Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cytogenetics

View on Wikipedia

Cytogenetics is essentially a branch of genetics, but is also a part of cell biology/cytology (a subdivision of human anatomy), that is concerned with how the chromosomes relate to cell behaviour, particularly to their behaviour during mitosis and meiosis.[1] Techniques used include karyotyping, analysis of G-banded chromosomes, other cytogenetic banding techniques, as well as molecular cytogenetics such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH).

History

[edit]Beginnings

[edit]Chromosomes were first observed in plant cells by Carl Nägeli in 1842. Their behavior in animal (salamander) cells was described by Walther Flemming, the discoverer of mitosis, in 1882. The name was coined by another German anatomist, von Waldeyer in 1888.

The next stage took place after the development of genetics in the early 20th century, when it was appreciated that the set of chromosomes (the karyotype) was the carrier of the genes. Levitsky seems to have been the first to define the karyotype as the phenotypic appearance of the somatic chromosomes, in contrast to their genic contents.[2][3] Investigation into the human karyotype took many years to settle the most basic question: how many chromosomes does a normal diploid human cell contain?[4] In 1912, Hans von Winiwarter reported 47 chromosomes in spermatogonia and 48 in oogonia, concluding an XX/XO sex determination mechanism.[5] Painter in 1922 was not certain whether the diploid number of humans was 46 or 48, at first favoring 46.[6] He revised his opinion later from 46 to 48, and he correctly insisted on humans having an XX/XY system of sex-determination.[7] Considering their techniques, these results were quite remarkable. In science books, the number of human chromosomes remained at 48 for over thirty years. New techniques were needed to correct this error. Joe Hin Tjio working in Albert Levan's lab[8][9] was responsible for finding the approach:

- Using cells in culture

- Pre-treating cells in a hypotonic solution, which swells them and spreads the chromosomes

- Arresting mitosis in metaphase by a solution of colchicine

- Squashing the preparation on the slide forcing the chromosomes into a single plane

- Cutting up a photomicrograph and arranging the result into an indisputable karyogram.

It took until 1956 for it to be generally accepted that the karyotype of man included only 46 chromosomes.[10][11][12] The great apes have 48 chromosomes. Human chromosome 2 was formed by a merger of ancestral chromosomes, reducing the number.[13]

Applications of cytogenetics

[edit]McClintock's work on maize

[edit]Barbara McClintock began her career as a maize cytogeneticist. In 1931, McClintock and Harriet Creighton demonstrated that cytological recombination of marked chromosomes correlated with recombination of genetic traits (genes). McClintock, while at the Carnegie Institution, continued previous studies on the mechanisms of chromosome breakage and fusion flare in maize. She identified a particular chromosome breakage event that always occurred at the same locus on maize chromosome 9, which she named the "Ds" or "dissociation" locus.[14] McClintock continued her career in cytogenetics studying the mechanics and inheritance of broken and ring (circular) chromosomes of maize. During her cytogenetic work, McClintock discovered transposons, a find which eventually led to her Nobel Prize in 1983.

Natural populations of Drosophila

[edit]In the 1930s, Dobzhansky and his coworkers collected Drosophila pseudoobscura and D. persimilis from wild populations in California and neighboring states. Using Painter's technique[15] they studied the polytene chromosomes and discovered that the wild populations were polymorphic for chromosomal inversions. All the flies look alike whatever inversions they carry: this is an example of a cryptic polymorphism.[citation needed]

Evidence rapidly accumulated to show that natural selection was responsible. Using a method invented by L'Héritier and Teissier, Dobzhansky bred populations in population cages, which enabled feeding, breeding and sampling whilst preventing escape. This had the benefit of eliminating migration as a possible explanation of the results. Stocks containing inversions at a known initial frequency can be maintained in controlled conditions. It was found that the various chromosome types do not fluctuate at random, as they would if selectively neutral, but adjust to certain frequencies at which they become stabilised. By the time Dobzhansky published the third edition of his book in 1951[16] he was persuaded that the chromosome morphs were being maintained in the population by the selective advantage of the heterozygotes, as with most polymorphisms.[17][18]

Lily and mouse

[edit]The lily is a favored organism for the cytological examination of meiosis since the chromosomes are large and each morphological stage of meiosis can be easily identified microscopically. Hotta, Chandley et al.[19] presented the evidence for a common pattern of DNA nicking and repair synthesis in male meiotic cells of lilies and rodents during the zygotene–pachytene stages of meiosis when crossing over was presumed to occur. The presence of a common pattern between organisms as phylogenetically distant as lily and mouse led the authors to conclude that the organization for meiotic crossing-over in at least higher eukaryotes is probably universal in distribution.[citation needed]

Human abnormalities and medical applications

[edit]

Following the advent of procedures that allowed easy enumeration of chromosomes, discoveries were quickly made related to aberrant chromosomes or chromosome number.[citation needed]

Constitutional cytogenetics: In some congenital disorders, such as Down syndrome, cytogenetics revealed the nature of the chromosomal defect: a "simple" trisomy. Abnormalities arising from nondisjunction events can cause cells with aneuploidy (additions or deletions of entire chromosomes) in one of the parents or in the fetus. In 1959, Lejeune[20] discovered patients with Down syndrome had an extra copy of chromosome 21. Down syndrome is also referred to as trisomy 21.

