Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Argument (linguistics)

View on Wikipedia| Grammatical features |

|---|

In linguistics, an argument is an expression that helps complete the meaning of a predicate,[1] the latter referring in this context to a main verb and its auxiliaries. In this regard, the complement is a closely related concept. Most predicates take one, two, or three arguments. A predicate and its arguments form a predicate-argument structure. The discussion of predicates and arguments is associated most with (content) verbs and noun phrases (NPs), although other syntactic categories can also be construed as predicates and as arguments. Arguments must be distinguished from adjuncts. While a predicate needs its arguments to complete its meaning, the adjuncts that appear with a predicate are optional; they are not necessary to complete the meaning of the predicate.[2] Most theories of syntax and semantics acknowledge arguments and adjuncts, although the terminology varies, and the distinction is generally believed to exist in all languages. Dependency grammars sometimes call arguments actants, following Lucien Tesnière (1959).

The area of grammar that explores the nature of predicates, their arguments, and adjuncts is called valency theory. Predicates have a valence; they determine the number and type of arguments that can or must appear in their environment. The valence of predicates is also investigated in terms of subcategorization.

Arguments and adjuncts

[edit]The basic analysis of the syntax and semantics of clauses relies heavily on the distinction between arguments and adjuncts. The clause predicate, which is often a content verb, demands certain arguments. That is, the arguments are necessary in order to complete the meaning of the verb. The adjuncts that appear, in contrast, are not necessary in this sense. The subject phrase and object phrase are the two most frequently occurring arguments of verbal predicates.[3] For instance:

- Jill likes Jack.

- Sam fried the vegetables.

- The old man helped the young man.

Each of these sentences contains two arguments (in bold), the first noun (phrase) being the subject argument, and the second the object argument. Jill, for example, is the subject argument of the predicate likes, and Jack is its object argument. Verbal predicates that demand just a subject argument (e.g. sleep, work, relax) are intransitive, verbal predicates that demand an object argument as well (e.g. like, fry, help) are transitive, and verbal predicates that demand two object arguments are ditransitive (e.g. give, lend).

When additional information is added to our three example sentences, one is dealing with adjuncts, e.g.

- Jill really likes Jack.

- Jill likes Jack most of the time.

- Jill likes Jack when the sun shines.

- Jill likes Jack because he's friendly.

The added phrases (in bold) are adjuncts; they provide additional information that is not necessary to complete the meaning of the predicate likes. One key difference between arguments and adjuncts is that the appearance of a given argument is often obligatory, whereas adjuncts appear optionally. While typical verb arguments are subject or object nouns or noun phrases as in the examples above, they can also be prepositional phrases (PPs) (or even other categories). The PPs in bold in the following sentences are arguments:

- Sam put the pen on the chair.

- Larry does not put up with that.

- Bill is getting on my case.

We know that these PPs are (or contain) arguments because when we attempt to omit them, the result is unacceptable:

- *Sam put the pen.

- *Larry does not put up.

- *Bill is getting.

Subject and object arguments are known as core arguments; core arguments can be suppressed, added, or exchanged in different ways, using voice operations like passivization, antipassivization, applicativization, incorporation, etc. Prepositional arguments, which are also called oblique arguments, however, do not tend to undergo the same processes.

Psycholinguistic (argument vs adjuncts)

[edit]Psycholinguistic theories must explain how syntactic representations are built incrementally during sentence comprehension. One view that has sprung from psycholinguistics is the argument structure hypothesis (ASH), which explains the distinct cognitive operations for argument and adjunct attachment: arguments are attached via the lexical mechanism, but adjuncts are attached using general (non-lexical) grammatical knowledge that is represented as phrase structure rules or the equivalent.

Argument status determines the cognitive mechanism in which a phrase will be attached to the developing syntactic representations of a sentence. Psycholinguistic evidence supports a formal distinction between arguments and adjuncts, for any questions about the argument status of a phrase are, in effect, questions about learned mental representations of the lexical heads.[citation needed]

Syntactic vs. semantic arguments

[edit]An important distinction acknowledges both syntactic and semantic arguments. Content verbs determine the number and type of syntactic arguments that can or must appear in their environment; they impose specific syntactic functions (e.g. subject, object, oblique, specific preposition, possessor, etc.) onto their arguments. These syntactic functions will vary as the form of the predicate varies (e.g. active verb, passive participle, gerund, nominal, etc.). In languages that have morphological case, the arguments of a predicate must appear with the correct case markings (e.g. nominative, accusative, dative, genitive, etc.) imposed on them by their predicate. The semantic arguments of the predicate, in contrast, remain consistent, e.g.

- Jack is liked by Jill.

