Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

A gun is a device that propels a projectile using pressure or explosive force.[1][2] The projectiles are typically solid, but can also be pressurized liquid (e.g. in water guns or cannons), or gas (e.g. light-gas gun). Solid projectiles may be free-flying (as with bullets and artillery shells) or tethered (as with Tasers, spearguns and harpoon guns). A large-caliber gun is also called a cannon. Guns were designed as weapons for military use, and then found use in hunting. Now, there are guns, e.g., toy guns, water guns, paintball guns, etc., for many purposes.

The means of projectile propulsion vary according to designs, but are traditionally effected pneumatically by a high gas pressure contained within a barrel tube (gun barrel), produced either through the rapid exothermic combustion of propellants (as with firearms), or by mechanical compression (as with air guns). The high-pressure gas is introduced behind the projectile, pushing and accelerating it down the length of the tube, imparting sufficient launch velocity to sustain its further travel towards the target once the propelling gas ceases acting upon it after it exits the muzzle. Alternatively, new-concept linear motor weapons may employ an electromagnetic field to achieve acceleration, in which case the barrel may be substituted by guide rails (as in railguns) or wrapped with magnetic coils (as in coilguns).

The first devices identified as guns or proto-guns appeared in China from around AD 1000.[3] By the end of the 13th century, they had become "true guns", metal barrel firearms that fired single projectiles which occluded the barrel.[4][5] Gunpowder and gun technology spread throughout Eurasia during the 14th century.[6][7][8]

Etymology and terminology

[edit]

The origin of the English word gun is considered to derive from the name given to a particular historical weapon. Domina Gunilda was the name given to a remarkably large ballista, a mechanical bolt throwing weapon of enormous size, mounted at Windsor Castle during the 14th century. This name in turn may have derived from the Old Norse woman's proper name Gunnhildr which combines two Norse words referring to battle.[9] "Gunnildr", which means "War-sword", was often shortened to "Gunna".[10]

The earliest recorded use of the term "gonne" was in a Latin document c. 1339. Other names for guns during this era were "schioppi" (Italian translation-"thunderers"), and "donrebusse" (Dutch translation-"thunder gun") which was incorporated into the English language as "blunderbuss".[10] Artillerymen were often referred to as "gonners" and "artillers"[11] "Hand gun" was first used in 1373 in reference to the handle of guns.[12]

Definition

[edit]According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a gun could mean "a piece of ordnance usually with high muzzle velocity and comparatively flat trajectory," " a portable firearm," or "a device that throws a projectile."[13]

Gunpowder and firearm historian Kenneth Chase defines "firearms" and "guns" in his Firearms: A Global History to 1700 as "gunpowder weapons that use the explosive force of the gunpowder to propel a projectile from a tube: cannons, muskets, and pistols are typical examples."[14]

True gun

[edit]According to Tonio Andrade, a historian of gunpowder technology, a "true gun" is defined as a firearm which shoots a bullet that fits the barrel as opposed to one which does not, such as the shrapnel shooting fire lance.[3] As such, the fire lance, which appeared between the 10th and 12th centuries AD, as well as other early metal barrel gunpowder weapons have been described as "proto-guns"[15] Joseph Needham defined a type of firearm known as the "eruptor," which he described as a cross between a fire lance and a gun, as a "proto-gun" for the same reason.[16] He defined a fully developed firearm, a "true gun," as possessing three basic features: a metal barrel, gunpowder with high nitrate content, and a projectile that occluded the barrel.[4] The "true gun" appears to have emerged in late 1200s China, around 300 years after the appearance of the fire lance.[4][5] Although the term "gun" postdates the invention of firearms, historians have applied it to the earliest firearms such as the Heilongjiang hand cannon of 1288[17] or the vase shaped European cannon of 1326.[18]

Classic gun

[edit]Historians consider firearms to have reached the form of a "classic gun" in the 1480s, which persisted until the mid-18th century. This "classic" form displayed longer, lighter, more efficient, and more accurate design compared to its predecessors only 30 years prior. However this "classic" design changed very little for almost 300 years and cannons of the 1480s show little difference and surprising similarity with cannons later in the 1750s. This 300-year period during which the classic gun dominated gives it its moniker.[19] The "classic gun" has also been described as the "modern ordnance synthesis."[20]

History

[edit]Proto-gun

[edit]

Gunpowder was invented in China during the 9th century.[21][22][23] The first firearm was the fire lance, which was invented in China between the 10–12th centuries.[24][25][26] It was depicted in a silk painting dated to the mid-10th century, but textual evidence of its use does not appear until 1132, describing the siege of De'an.[24] It consisted of a bamboo tube of gunpowder tied to a spear or other polearm. By the late 1100s, ingredients such as pieces of shrapnel like porcelain shards or small iron pellets were added to the tube so that they would be blown out with the gunpowder.[27] It was relatively short ranged and had a range of roughly 3 meters by the early 13th century.[28] This fire lance is considered by some historians to be a "proto-gun" because its projectiles did not occlude the barrel.[15] There was also another "proto-gun" called the eruptor, according to Joseph Needham, which did not have a lance but still did not shoot projectiles which occluded the barrel.[16]

Transition to true guns

[edit]

In due course, the proportion of saltpeter in the propellant was increased to maximise its explosive power.[29] To better withstand that explosive power, the paper and bamboo of which fire-lance barrels were originally made came to be replaced by metal.[23] And to take full advantage of that power, the shrapnel came to be replaced by projectiles whose size and shape filled the barrel more closely.[29] Fire lance barrels made of metal appeared by 1276.[30] Earlier in 1259 a pellet wad that filled the barrel was recorded to have been used as a fire lance projectile, making it the first recorded bullet in history.[27] With this, the three basic features of a gun were put in place: a barrel made of metal, high-nitrate gunpowder, and a projectile which totally occludes the muzzle so that the powder charge exerts its full potential in propellant effect.[31] The metal barrel fire lances began to be used without the lance and became guns by the late 13th century.[27]

Guns such as the hand cannon were being used in the Yuan dynasty by the 1280s.[32] Surviving cannons such as the Heilongjiang hand cannon and the Xanadu Gun have been found dating to the late 13th century and possibly earlier in the early 13th century.[33]

In 1287, the Yuan dynasty deployed Jurchen troops with hand cannons to put down a rebellion by the Mongol prince Nayan.[32] The History of Yuan records that the cannons of Li Ting's soldiers "caused great damage" and created "such confusion that the enemy soldiers attacked and killed each other."[34] The hand cannons were used again in the beginning of 1288. Li Ting's "gun-soldiers" or chongzu (銃卒) carried the hand cannons "on their backs". The passage on the 1288 battle is also the first to use the name chong (銃) with the metal radical jin (金) for metal-barrel firearms. Chong was used instead of the earlier and more ambiguous term huo tong (fire tube; 火筒), which may refer to the tubes of fire lances, proto-cannons, or signal flares.[35] Hand cannons may have been used in the Mongol invasions of Japan. Japanese descriptions of the invasions mention iron and bamboo pao causing "light and fire" and emitting 2–3,000 iron bullets.[36] The Nihon Kokujokushi, written around 1300, mentions huo tong (fire tubes) at the Battle of Tsushima in 1274 and the second coastal assault led by Holdon in 1281. The Hachiman Gudoukun of 1360 mentions iron pao "which caused a flash of light and a loud noise when fired."[37] The Taiheki of 1370 mentions "iron pao shaped like a bell."[37]

Spread

[edit]

The exact nature of the spread of firearms and its route is uncertain. One theory is that gunpowder and cannons arrived in Europe via the Silk Road through the Middle East.[38][39] Hasan al-Rammah had already written about fire lances in the 13th century, so proto-guns were known in the Middle East at that point.[40] Another theory is that it was brought to Europe during the Mongol invasion in the first half of the 13th century.[38][39]

The earliest depiction of a cannon in Europe dates to 1326 and evidence of firearm production can be found in the following year.[8] The first recorded use of gunpowder weapons in Europe was in 1331 when two mounted German knights attacked Cividale del Friuli with gunpowder weapons of some sort.[41][42] By 1338 hand cannons were in widespread use in France.[43] English Privy Wardrobe accounts list "ribaldis", a type of cannon, in the 1340s, and siege guns were used by the English at Calais in 1346.[44] Early guns and the men who used them were often associated with the devil and the gunner's craft was considered a black art, a point reinforced by the smell of sulfur on battlefields created from the firing of guns along with the muzzle blast and accompanying flash.[45]

