schools conducting education on firearms or ammunition manufacturing |

Concealed carry (up to 2 guns ready for immediate use) Open carry for members of municipal police, Czech National Bank's security while on duty |

| E - Self-defense | 21 | Concealed carry (up to 2 guns ready for immediate use) |

Mexico

[edit]In Mexico, the issuance of a private individual firearms license, despite being guaranteed as a right in Article 10 of the 1917 Constitution, is neither common nor easy to obtain. Article 10 of the Constitution quotes:

The inhabitants of the United Mexican States have the right to possess arms in their homes, for their security and legitimate defense, with the exception of federal law and those reserved for the exclusive use of the Army, Navy, Air Force and National Guard. Federal law shall determine the cases, conditions, requirements and places in which inhabitants may be authorized to carry weapons.[14]

Even when a carrying permit is granted, it is usually limited to weapons permitted for civilians (also called "non-exclusive military use"). The carrying of arms in Mexico is limited to those detailed in Articles 8 and 9 of the Federal Law on Firearms and Explosives.2 which states

Weapons with the following characteristics may be possessed or carried, under the terms and with the limitations established by this Law:

I. I. Semi-automatic pistols of caliber no greater than .380" (9 mm), with the exception of .38" Super and .38" Comando calibers, and also in 9 mm calibers, Mauser, Luger, Parabellum and Comando, as well as similar models of the same caliber of the exempted ones, of other brands.

II. Revolvers in calibers not superior to .38" Special, being excepted the caliber .357" Magnum.

Ejidatarios, comuneros and rural workers, outside urban areas, may possess and carry with the only demonstration, one of the aforementioned weapons, or a .22" caliber rifle, or a shotgun of any caliber, except those with a barrel length of less than 635 mm. (25"), and those with a caliber greater than 12 (.729" or 18.5 mm.).

III. Those mentioned in Article 10 of this Law.

IV. Those that form part of collections of arms, in the terms of Articles 21 and 22.

The issuance of carrying licences in Mexico is similar to the United States "may-issue" model, in which the authorities responsible for issuing such licences (Secretariat of National Defense) reserve the right to issue them at their discretion.

Pakistan

[edit]Pakistan allows any citizen with a firearm licence to carry a concealed handgun, except in educational institutions, hostels or boarding and lodging houses, fairs, gatherings or processions of a political, religious, ceremonial or sectarian character, and on the premises of courts of law or public offices.[15]

Philippines

[edit]Concealed carry in the Philippines requires a Permit To Carry (PTC), which may be issued to licensed firearms owners based on threats to their lives or because of the inherent risk of their profession. The Permit to Carry must be renewed annually.

During gun ban, which is the time of election or as declared by the president, no civilian can carry a gun outside residence even with PTC.

In some private learning institutions, CCW (Carrying Concealed Weapon) is permitted by the management of the institution. Here are the necessary scenarios for a student to request or have a CCW in the institution: When a student is a possible target of life, if the student has experienced sexual harassment, if the student is a VIP student, etc. The student/s may be restricted to 1 non lethal weapon. VIP students and endangered students are immune to the gun ban during all elections. Permit to Carry is signed by the institution for the student.

Poland

[edit]Polish firearm licences for handguns allow concealed carry, regardless of whether they are given for self defence or sporting reasons. Self defence licences are only for those the police consider at heightened risk of attack, and are rare. Sports shooting licences require active participation in competitions every year.

South Africa

[edit]In South Africa, it is legal to carry all licensed firearms and there is no additional permit required to carry firearms open or concealed, as long as it is a licensed firearm that is carried:

- in the case of a handgun, in a holster or similar holder designed, manufactured or adapted for the carrying of a handgun and attached to his or her person or in a rucksack or similar holder.

- in the case of any other firearm, in a holder designed, manufactured or adapted for the carrying of the firearm.

