Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2-(4-Amidinophenyl)-1H-indole-6-carboxamidine

| |

| Other names

4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C16H15N5 | |

| Molar mass | 277.331 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

DAPI (pronounced 'DAPPY', /ˈdæpiː/), or 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, is a fluorescent stain that binds strongly to adenine–thymine-rich regions in DNA. It is used extensively in fluorescence microscopy. As DAPI can pass through an intact cell membrane, it can be used to stain both live and fixed cells, though it passes through the membrane less efficiently in live cells and therefore provides a marker for membrane viability.

History

[edit]DAPI was first synthesised in 1971 in the laboratory of Otto Dann as part of a search for drugs to treat trypanosomiasis. Although it was unsuccessful as a drug, further investigation indicated it bound strongly to DNA and became more fluorescent when bound. This led to its use in identifying mitochondrial DNA in ultracentrifugation in 1975, the first recorded use of DAPI as a fluorescent DNA stain.[1]

Strong fluorescence when bound to DNA led to the rapid adoption of DAPI for fluorescent staining of DNA for fluorescence microscopy. Its use for detecting DNA in plant, metazoa and bacteria cells and virus particles was demonstrated in the late 1970s, and quantitative staining of DNA inside cells was demonstrated in 1977. Use of DAPI as a DNA stain for flow cytometry was also demonstrated around this time.[1]

When bound to double-stranded DNA, DAPI has an absorption maximum at a wavelength of 358 nm (ultraviolet) and its emission maximum is at 461 nm (blue). Therefore, for fluorescence microscopy, DAPI is excited with ultraviolet light and is detected through a blue/cyan filter. The emission peak is fairly broad.[2] DAPI will also bind to RNA, though it is not as strongly fluorescent. Its emission shifts to around 500 nm when bound to RNA.[3][4]

DAPI's blue emission is convenient for microscopists who wish to use multiple fluorescent stains in a single sample. There is some fluorescence overlap between DAPI and green-fluorescent molecules like fluorescein and green fluorescent protein (GFP) but the effect of this is small.

Outside of analytical fluorescence light microscopy DAPI is also popular for labeling of cell cultures to detect the DNA of contaminating Mycoplasma or virus. The labelled Mycoplasma or virus particles in the growth medium fluoresce once stained by DAPI making them easy to detect.[5]

Modelling of absorption and fluorescence properties

[edit]This DNA fluorescent probe has been effectively modeled[6] using the time-dependent density functional theory, coupled with the IEF version of the polarizable continuum model. This quantum-mechanical modeling has rationalized the absorption and fluorescence behavior given by minor groove binding and intercalation in the DNA pocket, in term of a reduced structural flexibility and polarization.

Live cells and toxicity

[edit]DAPI can be used for fixed cell staining. The concentration of DAPI needed for live cell staining is generally very high; it is rarely used for live cells.[7] It is labeled non-toxic in its MSDS[8] and though it was not shown to have mutagenicity to E. coli,[9] it is labelled as a known mutagen in manufacturer information.[2] As it is a small DNA binding compound, it is likely to have some carcinogenic effects and care should be taken in its handling and disposal.

Alternatives

[edit]

The Hoechst stains are similar to DAPI in that they are also blue-fluorescent DNA stains which are compatible with both live- and fixed-cell applications, as well as visible using the same equipment filter settings as for DAPI.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Kapuscinski, J. (September 1995). "DAPI: a DNA-specific fluorescent probe". Biotech. Histochem. 70 (5): 220–233. doi:10.3109/10520299509108199. PMID 8580206.

- ^ a b Invitrogen, DAPI Nucleic Acid Stain Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine. accessed 2009-12-08.

- ^ Scott Prahl, DAPI. accessed 2009-12-08.

- ^ Kapuscinski, J (2017). "Interactions of nucleic acids with fluorescent dyes: spectral properties of condensed complexes". Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry. 38 (9): 1323–1329. doi:10.1177/38.9.1696951. PMID 1696951.

- ^ Russell, W. C.; Newman, Carol; Williamson, D. H. (1975). "A simple cytochemical technique for demonstration of DNA in cells infected with mycoplasmas and viruses". Nature. 253 (5491): 461–462. Bibcode:1975Natur.253..461R. doi:10.1038/253461a0. PMID 46112. S2CID 25224870.

- ^ Biancardi, Alessandro; Biver, Tarita; Secco, Fernando; Mennucci, Benedetta (2013). "An investigation of the photophysical properties of minor groove bound and intercalated DAPI through quantum-mechanical and spectroscopic tools". Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15 (13): 4596–603. Bibcode:2013PCCP...15.4596B. doi:10.1039/C3CP44058C. PMID 23423468.

- ^ Zink D, Sadoni N, Stelzer E (2003). "Visualizing Chromatin and Chromosomes in Living Cells. Usually for the live cells staining Hoechst Staining is used. DAPI gives a higher signal in the fixed cells compare to Hoechst Stain but in the live cells Hoechst Stain is used". Methods. 29 (1): 42–50. doi:10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00289-X. PMID 12543070.