Around the late 14th century in Europe, smaller and portable hand-held cannons were developed, creating in effect the first smooth-bore personal firearm. In the late 15th century the Ottoman Empire used firearms as part of its regular infantry. In the Middle East, the Arabs seem to have used the hand cannon to some degree during the 14th century.[14] Cannons are attested in India starting from 1366.[46]

The Joseon kingdom in Korea learned how to produce gunpowder from China by 1372[6] and started producing cannons by 1377.[47] In Southeast Asia, Đại Việt soldiers used hand cannons at the very latest by 1390 when they employed them in killing Champa king Che Bong Nga.[48] Chinese observer recorded the Javanese use of hand cannon for marriage ceremony in 1413 during Zheng He's voyage.[49][50] Hand guns were utilized effectively during the Hussite Wars.[51] Japan knew of gunpowder due to the Mongol invasions during the 13th century, but did not acquire a cannon until a monk took one back to Japan from China in 1510,[52] and guns were not produced until 1543, when the Portuguese introduced matchlocks which were known as tanegashima to the Japanese.[53]

Gunpowder technology entered Java in the Mongol invasion of Java (1293 A.D.).[54]: 1–2 [55][56]: 220 Majapahit under Mahapatih (prime minister) Gajah Mada utilized gunpowder technology obtained from the Yuan dynasty for use in the naval fleet.[57]: 57 During the following years, the Majapahit army have begun producing cannons known as cetbang. Early cetbang (also called Eastern-style cetbang) resembled Chinese cannons and hand cannons. Eastern-style cetbangs were mostly made of bronze and were front-loaded cannons. It fires arrow-like projectiles, but round bullets and co-viative projectiles[58] can also be used. These arrows can be solid-tipped without explosives, or with explosives and incendiary materials placed behind the tip. Near the rear, there is a combustion chamber or room, which refers to the bulging part near the rear of the gun, where the gunpowder is placed. The cetbang is mounted on a fixed mount, or as a hand cannon mounted on the end of a pole. There is a tube-like section on the back of the cannon. In the hand cannon-type cetbang, this tube is used as a socket for a pole.[59]: 94

Arquebus and musket

[edit]

The arquebus was a firearm that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire in the early 15th century.[60] Its name is derived from the German word Hackenbüchse. It originally described a hand cannon with a lug or hook on the underside for stabilizing the weapon, usually on defensive fortifications.[61] In the early 1500s, heavier variants known as "muskets" that were fired from resting Y-shaped supports appeared. The musket was able to penetrate heavy armor, and as a result armor declined, which also made the heavy musket obsolete. Although there is relatively little to no difference in design between arquebus and musket except in size and strength, it was the term musket which remained in use up into the 1800s.[62] It may not be completely inaccurate to suggest that the musket was in its fabrication simply a larger arquebus. At least on one occasion the musket and arquebus have been used interchangeably to refer to the same weapon,[63] and even referred to as an "arquebus musket."[64] A Habsburg commander in the mid-1560s once referred to muskets as "double arquebuses."[65]

A shoulder stock[66] was added to the arquebus around 1470 and the matchlock mechanism sometime before 1475. The matchlock arquebus was the first firearm equipped with a trigger mechanism[12][67] and the first portable shoulder-arms firearm.[68] Before the matchlock, handheld firearms were fired from the chest, tucked under one arm, while the other arm maneuvered a hot pricker to the touch hole to ignite the gunpowder.[69]

The Ottomans may have used arquebuses as early as the first half of the 15th century during the Ottoman–Hungarian wars of 1443–1444.[70] The arquebus was used in substantial numbers during the reign of king Matthias Corvinus of Hungary (r. 1458–1490).[71] Arquebuses were used by 1472 by the Spanish and Portuguese at Zamora. Likewise, the Castilians used arquebuses as well in 1476.[72] Later, a larger arquebus known as a musket was used for breaching heavy armor, but this declined along with heavy armor. Matchlock firearms continued to be called musket.[73] They were used throughout Asia by the mid-1500s.[74][75][76][77]

Transition to classic guns

[edit]Guns reached their "classic" form in the 1480s. The "classic gun" is so called because of the long duration of its design, which was longer, lighter, more efficient, and more accurate compared to its predecessors 30 years prior. The design persisted for nearly 300 years and cannons of the 1480s show little variation from as well as surprising similarity with cannons three centuries later in the 1750s. This 300-year period during which the classic gun dominated gives it its moniker.[19]

The classic gun differed from older generations of firearms through an assortment of improvements. Their longer length-to-bore ratio imparted more energy into the shot, enabling the projectile to shoot further. They were also lighter since the barrel walls were thinner, allowing faster dissipation of heat. They no longer needed the help of a wooden plug to load since they offered a tighter fit between projectile and barrel, further increasing the accuracy of firearms[79] – and were deadlier due to developments such as gunpowder corning and iron shot.[80]

Modern guns

[edit]Several developments in the 19th century led to the development of modern guns.

In 1815, Joshua Shaw invented percussion caps, which replaced the flintlock trigger system. The new percussion caps allowed guns to shoot reliably in any weather condition.[81]

In 1835, Casimir Lefaucheux invented the first practical breech loading firearm with a cartridge. The new cartridge contained a conical bullet, a cardboard powder tube, and a copper base that incorporated a primer pellet.[82]

Rifles

[edit]

While rifled guns did exist prior to the 19th century in the form of grooves cut into the interior of a barrel, these were considered specialist weapons and limited in number.[73]

The rate of fire of handheld guns began to increase drastically. In 1836, Johann Nicolaus von Dreyse invented the Dreyse needle gun, a breech-loading rifle which increased the rate of fire to six times that of muzzle loading weapons.[82] In 1854, Volcanic Repeating Arms produced a rifle with a self-contained cartridge.[83]

In 1849, Claude-Étienne Minié invented the Minié ball, the first projectile that could easily slide down a rifled barrel, which made rifles a viable military firearm, ending the smoothbore musket era.[84] Rifles were deployed during the Crimean War with resounding success and proved vastly superior to smoothbore muskets.[84]

In 1860, Benjamin Tyler Henry created the Henry rifle, the first reliable repeating rifle.[85] An improved version of the Henry rifle was developed by Winchester Repeating Arms Company in 1873, known as the Model 1873 Winchester rifle.[85]

Smokeless powder was invented in 1880 and began replacing gunpowder, which came to be known as black powder.[86] By the start of the 20th century, smokeless powder was adopted throughout the world and black powder, what was previously known as gunpowder, was relegated to hobbyist usage.[87]

Machine guns

[edit]

In 1861, Richard Jordan Gatling invented the Gatling gun, the first successful machine gun, capable of firing 200 gunpowder cartridges in a minute. It was fielded by the Union forces during the American Civil War in the 1860s.[88] In 1884, Hiram Maxim invented the Maxim gun, the first single-barreled machine gun.[88]

The world's first submachine gun (a fully automatic firearm which fires pistol cartridges) able to be maneuvered by a single soldier is the MP 18.1, invented by Theodor Bergmann. It was introduced into service in 1918 by the German Army during World War I as the primary weapon of the Stosstruppen (assault groups specialized in trench combat).[citation needed]

In civilian use, the captive bolt pistol is used in agriculture to humanely stun farm animals for slaughter.[89]

The first assault rifle was introduced during World War II by the Germans, known as the StG44. It was the first firearm to bridge the gap between long range rifles, machine guns, and short range submachine guns. Since the mid-20th century, guns that fire beams of energy rather than solid projectiles have been developed, and also guns that can be fired by means other than the use of gunpowder.[citation needed]