A firearm contemplated in subsection must be completely covered and the person carrying the firearm must be able to exercise effective control over the firearm (carrying firearms in public is allowed if it is done in that manner).[16]

In South Africa, private guns are prohibited in educational institutions, churches, community centres, health facilities, NGOs, taverns, banks, corporate buildings, government buildings and some public spaces, such as sport stadiums.[16]

Slovakia

[edit]Concealed carry in Slovakia is not common and subject to generally permissive may-issue license (depends on jurisdiction; some are essentially shall-issue, while others don't issue without bribe or verifiable proof to being in danger), only 2% of the population hold a licence allowing concealed carry.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Buchanan, Larry; Leatherby, Lauren (June 22, 2022). "Who Stops a 'Bad Guy With a Gun'?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2022.

Data source: Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training Center

- ^ "Illinois State Police | Concealed Carry FAQ". Archived from the original on 2013-07-22. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ^ "Prevention of Crime Act 1953". www.legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ "Selling, buying and carrying knives".

- ^ "Offensive Weapons Charges - Criminal - Services - AFG LAW".

- ^ "Prevention of Crime Act 1953".

- ^ Ryder, Chris (5 January 2003). "Ulster gun owners face weapons licence tests". The Times. London. Retrieved 4 May 2010.[dead link]

- ^ PERSONAL PROTECTION WEAPON POLICY https://www.psni.police.uk/globalassets/advice--information/our-publications/policies-and-service-procedures/policy_directive_09_06.pdf

- ^ a b Program, Government of Canada, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Canadian Firearms (10 October 2019). "Using a Firearm for Wilderness Protection". www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Branch, Legislative Services (27 August 2021). "Consolidated federal laws of canada, Criminal Code". laws-lois.justice.gc.ca.

- ^ Branch, Legislative Services (22 March 2006). "Consolidated federal laws of canada, Authorizations to Carry Restricted Firearms and Certain Handguns Regulations". laws-lois.justice.gc.ca.

- ^ "LEI No 10.826, DE 22 DE DEZEMBRO DE 2003". December 22, 2003. Retrieved 2015-05-09.

- ^ "D9797".

- ^ Pérez Hernández, José Francisco Pedro (2017-03-17). "La Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos y el Ayuntamiento en el Municipio Mexicano". Revista de la Facultad de Derecho de México. 67 (267): 393. doi:10.22201/fder.24488933e.2017.267.58903. ISSN 2448-8933.

- ^ Pakistan.1965.‘Prohibition of Keeping, Carrying, or Displaying Arms.’ Pakistan Arms Ordinance 1965 (W.P. Ord. XX of 1965).Islamabad:Central Government of Pakistan,8 June. (Q2245)

- ^ a b Alpers, Philip. "Guns in South Africa — Firearms, gun law and gun control". www.gunpolicy.org.

- ^ "Concealed Carry in Slovakia". 2014. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

Concealed carry

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Principles

Definition and Distinctions

Concealed carry is the practice of carrying a firearm, typically a handgun, on or about one's person in a manner that hides it from the ordinary view of others.[1] This involves positioning the weapon under clothing or in a pocket, purse, or holster designed to prevent visibility.[11] The primary purpose is to enable lawful self-defense while minimizing detection, distinguishing it from offensive armament.[12] It differs from open carry, in which the firearm remains plainly visible, such as in a holster exposed on the hip or chest.[13] Open carry emphasizes deterrence through visibility, whereas concealed carry prioritizes discretion and surprise in potential defensive scenarios.[14] Concealed carry also contrasts with constitutional carry, also known as permitless carry, where eligible adults face no permit requirement to carry concealed, unlike systems mandating government-issued authorization.[15] Micro-compact 9mm pistols are generally favored for concealed carry, offering a balance of stopping power, manageable recoil, high capacity, and affordable ammunition compared to smaller calibers like .380 or larger ones like .40/.45.[16] Common firearms for concealed carry are compact or subcompact handguns, selected for their size that facilitates hiding without printing—unintended outlines under fabric.[16] Retention holsters, such as inside-the-waistband or appendix styles, secure the weapon close to the body. Appendix carry, typically in the 1-2 o'clock position (with significant overlap including 2 o'clock often categorized under appendix or appendix inside-the-waistband definitions), directs the muzzle toward the body, presenting a primary safety concern of negligent discharge potentially striking the groin or femoral artery—unlike traditional strong-side hip carry (3-4 o'clock positions), where the muzzle points away from vital areas. With quality holsters that fully cover the trigger guard, strict trigger discipline, and proper training, appendix carry is considered comparably safe to hip carry, benefiting from improved firearm retention and accessibility. No substantial safety differences exist specifically between 1 o'clock and 2 o'clock positions. These methods, often paired with loose or layered clothing to maintain concealment, ensure the carrier retains quick access while adhering to the concealed nature of the practice.[17][11]Philosophical and Legal Foundations

