Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

British blues

View on Wikipedia| British blues | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Mid-twentieth-century United Kingdom |

| Derivative forms |

|

| Fusion genres | |

British blues is a form of music derived from American blues that originated in the late 1950s, and reached its height of mainstream popularity in the 1960s. In Britain, blues developed a distinctive and influential style dominated by electric guitar, and made international stars of several proponents of the genre, including the Rolling Stones, the Animals, the Yardbirds, John Mayall, Eric Clapton, Fleetwood Mac and Led Zeppelin.

Origins

[edit]

American blues became known in Britain from the 1930s onwards through a number of routes, including records brought to Britain, particularly by African-American GIs stationed there in the Second World War and Cold War, merchant seamen visiting ports such as London, Liverpool, Newcastle upon Tyne and Belfast,[1] and through a trickle of (illegal) imports.[2] Blues music was relatively well known to British jazz musicians and fans, particularly in the works of figures like female singers Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith and the blues-influenced boogie-woogie of Jelly Roll Morton and Fats Waller.[2] From 1955 major British record labels His Master's Voice and EMI, the latter, particularly through their subsidiary Decca Records, began to distribute American jazz and increasingly blues records to what was an emerging market.[2] Many encountered blues for the first time through the skiffle craze of the second half of the 1950s, particularly the songs of Lead Belly covered by acts like Lonnie Donegan. As skiffle began to decline in the late 1950s, and British rock and roll began to dominate the charts, a number of skiffle musicians moved towards playing purely blues music.[3]

Among these were guitarist and blues harpist Cyril Davies, who ran the London Skiffle Club at the Roundhouse public house in London's Soho, and guitarist Alexis Korner, both of whom worked for jazz band leader Chris Barber, playing in the R&B segment he introduced to his show.[4] The club served as a focal point for British skiffle acts and Barber was responsible for bringing over American folk and blues performers, who found they were much better known and paid in Europe than America. The first major artist was Big Bill Broonzy, who visited England in the mid-1950s, but who, rather than his electric Chicago blues, played a folk blues set to fit in with British expectations of American blues as a form of folk music. In 1957 Davies and Korner decided that their central interest was the blues and closed the skiffle club, reopening a month later in the Roundhouse pub, Wardour Street, Soho as the London Blues and Barrelhouse Club.[5] To this point British blues was acoustically played emulating Delta blues and country blues styles and often part of the emerging second British folk revival. Critical in changing this was the visit of Muddy Waters in 1958, who initially shocked British audiences by playing amplified electric blues, but who was soon playing to ecstatic crowds and rave reviews.[4]

Davies and Korner, having already split with Barber, now plugged in and began to play high-powered electric blues that became the model for the subgenre, forming the band Blues Incorporated.[4] In early 1962, having been ejected from the Roundhouse for being too loud, Korner and Davies moved their club to the venue used by Ealing Jazz Club and on 17 March opened the UK's first regular UK blues night.

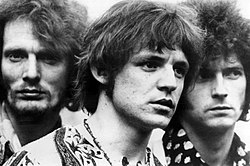

Blues Incorporated became something of a clearing house for British blues musicians in the later 1950s and early 1960s, with many joining, or sitting in on sessions. These included future Rolling Stones, Keith Richards, Mick Jagger, Charlie Watts and Brian Jones; as well as Cream founders Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker; beside Graham Bond and Long John Baldry.[4] After their success at the Ealing Club, Blues Incorporated were given a residency at the Marquee Club and it was from there that in 1962 they took the name of the first British blues album, R&B from the Marquee for Decca, but split before its release.[4] The culmination of this first movement of blues[6] came with John Mayall, who moved to London in the early 1960s, eventually forming the Bluesbreakers, whose members at various times included, Jack Bruce, Aynsley Dunbar, Eric Clapton, Peter Green and Mick Taylor.[4]

British rhythm and blues

[edit]While some bands focused on blues artists, particularly those of Chicago electric blues, others adopted a wider interest in rhythm and blues, including the work of Chess Records' blues artists like Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf, but also rock and roll pioneers Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley.[7] Most successful were the Rolling Stones, who abandoned blues purism before their line-up solidified and they produced their first eponymously titled album in 1964, which largely consisted of rhythm and blues standards. Following in the wake of the Beatles' national and then international success, the Rolling Stones soon established themselves as the second most popular UK band and joined the British Invasion of the American record charts as leaders of a second wave of R&B orientated bands.[7][8] In addition to Chicago blues numbers, the Rolling Stones covered songs by Chuck Berry and the Valentinos, with the latter's "It's All Over Now" giving them their first UK number one in 1964.[9] Blues songs and influences continued to surface in the Rolling Stones' music, as in their version of "Little Red Rooster", which went to number 1 on the UK singles chart in December 1964.[10]

