Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Instant messaging

View on Wikipedia

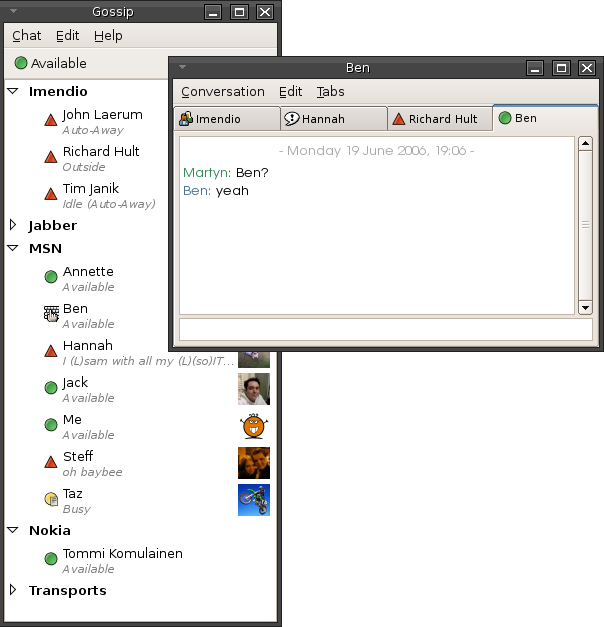

Instant messaging (IM) technology is a type of synchronous computer-mediated communication involving the immediate (real-time) transmission of messages between two or more parties over the Internet or another computer network. Originally involving simple text message exchanges, modern instant messaging applications and services (also variously known as instant messenger, messaging app, chat app, chat client, or simply a messenger) tend to also feature the exchange of multimedia, emojis, file transfer, VoIP (voice calling), and video chat capabilities.

Instant messaging systems facilitate connections between specified known users[1] (often using a contact list also known as a "buddy list" or "friend list") or in chat rooms, and can be standalone apps or integrated into a wider social media platform, or in a website where it can, for instance, be used for conversational commerce. Originally the term "instant messaging" was distinguished from "text messaging" by being run on a computer network instead of a cellular/mobile network, being able to write longer messages, real-time communication, presence ("status"), and being free (only cost of access instead of per SMS message sent).[2][3][4]

Instant messaging was pioneered in the early Internet era; the IRC protocol was the earliest to achieve wide adoption.[5] Later in the 1990s, ICQ was among the first closed and commercialized instant messengers, and several rival services appeared afterwards as it became a popular use of the Internet.[6] Beginning with its first introduction in 2005, BlackBerry Messenger became the first popular example of mobile-based IM, combining features of traditional IM and mobile SMS.[7][8] Instant messaging remains very popular today; IM apps are the most widely used smartphone apps: in 2018 for instance there were 980 million monthly active users of WeChat and 1.3 billion monthly users of WhatsApp, the largest IM network.

Overview

[edit]Instant messaging (IM), sometimes also called "messaging" or "texting", consists of computer-based human communication between two users (private messaging) or more (chat room or "group") in real-time, allowing immediate receipt of acknowledgment or reply. This is in direct contrast to email, where conversations are not in real-time, and the perceived quasi-synchrony of the communications by the users[9] (although many systems allow users to send offline messages that the other user receives when logging in).

Earlier IM networks were limited to text-based communication, not dissimilar to mobile text messaging. As technology has moved forward, IM has expanded to include voice calling using a microphone, videotelephony using webcams, file transfer,[10] location sharing, image and video transfer, voice notes, and other features.[8]

IM is conducted over the Internet or other types of networks (see also LAN messenger).[11] Depending on the IM protocol, the technical architecture can be peer-to-peer (direct point-to-point transmission) or client–server (when all clients have to first connect to the central server). Primary IM services are controlled by their corresponding companies and usually follow the client-server model.[12]

At one point, the term "Instant Messenger" was a service mark of AOL Time Warner and could not be used in software not affiliated with AOL in the United States.[13] For this reason, in April 2007, the instant messaging client formerly named Gaim (or gaim) announced that they would be renamed "Pidgin".[14]

Clients

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

Modern IM services generally provide their own client, either a separately installed application or a browser-based client. They are normally centralised networks run by the servers of the platform's operators, unlike peer-to-peer protocols like XMPP. These usually only work within the same IM network, although some allow limited function with other services (see #Interoperability). Third-party client software applications exist that will connect with most of the major IM services. There is the class of instant messengers that uses the serverless model, which doesn't require servers, and the IM network consists only of clients. There are several serverless messengers: RetroShare, Tox, Bitmessage, Ricochet, Ring. See also: LAN messenger.

Some examples of popular IM services today include Signal, Telegram, WhatsApp Messenger, WeChat, QQ Messenger, Viber, Line, and Snapchat.[citation needed] The popularity of certain apps greatly differ between different countries. Certain apps have an emphasis on certain uses - for example, Skype focuses on video calling, Slack focuses on messaging and file sharing for work teams, and Snapchat focuses on image messages. Some social networking services offer messaging services as a component of their overall platform, such as Facebook's Facebook Messenger, who also own WhatsApp. Others have a direct IM function as an additional adjunct component of their social networking platforms, like Instagram, Reddit, Tumblr, TikTok, Clubhouse and Twitter; this also includes for example dating websites, such as OkCupid or Plenty of Fish, and online gaming chat platforms.

Features

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

Private and group messaging

[edit]Private chat allows users to converse privately with another person or a group. Privacy can also be enhanced in several ways, such as end-to-end encryption by default. Public and group chat features allow users to communicate with multiple people simultaneously.

Calling

[edit]Many major IM services and applications offer a call feature for user-to-user voice calls, conference calls, and voice messages. The call functionality is useful for professionals who utilize the application for work purposes and as a hands-free method. Videotelephony using a webcam is also possible by some.

Games and entertainment

[edit]Some IM applications include in-app games for entertainment. Yahoo! Messenger, for example, introduced these where users could play a game and viewed by friends in real-time.[15] MSN Messenger featured a number of playable games within the interface. Facebook's Messenger has had a built-in option to play games with people in a chat, including games like Tetris and Blackjack.[16] Discord features multiple games built inside the "activities" tab in voice channels.[17]

Payments

[edit]A relatively new feature to instant messaging, peer-to-peer payments are available for financial tasks on top of communication. The lack of a service fee also makes these advantageous to financial applications. IM services such as Facebook Messenger[18] and the WeChat[19] 'super-app' for example offer a payment feature.

History

[edit]| 1988 | Internet Relay Chat |

|---|---|

| 1989–1995 | |

| 1996 | ICQ |

| 1997 | AIM |

| 1998 | Yahoo! Messenger |

| 1999 | XMPP MSN Messenger |

| 2000–2002 | |

| 2003 | Xfire |

| 2004–2008 | |

| 2009 | |

| 2010 | Kik Messenger |

| 2011 | Facebook Messenger Snapchat |

| 2012 | |

| 2013 | Telegram |

| 2014 | Signal |

| 2015 | Discord |

| 2016 | Riot.im/Element |

Early systems

[edit]

Though the term dates from the 1990s, instant messaging predates the Internet, first appearing on multi-user operating systems like Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS) and Multiplexed Information and Computing Service (Multics)[20][21] in the mid-1960s. Initially, some of these systems were used as notification systems for services like printing, but quickly were used to facilitate communication with other users logged into the same machine. CTSS facilitated communication via text message for up to 30 people.[22]

Parallel to instant messaging were early online chat facilities, the earliest of which was Talkomatic (1973) on the PLATO system, which allowed 5 people to chat simultaneously on a 512 x 512 plasma display (5 lines of text + 1 status line per person). During the bulletin board system (BBS) phenomenon that peaked during the 1980s, some systems incorporated chat features which were similar to instant messaging; Freelancin' Roundtable was one prime example. The first[23] such general-availability commercial online chat service (as opposed to PLATO, which was educational) was the CompuServe CB Simulator in 1980,[24] created by CompuServe executive Alexander "Sandy" Trevor in Columbus, Ohio.

