Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Internet access

View on WikipediaThis article needs to be updated. The reason given is: Many statistics are outdated; the article makes little mention of modern applications of Internet access (e.g. video streaming). (June 2023) |

| Internet |

|---|

|

|

|

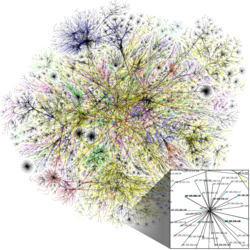

Internet access is a facility or service that provides connectivity for a computer, a computer network, or other network device to the Internet, and for individuals or organizations to access or use applications such as email and the World Wide Web. Internet access is offered for sale by an international hierarchy of Internet service providers (ISPs) using various networking technologies. At the retail level, many organizations, including municipal entities, also provide cost-free access to the general public. Types of connections range from fixed-line cable (such as DSL and fiber optic) to mobile (via cellular) and satellite.[1]

The availability of Internet access to the general public began with the commercialization of the early Internet in the early 1990s, and has grown with the availability of useful applications, such as the World Wide Web. In 1995, only 0.04 percent of the world's population had access, with well over half of those living in the United States [2] and consumer use was through dial-up. By the first decade of the 21st century, many consumers in developed nations used faster broadband technology. By 2014, 41 percent of the world's population had access,[3] broadband was almost ubiquitous worldwide, and global average connection speeds exceeded one megabit per second.[4]

History

[edit]The Internet developed from the ARPANET, which was funded by the US government to support projects within the government, at universities and research laboratories in the US, but grew over time to include most of the world's large universities and the research arms of many technology companies.[5][6][7] Use by a wider audience only came in 1995 when restrictions on the use of the Internet to carry commercial traffic were lifted.[8]

In the early to mid-1980s, most Internet access was from personal computers and workstations directly connected to local area networks (LANs) or from dial-up connections using modems and analog telephone lines. LANs typically operated at 10 Mbit/s while modem data-rates grew from 1200 bit/s in the early 1980s to 56 kbit/s by the late 1990s. Initially, dial-up connections were made from terminals or computers running terminal-emulation software to terminal servers on LANs. These dial-up connections did not support end-to-end use of the Internet protocols and only provided terminal-to-host connections. The introduction of network access servers supporting the Serial Line Internet Protocol (SLIP) and later the point-to-point protocol (PPP) extended the Internet protocols and made the full range of Internet services available to dial-up users; although slower, due to the lower data rates available using dial-up.

An important factor in the rapid rise of Internet access speed has been advances in MOSFET (MOS transistor) technology.[9] The MOSFET invented at Bell Labs between 1955 and 1960 following Frosch and Derick discoveries,[10][11][12][13][14][15] is the building block of the Internet telecommunications networks.[16][17] The laser, originally demonstrated by Charles H. Townes and Arthur Leonard Schawlow in 1960, was adopted for MOS light-wave systems around 1980, which led to exponential growth of Internet bandwidth. Continuous MOSFET scaling has since led to online bandwidth doubling every 18 months (Edholm's law, which is related to Moore's law), with the bandwidths of telecommunications networks rising from bits per second to terabits per second.[9]

Broadband Internet access, often shortened to just broadband, is simply defined as "Internet access that is always on, and faster than the traditional dial-up access"[18][19] and so covers a wide range of technologies. The core of these broadband Internet technologies are complementary MOS (CMOS) digital circuits,[20][21] the speed capabilities of which were extended with innovative design techniques.[21] Broadband connections are typically made using a computer's built in Ethernet networking capabilities, or by using a NIC expansion card.

Most broadband services provide a continuous "always on" connection; there is no dial-in process required, and it does not interfere with voice use of phone lines.[22] Broadband provides improved access to Internet services such as:

- Faster World Wide Web browsing

- Faster downloading of documents, photographs, videos, and other large files

- Telephony, radio, television, and videoconferencing

- Virtual private networks and remote system administration

- Online gaming, especially massively multiplayer online role-playing games which are interaction-intensive

In the 1990s, the National Information Infrastructure initiative in the U.S. made broadband Internet access a public policy issue.[23] In 2000, most Internet access to homes was provided using dial-up, while many businesses and schools were using broadband connections. In 2000 there were just under 150 million dial-up subscriptions in the 34 OECD countries[24] and fewer than 20 million broadband subscriptions. By 2004, broadband had grown and dial-up had declined so that the number of subscriptions were roughly equal at 130 million each. In 2010, in the OECD countries, over 90% of the Internet access subscriptions used broadband, broadband had grown to more than 300 million subscriptions, and dial-up subscriptions had declined to fewer than 30 million.[25]

The broadband technologies in widest use are of digital subscriber line (DSL), ADSL, and cable Internet access. Newer technologies include VDSL and optical fiber extended closer to the subscriber in both telephone and cable plants. Fiber-optic communication, while only recently being used in premises and to the curb schemes, has played a crucial role in enabling broadband Internet access by making transmission of information at very high data rates over longer distances much more cost-effective than copper wire technology.

In areas not served by ADSL or cable, some community organizations and local governments are installing Wi-Fi networks. Wireless, satellite, and microwave Internet are often used in rural, undeveloped, or other hard to serve areas where wired Internet is not readily available.

Newer technologies being deployed for fixed (stationary) and mobile broadband access include WiMAX, LTE, and fixed wireless.

Starting in roughly 2006, mobile broadband access is increasingly available at the consumer level using "3G" and "4G" technologies such as HSPA, EV-DO, HSPA+, and LTE.

Availability

[edit]

In addition to access from home, school, and the workplace Internet access may be available from public places such as libraries and Internet cafés, where computers with Internet connections are available. Some libraries provide stations for physically connecting users' laptops to LANs.

Wireless Internet access points are available in public places such as airport halls, in some cases just for brief use while standing. Some access points may also provide coin-operated computers. Various terms are used, such as "public Internet kiosk", "public access terminal", and "Web payphone". Many hotels also have public terminals, usually fee based.

Coffee shops, shopping malls, and other venues increasingly offer wireless access to computer networks, referred to as hotspots, for users who bring their own wireless-enabled devices such as a laptop or PDA. These services may be free to all, free to customers only, or fee-based. A Wi-Fi hotspot need not be limited to a confined location since multiple ones combined can cover a whole campus or park, or even an entire city can be enabled.

Additionally, mobile broadband access allows smartphones and other digital devices to connect to the Internet from any location from which a mobile phone call can be made, subject to the capabilities of that mobile network.

Speed

[edit]The bit rates for dial-up modems range from as little as 110 bit/s in the late 1950s, to a maximum of from 33 to 64 kbit/s (V.90 and V.92) in the late 1990s. Dial-up connections generally require the dedicated use of a telephone line. Data compression can boost the effective bit rate for a dial-up modem connection from 220 (V.42bis) to 320 (V.44) kbit/s.[26] However, the effectiveness of data compression is quite variable, depending on the type of data being sent, the condition of the telephone line, and a number of other factors. In reality, the overall data rate rarely exceeds 150 kbit/s.[27]

Broadband technologies supply considerably higher bit rates than dial-up, generally without disrupting regular telephone use. Various minimum data rates and maximum latencies have been used in definitions of broadband, ranging from 64 kbit/s up to 4.0 Mbit/s.[28] In 1988 the CCITT standards body defined "broadband service" as requiring transmission channels capable of supporting bit rates greater than the primary rate which ranged from about 1.5 to 2 Mbit/s.[29] A 2006 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report defined broadband as having download data transfer rates equal to or faster than 256 kbit/s.[30] And in 2015 the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) defined "Basic Broadband" as data transmission speeds of at least 25 Mbit/s downstream (from the Internet to the user's computer) and 3 Mbit/s upstream (from the user's computer to the Internet).[31] The trend is to raise the threshold of the broadband definition as higher data rate services become available.[32]

The higher data rate dial-up modems and many broadband services are "asymmetric"—supporting much higher data rates for download (toward the user) than for upload (toward the Internet).

