Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

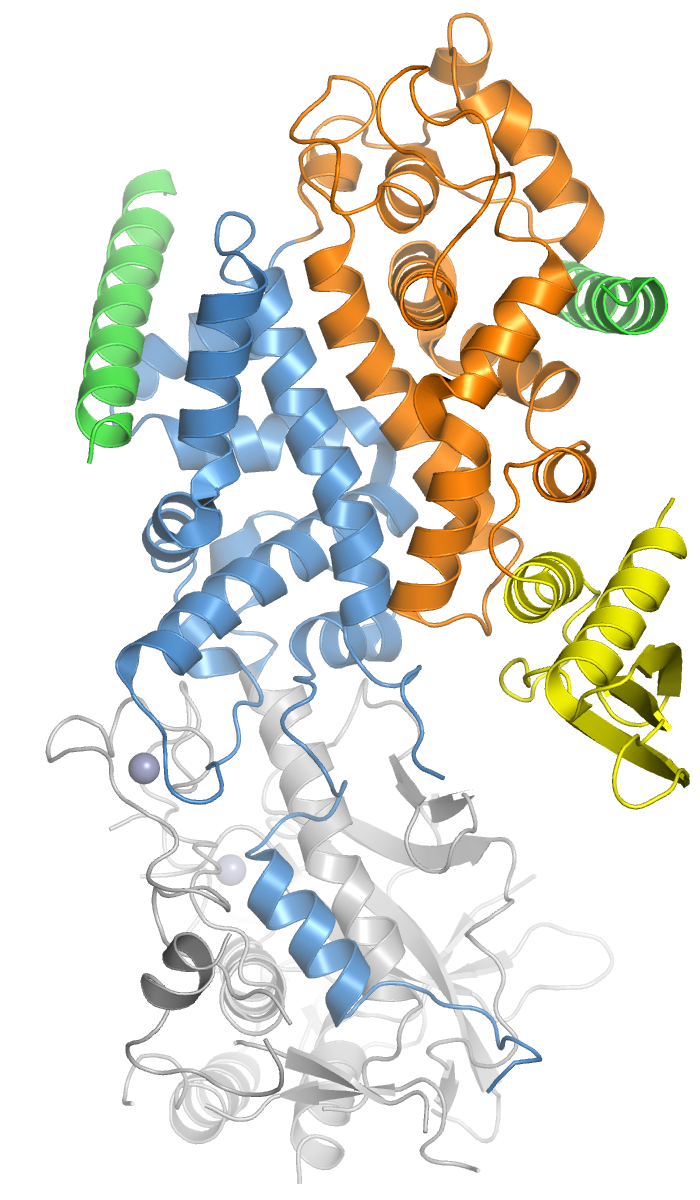

Drosha

View on Wikipedia

Drosha is a Class 2 ribonuclease III enzyme[5] that in humans is encoded by the DROSHA (formerly RNASEN) gene.[6][7][8] It is the primary nuclease that executes the initiation step of miRNA processing in the nucleus. It works closely with DGCR8 and in correlation with Dicer. It has been found significant in clinical knowledge for cancer prognosis.[9] and HIV-1 replication.[10]

History

[edit]Human Drosha was cloned in 2000 when it was identified as a nuclear dsRNA ribonuclease involved in the processing of ribosomal RNA precursors.[11] The other two human enzymes that participate in the processing and activity of miRNA are the Dicer and Argonaute proteins. Recently, Drosha has been associated with cancer [9] and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia prognosis,[12] and HIV-1 replication.[10]

Function

[edit]Members of the ribonuclease III superfamily of double-stranded (ds) RNA-specific endoribonucleases participate in diverse RNA maturation and decay pathways in eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells.[13] The RNase III Drosha is the core nuclease that executes the initiation step of microRNA (miRNA) processing in the nucleus.[8][11]