- ^ DAPI MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET. kpl.com

- ^ Ohta T, Tokishita S, Yamagata H (2001). "Ethidium bromide and SYBR Green I enhance the genotoxicity of UV-irradiation and chemical mutagens in E. coli". Mutat. Res. 492 (1–2): 91–7. Bibcode:2001MRGTE.492...91O. doi:10.1016/S1383-5718(01)00155-3. PMID 11377248.

See also

[edit]Chemical Properties

Molecular Structure

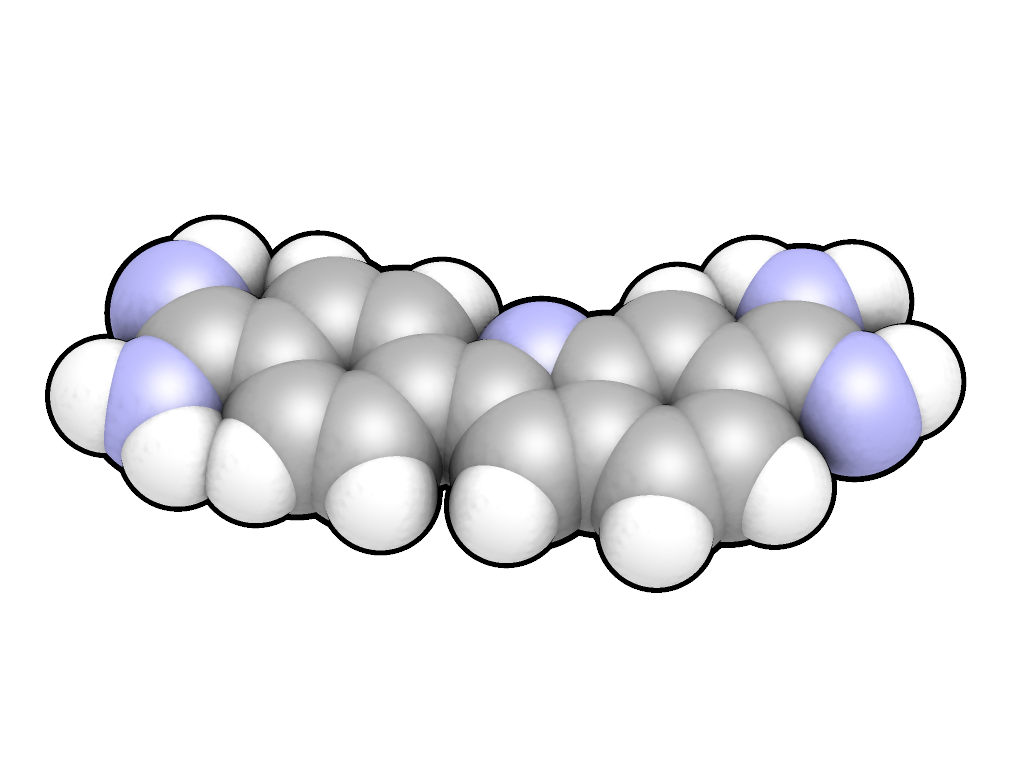

DAPI, chemically known as 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, has the molecular formula CHN in its free base form. The most commonly utilized variant is the dihydrochloride salt, with the formula CHN·2HCl and a molecular weight of 350.25 g/mol, which offers enhanced solubility in aqueous media compared to the neutral free base.[7][2] The molecular structure consists of a bicyclic indole core—a benzene ring fused to a pyrrole ring—with a phenyl substituent attached at the 2-position of the indole and two amidine groups (-C(=NH)NH) positioned at the 4' site on the phenyl ring and the 6 site on the indole's benzene moiety. This arrangement forms a conjugated aromatic system, often described as having a biphenyl-like core due to the connected ring systems. The molecule lacks stereocenters and is achiral, exhibiting a predominantly planar conformation that facilitates its interactions in biological contexts.[7][8] Crystal structures of DAPI-DNA complexes, such as the one in PDB entry 432D (d(GGCCAATTGG) at 1.9 Å resolution), reveal DAPI as a flat aromatic entity with slight deviations from perfect planarity. These structures show the coplanar orientation of the indole and phenyl rings, essential for the molecule's rigidity.[9][8] The hydrochloride salt form is preferred in laboratory settings due to its superior water solubility (up to 20 mg/mL with heating) over the free base, which exhibits limited aqueous solubility and often requires organic solvents like DMSO or ethanol for dissolution. This difference arises from the protonation of the amidine groups in the salt, increasing hydrophilicity.[2][10]Synthesis