Data rates, including those given in this article, are usually defined and advertised in terms of the maximum or peak download rate. In practice, these maximum data rates are not always reliably available to the customer.[33] Actual end-to-end data rates can be lower due to a number of factors.[34] In late June 2016, internet connection speeds averaged about 6 Mbit/s globally.[35] Physical link quality can vary with distance and for wireless access with terrain, weather, building construction, antenna placement, and interference from other radio sources. Network bottlenecks may exist at points anywhere on the path from the end-user to the remote server or service being used and not just on the first or last link providing Internet access to the end-user.

Network congestion

[edit]Users may share access over a common network infrastructure. Since most users do not use their full connection capacity all of the time, this aggregation strategy (known as contended service) usually works well, and users can burst to their full data rate at least for brief periods. However, peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing and high-quality streaming video can require high data-rates for extended periods, which violates these assumptions and can cause a service to become oversubscribed, resulting in congestion and poor performance. The TCP protocol includes flow-control mechanisms that automatically throttle back on the bandwidth being used during periods of network congestion. This is fair in the sense that all users who experience congestion receive less bandwidth, but it can be frustrating for customers and a major problem for ISPs. In some cases, the amount of bandwidth actually available may fall below the threshold required to support a particular service such as video conferencing or streaming live video–effectively making the service unavailable.

When traffic is particularly heavy, an ISP can deliberately throttle back the bandwidth available to classes of users or for particular services. This is known as traffic shaping and careful use can ensure a better quality of service for time critical services even on extremely busy networks. However, overuse can lead to concerns about fairness and network neutrality or even charges of censorship, when some types of traffic are severely or completely blocked.

Outages

[edit]An Internet blackout or outage can be caused by local signaling interruptions. Disruptions of submarine communications cables may cause blackouts or slowdowns to large areas, such as in the 2008 submarine cable disruption. Less-developed countries are more vulnerable due to a small number of high-capacity links. Land cables are also vulnerable, as in 2011 when a woman digging for scrap metal severed most connectivity for the nation of Armenia.[36] Internet blackouts affecting almost entire countries can be achieved by governments as a form of Internet censorship, as in the blockage of the Internet in Egypt, whereby approximately 93%[37] of networks were without access in 2011 in an attempt to stop mobilization for anti-government protests.[38]

On April 25, 1997, due to a combination of human error and a software bug, an incorrect routing table at MAI Network Service (a Virginia Internet service provider) propagated across backbone routers and caused major disruption to Internet traffic for a few hours.[39]

Technologies

[edit]When the Internet is accessed using a modem, digital data is converted to analog for transmission over analog networks such as the telephone and cable networks.[22] A computer or other device accessing the Internet would either be connected directly to a modem that communicates with an Internet service provider (ISP) or the modem's Internet connection would be shared via a LAN which provides access in a limited area such as a home, school, computer laboratory, or office building.

Although a connection to a LAN may provide very high data-rates within the LAN, actual Internet access speed is limited by the upstream link to the ISP. LANs may be wired or wireless. Ethernet over twisted pair cabling and Wi-Fi are the two most common technologies used to build LANs today, but ARCNET, Token Ring, LocalTalk, FDDI, and other technologies were used in the past.

Ethernet is the name of the IEEE 802.3 standard for physical LAN communication[40] and Wi-Fi is a trade name for a wireless local area network (WLAN) that uses one of the IEEE 802.11 standards.[41] Ethernet cables are interconnected via switches & routers. Wi-Fi networks are built using one or more wireless antenna called access points.

Many "modems" (cable modems, DSL gateways or Optical Network Terminals (ONTs)) provide the additional functionality to host a LAN so most Internet access today is through a LAN such as that created by a WiFi router connected to a modem or a combo modem router,[citation needed] often a very small LAN with just one or two devices attached. And while LANs are an important form of Internet access, this raises the question of how and at what data rate the LAN itself is connected to the rest of the global Internet. The technologies described below are used to make these connections, or in other words, how customers' modems (Customer-premises equipment) are most often connected to internet service providers (ISPs).

Dial-up technologies

[edit]Dial-up access

[edit]Dial-up Internet access uses a modem and a phone call placed over the public switched telephone network (PSTN) to connect to a pool of modems operated by an ISP. The modem converts a computer's digital signal into an analog signal that travels over a phone line's local loop until it reaches a telephone company's switching facilities or central office (CO) where it is switched to another phone line that connects to another modem at the remote end of the connection.[42]

Operating on a single channel, a dial-up connection monopolizes the phone line and is one of the slowest methods of accessing the Internet. Dial-up is often the only form of Internet access available in rural areas as it requires no new infrastructure beyond the already existing telephone network, to connect to the Internet. Typically, dial-up connections do not exceed a speed of 56 kbit/s, as they are primarily made using modems that operate at a maximum data rate of 56 kbit/s downstream (towards the end user) and 34 or 48 kbit/s upstream (toward the global Internet).[22]

Multilink dial-up

[edit]Multilink dial-up provides increased bandwidth by channel bonding multiple dial-up connections and accessing them as a single data channel.[43] It requires two or more modems, phone lines, and dial-up accounts, as well as an ISP that supports multilinking – and of course any line and data charges are also doubled. This inverse multiplexing option was briefly popular with some high-end users before ISDN, DSL and other technologies became available. Diamond and other vendors created special modems to support multilinking.[44]

Hardwired broadband access

[edit]The term broadband includes a broad range of technologies, all of which provide higher data rate access to the Internet. The following technologies use wires or cables in contrast to wireless broadband described later.

Integrated Services Digital Network

[edit]Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN) is a switched telephone service capable of transporting voice and digital data, and is one of the oldest Internet access methods. ISDN has been used for voice, video conferencing, and broadband data applications. ISDN was very popular in Europe, but less common in North America. Its use peaked in the late 1990s before the availability of DSL and cable modem technologies.[45]

Basic rate ISDN, known as ISDN-BRI, has two 64 kbit/s "bearer" or "B" channels. These channels can be used separately for voice or data calls or bonded together to provide a 128 kbit/s service. Multiple ISDN-BRI lines can be bonded together to provide data rates above 128 kbit/s. Primary rate ISDN, known as ISDN-PRI, has 23 bearer channels (64 kbit/s each) for a combined data rate of 1.5 Mbit/s (US standard). An ISDN E1 (European standard) line has 30 bearer channels and a combined data rate of 1.9 Mbit/s. ISDN has been replaced by DSL technology,[46] and it required special telephone switches at the service provider.[47]

Leased lines

[edit]Leased lines are dedicated lines used primarily by ISPs, business, and other large enterprises to connect LANs and campus networks to the Internet using the existing infrastructure of the public telephone network or other providers. Delivered using wire, optical fiber, and radio, leased lines are used to provide Internet access directly as well as the building blocks from which several other forms of Internet access are created.[48]

T-carrier technology[49] dates to 1957 and provides data rates that range from 56 and 64 kbit/s (DS0) to 1.5 Mbit/s (DS1 or T1), to 45 Mbit/s (DS3 or T3).[50] A T1 line carries 24 voice or data channels (24 DS0s), so customers may use some channels for data and others for voice traffic or use all 24 channels for clear channel data. A DS3 (T3) line carries 28 DS1 (T1) channels. Fractional T1 lines are also available in multiples of a DS0 to provide data rates between 56 and 1500 kbit/s. T-carrier lines require special termination equipment such as Data service units[51][52][53] that may be separate from or integrated into a router or switch and which may be purchased or leased from an ISP.[54] In Japan the equivalent standard is J1/J3. In Europe, a slightly different standard, E-carrier, provides 32 user channels (64 kbit/s) on an E1 (2.0 Mbit/s) and 512 user channels or 16 E1s on an E3 (34.4 Mbit/s).