Other London-based bands included the Yardbirds (whose ranks included three key guitarists in Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page), The Kinks (with pioneer songwriter Ray Davies and rock-guitarist Dave Davies),[8] and Manfred Mann (considered to have one of the most authentic sounding vocalists in the scene in Paul Jones) and the Pretty Things, beside the more jazz-influenced acts like the Graham Bond Organisation, Georgie Fame and Zoot Money.[7] Bands to emerge from other major British cities included the Animals from Newcastle (with the keyboards of Alan Price and vocals of Eric Burdon), the Moody Blues and Spencer Davis Group from Birmingham (the latter largely a vehicle for the young Steve Winwood), and Them from Belfast (with their vocalist Van Morrison).[7] None of these bands played exclusively rhythm and blues, often relying on a variety of sources, including Brill Building and girl group songs for their hit singles, but it remained at the core of their early albums.[7]

The British Mod subculture was musically centred on rhythm and blues and later soul music, performed by artists that were not available in small London clubs around which the scene was based.[11] As a result, a number of mod bands emerged to fill this gap. These included the Small Faces, The Creation, the Action and, most successfully, the Who.[11] The Who's early promotional material tagged them as producing "maximum rhythm and blues", but by about 1966 they moved from attempting to emulate American R&B to producing songs that reflected the Mod lifestyle.[11] Many of these bands were able to enjoy cult and then national success in the UK, but found it difficult to break into the American market.[11] Only the Who managed, after some difficulty, to produce a significant US following, particularly after their appearances at the Monterey Pop Festival (1967) and Woodstock (1969).[12]

Because of the very different circumstances from which they came, and in which they played, the rhythm and blues these bands produced was very different in tone from that of African American artists, often with more emphasis on guitars and sometimes with greater energy.[7] They have been criticised for exploiting the massive catalogue of African American music, but it has also been noted that they both popularised that music, bringing it to British, world and in some cases American audiences, and helping to build the reputation of existing and past rhythm and blues artists.[7] Most of these bands rapidly moved on from recording and performing American standards to writing and recording their own music, often leaving their R&B roots behind, but enabling several to enjoy sustained careers that were not open to most of the more pop-oriented beat groups of the first wave of the invasion, who (with the major exception of the Beatles) were unable to write their own material or adapt to changes in the musical climate.[7]

British blues boom

[edit]

The blues boom overlapped, both chronologically and in terms of personnel, with the earlier, wider rhythm and blues phase, which had begun to peter out in the mid-1960s leaving a nucleus of instrumentalists with a wide knowledge of blues forms and techniques, which they would carry into the pursuit of more purist blues interests.[13][14] Blues Incorporated and Mayall's Bluesbreakers were well known in the London jazz and emerging R&B circuits, but the Bluesbreakers began to gain some national and international attention, particularly after the release of Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton album (1966), considered one of the seminal British blues recordings.[15] Produced by Mike Vernon, who later set up the Blue Horizon record label, it was notable for its driving rhythms and Clapton's rapid blues licks with a full distorted sound derived from a Gibson Les Paul and a Marshall amp. This sound became something of a classic combination for British blues (and later rock) guitarists,[16] and also made clear the primacy of the guitar, seen as a distinctive characteristic of the subgenre.[4] Clapton stated, "I spent most of my teens and early twenties studying the blues—the geography of it and the chronology of it, as well as how to play it".[17] Peter Green started what is called "second great epoch of British blues",[6] as he replaced Clapton in the Bluesbreakers after his departure to form Cream. In 1967, after one record with the Bluesbreakers, Green, with the Bluesbreaker's rhythm section Mick Fleetwood and John McVie, formed Peter Green's Fleetwood Mac,[18] produced by Mike Vernon on the Blue Horizon label. One key factor in developing the popularity of the music in the UK and across Europe in the early 1960s was the success of the American Folk Blues Festival tours, organised by German promoters Horst Lippmann and Fritz Rau.[19]

The rise of electric blues, and its eventual mainstream success, meant that British acoustic blues was completely overshadowed. In the early 1960s, folk guitar pioneers Bert Jansch, John Renbourn and particularly Davy Graham (who played and recorded with Korner), played blues, folk and jazz, developing a distinctive guitar style known as folk baroque.[20] British acoustic blues continued to develop as part of the folk scene, with figures like Ian A. Anderson and his Country Blues Band,[21] and Al Jones.[22] Most British acoustic blues players could achieve little commercial success and, with a few exceptions, found it difficult to gain any recognition for their "imitations" of the blues in the US.[23]

