Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Usenet

View on Wikipedia

Notably, clients never connect with each other, but still have access to each other's posts even when they also never connect to the same server.

| Internet history timeline |

|

Early research and development:

Merging the networks and creating the Internet:

Commercialization, privatization, broader access leads to the modern Internet:

Examples of Internet services:

|

Usenet (/ˈjuːznɛt/),[1] a portmanteau of User's Network,[1] is a worldwide distributed discussion system available on computers. It was developed from the general-purpose Unix-to-Unix Copy (UUCP) dial-up network architecture. Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis conceived the idea in 1979, and it was established in 1980.[2] Users read and post messages (called articles or posts, and collectively termed news) to one or more topic categories, known as newsgroups. Usenet resembles a bulletin board system (BBS) in many respects and is the precursor to the Internet forums that have become widely used. Discussions are threaded, as with web forums and BBSes, though posts are stored on the server sequentially.[3][4]

A major difference between a BBS or web message board and Usenet is the absence of a central server and dedicated administrator or hosting provider. Usenet is distributed among a large, constantly changing set of news servers that store and forward messages to one another via "news feeds". Individual users may read messages from and post to a local (or simply preferred) news server, which can be operated by anyone, and those posts will automatically be forwarded to any other news servers peered with the local one, while the local server will receive any news its peers have that it currently lacks. This results in the automatic proliferation of content posted by any user on any server to any other user subscribed to the same newsgroups on other servers.

As with BBSes and message boards, individual news servers or service providers are under no obligation to carry any specific content, and may refuse to do so for many reasons: a news server might attempt to control the spread of spam by refusing to accept or forward any posts that trigger spam filters, or a server without high-capacity data storage may refuse to carry any newsgroups used primarily for file sharing, limiting itself to discussion-oriented groups. However, unlike BBSes and web forums, the dispersed nature of Usenet usually permits users who are interested in receiving some content to access it simply by choosing to connect to news servers that carry the feeds they want.

Usenet is culturally and historically significant in the networked world, having given rise to, or popularized, many widely recognized concepts and terms such as "FAQ", "flame", "sockpuppet", and "spam".[5] In the early 1990s, shortly before access to the Internet became commonly affordable, Usenet connections via FidoNet's dial-up BBS networks made long-distance or worldwide discussions and other communication widespread.[6]

| Part of a series on |

| File sharing |

|---|

|

The name Usenet comes from the term "users' network".[3] The first Usenet group was NET.general, which quickly became net.general.[7] The first commercial spam on Usenet was from immigration attorneys Canter and Siegel advertising green card services.[7]

On the Internet, Usenet is transported via the Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP) on Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) port 119 for standard, unprotected connections, and on TCP port 563 for Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) encrypted connections.

Introduction

[edit]Usenet was conceived in 1979 and publicly established in 1980, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University,[8][2] over a decade before the World Wide Web went online (and thus before the general public received access to the Internet), making it one of the oldest computer network communications systems still in widespread use. It was originally built on the "poor man's ARPANET", employing UUCP as its transport protocol to offer mail and file transfers, as well as announcements through the newly developed news software such as A News. The name "Usenet" emphasizes its creators' hope that the USENIX organization would take an active role in its operation.[9]

The articles that users post to Usenet are organized into topical categories known as newsgroups, which are themselves logically organized into hierarchies of subjects. For instance, sci.math and sci.physics are within the sci.* hierarchy. Or, talk.origins and talk.atheism are in the talk.* hierarchy. When a user subscribes to a newsgroup, the news client software keeps track of which articles that user has read.[10]

In most newsgroups, the majority of the articles are responses to some other article. The set of articles that can be traced to one single non-reply article is called a thread. Most modern newsreaders display the articles arranged into threads and subthreads. For example, in the wine-making newsgroup rec.crafts.winemaking, someone might start a thread called; "What's the best yeast?" and that thread or conversation might grow into dozens of replies long, by perhaps six or eight different authors. Over several days, that conversation about different wine yeasts might branch into several sub-threads in a tree-like form.

When a user posts an article, it is initially only available on that user's news server. Each news server talks to one or more other servers (its "newsfeeds") and exchanges articles with them. In this fashion, the article is copied from server to server and should eventually reach every server in the network. The later peer-to-peer networks operate on a similar principle, but for Usenet it is normally the sender, rather than the receiver, who initiates transfers. Usenet was designed under conditions when networks were much slower and not always available. Many sites on the original Usenet network would connect only once or twice a day to batch-transfer messages in and out.[11] This is largely because the POTS network was typically used for transfers, and phone charges were lower at night.

The format and transmission of Usenet articles is similar to that of Internet e-mail messages. The difference between the two is that Usenet articles can be read by any user whose news server carries the group to which the message was posted, as opposed to email messages, which have one or more specific recipients.[12]

Today, Usenet has diminished in importance with respect to Internet forums, blogs, mailing lists and social media. Usenet differs from such media in several ways: Usenet requires no personal registration with the group concerned; information need not be stored on a remote server; archives are always available; and reading the messages does not require a mail or web client, but a news client. However, it is now possible to read and participate in Usenet newsgroups to a large degree using ordinary web browsers since most newsgroups are now copied to several web sites.[13] The groups in alt.binaries are still widely used for data transfer.

ISPs, news servers, and newsfeeds

[edit]

Many Internet service providers, and many other Internet sites, operate news servers for their users to access. ISPs that do not operate their own servers directly will often offer their users an account from another provider that specifically operates newsfeeds. In early news implementations, the server and newsreader were a single program suite, running on the same system. Today, one uses separate newsreader client software, a program that resembles an email client but accesses Usenet servers instead.[14]

Not all ISPs run news servers. A news server is one of the most difficult Internet services to administer because of the large amount of data involved, small customer base (compared to mainstream Internet service), and a disproportionately high volume of customer support incidents (frequently complaining of missing news articles). Some ISPs outsource news operations to specialist sites, which will usually appear to a user as though the ISP itself runs the server. Many of these sites carry a restricted newsfeed, with a limited number of newsgroups. Commonly omitted from such a newsfeed are foreign-language newsgroups and the alt.binaries hierarchy which largely carries software, music, videos and images, and accounts for over 99 percent of article data.[citation needed]

There are also Usenet providers that offer a full unrestricted service to users whose ISPs do not carry news, or that carry a restricted feed.[citation needed]

Newsreaders

[edit]Newsgroups are typically accessed with newsreaders: applications that allow users to read and reply to postings in newsgroups. These applications act as clients to one or more news servers. Historically, Usenet was associated with the Unix operating system developed at AT&T, but newsreaders were soon available for all major operating systems.[15] Email client programs and Internet suites of the late 1990s and 2000s often included an integrated newsreader. Newsgroup enthusiasts often criticized these as inferior to standalone newsreaders that made correct use of Usenet protocols, standards and conventions.[16]

With the rise of the World Wide Web (WWW), web front-ends (web2news) have become more common. Web front ends have lowered the technical entry barrier requirements to that of one application and no Usenet NNTP server account. There are numerous websites now offering web based gateways to Usenet groups, although some people have begun filtering messages made by some of the web interfaces for one reason or another.[17][18] Google Groups[19] is one such web based front end and some web browsers can access Google Groups via news: protocol links directly.[20]

Moderated and unmoderated newsgroups

[edit]A minority of newsgroups are moderated, meaning that messages submitted by readers are not distributed directly to Usenet, but instead are emailed to the moderators of the newsgroup for approval. The moderator is to receive submitted articles, review them, and inject approved articles so that they can be properly propagated worldwide. Articles approved by a moderator must bear the Approved: header line. Moderators ensure that the messages that readers see in the newsgroup conform to the charter of the newsgroup, though they are not required to follow any such rules or guidelines.[21] Typically, moderators are appointed in the proposal for the newsgroup, and changes of moderators follow a succession plan.[22]

Historically, a mod.* hierarchy existed before Usenet reorganization.[23] Now, moderated newsgroups may appear in any hierarchy, typically with .moderated added to the group name.