Synchronous Optical Networking (SONET, in the U.S. and Canada) and Synchronous Digital Hierarchy (SDH, in the rest of the world)[49] are the standard multiplexing protocols used to carry high-data-rate digital bit-streams over optical fiber using lasers or highly coherent light from light-emitting diodes (LEDs). At lower transmission rates data can also be transferred via an electrical interface. The basic unit of framing is an OC-3c (optical) or STS-3c (electrical) which carries 155.520 Mbit/s. Thus an OC-3c will carry three OC-1 (51.84 Mbit/s) payloads each of which has enough capacity to include a full DS3. Higher data rates are delivered in OC-3c multiples of four providing OC-12c (622.080 Mbit/s), OC-48c (2.488 Gbit/s), OC-192c (9.953 Gbit/s), and OC-768c (39.813 Gbit/s). The "c" at the end of the OC labels stands for "concatenated" and indicates a single data stream rather than several multiplexed data streams.[48] Optical transport network (OTN) may be used instead of SONET[55] for higher data transmission speeds of up to 400 Gbit/s per OTN channel.

The 1, 10, 40, and 100 Gigabit Ethernet IEEE standards (802.3) allow digital data to be delivered over copper wiring at distances to 100 m and over optical fiber at distances to 40 km.[56]

Cable Internet access

[edit]Cable Internet provides access using a cable modem on hybrid fiber coaxial (HFC) wiring originally developed to carry television signals. Either fiber-optic or coaxial copper cable may connect a node to a customer's location at a connection known as a cable drop. Using a cable modem termination system, all nodes for cable subscribers in a neighborhood connect to a cable company's central office, known as the "head end." The cable company then connects to the Internet using a variety of means – usually fiber optic cable or digital satellite and microwave transmissions.[57] Like DSL, broadband cable provides a continuous connection with an ISP.

Downstream, the direction toward the user, bit rates can be as much as 1000 Mbit/s in some countries, with the use of DOCSIS 3.1. Upstream traffic, originating at the user, ranges from 384 kbit/s to more than 50 Mbit/s. DOCSIS 4.0 promises up to 10 Gbit/s downstream and 6 Gbit/s upstream, however this technology is yet to have been implemented in real-world usage. Broadband cable access tends to service fewer business customers because existing television cable networks tend to service residential buildings; commercial buildings do not always include wiring for coaxial cable networks.[58] In addition, because broadband cable subscribers share the same local line, communications may be intercepted by neighboring subscribers. Cable networks regularly provide encryption schemes for data traveling to and from customers, but these schemes may be thwarted.[57]

Digital subscriber line (DSL, ADSL, SDSL, and VDSL)

[edit]Digital subscriber line (DSL) service provides a connection to the Internet through the telephone network. Unlike dial-up, DSL can operate using a single phone line without preventing normal use of the telephone line for voice phone calls. DSL uses the high frequencies, while the low (audible) frequencies of the line are left free for regular telephone communication.[22] These frequency bands are subsequently separated by filters installed at the customer's premises.

DSL originally stood for "digital subscriber loop". In telecommunications marketing, the term digital subscriber line is widely understood to mean asymmetric digital subscriber line (ADSL), the most commonly installed variety of DSL. The data throughput of consumer DSL services typically ranges from 256 kbit/s to 20 Mbit/s in the direction to the customer (downstream), depending on DSL technology, line conditions, and service-level implementation. In ADSL, the data throughput in the upstream direction, (i.e., in the direction to the service provider) is lower than that in the downstream direction (i.e. to the customer), hence the designation of asymmetric.[59] With a symmetric digital subscriber line (SDSL), the downstream and upstream data rates are equal.[60]

Very-high-bit-rate digital subscriber line (VDSL or VHDSL, ITU G.993.1)[61] is a digital subscriber line (DSL) standard approved in 2001 that provides data rates up to 52 Mbit/s downstream and 16 Mbit/s upstream over copper wires[62] and up to 85 Mbit/s down- and upstream on coaxial cable.[63] VDSL is capable of supporting applications such as high-definition television, as well as telephone services (voice over IP) and general Internet access, over a single physical connection.

VDSL2 (ITU-T G.993.2) is a second-generation version and an enhancement of VDSL.[64] Approved in February 2006, it is able to provide data rates exceeding 100 Mbit/s simultaneously in both the upstream and downstream directions. However, the maximum data rate is achieved at a range of about 300 meters and performance degrades as distance and loop attenuation increases.

DSL Rings

[edit]DSL Rings (DSLR) or Bonded DSL Rings is a ring topology that uses DSL technology over existing copper telephone wires to provide data rates of up to 400 Mbit/s.[65]

Fiber to the home

[edit]Fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) is one member of the Fiber-to-the-x (FTTx) family that includes Fiber-to-the-building or basement (FTTB), Fiber-to-the-premises (FTTP), Fiber-to-the-desk (FTTD), Fiber-to-the-curb (FTTC), and Fiber-to-the-node (FTTN).[66] These methods all bring data closer to the end user on optical fibers. The differences between the methods have mostly to do with just how close to the end user the delivery on fiber comes. All of these delivery methods are similar in function and architecture to hybrid fiber-coaxial (HFC) systems used to provide cable Internet access. Fiber internet connections to customers are either AON (Active optical network) or more commonly PON (Passive optical network). Examples of fiber optic internet access standards are G.984 (GPON, G-PON) and 10G-PON (XG-PON). ISPs may instead use Metro Ethernet as a replacement for T1 and Frame Relay lines[67] for corporate and institutional customers,[68] or offer carrier-grade Ethernet.[69] Dedicated internet access (DIA) in which the bandwidth is not shared among customers, can be offered over PON fiber optic networks.[70]

The use of optical fiber offers much higher data rates over relatively longer distances. Most high-capacity Internet and cable television backbones already use fiber optic technology, with data switched to other technologies (DSL, cable, LTE) for final delivery to customers.[71] Fiber optic is immune to electromagnetic interference.[72]

In 2010, Australia began rolling out its National Broadband Network across the country using fiber-optic cables to 93 percent of Australian homes, schools, and businesses.[73] The project was abandoned by the subsequent LNP government, in favor of a hybrid FTTN design, which turned out to be more expensive and introduced delays. Similar efforts are underway in Italy, Canada, India, and many other countries (see Fiber to the premises by country).[74][75][76][77]

Power-line Internet

[edit]Power-line Internet, also known as Broadband over power lines (BPL), carries Internet data on a conductor that is also used for electric power transmission.[78] Because of the extensive power line infrastructure already in place, this technology can provide people in rural and low population areas access to the Internet with little cost in terms of new transmission equipment, cables, or wires. Data rates are asymmetric and generally range from 256 kbit/s to 2.7 Mbit/s.[79]

Because these systems use parts of the radio spectrum allocated to other over-the-air communication services, interference between the services is a limiting factor in the introduction of power-line Internet systems. The IEEE P1901 standard specifies that all power-line protocols must detect existing usage and avoid interfering with it.[79]

Power-line Internet has developed faster in Europe than in the U.S. due to a historical difference in power system design philosophies. Data signals cannot pass through the step-down transformers used and so a repeater must be installed on each transformer.[79] In the U.S. a transformer serves a small cluster of from one to a few houses. In Europe, it is more common for a somewhat larger transformer to service larger clusters of from 10 to 100 houses. Thus a typical U.S. city requires an order of magnitude more repeaters than a comparable European city.[80]

ATM and Frame Relay

[edit]Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM) and Frame Relay are wide-area networking standards that can be used to provide Internet access directly[50] or as building blocks of other access technologies. For example, many DSL implementations use an ATM layer over the low-level bitstream layer to enable a number of different technologies over the same link. Customer LANs are typically connected to an ATM switch or a Frame Relay node using leased lines at a wide range of data rates.[81][82]

While still widely used, with the advent of Ethernet over optical fiber, MPLS, VPNs and broadband services such as cable modem and DSL, ATM and Frame Relay no longer play the prominent role they once did.

Wireless broadband access

[edit]Wireless broadband is used to provide both fixed and mobile Internet access with the following technologies.