Other numerical abnormalities discovered include sex chromosome abnormalities. A female with only one X chromosome has Turner syndrome, whereas a male with an additional X chromosome, resulting in 47 total chromosomes, has Klinefelter syndrome. Many other sex chromosome combinations are compatible with live birth including XXX, XYY, and XXXX. The ability for mammals to tolerate aneuploidies in the sex chromosomes arises from the ability to inactivate them, which is required in normal females to compensate for having two copies of the chromosome. Not all genes on the X chromosome are inactivated, which is why there is a phenotypic effect seen in individuals with extra X chromosomes.[citation needed]

Trisomy 13 was associated with Patau syndrome and trisomy 18 with Edwards syndrome.[citation needed]

Acquired cytogenetics: In 1960, Peter Nowell and David Hungerford[21] discovered a small chromosome in the white blood cells of patients with Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). This abnormal chromosome was dubbed the Philadelphia chromosome - as both scientists were doing their research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Thirteen years later, with the development of more advanced techniques, the abnormal chromosome was shown by Janet Rowley to be the result of a translocation of chromosomes 9 and 22. Identification of the Philadelphia chromosome by cytogenetics is diagnostic for CML. More than 780 leukemias and hundreds of solid tumors (lung, prostate, kidney, etc.) are now characterized by an acquired chromosomal abnormality, whose prognostic value is crucial. The identification of these chromosomal abnormalities has led to the discovery of a very large number of "cancer genes" (or oncogenes). The increasing knowledge of these cancer genes now allows the development of targeted therapies, which transforms the prospects of patient survival. Thus, cytogenetics has had and continues to have an essential role in the progress of cancer understanding. Large databases (Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology, COSMIC cancer database, Mitelman Database of Chromosome Aberrations and Gene Fusions in Cancer) allow researchers and clinicians to have the necessary corpus for their work in this field.

Advent of banding techniques

[edit]

In the late 1960s, Torbjörn Caspersson developed a quinacrine fluorescent staining technique (Q-banding) which revealed unique banding patterns for each chromosome pair. This allowed chromosome pairs of otherwise equal size to be differentiated by distinct horizontal banding patterns. Banding patterns are now used to elucidate the breakpoints and constituent chromosomes involved in chromosome translocations. Deletions and inversions within an individual chromosome can also be identified and described more precisely using standardized banding nomenclature. G-banding (utilizing trypsin and Giemsa/ Wright stain) was concurrently developed in the early 1970s and allows visualization of banding patterns using a bright field microscope.[citation needed]

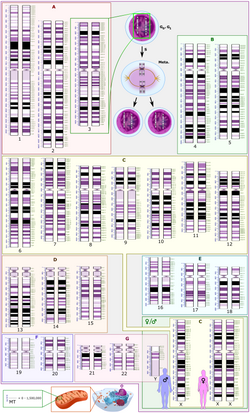

Diagrams identifying the chromosomes based on the banding patterns are known as idiograms. These maps became the basis for both prenatal and oncological fields to quickly move cytogenetics into the clinical lab where karyotyping allowed scientists to look for chromosomal alterations. Techniques were expanded to allow for culture of free amniocytes recovered from amniotic fluid, and elongation techniques for all culture types that allow for higher-resolution banding.[citation needed]

Beginnings of molecular cytogenetics

[edit]In the 1980s, advances were made in molecular cytogenetics. While radioisotope-labeled probes had been hybridized with DNA since 1969, movement was now made in using fluorescent-labeled probes. Hybridizing them to chromosomal preparations using existing techniques came to be known as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).[22] This change significantly increased the usage of probing techniques as fluorescent-labeled probes are safer. Further advances in micromanipulation and examination of chromosomes led to the technique of chromosome microdissection whereby aberrations in chromosomal structure could be isolated, cloned, and studied in ever greater detail.[citation needed]