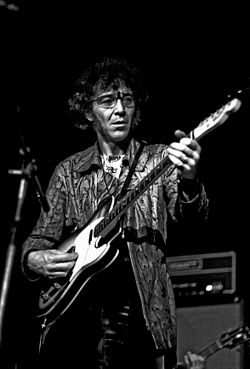

In contrast, the next wave of bands, formed from about 1967, like Cream, Fleetwood Mac, Ten Years After, Savoy Brown, and Free, pursued a different route, retaining blues standards in their repertoire and producing original material that often shied away from obvious pop influences, placing an emphasis on individual virtuosity.[24] The result has been characterised as blues rock and arguably marked the beginnings of a separation of pop and rock music that was to be a feature of the record industry for several decades.[24] Cream is often seen as the first supergroup, combining the talents of Clapton, Bruce and Baker;[25] they have also been seen as one of the first groups to exploit the power trio. Although only together for a little over two years in 1966–1969, they were highly influential and it was in this period that Clapton became an international superstar.[26] Fleetwood Mac are often considered to have produced some of the finest work in the subgenre, with inventive interpretations of Chicago blues.[4] They were also the most commercially successful group, with their eponymous début album reaching the UK top five in early 1968 and as the instrumental "Albatross" reached number one in the single charts in early 1969. This was, as Scott Schinder and Andy Schwartz put it, "The commercial apex of the British blues Boom".[27] Free, with the guitar talents of Paul Kossoff, particularly from their self titled second album (1969), produced a stripped down form of blues that would be highly influential on hard rock and later heavy metal.[28] Ten Years After, with guitarist Alvin Lee, formed in 1967, but achieved their breakthrough in 1968 with their live album Undead and in the US with their appearance at Woodstock the next year.[29] Among the last British blues bands to gain mainstream success were Jethro Tull, formed from the amalgamation of two blues bands, the John Evan Band and the Mcgregor's Engine in 1967. Their second album, Stand Up, reached number one in the UK in 1969.[30]

Decline

[edit]

British blues entered a rapid decline at the end of 1960s. Surviving bands and musicians tended to move into other expanding areas of rock music. Some, like Jethro Tull, followed bands like the Moody Blues away from 12-bar structures and harmonicas into complex, classical-influenced progressive rock.[31] Some played a loud version of blues rock that became the foundation for hard rock and heavy metal. Led Zeppelin, formed by Yardbirds guitarist Jimmy Page, on their first two albums, both released in 1969, fused heavy blues and amplified rock to create what has been seen as a watershed in the development of hard rock and nascent heavy metal.[32] Later recordings would mix in elements of folk and mysticism, which would also be a major influence on heavy metal music.[33] Deep Purple developed a sound based on "squeezing and stretching" the blues,[34] and achieved their commercial breakthrough with their fourth and distinctively heavier album, Deep Purple in Rock (1970), which has been seen as one of heavy metal's defining albums.[35] Black Sabbath was the third incarnation of a group that started as the Polka Tulk Blues Band in 1968. Their early work included blues standards, but by the time of their second album Paranoid (1970), they had added elements of modality and the occult that would largely define modern heavy metal.[36] Some, like Korner and Mayall, continued to play a "pure" form of the blues, but largely outside of mainstream notice. The structure of clubs, venues and festivals that had grown up in the early 1950s in Britain virtually disappeared in the 1970s.[37]

Survival and resurgence

[edit]

Although overshadowed by the growth of rock music the blues did not disappear in Britain, with American bluesmen such as John Lee Hooker, Eddie Taylor, and Freddie King continuing to be well received in the UK and an active home scene led by figures including Dave Kelly and his sister Jo Ann Kelly, who helped keep the acoustic blues alive on the British folk circuit.[38] Dave Kelly was also a founder of The Blues Band with former Manfred Mann members Paul Jones and Tom McGuinness, Hughie Flint and Gary Fletcher.[38] The Blues Band was credited with kicking off a second blues boom in Britain, which by the 1990s led to festivals all around the country, including The Swanage Blues Festival, The Burnley National Blues Festival, The Gloucester Blues and Heritage Festival and The Great British Rhythm and Blues Festival at Colne.[38] The twenty-first century has seen an upsurge in interest in the blues in Britain that can be seen in the success of previously unknown acts including Seasick Steve,[39] in the return to the blues by major figures who began in the first boom, including Peter Green,[40] Mick Fleetwood,[41] Chris Rea[42] and Eric Clapton,[43] as well as the arrival of new artists such as Dani Wilde. Nine Below Zero continue to fly the flag for British blues, as they have done for over 40 years, alongside Dr. Feelgood. Matt Schofield,[44] Aynsley Lister and most recently in 2017 the Starlite Campbell Band.[45] The British blues tradition lives on, as a style, outside of Britain as well. American guitarist Joe Bonamassa describes his main influences as the 1960s era British blues players, and considers himself a part of that tradition rather than the earlier American blues styles.[46]