Satellite broadband

[edit]

Satellite Internet access provides fixed, portable, and mobile Internet access.[83] Data rates range from 2 kbit/s to 1 Gbit/s downstream and from 2 kbit/s to 10 Mbit/s upstream. In the northern hemisphere, satellite antenna dishes require a clear line of sight to the southern sky, due to the equatorial position of all geostationary satellites. In the southern hemisphere, this situation is reversed, and dishes are pointed north.[84][85] Service can be adversely affected by moisture, rain, and snow (known as rain fade).[84][85][86] The system requires a carefully aimed directional antenna.[85]

Satellites in geostationary Earth orbit (GEO) operate in a fixed position 35,786 km (22,236 mi) above the Earth's equator. At the speed of light (about 300,000 km/s or 186,000 miles per second), it takes a quarter of a second for a radio signal to travel from the Earth to the satellite and back. When other switching and routing delays are added and the delays are doubled to allow for a full round-trip transmission, the total delay can be 0.75 to 1.25 seconds. This latency is large when compared to other forms of Internet access with typical latencies that range from 0.015 to 0.2 seconds. Long latencies negatively affect some applications that require real-time response, particularly online games, voice over IP, and remote control devices.[87][88] TCP tuning and TCP acceleration techniques can mitigate some of these problems. GEO satellites do not cover the Earth's polar regions.[84] HughesNet, Exede, AT&T and Dish Network have GEO systems.[89][90][91][92]

Satellite internet constellations in low Earth orbit (LEO, below 2,000 km or 1,243 miles) and medium Earth orbit (MEO, between 2,000 and 35,786 km or 1,243 and 22,236 miles) operate at lower altitudes, and their satellites are not fixed in their position above the Earth. Because they operate at a lower altitude, more satellites and launch vehicles are needed for worldwide coverage. This makes the initial required investment very large which initially caused OneWeb and Iridium to declare bankruptcy. However, their lower altitudes allow lower latencies and higher speeds which make real-time interactive Internet applications more feasible. LEO systems include Globalstar, Starlink, OneWeb and Iridium. The O3b constellation is a medium Earth-orbit system with a latency of 125 ms. COMMStellation™ is a LEO system, scheduled for launch in 2015,[needs update] that is expected to have a latency of just 7 ms.

Mobile broadband

[edit]

Mobile broadband is the marketing term for wireless Internet access delivered through mobile phone towers (cellular networks) to computers, mobile phones (called "cell phones" in North America and South Africa, and "hand phones" in Asia), and other digital devices using portable modems. Some mobile services allow more than one device to be connected to the Internet using a single cellular connection using a process called tethering. The modem may be built into laptop computers, tablets, mobile phones, and other devices, added to some devices using PC cards, USB modems, and USB sticks or dongles, or separate wireless modems can be used.[93]

New mobile phone technology and infrastructure is introduced periodically and generally involves a change in the fundamental nature of the service, non-backwards-compatible transmission technology, higher peak data rates, new frequency bands, wider channel frequency bandwidth in Hertz becomes available. These transitions are referred to as generations. The first mobile data services became available during the second generation (2G).

| Speeds in kbit/s | down and up | |

|---|---|---|

| · GSM CSD | 9.6 kbit/s | |

| · CDPD | up to 19.2 kbit/s | |

| · GSM GPRS (2.5G) | 56 to 115 kbit/s | |

| · GSM EDGE (2.75G) | up to 237 kbit/s | |

| Speeds in Mbit/s | down | up |

|---|---|---|

| · UMTS W-CDMA | 0.4 Mbit/s | |

| · UMTS HSPA | 14.4 | 5.8 |

| · UMTS TDD | 16 Mbit/s | |

| · CDMA2000 1xRTT | 0.3 | 0.15 |

| · CDMA2000 EV-DO | 2.5–4.9 | 0.15–1.8 |

| · GSM EDGE-Evolution | 1.6 | 0.5 |

| Speeds in Mbit/s | down | up | |

|---|---|---|---|

| · | HSPA+ | 21–672 | 5.8–168 |

| · | Mobile WiMAX (802.16) | 37–365 | 17–376 |

| · | LTE | 100–300 | 50–75 |

| · | LTE-Advanced: | ||

| · moving at higher speeds | 100 Mbit/s | ||

| · not moving or moving at lower speeds | up to 1000 Mbit/s | ||

| · | MBWA (802.20) | 80 Mbit/s | |

The download (to the user) and upload (to the Internet) data rates given above are peak or maximum rates and end users will typically experience lower data rates.

WiMAX was originally developed to deliver fixed wireless service with wireless mobility added in 2005. CDPD, CDMA2000 EV-DO, and MBWA are no longer being actively developed.

In 2011, 90% of the world's population lived in areas with 2G coverage, while 45% lived in areas with 2G and 3G coverage.[94]

5G was designed to be faster and have lower latency than its predecessor, 4G. It can be used for mobile broadband in smartphones or separate modems that emit WiFi or can be connected through USB to a computer, or for fixed wireless.

Fixed wireless

[edit]Fixed wireless internet connections that do not use a satellite nor are designed to support moving equipment such as smartphones due to the use of, for example, customer premises equipment such as antennas that can't be moved over a significant geographical area without losing the signal from the ISP, unlike smartphones. Microwave wireless broadband or 5G may be used for fixed wireless.

WiMAX

[edit]Worldwide Interoperability for Microwave Access (WiMAX) is a set of interoperable implementations of the IEEE 802.16 family of wireless-network standards certified by the WiMAX Forum. It enables "the delivery of last mile wireless broadband access as an alternative to cable and DSL".[95] The original IEEE 802.16 standard, now called "Fixed WiMAX", was published in 2001 and provided 30 to 40 megabit-per-second data rates.[96] Mobility support was added in 2005. A 2011 update provides data rates up to 1 Gbit/s for fixed stations. WiMax offers a metropolitan area network with a signal radius of about 50 km (30 miles), far surpassing the 30-metre (100-foot) wireless range of a conventional Wi-Fi LAN. WiMAX signals also penetrate building walls much more effectively than Wi-Fi. WiMAX is most often used as a fixed wireless standard.

Wireless ISP

[edit]

Wireless Internet service providers (WISPs) operate independently of mobile phone operators. WISPs typically employ low-cost IEEE 802.11 Wi-Fi radio systems to link up remote locations over great distances (Long-range Wi-Fi), but may use other higher-power radio communications systems as well, such as microwave and WiMAX.

Traditional 802.11a/b/g/n/ac is an unlicensed omnidirectional service designed to span between 100 and 150 m (300 to 500 ft). By focusing the radio signal using a directional antenna (where allowed by regulations), 802.11 can operate reliably over a distance of many km(miles), although the technology's line-of-sight requirements hamper connectivity in areas with hilly or heavily foliated terrain. In addition, compared to hard-wired connectivity, there are security risks (unless robust security protocols are enabled); data rates are usually slower (2 to 50 times slower); and the network can be less stable, due to interference from other wireless devices and networks, weather and line-of-sight problems.[97]

With the increasing popularity of unrelated consumer devices operating on the same 2.4 GHz band, many providers have migrated to the 5GHz ISM band. If the service provider holds the necessary spectrum license, it could also reconfigure various brands of off the shelf Wi-Fi hardware to operate on its own band instead of the crowded unlicensed ones. Using higher frequencies carries various advantages:

- usually regulatory bodies allow for more power and using (better-) directional antennae,

- there exists much more bandwidth to share, allowing both better throughput and improved coexistence,

- there are fewer consumer devices that operate over 5 GHz than over 2.4 GHz, hence fewer interferers are present,

- the shorter wavelengths don't propagate as well through walls and other structures, so much less interference leaks outside of the homes of consumers.

Proprietary technologies like Motorola Canopy & Expedience can be used by a WISP to offer wireless access to rural and other markets that are hard to reach using Wi-Fi or WiMAX. There are a number of companies that provide this service.[98]

Local Multipoint Distribution Service

[edit]Local Multipoint Distribution Service (LMDS) is a broadband wireless access technology that uses microwave signals operating between 26 GHz and 29 GHz.[99] Originally designed for digital television transmission (DTV), it is conceived as a fixed wireless, point-to-multipoint technology for utilization in the last mile. Data rates range from 64 kbit/s to 155 Mbit/s.[100] Distance is typically limited to about 1.5 miles (2.4 km), but links of up to 5 miles (8 km) from the base station are possible in some circumstances.[101]

LMDS has been surpassed in both technological and commercial potential by the LTE and WiMAX standards.

