Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

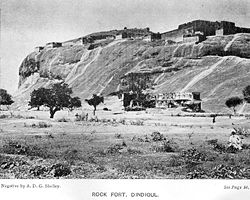

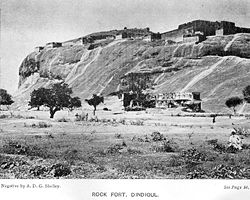

Dindigul Fort

View on Wikipedia

The Dindigul Fort or Dindigul Malai Kottai and Abirami amman Kalaheswarar Temple was built in 16th-century by Madurai Nayakar Dynasty situated in the town of Dindigul in the state of Tamil Nadu in India. The fort was built by the Madurai Nayakar king Muthu Krishnappa Nayakar in 1605. In the 18th century the fort passed on to Kingdom of Mysore (Mysore Wodeyars). Later it was occupied by Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan the fort was of strategic importance. In 1799, it went to the control of the British East India Company during the Polygar Wars. There is an abandoned temple on its peak apart from few cannons sealed with balls inside. These cannons are very heavy. In modern times, the fort is maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India and is open to tourists.

Key Information

Etymology

[edit]Dindigul city derives its name from a portmanteau of Thindu a Tamil word which means a ledge or a headrest attached to ground and kal another Tamil word which means Rock. Appar, the Saiva poet visited the city and noted it in his works in Tevaram. Dindigul finds mention in the book Padmagiri Nadhar Thenral Vidu thudhu written by the poet Palupatai sokkanathar as Padmagiri. This was later stated by U. V. Swaminatha Iyer (1855–1942) in his foreword to the above book. He also mentions that Dindigul was originally called Dindeecharam.[1]

History

[edit]

Early Dindigul history

[edit]The history of Dindigul is centered on the fort over the small rock hill and fort. Dindigul region was the border of the three prominent kingdoms of South India, the Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas. During the first century A.D., the Chola king Karikal Cholan captured the Pandya kingdom and Dindigul came under the Chola rule. During the sixth century, the Pallavas took over most provinces of Southern India and Dindigul was under the rule of Pallavas until Cholas regained the state in the 9th century and the Pandyas regained control by the 13th century.

In the 14th century, half of Tamil Nadu kingdoms were under the short-reigned Delhi Sultanates with Madurai Sultanate ruling this region between 1335–1378. By end of 1378, the Muslim rulers were defeated by the Vijayanagara army who later established their rule.

Madurai Nayaks

[edit]

In 1559 Madurai Nayaks, till then part of Vijayanagara Empire became powerful and with Dindigul became a strategic gateway to their kingdom from North . After the death of King Viswanatha Nayak in 1563, Muthukrisna Nayakka became the king of kingdom in 1602 A.D who built the strong hill fort in 1605 A.D. He also built a fort at the bottom of the hill. Muthuveerappa Nayak and Thirumalai Nayak followed Muthukrishna Nayak. Dindigul came to prominence once again during Nayaks rule of Madurai under Thirumalai Nayak. After his immediate unsuccessful successors, Rani Mangammal became the ruler of the region who ruled efficiently.[1]

Under Mysore Rayas and Hyder Ali

[edit]In 1742, the Mysore army under the leadership of Venkata Raya conquered Dindigul. He governed Dindigul as a representative of Maharaja of Mysore. There were Eighteen Palayams (a small region consists of few villages) during his reign and all these palayams were under Dindigul Semai with Dindiguls capital. These palayams wanted to be independent and refused to pay taxes to venkatarayer.[1][2] In 1748, Venkatappa was made governor of the region in place of Venkatarayer, who also failed. In 1755, Mysore Maharaja sent Haider Ali to Dindigul to handle the situation. Later Haider Ali became the de facto ruler of Mysore and in 1777, he appointed Purshana Mirsaheb as governor of Dindigul. He strengthened the fort. His wife Ameer-um-Nisha-Begam died during her delivery and her tomb is now called Begambur. In 1783 British army, led by captain long invaded Dindigul. In 1784, after an agreement between the Mysore Kingdom and British army, Dindigul was restored by Mysore Kingdom. In 1788, Tipu Sultan, the Son of Haider Ali, was crowned as King of Dindigul.[1][3][4][5]