Significance

[edit]Beside giving a start to many important blues, pop and rock musicians, in spawning blues rock British blues also ultimately gave rise to a host of subgenres of rock, including particularly psychedelic rock, progressive rock,[24] hard rock and ultimately heavy metal.[47] Perhaps the most important contribution of British blues was the surprising re-exportation of American blues back to America, where, in the wake of the success of bands like the Rolling Stones and Fleetwood Mac, white audiences began to look again at black blues musicians like Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf and John Lee Hooker, who suddenly began to appeal to middle class white Americans.[47] The result was a re-evaluation of the blues in America which enabled white Americans much more easily to become blues musicians, opening the door to Southern rock and the development of Texas blues musicians like Stevie Ray Vaughan.[4]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ R. F. Schwartz, How Britain Got the Blues: the Transmission and Reception of American Blues Style in the United Kingdom (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), ISBN 0-7546-5580-6, p. 28.

- ^ a b c R. F. Schwartz, How Britain Got the Blues: the Transmission and Reception of American Blues Style in the United Kingdom (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), p. 22.

- ^ M. Brocken, The British Folk Revival, 1944-2002 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), pp. 69-80.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra, S. T. Erlewine, eds, All Music Guide to the Blues: The Definitive Guide to the Blues (Backbeat, 3rd edn., 2003), p. 700.

- ^ L. Portis, Soul Trains (Virtualbookworm Publishing, 2002), p. 213.

- ^ a b Marshall, Wolf (September 2007). "Peter Green: The Blues of Greeny". Vintage Guitar. 21 (11): 96–100.

- ^ a b c d e f g h V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1315-6.

- ^ a b Gilliland 1969, show 38.

- ^ Bill Wyman, Rolling With the Stones (DK Publishing, 2002), ISBN 0-7894-9998-3, p. 137.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "Rolling Stones", Allmusic, retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ a b c d V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1321-2.

- ^ B. Eder & S. T. Erlewine, "The Who", Allmusic, retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ R. Unterberger, "Early British R&B", in V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1315-6.

- ^ N. Logan and B. Woffinden, The NME Book of Rock 2 (London: W. H. Allen, 1977), ISBN 0-352-39715-2, pp. 61-2.

- ^ T. Rawlings, A. Neill, C. Charlesworth and C. White, Then, Now and Rare British Beat 1960–1969 (Omnibus Press, 2002), p. 130.

- ^ M. Roberty and C. Charlesworth, The Complete Guide to the Music of Eric Clapton (Omnibus Press, 1995), p. 11.

- ^ Du Noyer, Paul (2003). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Music (1st ed.). Fulham, London: Flame Tree Publishing. p. 172. ISBN 1-904041-96-5.

- ^ R. Brunning, The Fleetwood Mac Story: Rumours and Lies (Omnibus Press, 2004), pp. 1–15.

- ^ Schwartz, Roberta Freund (5 September 2007). How Britain Got the Blues: The Transmission and Reception of American Blues Style in the United Kingdom. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 212. ISBN 9780754655800. Retrieved 5 September 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford University Press, 2005) pp. 184–189.

- ^ "Ian A. Anderson[permanent dead link]", NME Artists, retrieved 23/06/09.

- ^ "Al Jones: acoustic blues and folk musician", Times Online 20/08/08, retrieved 23/06/09.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford University Press, 2005) p. 252.

- ^ a b c D. Hatch and S. Millward, From Blues to Rock: an Analytical History of Pop Music (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987), p. 105.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 53.

- ^ R. Unterberger, "Cream: biography", Allmusic, retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ S. Schinder and A. Schwartz, Icons of Rock: An Encyclopedia of the Legends Who Changed Music Forever (Greenwood, 2008), p. 218.