The philosophical foundations of concealed carry rest on the natural right to self-preservation, which entails the means necessary for effective defense against threats to life and liberty. John Locke, in his Second Treatise of Government (1689), posits self-preservation as the fundamental law of nature, whereby individuals possess the executive power to punish aggressors and protect their lives, extending to the use of force proportionate to the harm.[18] This right presupposes access to instruments of defense, as mere abstract entitlement without practical capability undermines the principle; Locke argues that in the state of nature, individuals retain authority to employ violence for preservation until civil society delegates it, but core self-defense remains inalienable.[19] English common law traditions reinforced this by recognizing the right to bear arms as an auxiliary to personal security. William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765–1769) describes the subject's right "of having arms for their defence, suitable to their condition and degree," framing it as essential to counter sudden violence where state protection is absent or delayed.[20] St. George Tucker's annotations to Blackstone emphasize that "the right of self defence is the first law of nature," inherently including arms as the primary tool, with limitations only to prevent abuse rather than negate the entitlement.[21] These traditions view bearing arms not as a privilege but as a corollary to the duty of self-reliance, grounded in the causal reality that threats often arise unpredictably, rendering reliance on distant authorities insufficient for immediate survival. Concealed carry aligns with these foundations by enabling discreet readiness, minimizing provocation while preserving the capacity for swift response. Natural law theorists argue that the right to self-defense logically requires possession and carriage of effective arms, as defense demands proximity to the means; without concealment, open carry might escalate non-violent encounters, whereas hidden armament allows rational deterrence through uncertainty—aggressors, modeled as self-interested actors weighing risks without assuming victim altruism or omniscience, face elevated costs from potential armed resistance.[22] This reasoning prioritizes individual agency over collective dependency, acknowledging that human behavior under scarcity favors proactive measures for preservation, independent of state monopolies on force.[23]Historical Development

Pre-20th Century Origins

In ancient and medieval societies characterized by decentralized authority and frequent threats from bandits, rival factions, and lawlessness, individuals commonly concealed small blades for personal defense, as overt armament could provoke conflict or signal vulnerability. Roman legionaries carried the pugio, a short dagger hidden under tunics for close-quarters protection during campaigns or urban unrest.[24] In medieval Europe, civilians relied on compact daggers—such as the rondel or baselard—as everyday backups to larger weapons, often sheathed discreetly in belts or clothing to enable surprise against assailants in travel or markets, where judicial enforcement was sporadic and self-preservation demanded readiness.[25] These practices stemmed from causal necessities: in environments lacking monopolized police power, concealed arms provided asymmetric advantages in defensive encounters, prioritizing survival over visibility. The American colonial era extended this tradition amid frontier perils, where settlers faced indigenous raids, wildlife, and scarce governance, fostering normative self-armed vigilance without modern constabularies. English common law, inherited by the colonies, generally frowned on concealed weapons as duplicitous, yet practical exigencies led to widespread carrying of pistols or knives under cloaks during journeys or settlements; statutes in places like Virginia and Massachusetts even mandated armed presence at churches and militia musters to deter threats collectively.[26] [27] This reflected first-principles reliance on individual agency for security, as colonial records document pioneers equipping concealable firearms for hunts, patrols, and trade routes, underscoring arms as extensions of personal sovereignty in ungoverned expanses. By the 19th century, U.S. urbanization and post-independence violence—exacerbated by dueling cultures and saloon brawls—prompted initial regulations targeting concealed carry, viewed in Southern states as emblematic of stealthy malice rather than honorable defense. Kentucky enacted the first statewide ban in 1813, prohibiting concealed deadly weapons to curb impulsive crimes, followed swiftly by Louisiana that year and Indiana in 1820; by 1850, most Southern legislatures had similar statutes, often rationalized as preserving open, "manly" confrontation over hidden treachery.[28] [29] Nonetheless, enforcement varied, and in Western frontiers like Tombstone, Arizona, where 1880s ordinances restricted public carry to mitigate gunfights, pioneers and lawmen pragmatically concealed sidearms for survival against outlaws, as empirical accounts of stagecoach holdups and ranch disputes attest.[30] These early laws, while curbing urban excesses, tacitly acknowledged concealed carry's roots in self-reliant contexts, where causal threats necessitated discreet preparedness absent reliable state intervention.[27]20th Century Shifts