Under British

[edit]In 1790, James Stewart of the British army gained control over Dindigul by invading it in the second war of Mysore. In a pact made in 1792, Tipu ceded Dindigul along with the fort to the English. Dindigul is the first region to come under English rule in the Madurai District. In 1798, the British army strengthened the hill fort with cannons and built sentinel rooms in every corner. The British army, under statten stayed at Dindigul fort from 1798 to 1859. After that Madurai was made headquarters of the British army and Dindigul was attached to it as a taluk. Dindigul was under the rule of the British Until India got our Independence on 15 August 1947.[1][3]

The fort played a major role during the Polygar wars, between the Palayakarars, Tipu Sultan duo aided by the French against the British, during the last decades of the 18th century. The polygar of Virupachi, Gopal Nayak commanded the Dindugal division of Polygars, and during the wars aided the Sivaganga queen Queen Velu Nachiyar and her commanders Maruthu Pandiyar Brothers to stay the fort after permission from Hyder Ali.[6]

Architecture

[edit]The rock fort is 900 ft (270 m) tall and has a circumference of 2.75 km (1.71 mi). Cannon and gunfire artillery were included in the fort during the 17th century. The fort was cemented with double walls to withstand heavy artillery. Cannons were installed at vantage points around the fort with an arms and ammunition godown built with safety measures. The double-walled rooms were fully protected against external threat and were well ventilated by round ventilation holes in the roof. A thin brick wall in one corner of the godown helped soldiers escape in case of emergency. The sloping ceiling of the godown prevented seepage of rainwater. The fort has 48 rooms that were once used as cells to lodge war prisoners and slaves, a spacious kitchen, a horse stable and a meeting hall for the army commanders. The fort also has its own rainwater reservoirs constructed by taking advantage of the steep gradient. The construction highlights the ingenuity of Indian kings in their military architecture.[7][8]

Maintenance

[edit]The fort is maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India and maintains it as a protected monument. An entry fee of ₹25 is charged for Indian citizens and ₹300 for foreigners. The fort receives few visitors in college and school students and the occasional foreign tourists. Visitors are allowed to walk around the tunnels and trenches that reveals the safety features of the structure. The temple has some sculptures and carvings, with untarnished rock cuts.

Visitors can view the ruins within the fort walls, arsenal depots, or animal stables) and damaged halls decorated with carved stone columns. Visitors are allowed to go up to the cannon point and look through the spy holes. The top of the fort also offers a scenic view of Dindigul on the eastern side and villages and farmland on the other sides. Lack of funds and facilities has kept the fort misused by nearby dwellers. But in 2005, Keeranur-based ASI in Pudukkottai district fenced the entire surroundings and refurbished some of the dilapidated structures.[7][9][10]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Historical moments". Dindigul municipality. 2011. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Nelson 1989, p. 258

- ^ a b Nelson 1989, pp. 286-93

- ^ Hasan, Mohibbul (2005). History of Tipu Sultan. Aakar Books. pp. 68–69. ISBN 81-87879-57-2.

- ^ Beveridge, Henry (1867). A comprehensive history of India, civil, military and social, from the first landing of the English, to the suppression of the Sepoy revolt:including an outline of the early history of Hindoostan, Volume 2. Blackie and son. pp. 222–24.

- ^ "Gopal Naicker Memorial ready for inauguration". The Hindu. Palani. 22 June 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ a b Basu, Soma (2 April 2005). "Pillow Rock". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 June 2006. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "Cannonballs unearthed from Dindigul fort". The Hindu. 2 March 2004. Archived from the original on 24 June 2004. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "Alphabetical List of Monuments - Tamil Nadu". Archaeological Survey of India. 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "List of ticketed monuments - Tamil Nadu". Archaeological Survey of India. 2011. Archived from the original on 18 August 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

References

[edit]- Nelson, James Henry (1989). The Madura Country: A Manual. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120604247.