- ^ J. Ankeny, "Free: biography", Allmusic, retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ W. Ruhlmann, "Ten Years After: biography", Allmusic, retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ Barry Miles, The British Invasion: The Music, the Times, the Era (London: Sterling, 2009), ISBN 1402769768, p. 286.

- ^ S. Borthwick and Ron Moy, Popular Music Genres: an Introduction (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-7486-1745-0, p. 64.

- ^ C. Smith, 101 Albums that Changed Popular Music (Madison NY: Greenwood, 2009), ISBN 0-19-537371-5, pp. 64-5.

- ^ S. T. Erlewine, "Led Zeppelin: biography", Allmusic, retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ P. Buckley, The Rough Guide to Rock (London: Rough Guides, 3rd edn., 2003), ISBN 1-84353-105-4, p. 278.

- ^ E. Rivadavia, "Review: Deep Purple, In Rock", Allmusic, retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ M. Campbell and J. Brody, Rock and Roll: an Introduction (Cengage Learning, 2nd edn., 2008), ISBN 0-534-64295-0, pp. 213-4.

- ^ R. F. Schwartz, How Britain Got the Blues: the Transmission and Reception of American Blues Style in the United Kingdom (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), p. 242.

- ^ a b c Year of the Blues Archived 2012-12-15 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ^ Akbar, Arifa (2009-01-21). "Seasick Steve sings the blues for a Brit". The Independent. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ^ R. Brunning, The Fleetwood Mac Story: Rumours and Lies (Omnibus Press, 2004), p. 161.

- ^ "Mick Fleetwood Blues Band", Blues Matters, retrieved 20/06/09.

- ^ "Chris Rea: Confessions of a blues survivor", Independent, 26/03/04, retrieved 20/03/09.

- ^ R. Weissman, Blues: the Basics (Routledge, 2005), p. 69.

- ^ "Matt Schofield" and "When blues turns to gold" in Guitarist, 317 (July 2009), pp. 57-60 and 69-71.

- ^ "Blueberry Pie". MusicBrainz. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ Hodgett, Trevor. "Joe Bonamassa Interview". Blues in Britain. Clikka. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ a b W. Kaufman and H. S. Macpherson, Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History (ABC-CLIO, 2005), p. 154.

References

[edit]- Bane, Michael (1982) White Boy Singin' the Blues, London: Penguin, 1982, ISBN 0-14-006045-6.

- Bob Brunning, Blues: The British Connection, Helter Skelter Publishing, London 2002, ISBN 1-900924-41-2 – First edition 1986 – Second edition 1995 Blues in Britain

- Bob Brunning, The Fleetwood Mac Story: Rumours and Lies, Omnibus Press London, 1990 and 1998, ISBN 0-7119-6907-8

- Martin Celmins, Peter Green – Founder of Fleetwood Mac, Sanctuary London, 1995, foreword by B. B. King, ISBN 1-86074-233-5

- Fancourt, Leslie, (1989) British blues on record (1957–1970), Retrack Books.

- Gilliland, John (1969). "String Man" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- Dick Heckstall-Smith, The safest place in the world: A personal history of British Rhythm and blues, 1989 Quartet Books Limited, ISBN 0-7043-2696-5 – Second Edition : Blowing The Blues – Fifty Years Playing The British Blues, 2004, Clear Books, ISBN 1-904555-04-7

- Christopher Hjort, Strange brew: Eric Clapton and the British blues boom, 1965-1970, foreword by John Mayall, Jawbone 2007, ISBN 1-906002-00-2

- Dinu Logoz, John Mayall: The Blues Crusader - His Life, His Music, His bands, Edition Olms Zürich, 2015, ISBN 978-3-283-01228-1

- John Mayall with Joel McIver, Blues From Laurel Canyon: My Life as a Bluesman, foreword by Mick Fleetwood, Omnibus Press London, 2019, ISBN 978-17855-817-86

- Sumer McStravick and John Roos, Blues-Rock Explosion, foreword by Bob Brunning, Old Goat Publishing, Mission Viejo, California, 2001, ISBN 0-9701332-7-8

- Paul Myers, Long John Baldry and the Birth of the British Blues, Vancouver 2007, GreyStone Books, ISBN 1-55365-200-2

- Harry Shapiro Alexis Korner: The Biography, Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, London 1997, Discography by Mark Troster, ISBN 0-7475-3163-3

- Schwartz, Roberta Freund, (2007) How Britain got the blues : The transmission and reception of American blues style in the United Kingdom Ashgate, ISBN 0-7546-5580-6.

- Mike Vernon, The Blue Horizon story 1965-1970 vol.1, notes of the booklet of the Box Set (60 pages)