Usenet newsgroups in the Big-8 hierarchy are created by proposals called a Request for Discussion, or RFD. The RFD is required to have the following information: newsgroup name, checkgroups file entry, and moderated or unmoderated status. If the group is to be moderated, then at least one moderator with a valid email address must be provided. Other information which is beneficial but not required includes: a charter, a rationale, and a moderation policy if the group is to be moderated.[24] Discussion of the new newsgroup proposal follows, and is finished with the members of the Big-8 Management Board making the decision, by vote, to either approve or disapprove the new newsgroup.

Unmoderated newsgroups form the majority of Usenet newsgroups, and messages submitted by readers for unmoderated newsgroups are immediately propagated for everyone to see. Minimal editorial content filtering vs propagation speed form one crux of the Usenet community. One little cited defense of propagation is canceling a propagated message, but few Usenet users use this command and some news readers do not offer cancellation commands, in part because article storage expires in relatively short order anyway. Almost all unmoderated Usenet groups tend to receive large amounts of spam.[25][26][27]

Technical details

[edit]Usenet is a set of protocols for generating, storing and retrieving news "articles" (which resemble Internet mail messages) and for exchanging them among a readership which is potentially widely distributed. These protocols most commonly use a flooding algorithm which propagates copies throughout a network of participating servers. Whenever a message reaches a server, that server forwards the message to all its network neighbors that haven't yet seen the article. Only one copy of a message is stored per server, and each server makes it available on demand to the (typically local) readers able to access that server. The collection of Usenet servers has thus a certain peer-to-peer character in that they share resources by exchanging them, the granularity of exchange however is on a different scale than a modern peer-to-peer system and this characteristic excludes the actual users of the system who connect to the news servers with a typical client-server application, much like an email reader.

RFC 850 was the first formal specification of the messages exchanged by Usenet servers. It was superseded by RFC 1036 and subsequently by RFC 5536 and RFC 5537.

In cases where unsuitable content has been posted, Usenet has support for automated removal of a posting from the whole network by creating a cancel message, although due to a lack of authentication and resultant abuse, this capability is frequently disabled. Copyright holders may still request the manual deletion of infringing material using the provisions of World Intellectual Property Organization treaty implementations, such as the United States Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act, but this would require giving notice to each individual news server administrator.

On the Internet, Usenet is transported via the Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP) on TCP Port 119 for standard, unprotected connections and on TCP port 563 for SSL encrypted connections.

Organization

[edit]

The major set of worldwide newsgroups is contained within nine hierarchies, eight of which are operated under consensual guidelines that govern their administration and naming. The current Big Eight are:

- comp.* – computer-related discussions (comp.software, comp.sys.amiga)

- humanities.* – fine arts, literature, and philosophy (humanities.classics, humanities.design.misc)

- misc.* – miscellaneous topics (misc.education, misc.forsale, misc.kids)

- news.* – discussions and announcements about news (meaning Usenet, not current events) (news.groups, news.admin)

- rec.* – recreation and entertainment (rec.music, rec.arts.movies)

- sci.* – science related discussions (sci.psychology, sci.research)

- soc.* – social discussions (soc.college.org, soc.culture.african)

- talk.* – talk about various controversial topics (talk.religion, talk.politics, talk.origins)

The alt.* hierarchy is not subject to the procedures controlling groups in the Big Eight, and it is as a result less organized. Groups in the alt.* hierarchy tend to be more specialized or specific—for example, there might be a newsgroup under the Big Eight which contains discussions about children's books, but a group in the alt hierarchy may be dedicated to one specific author of children's books. Binaries are posted in alt.binaries.*, making it the largest of all the hierarchies.

Many other hierarchies of newsgroups are distributed alongside these. Regional and language-specific hierarchies such as japan.*, malta.* and ne.* serve specific countries and regions such as Japan, Malta and New England. Companies and projects administer their own hierarchies to discuss their products and offer community technical support, such as the historical gnu.* hierarchy from the Free Software Foundation. Microsoft closed its newsserver in June 2010, providing support for its products over forums now.[28] Some users prefer to use the term "Usenet" to refer only to the Big Eight hierarchies; others include alt.* as well. The more general term "netnews" incorporates the entire medium, including private organizational news systems.

Informal sub-hierarchy conventions also exist. *.answers are typically moderated cross-post groups for FAQs. An FAQ would be posted within one group and a cross post to the *.answers group at the head of the hierarchy seen by some as a refining of information in that news group. Some subgroups are recursive—to the point of some silliness in alt.*[citation needed].

Binary content

[edit]

Usenet was originally created to distribute text content encoded in the 7-bit ASCII character set. With the help of programs that encode 8-bit values into ASCII, it became practical to distribute binary files as content. Binary posts, due to their size and often-dubious copyright status, were in time restricted to specific newsgroups, making it easier for administrators to allow or disallow the traffic.

The oldest widely used encoding method for binary content is uuencode, from the Unix UUCP package. In the late 1980s, Usenet articles were often limited to 60,000 characters, and larger hard limits exist today. Files are therefore commonly split into sections that require reassembly by the reader.

With the header extensions and the Base64 and Quoted-Printable MIME encodings, there was a new generation of binary transport. In practice, MIME has seen increased adoption in text messages, but it is avoided for most binary attachments. Some operating systems with metadata attached to files use specialized encoding formats. For Mac OS, both BinHex and special MIME types are used. Other lesser known encoding systems that may have been used at one time were BTOA, XX encoding, BOO, and USR encoding.

In an attempt to reduce file transfer times, an informal file encoding known as yEnc was introduced in 2001. It achieves about a 30% reduction in data transferred by assuming that most 8-bit characters can safely be transferred across the network without first encoding into the 7-bit ASCII space. The most common method of uploading large binary posts to Usenet is to convert the files into RAR archives and create Parchive files for them. Parity files are used to recreate missing data when not every part of the files reaches a server.

Binary newsgroups can be used to distribute files, and, as of 2022, some remain popular as an alternative to BitTorrent to share and download files.[29]

Binary retention time

[edit]

Each news server allocates a certain amount of storage space for content in each newsgroup. When this storage has been filled, each time a new post arrives, old posts are deleted to make room for the new content. If the network bandwidth available to a server is high but the storage allocation is small, it is possible for a huge flood of incoming content to overflow the allocation and push out everything that was in the group before it. The average length of time that posts are able to stay on the server before being deleted is commonly called the retention time.

Binary newsgroups are only able to function reliably if there is sufficient storage allocated to handle the amount of articles being added. Without sufficient retention time, a reader will be unable to download all parts of the binary before it is flushed out of the group's storage allocation. This was at one time how posting undesired content was countered; the newsgroup would be flooded with random garbage data posts, of sufficient quantity to push out all the content to be suppressed. This has been compensated by service providers allocating enough storage to retain everything posted each day, including spam floods, without deleting anything.

Modern Usenet news servers have enough capacity to archive years of binary content even when flooded with new data at the maximum daily speed available.

In part because of such long retention times, as well as growing Internet upload speeds, Usenet is also used by individual users to store backup data.[31] While commercial providers offer easier to use online backup services, storing data on Usenet is free of charge (although access to Usenet itself may not be). The method requires the uploader to cede control over the distribution of the data; the files are automatically disseminated to all Usenet providers exchanging data for the news group it is posted to. In general the user must manually select, prepare and upload the data. The data is typically encrypted because it is available to anyone to download the backup files. After the files are uploaded, having multiple copies spread to different geographical regions around the world on different news servers decreases the chances of data loss.

Major Usenet service providers have a retention time of more than 12 years.[32] This results in more than 60 petabytes (60000 terabytes) of storage (see image). When using Usenet for data storage, providers that offer longer retention time are preferred to ensure the data will survive for longer periods of time compared to services with lower retention time.