External links

[edit]Dindigul Fort

View on GrokipediaOverview

Etymology

The name Dindigul derives from the Tamil words thindu (meaning pillow or ledge) and kal (meaning rock or stone), a portmanteau that alludes to the distinctive rocky hill resembling a pillow or resting ledge, which dominates the landscape and serves as the fort's foundation.[4] In historical Tamil literature, the site is referenced as Padmagiri in the poetic work Padmagiri Nadhar Thenral Vidu Thudhu by the 17th-century poet Palupatai Sokkanathar, a name evoking the "lotus mountain" and highlighting the hill's sacred or natural prominence.[5] This nomenclature was later corroborated by the renowned Tamil scholar U. V. Swaminatha Iyer in his compilations of ancient texts. Ancient inscriptions further indicate that the region bore names like Thindeeswaram or Dindeeswaram as early as the 7th–8th centuries CE, evolving into variants such as Dindeecharam in medieval records, reflecting its enduring association with the rocky terrain and temple sites.[6] Locally, the fort is commonly known as Dindigul Malai Kottai, where malai translates to hill and kottai to fort in Tamil, underscoring its elevated position on the natural rock outcrop.[1] This evolution of nomenclature from poetic and inscriptional forms to the modern Tamil descriptor emphasizes the fort's integral link to the geography of the bare, pillow-like hill.Location and Geography

Dindigul Fort is situated on a prominent 900-foot (270 m) granite hillock in the heart of Dindigul city, Tamil Nadu, India.[7] The site's precise coordinates are 10.36109°N 77.96167°E, placing it within a region known for its undulating terrain and historical significance.[8] This elevated position not only dominates the surrounding urban landscape but also underscores the fort's role as a key landmark in southern India. The hillock rises abruptly from the surrounding plains, forming a natural prominence. At its base, the hill features a circumference of approximately 2.75 km, emphasizing its compact yet imposing footprint amid the flat expanses typical of the area's geography.[7] This abrupt elevation contributes to the site's isolation and defensibility, with the granite composition providing a sturdy foundation resistant to erosion.%2037%20Rajendran%20166-168.pdf) The fort's location offers inherent natural defenses through its steep slopes and rugged rocky terrain, which historically deterred invaders by creating challenging access points.[9] Furthermore, its strategic positioning along ancient trade routes connecting Madurai to the north and Tiruchirappalli (Trichy) enhanced its importance as a vantage point for monitoring movement across the region.[10][11] The area's rainfall patterns, characterized by seasonal monsoons and occasional erratic distributions, played a crucial role in supporting ancient water management systems integrated into the site's design. These environmental factors ensured reliable water collection during wet periods, vital for sustaining the hillock's isolation in a semi-arid landscape.[10]History

Pre-Nayak Period

The region encompassing Dindigul Fort, situated on the strategic rock hill known as Malaikottai, fell under Chola rule in the 1st century AD following the conquest of the Pandya kingdom by King Karikala Chola. This marked the beginning of a period of contested control, as the area served as a vital border outpost for southern Indian kingdoms. Archaeological indications of early human activity include rock-cut structures, reflecting the site's longstanding defensive and religious significance.[1][7] By the 6th century, the Pallavas extended their dominion over much of southern India, including Dindigul, maintaining influence until the Cholas reasserted control in the 9th century. The Pandyas subsequently regained the territory by the 13th century, fortifying the hill to safeguard their realm against invasions from neighboring powers such as the Cheras, Cholas, and Pallavas, which led to over 30 recorded conflicts in the area. Evidence of religious activity during these early periods includes rock-cut Jain beds carved into the hill's face, pointing to a transient Jain presence without associated Brahmi inscriptions.[1][7] The decline of Pandya power in the 14th century brought the region under the Madurai Sultanate, an extension of Delhi Sultanate influence, from 1335 to 1378. The Vijayanagara Empire then intervened, defeating the Muslim rulers by 1378 and establishing lasting control. In 1538, Vijayanagara emperor Achutha Devarayar defeated the Chera king and laid foundations for temples on the site, incorporating Pandyan-style architecture with intricate stone carvings dedicated to deities like Abiramiamman and Padmagirinathar. These developments, including initial rock-cut features and temple bases, preceded the more extensive constructions under later regional powers.[1][7]Madurai Nayak Rule