- Jill's liking Jack

- Jack's being liked by Jill

- the liking of Jack by Jill

- Jill's like for Jack

The predicate 'like' appears in various forms in these examples, which means that the syntactic functions of the arguments associated with Jack and Jill vary. The object of the active sentence, for instance, becomes the subject of the passive sentence. Despite this variation in syntactic functions, the arguments remain semantically consistent. In each case, Jill is the experiencer (= the one doing the liking) and Jack is the one being experienced (= the one being liked). In other words, the syntactic arguments are subject to syntactic variation in terms of syntactic functions, whereas the thematic roles of the arguments of the given predicate remain consistent as the form of that predicate changes.

The syntactic arguments of a given verb can also vary across languages. For example, the verb put in English requires three syntactic arguments: subject, object, locative (e. g. He put the book into the box). These syntactic arguments correspond to the three semantic arguments agent, theme, and goal. The Japanese verb oku 'put', in contrast, has the same three semantic arguments, but the syntactic arguments differ, since Japanese does not require three syntactic arguments, so it is correct to say Kare ga hon o oita ("He put the book"). The equivalent sentence in English is ungrammatical without the required locative argument, as the examples involving put above demonstrate. For this reason, a slight paraphrase is required to render the nearest grammatical equivalent in English: He positioned the book or He deposited the book.

Distinguishing between arguments and adjuncts

[edit]Arguments vs. adjuncts

[edit]This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. (January 2013) |

A large body of literature has been devoted to distinguishing arguments from adjuncts.[4] Numerous syntactic tests have been devised for this purpose. One such test is the relative clause diagnostic. If the test constituent can appear after the combination which occurred/happened in a relative clause, it is an adjunct, not an argument, e.g.

- Bill left on Tuesday. → Bill left, which happened on Tuesday. – on Tuesday is an adjunct.

- Susan stopped due to the weather. → Susan stopped, which occurred due to the weather. – due to the weather is an adjunct.

- Fred tried to say something twice. → Fred tried to say something, which occurred twice. – twice is an adjunct.

The same diagnostic results in unacceptable relative clauses (and sentences) when the test constituent is an argument, e.g.

- Bill left home. → *Bill left, which happened home. – home is an argument.

- Susan stopped her objections. → *Susan stopped, which occurred her objections. – her objections is an argument.

- Fred tried to say something. → *Fred tried to say, which happened something. – something is an argument.

This test succeeds in identifying prepositional arguments as well:

- We are waiting for Susan. → *We are waiting, which is happening for Susan. – for Susan is an argument.

- Tom put the knife in the drawer. → *Tom put the knife, which occurred in the drawer. – in the drawer is an argument.

- We laughed at you. → *We laughed, which occurred at you. – at you is an argument.

The utility of the relative clause test is, however, limited. It incorrectly suggests, for instance, that modal adverbs (e.g. probably, certainly, maybe) and manner expressions (e.g. quickly, carefully, totally) are arguments. If a constituent passes the relative clause test, however, one can be sure that it is not an argument.

Obligatory vs. optional arguments

[edit]A further division blurs the line between arguments and adjuncts. Many arguments behave like adjuncts with respect to another diagnostic, the omission diagnostic. Adjuncts can always be omitted from the phrase, clause, or sentence in which they appear without rendering the resulting expression unacceptable. Some arguments (obligatory ones), in contrast, cannot be omitted. There are many other arguments, however, that are identified as arguments by the relative clause diagnostic but that can nevertheless be omitted, e.g.

- a. She cleaned the kitchen.

- b. She cleaned. – the kitchen is an optional argument.

- a. We are waiting for Larry.

- b. We are waiting. – for Larry is an optional argument.

- a. Susan was working on the model.

- b. Susan was working. – on the model is an optional argument.

The relative clause diagnostic would identify the constituents in bold as arguments. The omission diagnostic here, however, demonstrates that they are not obligatory arguments. They are, rather, optional. The insight, then, is that a three-way division is needed. On the one hand, one distinguishes between arguments and adjuncts, and on the other hand, one allows for a further division between obligatory and optional arguments.

Arguments and adjuncts in noun phrases

[edit]Most work on the distinction between arguments and adjuncts has been conducted at the clause level and has focused on arguments and adjuncts to verbal predicates. The distinction is crucial for the analysis of noun phrases as well, however. If it is altered somewhat, the relative clause diagnostic can also be used to distinguish arguments from adjuncts in noun phrases, e.g.

- Bill's bold reading of the poem after lunch

- *bold reading of the poem after lunch that was Bill's – Bill's is an argument.