In the early 20th century, U.S. states increasingly enacted discretionary "may-issue" permitting systems for concealed carry, driven by urban gang violence linked to Prohibition-era organized crime from 1920 to 1933. These laws granted authorities broad latitude to approve or deny permits based on subjective assessments of need, marking a shift from prior open or unregulated practices in many areas. Enforcement varied regionally, with stricter application in cities amid concerns over cheap handguns fueling street crime, while rural jurisdictions often exhibited greater tolerance due to reliance on personal armament for self-defense and frontier traditions.[31] [32] New York's Sullivan Act of 1911 exemplified this restrictive archetype, prohibiting concealed carry of concealable firearms without a police-issued license and imposing rigorous criteria, including demonstrations of "good moral character." Sponsored amid rising pistol-related homicides in immigrant-heavy neighborhoods, the law centralized discretion with urban police officials, influencing subsequent may-issue statutes in states like California and influencing national debates on public safety. By mid-century, similar frameworks proliferated, reflecting progressive-era state centralization that empowered legislatures—often dominated by urban interests—to override local customs and impose uniform controls, ostensibly to curb impulsive violence but effectively limiting armed self-reliance.[33] [34] Post-World War II urbanization exacerbated crime pressures, with surplus military firearms entering civilian hands amid demographic shifts to cities, yet prompting further entrenchment of permit barriers rather than liberalization. The 1960s witnessed a sharp violent crime escalation, as FBI Uniform Crime Reports documented homicide rates rising from 5.1 per 100,000 in 1960 to 9.7 by 1970, straining under-resourced police forces and highlighting gaps in rapid response capabilities. Contemporary debates, including reactions to events like California's 1967 Mulford Act—which restricted open carry in response to armed Black Panther patrols—underscored tensions, with proponents of armed citizens arguing they supplemented policing in high-crime urban voids, though restrictive may-issue dominance persisted amid calls for centralized authority to manage perceived threats.[35] [36]Late 20th and Early 21st Century Expansion