The Dindigul Fort was constructed in 1605 by Muthu Krishnappa Nayaka, ruler of the Madurai Nayak dynasty, as a strategic hill fort to serve as a border defense outpost between the regions of Coimbatore and Madurai.[12] Built on an isolated natural hill rising to 1,223 feet above sea level, the structure utilized burnt bricks and stones, measuring approximately 400 yards in length and 300 yards in width, with an additional fortification at the base known as the "Pettaiwall."[12] This construction marked a significant military initiative during Muthu Krishnappa's reign from 1601 to 1609, aimed at securing the kingdom's northern frontiers against potential incursions.[1] Under subsequent Madurai Nayak rulers, the fort gained further prominence and underwent key enhancements. Thirumalai Nayak, who ruled from 1623 to 1659, reinforced and redressed the hill fort, solidifying its role as a vital defensive stronghold.[12] Later, during the regency of Rani Mangammal from 1689 to 1704, expansions included the addition of 600 steps leading to the hilltop, facilitating better access and logistical support for military operations.[12] These developments under Thirumalai Nayak and Rani Mangammal transformed the fort into a more robust installation, capable of storing arms and provisions essential for sustained defense.[1] The fort played a crucial strategic role in regional conflicts during the Madurai Nayak period, acting as a gateway to protect the kingdom from northern threats. In 1620, local palayakarars (feudal lords) under Nayak command, including those from Virupatchi and Kannivadi, successfully repelled an infiltration attempt by Mysorean forces led by Raja Udaiyar, demonstrating the fort's effectiveness in border skirmishes.[12] Its elevated position and fortified design provided a commanding vantage for surveillance and rapid response, underscoring its importance in maintaining the dynasty's territorial integrity amid ongoing rivalries.[1]Mysore Sultanate Period

The Dindigul Fort came under the control of the Mysore Kingdom in 1742, when the Mysore army, led by Venkata Raya, conquered the region from the Madurai Nayaks. This marked a significant transition in the fort's role, as it was integrated into Mysore's expanding territorial administration, with Venkata Raya governing Dindigul as a direct representative of the Mysore Maharaja. Building briefly on the existing Nayak defensive structures, the fort began to serve as a vital outpost for Mysore's southern frontier security.[1] In 1755, Haider Ali, then commander-in-chief of the Mysore forces, was dispatched to Dindigul by the Mysore Maharaja to address regional unrest. During his tenure, Haider Ali significantly fortified the site by constructing additional walls and equipping it with armaments, enhancing its defensive capabilities against potential threats from local chieftains and rival powers. These improvements transformed the fort into a more robust military stronghold, reflecting Haider Ali's broader strategy of consolidating Mysore's influence in Tamil Nadu. By 1777, as the de facto ruler of Mysore, he appointed governors such as Purshana Mirsaheb to oversee further reinforcements.[1] Tipu Sultan, Haider Ali's son, assumed direct rule over Dindigul in 1788, when he was crowned as its king. For the next four years, until 1792, the fort functioned as a strategic base for Tipu's southern military campaigns, including efforts to support allied local rulers and counter British advances in the region. Its elevated position allowed it to monitor trade routes and valleys, making it an essential surveillance point amid Mysore's ongoing conflicts, such as the Anglo-Mysore Wars. Tipu's administration emphasized the fort's tactical value, utilizing it to coordinate defenses and logistics during this turbulent period.[1] Following Tipu Sultan's defeat in the Third Anglo-Mysore War, the Treaty of Seringapatam in 1792 compelled him to cede Dindigul, along with the fort, to the British East India Company. This transfer ended Mysore's control over the site, which had been pivotal in over a dozen major engagements involving Mysore forces, underscoring the fort's enduring role in regional power struggles. The cession positioned Dindigul as the first area in the Madurai district to fall under British influence.[1]British Colonial Period