The microRNAs thus generated are short RNA molecules that regulate a wide variety of other genes by interacting with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to induce cleavage of complementary messenger RNA (mRNA) as part of the RNA interference pathway. MicroRNA molecules are synthesized as long RNA primary transcripts known as a pri-miRNAs, which are cleaved by Drosha to produce a characteristic stem-loop structure of about 70 base pairs long, known as a pre-miRNA.[11] Pre-miRNAs, when associated with EXP5, are stabilized due to removal of the 5' cap and 3' poly(A) tail.[14] Drosha exists as part of a protein complex called the Microprocessor complex, which also contains the double-stranded RNA binding protein DGCR8 (called Pasha in D. melanogaster and C. elegans).[15] DGCR8 is essential for Drosha activity and is capable of binding single-stranded fragments of the pri-miRNA that are required for proper processing.[16] The Drosha complex also contains several auxiliary factors such as EWSR1, FUS, hnRNPs, p68, and p72.[17]

Both Drosha and DGCR8 are localized to the cell nucleus, where processing of pri-miRNA to pre-miRNA occurs. These two proteins homeostatically control miRNA biogenesis by an auto-feedback loop.[17] A 2nt 3' overhang is generated by Drosha in the nucleus recognized by Dicer in the cytoplasm, which couples the upstream and downstream processing events. Pre-miRNA is then further processed by the RNase Dicer into mature miRNAs in the cell cytoplasm.[11][17] There also exists an isoform of Drosha that does not contain a nuclear localization signal, which results in the generation of c-Drosha.[18][19] This variant has been shown to localize to the cell cytoplasm rather than the nucleus, but the effects on pri-miRNA processing are yet unclear.

Both Drosha and Dicer also participate in the DNA damage response.[20]

Certain miRNAs have been found to deviate from conventional biogenesis pathways and do not necessarily require Drosha or Dicer, which is because they do not require the processing of pri-miRNA to pre-miRNA.[17] Drosha-independent miRNAs derive from mirtrons, which are genes that encode for miRNAs in their introns and make use of splicing to bypass Drosha cleavage. Simtrons are mirtron-like, splicing-independent, and do require Drosha mediated cleavage, although they do not require most proteins in the canonical pathway such as DGCR8 or Dicer.[10]

Clinical significance

[edit]Drosha and other miRNA processing enzymes may be important in cancer prognosis.[9] Both Drosha and Dicer can function as master regulators of miRNA processing and have been observed to be down-regulated in some types of breast cancer.[21] The alternative splicing patterns of Drosha in The Cancer Genome Atlas have also indicated that c-drosha appears to be enriched in various types of breast cancer, colon cancer, and esophageal cancer.[19] However, the exact nature of the association between microRNA processing and tumorigenesis is unclear,[22] but its function can be effectively examined by siRNA knockdown based on an independent validation.[23]

Drosha and other miRNA processing enzymes may also be important in HIV-1 replication. miRNAs contribute to the innate antiviral defense. This can be shown by the knockdown of two important miRNA processing proteins, Drosha and Dicer, which leads to a significant enhancement of viral replication in PBMCs from HIV-1-infected patients. Thus, Drosha, in conjunction with Dicer, seem to have a role in controlling HIV-1 replication.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000113360 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022191 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Filippov V, Solovyev V, Filippova M, Gill SS (March 2000). "A novel type of RNase III family proteins in eukaryotes". Gene. 245 (1): 213–221. doi:10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00571-5. PMID 10713462.

- ^ Filippov V, Solovyev V, Filippova M, Gill SS (March 2000). "A novel type of RNase III family proteins in eukaryotes". Gene. 245 (1): 213–221. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00571-5. PMID 10713462.

- ^ Wu H, Xu H, Miraglia LJ, Crooke ST (November 2000). "Human RNase III is a 160-kDa protein involved in preribosomal RNA processing". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (47): 36957–36965. doi:10.1074/jbc.M005494200. PMID 10948199.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: RNASEN ribonuclease III, nuclear".