Techniques

[edit]Karyotyping

[edit]The routine chromosome analysis (Karyotyping) refers to analysis of metaphase chromosomes which have been banded using trypsin followed by Giemsa, Leishmanns, or a mixture of the two. This creates unique banding patterns on the chromosomes. The molecular mechanism and reason for these patterns are unknown, although it's likely related to replication timing and chromatin packing.[citation needed]

Several chromosome-banding techniques are used in cytogenetics laboratories. Quinacrine banding (Q-banding) was the first staining method used to produce specific banding patterns. This method requires a fluorescence microscope and is no longer as widely used as Giemsa banding (G-banding). Reverse banding, or R-banding, requires heat treatment and reverses the usual black-and-white pattern that is seen in G-bands and Q-bands. This method is particularly helpful for staining the distal ends of chromosomes. Other staining techniques include C-banding and nucleolar organizing region stains (NOR stains). These latter methods specifically stain certain portions of the chromosome. C-banding stains the constitutive heterochromatin, which usually lies near the centromere, and NOR staining highlights the satellites and stalks of acrocentric chromosomes.[citation needed]

High-resolution banding involves the staining of chromosomes during prophase or early metaphase (prometaphase), before they reach maximal condensation. Because prophase and prometaphase chromosomes are more extended than metaphase chromosomes, the number of bands observable for all chromosomes (bands per haploid set, bph; "band level") increases from about 300 to 450 to as many as 800. This allows the detection of less obvious abnormalities usually not seen with conventional banding.[23]

Slide preparation

[edit]Cells from bone marrow, blood, amniotic fluid, cord blood, tumor, and tissues (including skin, umbilical cord, chorionic villi, liver, and many other organs) can be cultured using standard cell culture techniques in order to increase their number. A mitotic inhibitor (colchicine, colcemid) is then added to the culture. This stops cell division at mitosis which allows an increased yield of mitotic cells for analysis. The cells are then centrifuged and media and mitotic inhibitor are removed, and replaced with a hypotonic solution. This causes the white blood cells or fibroblasts to swell so that the chromosomes will spread when added to a slide as well as lyses the red blood cells. After the cells have been allowed to sit in hypotonic solution, Carnoy's fixative (3:1 methanol to glacial acetic acid) is added. This kills the cells and hardens the nuclei of the remaining white blood cells. The cells are generally fixed repeatedly to remove any debris or remaining red blood cells. The cell suspension is then dropped onto specimen slides. After aging the slides in an oven or waiting a few days they are ready for banding and analysis.

Analysis

[edit]Analysis of banded chromosomes is done at a microscope by a clinical laboratory specialist in cytogenetics (CLSp(CG)). Generally 20 cells are analyzed which is enough to rule out mosaicism to an acceptable level. The results are summarized and given to a board-certified cytogeneticist for review, and to write an interpretation taking into account the patient's previous history and other clinical findings. The results are then given out reported in an International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature 2009 (ISCN2009)..

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

[edit]

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) refers to using fluorescently labeled probe to hybridize to cytogenetic cell preparations.

In addition to standard preparations FISH can also be performed on:

- bone marrow smears

- blood smears

- paraffin embedded tissue preparations

- enzymatically dissociated tissue samples

- uncultured bone marrow

- uncultured amniocytes

- Cytospin preparations

Slide preparation

[edit]This section refers to the preparation of standard cytogenetic preparations

The slide is aged using a salt solution usually consisting of 2X SSC (salt, sodium citrate). The slides are then dehydrated in ethanol, and the probe mixture is added. The sample DNA and the probe DNA are then co-denatured using a heated plate and allowed to re-anneal for at least 4 hours. The slides are then washed to remove the excess unbound probe, and counterstained with 4',6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) or propidium iodide.

Analysis

[edit]Analysis of FISH specimens is done by fluorescence microscopy by a clinical laboratory specialist in cytogenetics. For oncology, generally, a large number of interphase cells are scored in order to rule out low-level residual disease, generally between 200 and 1,000 cells are counted and scored. For congenital problems usually 20 metaphase cells are scored.[citation needed]

Future of cytogenetics

[edit]Advances now focus on molecular cytogenetics including automated systems for counting the results of standard FISH preparations and techniques for virtual karyotyping, such as comparative genomic hybridization arrays, CGH and Single nucleotide polymorphism arrays.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Rieger, R.; Michaelis, A.; Green, M.M. (1968), A glossary of genetics and cytogenetics: Classical and molecular, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-07668-3

- ^ Levitsky, Grigorii Andreevich (1924). Material'nye osnovy nasledstvennosti [The Material Basis of Heredity] (in Russian). Kiev: Gosizdat Ukrainy.[page needed]

- ^ Levitsky GA (1931). "The morphology of chromosomes". Bull. Applied Bot. Genet. Plant Breed. 27: 19–174.