- Bill's reading of the poem after lunch that was bold – bold is an adjunct

- *Bill's bold reading after lunch that was of the poem – of the poem is an argument

- Bill's bold reading of the poem that was after lunch – after lunch is an adjunct

- Bill's bold reading of the poem after lunch

The diagnostic identifies Bill's and of the poem as arguments, and bold and after lunch as adjuncts.

Representing arguments and adjuncts

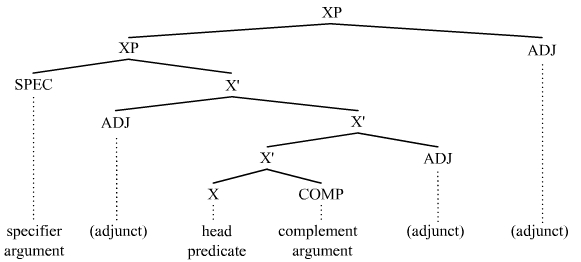

[edit]The distinction between arguments and adjuncts is often indicated in the tree structures used to represent syntactic structure. In phrase structure grammars, an adjunct is "adjoined" to a projection of its head predicate in such a manner that distinguishes it from the arguments of that predicate. The distinction is quite visible in theories that employ the X-bar schema, e.g.

The complement argument appears as a sister of the head X, and the specifier argument appears as a daughter of XP. The optional adjuncts appear in one of a number of positions adjoined to a bar-projection of X or to XP.

Theories of syntax that acknowledge n-ary branching structures and hence construe syntactic structure as being flatter than the layered structures associated with the X-bar schema must employ some other means to distinguish between arguments and adjuncts. In this regard, some dependency grammars employ an arrow convention. Arguments receive a "normal" dependency edge, whereas adjuncts receive an arrow edge.[5] In the following tree, an arrow points away from an adjunct toward the governor of that adjunct:

The arrow edges in the tree identify four constituents (= complete subtrees) as adjuncts: At one time, actually, in congress, and for fun. The normal dependency edges (= non-arrows) identify the other constituents as arguments of their heads. Thus Sam, a duck, and to his representative in congress are identified as arguments of the verbal predicate wanted to send.

Relevant theories

[edit]Argumentation theory focuses on how logical reasoning leads to end results through an internal structure built of premises, a method of reasoning and a conclusion. There are many versions of argumentation that relate to this theory that include: conversational, mathematical, scientific, interpretive, legal, and political.

Grammar theory, specifically functional theories of grammar, relate to the functions of language as the link to fully understanding linguistics by referencing grammar elements to their functions and purposes.

- Syntax theories

A variety of theories exist regarding the structure of syntax, including generative grammar, categorial grammar, and dependency grammar.

Modern theories of semantics include formal semantics, lexical semantics, and computational semantics. Formal semantics focuses on truth conditioning. Lexical Semantics delves into word meanings in relation to their context and computational semantics uses algorithms and architectures to investigate linguistic meanings.

The concept of valence is the number and type of arguments that are linked to a predicate, in particular to a verb. In valence theory verbs' arguments include also the argument expressed by the subject of the verb.

History of argument linguistics

[edit]The notion of argument structure was first conceived in the 1980s by researchers working in the government–binding framework to help address controversies about arguments.[6]

Importance

[edit]The distinction between arguments and adjuncts is crucial to most theories of syntax and grammar. Arguments behave differently from adjuncts in numerous ways. Theories of binding, coordination, discontinuities, ellipsis, etc. must acknowledge and build on the distinction. When one examines these areas of syntax, what one finds is that arguments consistently behave differently from adjuncts and that without the distinction, our ability to investigate and understand these phenomena would be seriously hindered. There is a distinction between arguments and adjuncts which is not really noticed by many in everyday language. The difference is between obligatory phrases versus phrases which embellish a sentence. For instance, if someone says "Tim punched the stuffed animal", the phrase stuffed animal would be an argument because it is the main part of the sentence. If someone says, "Tim punched the stuffed animal with glee", the phrase with glee would be an adjunct because it just enhances the sentence and the sentence can stand alone without it.[7]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Most grammars define the argument in this manner, i.e. it is an expression that helps complete the meaning of a predicate (a verb). See for instance Tesnière (1969: 128).

- ^ Concerning the completion of a predicates meaning via its arguments, see for instance Kroeger (2004:9ff.).

- ^ Geeraerts, Dirk; Cuyckens, Hubert (2007). The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-514378-2.

- ^ For instance, see the essays on valency theory in Ágel et al. (2003/6).

- ^ See Eroms (2000) and Osborne and Groß (2012) in this regard.