Hybrid Access Networks

[edit]In some regions, notably in rural areas, the length of the copper lines makes it difficult for network operators to provide high-bandwidth services. One alternative is to combine a fixed-access network, typically XDSL, with a wireless network, typically LTE. The Broadband Forum has standardized an architecture for such Hybrid Access Networks.

Non-commercial alternatives for using Internet services

[edit]Grassroots wireless networking movements

[edit]Deploying multiple adjacent Wi-Fi access points is sometimes used to create city-wide wireless networks.[102] It is usually ordered by the local municipality from commercial WISPs.

Grassroots efforts have also led to wireless community networks widely deployed in numerous countries, both developing and developed ones. Rural wireless-ISP installations are typically not commercial in nature and are instead a patchwork of systems built up by hobbyists mounting antennas on radio masts and towers, agricultural storage silos, very tall trees, or whatever other tall objects are available.

Where radio spectrum regulation is not community-friendly, the channels are crowded or when equipment can not be afforded by local residents, free-space optical communication can also be deployed in a similar manner for point to point transmission in air (rather than in fiber optic cable).

Packet radio

[edit]Packet radio connects computers or whole networks operated by radio amateurs with the option to access the Internet. Note that as per the regulatory rules outlined in the HAM license, Internet access and email should be strictly related to the activities of hardware amateurs.

Sneakernet

[edit]The term, a tongue-in-cheek play on net(work) as in Internet or Ethernet, refers to the wearing of sneakers as the transport mechanism for the data.

For those who do not have access to or can not afford broadband at home, downloading large files and disseminating information is done by transmission through workplace or library networks, taken home and shared with neighbors by sneakernet. The Cuban El Paquete Semanal is an organized example of this.

There are various decentralized, delay tolerant peer to peer applications which aim to fully automate this using any available interface, including both wireless (Bluetooth, Wi-Fi mesh, P2P or hotspots) and physically connected ones (USB storage, Ethernet, etc.).

Sneakernets may also be used in tandem with computer network data transfer to increase data security or overall throughput for big data use cases. Innovation continues in the area to this day; for example, AWS has recently announced Snowball, and bulk data processing is also done in a similar fashion by many research institutes and government agencies.

Pricing and spending

[edit]

Internet access is limited by the relation between pricing and available resources to spend. Regarding the latter, it is estimated that 40% of the world's population has less than US$20 per year available to spend on information and communications technology (ICT).[104] In Mexico, the poorest 30% of the society spend an estimated US$35 per year (US$3 per month) and in Brazil, the poorest 22% of the population merely has US$9 per year to spend on ICT (US$0.75 per month). From Latin America, it is known that the borderline between ICT as a necessity good and ICT as a luxury good is roughly around the "magical number" of US$10 per person per month, or US$120 per year.[104] This is the amount of ICT spending people esteem to be a basic necessity. Current Internet access prices exceed the available resources by large in many countries.

Dial-up users pay the costs for making local or long-distance phone calls, usually pay a monthly subscription fee, and may be subject to additional per minute or traffic based charges, and connect time limits by their ISP. Though less common today than in the past, some dial-up access is offered for "free" in return for watching banner ads as part of the dial-up service. NetZero, BlueLight, Juno, Freenet (NZ), and Free-nets are examples of services providing free access. Some Wireless community networks continue the tradition of providing free Internet access.

Fixed broadband Internet access is often sold under an "unlimited" or flat rate pricing model, with price determined by the maximum data rate chosen by the customer, rather than a per minute or traffic based charge. Per minute and traffic based charges and traffic caps are common for mobile broadband Internet access.

Internet services like Facebook, Wikipedia and Google have built special programs to partner with mobile network operators (MNO) to introduce zero-rating the cost for their data volumes as a means to provide their service more broadly into developing markets.[105]

With increased consumer demand for streaming content such as video on demand and peer-to-peer file sharing, demand for bandwidth has increased rapidly and for some ISPs the flat rate pricing model may become unsustainable. However, with fixed costs estimated to represent 80–90% of the cost of providing broadband service, the marginal cost to carry additional traffic is low. Most ISPs do not disclose their costs, but the cost to transmit a gigabyte of data in 2011 was estimated to be about $0.03.[106]

Some ISPs estimate that a small number of their users consume a disproportionate portion of the total bandwidth. In response some ISPs are considering, are experimenting with, or have implemented combinations of traffic based pricing, time of day or "peak" and "off peak" pricing, and bandwidth or traffic caps. Others claim that because the marginal cost of extra bandwidth is very small with 80 to 90 percent of the costs fixed regardless of usage level, that such steps are unnecessary or motivated by concerns other than the cost of delivering bandwidth to the end user.[107][108][109]

In Canada, Rogers Hi-Speed Internet and Bell Canada have imposed bandwidth caps.[107] In 2008 Time Warner began experimenting with usage-based pricing in Beaumont, Texas.[110] In 2009 an effort by Time Warner to expand usage-based pricing into the Rochester, New York area met with public resistance, however, and was abandoned.[111] On August 1, 2012, in Nashville, Tennessee and on October 1, 2012, in Tucson, Arizona Comcast began tests that impose data caps on area residents. In Nashville exceeding the 300 Gbyte cap mandates a temporary purchase of 50 Gbytes of additional data.[112]

Digital divide

[edit]

as a percentage of a country's population

as a percentage of a country's population

Despite its tremendous growth, Internet access is not distributed equally within or between countries.[117][118] The digital divide refers to "the gap between people with effective access to information and communications technology (ICT), and those with very limited or no access". The gap between people with Internet access and those without is one of many aspects of the digital divide.[119] Whether someone has access to the Internet can depend greatly on financial status, geographical location as well as government policies. "Low-income, rural, and minority populations have received special scrutiny as the technological 'have-nots'."[120]

Government policies play a tremendous role in bringing Internet access to or limiting access for underserved groups, regions, and countries. For example, in Pakistan, which is pursuing an aggressive IT policy aimed at boosting its drive for economic modernization, the number of Internet users grew from 133,900 (0.1% of the population) in 2000 to 31 million (17.6% of the population) in 2011.[121] In North Korea there is relatively little access to the Internet due to the governments' fear of political instability that might accompany the benefits of access to the global Internet.[122] The U.S. trade embargo is a barrier limiting Internet access in Cuba.[123]

Access to computers is a dominant factor in determining the level of Internet access. In 2011, in developing countries, 25% of households had a computer and 20% had Internet access, while in developed countries the figures were 74% of households had a computer and 71% had Internet access.[94] The majority of people in developing countries do not have Internet access.[124] About 4 billion people do not have Internet access.[125] When buying computers was legalized in Cuba in 2007, the private ownership of computers soared (there were 630,000 computers available on the island in 2008, a 23% increase over 2007).[126][127]

Internet access has changed the way in which many people think and has become an integral part of people's economic, political, and social lives. The United Nations has recognized that providing Internet access to more people in the world will allow them to take advantage of the "political, social, economic, educational, and career opportunities" available over the Internet.[118] Several of the 67 principles adopted at the World Summit on the Information Society convened by the United Nations in Geneva in 2003, directly address the digital divide.[128] To promote economic development and a reduction of the digital divide, national broadband plans have been and are being developed to increase the availability of affordable high-speed Internet access throughout the world. The Global Gateway, the EU's initiative to assist infrastructure development throughout the world, plans to raise €300 billion for connectivity projects, including those in the digital sector, between 2021 and 2027.[129][130]

Growth in number of users

[edit]| 2005 | 2010 | 2017 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World population (billions)[132] | 6.5 | 6.9 | 7.4 | 8.0 |

| Worldwide | 16% | 30% | 48% | 67% |

| In developing world | 8% | 21% | 41.3% | 60% |

| In developed world | 51% | 67% | 81% | 93% |

| Region | 2005 | 2010 | 2017 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 2% | 10% | 21.8% | 37% |

| Americas | 36% | 49% | 65.9% | 87% |

| Arab States | 8% | 26% | 43.7% | 69% |

| Asia and Pacific | 9% | 23% | 43.9% | 66% |

| Commonwealth of Independent States |

10% | 34% | 67.7% | 89% |

| Europe | 46% | 67% | 79.6% | 91% |

Access to the Internet grew from an estimated 10 million people in 1993, to almost 40 million in 1995, to 670 million in 2002, and to 2.7 billion in 2013.[133] With market saturation, growth in the number of Internet users is slowing in industrialized countries, but continues in Asia,[134] Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and the Middle East. Across Africa, an estimated 900 million people are still not connected to the internet; for those who are, connectivity fees remain generally expensive, and bandwidth is severely constrained in many locations.[135][136] The number of mobile customers in Africa, however, is expanding faster than everywhere else. Mobile financial services also allow for immediate payment of products and services.[137][138][139]