As networks developed, the protocols spread with the networks. Some of these used a peer-to-peer protocol (e.g. talk, ntalk and ytalk), while others required peers to connect to a server (see talker and IRC). The Zephyr Notification Service (still in use at some institutions) was invented at MIT's Project Athena in the 1980s to allow service providers to locate and send messages to users.

Early instant messaging programs were primarily real-time text, where characters appeared as they were typed. This includes the Unix "talk" command line program, which was popular in the 1980s and early 1990s. Some BBS chat programs (i.e. Celerity BBS) also used a similar interface. Modern implementations of real-time text also exist in instant messengers, such as AOL's Real-Time IM[25] as an optional feature.[26]

In the latter half of the 1980s and into the early 1990s, the Quantum Link online service for Commodore 64 computers offered user-to-user messages between concurrently connected customers, which they called "On-Line Messages" (or OLM for short), and later "FlashMail." Quantum Link later became America Online and made AOL Instant Messenger (AIM, discussed later). While the Quantum Link client software ran on a Commodore 64, using only the Commodore's PETSCII text-graphics, the screen was visually divided into sections and OLMs would appear as a yellow bar saying "Message From:" and the name of the sender along with the message across the top of whatever the user was already doing, and presented a list of options for responding.[27] As such, it could be considered a type of graphical user interface (GUI), albeit much more primitive than the later Unix, Windows and Macintosh based GUI IM software. OLMs were what Q-Link called "Plus Services" meaning they charged an extra per-minute fee on top of the monthly Q-Link access costs.

Development of the Internet Relay Chat (IRC) protocol began in 1989, and this would become the Internet's first widespread instant messaging standard.[28]

Graphical messengers

[edit]

Modern, Internet-wide, GUI-based messaging clients as they are known today, began to take off in the mid-1990s with PowWow, ICQ, and AOL Instant Messenger (AIM). Similar functionality was offered by CU-SeeMe in 1992; though primarily an audio/video chat link, users could also send textual messages to each other. AOL later acquired Mirabilis, the authors of ICQ; establishing dominance in the instant messaging market.[22] A few years later ICQ (then owned by AOL) was awarded two patents for instant messaging by the U.S. patent office. Meanwhile, other companies developed their own software; (Excite, Microsoft (MSN), Ubique, and Yahoo!), each with its own proprietary protocol and client; users therefore had to run multiple client applications if they wished to use more than one of these networks. However, the open protocol IRC continued to be popular by the millennium, and its most popular graphical app was mIRC.[28]

While instant messaging was mainly in use for consumer recreational purposes, in 1998, IBM launched their Lotus Sametime instant messenger software, the first popular example of enterprise-grade instant messaging.[29] In 2000, an open-source application and open standards-based protocol called Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP) was launched, initially branded as Jabber. XMPP servers could act as gateways to other IM protocols, reducing the need to run multiple clients.[30]

Video calling using a webcam also started taking off during this time. Microsoft's NetMeeting, which was focused on business "web conferencing", was one of the earliest; the company then launched Windows Messenger, coming preloaded on Windows XP, featuring video capabilities.[31] Yahoo! Messenger added video capabilities in 2001;[32] by 2005, such features were built-in also in AIM, MSN Messenger, and Skype.[33]

There were a reported 100 million users of instant messaging in 2001.[34] As of 2003, AIM was the globally most popular instant messenger with 195 million users and exchanges of 1.6 billion messages daily.[2] By 2006, AIM controlled 52 percent of the instant messaging market, but rapidly declined shortly thereafter as the company struggled to compete with other services.[22]

Integrated IM and mobile

[edit]

Instant messaging integrated in other services started picking up pace in the late 2000s. Myspace, the then-largest social networking service, launched Myspace IM in 2006, shortly after Google's Gtalk, which was integrated into its Gmail webmail interface. Facebook Chat launched in 2008, providing IM to users of the social network.[35] By 2010, traditional instant messaging was in sharp decline in favor of these new messaging features on wider social networks, which at the time were not normally called IM.[36] For instance, AIM's userbase had declined by more than half throughout the year 2011.[37]

Standalone instant messenger services were revived, evolving into becoming primarily being used on mobile due to the increasing use of Internet-enabled cell phones and smartphones. Often called "chat apps", to distinguish it from cellular-based SMS and MMS "texting" services, these newer services were specially designed to be run on mobile platforms, as opposed to older services like AIM and MSN; BlackBerry Messenger, released in 2005, was one of the influential pioneers of mobile IM,[7] and led to other companies launching services with proprietary protocols, such as WhatsApp.[22] Mobile instant messaging surpassed SMS in global message volume by 2013.[22][38] While SMS relied on traditional paid telephone services, IM apps on mobile were available for free or a minor data charge.[39][40]

Older IM services were eventually shut, including AIM[41] and Yahoo! Messenger, and also Windows Live Messenger, which merged into Skype in 2013. In 2014, it was reported that instant messaging had more users than social networks.[42] Concurrently, rising use of instant messaging at workplaces led to the creation of new services (enterprise application integration (EAI)) often integrated with other enterprise applications such as workflow systems, for example in Skype for Business, Slack and Microsoft Teams.[43] Meanwhile, the launch of Discord in 2015 has marked a notable new example of traditional IM originally designed for desktops.[44]

Interoperability

[edit]

Most IM protocols are proprietary and are not designed to be interoperable with others, meaning that many IM networks have been incompatible and users have been unable to reach users on other networks.[45] As of 2024, fragmentation of IM services means that a typical user is likely to have to use more networks than ever, including the need to download the apps and signing up, to stay in touch with all their contacts.[46] However, there had been attempts for solutions.[8]

Multi-protocol clients can use any of the IM protocols by using additional local libraries for each protocol. Examples of multi-protocol instant messenger software include Pidgin and Trillian,[8] and more recently Beeper. These third-party clients have often been unable to keep up due to proprietary protocol restrictions and getting locked out of it.[8] For instance, in 2015, WhatsApp started banning users who were using unofficial clients.[47] Major IM providers usually cite the need for formal agreements, and security concerns as reasons for making changes.

Attempted open standards

[edit]There have been several attempts in the past to create a unified standard for instant messaging, including:

- IETF's Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) and SIP for Instant Messaging and Presence Leveraging Extensions (SIMPLE)

- Application Exchange (APEX),

- Instant Messaging and Presence Protocol (IMPP),

- Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP), based on XML, and

- Open Mobile Alliance's Instant Messaging and Presence Service (IMPS), developed specifically for mobile devices.

History and agreements

[edit]Critics say AOL's slowness in embracing interoperability has caused setbacks to other companies trying to grow their businesses. AOL has said it supports the development of an interoperable system for all IM networks but has cited privacy and security concerns as the reasons it's taking its time. Competitors have labeled that argument a "smoke screen."

In the early 2000s, when instant messaging was quickly growing, most attempts at producing a unified standard for the-then major IM providers (AOL, Yahoo!, Microsoft) had failed. There was a "bitter row" between AOL and its rivals regarding the opening up of their networks.[50] In 2000, U.S. regulatory Federal Communications Commission (FCC) proposed, and supported by Microsoft chairman Bill Gates, that AOL providing interoperability of its AIM and ICQ instant messengers with Microsoft's MSN Messenger was a condition for the forthcoming AOL-Time Warner merger.[51]

However, in 2004, Microsoft, Yahoo! and AOL agreed to a deal in which Microsoft's enterprise IM server Live Communications Server 2005 would have the possibility to talk to their rival counterparts and vice versa.[52] On October 13, 2005, Microsoft and Yahoo! announced that their IM networks would soon be interoperable, using SIP/SIMPLE. This was finally rolled out to Windows Live Messenger and Yahoo! Messenger users in July 2006.[53] Additionally, in December 2005 by the AOL and Google strategic partnership deal, it was announced that AIM and ICQ users would be able to communicate with Google Talk users.[54] However this feature took until December 2007 to roll out.[55] XMPP provided the best example of open protocol interoperability, having had gateways that connected to Google Talk, Lotus Sametime and others.[56]

Later, RCS was developed by telecommunication companies as an instant messaging protocol to replace SMS under a unified standard. In 2022, the European Union passed the Digital Markets Act, which largely came into effect in early 2023. Among other things, the legislation mandates certain interoperability between the largest IM platforms in use in Europe.[57] As a result, in March 2024, Meta Platforms opened up its WhatsApp and Messenger networks to be interoperable.[58]

Technical

[edit]There are two ways to combine the many disparate protocols:

- Combine the many disparate protocols inside the IM client application.