The British East India Company captured Dindigul Fort in 1790 during the Third Anglo-Mysore War under the command of James Stewart, following temporary captures in 1767 and 1783 during earlier Anglo-Mysore Wars. This seizure marked a pivotal shift in regional control, as the fort's strategic position on the passes into Madurai from the north made it essential for securing British interests in southern India. The acquisition was formalized in 1792 through the Treaty of Seringapatam, in which Tipu Sultan ceded Dindigul and the fort to the British East India Company following his defeat. From this point until India's independence in 1947, the fort functioned primarily as a military outpost, bolstering British administrative and defensive operations in the Madras Presidency.[1][13][2] To fortify its defenses, the British made significant modifications starting in 1798, including the installation of cannons along the ramparts and the construction of sentinel rooms at key corners for surveillance and troop positioning. These enhancements transformed the hill fort into a more robust garrison, capable of withstanding potential uprisings. British troops, led by an officer named Statten, occupied the site continuously from 1798 to 1859, using it as a base for regional patrols and logistics; afterward, Madurai was designated as the main military headquarters, though the fort retained its outpost role.[1] Dindigul Fort was central to the Polygar Wars (1799–1805), a series of rebellions where local chieftains, or Polygars (Palayakkarars), mounted fierce resistance against British revenue policies and territorial encroachments, often using the fort as a rallying point and supply hub. Alliances formed here, including support from Tipu Sultan and French advisors, enabled Polygars like Gopal Nayak of Virupachi to coordinate attacks, though British forces ultimately suppressed the uprisings through sieges and diplomacy. Earlier tensions in 1788 saw local leaders hide temple deities within the fort's confines to safeguard them from advancing British troops during conflicts near Coimbatore, underscoring its role as a sanctuary amid escalating hostilities. Additionally, in the late 18th century, rebel leader Umaithurai sought refuge and organizational support at the fort to challenge British authority, while Queen Velu Nachiyar had previously met Hyder Ali there in 1772 to strategize the recapture of Sivaganga, an alliance that echoed in later Polygar resistances.[1]Post-Independence Era

Following India's attainment of independence on August 15, 1947, Dindigul Fort seamlessly integrated into the sovereign nation, marking the end of British colonial oversight in the region.[1] The site, which had served as a strategic outpost during the colonial era, transitioned under Indian administrative control without significant disruptions, preserving its historical structures from the preceding period.[1] In the post-independence years, the fort was recognized as a centrally protected monument by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), aligning with the provisions of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act of 1958. This designation ensured systematic oversight and conservation efforts to safeguard the fort's integrity as a heritage asset.[14] Minor restoration works were undertaken throughout the 20th century to address weathering and structural wear, focusing on stabilizing the rock fortifications and pathways. To combat urban encroachments threatening the site's boundaries, protective fencing was installed around the fort in 2005, enhancing security and delineating the protected area from surrounding developments.[7] In the 21st century, the fort has solidified its role in fostering local identity in Dindigul, symbolizing the area's enduring spirit of resistance against historical oppressors. Occasional cultural events and commemorations, such as heritage walks and educational programs, continue to highlight its legacy of rebellions, drawing community participation and reinforcing its significance in regional narratives.[7]Architecture and Features

Structural Design

The Dindigul Fort is strategically positioned atop a prominent granite hill, exemplifying classic hilltop defensive architecture designed to leverage elevation for surveillance and protection. The rock formation rises approximately 280 feet (85 meters) above the surrounding terrain, with a base circumference of 2.75 kilometers, providing a natural barrier that integrates seamlessly with the surrounding rocky terrain.[15] Constructed primarily from local granite, the fort's layout emphasizes layered fortifications, including double walls that encircle the summit to absorb artillery impacts and deter sieges. This engineering approach allowed for multi-tiered defense, where the outer wall shielded the inner core while utilizing the hill's contours for added stability and concealment.[16] The structural design incorporates steep access paths, consisting of around 350 rock-cut steps, which served as a formidable deterrent to invaders by channeling attackers into narrow, easily defended chokepoints. These paths, carved directly into the natural rock face, blend human engineering with the site's geology, minimizing material needs while maximizing defensive utility through elevation changes and limited entry routes. The overall layout reflects adaptations to the undulating terrain, with bastions positioned at key vantage points to mount cannons and overlook approach paths.[15][17] Rooted in Madurai Nayak military traditions, the fort's architecture fuses robust granite construction with strategic spatial planning typical of 17th-century South Indian fortifications. Later modifications under Mysore Sultanate rule introduced Islamic architectural elements, such as reinforced bastions and utilitarian room additions, enhancing the original design for gunpowder-era warfare. British colonial enhancements further fortified select sections, though the core Nayak framework remains dominant.[16][18]Key Components and Artifacts