Operating principle

[edit]Most guns use compressed gas confined by the barrel to propel the bullet up to high speed, though devices operating in other ways are sometimes called guns. In firearms the high-pressure gas is generated by combustion, usually of gunpowder. This principle is similar to that of internal combustion engines, except that the bullet leaves the barrel, while the piston transfers its motion to other parts and returns down the cylinder. As in an internal combustion engine, the combustion propagates by deflagration rather than by detonation, and the optimal gunpowder, like the optimal motor fuel, is resistant to detonation. This is because much of the energy generated in detonation is in the form of a shock wave, which can propagate from the gas to the solid structure and heat or damage the structure, rather than staying as heat to propel the piston or bullet. The shock wave at such high temperature and pressure is much faster than that of any bullet, and would leave the gun as sound either through the barrel or the bullet itself rather than contributing to the bullet's velocity.[90][91]

Components

[edit]Barrel

[edit]

Barrel types include rifled—a series of spiraled grooves or angles within the barrel—when the projectile requires an induced spin to stabilize it, and smoothbore when the projectile is stabilized by other means or rifling is undesired or unnecessary. Typically, interior barrel diameter and the associated projectile size is a means to identify gun variations. Bore diameter is reported in several ways. The more conventional measure is reporting the interior diameter (bore) of the barrel in decimal fractions of the inch or in millimetres. Some guns—such as shotguns—report the weapon's gauge (which is the number of shot pellets having the same diameter as the bore produced from one English pound (454g) of lead) or—as in some British ordnance—the weight of the weapon's usual projectile.[citation needed]

Projectile

[edit]A gun projectile may be a simple, single-piece item like a bullet, a casing containing a payload like a shotshell or explosive shell, or complex projectile like a sub-caliber projectile and sabot. The propellant may be air, an explosive solid, or an explosive liquid. Some variations like the Gyrojet and certain other types combine the projectile and propellant into a single item.[citation needed]

Types

[edit]Military

[edit]Handguns

[edit]- Handgun

- Derringer

- Pistol

- Revolver

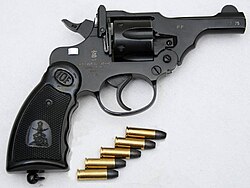

IOF .32 Revolver chambered in .32 S&W Long

Smith & Wesson "Military and Police" revolver

Hunting

[edit]Machine guns

[edit]

Autocannon

[edit]Artillery

[edit]Tank

[edit]Rescue equipment

[edit]Training and entertainment

[edit]- Airsoft gun

- Cap gun

- Drill Purpose Rifle

- Nerf gun

- Paintball gun

- Potato cannon

- Prop gun

- Spud gun

- Water gun

Directed-energy weapons

[edit]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Chambers Dictionary, Allied Chambers – 199, page 717

- ^ Merriam-Webster Dictionary - gun

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 51.

- ^ a b c Needham 1986, p. 10.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 104.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 307.

- ^ Nicolle 1983, p. 18.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 75.

- ^ Merriam-Webster, Inc. (1990). The Merriam-Webster's New Book of Word Histories. Basic Books. pg.207

- ^ a b Kelly 2004, p. 31.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 30.

- ^ a b Phillips 2016.

- ^ "Definition of GUN". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 13 August 2023.

- ^ a b Chase 2003, p. 1.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 37.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 9.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 17.

- ^ McLachlan 2010, p. 8.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 106.

- ^ Buchanan 2006, p. 2 "With its ninth century AD origins in China, the knowledge of gunpowder emerged from the search by alchemists for the secrets of life, to filter through the channels of Middle Eastern culture, and take root in Europe with consequences that form the context of the studies in this volume."

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 7 "Without doubt it was in the previous century, around +850, that the early alchemical experiments on the constituents of gunpowder, with its self-contained oxygen, reached their climax in the appearance of the mixture itself."

- ^ a b Chase 2003, pp. 31–32

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 222.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 31.

- ^ Lorge 2008, p. 33-34.

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 52.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 46.

- ^ a b Crosby 2002, p. 99.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 228.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 10

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 53.

- ^ Andrade 2016, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 294.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 304.

- ^ Purton 2010, p. 109.

- ^ a b Needham 1986, p. 295.

- ^ a b Norris 2003:11

- ^ a b Chase 2003:58

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 84.

- ^ DeVries, Kelly (1998). "Gunpowder Weaponry and the Rise of the Early Modern State". War in History. 5 (2): 130. doi:10.1177/096834459800500201. JSTOR 26004330. S2CID 56194773.

- ^ von Kármán, Theodore (1942). "The Role of Fluid Mechanics in Modern Warfare". Proceedings of the Second Hydraulics Conference: 15–29.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 77.

- ^ David Nicolle, Crécy 1346: Triumph of the longbow, Osprey Publishing; June 25, 2000; ISBN 978-1-85532-966-9.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Khan 2004, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. [page needed].

- ^ Tran 2006, p. 75.

- ^ Mayers (1876). "Chinese explorations of the Indian Ocean during the fifteenth century". The China Review. IV: p. 178.

- ^ Manguin 1976, p. 245.

- ^ "First use of hand guns in war". Guinness World Records. 2023-01-19. Retrieved 2023-01-19.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 430.

- ^ Lidin 2002, pp. 1–14.

- ^ Schlegel, Gustaaf (1902). "On the Invention and Use of Fire-Arms and Gunpowder in China, Prior to the Arrival of European". T'oung Pao. 3: 1–11.

- ^ Lombard, Denys (1990). Le carrefour javanais. Essai d'histoire globale (The Javanese Crossroads: Towards a Global History) Vol. 2. Paris: Editions de l'Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales. Page 178.

- ^ Reid, Anthony (1993). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680. Volume Two: Expansion and Crisis. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- ^ Pramono, Djoko (2005). Budaya Bahari. Gramedia Pustaka Utama. ISBN 9789792213768.

- ^ A type of scatter bullet — when shot it spews fire, splinters and bullets, and can also be arrows. The characteristic of this projectile is that the bullet does not cover the entire bore of the barrel. Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 9 and 220.

- ^ Averoes, Muhammad (2020). Antara Cerita dan Sejarah: Meriam Cetbang Majapahit. Jurnal Sejarah, 3(2), 89 - 100.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 443.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 426.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 61.

- ^ Adle 2003, p. 475.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 165.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 92.

- ^ Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1991). "The Nature of Handguns in Mughal India: 16th and 17th Centuries". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 52: 378–389. JSTOR 44142632.

- ^ Petzal 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Partington 1999, p. xxvii.

- ^ Arnold 2001, p. 75.

- ^ Ágoston, Gábor (2014). "Firearms and Military Adaptation: The Ottomans and the European Military Revolution, 1450–1800". Journal of World History. 25 (1): 85–124. doi:10.1353/jwh.2014.0005. ISSN 1527-8050. S2CID 143042353.

- ^ Bak 1982, pp. 125–40.

- ^ Partington 1999, p. 123.

- ^ a b Arnold 2001, p. 75-78.

- ^ Khan 2004, p. 131.

- ^ Tran 2006, p. 107.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 169.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 171.

- ^ "Pair of Miquelet Pistols". Metropolitan Museum of Art website.

- ^ Andrade 2016, pp. 104–106.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 107.

- ^ Willbanks 2004, p. 11.

- ^ a b Willbanks 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Willbanks 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b Willbanks 2004, p. 12.

- ^ a b Willbanks 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 294.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 232.

- ^ a b Chase 2003, p. 202.

- ^ "Captive Bolt Stunning Equipment and the Law – How it applies to you". Archived from the original on 2014-04-05.

- ^ Dunlap, Roy F. (June 1963). Gunsmithing. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0770-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "How Guns Work". Pew Pew Tactical. 2 April 2021.

References

[edit]- Adle, Chahryar (2003), History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in Contrast: from the Sixteenth to the Mid-Nineteenth Century

- Ágoston, Gábor (2005), Guns for the Sultan: Military Power and the Weapons Industry in the Ottoman Empire, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60391-1

- Agrawal, Jai Prakash (2010), High Energy Materials: Propellants, Explosives and Pyrotechnics, Wiley-VCH

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Arnold, Thomas F. (2001), History of Warfare: The Renaissance at War, London: Cassell & Co, ISBN 978-0-304-35270-8

- Bak, J. M. (1982), Hunyadi to Rákóczi: War and Society in Late Medieval and Early Modern Hungary

- Benton, Captain James G. (1862). A Course of Instruction in Ordnance and Gunnery (2nd ed.). West Point, New York: Thomas Publications. ISBN 978-1-57747-079-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Breverton, Terry (2012), Breverton's Encyclopedia of Inventions

- Brown, G. I. (1998), The Big Bang: A History of Explosives, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7509-1878-7.