- Combine the many disparate protocols inside the IM server application. This approach moves the task of communicating with the other services to the server. Clients need not know or care about other IM protocols. For example, LCS 2005 Public IM Connectivity. This approach is popular in XMPP servers; however, the so-called transport projects suffer the same reverse engineering difficulties as any other project involved with closed protocols or formats.

Some approaches allow organizations to deploy their own, private instant messaging network by enabling them to restrict access to the server (often with the IM network entirely behind their firewall) and administer user permissions. Other corporate messaging systems allow registered users to also connect from outside the corporation LAN, by using an encrypted, firewall-friendly, HTTPS-based protocol. Usually, a dedicated corporate IM server has several advantages, such as pre-populated contact lists, integrated authentication, and better security and privacy.[citation needed]

Effects of IM on communication

[edit]Workplace communication

[edit]Instant messaging has changed how people communicate in the workplace. Enterprise messaging applications like Slack, Symphony, Teamnote and Yammer allow companies to enforce policies on how employees message at work and ensure secure storage of sensitive data.[59] They allow employees to separate work information from their personal emails and texts.

Messaging applications may make workplace communication efficient, but they can also have consequences on productivity. A study at Slack showed on average, people spend 10 hours a day on Slack, which is about 67% more time than they spend using email.[60]

Instant messaging is implemented in many video-conferencing tools. A study of chat use during work-related videoconferencing found that chat during meetings allows participants to communicate without interrupting the meeting, plan action around common resources, and enables greater inclusion.[61] The study also found that chat can cause distractions and information asymmetries between participants.

Language

[edit]

Users sometimes make use of internet slang or text speak to abbreviate common words or expressions to quicken conversations or reduce keystrokes. The language has become widespread, with well-known expressions such as 'lol' translated over to face-to-face language.

Emotions are often expressed in shorthand, such as the abbreviation LOL, BRB and TTYL; respectively laugh(ing) out loud, be right back, and talk to you later. Some, however, attempt to be more accurate with emotional expression over IM. Real time reactions such as (chortle) (snort) (guffaw) or (eye-roll) have been popular at one point. Also there are certain standards that are being introduced into mainstream conversations including, '#' indicates the use of sarcasm in a statement and '*' which indicates a spelling mistake and/or grammatical error in the prior message, followed by a correction.[62]

Business application

[edit]Instant messaging products can usually be categorised into two types: Enterprise Instant Messaging (EIM)[63] and Consumer Instant Messaging (CIM).[64] Enterprise solutions use an internal IM server, however this is not always feasible, particularly for smaller businesses with limited budgets. The second option, using a CIM provides the advantage of being inexpensive to implement and has little need for investing in new hardware or server software. IM is increasingly becoming a feature of enterprise software rather than a stand-alone application.[citation needed]

Instant messaging has proven to be similar to personal computers, email, and the World Wide Web, in that its adoption for use as a business communications medium was driven primarily by individual employees using consumer software at work, rather than by formal mandate or provisioning by corporate information technology departments. Tens of millions of the consumer IM accounts in use are being used for business purposes by employees of companies and other organizations. The adoption of IM across corporate networks outside of the control of IT organizations creates risks and liabilities for companies who do not effectively manage and support IM use.[citation needed] IM was initially shunned by the corporate world partly due to security concerns, but by 2003 many had started embracing these new services.[65]

Software

[edit]In response to the demand for business-grade IM and the need to ensure security and legal compliance, a new type of instant messaging, called "Enterprise Instant Messaging" ("EIM") was created when Lotus Software launched IBM Lotus Sametime in 1998. Microsoft followed suit shortly thereafter with Microsoft Exchange Instant Messaging, later created a new platform called Microsoft Office Live Communications Server, and released Office Communications Server 2007 in October 2007. Oracle Corporation also jumped into the market with its Oracle Beehive unified collaboration software.[66]

Both IBM Lotus and Microsoft have introduced federation between their EIM systems and some of the public IM networks so that employees may use one interface to both their internal EIM system and their contacts on AOL, MSN, and Yahoo. As of 2010, leading EIM platforms include IBM Lotus Sametime, Microsoft Office Communications Server, Jabber XCP and Cisco Unified Presence.[independent source needed] Industry-focused EIM platforms such as Reuters Messaging and Bloomberg Messaging also provide IM abilities to financial services companies.[independent source needed]

Security and archiving

[edit]Crackers (malicious or black hat hackers) have consistently used IM networks as vectors for delivering phishing attempts, drive-by URLs, and virus-laden file attachments, with over 1100 discrete attacks listed by the IM Security Center[67] in 2004–2007. Hackers use two methods of delivering malicious code through IM: delivery of viruses, trojan horses, or spyware within an infected file, and the use of "socially engineered" text with a web address that entices the recipient to click on a URL connecting him or her to a website that then downloads malicious code.[citation needed]

IM connections sometimes occur in plain text, making them vulnerable to eavesdropping. Also, IM client software often requires the user to expose open UDP ports to the world, raising the threat posed by potential security vulnerabilities.[68]

In the early 2000s, a new class of IT security providers emerged to provide remedies for the risks and liabilities faced by corporations who chose to use IM for business communications. The IM security providers created new products to be installed in corporate networks for the purpose of archiving, content-scanning, and security-scanning IM traffic moving in and out of the corporation. Similar to the e-mail filtering vendors, the IM security providers focus on the risks and liabilities described above.[69][70][71]

With the rapid adoption of IM in the workplace, demand for IM security products began to grow in the mid-2000s. By 2007, the preferred platform for the purchase of security software had become the "computer appliance", according to IDC, who estimated that by 2008, 80% of network security products would be delivered via an appliance.[72]

By 2014, however, instant messengers' safety level was still extremely poor. According to a scorecard by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, only 7 out of 39 instant messengers received a perfect score. In contrast, the most popular instant messengers at the time only attained a score of 2 out of 7.[73][74] A number of studies have shown that IM services are quite vulnerable for providing user privacy.[75][76]

In 2023, cybersecurity researchers discovered that numerous malicious "mods" exist of the Telegram instant messenger, which is freely available for download from Google Play.[77]

Message history

[edit]Instant messages are often logged in a local message history, similar to emails' persistent nature. IM networks may store messages with either local-based device storage (e.g. WhatsApp, Viber, Line, WeChat, Signal etc. software) or cloud-based server storage provided by the service (e.g. Telegram, Skype, Facebook Messenger, Google Meet/Chat, Discord, Slack etc.). Although cloud-based storage is advertised to offer encrypted messages, it poses an increased risk that the IM provider may have access to the decryption keys and view the user's saved messages.[78]

This requires users to trust IM servers and providers because messages can generally be accessed by the company. Companies may be compelled to reveal their user's communication and suspend user accounts for any reason.[79]

Tracking and spying

[edit]News reports from 2013 revealed that the NSA is not only collecting emails and IM messages but also tracking relationships between senders and receivers of those chats and emails in a process known as metadata collection.[80] Metadata refers to the data concerned about the chat or email as opposed to contents of messages. It may be used to collect valuable information.[81]

In January 2014, Matthew Campbell and Michael Hurley filed a class-action lawsuit against Facebook for breaching the Electronic Communications Privacy Act.[82] They alleged that the information in their supposedly private messages was being read and used to generate profit, specifically "for purposes including but not limited to data mining and user profiling".