- ^ Levin, Beth (2013-05-28). "Argument Structure". Linguistics. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199772810-0099. ISBN 978-0-19-977281-0. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- ^ Damon Tutunjian; Julie E. Boland. "Do we need a distinction between arguments and adjuncts? Evidence from psycholinguistic studies of comprehension" (PDF). University of Michigan.

References

[edit]- Ágel, V., L. Eichinger, H.-W. Eroms, P. Hellwig, H. Heringer, and H. Lobin (eds.) 2003/6. Dependency and valency: An international handbook of contemporary research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Eroms, H.-W. 2000. Syntax der deutschen Sprache. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Kroeger, P. 2004. Analyzing syntax: A lexical-functional approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Osborne, T. and T. Groß 2012. Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets dependency grammar. Cognitive Linguistics 23, 1, 163–214.

- Tesnière, L. 1959. Éléments de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck.

- Tesnière, L. 1969. Éléments de syntaxe structurale. 2nd edition. Paris: Klincksieck.

Argument (linguistics)

View on GrokipediaCore Concepts

Definition and Role in Predication

In linguistics, an argument is a syntactic or semantic constituent required to complete the meaning of a predicate, such as a verb, by specifying the participants in the event, state, or relation denoted by that predicate.[5] Predicates, which include verbs, adjectives, or nouns functioning predicatively, express properties, actions, or relations that inherently demand certain entities to instantiate them fully, with arguments serving as those entities in roles like agent, patient, or theme.[6] For instance, in the sentence "John devours the book," the verb "devours" is the predicate, and "John" (agent) and "the book" (patient) are its arguments, without which the predicate's meaning remains incomplete.[5] The role of arguments in predication lies in saturating the predicate's valency—the fixed number and type of participants it requires to form a grammatically and semantically well-formed clause.[7] This saturation process ensures that the predicate's thematic slots, which represent conceptual roles in the described scenario, are filled, thereby yielding a complete proposition about the world.[6] Valency varies across predicates: zero-valent (or avalent) predicates like "rain" require no arguments and describe impersonal states; one-valent (monovalent or intransitive) predicates like "sleep" take a single argument, typically the subject; two-valent (divalent or transitive) predicates like "eat" require a subject and object; and three-valent (trivalent) predicates like "give" demand a subject, direct object, and indirect object.[7] These valency patterns stem from the predicate's lexical semantics, as outlined in valency theory pioneered by Lucien Tesnière, who likened a verb's need for arguments to a chemical element's bonding requirements.[7] Predicates differ from arguments in that predicates denote the core relational or attributive content, whereas arguments supply the specific referents that occupy the predicate's argument positions, often aligned with thematic roles such as agent (initiator of action) or patient (affected entity).[5] Verbs typically specify subcategorization frames in their lexical entries, which detail the syntactic categories and positions of required arguments, such as a noun phrase (NP) for the subject and another NP for the direct object in transitive verbs.[8] For example, the verb "put" has a subcategorization frame requiring an NP subject, an NP object, and a prepositional phrase (PP) indicating location, as in "She put the vase on the table."[8] This framework ensures syntactic well-formedness while linking to the semantic roles that arguments fulfill.[6] Semantic arguments emphasize the thematic contributions to meaning, while syntactic arguments focus on structural realization, though the two views often align in core cases.[6]Arguments Versus Adjuncts

In linguistics, arguments and adjuncts represent a fundamental distinction in how constituents contribute to predicate structure and sentence meaning. Arguments are the obligatory participants required to complete the valency of a predicate, such as a verb, and they typically bear core thematic roles like agent, patient, or theme, as specified in the predicate's argument structure.[9] In contrast, adjuncts are optional modifiers that provide additional circumstantial information, such as manner, time, location, or reason, without fulfilling the predicate's core requirements.[10] This opposition ensures that predicates achieve semantic completeness through arguments alone, while adjuncts enrich the description of the event without altering its basic participants.[6] A clear example illustrates this contrast in the sentence "She ran to the store quickly." Here, "she" functions as the agent argument, obligatory as the external argument of the intransitive verb "run."[9] Both "to the store" (goal adjunct) and the adverb "quickly" (manner adjunct), however, add optional information about the direction of motion and how the running occurred without being required for the verb's meaning.[10] Removing the argument would render the sentence incomplete or semantically anomalous (e.g., "*Ran to the store quickly" lacks the agent), whereas omitting the adjuncts preserves core interpretability ("She ran").[6] Semantically, arguments fill designated slots in the predicate's argument structure, encoding essential relations to the event, such as causation or affectedness, which are entailed by the predicate.[9] Adjuncts, by comparison, do not occupy these slots but instead modify the event as a whole, contributing non-entailed, descriptive content that can often be integrated across multiple predicates.[10] For instance, in "John built the house in the summer," "the house" is a patient argument entailing an affected entity, while "in the summer" is a temporal adjunct that adds context without specifying a core role.[6] Behaviorally, arguments influence predicate selection through subcategorization, where verbs impose syntactic and semantic restrictions on their complements (e.g., transitive verbs like "devour" require a direct object denoting consumable items).[6] Adjuncts lack such selectional ties and can be iterated indefinitely without violating grammaticality (e.g., "She ran to the store quickly in the morning yesterday"), highlighting their modifier status.[10] This initial distinction underscores arguments' role in defining the predicate's core event frame, distinct from adjuncts' peripheral enrichment.[9]Types of Arguments