At the summit of Dindigul Fort stands the Kalahastheeswarar Temple, also known as the Abirami Amman Kalaheswarar Temple, constructed in 1538 by Achutha Devarayar of the Vijayanagara Empire, featuring Pandyan-style architecture with intricate stone carvings and empty niches that highlight its historical craftsmanship.[7] The temple's central shrine exemplifies delicate soapstone-influenced artistry, though its deities were removed and concealed in the town below during a British threat in 1788 to protect them from desecration.[7] The fort complex includes 48 rooms, originally used as prison cells for slaves and prisoners of war, along with stables for horses, storehouses, and other utilitarian spaces that supported prolonged sieges and daily operations.[18] These chambers, often well-ventilated with strategic air inlets, served multiple functions, including as barracks and secure storage areas integrated into the hill's rocky terrain.[18] Water management features prominently with two ancient rainwater reservoirs and storage tanks hewn into the rock, ensuring self-sufficiency during conflicts by capturing and conserving monsoon runoff for the garrison's needs.[7] Defensive elements include cannon mounts positioned at key vantage points, where artillery was installed by Hyder Ali with French technical aid in the late 18th century, alongside British-era armaments added in 1798 to bolster fortifications against local rebellions.[7][1] Pre-Nayak remnants are evident in rock-cut Jain beds sculpted into the hill's face, reflecting the region's early Jain influence from the 6th to 8th centuries CE, though lacking associated Brahmi inscriptions.[7] These elements, along with other carved features, underscore the site's layered occupation history. The fort's elevated position provides scenic viewpoints offering expansive panoramas of the surrounding Dindigul plains, enhancing its observational role in defense.[7]Significance and Legacy

Strategic and Cultural Importance

Dindigul Fort's strategic position on the northern frontier of the Pandya kingdom made it a critical outpost for defending Madurai against invasions from the Cheras, Cholas, and Pallavas, leveraging its approximately 280-foot (85 m) granite hill for surveillance and defense. Over two millennia, from the 2nd century AD, the site has been the scene of more than 30 wars involving multiple empires, including Pandya-Chera conflicts, Vijayanagara interventions in 1336 and 1538, and later struggles under various rulers.[7] Its elevated terrain and layered fortifications, such as double walls and sentry posts added by the Nayaks and British, enhanced its defensibility in these prolonged regional power dynamics.[7] The fort emerged as a potent symbol of resistance during the Polygar Wars in the late 18th century, where local Palayakkarars, including allies of Queen Velu Nachiyar and the Maruthu Pandiyar brothers, used it as a base against British expansion.[1] Similarly, in the Mysore-British conflicts from 1745 to 1792, it served as a key stronghold under Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, who fortified it with cannons before its final cession to the British in 1799.[7] These roles underscored its enduring function as a linchpin in South Indian military contests, transitioning from ancient border defense to colonial-era defiance.[1] Culturally, the fort stands as a marker of Tamil military architecture, embodying Pandyan stylistic influences through its rock-cut elements and temple integrations, such as the Abiramiamman and Padmagirinathar shrines with intricate carvings. In 2024, archaeologists discovered megalithic rock cupules dating back 4,000 years near the fort, further evidencing its prehistoric ritual use.[19] Evidence of early Jain presence, including inscribed beds, highlights the Pandyan era's religious pluralism and architectural adaptations.[7] By anchoring Dindigul's identity as a historical hub amid diverse imperial influences—from Chola-Pandya rivalries to British rule—the fort shapes local cultural narratives and reinforces regional heritage ties, including proximity to pilgrimage centers like the Palani Murugan Temple approximately 60 kilometers away.[1]Legends and Folklore