In corporate use of IM, organizational offerings have become very sophisticated in their security and logging measures. An employee or organization member must be granted login credentials and permission to use the messaging system. Creating a specific account for each user allows the organization to identify, track and record all use of their messenger system on their servers.[83]

Encryption

[edit]Encryption is the primary method that instant messaging apps use to protect user's data privacy and security. For corporate use, encryption and conversation archiving are usually regarded as important features due to security concerns.[84] There are also a bunch of open source encrypting messengers.[85]

IM does hold potential advantages over SMS. SMS messages are not encrypted, making them insecure, as the content of each SMS message is visible to mobile carriers and governments and can be intercepted by a third party,[86] may leak metadata (such as phone numbers),[86] or be spoofed and the sender of the message can be edited to impersonate another person.[86]

Current instant messaging networks that use end-to-end encryption include Signal,[87][88] WhatsApp, Wire and iMessage.[86][89][90] Signal and iMessage have started using Post-quantum cryptography in September 2023[91][92][93] and April 2024[94][95][96] respectively. Applications that have been criticized for lacking or poor encryption methods include Telegram and Confide, as both are prone to error or not having encryption enabled by default.[86][97]

Compliance risks

[edit]In addition to the malicious code threat, using instant messaging at work creates a risk of non-compliance with laws and regulations governing electronic communications in businesses. In the United States alone, there are over 10,000 laws and regulations related to electronic messaging and records retention.[98] The better-known of these include the Sarbanes–Oxley Act, HIPAA, and SEC 17a-3.

Clarification from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) was issued to member firms in the financial services industry in December 2007, noting that "electronic communications", "email", and "electronic correspondence" may be used interchangeably and can include such forms of electronic messaging as instant messaging and text messaging.[99] Changes to Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, effective December 1, 2006, created a new category for electronic records which may be requested during discovery in legal proceedings.[citation needed]

Most nations also regulate electronic messaging and records retention similarly to the United States. The most common regulations related to IM at work involve producing archived business communications to satisfy government or judicial requests under law. Many instant messaging communications fall into the category of business communications that must be archived and retrievable.[citation needed]

Current user base

[edit]As of May 2025, the most used instant messaging apps and services worldwide include: Signal with 100 million, Line with 197 million, Viber with 260 million, QQ with 562 million, Snapchat with 900 million, Telegram with 1 billion, Facebook Messenger with 1.3 billion, WeChat with 1.39 billion, and WhatsApp with 3 billion users.[100][101]

There are 25 countries in the world where WhatsApp messenger is not the market leader in IM, such as the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Philippines, and China.[100][102]

IM apps have varying levels of adoption in different countries. As of April 2022:[103][104]

- WhatsApp by Meta Platforms is the most popular instant messaging network in several countries in South America, Western Europe, Africa, Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.

- Facebook Messenger by Meta Platforms is the most popular instant messaging network in North America, Northern Europe, some Central Europe countries, and Oceania.

- Telegram is the most popular instant messaging app in several Eastern Europe countries, and the second preferred option after WhatsApp in several countries in Western Europe, Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, Central and South America.

- Viber by Rakuten has a strong presence in Central and Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, Ukraine, Russia). It is also moderately successful in Philippines and Vietnam.[105][106][107]

- Line by Naver Corporation is used widely in some countries in Asia (Japan, Taiwan, Thailand).

- Instant messaging apps and services that are predominately used in only one country include: KakaoTalk in South Korea, Zalo in Vietnam, WeChat in China, and imo in Qatar.

- While not the dominant app for one-to-one messaging in any country, Discord is commonly used among online communities due to its ability to support chats with a large amount of members, topic-based channels, and cloud-based storage. Signal, favoured for its privacy-focused approach, is among the top three preferred option in the Netherlands, Sweden, and Finland.[103]

See also

[edit]Terms

[edit]- Ambient awareness – Term used to describe a form of peripheral social awareness

- Communication protocol – System for exchanging messages between computing systems

- Mass collaboration – Many people working on a single project

- Message-oriented middleware – Type of software or hardware infrastructure

- Operator messaging – Messaging answer service

- Social media – Virtual online communities

- Text messaging – Act of typing and sending a brief, digital message

- SMS – Text messaging service component

- Unified communications – Business and marketing concept / Messaging

Lists

[edit]- Comparison of cross-platform instant messaging clients

- Comparison of instant messaging protocols

- Comparison of user features of messaging platforms

Other

[edit]- Code Shikara – Family of malware worms that spreads through instant messaging

- Meatspace Chat

References

[edit]- ^ "What is Instant Messaging? - Definition from SearchUnifiedCommunications". Unified Communications. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ a b "Will instant messaging be the new texting?". 2003-06-30. Retrieved 2024-08-05.

- ^ "MMS-multi media messaging and MMS-interconnection". Electronic Communications Committee (ECC). 2004.

- ^ Foderaro, Lisa W. (2005-01-09). "Young Cell Users Rack Up Debt, a Message at a Time". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-08-05.

- ^ "History of IRC". 4 January 2021. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "The Evolution of Instant Messaging". 17 November 2016.

- ^ a b "How BlackBerry Messenger Forever Changed the Way We Text". Inverse. 2023-05-09. Retrieved 2024-08-05.

- ^ a b c d e "RIP, ICQ: Why all instant messaging disappears (in the end)". ZDNET. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "8 Examples of Instant Messaging | ezTalks". www.eztalks.com. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- ^ Clifford, Catherine (2013-12-11). "Top 10 Apps for Instant Messaging (Infographic)". Entrepreneur. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- ^ "Part 1. Introduction: The basics of instant messaging". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2004-09-01. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ^ "How Instant Messaging Works". HowStuffWorks. 2001-03-28. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ^ "Summary of Final Decisions Issued by the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ "Important and Long Delayed News". April 6, 2007. Archived from the original on April 8, 2007.

- ^ "Yahoo! Messenger Launches "Imvironments™" with Next Generation of Yahoo! Messenger Service | Altaba Inc".

- ^ "How to play ALL of Facebook Messenger's new games". Digital Spy. 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Discord Activities: Play Games and Watch Together". discord.com. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ vincithevin (2024-08-02). "Beijing Visitor's Guide: A Guide to Payment Services in the Capital". www.thebeijinger.com. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ Fetter, Mirko (2019). New Concepts for Presence and Availability in Ubiquitous and Mobile Computing. University of Bamberg Press. p. 38. ISBN 9783863096236.

The basic concept of sending instantaneously messages to logged in users came with ... CTSS ...

- ^ Tom Van Vleck. "Instant Messaging on CTSS and Multics". Multicians.org. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ a b c d e "A Brief History of Chat Apps · Guide to Chat Apps". towcenter.gitbooks.io. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- ^ CompuServe Innovator Resigns After 25 Years, The Columbus Dispatch, May 11, 1996, p. 2F

- ^ Wired and Inspired, The Columbus Dispatch (Business page), by Mike Pramik, November 12, 2000

- ^ "AOL Instant Messenger's Real-Time IM feature". Help.aol.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ "RealJabber.org's animation of real-time text". Realjabber.org. Archived from the original on 2013-10-26. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ "Screenshot of a Quantum Link OLM". Archived from the original on June 19, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ a b Andrei, Mihai (2018-11-09). "The Internet Relay Chat (IRC) turned 30 -- and it probably changed our lives". ZME Science. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ Tay, Liz (2008-07-08). "IBM touts unification of consumer and business communication tools". iTnews. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "XMPP". xmpp.org. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "New Yahoo IM chats up broadband". CNET. 2002-08-15. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Yahoo! Messenger offers video option - Jun. 26, 2001". money.cnn.com. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Skype adds in video to net calls". 2005-12-01. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Messaging in an instant". 2001-09-09. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ Bergfeld, Carlos (2008-04-17). "Facebook Chat: Reports of AIM's Death Greatly Exaggerated - CBS News". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 2024-08-06.[dead link]

- ^ Kelly, Jon (24 May 2010). "Instant messaging: This conversation is terminated". BBC. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Carlson, Nicholas. "In The Biggest Blown Opportunity Ever, AOL Instant Messenger Has Utterly Collapsed". Business Insider. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Chat apps surpass SMS for the first time, study finds". 29 April 2013.