Legal issues

[edit]While binary newsgroups can be used to distribute completely legal user-created works, free software, and public domain material, some binary groups are used to illegally distribute proprietary software, copyrighted media, and pornographic material.

ISP-operated Usenet servers frequently block access to all alt.binaries.* groups to both reduce network traffic and to avoid related legal issues. Commercial Usenet service providers claim to operate as a telecommunications service, and assert that they are not responsible for the user-posted binary content transferred via their equipment. In the United States, Usenet providers can qualify for protection under the DMCA Safe Harbor regulations, provided that they establish a mechanism to comply with and respond to takedown notices from copyright holders.[33]

Removal of copyrighted content from the entire Usenet network is a nearly impossible task, due to the rapid propagation between servers and the retention done by each server. Petitioning a Usenet provider for removal only removes it from that one server's retention cache, but not any others. It is possible for a special post cancellation message to be distributed to remove it from all servers, but many providers ignore cancel messages by standard policy, because they can be easily falsified and submitted by anyone.[34][35] For a takedown petition to be most effective across the whole network, it would have to be issued to the origin server to which the content has been posted, before it has been propagated to other servers. Removal of the content at this early stage would prevent further propagation, but with modern high speed links, content can be propagated as fast as it arrives, allowing no time for content review and takedown issuance by copyright holders.[36]

Establishing the identity of the person posting illegal content is equally difficult due to the trust-based design of the network. Like SMTP email, servers generally assume the header and origin information in a post is true and accurate. However, as in SMTP email, Usenet post headers are easily falsified so as to obscure the true identity and location of the message source.[37] In this manner, Usenet is significantly different from modern P2P services; most P2P users distributing content are typically immediately identifiable to all other users by their network address, but the origin information for a Usenet posting can be completely obscured and unobtainable once it has propagated past the original server.[38]

Also unlike modern P2P services, the identity of the downloaders is hidden from view. On P2P services a downloader is identifiable to all others by their network address. On Usenet, the downloader connects directly to a server, and only the server knows the address of who is connecting to it. Some Usenet providers do keep usage logs, but not all make this logged information casually available to outside parties such as the Recording Industry Association of America.[39][40][41] The existence of anonymising gateways to USENET also complicates the tracing of a postings true origin.

History

[edit]Newsgroup experiments first occurred in 1979. Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis of Duke University came up with the idea as a replacement for a local announcement program, and established a link with nearby University of North Carolina using Bourne shell scripts written by Steve Bellovin. The public release of news was in the form of conventional compiled software, written by Steve Daniel and Truscott.[8][43] In 1980, Usenet was connected to ARPANET through UC Berkeley, which had connections to both Usenet and ARPANET. Mary Ann Horton, the graduate student who set up the connection, began "feeding mailing lists from the ARPANET into Usenet" with the "fa" ("From ARPANET"[44]) identifier.[45] Usenet gained 50 member sites in its first year, including Reed College, University of Oklahoma, and Bell Labs,[8] and the number of people using the network increased dramatically; however, it was still a while longer before Usenet users could contribute to ARPANET.[46]

Network

[edit]UUCP networks spread quickly due to the lower costs involved, and the ability to use existing leased lines, X.25 links or even ARPANET connections. By 1983, thousands of people participated from more than 500 hosts, mostly universities and Bell Labs sites but also a growing number of Unix-related companies; the number of hosts nearly doubled to 940 in 1984. More than 100 newsgroups existed, more than 20 devoted to Unix and other computer-related topics, and at least a third to recreation.[47][8] As the mesh of UUCP hosts rapidly expanded, it became desirable to distinguish the Usenet subset from the overall network. A vote was taken at the 1982 USENIX conference to choose a new name. The name Usenet was retained, but it was established that it only applied to news.[48] The name UUCPNET became the common name for the overall network.

In addition to UUCP, early Usenet traffic was also exchanged with FidoNet and other dial-up BBS networks. By the mid-1990s there were almost 40,000 FidoNet systems in operation, and it was possible to communicate with millions of users around the world, with only local telephone service. Widespread use of Usenet by the BBS community was facilitated by the introduction of UUCP feeds made possible by MS-DOS implementations of UUCP, such as UFGATE (UUCP to FidoNet Gateway), FSUUCP and UUPC. In 1986, RFC 977 provided the Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP) specification for distribution of Usenet articles over TCP/IP as a more flexible alternative to informal Internet transfers of UUCP traffic. Since the Internet boom of the 1990s, almost all Usenet distribution is over NNTP.[49]

Software

[edit]Early versions of Usenet used Duke's A News software, designed for one or two articles a day. Matt Glickman and Horton at Berkeley produced an improved version called B News that could handle the rising traffic (about 50 articles a day as of late 1983).[8] With a message format that offered compatibility with Internet mail and improved performance, it became the dominant server software. C News, developed by Geoff Collyer and Henry Spencer at the University of Toronto, was comparable to B News in features but offered considerably faster processing. In the early 1990s, InterNetNews by Rich Salz was developed to take advantage of the continuous message flow made possible by NNTP versus the batched store-and-forward design of UUCP. Since that time INN development has continued, and other news server software has also been developed.[50]

Public venue

[edit]Usenet was the first Internet community and the place for many of the most important public developments in the pre-commercial Internet. It was the place where Tim Berners-Lee announced the launch of the World Wide Web,[51] where Linus Torvalds announced the Linux project,[52] and where Marc Andreessen announced the creation of the Mosaic browser and the introduction of the image tag,[53] which revolutionized the World Wide Web by turning it into a graphical medium.

Internet jargon and history

[edit]Many jargon terms now in common use on the Internet originated or were popularized on Usenet.[54] Likewise, many conflicts which later spread to the rest of the Internet, such as the ongoing difficulties over spamming, began on Usenet.[55]

"Usenet is like a herd of performing elephants with diarrhea. Massive, difficult to redirect, awe-inspiring, entertaining, and a source of mind-boggling amounts of excrement when you least expect it."

— Gene Spafford, 1992

Decline

[edit]Sascha Segan of PC Magazine said in 2008 that "Usenet has been dying for years".[56] He argued that it was dying by the late 1990s, when large binary files became a significant proportion of Usenet traffic, and Internet service providers "sensibly started to wonder why they should be reserving big chunks of their own disk space for pirated movies and repetitive porn."

AOL discontinued Usenet access in 2005. In May 2010, Duke University, whose implementation had started Usenet more than 30 years earlier, decommissioned its Usenet server, citing low usage and rising costs.[57][58] On February 4, 2011, the Usenet news service link at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (news.unc.edu) was retired after 32 years.[citation needed]

In response, John Biggs of TechCrunch said "As long as there are folks who think a command line is better than a mouse, the original text-only social network will live on".[59] While there are still some active text newsgroups on Usenet, the system is now primarily used to share large files between users, and the underlying technology of Usenet remains unchanged.[60]