Local folklore portrays the hill on which Dindigul Fort stands, known as Padmagiri or Lotus Hill, as a sacred site revered since ancient times. According to temple traditions, Lord Brahma performed penance to Lord Shiva at this location to atone for his arrogance, and Shiva appeared to him from a divine lotus blooming on the hill, bestowing the name Padmagiriswarar upon the deity. This origin story echoes early Shaivite worship narratives from the Pandya era, where the hill's natural formation and the adjacent Kalahastheeswarar Temple—reflecting Pandyan architectural influences with intricate stone carvings—symbolized divine manifestation and spiritual potency.[20][7] A prominent legend centers on Queen Velu Nachiyar, the ruler of Sivaganga, who in 1772 disguised herself as a man to enter the fort's durbar hall and meet Hyder Ali, the Sultan of Mysore, seeking military aid against British forces. This clandestine encounter, where she impressed him with her resolve and strategic acumen conveyed in Urdu, forged a pivotal alliance that enabled her eventual reclamation of her kingdom in 1780, embodying tales of female empowerment and defiance in regional oral traditions.[7][21] Another enduring story from 1788 recounts the safeguarding of the fort's Abirami Amman and Padmagirinathar Temple deities amid fears of British looting during regional uprisings. Devotees purportedly removed the idols from their niches and concealed them in Dindigul town to protect them from desecration, a precaution that explains the temple's empty sanctums today and later inspired the construction of a new shrine in the town to house the returned icons, underscoring themes of piety and resistance in local lore.[7]Preservation and Access

Maintenance and Restoration

Following India's independence, the Dindigul Fort came under the management of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), which declared it a protected monument of national importance to safeguard its historical and architectural value.[14] This legal status, established in the early post-independence period, ensures systematic conservation efforts under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act of 1958.[22] As of 2024, residents have noted the site's generally good upkeep under ASI oversight.[7] Challenges to preservation include urban encroachment near the fort's periphery, prompting judicial interventions, such as the Madras High Court's May 2025 interim order restraining authorities from constructing an ornamental gateway near the Rockfort amid a petition concerning encroachments.[23] Funding for these initiatives primarily comes from the ASI's annual conservation budget, supplemented by contributions from local heritage organizations like the Inheritage Foundation, which supports documentation, volunteer-driven cleanups, and targeted restoration activities at the site.[24]Tourism and Visitor Experience

Dindigul Fort is open daily from 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM, with the last entry typically around 4:00 PM, allowing visitors ample time to explore the site without any holidays throughout the year.[25] Entry requires a nominal fee of ₹25 for Indian citizens and ₹300 for foreign nationals, reflecting standard Archaeological Survey of India pricing for protected monuments.[26] These timings and fees make the fort accessible for day trips, particularly for those combining it with nearby heritage sites in Tamil Nadu. Access to the fort involves ascending approximately 350 carved stone steps, a moderate climb suitable for history enthusiasts and casual trekkers, though it may challenge those with mobility issues.[15] The ascent rewards visitors with panoramic views of Dindigul town, surrounding green fields, and distant hills, especially striking at sunrise or sunset when the landscape glows in soft light.[15] Ongoing maintenance by the Archaeological Survey of India ensures the steps and pathways remain safe for public use.[27] Guided tours are available on-site, led by knowledgeable locals who highlight key features such as the ancient cannons positioned along the fortifications and the hilltop temple dedicated to Lord Shiva, providing context on the fort's defensive role and spiritual significance.[28] The site attracted 36,071 resident visitors in 2023, primarily domestic tourists, and is actively promoted by Tamil Nadu Tourism as part of regional heritage circuits that connect historical forts and cultural landmarks across the state.[29][15] This integration enhances its appeal for educational and leisure travel, fostering appreciation of Tamil Nadu's architectural legacy.References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Dindigul