Syntactic Arguments

In generative syntax, syntactic arguments are defined as syntactic phrases—such as noun phrases (NPs), prepositional phrases (PPs), or complementizer phrases (CPs)—that occupy designated argument positions within the hierarchical phrase structure of a sentence, typically as specifiers or complements selected by a head, particularly a verb.[11] These positions are crucial for satisfying the verb's syntactic requirements and ensuring grammatical well-formedness.[11] Common structural positions for arguments include the subject in the specifier of the Tense Phrase (Spec-TP), the direct object as the complement of the verb (V'), and indirect objects in dative constructions, often realized as PPs or NPs adjacent to the verb.[11] For instance, in English sentences like "Alex washed the car," the NP "Alex" occupies Spec-TP as the subject, while "the car" serves as the NP complement of the verb.[11] In dative constructions such as "Birch gave Brooke a book," the indirect object "Brooke" appears as an NP preceding the direct object in double object constructions or as a PP complement like "to Brooke."[12] Verbs specify their syntactic frames through subcategorization, which dictates the number and type of arguments they require; for example, transitive verbs like "hit" subcategorize for an NP complement, as in "hit the ball," while ditransitive verbs like "give" select for two NPs or an NP and a PP, as in "give a book to John."[11] This subcategorization is part of the verb's lexical entry and ensures that sentences conform to the verb's structural demands.[11] Cross-linguistically, variations arise in how these frames are realized; in ergative languages like Dyirbal or Inuit, the patient (transitive object) may occupy the Spec-TP position for case assignment, while the agent remains in the VP specifier, inverting the nominative-accusative pattern of languages like English.[13] Argument alternations demonstrate how syntactic roles can shift without altering the underlying structure in certain ways. In dative shift, a construction like "give a book to John" alternates with "give John a book," where the indirect object moves from a PP to an NP position adjacent to the verb.[12] Passivization similarly affects syntactic roles by promoting the direct object to subject position in Spec-TP, as in the shift from active "The dog attacked the cat" to passive "The cat was attacked by the dog," with the original subject demoted to a by-phrase.[11] These alternations highlight the flexibility of syntactic argument realization across constructions.[12]Semantic Arguments

In linguistics, semantic arguments refer to the entities that participate in the situation or event described by a predicate, such as a verb, with each argument fulfilling a specific interpretive role relative to that predicate. These roles, often termed theta roles or thematic roles, capture the semantic relations between the predicate and its participants, including prototypical categories like agent (the instigator of an action), theme (the entity affected or undergoing change), and goal (the endpoint or beneficiary of the action). This conceptualization originates from case grammar frameworks, where deep structural cases encode the essential semantic contributions of arguments to the proposition, independent of surface syntactic form.[14] A key constraint governing semantic arguments is the theta criterion, which stipulates that each argument must receive exactly one theta role, and each theta role assigned by the predicate must be realized by exactly one argument. Predicates thus project a fixed number of theta roles determined by their lexical semantics, ensuring a bijective mapping between arguments and roles without redundancy or omission. For instance, in the sentence "The chef sent the cake to the guests," the verb "send" assigns the agent role to "the chef" (the willful initiator), the theme role to "the cake" (the entity affected), and the goal role to "the guests" (the intended recipients). This criterion enforces the completeness and uniqueness of semantic interpretation in predication.[15] Cross-linguistically, while the syntactic expression of arguments varies—such as through word order, case marking, or agreement—core theta roles like agent, theme, experiencer (the entity perceiving or undergoing a psychological state), and goal exhibit remarkable consistency as universal components of event semantics. These roles derive from principles of Universal Grammar, providing a stable semantic-syntactic interface that structures argument participation across languages, as evidenced in typological patterns and acquisition data where children reliably distinguish initiators from affected entities early on. For example, psych verbs like "fear" universally mark the experiencer as a core participant, despite diverse realizations in languages like English (subject) versus Latin (dative). The syntactic realization of these roles, such as subject or object positions, is addressed in discussions of syntactic arguments.[16][17]Distinction Criteria