- Buchanan, Brenda J. (2006), "Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History", Technology and Culture, 49 (3), Aldershot: Ashgate: 785–86, doi:10.1353/tech.0.0051, ISBN 978-0-7546-5259-5, S2CID 111173101

- Chase, Kenneth (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9.

- Cocroft, Wayne (2000), Dangerous Energy: The archaeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture, Swindon: English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-85074-718-5

- Cook, Haruko Taya (2000), Japan at War: An Oral History, Phoenix Press

- Cowley, Robert (1993), Experience of War, Laurel.

- Cressy, David (2013), Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder, Oxford University Press

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002), Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-79158-8.

- Curtis, W. S. (2014), Long Range Shooting: A Historical Perspective, WeldenOwen.

- Earl, Brian (1978), Cornish Explosives, Cornwall: The Trevithick Society, ISBN 978-0-904040-13-5.

- Easton, S. C. (1952), Roger Bacon and His Search for a Universal Science: A Reconsideration of the Life and Work of Roger Bacon in the Light of His Own Stated Purposes, Basil Blackwell

- Ebrey, Patricia B. (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-43519-2

- Grant, R.G. (2011), Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare, DK Publishing.

- Hadden, R. Lee. 2005. "Confederate Boys and Peter Monkeys." Armchair General. January 2005. Adapted from a talk given to the Geological Society of America on 25 March 2004.

- Harding, Richard (1999), Seapower and Naval Warfare, 1650–1830, UCL Press Limited

- Smee, Harry (2020), Gunpowder and Glory

- Haw, Stephen G. (2013), Cathayan Arrows and Meteors: The Origins of Chinese Rocketry

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2001), "Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources", History of Science and Technology in Islam, retrieved 23 July 2007.

- Hobson, John M. (2004), The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation, Cambridge University Press.

- Johnson, Norman Gardner. "explosive". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago.

- Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-03718-6.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1996), "Coming of Gunpowder to the Islamic World and North India: Spotlight on the Role of the Mongols", Journal of Asian History, 30: 41–45.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004), Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India, Oxford University Press

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval India, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0-8108-5503-8

- Kinard, Jeff (2007), Artillery An Illustrated History of its Impact

- Konstam, Angus (2002), Renaissance War Galley 1470-1590, Osprey Publisher Ltd..

- Lee, R. Geoffrey (1981). Introduction to Battlefield Weapons Systems and Technology. Oxford: Brassey's Defence Publishers. ISBN 0080270433.

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 978-981-05-5380-7

- Lidin, Olaf G. (2002), Tanegashima – The Arrival of Europe in Japan, Nordic Inst of Asian Studies, ISBN 978-8791114120

- Lorge, Peter (2005), Warfare in China to 1600, Routledge

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Lu, Gwei-Djen (1988), "The Oldest Representation of a Bombard", Technology and Culture, 29 (3): 594–605, doi:10.2307/3105275, JSTOR 3105275, S2CID 112733319

- Lu, Yongxiang (2015), A History of Chinese Science and Technology 2

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1976). "L'Artillerie legere nousantarienne: A propos de six canons conserves dans des collections portugaises" (PDF). Arts Asiatiques. 32: 233–268. doi:10.3406/arasi.1976.1103. S2CID 191565174.

- May, Timothy (2012), The Mongol Conquests in World History, Reaktion Books

- McLachlan, Sean (2010), Medieval Handgonnes

- McNeill, William Hardy (1992), The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community, University of Chicago Press.

- Morillo, Stephen (2008), War in World History: Society, Technology, and War from Ancient Times to the Present, Volume 1, To 1500, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-052584-9

- Needham, Joseph (1971), Science and Civilization in China, Volume 4 Part 3, Cambridge University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1976), Science and Civilization in China, Volume 5 Part 3, Cambridge University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1980), Science & Civilisation in China, Volume 5 Part 4, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-08573-1

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, Volume 5 Part 7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3

- Nicolle, David (1990), The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane

- Nicolle, David (1983), Armies of the Ottoman Turks 1300-1774

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2006), The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000–1650: an Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization, Vol 1, A-K, vol. 1, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-33733-8

- Norris, John (2003), Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300–1600, Marlborough: The Crowood Press.

- Padmanabhan, Thanu (2019), The Dawn of Science: Glimpses from History for the Curious Mind, Bibcode:2019dsgh.book.....P

- Partington, J. R. (1960), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer & Sons.

- Partington, J. R. (1999), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0

- Patrick, John Merton (1961), Artillery and warfare during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Utah State University Press.

- Pauly, Roger (2004), Firearms: The Life Story of a Technology, Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Perrin, Noel (1979), Giving up the Gun, Japan's reversion to the Sword, 1543–1879, Boston: David R. Godine, ISBN 978-0-87923-773-8

- Petzal, David E. (2014), The Total Gun Manual (Canadian edition), WeldonOwen.

- Phillips, Henry Prataps (2016), The History and Chronology of Gunpowder and Gunpowder Weapons (c.1000 to 1850), Notion Press

- Pregadio, Fabrizio (2011), The Seal of the Unity of the Three

- Purton, Peter (2009), A History of the Early Medieval Siege c. 450–1200, The Boydell Press

- Purton, Peter (2010), A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 1200–1500, Boydell Press, ISBN 978-1-84383-449-6

- Robins, Benjamin (1742), New Principles of Gunnery

- Romane, Julian (2020), The First & Second Italian Wars 1494-1504

- Rose, Susan (2002), Medieval Naval Warfare 1000–1500, Routledge

- Roy, Kaushik (2015), Warfare in Pre-British India, Routledge

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977a), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (2): 153–173 (153–157)

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977b), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (3): 213–237 (226–228)

- Tran, Nhung Tuyet (2006), Viêt Nam Borderless Histories, University of Wisconsin Press.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003), Fighting Ships Far East (2: Japan and Korea AD 612–1639, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84176-478-8

- Urbanski, Tadeusz (1967), Chemistry and Technology of Explosives, vol. III, New York: Pergamon Press.

- Villalon, L. J. Andrew (2008), The Hundred Years War (part II): Different Vistas, Brill Academic Pub, ISBN 978-90-04-16821-3

- Wagner, John A. (2006), The Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-32736-0

- Watson, Peter (2006), Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud, Harper Perennial (2006), ISBN 978-0-06-093564-1

- Wilkinson, Philip (9 September 1997), Castles, Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 978-0-7894-2047-3

- Wilkinson-Latham, Robert (1975), Napoleon's Artillery, France: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-0-85045-247-1

- Willbanks, James H. (2004), Machine guns: an illustrated history of their impact, ABC-CLIO, Inc.

- Williams, Anthony G. (2000), Rapid Fire, Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing Ltd., ISBN 978-1-84037-435-3

- Kouichiro, Hamada (2012), 日本人はこうして戦争をしてきた

- Tatsusaburo, Hayashiya (2005), 日本の歴史12 - 天下一統

Etymology and Terminology

Etymology

The English word "gun" derives from Middle English gonne or gunne, first recorded in the mid-14th century to denote a mechanical device for hurling stones or other projectiles, such as a trebuchet or early cannon.[5][6] The term's precise origin remains uncertain and debated among linguists, with no definitive consensus on its root language or initial application.[6] A prominent theory traces "gun" to a colloquial shortening of the Old Norse-derived feminine given name Gunnhild (or variants like Gunilda or Gunnild), composed of elements gunnr ("war") and hildr ("battle"). This name was reportedly bestowed upon a specific 14th-century siege engine, such as the "Domina Gunilda" mentioned in monastic chronicles from the siege of Berwick in 1333, personifying the weapon in a manner akin to naming ships or engines after notable figures.[5][7][8] As gunpowder weapons proliferated in Europe from the late 14th century, the term extended to describe tube-shaped firearms that expelled missiles via explosive propulsion, supplanting earlier descriptors like "handgonne."[5][8] Alternative hypotheses include onomatopoeic imitation of the firing sound or borrowings from Low German gune (mechanism) or French engaine (trick or engine), but these lack the historical specificity of the Gunnhild attribution and are less supported by early textual evidence.[6] By the 15th century, "gun" had standardized in English inventories of ordnance, reflecting its shift from siege apparatus to portable arms.[5]Definitions and Classifications

