Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Thread (online communication)

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2013) |

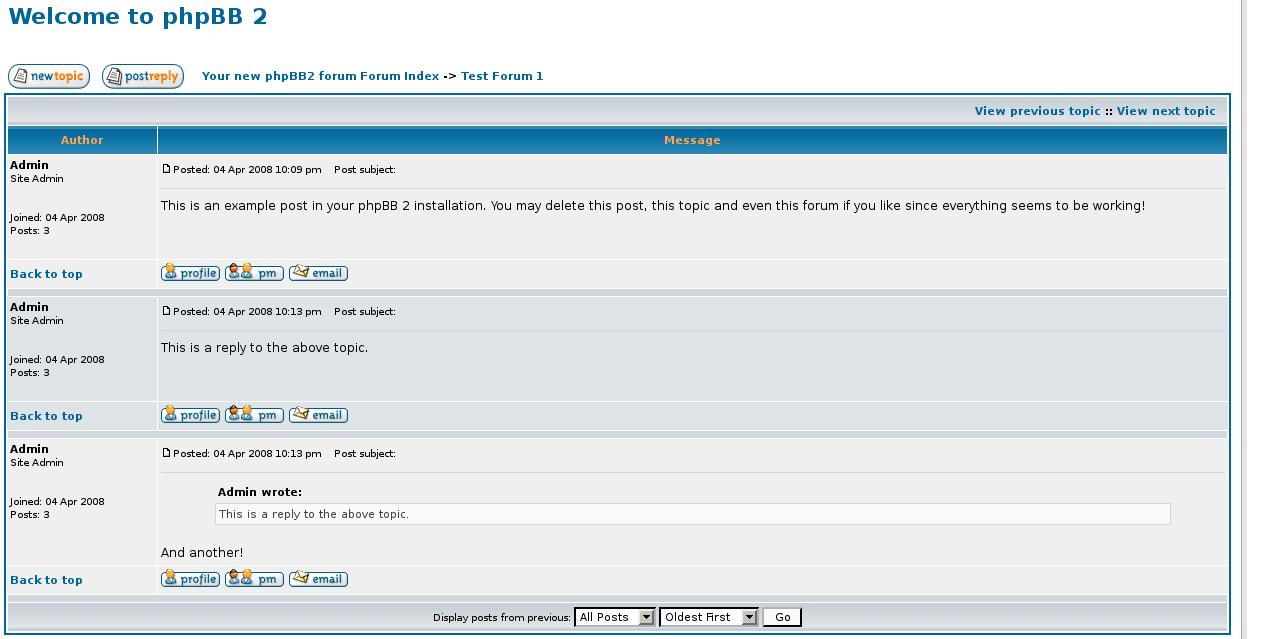

Conversation threading is a feature used by many email clients, bulletin boards, newsgroups, and Internet forums in which the software aids the user by visually grouping messages with their replies. These groups are called a conversation, topic thread, or simply a thread. A discussion forum, e-mail client or news client is said to have a "conversation view", "threaded topics" or a "threaded mode" if messages can be grouped in this manner.[1] An email thread is also sometimes called an email chain.

Threads can be displayed in a variety of ways. Early messaging systems (and most modern email clients) will automatically include original message text in a reply, making each individual email into its own copy of the entire thread. Software may also arrange threads of messages within lists, such as an email inbox. These arrangements can be hierarchical or nested, arranging messages close to their replies in a tree, or they can be linear or flat, displaying all messages in chronological order regardless of reply relationships.

Conversation threading as a form of interactive journalism became popular on Twitter from around 2016 onward, when authors such as Eric Garland and Seth Abramson began to post essays in real time, constructing them as a series of numbered tweets, each limited to 140 or 280 characters.[2]

Mechanism

[edit]Internet email clients compliant with the RFC 822 standard (and its successor RFC 5322) add a unique message identifier in the Message-ID: header field of each message, e.g.