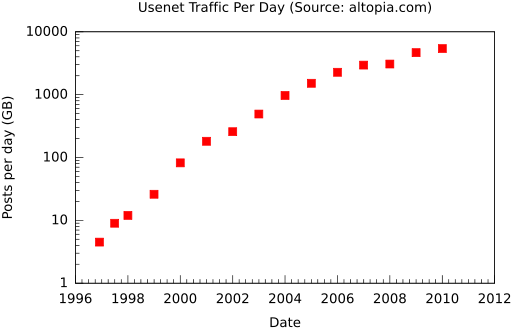

Usenet traffic changes

[edit]Over time, the amount of Usenet traffic has steadily increased. As of 2010[update] the number of all text posts made in all Big-8 newsgroups averaged 1,800 new messages every hour, with an average of 25,000 messages per day.[61] However, these averages are minuscule in comparison to the traffic in the binary groups.[62] Much of this traffic increase reflects not an increase in discrete users or newsgroup discussions, but instead the combination of massive automated spamming and an increase in the use of .binaries newsgroups[61] in which large files are often posted publicly. A small sampling of the change (measured in feed size per day) follows:

| Daily volume | Daily posts | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 4.5 GiB | 1996 Dec | |

| 9 GiB | 1997 Jul | |

| 12 GiB | 554 k | 1998 Jan |

| 26 GiB | 609 k | 1999 Jan |

| 82 GiB | 858 k | 2000 Jan |

| 181 GiB | 1.24 M | 2001 Jan |

| 257 GiB | 1.48 M | 2002 Jan |

| 492 GiB | 2.09 M | 2003 Jan |

| 969 GiB | 3.30 M | 2004 Jan |

| 1.52 TiB | 5.09 M | 2005 Jan |

| 2.27 TiB | 7.54 M | 2006 Jan |

| 2.95 TiB | 9.84 M | 2007 Jan |

| 3.07 TiB | 10.13 M | 2008 Jan |

| 4.65 TiB | 14.64 M | 2009 Jan |

| 5.42 TiB | 15.66 M | 2010 Jan |

| 7.52 TiB | 20.12 M | 2011 Jan |

| 9.29 TiB | 23.91 M | 2012 Jan |

| 11.49 TiB | 28.14 M | 2013 Jan |

| 14.61 TiB | 37.56 M | 2014 Jan |

| 17.87 TiB | 44.19 M | 2015 Jan |

| 23.87 TiB | 55.59 M | 2016 Jan |

| 27.80 TiB | 64.55 M | 2017 Jan |

| 37.35 TiB | 73.95 M | 2018 Jan |

| 60.38 TiB | 104.04 M | 2019 Jan |

| 62.40 TiB | 107.49 M | 2020 Jan |

| 100.71 TiB | 171.86 M | 2021 Jan |

| 220.00 TiB[64] | 279.16 M | 2023 Aug |

| 274.49 TiB | 400.24 M | 2024 Feb |

In 2008, Verizon Communications, Time Warner Cable and Sprint Nextel signed an agreement with Attorney General of New York Andrew Cuomo to shut down access to sources of child pornography.[65] Time Warner Cable stopped offering access to Usenet. Verizon reduced its access to the "Big 8" hierarchies. Sprint stopped access to the alt.* hierarchies. AT&T stopped access to the alt.binaries.* hierarchies. Cuomo never specifically named Usenet in his anti-child pornography campaign. David DeJean of PC World said that some worry that the ISPs used Cuomo's campaign as an excuse to end portions of Usenet access, as it is costly for the Internet service providers and not in high demand by customers. In 2008 AOL, which no longer offered Usenet access, and the four providers that responded to the Cuomo campaign were the five largest Internet service providers in the United States; they had more than 50% of the U.S. ISP market share.[66] On June 8, 2009, AT&T announced that it would no longer provide access to the Usenet service as of July 15, 2009.[67]

AOL announced that it would discontinue its integrated Usenet service in early 2005, citing the growing popularity of weblogs, chat forums and on-line conferencing.[68] The AOL community had a tremendous role in popularizing Usenet some 11 years earlier.[69]

In August 2009, Verizon announced that it would discontinue access to Usenet on September 30, 2009.[70][71] JANET announced it would discontinue Usenet service, effective July 31, 2010, citing Google Groups as an alternative.[72] Microsoft announced that it would discontinue support for its public newsgroups (msnews.microsoft.com) from June 1, 2010, offering web forums as an alternative.[73]

Primary reasons cited for the discontinuance of Usenet service by general ISPs include the decline in volume of actual readers due to competition from blogs, along with cost and liability concerns of increasing proportion of traffic devoted to file-sharing and spam on unused or discontinued groups.[74][75]

Some ISPs did not include pressure from Cuomo's campaign against child pornography as one of their reasons for dropping Usenet feeds as part of their services.[76] ISPs Cox and Atlantic Communications resisted the 2008 trend but both did eventually drop their respective Usenet feeds in 2010.[77][78][79]

Archives

[edit]Public archives of Usenet articles have existed since the early days of Usenet, such as the system created by Kenneth Almquist in late 1982.[80][81] Distributed archiving of Usenet posts was suggested in November 1982 by Scott Orshan, who proposed that "Every site should keep all the articles it posted, forever."[82] Also in November of that year, Rick Adams responded to a post asking "Has anyone archived netnews, or does anyone plan to?"[83] by stating that he was, "afraid to admit it, but I started archiving most 'useful' newsgroups as of September 18."[84] In June 1982, Gregory G. Woodbury proposed an "automatic access to archives" system that consisted of "automatic answering of fixed-format messages to a special mail recipient on specified machines."[85]

In 1985, two news archiving systems and one RFC were posted to the Internet. The first system, called keepnews, by Mark M. Swenson of the University of Arizona, was described as "a program that attempts to provide a sane way of extracting and keeping information that comes over Usenet." The main advantage of this system was to allow users to mark articles as worthwhile to retain.[86] The second system, YA News Archiver by Chuq Von Rospach, was similar to keepnews, but was "designed to work with much larger archives where the wonderful quadratic search time feature of the Unix ... becomes a real problem."[87] Von Rospach in early 1985 posted a detailed RFC for "archiving and accessing usenet articles with keyword lookup." This RFC described a program that could "generate and maintain an archive of Usenet articles and allow looking up articles based on the article-id, subject lines, or keywords pulled out of the article itself." Also included was C code for the internal data structure of the system.[88]

The desire to have a full text search index of archived news articles is not new either, one such request having been made in April 1991 by Alex Martelli who sought to "build some sort of keyword index for [the news archive]."[89] In early May, Martelli posted a summary of his responses to Usenet, noting that the "most popular suggestion award must definitely go to 'lq-text' package, by Liam Quin, recently posted in alt.sources."[90]

The Alt Sex Stories Text Repository (ASSTR) site archived and indexed erotic and pornographic stories posted to the Usenet group alt.sex.stories.[91]

The archiving of Usenet has led to fears of loss of privacy.[92] An archive simplifies ways to profile people. This has partly been countered with the introduction of the X-No-Archive: Yes header, which is itself controversial.[93]

Archives by Deja News and Google Groups

[edit]Web-based archiving of Usenet posts began in March 1995 at Deja News with a very large, searchable database. In February 2001, this database was acquired by Google;[94] Google had begun archiving Usenet posts for itself starting in the second week of August 2000.

Google Groups hosts an archive of Usenet posts dating back to May 1981. The earliest posts, which date from May 1981 to June 1991, were donated to Google by the University of Western Ontario with the help of David Wiseman and others,[95] and were originally archived by Henry Spencer at the University of Toronto's Zoology department.[96] The archives for late 1991 through early 1995 were provided by Kent Landfield from the NetNews CD series[97] and Jürgen Christoffel from GMD.[98]

Google has been criticized by Vice and Wired contributors as well as former employees for its stewardship of the archive and for breaking its search functionality.[99][100][101]

As of January 2024, Google Groups carries a header notice, saying:

Effective from 22 February 2024, Google Groups will no longer support new Usenet content. Posting and subscribing will be disallowed, and new content from Usenet peers will not appear. Viewing and searching of historical data will still be supported as it is done today.

An explanatory page adds:[102]

In addition, Google’s Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP) server and associated peering will no longer be available, meaning Google will not support serving new Usenet content or exchanging content with other NNTP servers. This change will not impact any non-Usenet content on Google Groups, including all user and organization-created groups.

See also

[edit]Usenet newsreaders

[edit]Usenet/newsgroup service providers

[edit]Usenet history

[edit]Usenet administrators

[edit]Usenet had administrators on a server-by-server basis, not as a whole. A few famous administrators:

- Chris Lewis

- Gene Spafford, a.k.a. Spaf

- Henry Spencer

- Kai Puolamäki

- Mary Ann Horton

References

[edit]- ^ a b Hosch, William L.; Gregersen, Erik (May 17, 2021). "USENET". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ a b From Usenet to CoWebs: interacting with social information spaces, Christopher Lueg, Danyel Fisher, Springer (2003), ISBN 1-85233-532-7, ISBN 978-1-85233-532-8

- ^ a b The jargon file v4.4.7 Archived January 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Jargon File Archive.