There were roughly 0.6 billion fixed broadband subscribers and almost 1.2 billion mobile broadband subscribers in 2011.[140] In developed countries people frequently use both fixed and mobile broadband networks. In developing countries mobile broadband is often the only access method available.[94]

Bandwidth divide

[edit]Traditionally the divide has been measured in terms of the existing numbers of subscriptions and digital devices ("have and have-not of subscriptions"). Recent studies have measured the digital divide not in terms of technological devices, but in terms of the existing bandwidth per individual (in kbit/s per capita).[116][141] As shown in the Figure on the side, the digital divide in kbit/s is not monotonically decreasing, but re-opens up with each new innovation. For example, "the massive diffusion of narrow-band Internet and mobile phones during the late 1990s" increased digital inequality, as well as "the initial introduction of broadband DSL and cable modems during 2003–2004 increased levels of inequality".[141] This is because a new kind of connectivity is never introduced instantaneously and uniformly to society as a whole at once, but diffuses slowly through social networks. As shown by the Figure, during the mid-2000s, communication capacity was more unequally distributed than during the late 1980s, when only fixed-line phones existed. The most recent increase in digital equality stems from the massive diffusion of the latest digital innovations (i.e. fixed and mobile broadband infrastructures, e.g. 3G and fiber optics FTTH).[142] As shown in the Figure, Internet access in terms of bandwidth is more unequally distributed in 2014 as it was in the mid-1990s.

For example, only 0.4% of the African population has a fixed-broadband subscription. The majority of internet users use it through mobile broadband.[135][136][143][144]

Rural access

[edit]One of the great challenges for Internet access in general and for broadband access in particular is to provide service to potential customers in areas of low population density, such as to farmers, ranchers, and small towns. In cities where the population density is high, it is easier for a service provider to recover equipment costs, but each rural customer may require expensive equipment to get connected. While 66% of Americans had an Internet connection in 2010, that figure was only 50% in rural areas, according to the Pew Internet & American Life Project.[145] Virgin Media advertised over 100 towns across the United Kingdom "from Cwmbran to Clydebank" that have access to their 100 Mbit/s service.[33]

Wireless Internet service providers (WISPs) are rapidly becoming a popular broadband option for rural areas.[146] The technology's line-of-sight requirements may hamper connectivity in some areas with hilly and heavily foliated terrain. However, the Tegola project, a successful pilot in remote Scotland, demonstrates that wireless can be a viable option.[147]

The Canadian Broadband for Rural Nova Scotia initiative public private partnership is the first program in North America to guarantee access to "100% of civic addresses" in a region. It is based on Motorola Canopy technology. As of November 2011, under 1000 households have reported access problems. Deployment of a new cell network by one Canopy provider (Eastlink) was expected to provide the alternative of 3G/4G service, possibly at a special unmetered rate, for areas harder to serve by Canopy.[148]

In New Zealand, a fund has been formed by the government to improve rural broadband,[149] and mobile phone coverage. Current proposals include: (a) extending fiber coverage and upgrading copper to support VDSL, (b) focusing on improving the coverage of cellphone technology, or (c) regional wireless.[150]

Several countries have started Hybrid Access Networks to provide faster Internet services in rural areas by enabling network operators to efficiently combine their XDSL and LTE networks.

Access as a civil or human right

[edit]The actions, statements, opinions, and recommendations outlined below have led to the suggestion that Internet access itself is or should become a civil or perhaps a human right.[151][152]

Several countries have adopted laws requiring the state to work to ensure that Internet access is broadly available or preventing the state from unreasonably restricting an individual's access to information and the Internet:

- Costa Rica: A 30 July 2010 ruling by the Supreme Court of Costa Rica stated: "Without fear of equivocation, it can be said that these technologies [information technology and communication] have impacted the way humans communicate, facilitating the connection between people and institutions worldwide and eliminating barriers of space and time. At this time, access to these technologies becomes a basic tool to facilitate the exercise of fundamental rights and democratic participation (e-democracy) and citizen control, education, freedom of thought and expression, access to information and public services online, the right to communicate with the government electronically and administrative transparency, among others. This includes the fundamental right of access to these technologies, in particular, the right of access to the Internet or World Wide Web."[153]

- Estonia: In 2000, the parliament launched a massive program to expand access to the countryside. The Internet, the government argues, is essential for life in the twenty-first century.[154]

- Finland: By July 2010, every person in Finland was to have access to a one-megabit per second broadband connection, according to the Ministry of Transport and Communications. And by 2015, access to a 100 Mbit/s connection.[155]

- France: In June 2009, the Constitutional Council, France's highest court, declared access to the Internet to be a basic human right in a strongly-worded decision that struck down portions of the HADOPI law, a law that would have tracked abusers and without judicial review automatically cut off network access to those who continued to download illicit material after two warnings[156]

- Greece: Article 5A of the Constitution of Greece states that all persons has a right to participate in the Information Society and that the state has an obligation to facilitate the production, exchange, diffusion, and access to electronically transmitted information.[157]

- Spain: Starting in 2011, Telefónica, the former state monopoly that holds the country's "universal service" contract, has to guarantee to offer "reasonably" priced broadband of at least one megabyte per second throughout Spain.[158]

In December 2003, the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) was convened under the auspice of the United Nations. After lengthy negotiations between governments, businesses and civil society representatives the WSIS Declaration of Principles was adopted reaffirming the importance of the Information Society to maintaining and strengthening human rights:[128] [159]

- 1. We, the representatives of the peoples of the world, assembled in Geneva from 10–12 December 2003 for the first phase of the World Summit on the Information Society, declare our common desire and commitment to build a people-centered, inclusive and development-oriented Information Society, where everyone can create, access, utilize and share information and knowledge, enabling individuals, communities and peoples to achieve their full potential in promoting their sustainable development and improving their quality of life, premised on the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and respecting fully and upholding the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- 3. We reaffirm the universality, indivisibility, interdependence and interrelation of all human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the right to development, as enshrined in the Vienna Declaration. We also reaffirm that democracy, sustainable development, and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms as well as good governance at all levels are interdependent and mutually reinforcing. We further resolve to strengthen the rule of law in international as in national affairs.

The WSIS Declaration of Principles makes specific reference to the importance of the right to freedom of expression in the "Information Society" in stating:

- 4. We reaffirm, as an essential foundation of the Information Society, and as outlined in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; that this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers. Communication is a fundamental social process, a basic human need and the foundation of all social organization. It is central to the Information Society. Everyone, everywhere should have the opportunity to participate and no one should be excluded from the benefits of the Information Society offers."[159]

A poll of 27,973 adults in 26 countries, including 14,306 Internet users,[160] conducted for the BBC World Service between 30 November 2009 and 7 February 2010 found that almost four in five Internet users and non-users around the world felt that access to the Internet was a fundamental right.[161] 50% strongly agreed, 29% somewhat agreed, 9% somewhat disagreed, 6% strongly disagreed, and 6% gave no opinion.[162]

The 88 recommendations made by the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression in a May 2011 report to the Human Rights Council of the United Nations General Assembly include several that bear on the question of the right to Internet access:[163]

- 67. Unlike any other medium, the Internet enables individuals to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds instantaneously and inexpensively across national borders. By vastly expanding the capacity of individuals to enjoy their right to freedom of opinion and expression, which is an "enabler" of other human rights, the Internet boosts economic, social and political development, and contributes to the progress of humankind as a whole. In this regard, the Special Rapporteur encourages other Special Procedures mandate holders to engage on the issue of the Internet with respect to their particular mandates.