In the 1980s, rising violent crime rates across the United States prompted legislative shifts toward more permissive concealed carry policies, culminating in Florida's enactment of a shall-issue law on October 1, 1987, which required authorities to issue permits to qualified applicants meeting objective criteria such as background checks and firearms training.[12] This reform addressed prior may-issue discretion that often resulted in arbitrary denials, and Florida's model—emphasizing self-defense amid urban crime surges—influenced subsequent adoptions, with states like Georgia, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia following in 1989.[37] By the late 1990s, at least 31 states had implemented shall-issue laws, expanding access for law-abiding citizens and correlating with empirical analyses suggesting deterrence effects on violent crime in adopting jurisdictions.[38] Economist John R. Lott Jr.'s 1997 study, "Crime, Deterrence, and Right-to-Carry Concealed Handguns," analyzed county-level data from 1977 to 1992 and concluded that shall-issue laws reduced violent crimes, including murders by up to 7.65% and rapes by 5.01%, by increasing the risks faced by potential offenders through civilian armament.[7] Lott's findings, later expanded in his 1998 book More Guns, Less Crime, informed policy debates and legislative testimonies, contributing to further adoptions as national violent crime peaked in 1991 before declining sharply in right-to-carry states during the 1990s.[8] While subsequent research has debated the causal magnitude—some panel data studies finding null or modest effects—these analyses underscored self-defense rationales amid real-world crime reductions, bolstering momentum for reform without relying on discretionary permitting barriers.[8] The early 2000s marked a transition toward permitless carry, building on Vermont's longstanding constitutional tradition of allowing concealed handgun carry without government permission since the state's founding.[39] Alaska became the second state to adopt such a policy on June 11, 2003, repealing permit requirements for concealed carry by eligible adults, a move framed as restoring inherent Second Amendment protections for self-defense outside the home.[40] This "constitutional carry" approach accelerated in the 2010s, with states eliminating discretionary hurdles in favor of verifiable eligibility checks at purchase, reflecting growing recognition that permitting regimes imposed undue burdens on lawful exercise of carry rights amid persistent public safety concerns.[41]Legal Frameworks

United States Overview

In the United States, the right to concealed carry of firearms derives from the Second Amendment, which protects an individual's right to keep and bear arms for self-defense, extending to public carry outside the home. The Supreme Court's decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen on June 23, 2022, affirmed that this right encompasses concealed carry of handguns in public spaces, rejecting subjective "proper cause" requirements for permits as inconsistent with historical traditions of firearm regulation from the founding era.[4] The ruling mandates that modern regulations must align with the nation's historical analogue of allowing law-abiding citizens to bear arms for self-protection, without undue restrictions on the manner of carry such as blanket prohibitions on concealment.[42] Federal law establishes no national concealed carry permit system and imposes no general prohibition on concealed carry by eligible individuals, leaving primary regulation to the states. The Gun Control Act of 1968 prohibits certain categories of persons—such as felons, fugitives, unlawful drug users, and those adjudicated mentally defective—from possessing firearms or ammunition, thereby restricting carry eligibility nationwide, but it does not regulate the carrying of concealed weapons by non-prohibited persons in public.[43] Post-Bruen, federal constraints remain limited to prohibitions on carry in specific federal facilities and properties, with no overarching mandate for permits or training at the national level.[44] As of October 2025, approximately 29 states permit concealed carry without a government-issued license for adults aged 21 and older who meet federal eligibility criteria as non-prohibited persons, reflecting a shift toward "constitutional carry" aligned with Bruen's historical standard.[3] These permitless regimes vary in scope, often requiring minimum age compliance and excluding prohibited venues, while the remaining states operate shall-issue permitting systems that approve qualified applicants without discretionary denial. Interstate variances persist absent federal reciprocity legislation, though proposed bills like H.R. 38 seek to standardize recognition of valid state permits across borders.[45] This landscape underscores the Second Amendment's preeminence over state-level discretion in public bearability.State Variations in the US