- ^ Chapter 3 - The Social Forces Behind The Development of Usenet Archived August 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Netizens Netbook by Ronda Hauben and Michael Hauben.

- ^ "USENET Newsgroup Terms – SPAM". Archived from the original on September 15, 2012.

- ^ Pre-Internet; Usenet needing "just local telephone service" in most larger towns, depends on the number of local dial-up FidoNet "nodes" operated free of charge by hobbyist "SysOps" (as FidoNet echomail variations or via gateways with the Usenet news hierarchy. This is virtual Usenet or newsgroups access, not true Usenet.) The participating SysOps typically carry 6–30 Usenet newsgroups each, and will often add another on request. If a desired newsgroup was not available locally, a user would need to dial to another city to download the desired news and upload one's own posts. In all cases it is desirable to hang up as soon as possible and read/write offline, making "newsreader" software commonly used to automate the process. Fidonet, bbscorner.com Archived February 7, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

fidonet.org, Randy_Bush.txt Archived December 3, 2003, at the Wayback Machine - ^ a b Bonnett, Cara (May 17, 2010). "Duke to shut Usenet server, home to the first electronic newsgroups". Duke University. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Emerson, Sandra L. (October 1983). "Usenet / A Bulletin Board for Unix Users". BYTE. pp. 219–236. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ "Invitation to a General Access UNIX Network Archived September 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine", James Ellis and Tom Truscott, in First Official Announcement of USENET, NewsDemon (K&L Technologies, Inc), 1979

- ^ Lehnert, Wendy G.; Kopec, Richard (2007). Web 101. Addison Wesley. p. 291. ISBN 9780321424679

- ^ "Store And Forward Communication: UUCP and FidoNet". Archived from the original on June 30, 2012.. Carnegie Mellon School of Computer Science.

- ^ Kozierok, Charles M. (2005). The TCP/IP guide: a comprehensive, illustrated Internet protocols reference. No Starch Press. p. 1401. ISBN 978-159327-047-6

- ^ One way to virtually read and participate in Usenet newsgroups using an ordinary Internet browser is to do an internet search on a known newsgroup, such as the high volume forum: "sci.physics". Retrieved April 28, 2019

- ^ "Best Usenet clients". UsenetReviewz. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- ^ "Open Directory Usenet Clients". Dmoz.org. October 9, 2008. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ Jain, Dominik (July 30, 2006). "OE-QuoteFix Description". Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ^ "Improve-Usenet". October 13, 2008. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012.

- ^ "Improve-Usenet Comments". October 13, 2008. Archived from the original on April 26, 2008. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- ^ "Google Groups". Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "News: links to Google Groups". Archived from the original on July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Who can force the moderators to obey the group charter?". Big-8.org. Archived from the original on August 4, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "How does a group change moderators?". Big-8.org. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Early Usenet Newsgroup Hierarchies". Livinginternet.com. October 25, 1990. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "How to Create a New Big-8 Newsgroup". Big-8.org. July 7, 2010. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ Donath, Judith (May 23, 2014). The Social Machine: Designs for Living Online. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262027014. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

Today, Usenet still exists, but it is an unsociable morass of spam, porn, and pirated software

- ^ "Unraveling the Internet's oldest and weirdest mystery". The Kernel. March 22, 2015. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

Groups filled with spam, massive fights took place against spammers and over what to do about the spam. People stopped using their email addresses in messages to avoid harvesting. People left the net.

- ^ "The American Way of Spam". Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

...many of the newsgroups have since been overrun with junk messages.

- ^ Microsoft Responds to the Evolution of Communities Archived September 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Announcement, undated. "Microsoft hitting 'unsubscribe' on newsgroups". CNET. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012., CNET, May 4, 2010.

- ^ Gregersen, Erik; Hosch, William L. (February 17, 2022). "newsgroup". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on April 28, 2023. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ "Usenet storage is more than 60 petabytes (60000 terabytes)". binsearch.info. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "usenet backup (uBackup)". wikiHow. Wikihow.com. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "Eweka 4446 Days Retention". Eweka.nl. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "Digital Millenium Copyright Act". Archived from the original on September 10, 2012.

- ^ "Cancel Messages FAQ". Archived from the original on February 15, 2008. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

...Until authenticated cancels catch on, there are no options to avoid forged cancels and allow unforged ones...

- ^ Microsoft knowledgebase article stating that many servers ignore cancel messages "Support.microsoft.com". Archived from the original on July 19, 2012.

- ^ "Microsoft Word - Surmacz.doc" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ ...every part of a Usenet post may be forged apart from the left most portion of the "Path:" header... "By-users.co.uk". Archived from the original on July 23, 2012.

- ^ "Better living through forgery". Newsgroup: news.admin.misc. June 10, 1995. Usenet: StUPidfuk01@uunet.uu.net. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Giganews Privacy Policy". Giganews.com. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Privacy Policy UsenetServer". Usenetserver.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ^ "Logging Policy". Aioe.org. June 9, 2005. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Quux.org". Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ LaQuey, Tracy (1990). The User's directory of computer networks. Digital Press. p. 386. ISBN 978-1555580476

- ^ "And So It Begins". Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ^ "History of the Internet, Chapter Three: History of Electronic Mail". Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ^ Hauben, Michael and Hauben, Ronda. "Netizens: On the History and Impact of Usenet and the Internet, On the Early Days of Usenet: The Roots of the Cooperative Online Culture Archived June 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine". First Monday vol. 3 num.August 8, 3 1998

- ^ Haddadi, H. (2006). "Network Traffic Inference Using Sampled Statistics Archived November 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine". University College London.

- ^ Horton, Mark (December 11, 1990). "Arachnet". Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ^ Huston, Geoff (1999). ISP survival guide: strategies for running a competitive ISP. Wiley. p. 439.

- ^ "Unix/Linux news servers". Newsreaders.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ Tim Berners-Lee (August 6, 1991). "WorldWideWeb: Summary". Newsgroup: alt.hypertext. Usenet: 6487@cernvax.cern.ch. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus. "What would you like to see most in minix?". Newsgroup: comp.os.minix. Usenet: 1991Aug25.205708.9541@klaava.Helsinki.FI. Archived from the original on October 27, 2006. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ^ Marc Andreessen (March 15, 1993). "NCSA Mosaic for X 0.10 available". Newsgroup: comp.windows.x. Usenet: MARCA.93Mar14225600@wintermute.ncsa.uiuc.edu. Archived from the original on June 16, 2006. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ^ Kaltenbach, Susan (December 2000). "The Evolution of the Online Discourse Community" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

Verb Doubling: Doubling a verb may change its semantics, Soundalike Slang: Punning jargon, The -P convention: A LISPy way to form questions, Overgeneralization: Standard abuses of grammar, Spoken Inarticulations: Sighing and <*sigh*>ing, Anthropomorphization: online components were named "Homunculi," daemons," etc., and there were also "confused" programs. Comparatives: Standard comparatives for design quality

- ^ Campbell, K. K. (October 1, 1994). "Chatting With Martha Siegel of the Internet's Infamous Canter & Siegel". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Archived from the original on November 25, 2007. Retrieved September 24, 2010.

- ^ Segan, Sascha (July 31, 2008). "R.I.P Usenet: 1980-2008". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ Cara Bonnett (May 17, 2010). "A Piece of Internet History". Duke Today. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ Andrew Orlowski (May 20, 2010). "Usenet's home shuts down today". The Register. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ ""Reports of Usenet's Death Are Greatly Exaggerated". Archived from the original on July 16, 2012.." TechCrunch. August 1, 2008. Retrieved on May 8, 2011.