- ^ Ling, Rich; Lai, Chih-Hui (2016-10-01). "Microcoordination 2.0: Social Coordination in the Age of Smartphones and Messaging Apps". Journal of Communication. 66 (5): 834–856. doi:10.1111/jcom.12251. ISSN 0021-9916.

- ^ Horwitz, Josh (25 August 2015). "Why WhatsApp bombed in the US, while Snapchat and Kik blew up". Quartz. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ "AIM has been discontinued as of December 15, 2017". help.aol.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017.

- ^ "The rise of messaging platforms". The Economist, via Chatbot News Daily. 2017-01-22. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Business Use of Instant Messaging on the Rise, Email Still Primary Survey Finds". 2017-06-09. Archived from the original on 2024-08-06. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Third-party Discord app brings back MSN Messenger but there's a catch". Dexerto. 2024-04-05. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "A Brief History of Chat Services" (PDF). sameroom.io. 19 April 2023.

- ^ "The best all-in-one messaging apps in 2024". zapier.com. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "WhatsApp Permanently Bans Users of Unofficial Clients".

- ^ "AOL, Time Warner complete merger with FCC blessing". CNET.

- ^ "Green light for AOL-Time Warner merger". ZDNET.

- ^ "AOL wins instant messaging case". 2002-12-19. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Gates Adds His Voice To Instant Messaging". Forbes. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ Hicks, Matthew (2004-07-15). "Microsoft Opens IM Server to AOL, Yahoo". eWeek. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Microsoft, Yahoo connect IM services". CNET. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ Bylund, Anders (2005-12-21). "Google buys 5 percent of AOL; Google Talk and AIM to chat it up". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ Schwartz, Barry (2007-12-05). "Google Talk Meets AOL Instant Messager: Time Warner & Google Complete AIM Integration Deal". Search Engine Land. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Jabber gateway aims to link XMPP, SIMPLE". InfoWorld. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ Claburn, Thomas. "EU mandated interoperable messaging not so simple: Paper". www.theregister.com. Retrieved 2023-11-11.

- ^ Jowitt, Tom (2024-03-13). "Meta Messaging Interoperability Whatsapp, Messenger". Silicon UK. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Text Messaging Apps Are Transforming Workplace Communications". TeleMessage. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ Kashyap, Vartika. "Are Messaging Apps at Work Affecting Team Productivity?". learn.g2.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ Sarkar, Advait; Rintel, Sean; Borowiec, Damian; Bergmann, Rachel; Gillett, Sharon; Bragg, Danielle; Baym, Nancy; Sellen, Abigail (2021-05-08), "The promise and peril of parallel chat in video meetings for work", Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 1–8, doi:10.1145/3411763.3451793, ISBN 978-1-4503-8095-9, S2CID 233987188, retrieved 2021-11-01

- ^ instant messaging Archived February 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, NetworkDictionary.com.

- ^ "Better Business IMs - Business Technology". Im.about.com. 2012-04-10. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ "Reader Questions IM Privacy at Work". Im.about.com. 2008-03-15. Archived from the original on 2010-08-25. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ "Message in a bottleneck". CNET. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Oracle Buzzes with Updates for its Beehive Collaboration Platform". CMSWire. May 12, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- ^ "IM Security Center". Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ "Why just say no to IM at work". Blog.anta.net. October 29, 2009. ISSN 1797-1993. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ Evers, Joris (2005-06-06). "Akonix ships IM security appliance". ZDNET. Retrieved 2025-10-07.

- ^ "Akonix L7 Enterprise". PCMAG. 2003-11-11. Retrieved 2025-10-07.

- ^ Hu, Jim (2002-11-12). "MS corporate IM touts security, archives". ZDNET. Retrieved 2025-10-07.

- ^ Chris Christiansen and Rose Ryan, International Data Corp., "IDC Telebriefing: Threat Management Security Appliance Review and Forecast"

- ^ Dredge, Stuart (2014-11-06). "How secure is your favourite messaging app? Today's Open Thread". the Guardian. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ^ "Secure Messaging Scorecard". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ^ Saleh, Saad (2015). IM Session Identification by Outlier Detection in Cross-correlation Functions. Conference on Information Sciences and Systems (CISS). doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3524.5602.

- ^ Saleh, Saad (December 2014). Breaching IM Session Privacy Using Causality. IEEE Global Communications Conference (Globecom). doi:10.13140/2.1.1112.2244.

- ^ Baran, Guru (2023-09-11). "Weaponized Telegram App Infected Over 60K Android Users". Cyber Security News. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ Doffman, Zak. "No, Don't Quit WhatsApp To Use Telegram Instead—Here's Why". Forbes. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- ^ "Skype hauled into court after refusing to hand call records to cops". The Register. 26 May 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Risen, James; Poitras, Laura (28 September 2013). "N.S.A. Gathers Data on Social Connections of U.S. Citizens". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- ^ "A Primer on Metadata: Separating Fact from Fiction - Privacy By Design". Privacybydesign.ca. 2013-07-17. Archived from the original on 2014-02-26. Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- ^ Grove, Jennifer (2014). Facebook Sued for Allegedly Intercepting Private Messages. Mobile World Congress. Retrieved from Cnet.com

- ^ "Cisco WebEx Messenger: Enterprise Instant Messaging through a Commercial-Grade Multilayered Architecture" (PDF). Cisco.com. Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- ^ Schneier, Bruce; Seidel, Kathleen; Vijayakumar, Saranya (11 February 2016). "Multi-Encrypting Messengers – in: A Worldwide Survey of Encryption Products" (PDF). Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ Adams, David; Maier, Ann-Kathrin (6 June 2016). "Big Seven Study, open source crypto-messengers to be compared – or: Comprehensive Confidentiality Review & Audit: Encrypting E-Mail-Client & Secure Instant Messenger, Descriptions, tests and analysis reviews of 20 functions of the applications based on the essential fields and methods of evaluation of the 8 major international audit manuals for IT security investigations including 38 figures and 87 tables" (PDF). Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Cybersecurity 101: How to choose and use an encrypted messaging app". TechCrunch. 25 December 2018. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ "The Best Private Instant Messengers". Privacy Guides. Retrieved 2025-07-05.

- ^ "Communicating With Others". ssd.eff.org. Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved 2025-07-05.

- ^ "iMessage security overview". Apple Support. Retrieved 2025-07-05.

- ^ "Best WhatsApp Alternatives". Tuta. 24 February 2024. Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- ^ "Quantum Resistance and the Signal Protocol". Signal Messenger. Retrieved 2025-07-05.

- ^ Goodin, Dan (2023-09-20). "The Signal Protocol used by 1+ billion people is getting a post-quantum makeover". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2025-07-05.

- ^ "Signal adds quantum-resistant encryption to its E2EE messaging protocol". BleepingComputer. Retrieved 2025-07-05.

- ^ Goodin, Dan (2024-02-22). "iMessage gets a major makeover that puts it on equal footing with Signal". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2025-07-05.

- ^ Burgess, Matt. "Apple's iMessage Is Getting Post-Quantum Encryption". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2025-07-05.

- ^ "iMessage with PQ3: The new state of the art in quantum-secure messaging at scale". security.apple.com. Apple, Inc. 21 February 2024.

- ^ Jakobsen, Jakob; Orlandi, Claudio (2016). "On the CCA (in)security of MTProto" (PDF). Proceedings of the 6th Workshop on Security and Privacy in Smartphones and Mobile Devices. Aarhus University. p. 6. doi:10.1145/2994459.2994468. ISBN 978-1-4503-4564-4.

- ^ "ESG compliance report excerpt, Part 1: Introduction". Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ FINRA, Regulatory Notice 07-59, Supervision of Electronic Communications, December 2007

- ^ a b "Messaging App Usage Statistics Around the World". MessengerPeople. 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ "The most popular messaging apps in the world by country". Sinch. 2025-05-29.

- ^ "11 New People Join Social Media Every Second (And Other Impressive Stats)". Archived from the original on 2018-01-30.

- ^ a b "Most Popular Messaging Apps by Country". Similarweb.