Message-ID: <xNCx2XP2qgUc9Qd2uR99iHsiAaJfVoqj91ocj3tdWT@wikimedia.org>

If a user creates message B by replying to message A, the mail client will add the unique message ID of message A in form of the fields

In-Reply-To: <xNCx2XP2qgUc9Qd2uR99iHsiAaJfVoqj91ocj3tdWT@wikimedia.org> References: <xNCx2XP2qgUc9Qd2uR99iHsiAaJfVoqj91ocj3tdWT@wikimedia.org>

to the header of reply B. RFC 5322 defines the following algorithm for populating these fields:

The "In-Reply-To:" field will contain the contents of the "Message-ID:" field of the message to which this one is a reply (the "parent message"). If there is more than one parent message, then the "In-Reply-To:" field will contain the contents of all of the parents' "Message-ID:" fields. If there is no "Message-ID:" field in any of the parent messages, then the new message will have no "In- Reply-To:" field. The "References:" field will contain the contents of the parent's "References:" field (if any) followed by the contents of the parent's "Message-ID:" field (if any). If the parent message does not contain a "References:" field but does have an "In-Reply-To:" field containing a single message identifier, then the "References:" field will contain the contents of the parent's "In-Reply-To:" field followed by the contents of the parent's "Message-ID:" field (if any). If the parent has none of the "References:", "In-Reply-To:", or "Message-ID:" fields, then the new message will have no "References:" field.

Modern email clients then can use the unique message identifiers found in the RFC 822 Message-ID, In-Reply-To: and References: fields of all received email headers to locate the parent and root message in the hierarchy, reconstruct the chain of reply-to actions that created them, and display them as a discussion tree. The purpose of the References: field is to enable reconstruction of the discussion tree even if some replies in it are missing.

Advantages

[edit]Elimination of turn-taking and time constraints

[edit]Threaded discussions allow readers to quickly grasp the overall structure of a conversation, isolate specific points of conversations nested within the threads, and as a result, post new messages to extend discussions in any existing thread or sub-thread without time constraints. With linear threads on the other hand, once the topic shifts to a new point of discussion, users are: 1) less inclined to make posts to revisit and expand on earlier points of discussion in order to avoid fragmenting the linear conversation similar to what occurs with turn-taking in face-to-face conversations; and/or 2) obligated to make a motion to stay on topic or move to change the topic of discussion. Given this advantage, threaded discussion is most useful for facilitating extended conversations or debates [3] involving complex multi-step tasks (e.g., identify major premises → challenge veracity → share evidence → question accuracy, validity, or relevance of presented evidence) – as often found in newsgroups and complicated email chains – as opposed to simple single-step tasks (e.g., posting or share answers to a simple question).

Message targeting

[edit]Email allows messages to be targeted at particular members of the audience by using the "To" and "CC" lines. However, some message systems do not have this option. As a result, it can be difficult to determine the intended recipient of a particular message. When messages are displayed hierarchically, it is easier to visually identify the author of the previous message.

Eliminating list clutter

[edit]It can be difficult to process, analyze, evaluate, synthesize, and integrate important information when viewing large lists of messages. Grouping messages by thread makes the process of reviewing large numbers of messages in context to a given discussion topic more time efficient and with less mental effort, thus making more time and mental resources available to further extend and advance discussions within each individual topic/thread.

In group forums, allowing users to reply to threads will reduce the number of new posts shown in the list.

Some clients allow operations on entire threads of messages. For example, the text-based newsreader nn has a "kill" function which automatically deletes incoming messages based on the rules set up by the user matching the message's subject or author. This can dramatically reduce the number of messages one has to manually check and delete.

Real-time feedback

[edit]When an author, usually a journalist, posts threads via Twitter, users are able to respond to each 140- or 280-character tweet in the thread, often before the author posts the next message. This allows the author the option of including the feedback as part of subsequent messages.[2]

Disadvantages

[edit]Reliability

[edit]Accurate threading of messages requires the email software to identify messages that are replies to other messages.

Some algorithms used for this purpose can be unreliable. For example, email clients that use the subject line to relate messages can be fooled by two unrelated messages that happen to have the same subject line.[4]

Modern email clients use unique identifiers in email headers to locate the parent and root message in the hierarchy. When non-compliant clients participate in discussions, they can confuse message threading as it depends on all clients respecting these optional mail standards when composing replies to messages.[5][6]

Individual message control

[edit]Messages within a thread do not always provide the user with the same options as individual messages. For example, it may not be possible to move, star, reply to, archive, or delete individual messages that are contained within a thread.

The lack of individual message control can prevent messaging systems from being used as to-do lists (a common function of email folders). Individual messages that contain information relevant to a to-do item can easily get lost in a long thread of messages.