- ^ "What Is Usenet". Top 10 Usenet. Archived from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "Top 100 text newsgroups by postings". NewsAdmin. Archived from the original on October 16, 2006. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Top 100 binary newsgroups by postings". NewsAdmin. Archived from the original on October 16, 2006. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Usenet Piracy". IP Arrow. Archived from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "Usenet Newsgroup Feed Size - NewsDemon Usenet Newsgroup Access".

- ^ Rosencrance, Lisa. "3 top ISPs to block access to sources of child porn". Archived from the original on July 22, 2012.. Computer World. June 8, 2008. Retrieved on April 30, 2009.

- ^ DeJean, David. "Usenet: Not Dead Yet." PC World. Tuesday October 7, 2008. "2". October 7, 2008. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2017.. Retrieved on April 30, 2009.

- ^ "ATT Announces Discontinuation of USENET Newsgroup Services". NewsDemon. June 9, 2009. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ^ Hu, Jim. ""AOL shutting down newsgroups". Archived from the original on July 23, 2012.." CNet. January 25, 2005. Retrieved on May 1, 2009.

- ^ "AOL Pulls Plug on Newsgroup Service". Betanews.com. January 25, 2005. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ Bode, Karl. "Verizon To Discontinue Newsgroups September 30". DSL Reports. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012.. DSLReports. August 31, 2009. Retrieved on October 24, 2009.

- ^ ""Verizon Newsgroup Service Has Been Discontinued". Archived from the original on September 21, 2012." Verizon Central Support. Retrieved on October 24, 2009.

- ^ Ukerna.ac.uk[dead link]

- ^ "Microsoft Responds to the Evolution of Communities". microsoft.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 2003. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ "AOL shutting down newsgroups". cnet.com/. January 25, 2005. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ "Verizon To Discontinue Newsgroups". dslreports.com. August 31, 2009. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ "The Comcast Newsgroups Service Discontinued". dslreports.com. September 16, 2008. Archived from the original on December 6, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Cox to Drop Free Usenet Service June 30th". Zeropaid.com. April 22, 2010. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ "Cox Discontinues Usenet, Starting In June". Geeknet, Inc. April 21, 2010. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ "Cox Communications and Atlantic Broadband Discontinue Usenet Access". thundernews.com. April 27, 2010. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ "How to obtain back news items". Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "How to obtain back news items (second posting)". Newsgroup: net.general. December 21, 1982. Archived from the original on January 29, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

message-id:bnews.spanky.138

- ^ "Distributed archiving of netnews". Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Archive of netnews". Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Re: Archive of netnews". Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Automatic access to archives". Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "keepnews – A Usenet news archival system". Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "YA News Archiver". Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "RFC usenet article archive program with keyword lookup". Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Looking for fulltext indexing software for archived news". Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Summary: search for fulltext indexing software for archived news". Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Asstr.org". Archived from the original on August 18, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ Segan, Sascha (July 31, 2008). "R.I.P Usenet: 1980–2008 – Usenet's Decline – Columns by PC Magazine". Pcmag.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ Strawbridge, Matthew (2006). Netiquette: Internet Etiquette in the Age of the Blog. Software Reference. p. 53. ISBN 978-0955461408

- ^ Cullen, Drew (February 12, 2001). "Google saves Deja.com Usenet service". The Register. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012.. The Register.

- ^ Wiseman, David. "Magi's NetNews Archive Involvement" Archived February 9, 2005, at archive.today, csd.uwo.ca.

- ^ Mieszkowski, Katharine. ""The Geeks Who Saved Usenet". Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.", archive.salon.com (January 7, 2002).

- ^ Feldman, Ian. "Usenet on a CD-ROM, no longer a fable". February 10, 1992. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012., "TidBITS" (February 10, 1992)

- ^ "Google Groups Archive Information". Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. (December 21, 2001)

- ^ Poulsen, Kevin (October 7, 2009). "Google's Abandoned Library of 700 Million Titles". Wired. Archived from the original on March 9, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ Braga, Matthew (February 13, 2015). "Google, a Search Company, Has Made Its Internet Archive Impossible to Search". Motherboard. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ Edwards, Douglas (2011). I'm Feeling Lucky: The Confessions of Google Employee Number 59. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 209–213. ISBN 978-0-547-41699-1.

- ^ "Google Groups ending support for Usenet - Google Groups Help". Google Support.

Further reading

[edit]- Bruce Jones (July 1, 1997). "USENET History mailing list archive covering 1990-1997". Archived from the original on May 7, 2019.

- Hauben, Michael; Hauben, Ronda; Truscott, Tom (April 27, 1997). Netizens: On the History and Impact of Usenet and the Internet (Perspectives). Wiley-IEEE Computer Society P. ISBN 978-0-8186-7706-9. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- Bryan Pfaffenberger (December 31, 1994). The USENET Book: Finding, Using, and Surviving Newsgroups on the Internet. Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-40978-9.

- Kate Gregory; Jim Mann; Tim Parker & Noel Estabrook (June 1995). Using Usenet Newsgroups. Que. ISBN 978-0-7897-0134-3.

- Mark Harrison (July 1995). The USENET Handbook (Nutshell Handbook). O'Reilly. ISBN 978-1-56592-101-6.

- Spencer, Henry; David Lawrence (January 1998). Managing Usenet. O'Reilly. ISBN 978-1-56592-198-6.

- Don Rittner (June 1997). Rittner's Field Guide to Usenet. MNS Publishing. ISBN 978-0-937666-50-0.

- Konstan, J.; Miller, B.; Maltz, D.; Herlocker, J.; Gordon, L.; Riedl, J. (March 1997). "GroupLens: applying collaborative filtering to Usenet news". Communications of the ACM. 40 (3): 77–87. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.377.1605. doi:10.1145/245108.245126. S2CID 15008577.

- Miller, B.; Riedl, J.; Konstan, J. (January 1997). Experiences with GroupLens: Making Usenet useful again (PDF). Proceedings of the 1997 Usenix Winter Technical Conference. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 6, 2006. Retrieved December 13, 2005.

- "20 Year Usenet Timeline". Archived from the original on January 5, 2007. Retrieved June 27, 2006.

- Schwartz, Randal (June 15, 2006). "Web 2.0, Meet Usenet 1.0". Linux Magazine. Archived from the original on February 16, 2007. Retrieved September 3, 2025.

- Kleiner, Dmytri; Wyrick, Brian (January 29, 2007). "InfoEnclosure 2.0". Archived from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

External links

[edit]- IETF working group USEFOR (USEnet article FORmat), tools.ietf.org

- A-News Archive: Early Usenet news articles: 1981 to 1982., quux.org

- "Netscan". Archived from the original on June 21, 2007. Social Accounting Reporting Tool

- Living Internet A comprehensive history of the Internet, including Usenet. livinginternet.com

- Usenet Glossary A comprehensive list of Usenet terminology

- Usenet free servers A list of free providers of Usenet server access

Usenet

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Core Principles

Usenet, a portmanteau of "users' network," constitutes a worldwide distributed discussion system comprising hierarchically organized collections of newsgroups for exchanging threaded messages and files among participants.[10] Initially implemented via the Unix-to-Unix Copy Protocol (UUCP) on dial-up connections, it enabled asynchronous communication across interconnected Unix systems as an accessible means for posting and retrieving articles beyond the scope of ARPANET's email lists.[11] Articles, the fundamental units of content, include headers specifying subjects, authors, dates, and references to prior messages, facilitating the formation of conversation threads that users navigate chronologically or topically.[12] At its core, Usenet embodies decentralization through a federated model of independent servers that exchange articles via peer-to-peer newsfeeds, eschewing any central authority or single point of control over content dissemination.[13] This propagation mechanism—wherein servers relay incoming articles to their configured peers—ensures broad replication and resilience against individual server failures, as no proprietary database or host dictates availability or moderation universally.[14] Newsgroups adhere to a hierarchical naming convention, such as comp.sys.mac for topics in Macintosh computing, which partitions discussions by broad categories (e.g., comp for computers) into subtopics, promoting topical focus while allowing alternative hierarchies for specialized communities.[11] Empirically, this structure contrasts with centralized client-server paradigms, like those in web-based forums, where a singular authority manages persistence and access; in Usenet, article visibility depends on feed policies and retention durations across servers, yielding potential inconsistencies such as delayed propagation or selective omissions by operators, yet fostering robustness through redundancy.[13] Threading relies on explicit reference headers linking replies to antecedents, enabling readers to reconstruct discussions without reliance on server-side indexing, a principle that underscores Usenet's emphasis on self-organizing, user-driven discourse over administered curation.[12]Key Components and Decentralized Nature