Obligatoriness and Optionality

In linguistics, obligatoriness serves as a key diagnostic for distinguishing arguments from adjuncts, with arguments being those elements required by a predicate's valency to form a complete syntactic structure. Obligatory arguments must be realized in the sentence; their omission typically results in ungrammaticality. For instance, the English ditransitive verb give requires both a theme (direct object) and a goal (indirect object) as arguments: "John gave the book to Mary" is grammatical, whereas "*John gave the book" is not, as the goal argument is missing.[18] This requirement stems from the verb's subcategorization frame, which specifies the number and type of complements needed to satisfy its valency.[19] Optional arguments, by contrast, can be omitted without rendering the sentence ungrammatical, though their absence may lead to default or contextually inferred interpretations. Such arguments are selected by the predicate but not syntactically mandated in every occurrence. For example, the English verb claim, a reporting verb, optionally takes a clausal complement: "He claimed" is grammatical on its own, implying a proposition that can be recovered from context, while "He claimed that it was true" explicitly realizes the complement for added clarity.[20] This optionality highlights how arguments contribute to semantic completeness without always enforcing syntactic presence, differing from adjuncts that add peripheral information freely.[21] Valency reduction mechanisms allow obligatory arguments to become implicit, suppressing their overt realization while preserving their semantic role. In English middle constructions, the external (agentive) argument is demoted to an implicit status, reducing the verb's syntactic valency: "The book reads easily" implies an arbitrary agent capable of reading it, but "*The book reads" without the adverb is infelicitous, as the construction requires adverbial support to license the implicit argument.[22] Similarly, zero anaphora in pro-drop languages permits the omission of phonologically null but semantically obligatory subjects, where rich verbal agreement recovers the argument's reference. Cross-linguistically, Romance languages like Italian exemplify this through null subjects in pro-drop systems, where the subject argument is obligatory for predication but optionally unrealized morphologically. In "Parla italiano" ('(He/She) speaks Italian'), the null subject pro fills the obligatory subject position, licensed by the verb's agreement morphology, without affecting grammaticality; overt pronouns like "Lui parla italiano" are used for emphasis or contrast but are not required. This contrasts with non-pro-drop languages like English, where subjects must be overt, underscoring how obligatoriness interacts with language-specific licensing conditions for arguments.[21]Structural and Behavioral Tests

Structural and behavioral tests provide syntactic diagnostics to distinguish arguments from adjuncts, complementing preliminary criteria such as obligatoriness. These tests examine how phrases interact with core syntactic operations like binding, movement, and coordination, revealing differences in structural integration. Arguments typically occupy positions within the verb phrase that allow them to participate in these operations, whereas adjuncts, being externally merged, exhibit distinct behaviors.[23] One key structural test involves c-command relations, particularly through binding asymmetries under Principle C of the Binding Theory. Arguments c-command their dependents, enabling coreference restrictions, while adjuncts, adjoined higher in the structure, do not. For instance, in the argument structure "*[Which picture of John_i] did he_i like?", the possessive phrase "of John" reconstructs under movement, violating Principle C because the pronoun "he" c-commands the R-expression "John". In contrast, the adjunct example "[Which picture taken by John_i] did he_i like?" is grammatical, as the adjunct does not reconstruct, avoiding the c-command violation. This asymmetry holds experimentally, with arguments obligatorily reconstructing (mean acceptability rating 2.19) unlike adjuncts (3.24).[24] Movement tests further differentiate arguments by assessing their ability to undergo passivization or raising, operations that promote internal arguments to subject position while suppressing external ones. Arguments, as core complements, can shift positions without degradation, as in "The book was given to Mary" from "Someone gave the book to Mary", where "to Mary" (an indirect object argument) alternates with the subject in related constructions. Adjuncts resist such promotion; for example, "*Quickly was the race run by John" is ungrammatical, unlike the acceptable "The race was run quickly by John", because the manner adverb "quickly" cannot serve as the derived subject. Similarly, in VP-preposing, arguments must move with the verb ("*Draw a picture she did" is ill-formed), whereas adjuncts can remain in situ ("Leave on Monday she did"). These patterns confirm arguments' tighter integration into the verb's projection.[23] Coordination and scoping tests highlight behavioral differences in phrase combination and iteration. Arguments coordinate readily with other core phrases of the same type, as in "John studied French and German", where both are direct object arguments. Mixing an argument with an adjunct fails, yielding ungrammaticality like "*John studied French and last night". Adjuncts, however, coordinate easily among themselves and exhibit adverbial scoping, as in "John left in London and on Tuesday", where multiple locative/temporal adjuncts iterate without limit ("John left in London, on Tuesday, and quietly" is possible). Arguments resist such iteration; "*John saw the man the cookie" is impossible. These tests underscore adjuncts' looser, modifier-like attachment, allowing flexible stacking and scoping over the predicate.[25][23] Cross-linguistically, diagnostics like the stranding test in Germanic languages treat particles in verb-particle constructions as argument-like elements. In English and Dutch, objects can strand the particle under movement, as in "call the meeting off" becoming "the meeting, call off" in questions, indicating the particle occupies a position akin to a verbal argument rather than a peripheral adjunct. This stranding is unavailable for true adjunct prepositional phrases, which do not permit object extraction past them without island effects. Such behavior supports analyzing particles as integrated into the verb's argument structure across Germanic varieties.Arguments and Adjuncts in Noun Phrases