- 78. While blocking and filtering measures deny users access to specific content on the Internet, States have also taken measures to cut off access to the Internet entirely. The Special Rapporteur considers cutting off users from Internet access, regardless of the justification provided, including on the grounds of violating intellectual property rights law, to be disproportionate and thus a violation of article 19, paragraph 3, of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

- 79. The Special Rapporteur calls upon all States to ensure that Internet access is maintained at all times, including during times of political unrest.

- 85. Given that the Internet has become an indispensable tool for realizing a range of human rights, combating inequality, and accelerating development and human progress, ensuring universal access to the Internet should be a priority for all States. Each State should thus develop a concrete and effective policy, in consultation with individuals from all sections of society, including the private sector and relevant Government ministries, to make the Internet widely available, accessible and affordable to all segments of population.

Network neutrality

[edit]| Part of a series about |

| Net neutrality |

|---|

| Topics and issues |

| By country or region |

Network neutrality (also net neutrality, Internet neutrality, or net equality) is the principle that Internet service providers and governments should treat all data on the Internet equally, not discriminating or charging differentially by user, content, site, platform, application, type of attached equipment, or mode of communication.[164][165][166][167] Advocates of net neutrality have raised concerns about the ability of broadband providers to use their last mile infrastructure to block Internet applications and content (e.g. websites, services, and protocols), and even to block out competitors.[168] Opponents claim net neutrality regulations would deter investment into improving broadband infrastructure and try to fix something that isn't broken.[169][170] In April 2017, a recent attempt to compromise net neutrality in the United States is being considered by the newly appointed FCC chairman, Ajit Varadaraj Pai.[171] The vote on whether or not to abolish net neutrality was passed on December 14, 2017, and ended in a 3–2 split in favor of abolishing net neutrality.

Natural disasters and access

[edit]Natural disasters disrupt internet access in profound ways. This is important—not only for telecommunication companies who own the networks and the businesses who use them, but for emergency crew and displaced citizens as well. The situation is worsened when hospitals or other buildings necessary for disaster response lose their connection. Knowledge gained from studying past internet disruptions by natural disasters could be put to use in planning or recovery. Additionally, because of both natural and man-made disasters, studies in network resiliency are now being conducted to prevent large-scale outages.[172]

One way natural disasters impact internet connection is by damaging end sub-networks (subnets), making them unreachable. A study on local networks after Hurricane Katrina found that 26% of subnets within the storm coverage were unreachable.[173] At Hurricane Katrina's peak intensity, almost 35% of networks in Mississippi were without power, while around 14% of Louisiana's networks were disrupted.[174] Of those unreachable subnets, 73% were disrupted for four weeks or longer and 57% were at "network edges were important emergency organizations such as hospitals and government agencies are mostly located".[173] Extensive infrastructure damage and inaccessible areas were two explanations for the long delay in returning service.[173] The company Cisco has revealed a Network Emergency Response Vehicle (NERV), a truck that makes portable communications possible for emergency responders despite traditional networks being disrupted.[175]

A second way natural disasters destroy internet connectivity is by severing submarine cables—fiber-optic cables placed on the ocean floor that provide international internet connection. A sequence of undersea earthquakes cut six out of seven international cables connected to Taiwan and caused a tsunami that wiped out one of its cable and landing stations.[176][177] The impact slowed or disabled internet connection for five days within the Asia-Pacific region as well as between the region and the United States and Europe.[178]

With the rise in popularity of cloud computing, concern has grown over access to cloud-hosted data in the event of a natural disaster. Amazon Web Services (AWS) has been in the news for major network outages in April 2011 and June 2012.[179][180] AWS, like other major cloud hosting companies, prepares for typical outages and large-scale natural disasters with backup power as well as backup data centers in other locations. AWS divides the globe into five regions and then splits each region into availability zones. A data center in one availability zone should be backed up by a data center in a different availability zone. Theoretically, a natural disaster would not affect more than one availability zone.[181] This theory plays out as long as human error is not added to the mix. The June 2012 major storm only disabled the primary data center, but human error disabled the secondary and tertiary backups, affecting companies such as Netflix, Pinterest, Reddit, and Instagram.[182][183]

See also

[edit]- Back-channel, a low bandwidth, or less-than-optimal, transmission channel in the opposite direction to the main channel

- Broadband mapping in the United States

- Comparison of wireless data standards

- Connectivity in a social and cultural sense

- Fiber-optic communication

- History of the Internet

- IP over DVB, Internet access using MPEG data streams over a digital television network

- List of countries by number of broadband Internet subscriptions

- National broadband plan

- Public switched telephone network (PSTN)

- Residential gateway

- White spaces (radio), a group of technology companies working to deliver broadband Internet access via unused analog television frequencies

References

[edit]- ^ "Internet Connection Types Explained". CNET. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ Robinson, Zachary A. (2015-06-26). The world transformed : 1945 to the present. Oxford University Press. p. 431. ISBN 9780199371020. OCLC 907585907.

- ^ Robinson, Zachary A. (2015-06-26). The world transformed : 1945 to the present. Oxford University Press. pp. 431–432. ISBN 9780199371020. OCLC 907585907.

- ^ "Akamai Releases Second Quarter 2014 'State of the Internet' Report". Akamai. 30 September 2014. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ Segal, Ben (1995). A short history of Internet protocols at CERN. Geneva: CERN (published April 1995). doi:10.17181/CERN_TCP_IP_history.

- ^ Réseaux IP Européens (RIPE)

- ^ "Internet History in Asia". 16th APAN Meetings/Advanced Network Conference in Busan. Archived from the original on 1 February 2006. Retrieved 25 December 2005.

- ^ "Retiring the NSFNET Backbone Service: Chronicling the End of an Era" Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine, Susan R. Harris and Elise Gerich, ConneXions, Vol. 10, No. 4, April 1996

- ^ a b Jindal, R. P. (2009). "From millibits to terabits per second and beyond - over 60 years of innovation". 2009 2nd International Workshop on Electron Devices and Semiconductor Technology. pp. 1–6. doi:10.1109/EDST.2009.5166093. ISBN 978-1-4244-3831-0. S2CID 25112828. Archived from the original on 2019-08-23. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- ^ US2802760A, Lincoln, Derick & Frosch, Carl J., "Oxidation of semiconductive surfaces for controlled diffusion", issued 1957-08-13

- ^ Frosch, C. J.; Derick, L (1957). "Surface Protection and Selective Masking during Diffusion in Silicon". Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 104 (9): 547. doi:10.1149/1.2428650.

- ^ KAHNG, D. (1961). "Silicon-Silicon Dioxide Surface Device". Technical Memorandum of Bell Laboratories: 583–596. doi:10.1142/9789814503464_0076. ISBN 978-981-02-0209-5.

{{cite journal}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. p. 321. ISBN 978-3-540-34258-8.

- ^ Ligenza, J.R.; Spitzer, W.G. (1960). "The mechanisms for silicon oxidation in steam and oxygen". Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids. 14: 131–136. Bibcode:1960JPCS...14..131L. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(60)90219-5.

- ^ Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 120. ISBN 9783540342588.

- ^ "Triumph of the MOS Transistor". YouTube. Computer History Museum. 6 August 2010. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Raymer, Michael G. (2009). The Silicon Web: Physics for the Internet Age. CRC Press. p. 365. ISBN 9781439803127. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- ^ "What is Broadband?". The National Broadband Plan. US Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ^ "Inquiry Concerning the Deployment of Advanced Telecommunications Capability to All Americans in a Reasonable and Timely Fashion, and Possible Steps to Accelerate Such Deployment Pursuant to Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, as Amended by the Broadband Data Improvement Act" (PDF). GN Docket No. 10-159, FCC-10-148A1. Federal Communications Commission. August 6, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ Geerts, Yves; Steyaert, Michiel; Sansen, Willy (2013) [1st pub. 2004]. "Chapter 8: Single-Loop Multi-Bit Sigma-Delta Modulators". In Rodríguez-Vázquez, Angel; Medeiro, Fernando; Janssens, Edmond (eds.). CMOS Telecom Data Converters. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-4757-3724-0. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ a b Green, M. M. (November 2010). "An overview on wireline communication systems for high-speed broadband communication". Proceedings of Papers 5th European Conference on Circuits and Systems for Communications (ECCSC'10): 1–8. Archived from the original on 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ a b c d "How Broadband Works" Archived 2011-09-13 at the Wayback Machine, Chris Woodford, Explain that Stuff, 20 August 2008. Retrieved 19 January.