Usenet's core components comprise news servers responsible for storing articles and forwarding them across the network, newsreaders that provide user interfaces for accessing and posting to newsgroups, and news feeds that enable the transfer of articles between interconnected servers.[15][16] News servers operate independently, maintaining local repositories typically in directories like/var/spool/news, while newsreaders connect via protocols such as NNTP to retrieve content without direct server-to-server dependency for user access.[15]

The decentralized nature of Usenet arises from its peer-to-peer propagation model, where servers selectively subscribe to specific newsgroups and exchange articles through configured feeds rather than relying on a central hub.[15][17] This lack of a global authority or unified index means that article availability varies, with servers forming partial mirrors of the full corpus, and users pulling content from their local server, which may not hold all posts.[15] Feed policies, often defined using batch files (BAT files) in early implementations, dictate what articles are pushed to downstream peers, allowing operators to control volume and scope autonomously.[15]

This architecture has supported over 100,000 newsgroups historically, fostering resilience and autonomy but introducing challenges like inconsistent propagation delays—typically resolving within hours as articles disseminate via flooding algorithms—and variable retention periods determined by individual server storage policies.[18][16] Propagation relies on queued or immediate feeds, with delays stemming from network topology and operator configurations rather than centralized scheduling.[15]

Technical Architecture

Protocols and News Propagation

The Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP), defined in RFC 3977, serves as the primary application-layer protocol for distributing Usenet articles between news servers and facilitating client-server interactions.[19] Originally specified in RFC 977 in March 1986, NNTP enables efficient transmission over reliable full-duplex channels, supporting commands for posting articles, retrieving lists of newsgroups, and transferring articles via modes like IHAVE and SEND. Server-to-server feeds typically use NNTP over IP connections in modern implementations, replacing earlier UUCP-based batch transfers for real-time propagation.[20] Usenet employs a flood-fill propagation mechanism where articles are injected into the network at a local server and then disseminated to peering servers. Upon receipt of an article—identified uniquely by its Message-ID header—a server checks for duplicates before forwarding it to its peers, ensuring eventual consistency across the decentralized network without central coordination.[21] This process relies on server peering agreements, with articles pushed via NNTP feeds; propagation delays depend on network topology and peering density, often completing globally within hours.[22] Retention periods vary by server policy and content type: text articles are typically held for days to weeks, while binary content on commercial providers can persist for years, with some offering over 16 years (approximately 5,800+ days) as of 2025 to support archival access.[23] Usenet articles conform to a structured format outlined in RFC 1036, comprising headers and a body separated by a blank line. Essential headers include From (author), Newsgroups (target hierarchy), Subject, Date, Message-ID (unique identifier formatted as unique@domain), and Path (propagation trace with site names separated by '!'). Threading is maintained through References and In-Reply-To headers, which list Message-IDs of parent messages, allowing newsreaders to reconstruct discussions hierarchically.[24] [25] To mitigate spam, Usenet supports cancellation control messages, which instruct servers to remove specified articles by referencing their Message-ID. These are processed locally if authenticated—originally via approved sender lists or later cancel locks (e.g., cryptographic hashes)—and propagate similarly to regular articles, though adoption varies as some servers ignore unauthenticated cancels to prevent abuse. Empirical evidence from early spam incidents, such as the 1994 Canterbury Dreamware flood, demonstrates cancellations' role in rapid content removal, though incomplete propagation can leave remnants on distant servers.[26] [27]Newsgroups: Structure and Moderation

Newsgroups in Usenet are organized into hierarchical categories prefixed by topical domains, facilitating structured navigation across diverse discussions. The primary hierarchies, known as the Big Eight—comprising comp. (computing), humanities. (arts and literature), misc. (miscellaneous), news. (Usenet administration), rec. (recreation), sci. (science), soc. (social issues), and talk. (debate)—are managed by a volunteer Big-8 Management Board that oversees creation through formal proposals and community voting processes to ensure relevance and sustainability.[28][29] In contrast, alternative hierarchies such as alt. permit vote-free creation via control messages issued by any user, enabling rapid proliferation without centralized approval and reflecting Usenet's decentralized ethos, though this often resulted in fragmented or short-lived groups.[30] By the late 1990s, Usenet encompassed over 100,000 newsgroups across these and other hierarchies, driven by exponential growth in user participation, though active groups numbered in the tens of thousands.[31] Moderation operates on a spectrum, with the majority of newsgroups unmoderated, allowing direct propagation of posts from users to servers without intermediary review, which promotes immediacy and unrestricted exchange but exposes groups to spam, off-topic content, and abuse.[32] Moderated newsgroups, such as comp.risks (focused on computing safety incidents), route submissions via email to designated moderators who evaluate and approve posts for relevance and quality before propagation, aiming to maintain focused discourse and filter low-value contributions.[33] This approach yields benefits like reduced noise and higher signal-to-noise ratios, as evidenced by sustained participation in long-standing moderated groups, but introduces drawbacks including processing delays—sometimes days or weeks—and risks of moderator bias or overreach, potentially suppressing dissenting views under the guise of quality control.[34] Empirical observations from Usenet operators indicate that moderation demands ongoing volunteer effort, with bottlenecks emerging in high-volume groups, while unmoderated forums rely on community self-policing through norms like follow-ups and critiques.[35] Newsgroup lifecycle governance occurs via the control pseudo-newsgroup, where control messages propose creations, renamings, or deletions, processed by server software to issue commands like "newgroup" or "rmgroup." For Big Eight hierarchies, these proposals undergo board-vetted voting requiring majority support from discussants, enforcing communal consensus without mandatory server compliance, as propagation depends on individual site policies.[36] Alternative hierarchies bypass such votes, allowing forking through unilateral control messages, which proliferated groups but also sparked "newsgroup wars" over legitimacy and carriage disputes among backbone providers. This model underscores Usenet's lack of central authority, with site administrators retaining autonomy to carry or reject groups based on local resources and community input, preventing any single entity from dictating global structure.[37]Access Tools: Newsreaders and Servers

Usenet access requires specialized client software known as newsreaders, which connect to servers via the Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP) to retrieve and post articles.[38] Command-line newsreaders such as tin and nn provide efficient, text-based interfaces suitable for Unix-like systems, enabling local or remote reading of newsgroups with features like threaded article navigation and header caching for speed.[39] [40] Graphical user interface (GUI) newsreaders, including integrations in email clients like Mozilla Thunderbird, offer point-and-click usability for subscribing to newsgroups, viewing threads, and composing posts, making them accessible to users less familiar with terminal commands.[41] A key feature distinguishing traditional newsreaders from web-based alternatives is the implementation of scoring filters, which allow users to assign numerical scores to articles based on criteria such as author, subject keywords, or posting patterns, thereby personalizing feeds by promoting or hiding content algorithmically.[42] This enables power users to manage high-volume discussions effectively, reducing noise in unmoderated groups, whereas web interfaces often prioritize simplicity over such granular control, potentially limiting customization for advanced filtering needs.[43] Usenet servers store and propagate articles, with access historically provided through internet service providers (ISPs) offering free NNTP feeds, though retention periods were typically limited to days or weeks.[44] Following the 2000s, many ISPs discontinued complimentary Usenet services due to escalating bandwidth and storage costs driven by binary content proliferation, prompting a shift toward commercial providers.[44] Paid servers, such as those from Newshosting, maintain extensive binary retention exceeding 6,200 days as of October 2025, ensuring availability of historical archives via subscription-based access with enhanced completion rates and speeds.[45] Users connect newsreaders to these servers using credentials, bypassing ISP limitations for reliable, high-retention Usenet interaction.[44]Handling Binary and Multimedia Content