- ^ Kottler, Malcolm Jay (1974). "From 48 to 46: cytological technique, preconception, and the counting of human chromosomes". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 48 (4): 465–502. JSTOR 44450164. PMID 4618149. ProQuest 1296285397.

- ^ von Winiwarter H (1912). "Études sur la spermatogenese humaine" [Human spermatogenesis studies]. Arch. Biologie (in French). 27 (93): 147–149.

- ^ Painter T.S. "The spermatogenesis of man" p. 129 in "Abstracts". The Anatomical Record. 23 (1): 89–132. January 1922. doi:10.1002/ar.1090230111.

- ^ Painter, Theophilus S. (April 1923). "Studies in mammalian spermatogenesis. II. The spermatogenesis of man". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 37 (3): 291–336. Bibcode:1923JEZ....37..291P. doi:10.1002/jez.1400370303.

- ^ Wright, Pearce (11 December 2001). "Joe Hin Tjio The man who cracked the chromosome count". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017.

- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang (7 December 2001). "Joe Hin Tjio, 82; Research Biologist Counted Chromosomes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013.

- ^ Tjio, Joe Hin; Levan, Albert (9 July 2010). "The chromosome number of man". Hereditas. 42 (1–2): 723–4. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5223.1956.tb03010.x. PMID 345813.

- ^ Hsu, T. C. (2012). Human and Mammalian Cytogenetics: An Historical Perspective. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4612-6159-9.[page needed]

- ^ "Human genetics (Biology) :: The human chromosomes -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 2011-02-17. Retrieved 2011-03-15. Encyclopædia Britannica, The Human Chromosome

- ^ "Chromosome fusion". Archived from the original on 2011-08-09. Retrieved 2010-05-29. Evolution Pages, Chromosome fusion

- ^ Ravindran, Sandeep (11 December 2012). "Barbara McClintock and the discovery of jumping genes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (50): 20198–20199. doi:10.1073/pnas.1219372109. PMC 3528533. PMID 23236127.

- ^ Painter, T. S. (22 December 1933). "A new method for the study of chromosome rearrangements and the plotting of chromosome maps". Science. 78 (2034): 585–586. Bibcode:1933Sci....78..585P. doi:10.1126/science.78.2034.585. PMID 17801695.

- ^ Dobzhansky T. 1951. Genetics and the origin of species. 3rd ed, Columbia University Press, New York.

- ^ Dobzhansky T. 1970. Genetics of the evolutionary process. Columbia University Press N.Y.

- ^ [Dobzhansky T.] 1981. Dobzhansky's genetics of natural populations. eds Lewontin RC, Moore JA, Provine WB and Wallace B. Columbia University Press N.Y.

- ^ Hotta, Yasuo; Chandley, Ann C.; Stern, Herbert (September 1977). "Meiotic crossing-over in lily and mouse". Nature. 269 (5625): 240–242. Bibcode:1977Natur.269..240H. doi:10.1038/269240a0. PMID 593319. S2CID 4268089.

- ^ Lejeune, Jérôme; Gautier, Marthe; Turpin, Raymond (16 March 1959). "Étude des chromosomes somatiques des neuf enfants mongoliens" [Study of somatic chromosomes from 9 mongoloid children]. Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). 248 (11): 1721–1722. OCLC 871332352. PMID 13639368. NAID 10008406728.

- ^ Nowell PC, Hungerford DA. "A minute chromosome in human chronic granulocytic leukemia". pp. 1497–1501 in "National Academy of Sciences". Science. 132 (3438): 1488–1501. 18 November 1960. doi:10.1126/science.132.3438.1488. PMID 17739576.

- ^ Gupta, P. K. (2007). Cytogenetics. Rastogi Publications. ISBN 978-81-7133-737-8.[page needed]

- ^ Geiersbach, Katherine B.; Gardiner, Anna E.; Wilson, Andrew; Shetty, Shashirekha; Bruyère, Hélène; Zabawski, James; Saxe, Debra F.; Gaulin, Rebecca; Williamson, Cynthia; Van Dyke, Daniel L. (February 2014). "Subjectivity in chromosome band–level estimation: a multicenter study". Genetics in Medicine. 16 (2): 170–175. doi:10.1038/gim.2013.95. PMID 23887773.

External links

[edit]- Cytogenetic Directory

- Cytogenetics Resources Archived 2017-05-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Human Cytogenetics - Chromosomes and Karyotypes

- Association for Genetic Technologists

- Association of Clinical Cytogeneticists

- Gladwin Medical Blog Archived 2006-11-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Cytogenetics - Technologies,markets and companies

- Cytogenetics-methods-and-trouble-shooting

- Department of Cytogenetics of Wikiversity