- ^ "Most Popular Messaging Apps: Top Messaging Apps 2021". Respond.io.

- ^ "Viber usage spikes as pandemic strikes". The Philippine Star. 29 January 2021.

- ^ "Viber expands foothold in the Philippines in 2021". BusinessMirror. 18 December 2021.

- ^ "When chatting apps can be overwhelming". VnExpress International.

External links

[edit]Instant messaging

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Core Principles

Instant messaging (IM) constitutes the exchange of near-real-time text messages between two or more users via dedicated software applications or integrated network services, enabling synchronous communication over the internet or other digital networks.[9][10] This differs fundamentally from asynchronous email by prioritizing immediacy, where messages are delivered and acknowledged with minimal latency, often within seconds.[11] Core to IM is the integration of presence awareness, which informs users of contacts' online status, availability, and activity levels through server-mediated signals, facilitating context-aware initiation of conversations.[12][5] At its foundation, IM operates on client-server architectures or peer-to-peer models, where client applications authenticate users, establish persistent connections, and route messages via standardized or proprietary protocols.[13] The Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP), formalized as an IETF standard, exemplifies open IM principles by using XML streams for extensible, federated message exchange, presence notifications, and session management across disparate servers.[14][15] This protocol supports core functions like one-to-one chats, group messaging, and extensions for multimedia, ensuring interoperability while allowing proprietary enhancements for features such as end-to-end encryption.[6] Reliability in IM derives from transport mechanisms like TCP for ordered delivery and acknowledgments, mitigating packet loss in real-time scenarios, though early systems like IRC relied on simpler, channel-based broadcasting without inherent presence.[16] Causal realism in IM design emphasizes low-latency feedback loops—such as typing indicators and read receipts—to mimic face-to-face interaction, reducing miscommunication from delayed responses.[17] Empirical data from protocol implementations show that effective IM systems balance scalability with security; for instance, XMPP's decentralized federation prevents single-point failures but introduces complexity in trust verification compared to centralized alternatives.[18] User authentication via credentials or tokens underpins privacy, though historical vulnerabilities highlight the need for ongoing cryptographic upgrades to counter interception risks in unencrypted transmissions.[19]Underlying Technologies

Instant messaging systems predominantly employ a client-server architecture, in which end-user clients connect to servers that route messages, manage presence information, and queue undelivered messages for offline recipients. This model facilitates centralized authentication, scalability through server federation, and reliable delivery via persistent connections or polling mechanisms.[2][6] Peer-to-peer architectures, where clients communicate directly after initial server rendezvous, offer lower latency and reduced server dependency but face challenges with firewall traversal, dynamic IP handling, and consistent presence tracking, limiting their adoption in mainstream implementations.[20] At the transport layer, Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) ensures reliable, ordered packet delivery for text-based exchanges, while User Datagram Protocol (UDP) supports low-latency applications like voice or video extensions. Web-based clients leverage WebSockets for full-duplex communication over a single TCP connection, bypassing limitations of HTTP polling or long-polling techniques.[6] Application-layer protocols define message structure, routing, and features like presence stanzas. The Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP), standardized in RFC 6120 for core stream management and RFC 6121 for instant messaging and presence, employs XML-formatted streams transmitted over TCP, enabling federated interoperability across independent servers.[21][14] Other foundational protocols include Internet Relay Chat (IRC), which uses plain-text commands over TCP for multi-user channels, and SIP for Instant Messaging and Presence Leveraging Extensions (SIMPLE), building on Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) for signaling.[16][22] Proprietary systems, such as those in WhatsApp, adapt XMPP with custom binary encoding and server-side optimizations for high-scale mobile usage.[23] Security protocols layer encryption atop these foundations: Transport Layer Security (TLS) secures client-server channels against interception, while end-to-end encryption (E2EE) protects message content from server access using asymmetric cryptography and key ratcheting. In XMPP, the OMEMO extension implements E2EE via the Signal Protocol's double-ratchet algorithm, providing forward secrecy and deniability for multi-device synchronization.[24] Mobile deployments integrate push notification services, such as Apple's Push Notification service or Firebase Cloud Messaging, to deliver alerts without maintaining constant connections, thereby optimizing battery life and network efficiency.[23]Historical Development

Origins in Early Computing

The precursors to modern instant messaging emerged in early multi-user timesharing systems of the 1960s, which enabled real-time interaction among logged-in users on shared mainframe computers.[25] These systems, such as MIT's Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS) introduced in 1961, laid the groundwork by allowing multiple terminals to access a central processor, fostering rudimentary forms of synchronous communication beyond batch processing.[26] A pivotal development occurred with the PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations) system at the University of Illinois, operational since 1960 but gaining communication features by the early 1970s. In 1973, programmers Doug Brown and David Woolley developed Talkomatic, recognized as the first multi-user chat room application, which divided the screen into horizontal windows for up to five participants to engage in simultaneous text-based conversations across multiple rooms.[27] [28] PLATO also featured Term-Talk, a one-to-one instant messaging tool invoked by pressing the TERM key and entering "talk," enabling direct peer-to-peer exchanges among users on the system.[29] In parallel, Unix-based environments introduced the 'talk' command in the early 1980s, providing a command-line interface for real-time text communication between users on the same host or networked systems.[30] This tool employed a split-screen format, displaying the sender's and recipient's inputs side-by-side, and became a standard utility on Unix-like operating systems for intra-system messaging before the rise of networked protocols.[31] These early innovations demonstrated the feasibility of low-latency, text-based interpersonal communication in computing, influencing subsequent protocols despite limitations in scalability and graphical interfaces.[32]Pre-Graphical Internet Protocols

Thetalk protocol, integrated into Unix systems via the talk command, facilitated direct, real-time text-based communication between two users across networked machines. Released as part of 4.2BSD in August 1983, it operated over UDP and displayed incoming messages on a split terminal screen, allowing simultaneous typing and viewing without interrupting the conversation.[33] This point-to-point protocol required users to know each other's login names and hostnames, initiating sessions by inviting the remote party, who could accept or decline.[34]

Subsequent enhancements addressed limitations of the original implementation. The ntalk variant, introduced in later BSD releases such as 4.3BSD around 1986, refined the protocol for better compatibility across multi-homed systems and incorporated a more robust negotiation mechanism, though it remained incompatible with the 4.2BSD version.[35] Tools like ytalk, developed in the early 1990s, extended the protocol to support multi-user conversations in a terminal-based interface, splitting the screen into multiple panes for group interaction.[36] These protocols were inherently insecure, transmitting unencrypted plain text over networks and vulnerable to eavesdropping, reflecting the era's minimal emphasis on privacy in academic and research environments.[37]

A significant advancement came with the Internet Relay Chat (IRC) protocol in 1988, created by Jarkko Oikarinen at the University of Oulu to enable multi-user discussions replacing slower BITNET relays.[38] Operating over TCP on port 6667 (standardized later), IRC supported channels for group chats, private messaging, and operator controls, with text-based clients like ircII providing command-line access.[39] Its client-server architecture allowed scalable federation across networks, handling thousands of users, though early deployments faced challenges like net splits due to unstable connections.[40] IRC's plain-text nature enabled simple parsing and extension but exposed it to similar security risks as earlier protocols, including channel flooding and unauthorized access.[41]

These pre-graphical protocols laid foundational mechanics for instant messaging, emphasizing low-latency text exchange over IP networks but lacking features like persistent identities or multimedia, which emerged later with graphical clients. Their terminal-centric design suited command-line environments prevalent in Unix-dominated research institutions during the 1980s.[26]