Usenet, designed primarily for text-based articles, requires binary and multimedia files to be encoded into text format for transmission via the NNTP protocol. Early methods included uuencode, which converts binary data to printable ASCII characters but introduces approximately 35% overhead due to escaping non-ASCII bytes.[46] This encoding ensures compatibility with text-only servers, though it increases transmission size and processing demands.[47] The yEnc scheme, introduced in the late 1990s, became the dominant encoding for binaries by offering superior efficiency, with encoded data expanding to only 1-2% above the original binary size.[46] yEnc achieves this through minimal escaping and CRC-32 checksums for error detection, reducing bandwidth usage and decoding time compared to uuencode or MIME base64, which can add 33% overhead.[48] Large files are typically split into multiple articles, each encoded separately and posted sequentially in binary newsgroups like those under alt.binaries hierarchies.[48] To facilitate retrieval of multipart binaries scattered across articles, NZB index files—XML documents containing message-ID pointers and metadata—enable newsreaders to automate downloading and reassembly.[49] Users generate NZBs from indexers that scan newsgroup headers, allowing efficient fetching without manual header downloads.[50] Retention policies differ markedly between text and binary content due to storage and bandwidth constraints. Text articles, being smaller, often retain for thousands of days on many servers, while binaries demand more resources, leading providers to prioritize shorter or tiered retention.[51] In 2025, premium providers maintain binary retention exceeding 5,000 days (over 13 years), supported by extensive mirroring across backbones.[52] Free or ISP servers typically offer days to weeks for binaries versus longer for text, reflecting cost-based trade-offs.[53] The high volume of binary traffic prompted server policies strictly segregating content: binaries are confined to designated groups to prevent flooding text discussions, as disguised binary posts inflate sizes and enable spam proliferation by evading filters.[54] This separation mitigates bandwidth overload, with many operators enforcing rules or automated removal of off-topic binaries in text hierarchies to preserve usability.[51]Historical Development

Origins in ARPANET-Era Experimentation (1979–1985)

Usenet originated as an experimental distributed discussion system designed to circumvent the bandwidth and policy restrictions of the ARPANET, which prohibited non-research communications and favored dedicated leased lines unsuitable for many academic sites. In late 1979, graduate students Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis at Duke University conceived the idea of leveraging the Unix-to-Unix Copy (UUCP) protocol—a store-and-forward mechanism using dial-up phone lines—to exchange files and messages between Unix systems, enabling asynchronous, low-cost information sharing among universities lacking ARPANET access.[55][56][57] The initial implementation involved shell scripts written by Steve Bellovin at the University of North Carolina (UNC), which connected Duke and UNC for the first exchanges; the earliest documented article, posted in December 1979, discussed Unix shell programming techniques. By early 1980, these scripts evolved into compiled software dubbed "A News," developed by Steve Daniel and distributed publicly to handle growing traffic on UUCP links. This volunteer-driven effort, without central funding or administration, relied on site operators manually configuring batch transfers via modems, typically nightly, to propagate articles across connected hosts.[58][55] Early adoption was fueled by the proliferation of Unix systems in academia and research labs, expanding from two initial sites (Duke and UNC) to about 15 by the end of 1980 and 150 by 1981, as universities like the University of California, Berkeley, and Bell Labs joined via UUCP feeds. By 1982, participation reached around 400 sites, and empirical logs indicate hundreds more by 1985, sustained by organic propagation without formal governance—operators shared software updates and moderated content locally to manage volume. This decentralized model emphasized resilience over speed, with articles batched into files for transfer, reflecting first-principles adaptations to constrained telephony infrastructure rather than real-time networking.[57][59][17]Expansion and Institutional Adoption (1986–1993)

In 1983, B News software, developed by Mark Horton and Matt Glickman at Bell Labs, superseded the original A News implementation, introducing improved article threading, storage efficiency, and batching capabilities that facilitated larger-scale propagation over UUCP networks.[9][60] This upgrade addressed limitations in handling growing volumes of posts, enabling Usenet to scale beyond initial university sites.[58] The introduction of the Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP) in March 1986, as specified in RFC 977, marked a pivotal shift to TCP/IP-based transmission, allowing direct integration with ARPANET and emerging Internet infrastructure.[58][61] NNTP supported client-server access to remote news servers, reducing reliance on batch file transfers and enabling real-time querying, which accelerated adoption among academic institutions connected via NSFNET.[62] By leveraging NSFNET's backbone, Usenet expanded from hundreds of sites in the early 1980s to widespread institutional use, with propagation efficiency improving causal connectivity across research networks.[57] The alt.* hierarchy emerged in the late 1980s, initiated through alternative creation processes like those for alt.sex, providing a decentralized counterpoint to moderated hierarchies and fostering unmoderated discussions on diverse topics.[63] Commercialization began with providers like PSINet offering paid Usenet feeds by 1990, including dial-up access that extended availability beyond academia.[64] Concurrently, the practice of posting Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) files gained traction in the late 1980s, standardizing information dissemination and reducing repetitive queries in high-traffic groups.[65] These developments underscored Usenet's transition to a robust, multi-stakeholder system by 1993.[66]Peak Usage and "Eternal September" (1994–1999)

During the mid-1990s, Usenet experienced its zenith of participation, fueled by the expansion of commercial internet service providers that integrated gateways to the network. America Online (AOL), which began offering Usenet access in September 1993, saw its subscriber base surge from approximately 2 million in 1993 to over 5 million by 1995, channeling a massive wave of non-technical users into Usenet groups and amplifying traffic volumes.[67] Similarly, Microsoft Network (MSN) and other dial-up services introduced gateways, broadening access beyond academic and technical enclaves to mainstream audiences seeking discussion forums on diverse topics from computing to hobbies.[68] This era solidified the "Eternal September," a term originating from the perpetual influx of novices that eroded Usenet's self-policing culture, as the one-time annual onboarding of university freshmen—accustomed to learning etiquette via frequently asked questions (FAQs) and netiquette—gave way to unending arrivals lacking such preparation. By 1994–1995, the phenomenon persisted, with veterans reporting heightened disruption from off-topic posts, flame wars, and failure to adhere to group norms, transforming transient September overloads into a chronic state.[67] [69] The decentralization of Usenet, reliant on voluntary server peering, buckled under this scale, as exponential message propagation strained bandwidth and encouraged excessive crossposting—early harbingers of spam—without centralized moderation to curb abuse.[70] Participation peaked with an estimated several million regular readers worldwide by the late 1990s, coinciding with the proliferation of over 40,000 newsgroups by mid-decade, many in the alt.* hierarchy spawned by unmoderated creation scripts.[5] Tools like kill files, which allowed users to programmatically filter authors, subjects, or keywords, gained widespread adoption as a pragmatic response to noise from unskilled posters, enabling experienced users to curate feeds amid the deluge.[69] Web-based interfaces, such as Deja News launched in 1995, further democratized access by enabling browser-based searching of archives without native newsreader software, inadvertently commodifying discussions while exposing them to broader scrutiny and off-topic incursions.[71] This accessibility, however, exacerbated cultural fractures, as commercial incentives prioritized volume over the meritocratic ethos that had sustained Usenet's earlier coherence.[72]Decline and Fragmentation (2000–2010)