Parallel discussions

[edit]With conversational threading, it is much easier to reply to individual messages that are not the most recent message in the thread. As a result, multiple threads of discussions often occur in parallel. Following, revisiting, and participating in parallel discussions at the same time can be mentally challenging. Following parallel discussions can be particularly disorienting and can inhibit discussions [7] when discussion threads are not organized in a coherent, conceptual, or logical structure (e.g., threads presenting arguments in support of a given claim under debate intermingled with threads presenting arguments in opposition to the claim).

Temporal fragmentation

[edit]Thread fragmentation can be particularly problematic for systems that allow users to choose different display modes (hierarchical vs. linear). Users of the hierarchical display mode will reply to older messages, confusing users of the linear display mode.

Examples

[edit]The following email clients, forums, bbs, newsgroups, image/text boards, and social networks can group and display messages by thread.

Client-based

[edit]- Apple Mail

- Emacs Gnus

- FastMail

- Forte Agent

- Gmail

- Mailbird

- Microsoft Outlook

- Mozilla Thunderbird

- Mutt

- Pan

- Protonmail

- slrn

Web-based

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hines, Elise (5 May 2017). "What Is an Email Thread?". Lifewire. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ a b Heffernan, Virginia. "The Rise of the Twitter Thread". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ Jeong, Allan (2005). "The combined effects of response time and message content on growth patterns of discussion threads in computer-supported collaborative argumentation". International Journal of e-Learning & Distance Education. 19 (1).

- ^ Bienvenu, David. "Mail with strict threading like news". Bugzilla. Mozilla. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ Resnick, Peter W. (October 2008). "Internet Message Format". IETF Tools. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Klyne, Graham; Palme, Jacob (March 2005). "Registration of Mail and MIME Header Fields". IETF Tools. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Brooks, D.; Jeong, A. (2006). "Brooks, C. D., & Jeong, A. (2006). Effects of pre-structuring discussion threads on group interaction and group performance in computer-supported collaborative argumentation". Distance Education. 27 (3): 371–390. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.523.6207. doi:10.1080/01587910600940448. S2CID 58905596.

Sources

[edit]- Horton, Sarah (2000). Web teaching guide: A practical approach to creating course web sites. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300087277. cited in "Taking discussion online". dartmouth.edu. 2001. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010.

- Wolsey, T. DeVere, "Literature discussion in cyberspace: Young adolescents using threaded discussion groups to talk about books. Reading Online, 7(4), January/February 2004. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- Network Working Group, IETF (June 2008). "Internet Message Access Protocol - SORT and THREAD Extensions". Retrieved 2009-10-10.

Thread (online communication)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Characteristics

A thread in online communication refers to a series of interconnected messages or posts that form a cohesive conversation centered on a specific topic, typically organized either chronologically or in a hierarchical structure to reflect the flow of replies and responses.[4] This format facilitates asynchronous participation, where users contribute at their own pace without requiring real-time interaction.[5] Threads originated in early distributed systems but have become a staple in modern forums, social media, and email clients.[6] Key characteristics of threads include their sequential structure, which allows replies to nest under parent messages, creating a branched or tree-like organization that preserves the context of the discussion.[7] This nesting is often visually represented through indentation or collapsible sections, making it easier to trace conversational paths.[8] Additionally, threads exhibit persistence, meaning the entire conversation remains archived and accessible over time, supporting reflection, review, and entry by new participants at any point.[5] They also commonly support multimedia attachments, such as images, videos, or documents, as well as quoting mechanisms that enable users to reference specific parts of prior messages for clarity and continuity.[5] Unlike linear messaging systems, such as traditional SMS or flat chat logs, where messages appear in a simple chronological sequence without branching, threads enable hierarchical replies that allow multiple sub-conversations to develop from a single root message.[9] This distinction promotes deeper, more organized exchanges by maintaining relationships between responses, rather than treating all contributions as a uniform stream.[9] For example, a basic thread structure might begin with a root post posing a question, followed by two direct replies addressing different aspects of it; one of those replies could then spawn a sub-reply, forming a simple tree:- Root Post: Initial question or statement.

- Reply 1: Response to root, with agreement and elaboration.

- Sub-Reply: Further comment on Reply 1, adding new details.

- Reply 2: Alternative perspective on root, introducing counterpoints.

- Reply 1: Response to root, with agreement and elaboration.