Emergence of Consumer Clients

The emergence of consumer-oriented instant messaging clients occurred in the mid-1990s, coinciding with the expansion of graphical user interfaces and broader home internet adoption via dial-up services. ICQ, developed by the Israeli firm Mirabilis, launched in November 1996 as the first widely accessible standalone application for real-time text communication over the internet, featuring a user-friendly GUI, unique numerical user identifiers (UINs), buddy lists for presence awareness, and server-mediated message routing that enabled cross-user connections without requiring simultaneous logins for notifications.[42] Unlike earlier command-line tools, ICQ prioritized ease of use for non-technical users, rapidly attracting millions worldwide by emphasizing simplicity and the novelty of instant, asynchronous alerts—such as the iconic "uh-oh" sound for incoming messages—fostering viral adoption through word-of-mouth and free distribution.[43] This breakthrough spurred competition, as established internet portals sought to capture the growing market of personal computing households. AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) debuted on May 1, 1997, initially as a Windows download extending AOL's proprietary ecosystem but soon opening to non-subscribers, introducing customizable away messages, file sharing, and emoticon support that enhanced social expressiveness and tied into AOL's vast user base of over 10 million dial-up subscribers at the time.[44] Yahoo Pager, rebranded as Yahoo Messenger, followed on March 9, 1998, integrating with Yahoo's web portal to offer voice chat prototypes and webcam support earlier than rivals, capitalizing on the search engine's traffic to build a user base rivaling ICQ's.[45] Microsoft entered with MSN Messenger on July 22, 1999, leveraging Windows integration for seamless startup and .NET Passport authentication, which prioritized enterprise-like reliability and later evolved to include emoticon packs and basic encryption amid antitrust scrutiny over interoperability.[46] These clients' success stemmed from network effects: each achieved critical mass through exclusive protocols that locked users into siloed ecosystems, deterring cross-network communication despite early federation attempts, while features like status indicators and typing notifications addressed causal demands for low-latency social coordination in an era of sporadic connectivity. By 1998, AOL acquired Mirabilis for approximately $407 million, reflecting ICQ's explosive growth to over 100 million registered users by 2001, though exact 1996-1997 figures remain anecdotal due to limited tracking; this consolidation intensified proprietary development over open standards.[47] The proliferation marked a shift from niche protocols to mass-market tools, embedding instant messaging in daily consumer routines and presaging mobile dominance, albeit with emergent privacy risks from persistent online presence.[48]Mobile Integration and Dominance

The integration of instant messaging into mobile devices accelerated with the introduction of BlackBerry Messenger (BBM) in 2005, which leveraged push notification technology to deliver real-time text messaging on BlackBerry handsets. BBM gained prominence as BlackBerry captured over 50% of the U.S. smartphone market by 2009 and 20% globally, appealing to users with features such as typing indicators, read receipts, and group chats that preceded similar functionalities in later apps.[49][50] The launch of app stores for iOS in 2008 and Android shortly thereafter enabled widespread adoption of cross-platform instant messaging apps, shifting usage from carrier-dependent SMS—which originated in 1992 but incurred per-message fees—to data-based services. WhatsApp, founded in February 2009 by Jan Koum and Brian Acton, exemplified this transition by offering free, internet-protocol messaging with end-to-end encryption added in 2016, rapidly scaling to 400 million monthly active users by December 2013 amid falling mobile data costs and smartphone proliferation in emerging markets.[51][52] BlackBerry's market share eroded to under 1% by 2016 due to its slower adaptation to open app ecosystems and touchscreen interfaces, leading to BBM's decline and service shutdown in 2019.[50][53] Mobile dominance solidified in the 2010s as proprietary integrations like Apple's iMessage (introduced in 2011 with iOS 5) reinforced ecosystem loyalty, while apps such as WeChat (2011) dominated in China through super-app features. By 2024, mobile messaging apps served nearly 4 billion users worldwide, representing the primary medium for personal and group communication, with WhatsApp alone at 3 billion monthly active users, far outpacing desktop counterparts that had peaked in the early 2000s.[54][55] This supremacy stems from smartphones' portability, always-on connectivity via Wi-Fi and cellular data, and advanced features like voice/video calls and rich media sharing, which rendered legacy desktop protocols like OSCAR or IRC obsolete for consumer use.[56]Privacy-Centric Evolutions

The disclosures of widespread government surveillance programs in 2013, revealed by Edward Snowden, catalyzed a shift toward privacy-enhanced instant messaging protocols, prompting developers to prioritize end-to-end encryption (E2EE) to prevent intermediary access to message contents.[57] Prior to this, most consumer apps like early versions of AIM and MSN Messenger relied on server-side encryption vulnerable to provider subpoenas or breaches, but post-2013 innovations emphasized client-side keys inaccessible to operators.[58] Signal, originally launched as TextSecure in 2010 by Whisper Systems, emerged as a benchmark for privacy-centric design after its 2014 rebranding and open-sourcing of the Signal Protocol, which provides forward secrecy and deniability alongside E2EE for text, voice, and video.[57] This protocol's adoption extended to WhatsApp in 2016, securing over 2 billion users' communications against server interception, though metadata like timestamps and contacts remained collectible by Meta. By 2023, Meta enabled default E2EE in Messenger for private chats, covering billions of interactions but excluding group features initially.[59] Further evolutions addressed metadata leakage and centralization risks, with decentralized protocols gaining traction to distribute control and enhance resilience. Matrix, introduced in 2014, enables federated servers where users can self-host, supporting E2EE via the Olm library derived from Signal's double-ratchet mechanism, and has been used in privacy-sensitive deployments like government communications.[60] Apps like Session, launched in 2018, employ onion routing over a blockchain-inspired network to anonymize IP addresses and eliminate phone number requirements, storing no user data centrally and relying on decentralized nodes for message relay.[61] Older federated standards like XMPP, extensible since 1999, incorporated optional E2EE via plugins such as OMEMO (2015), allowing server diversity but facing challenges from fragmented implementations and discovery issues.[5] These developments reflect a causal progression: E2EE mitigated content exposure, while decentralization targeted surveillance vectors like compelled server data handover, though adoption lags due to usability trade-offs and network effects favoring centralized incumbents.[62] Signal's 2024 introduction of usernames further reduced phone number linkage, underscoring ongoing refinements in anonymity.[63]Features and Functionality

Basic Text and Group Messaging

Instant messaging's core functionality revolves around the real-time exchange of short text messages between users connected via internet protocols, enabling near-instantaneous delivery upon transmission. Defined technically as the transfer of content—primarily textual—among participants with minimal latency, basic text messaging operates through client-server or peer-to-peer architectures where a sender's client encodes the message (typically in UTF-8 for Unicode support) and dispatches it to a recipient's inbox or endpoint.[64] This contrasts with store-and-forward systems like email by prioritizing immediate push notification to online recipients, often supplemented by presence awareness to confirm availability.[65] Messages appear in a persistent, chronological chat interface, fostering synchronous conversation without the delays inherent in cellular SMS, which relies on telephony networks rather than IP.[11] In practice, basic text supports one-to-one exchanges where users compose messages via keyboard input, with protocols like SIP using MESSAGE requests to encapsulate and route payloads as small, identifiable data units.[64] Delivery succeeds if the recipient is online, with offline queuing in some systems to store undelivered texts until reconnection. Enhancements such as delivery receipts or typing indicators—signaling active composition—emerge from protocol extensions but remain optional in minimal implementations.[66] Character limits vary by service, historically capped low (e.g., 140-1024 characters in early protocols) to mimic SMS constraints, though modern clients accommodate longer inputs by segmenting or expanding fields.[67] Group messaging extends one-to-one text by broadcasting a single message to multiple designated participants within a shared conversation channel, distributing it via multicast or server-side replication to all members' clients. This enables collective real-time interaction, where replies append to a common thread visible to the group, supporting coordination among small teams or social circles.[68] Protocols handle group dynamics through dedicated identifiers or rooms, ensuring atomic delivery attempts to all subscribers while managing joins, leaves, and moderation via administrative controls. Early group features, as in protocols like IRC derivatives, emphasized public channels, but proprietary IM evolved to private, invitation-based groups with persistent histories. Scalability limits group sizes—typically 10-250 users in consumer apps—to prevent overload, with larger setups risking latency from fan-out distribution.[17] Unlike basic pairwise chats, groups introduce challenges like message threading for attribution and notification filtering to avoid spam, yet they underpin collaborative use cases without requiring voice or media.[69]Multimedia Extensions