In noun phrases, arguments function as core participants essential to the semantic interpretation of the head noun, often realized through genitive constructions or prepositional phrases such as "of." For instance, in the phrase "the destruction of the city," the prepositional phrase "of the city" serves as an internal argument to the deverbal noun "destruction," specifying the theme affected by the event denoted by the noun.[9] This pattern is particularly evident in complex event nominalizations, where the noun inherits the argument structure from its verbal base, making such phrases obligatory for full semantic coherence.[9] In contrast, adjuncts in noun phrases provide additional, non-essential descriptive information and are typically optional modifiers, including attributive adjectives or adverbial prepositional phrases. Examples include "the old destruction of the city" (with "old" as an attributive adjective) or "the destruction in 1945 of the city" (with "in 1945" as a temporal adjunct).[26] These elements can be iterated or omitted without rendering the noun phrase semantically incomplete, distinguishing them from arguments through tests like optionality and iterability.[26] Relational nouns, such as "rivalry" or "mother," inherently denote binary or multi-participant relations and thus require arguments to express their full meaning, often via possessives or prepositions. In "the rivalry between the teams," the prepositional phrase "between the teams" realizes the relational arguments, which are obligatory for the noun's interpretive completeness.[27] Within nominalizations, arguments can vary in obligatoriness: eventive nominals like "examination of the students" demand their arguments (e.g., "of the students" as theme), while result nominals like "the examination" treat them as optional adjuncts.[9] Cross-linguistically, similar distinctions appear in relational adjectives, particularly in Romance languages, where they behave like arguments taking obligatory complements. In Spanish, the relational adjective "enemigo de" in phrases like "enemigo de Roma" (enemy of Rome) requires the "de"-phrase as an argument to specify the relational participant, akin to genitive arguments in English nominals.[28] This structure highlights how relational elements in noun phrases parallel verbal argumenthood, though adapted to nominal syntax.[29]Representation Methods

In Syntactic Frameworks

In syntactic frameworks, arguments are typically represented as structural sisters to predicates or in specifier positions within phrase structure trees, ensuring they directly saturate the valence requirements of the head. For instance, in verb phrases, core arguments like subjects and objects occupy complement or specifier slots adjacent to the verb, while adjuncts are adjoined to higher phrasal nodes, such as VP or IP levels, to modify without fulfilling subcategorization needs. This distinction maintains hierarchical organization, where arguments integrate into the core projection of the predicate, as seen in ditransitive constructions employing VP shells: the indirect object serves as a specifier in an inner vP, with the direct object as its complement, and the verb raising to a higher light verb head. X-bar theory formalizes this representation by positing that arguments saturate intermediate bar-level projections (X') of the head, forming the recursive backbone of phrases through complementation and specification. Complements, as arguments, attach as sisters to X' to complete the head's selectional properties, whereas adjuncts adjoin to X' or XP nodes, introducing optional modification without saturation. This binary structure—head with complement forming X', then specifier attaching to yield XP—ensures arguments are obligatory for well-formedness in argument-taking categories like V or N, distinguishing them from adjuncts that expand phrases peripherally. Dependency grammar, in contrast, eschews phrase-level embedding for a head-dependent relation, portraying arguments as primary dependents directly subordinated to the predicate to satisfy its valency. The predicate governs its arguments via labeled arcs indicating grammatical functions, such as subject or object, while adjuncts appear as secondary, peripheral dependents with looser attachment, often modifying via adverbial or circumstantial relations. This flatter structure highlights arguments' centrality to the dependency tree's core, with adjuncts branching outward to encode additional, non-essential information. In Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG), constituent structure (c-structure) trees explicitly annotate argument positions with functional equations, such as (↑ SUBJ) = ↓ for subjects in Spec-IP and (↑ OBJ) = ↓ for objects in complement-VP, linking surface form to abstract grammatical relations. These annotations ensure arguments map to f-structure slots like SUBJ or OBJ, distinguishing them from adjuncts labeled as ADJ, which adjoin without functional integration.[30] Similarly, the Minimalist Program enforces binary branching in Merge operations, positioning arguments in specifier or complement roles within extended projections, such as little-vP for external arguments and VP for internal ones, to derive theta-linked positions economically.[31]In Semantic Frameworks