As of October 2025, 29 states authorize permitless concealed carry for eligible adults, generally those aged 21 or older who are not prohibited from firearm possession under federal or state law, such as felons or individuals with certain domestic violence convictions.[46][47] These states determine eligibility through prohibited categories rather than requiring a separate background check or permit application for everyday carry, though many continue issuing optional permits to facilitate reciprocity with other jurisdictions.[3] Florida exemplifies this shift, enacting permitless carry via House Bill 543, signed by Governor Ron DeSantis and effective July 1, 2023, thereby joining 25 prior adopters and expanding access without mandatory training or fees for basic carry.[48][46] The remaining 21 states operate under shall-issue frameworks, where concealed carry permits must be granted to applicants meeting objective criteria, including background checks, minimum age, residency, and often firearms training mandates.[49][50] For instance, states like Colorado require eight hours of training and live-fire proficiency for permits, with legislative updates in 2025 refining eligibility to align with federal prohibitions while preserving issuance standards.[49] A small number of holdout jurisdictions, including California, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island, retain may-issue systems granting officials discretion over approvals, though these have been subject to federal court challenges post the 2022 Supreme Court ruling in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, which struck down subjective "good cause" requirements as inconsistent with historical Second Amendment traditions.[51][49] Reciprocity agreements among states allow valid out-of-state permits to be honored for concealed carry, with permitless carry in one state sometimes extended recognition in others through legislative or judicial means, though inconsistencies persist.[52] Tools such as the United States Concealed Carry Association's reciprocity maps track these variations, aiding travelers amid roughly 21 million active permits nationwide as of late 2024—down from peaks before permitless expansions reduced demand in adopting states.[52][53] These divergent models reflect ongoing state-level experimentation following Bruen, with permitless frameworks correlating to broader access but prompting debates over uniform standards absent federal reciprocity legislation like H.R. 38.[54][51]International Perspectives

In much of Europe, concealed carry of firearms by civilians is heavily restricted or outright prohibited, reflecting a policy emphasis on public safety through disarmament following high-profile incidents. In the United Kingdom, following the 1996 Dunblane school shooting where 16 children and a teacher were killed, Parliament enacted the Firearms (Amendment) Act 1997, banning private ownership of most handguns and effectively prohibiting concealed carry for self-defense, with exceptions limited to specific professional needs under strict licensing.[55][56] Similar prohibitions prevail across Western Europe, where may-issue permits for concealed carry are rare and typically require demonstrated exceptional need, such as verified threats, rather than general self-defense rights.[57] The Czech Republic stands as a notable exception in Europe, operating a shall-issue system for concealed carry permits grounded in a constitutional right to self-defense, requiring applicants to pass proficiency tests, medical exams, and background checks but granting licenses upon meeting objective criteria without discretionary denial for ordinary citizens.[58] This framework has supported relatively high civilian firearm ownership—around 16 firearms per 100 residents—and concealed carry prevalence, though recent amendments post-2023 mass shooting introduced tighter reporting on unfit owners.[59] In Eastern Europe, trends toward liberalization are evident; Poland issues concealed carry permits on a shall-issue basis for self-defense when applicants provide a justified reason, such as sport shooting or protection needs, leading to a record 46,000 permits issued in 2024 amid rising applications.[60] Slovakia maintains a more discretionary may-issue approach for concealed carry, varying by locality, but permits self-defense possession under regulated conditions.[61] Outside Europe, select high-crime nations have expanded concealed carry allowances to address security gaps. In Brazil, during President Jair Bolsonaro's tenure from 2019 to 2022, over a dozen decrees eased restrictions, enabling shall-issue elements for concealed carry permits, increasing civilian registrations by over 1,400% and correlating with a 34% drop in homicides from pre-2019 peaks, though subsequent administrations reimposed limits like shorter license durations.[62][63] South Africa permits up to four firearms for self-defense under the Firearms Control Act of 2000, including concealed carry with a dedicated license requiring competency certification and motivation of genuine threat, amid persistently high violent crime rates that have spurred reliance on private security over state policing.[64][65] In regions with stringent carry prohibitions and inadequate law enforcement, such expansions reflect causal pressures from crime victimization, where restricted legal options may incentivize unregulated vigilantism, as observed in pre-liberalization Brazil and South African townships.[66]| Country | Concealed Carry Policy | Key Licensing Features |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | Prohibited for civilians | Handgun ban post-1997; no self-defense permits |

| Czech Republic | Shall-issue | Proficiency test, medical exam; constitutional basis |

| Poland | Shall-issue with justified reason | Rising permits; self-defense allowed |

| Brazil (2019-2022) | Expanded shall-issue elements | Permit surge tied to crime reduction |

| South Africa | May-issue for self-defense | Up to 4 firearms; threat motivation required |