Multimedia extensions in instant messaging enable the sharing of images, audio, video, documents, and other non-text files, augmenting basic text exchanges with richer content. These features emerged progressively, starting with rudimentary file transfers in early protocols and evolving into seamless media handling in contemporary applications.[38][70] File transfer capabilities appeared early, with ICQ introducing direct file exchange upon its 1996 release, allowing users to send binaries including images and executables alongside messages.[38] AOL Instant Messenger similarly incorporated file sharing from its inception in 1997, often linking it to email for broader utility, though without initial virus scanning at firewalls.[70][71] Protocols like XMPP, formalized in the early 2000s, supported extensible file transfers via extensions such as HTTP File Upload, facilitating metadata-protected sharing in federated environments.[5] In the mobile domain, WhatsApp pioneered voice messaging in August 2013, permitting users to record and transmit short audio clips up to 15 seconds initially, which proved popular for nuanced communication in text-limited scenarios.[72][73] Image and video attachments followed suit, with apps like Kik adding multimedia cards for sketches and searches by 2012.[74] Animated content gained prominence later; Facebook Messenger integrated a GIF search button in June 2015, enabling rapid sharing of short looping videos amid the format's resurgence.[75] These extensions, while enhancing expressiveness, introduced challenges like increased bandwidth demands and security risks from unverified media.[71]

Automation and Third-Party Integrations

Many instant messaging platforms provide application programming interfaces (APIs) that enable automation, allowing developers to create bots for tasks such as responding to queries, scheduling messages, and integrating with external services. These features emerged prominently in the mid-2010s as platforms sought to extend functionality beyond peer-to-peer communication, supporting use cases like customer support and workflow automation. For instance, Telegram's Bot API, an HTTP-based interface launched in June 2015, permits bots to interact with users via messages, inline keyboards, and payments, facilitating applications from news alerts to interactive games.[76] Similarly, WhatsApp's Business API, introduced in 2018, supports automated messaging flows, including notifications and chatbots for handling inquiries without human intervention.[77] Third-party integrations further expand automation by linking instant messaging to disparate systems, often through no-code platforms like Zapier and IFTTT. Zapier, for example, connects Telegram to over 8,000 apps, enabling triggers such as posting Slack updates to Telegram channels or syncing CRM data into WhatsApp notifications, with workflows processing millions of tasks daily across integrated services.[78] IFTTT similarly automates Telegram actions, like sending messages based on external events (e.g., weather alerts or calendar reminders), leveraging the platform's bot infrastructure for seamless execution.[79] These tools abstract API complexities, allowing non-developers to build conditional automations, though they impose rate limits and dependency on platform policies to prevent abuse. In open-protocol systems like XMPP (used in clients such as Pidgin), automation has long been possible via extensions for bot scripting, predating proprietary APIs, but adoption remains niche due to fragmentation. Enterprise-oriented messengers, including Slack and Microsoft Teams, offer robust webhook and app marketplaces for integrations with tools like Google Workspace or Salesforce, automating notifications and data syncing in professional environments. However, privacy-focused platforms like Signal limit such features to minimize metadata exposure, prioritizing end-to-end encryption over extensibility. Automation's efficacy depends on API stability and compliance; for WhatsApp, business accounts require Meta approval and template pre-approvals to curb spam, with non-compliance risking suspension.[80] Overall, these capabilities have driven instant messaging toward hybrid human-machine interaction, though they introduce risks like bot-driven misinformation if not moderated.Interoperability and Standards

Proprietary Lock-In

Proprietary instant messaging platforms often rely on closed, non-standardized protocols that confine communication to users within the same service, creating significant barriers to entry for competitors and high switching costs for users. This vendor lock-in is primarily driven by direct network effects, where the utility of the service scales with the size of its user base, making it socially and practically difficult for individuals to migrate without losing connectivity to their contacts. For instance, users face the dilemma of fragmented conversations across multiple apps if they attempt to switch, as proprietary systems like those from Meta or Apple do not natively interoperate.[81][82] Apple's iMessage exemplifies this dynamic, as its proprietary implementation—introduced in 2011—prioritizes seamless, feature-rich experiences exclusively among iOS devices, while reverting to unencrypted SMS for Android users, marked by green bubbles that signal inferior quality and lack of end-to-end encryption. This visual and functional distinction has been identified as a deliberate lock-in mechanism, reinforcing ecosystem loyalty by imposing social penalties on non-Apple users, such as reduced message quality and exclusion from features like effects and read receipts. Critics argue this contributes to Apple's market dominance in the U.S. smartphone segment, where iMessage's network effects deter users from alternatives despite superior hardware competition from Android devices.[83][83] WhatsApp, owned by Meta, similarly leverages proprietary protocols to sustain over 2 billion monthly active users globally, where network effects amplify lock-in through ubiquitous adoption in regions like India and Europe, rendering alternatives inviable due to incomplete contact networks and data migration challenges. Regulatory scrutiny has highlighted how these effects, combined with data sharing policies, entrench dominance by raising barriers for new entrants and complicating user exodus, as evidenced in competition probes finding abuse via privacy policy updates that indirectly bolster retention.[82][82] Efforts to mitigate proprietary lock-in include the European Union's Digital Markets Act (DMA), enacted in 2022 and fully applicable from 2024, which designates "gatekeeper" services like WhatsApp and iMessage as requiring interoperability with third-party messaging apps for core functions such as text and voice calls, aiming to erode closed ecosystems while preserving end-to-end encryption. Gatekeepers must respond to interoperability requests within three months, with phased rollout starting March 7, 2024, though implementation poses technical hurdles like protocol bridging without compromising security. Meta has proposed opt-in mechanisms for third-party access to WhatsApp, emphasizing user safeguards, yet skeptics note that voluntary compliance may underdeliver compared to mandated standards.[84][85][86][87]Open Protocols and Federation Attempts

The Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP), originally developed by the open-source Jabber community in 1999, serves as a foundational open standard for decentralized instant messaging.[88] Formalized by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) through RFCs such as 6120 and 6121 in 2011, XMPP enables federation among independent servers, allowing users on different XMPP servers to exchange messages and presence information seamlessly, analogous to email federation via SMTP.[5] This architecture supports extensibility through XML streams, facilitating features like multi-user chat and file transfer, and has been implemented in clients such as Pidgin and Gajim.[89] Matrix, an open protocol initiated in 2014 by the Matrix.org foundation, represents a modern effort to standardize secure, decentralized real-time communication, including instant messaging.[60] It employs a federated model where homeservers synchronize event histories across the network, enabling interoperability between disparate services via bridges to protocols like IRC or Slack.[90] Matrix emphasizes end-to-end encryption by default and has gained traction in enterprise and open-source communities, though its resource-intensive synchronization can pose scalability challenges compared to centralized alternatives.[91] Other open protocols, such as the Session Initiation Protocol for Instant Messaging and Presence Leveraging Extensions (SIMPLE) based on SIP, have seen limited adoption due to complexity and lack of widespread server federation.[6] Internet Relay Chat (IRC), dating to 1988, supports server linking but prioritizes channel-based group communication over one-to-one messaging federation.[92] Attempts to impose federation on proprietary platforms have primarily arisen from regulatory pressures rather than voluntary adoption. Under the European Union's Digital Markets Act (DMA), effective March 2024, designated gatekeepers like Meta must enable interoperability between their services—such as WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger—and third-party messaging apps by 2025, potentially via standardized APIs while attempting to maintain end-to-end encryption.[87] However, implementation faces technical hurdles, including metadata leakage risks and spam proliferation, with Meta emphasizing user opt-in and security audits to mitigate vulnerabilities inherent in bridging siloed ecosystems.[87] Historical efforts, like Google's temporary XMPP federation in Google Talk until its 2013 discontinuation, illustrate how proprietary providers often abandon open interoperability to consolidate user data and enhance proprietary features.[93] These dynamics underscore that while open protocols enable federation in principle, network effects and control incentives have confined their success to niche, technically oriented user bases.Technical Barriers and Solutions