The original synthesis of DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was reported by Dann et al. in 1971 as part of efforts to develop trypanosomicidal agents.[3] Modern synthesis of DAPI and its analogues typically involves the protection of 5(6)-cyanoindoles, lithiation to form stannanes, Stille coupling with bromoaryl/heteroaryl benzonitriles to yield bisnitriles, and subsequent amidine formation using lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide followed by deprotection with ethanolic HCl. These methods provide good yields (e.g., 61-75%) and are used to explore antitrypanosomal activity and DNA binding properties.[11] Purification of DAPI is commonly achieved through column chromatography on silica gel using methanol-chloroform mixtures as eluents, followed by recrystallization from ethanol or water to obtain the dihydrochloride salt. Characterization involves ^1H NMR spectroscopy to confirm the aromatic and amidine protons, mass spectrometry showing the molecular ion at m/z 278 for the free base, and melting point determination of the dihydrochloride at >300°C (decomposition). These methods ensure high purity (>98%) suitable for fluorescence applications.Spectroscopic Properties

Absorption and Emission Spectra

DAPI in aqueous solution displays an absorption maximum at approximately 340 nm in the ultraviolet region and an emission maximum at 488 nm, characterized by a molar absorptivity (ε) of about 23,000 M⁻¹ cm⁻¹ at 342 nm.[12] The quantum yield of unbound DAPI remains low, typically around 0.02–0.04, reflecting its weak fluorescence in free form due to efficient non-radiative decay pathways.[13] This spectral profile positions DAPI as a UV-excitable probe suitable for fluorescence microscopy, though its inherent dimness limits utility without nucleic acid binding. Upon binding to double-stranded DNA, particularly in AT-rich regions, DAPI undergoes a red shift in its absorption spectrum to 358–364 nm, while the emission maximum blue-shifts to 454–461 nm.[14][2] This interaction results in a dramatic 20-fold enhancement in fluorescence intensity, driven by an increase in quantum yield to about 0.6, alongside a Stokes shift of roughly 90–120 nm that facilitates effective separation of excitation and emission wavelengths in imaging applications.[15][13] These changes underscore the probe's sensitivity to its microenvironment, with binding-induced rigidity suppressing quenching mechanisms. The spectral characteristics of DAPI are influenced by environmental factors, including solvent polarity and pH. In organic media such as dimethyl sulfoxide, DAPI exhibits solvatochromic shifts, with higher quantum yields (up to 0.58) and altered emission profiles compared to aqueous conditions, highlighting its responsiveness to hydrophobic environments.[16] Fluorescence is optimally observed at neutral pH values of 7–8, where protonation states favor DNA binding and emission efficiency; deviations, such as acidic conditions, can diminish intensity by altering the dye's charge and solubility.[17][18]Fluorescence Mechanism

DAPI fluorescence arises from the absorption of ultraviolet (UV) photons by free DAPI at around 340 nm, which excites the molecule via a π-π* transition within its conjugated indolic and phenyl ring system. This process promotes an electron from the ground singlet state (S₀) to the lowest excited singlet state (S₁), as described in a simplified Jablonski diagram where intersystem crossing to the triplet state (T₁) is minimal due to the molecule's structure. In the free state, rapid non-radiative decay from S₁ to S₀ predominates through vibrational relaxation and internal conversion, resulting in weak fluorescence with a quantum yield of approximately 0.02.[19][1] Upon binding to the minor groove of DNA, particularly in AT-rich regions, the fluorescence intensity increases dramatically, up to 20-fold (with absorption shifting to ~358 nm and emission to ~461 nm), due to the restriction of intramolecular rotations and torsional motions around the phenyl-indole bond. This binding enforces a more planar conformation of the DAPI molecule, reducing non-radiative quenching pathways such as twisted intramolecular charge transfer (TICT) and collisional deactivation. The apolar microenvironment of the DNA minor groove further stabilizes the excited state by limiting solvent interactions that promote deactivation in aqueous solution.[19][20] Theoretical modeling using time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) has elucidated the excited-state properties, revealing that the absorption energies are highly sensitive to the binding environment, while emission energies remain relatively consistent. Calculations indicate a HOMO-LUMO gap of approximately 3.5 eV for the free DAPI molecule, aligning with the observed UV absorption and corresponding to the energy of the π-π* transition. These models confirm that DNA binding alters the electronic distribution, with charge displacement toward the amidine groups in the excited state, enhancing radiative decay.[19] Regarding photostability, DAPI undergoes photobleaching under prolonged UV excitation in microscopy, primarily through photoconversion and oxidative damage, with half-lives on the order of minutes under intense illumination conditions. For instance, significant bleaching occurs after 3 minutes of continuous UV exposure in standard setups, limiting prolonged imaging without antifade agents.[4]Simplified Jablonski Diagram for DAPI Fluorescence

S₁ (π-π* excited state) ──→ Fluorescence emission (488 nm, free; ~461 nm bound)

│

│ (Reduced non-radiative decay upon DNA binding)

▼

S₀ (Ground state) ←─── UV absorption (340 nm, free; ~358 nm bound)

│

└─ Non-radiative decay (dominant in free DAPI)

Simplified Jablonski Diagram for DAPI Fluorescence

S₁ (π-π* excited state) ──→ Fluorescence emission (488 nm, free; ~461 nm bound)

│

│ (Reduced non-radiative decay upon DNA binding)

▼

S₀ (Ground state) ←─── UV absorption (340 nm, free; ~358 nm bound)

│

└─ Non-radiative decay (dominant in free DAPI)