A gun is a ranged weapon consisting of a metal tube, or barrel, through which a mechanically accelerated explosive-driven projectile is propelled toward a target, typically by the rapid expansion of high-pressure gases generated by igniting a propellant charge such as gunpowder.[1] This definition encompasses both portable small arms and larger mounted or vehicle-borne systems, distinguishing guns from other projectile weapons like bows or catapults that rely on mechanical or elastic energy rather than chemical combustion.[9] The term "gun" is frequently used synonymously with "firearm," particularly for man-portable weapons, though "firearm" in legal contexts like U.S. federal law specifically denotes devices expelling projectiles via explosive action, excluding non-explosive alternatives such as air guns or paintball markers unless modified.[1][10] Guns are classified by multiple technical and functional criteria, including size, barrel configuration, operating mechanism, firing mode, and caliber, which influence range, accuracy, and lethality. By size and portability, they divide into handguns—compact weapons designed for one-handed firing, such as pistols and revolvers—and long guns, which include shoulder-fired rifles and shotguns requiring two-handed support for stability.[11][3] Rifles feature rifled barrels with spiral grooves imparting spin to projectiles for improved accuracy and range, while shotguns typically have smoothbore barrels optimized for dispersing multiple pellets or slugs at short distances.[10][12] Operating mechanisms further categorize guns as manually operated (e.g., bolt-action, lever-action, or pump-action, requiring user intervention to cycle ammunition), semi-automatic (which reload and rechamber rounds automatically after each shot but fire only on trigger pull), or fully automatic (machine guns that continue firing as long as the trigger is held and ammunition is available).[13][3] Caliber, denoting the internal diameter of the barrel or the projectile's nominal diameter, standardizes ammunition compatibility and performance; common handgun calibers include 9mm (approximately 0.354 inches) and .45 ACP, while rifle calibers range from .22 (small game) to .50 BMG for anti-materiel roles.[14][15] Larger guns, such as artillery pieces, are classified by bore diameter in millimeters or inches (e.g., 105mm howitzers) and role (direct-fire guns versus indirect-fire howitzers), but these exceed small-arms portability and are crew-served.[16]| Classification Criterion | Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Size/Portability | Handguns (pistols, revolvers) | One-handed operation; short barrels (typically under 6 inches); suited for close-range self-defense.[3] |

| Long guns (rifles, shotguns) | Shoulder-fired; longer barrels (16+ inches for rifles); enhanced velocity and accuracy.[11] | |

| Barrel Type | Rifled | Spiral grooves for projectile stabilization; used in rifles for precision.[12] |

| Smoothbore | No rifling; disperses shot patterns; common in shotguns.[10] | |

| Firing Mode | Semi-automatic | One shot per trigger pull; self-reloading.[3] |

| Fully automatic | Continuous fire while trigger depressed; restricted in many jurisdictions.[13] | |

| Caliber | Small (.22–.38) | Low recoil; training or varmint use.[14] |

| Medium (9mm–.45) | Balanced for self-defense; most common handgun rounds.[14] | |

| Large (.50+) | High power; anti-vehicle or long-range.[15] |

History

Origins and Early Development

The origins of the gun lie in the invention of gunpowder in 9th-century China, where Taoist alchemists experimenting with elixirs of immortality discovered an explosive mixture of saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal.[17] This compound's earliest documented military applications appear in the Wujing Zongyao, a 1044 AD Chinese text that records formulas for incendiary devices and bombs propelled by gunpowder.[18] Initially used for fireworks and grenades, gunpowder's potential for propulsion emerged during the Song dynasty's conflicts with northern invaders, enabling the creation of weapons that harnessed controlled explosions to project force. Early development progressed from fire lances—bamboo or metal tubes affixed to spears and filled with gunpowder, which spewed flames, shrapnel, and occasionally proto-projectiles—deployed by Song forces by around 1150 AD against Jurchen and Mongol armies.[19] These devices, precursors to true firearms, evolved into metal-barreled cannons by the 12th century, with bulbous wrought-iron tubes capable of launching stone or metal shot over distances, as evidenced by archaeological finds and textual accounts from the era.[20] The transition to handheld variants occurred in the late 13th century, yielding hand cannons: short, vase-shaped metal guns loaded through the muzzle with powder and projectile, ignited via a touch hole, representing the first portable firearms designed for individual use in combat.[21] This Chinese innovation spread westward through Mongol conquests and trade routes, reaching the Islamic world and Europe by the 13th century, where it spurred parallel developments in cannon design but retained core principles of gunpowder propulsion.[22] Early guns prioritized explosive power over accuracy or rate of fire, with effectiveness limited by unreliable ignition, barrel fractures, and the need for skilled operators to manage powder charges.[23] Archaeological evidence, such as dated hand cannon artifacts from Yuan dynasty sites, confirms these weapons' role in siege warfare and infantry tactics by the 1280s.[20]Evolution of Mechanisms

The matchlock mechanism, whose precise origins remain unclear and debated, possibly originating in the Ottoman Empire before emerging in Europe during the early 15th century, marked the first widespread mechanical ignition system for handheld firearms, employing a serpentine arm to lower a slow-burning match onto priming powder in an open pan via trigger pull, thereby freeing the shooter's hands for aiming.[24] [25] This advance overcame the limitations of manual ignition with linstocks or hot irons but remained vulnerable to dampness extinguishing the match.[25] The wheellock, introduced in the early 16th century, addressed weather sensitivity by generating sparks through a spring-tensioned, serrated wheel spinning against pyrite locked in a vise, akin to a rudimentary lighter, enabling self-ignition without external flame.[24] Though complex and costly, it paved the way for further refinements like the snaphance and doglock, which separated sparking and pan-covering actions.[26] The flintlock, evolving from these in the early 16th century and perfected by French gunsmith Marin le Bourgeoys around 1610, integrated flint held in a pivoting cock that hammer-struck a hinged steel frizzen to produce sparks while uncovering the pan, offering superior reliability and simplicity that dominated military and civilian arms for over 200 years.[26] The percussion cap system, pioneered by Scottish cleric Alexander Forsyth's 1807 patent for detonating compounds and commercialized in copper caps by the 1820s, shifted ignition to a hammer impacting a fulminate-filled cap on a hollow nipple, igniting the main charge via a confined flash channel and eliminating open pans entirely.[27] This weatherproof design accelerated firing rates and reliability, supplanting flintlocks in armies by the 1840s and enabling widespread adoption of revolvers like Samuel Colt's 1836 Paterson.[27] Mid-19th-century metallic cartridges integrated percussion priming into self-contained units—rimfire with the primer at the case rim (e.g., .22 Short in 1857) and centerfire with an anvil-struck primer in the case head—facilitating breech-loading and eliminating loose powder handling.[28] [29] Early systems like pinfire (1846) preceded rimfire, but centerfire cartridges, refined post-1860, supported higher pressures and repeating actions via levers, bolts, or slides.[29] Late 19th-century innovations introduced self-loading mechanisms harnessing recoil or propellant gas to automate extraction, ejection, and chambering, as in Hugo Borchardt's 1893 toggle-locked pistol or John Browning's gas-operated designs from 1890s onward, evolving into semi-automatic rifles and full-automatic machine guns by World War I.[30] These harnessed cartridge energy for cycling, with blowback relying on bolt inertia, delayed blowback adding locks, and gas taps diverting pressure to pistons or operating rods, vastly increasing sustained fire rates while requiring controlled feeding from magazines.[30]Industrialization and Mass Production