In semantic frameworks, theta grids provide a lexical representation of a predicate's argument structure by specifying slots filled by arguments bearing particular theta roles, such as agent, theme, and goal.[15] For instance, the verb give is associated with a theta grid <agent, theme, goal>, where the agent initiates the action, the theme is transferred, and the goal receives it; this notation encodes the number and types of obligatory arguments required for semantic well-formedness. Theta grids also distinguish external arguments, typically mapped to the subject position and bearing roles like agent or experiencer, from internal arguments, which are objects within the verb phrase and often themes or patients.[15] Predicate logic formalizes arguments as variables bound by predicates or lambda operators, enabling precise composition of meaning.[32] In this approach, a sentence like "x eats y" is represented as , where and are argument variables denoting the eater and eaten, respectively, and lambda abstraction abstracts over these variables to form a functor that combines with actual noun phrases during interpretation.[33] This variable-binding mechanism ensures that arguments saturate predicate positions, contributing to the truth-conditional semantics of the sentence. Event semantics, particularly in the neo-Davidsonian framework, treats arguments as participants in events rather than direct complements of predicates, reifying events as entities with their own argument structure.[34] For example, the verb run is analyzed as , with the theme argument linked separately as , where is the event variable and the runner; this allows modifiers like adverbs to attach to the event while thematic relations specify participant roles.[35] Such representations facilitate the decomposition of complex sentences into atomic events and their arguments, supporting analyses of aspect and causation. Montague grammar employs compositional semantics where arguments occupy functor positions in a typed lambda calculus, ensuring that syntactic structure mirrors semantic combination.[33] Predicates act as higher-type functions that take arguments as inputs to yield truth values; for instance, a transitive verb like love is , applying first to the object argument to form a one-place predicate, then to the subject to complete the proposition.[32] This functor-argument application captures how quantified noun phrases, such as "every man," bind variables over argument slots, enabling scope resolution in sentences with multiple arguments.Theoretical Frameworks

Theta Theory and Argument Structure

Theta theory forms a core component of the Government and Binding (GB) framework in generative linguistics, regulating the assignment of semantic roles—known as theta roles—to syntactic arguments of a predicate. The theory's foundational principle is the Theta Criterion, which enforces a one-to-one bijection between the theta roles specified in a predicate's lexical entry and the arguments that saturate them in the sentence structure. This ensures that every argument receives exactly one theta role and that no theta role remains unassigned, preventing over- or under-generation in argument realization.[36] Complementing this is the Projection Principle, which mandates that lexical properties, including argument structures, project onto the deep structure (D-structure) and remain invariant through subsequent syntactic transformations, thereby linking thematic requirements directly to syntactic representation.[36] In GB theory, argument structure is represented lexically for each predicate, often involving decomposition into atomic semantic predicates to capture the verb's meaning and its required arguments. For instance, verbs like "break" can participate in alternations such as the causative-inchoative, where the transitive form ("John broke the window") introduces an external agent theta role alongside a theme, while the inchoative form ("The window broke") suppresses the agent, leaving only the theme. This alternation reflects systematic variations in argument realization, constrained by theta theory to maintain the bijection without violating subcategorization. Such decompositions highlight how lexical entries encode not just roles but also the predicate's event structure, influencing possible syntactic frames.[36][37] Theta grids provide a formal mechanism for constructing and representing argument structure, listing the theta roles a predicate assigns along with their hierarchical ordering and selectional restrictions. Typically, the agent role occupies the highest position in the hierarchy, followed by beneficiary or goal, experiencer, theme, and patient or instrument at lower levels, reflecting proto-agent and proto-patient properties that guide linking to syntactic positions. Assignment occurs at D-structure under government by the predicate, subject to the visibility condition: a chain must bear a Case feature to be visible for theta-marking, ensuring that only Case-bearing nominals can receive roles. For example, the theta grid for the verb "give" might specify an agent (external argument), a theme (direct object), and a goal (indirect object), as illustrated below:| Theta Role | Obligatory? | Hierarchical Position |

|---|---|---|

| Agent | Yes | 1 (highest) |

| Theme | Yes | 2 |

| Goal | Yes | 3 |