- ^ Jeffrey A. Hart; Robert R. Reed; François Bar (November 1992). "The building of the Internet: Implications for the future of broadband networks". Telecommunications Policy. 16 (8): 666–689. doi:10.1016/0308-5961(92)90061-S. S2CID 155062650.

- ^ The 34 OECD countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. OECD members Archived 2011-04-08 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 1 May 2012

- ^ The Future of the Internet Economy: A Statistical Profile Archived 2012-06-16 at the Wayback Machine, Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), June 2011

- ^ Willdig, Karl; Patrik Chen (August 1994). "What You Need to Know about Modems". Archived from the original on 2007-01-04. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- ^ Mitronov, Pavel (2001-06-29). "Modem compression: V.44 against V.42bis". Pricenfees.com. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- ^ "Birth of Broadband". ITU. September 2003. Archived from the original on July 1, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "Recommendation I.113, Vocabulary of Terms for Broadband aspects of ISDN". ITU-T. June 1997 [originally 1988]. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ "2006 OECD Broadband Statistics to December 2006". OECD. Archived from the original on 2009-05-07. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ "FCC Finds U.S. Broadband Deployment Not Keeping Pace" (PDF). FCC. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ^ Patel, Nilay (March 19, 2008). "FCC redefines "broadband" to mean 768 kbit/s, "fast" to mean "kinda slow"". Engadget. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ a b "Virgin Media's ultrafast 100Mb broadband now available to over four million UK homes". News release. Virgin Media. June 10, 2011. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ Tom Phillips (August 25, 2010). "'Misleading' BT broadband ad banned". UK Metro. Archived from the original on September 6, 2011. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ^ Ben Munson (June 29, 2016). "Akamai: Global average internet speeds have doubled since last Olympics". FierceOnlineVideo. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ "Georgian woman cuts off web access to whole of Armenia". The Guardian. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ Cowie, James. "Egypt Leaves the Internet". Renesys. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ "Egypt severs internet connection amid growing unrest". BBC News. 28 January 2011. Archived from the original on 23 January 2012.

- ^ "Router glitch cuts Net access". CNET News.com. 1997-04-25. Archived from the original on 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ "IEEE GET Program™". Archived from the original on 2017-01-24. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- ^ "Wi-Fi (wireless networking technology)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2010-06-27. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ^ Dean, Tamara (2010). Network+ Guide to Networks, 5th Ed.

- ^ "Bonding: 112K, 168K, and beyond " Archived 2007-03-10 at the Wayback Machine, 56K.com

- ^ "Diamond 56k Shotgun Modem" Archived 2012-03-31 at the Wayback Machine, maximumpc.com

- ^ William Stallings (1999). ISDN and Broadband ISDN with Frame Relay and ATM (4th ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 542. ISBN 978-0139737442. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24.

- ^ "Selecting a WAN Technology (1.2) > WAN Concepts | Cisco Press".

- ^ "Network World". 23–30 December 1996.

- ^ a b Telecommunications and Data Communications Handbook Archived 2013-03-08 at the Wayback Machine, Ray Horak, 2nd edition, Wiley-Interscience, 2008, 791 p., ISBN 0-470-39607-5

- ^ a b "Fiber optics among Carrier Ethernet's multiple access technologies". July 2009.

- ^ a b Cuffie, D.; Biesecker, K.; Kain, C.; Charleston, G.; Ma, J. (1999). "Emerging high-speed access technologies". IT Professional. 1 (2): 20–28. doi:10.1109/6294.774937.

- ^ Lehpamer, Harvey (2002). Transmission Systems Design Handbook for Wireless Networks. Artech House. ISBN 978-1-58053-243-3.

- ^ Beasley, Jeffrey S.; Nilkaew, Piyasat (5 November 2012). A Practical Guide to Advanced Networking. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-13-335400-3.

- ^ Held, Gilbert; Ravi Jagannathan, S. (11 June 2004). Practical Network Design Techniques: A Complete Guide for WANs and LANs. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-203-50745-2.

- ^ Dean, Tamara (2009). Network+ Guide to Networks (5th ed.). Course Technology, Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4239-0245-4. Archived from the original on 2013-04-20. pp 312–315.

- ^ Mukherjee, Biswanath; Tomkos, Ioannis; Tornatore, Massimo; Winzer, Peter; Zhao, Yongli (15 October 2020). Springer Handbook of Optical Networks. Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-16250-4.

- ^ "IEEE 802.3 Ethernet Working Group" Archived 2014-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, web page, IEEE 802 LAN/MAN Standards Committee, accessed 8 May 2012

- ^ a b Dean, Tamara (2009). Network+ Guide to Networks (5th ed.). Course Technology, Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4239-0245-4. Archived from the original on 2013-04-20. p 322.

- ^ Dean, Tamara (2009). Network+ Guide to Networks (5th ed.). Course Technology, Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4239-0245-4. Archived from the original on 2013-04-20. p 323.

- ^ "ADSL Theory" Archived 2010-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, Australian broadband news and information, Whirlpool, accessed 3 May 2012

- ^ "SDSL" Archived 2012-04-18 at the Wayback Machine, Internetworking Technology Handbook, Cisco DocWiki, 17 December 2009, accessed 3 May 2012

- ^ "KPN starts VDSL trials". KPN. Archived from the original on 2008-05-04.

- ^ "VDSL Speed". HowStuffWorks. 2001-05-21. Archived from the original on 2010-03-12.

- ^ "Industrial VDSL Ethernet Extender Over Coaxial Cable, ED3331". EtherWAN. Archived from the original on 2011-07-10.

- ^ "New ITU Standard Delivers 10x ADSL Speeds: Vendors applaud landmark agreement on VDSL2". News release. International Telecommunication Union. 27 May 2005. Archived from the original on 3 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ Sturgeon, Jamie (October 18, 2010). "A smarter route to high-speed Net". FP Entrepreneur. National Post. Archived from the original on October 23, 2010. Retrieved January 7, 2011.

- ^ "FTTH Council – Definition of Terms" (PDF). FTTH Council. January 9, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Oppenheimer, Priscilla (2004). Top-down Network Design. Cisco Press. ISBN 978-1-58705-152-4.

- ^ "Computerworld". 20 January 2003.

- ^ Toy, Mehmet (2 February 2015). Cable Networks, Services, and Management. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-83759-7.

- ^ "ITS Technology Claims First Live UK Biz Customer Trial of 50Gbps PON". 15 May 2025.

- ^ "FTTx Primer" Archived 2008-10-11 at the Wayback Machine, Fiopt Communication Services (Calgary), July 2008

- ^ Fiber Optic Installer's Field Manual. McGraw Hill Professional. 13 July 2000. ISBN 978-0-07-137842-0.

- ^ "Big gig: NBN to be 10 times faster" Archived 2012-04-29 at the Wayback Machine, Emma Rodgers, ABC News, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 12 August 2010

- ^ "Italy gets fiber back on track" Archived 2012-03-22 at the Wayback Machine, Michael Carroll, TelecomsEMEA.net, 20 September 2010

- ^ "Pirelli Broadband Solutions, the technology partner of fastweb network Ngan" Archived 2012-03-28 at the Wayback Machine, 2 August 2010

- ^ "Telecom Italia rolls out 100 Mbps FTTH services in Catania" Archived 2010-12-31 at the Wayback Machine, Sean Buckley, FierceTelecom, 3 November 2010

- ^ "SaskTel Announces 2011 Network Investment and Fiber to the Premises Program" Archived 2012-09-11 at archive.today, SaskTel, Saskatchewan Telecommunications Holding Corporation, 5 April 2011