The industrialization of gun manufacturing began in the early 19th century in the United States, transitioning from artisanal craftsmanship to factory-based production using interchangeable parts and specialized machine tools. This shift was primarily driven by government contracts for military armaments, which necessitated scalable output to equip expanding armies. Eli Whitney, inventor of the cotton gin, secured a U.S. government contract in 1798 to produce 10,000 flintlock muskets within two years, establishing a factory near New Haven, Connecticut, where he implemented early concepts of interchangeable components to enable assembly-line-like efficiency.[31] Although Whitney's muskets were not fully interchangeable upon inspection and delivery was delayed until 1809, his demonstration before Congress—disassembling ten rifles, mixing parts, and reassembling them—popularized the "American System of Manufacturing," which emphasized precision tooling and standardization.[31] [32] Federal armories, particularly Springfield Armory established in 1794, advanced this system through the development of gauges and mid-19th-century machines for forging, milling, and rifling barrels, powered initially by water and later steam.[33] These innovations allowed for uniform production, with Springfield producing hundreds of thousands of rifles during conflicts like the Civil War, contributing to the Union's total output exceeding 1.5 million small arms from armories and private contractors.[34] Connecticut Valley factories along the river harnessed hydraulic power for mass-producing components, fostering machine tool advancements that extended to other industries.[35] By the 1850s, American gun manufacturing had gained international renown, prompting British observers to study its efficiency for their own adoption.[36] Samuel Colt further propelled mass production with his 1836 patent for the revolving-cylinder revolver, establishing a factory in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1847 after receiving a U.S. Army order for 1,000 Colt Walker revolvers based on Texas Ranger specifications.[37] [38] Colt's operations integrated assembly techniques, specialized machinery, and a division of labor, enabling output of thousands of units annually and creating a civilian market beyond military needs.[39] This model democratized access to reliable repeating firearms, with production scaling during the Mexican-American War and westward expansion, where revolvers became essential tools.[40] The proliferation of such factories not only met wartime demands but also laid the groundwork for broader industrial mechanization, as gun-making precision drove innovations in metalworking and automation throughout the 19th century.[41]20th and 21st Century Advancements

The 20th century marked a shift toward semi-automatic and automatic firearms, propelled by military necessities in global conflicts. John Browning's designs, including the 1911 semi-automatic pistol adopted by the U.S. Army in 1911 and the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) introduced in 1918, enabled sustained fire rates previously unattainable with manual actions.[42] The BAR, capable of selective fire, fired 20-round magazines at up to 600 rounds per minute, influencing squad-level tactics.[42] Submachine guns proliferated during World War I, with Hugo Schmeisser's MP18, chambered in 9mm Parabellum and using simple blowback operation, entering service in 1918 to provide close-quarters automatic fire.[43] World War II accelerated innovation, as stamped-metal constructions like the British Sten gun, produced from 1941 onward in quantities exceeding 4 million units, demonstrated cost-effective mass production for irregular forces.[44] The German StG 44 assault rifle, fielded in 1944, introduced intermediate-power cartridges (7.92×33mm Kurz) for balanced range and controllability in full-automatic mode, with over 425,000 produced by war's end.[45] Postwar developments emphasized reliability and logistics. The Soviet AK-47, designed by Mikhail Kalashnikov and adopted in 1949, utilized a long-stroke gas piston and loose tolerances for operation in harsh environments, achieving global proliferation with estimates of over 100 million units manufactured.[42] The U.S. M16 rifle, adopted in 1964 with its 5.56×45mm cartridge and direct impingement gas system, prioritized lightweight construction and accuracy, though early reliability issues in Vietnam prompted refinements like the M16A1 in 1967.[45] Material science advanced firearm durability and weight reduction. Polymer frames emerged in rifles like the Remington Nylon 66 in 1959, but gained prominence in pistols with Gaston Glock's Glock 17 in 1982, using a nylon-based polymer for the frame that reduced weight by approximately 25% compared to all-steel designs while maintaining structural integrity under recoil.[46][47] In the 21st century, modularity enhanced adaptability, building on the AR-15 platform's Picatinny rail system standardized in the 1990s but widely refined post-2000 for attaching optics, lights, and grips without permanent alterations.[48] Designs like the FN SCAR, adopted by U.S. Special Operations in 2009, allowed caliber swaps and barrel changes for mission-specific configurations.[48] Electronic aids, including compact red dot sights and thermal imagers, integrated seamlessly, improving low-light performance and precision; for instance, Aimpoint models reduced target acquisition time by factors of 2-3 in training data.[49] Ammunition advancements, such as polymer-coated bullets introduced in the 2010s, minimized fouling and enhanced feeding reliability in high-round-count scenarios.[50] These evolutions prioritized user ergonomics, reduced logistical burdens, and countered evolving threats like body armor through specialized projectiles.[50]Principles of Operation

Propulsion Mechanics

The propulsion of a projectile in a firearm relies on internal ballistics, the process by which chemical energy from a propellant is converted into the kinetic energy of the bullet through the rapid generation and expansion of high-pressure gases within the barrel. Upon ignition by the primer's impact-sensitive compound, the propellant undergoes deflagration—a subsonic combustion that produces a volume of hot gases far exceeding the initial solid material's space, creating pressures typically ranging from 20,000 to 60,000 psi in modern small arms, depending on caliber and load. These gases exert force on the base of the projectile, accelerating it along the bore while the chamber and barrel contain the pressure until the bullet exits the muzzle.[51][52] Traditional black powder, used in early firearms since the 13th century, consists of approximately 75% potassium nitrate (oxidizer), 15% charcoal (fuel), and 10% sulfur (to lower ignition temperature and accelerate burning). This mixture burns progressively, generating gases primarily carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and water vapor, but produces significant residue and lower pressures (around 10,000-20,000 psi), limiting muzzle velocities to about 1,200-1,500 feet per second in muskets. The slower burn rate allows for a more gradual pressure buildup, but fouling from unburned particles necessitates frequent cleaning and restricts sustained firing rates.[53][54] Modern smokeless powders, introduced in the 1880s by inventors like Paul Vieille with Poudre B (nitrocellulose-based), supplanted black powder due to higher energy density—yielding up to three times the velocity for equivalent masses—and reduced smoke and residue. Single-base variants rely on nitrocellulose gelatinized with solvents like ether-alcohol, while double-base types incorporate nitroglycerin for added power; both deflagrate to produce primarily nitrogen, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen gases under controlled burn rates tailored by grain shape (e.g., flakes, cylinders) to match barrel length and pressure limits. This enables velocities exceeding 3,000 feet per second in high-powered rifles, with pressure curves peaking sharply before declining as the expanding gas volume dilutes the force, optimizing efficiency while minimizing barrel erosion from peak stresses around 50,000-65,000 psi in rifle cartridges.[54][55]Firing Sequences and Safety Features

The firing sequence in a firearm begins when the trigger is pulled, releasing the hammer or striker to strike the firing pin, which impacts the primer in the cartridge base. This detonates the primer compound, producing a spark that ignites the propellant powder inside the cartridge case.[56][57] The burning powder generates rapidly expanding gases, creating high pressure that propels the bullet down the barrel while the case expands against the chamber walls to seal it temporarily.[58][59] Once the bullet exits the muzzle, pressure drops, allowing the sequence to complete without further propulsion.[60] In manual-action firearms, such as bolt-action rifles, the sequence requires operator intervention after each shot: the bolt is manually cycled to extract the spent case, eject it, chamber a new round from the magazine, and recock the firing mechanism.[61] Semi-automatic firearms automate this cycle using recoil or gas energy from the fired round; after ignition and bullet departure, the slide or bolt unlocks, extracts and ejects the empty case via recoil spring or gas piston, strips a new cartridge from the magazine, chambers it, and recocks the hammer or striker for the next trigger pull.[62][63] Fully automatic weapons extend this by using residual gas or recoil to repeat the cycle continuously while the trigger remains depressed, limited by mechanical feed rates and heat buildup.[64] Safety features in firearms encompass both active (user-engaged) and passive (automatic) mechanisms to prevent unintended discharge. Manual safeties, such as thumb levers or cross-bolt designs, physically block the trigger, sear, or hammer movement when engaged, requiring deliberate disengagement before firing.[65][66] Grip safeties, common in 1911-style pistols, interrupt the trigger linkage unless the pistol grip is firmly compressed, adding a tactile activation step.[65] Passive drop safeties, including firing pin blocks, prevent the pin from protruding and striking a primer if the firearm impacts a surface, typically via a spring-loaded plunger that only retracts fully upon trigger pull.[67][68] Additional passive features include disconnectors, which halt firing if the slide is out of battery (not fully forward), ensuring the chamber is aligned before allowing a subsequent shot, and magazine disconnects that block the trigger if the magazine is removed, though these can limit tactical flexibility.[69] Trigger safeties, integrated into the trigger face, require full intentional depression to disengage internal blocks.[70] These mechanisms, tested under standards like those from SAAMI, enhance reliability against inertial forces but do not replace proper handling, as no safety guarantees absolute prevention of accidental discharge.[67]Ballistics and Performance Factors

Ballistics in firearms refers to the study of projectile motion, divided into internal ballistics, which occurs from ignition within the chamber to muzzle exit; external ballistics, governing flight from muzzle to target; and terminal ballistics, describing impact effects on the target.[71][72] Internal ballistics involves propellant combustion generating pressure to accelerate the bullet, with muzzle velocity typically ranging from 300 meters per second for handgun rounds to over 900 meters per second for high-powered rifles, influenced by factors such as powder charge, bullet mass, and barrel length.[71] Longer barrels allow more complete propellant burn, increasing velocity by up to 25-50 meters per second per additional inch in rifles.[73][74] External ballistics determines trajectory under gravity, air resistance, and environmental variables like wind and temperature, with drag coefficient affected by bullet shape and velocity.[75] Rifling—spiral grooves in the barrel—imparts rotational spin to the bullet, typically at rates of 150,000 to 300,000 revolutions per minute, enhancing gyroscopic stability and reducing yaw for improved accuracy over distances exceeding 100 meters.[76][77] Optimal twist rates, such as 1:10 inches for .308 Winchester, match bullet length and mass to prevent tumbling, while mismatched rates can degrade precision by increasing dispersion.[77] Terminal ballistics examines energy transfer upon impact, where rifle projectiles at velocities above 600 meters per second often produce larger temporary cavities via hydrodynamic shock, exceeding those from handgun rounds limited to subsonic or low-supersonic speeds.[78] Empirical gel tests show rifle bullets like 5.56mm NATO creating 15-20 cm penetration with fragmentation, versus 9mm handgun rounds yielding 30-40 cm but narrower channels without yaw-induced expansion.[78] Performance metrics include kinetic energy, calculated as , peaking at 500-2000 joules for rifles compared to 400-600 joules for pistols, though overpenetration risks rise with high-velocity rounds.[78][79] Recoil, a key performance factor, arises from conservation of momentum, with free recoil energy approximated by , where derives from bullet and gas ejection velocities divided by gun mass; a 7.62mm rifle generates 15-20 foot-pounds, manageable with stocks but disruptive in lighter handguns.[80][81] Accuracy further depends on consistent muzzle velocity standard deviation below 15 meters per second and shooter-induced variables like trigger pull, with wind deflection modeled as proportional to crosswind velocity and time of flight squared.[82][74]| Factor | Effect on Performance | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Barrel Length | Increases velocity and range; reduces maneuverability | +30 m/s per inch in rifles[73] |

| Propellant Charge | Higher charge boosts pressure and speed; risks overpressure | Smokeless powder yields 800-1000 m/s in assault rifles[83] |

| Temperature | Elevates burn rate, raising velocity by 1-2 m/s per °C | Cold ammo drops speed 10-20% at -20°C[84] |

| Rifling Twist | Stabilizes longer bullets; too fast induces stress fractures | 1:7 for 62-grain 5.56mm[77] |

Components

Barrel and Chamber

The barrel of a firearm consists of a metal tube through which the projectile travels after ignition of the propellant.[12] It directs the projectile's path and, in rifled barrels, imparts rotational spin via helical grooves known as rifling, which stabilizes the projectile in flight by gyroscopic effects, improving accuracy and range.[85][86] The ridges between these grooves, called lands, contact the projectile to engage the spin.[85] Barrel length influences muzzle velocity, with longer barrels allowing more complete propellant burn and thus higher exit speeds; empirical tests show velocity gains of approximately 20-50 feet per second per inch of added length, varying by cartridge and powder type.[87][88] Shorter barrels reduce velocity but improve maneuverability, while excessive length can introduce drag without proportional gains.[89] Barrels are typically constructed from high-strength steel alloys to withstand peak chamber pressures exceeding 50,000 psi in modern rifles.[90] Many barrels feature chrome lining, applied via electrodeposition after rifling, to enhance resistance to erosion from hot gases and friction, extending service life under high-volume fire.[91][92] This process involves pre-treating the bore for adhesion, then plating a thin chromium layer, though it can slightly reduce inherent accuracy compared to unlined bores due to surface hardness differences.[93] The chamber is the rear portion of the barrel or cylinder that securely holds the cartridge prior to firing, containing the primer, propellant, and projectile until pressure builds to propel the bullet forward.[94] Chamber dimensions are precisely machined to match specific cartridge specifications, ensuring proper headspace—the distance from the face of the bolt or breech to the chamber's datum line—which prevents excessive case expansion or rupture under firing pressures.[95] Variations like fluted or ported chambers aid in gas venting or extraction but are less common in standard designs.[96] In revolvers, multiple chambers form a rotating cylinder, while semi-automatic firearms integrate a single chamber directly into the barrel's breech end.[94]Action and Trigger Mechanisms

The action mechanism of a firearm encompasses the components and processes responsible for loading a cartridge into the chamber, firing the round, extracting the spent casing, and, in repeating firearms, preparing the next round for firing.[97] Manual actions require operator intervention to cycle the mechanism, such as bolt-action rifles where the user manually rotates and pulls back a bolt handle to chamber a round, a design refined in the 19th century for military rifles like the Prussian Dreyse needle gun of 1841, though modern bolt actions dominate precision shooting due to their inherent accuracy from rigid lockup.[98] Lever-action mechanisms, popularized by the Henry rifle in 1860, use a lever beneath the trigger guard to cycle rounds via a tubular magazine, enabling faster follow-up shots in repeating firearms without full disassembly.[99] Pump-action, or slide-action, systems, as in shotguns like the Winchester Model 1897 introduced in 1897, involve sliding a forearm forward and back to eject and load shells, offering reliability in adverse conditions without reliance on gas or recoil energy.[99] Self-loading actions automate cycling using energy from the fired cartridge: semi-automatic firearms fire one round per trigger pull and reload via recoil-operated or gas-operated systems, with blowback designs common in pistols where the bolt recoils against spring tension to eject and chamber rounds, as seen in the Colt M1911 adopted by the U.S. Army in 1911.[3] Gas-operated semi-automatics, like the M1 Garand rifle fielded in 1936, divert propellant gases to drive a piston or operate the bolt directly, enhancing reliability under sustained fire compared to recoil systems that can bind with heavier projectiles.[99] Fully automatic actions, restricted in civilian use in many jurisdictions, continue firing as long as the trigger is held and ammunition is available, typically via selective-fire mechanisms selectable between semi- and full-auto modes, originating in designs like the Maxim gun of 1884 which used toggle-lock recoil.[98] Trigger mechanisms initiate firing by releasing the hammer, striker, or firing pin to strike the primer. Single-action (SA) triggers require manual cocking of the hammer—via slide recoil in semi-automatics or thumb in revolvers—before the trigger performs the sole action of releasing it, providing a lighter, shorter pull for precision, as in the Colt Single Action Army revolver produced since 1873.[100] Double-action (DA) triggers cock and release the hammer in one pull, resulting in a longer, heavier stroke for initial shots, a feature introduced in revolvers like the Adams revolver of 1851, which allowed firing without manual cocking but at the cost of reduced accuracy due to trigger travel.[101] Double-action/single-action (DA/SA) systems, common in pistols like the Beretta 92 adopted by the U.S. military in 1985, start with DA for the first shot and transition to SA for subsequent rounds after slide recoil cocks the hammer, balancing readiness with control.[100] Striker-fired triggers, prevalent in modern polymer-frame pistols like the Glock 17 introduced in 1982, employ a spring-loaded internal striker instead of an external hammer; partial pre-cocking via slide movement shortens the trigger pull, with consistent take-up across shots and integrated safety features like drop safeties to prevent inertial firing.[102] Double-action-only (DAO) variants eliminate SA mode for uniformity, as in some snub-nose revolvers, prioritizing safety in concealed carry by avoiding exposed hammers.[103] Trigger pull weights typically range from 2-5 pounds (0.9-2.3 kg) for SA precision rifles to 8-12 pounds (3.6-5.4 kg) for DA handguns, influencing accuracy; lighter pulls reduce shooter-induced movement but demand disciplined handling to avoid negligent discharge.[104] Break-action firearms, such as double-barreled shotguns, often pair simple SA triggers with exposed hammers or internal mechanisms, hinging open for manual reloading after each pair of shots.[99]Ammunition and Propellants

A modern firearm cartridge consists of four primary components: the casing, which encases and aligns the other elements, typically made of brass for its malleability, corrosion resistance, and ability to expand and seal the chamber during firing; the primer, a small metal cup containing a shock-sensitive primary explosive such as lead styphnate or non-toxic alternatives like diazodinitrophenol that ignites upon impact from the firing pin; the propellant charge, which generates high-pressure gas upon combustion to propel the projectile; and the projectile itself, often termed the bullet, which may be lead, jacketed copper, or specialized alloys designed for expansion, penetration, or reduced ricochet.[105][106][107] Historically, the propellant in cartridges was black powder, a low explosive formulated as a granular mixture of approximately 75% potassium nitrate (as the oxidizer), 15% charcoal (fuel), and 10% sulfur (to lower ignition temperature and aid combustion), which burns relatively slowly to produce significant smoke, residue, and fouling that corroded barrels and obscured vision in combat.[108][109] Black powder's energy density limited projectile velocities to 1,200–1,500 feet per second (fps) in typical rifle loads, necessitating loose powder measures or early paper/pieced cartridges prone to variability in performance.[54] The development of smokeless propellants revolutionized ammunition by providing higher energy output with minimal residue; French chemist Paul Vieille patented Poudre B in 1884, a gelatinized nitrocellulose formulation stabilized with ethers and cast into strands, marking the first viable military smokeless powder and enabling the French 8mm Lebel cartridge's adoption in 1886 with velocities exceeding 2,000 fps.[110] Subsequent innovations classified smokeless powders by base: single-base (primarily nitrocellulose, comprising over 90% of the mix with stabilizers like diphenylamine to inhibit acidic decomposition); double-base (nitrocellulose plasticized with 10–40% nitroglycerin for enhanced burn rate and energy); and triple-base (adding nitroguanidine to reduce muzzle flash and barrel erosion in large-caliber guns).[110][53][111] Smokeless powders generate 3–5 times the specific energy of black powder—approximately 4,000–5,000 joules per kilogram versus 2,700–3,000—allowing modern cartridges to achieve velocities over 3,000 fps in rifles while producing primarily gaseous combustion products, though they demand firearms with stronger steel alloys to withstand peak chamber pressures often exceeding 50,000 psi.[54][112] Incompatibility arises from these pressure differentials: using smokeless propellant in black powder-era arms risks catastrophic failure due to excessive force overwhelming thin barrels and actions, whereas black powder in smokeless designs yields underpowered, inefficient performance without structural risk.[113] Modern formulations incorporate deterrents, flash suppressants, and plasticizers tailored to burn rates—progressive, degressive, or neutral—for specific calibers, ensuring consistent ballistics across temperatures from -40°F to 140°F.[114]Types

Handguns

Handguns are firearms designed to be operated with one hand, featuring a short barrel and integrated grip for compact handling, in contrast to longer-barreled long guns.[115] They encompass two primary categories: revolvers, which utilize a revolving cylinder to index multiple cartridges for sequential firing, and pistols, which include semi-automatic models that cycle ammunition using recoil or gas energy along with single-shot and other variants.[116] This design prioritizes portability and rapid close-range deployment, with barrel lengths typically ranging from 2 to 6 inches.[117] The historical development of handguns traces to 13th-century hand cannons in China, primitive tube-like weapons ignited by hand-held flames.[118] By the 14th century, European adaptations incorporated matchlock mechanisms for self-ignition, evolving through wheellock and flintlock systems in the 16th and 17th centuries to improve reliability under cavalry and personal defense use.[21] The 19th century marked a pivotal advancement with percussion caps and metallic cartridges, enabling the first practical repeating designs; Samuel Colt's 1836 Paterson revolver introduced a reliable five-shot cylinder mechanism, revolutionizing multi-shot capability without manual reloading between discharges.[44] Semi-automatic pistols emerged later, with Hugo Borchardt's 1893 C-93 model demonstrating recoil-operated cycling from a detachable magazine, paving the way for widespread adoption in the 20th century.[119] Revolvers maintain simplicity through mechanical linkages that rotate and lock the cylinder via trigger pull, often in double-action mode for cocking and releasing the hammer without manual intervention, though they generally hold 5 to 8 rounds and require time-consuming reloads by extracting spent cases individually or via speedloaders.[120] Semi-automatic pistols, conversely, employ a slide to eject casings and chamber fresh rounds from box magazines holding 10 to 20 or more cartridges, facilitating quicker follow-up shots and reloads, albeit with potential vulnerabilities to jams from limp-wristing, debris, or underpowered ammunition.[121] Modern subtypes include striker-fired pistols like the Glock 17, which eliminate external hammers for reduced snag and consistent trigger pulls, and single-stack versus double-stack frames differentiating magazine capacity and grip width.[122] Derringers represent niche ultra-compact variants with 1-4 barrels, often break-action for loading, suited for deep concealment despite limited firepower.[123] In civilian contexts, particularly in the United States, handguns predominate for self-defense applications, with surveys showing they form a core component of private ownership where 68% of handgun possessors also maintain rifles or shotguns, reflecting versatile utility beyond sporting arms.[124] Production and import data indicate hundreds of millions of handguns in circulation, underscoring their enduring mechanical evolution toward balancing capacity, ergonomics, and reliability amid diverse calibers from .22 LR to .45 ACP.[125]Rifles and Shotguns

Rifles are shoulder-fired firearms characterized by a rifled barrel, featuring helical grooves that impart spin to a single projectile, stabilizing its flight through gyroscopic forces for improved accuracy and effective range typically exceeding 100 yards.[126][127] The U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives defines a rifle as a weapon designed or redesigned, made or remade, and intended to be fired from the shoulder, using the energy of an explosive in a fixed cartridge to fire a single projectile through a rifled bore for each pull of the trigger.[128] Rifling originated in 15th- to 16th-century Europe, with early implementations in German-speaking regions to enhance projectile stability beyond smoothbore limitations.[129][130] Common rifle action types include bolt-action, which requires manual cycling of a bolt to chamber rounds and offers precision for hunting and target shooting; lever-action, involving a lever near the trigger guard to cycle cartridges rapidly; pump-action, using a fore-end slide for operation; and semi-automatic, which ejects spent casings and loads new ones automatically per trigger pull while firing one round per activation.[131][132] Bolt-action rifles predominate in long-range applications due to inherent accuracy from rigid lockup, while semi-automatic variants enable faster follow-up shots.[133] Shotguns differ principally in employing smoothbore barrels, lacking rifling to accommodate shotshells that disperse multiple pellets for broader patterns or fire single slugs for penetration, suited to short-range engagements under 50 yards.[134] Per ATF regulations, a shotgun is a shoulder-fired weapon using explosive energy in a fixed shotgun shell to discharge either multiple ball shot or a single projectile through a smooth bore per trigger pull.[135] This design facilitates hunting of fowl or small game, where pattern density compensates for moving targets, though rifled barrels exist for slugs to extend range via spin stabilization.[136] Shotgun actions encompass break-action configurations, such as over-under or side-by-side doubles that hinge open for loading two shells; pump-action, manually racking the fore-end to cycle; semi-automatic, gas- or recoil-operated for reduced recoil; and less common bolt- or lever-actions.[137][131] Break-actions prevail in sporting clays and upland bird hunting for simplicity and reliability, while pump-actions offer versatility and capacity in defensive or waterfowl scenarios.[138] Rifles excel in precision at distance due to rifling-induced stability, whereas shotguns prioritize pattern spread and stopping power in confined or dynamic close-quarters uses.[139][140]Automatic and Selective-Fire Weapons