- ^ a b c Slack FJ, Weidhaas JB (December 2008). "MicroRNA in cancer prognosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (25): 2720–2722. doi:10.1056/NEJMe0808667. PMC 10035200. PMID 19092157.

- ^ a b c d Swaminathan G, Navas-Martín S, Martín-García J (March 2014). "MicroRNAs and HIV-1 infection: antiviral activities and beyond". Journal of Molecular Biology. 426 (6): 1178–97. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2013.12.017. PMID 24370931.

- ^ a b c d Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, et al. (September 2003). "The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing". Nature. 425 (6956): 415–419. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..415L. doi:10.1038/nature01957. PMID 14508493. S2CID 4421030.

- ^ Kyriakidis I, Pelagiadis I, Pontikoglou C, Papadaki HA, Stiakaki E (2025). "Association of DROSHA Variants with Susceptibility and Outcomes in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia". Curr Issues Mol Biol. 47 (6): 473. doi:10.3390/cimb47060473. PMC 12191901.

- ^ Fortin KR, Nicholson RH, Nicholson AW (August 2002). "Mouse ribonuclease III. cDNA structure, expression analysis, and chromosomal location". BMC Genomics. 3 (1) 26. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-3-26. PMC 122089. PMID 12191433.

- ^ Sloan KE, Gleizes PE, Bohnsack MT (May 2016). "Nucleocytoplasmic Transport of RNAs and RNA-Protein Complexes". Journal of Molecular Biology. 428 (10 Pt A): 2040–59. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.023. PMID 26434509.

- ^ Denli AM, Tops BB, Plasterk RH, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ (November 2004). "Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex". Nature. 432 (7014): 231–235. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..231D. doi:10.1038/nature03049. PMID 15531879. S2CID 4425505.

- ^ Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Nam JW, Heo I, Rhee JK, et al. (June 2006). "Molecular basis for the recognition of primary microRNAs by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex". Cell. 125 (5): 887–901. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.043. PMID 16751099. S2CID 453021.

- ^ a b c d Suzuki HI, Miyazono K (January 2011). "Emerging complexity of microRNA generation cascades". Journal of Biochemistry. 149 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1093/jb/mvq113. PMID 20876186.

- ^ Link S, Grund SE, Diederichs S (June 2016). "Alternative splicing affects the subcellular localization of Drosha". Nucleic Acids Research. 44 (11): 5330–5343. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw400. PMC 4914122. PMID 27185895.

- ^ a b Dai L, Chen K, Youngren B, Kulina J, Yang A, Guo Z, et al. (December 2016). "Cytoplasmic Drosha activity generated by alternative splicing". Nucleic Acids Research. 44 (21): 10454–10466. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw668. PMC 5137420. PMID 27471035.

- ^ Francia S, Michelini F, Saxena A, Tang D, de Hoon M, Anelli V, et al. (August 2012). "Site-specific DICER and DROSHA RNA products control the DNA-damage response". Nature. 488 (7410): 231–235. Bibcode:2012Natur.488..231F. doi:10.1038/nature11179. PMC 3442236. PMID 22722852.

- ^ Thomson JM, Newman M, Parker JS, Morin-Kensicki EM, Wright T, Hammond SM (August 2006). "Extensive post-transcriptional regulation of microRNAs and its implications for cancer". Genes & Development. 20 (16): 2202–2207. doi:10.1101/gad.1444406. PMC 1553203. PMID 16882971.

- ^ Iorio MV, Croce CM (June 2012). "microRNA involvement in human cancer". Carcinogenesis. 33 (6): 1126–1133. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgs140. PMC 3514864. PMID 22491715.

- ^ Munkácsy G, Sztupinszki Z, Herman P, Bán B, Pénzváltó Z, Szarvas N, et al. (September 2016). "Validation of RNAi Silencing Efficiency Using Gene Array Data shows 18.5% Failure Rate across 429 Independent Experiments". Molecular Therapy. Nucleic Acids. 5 (9) e366. doi:10.1038/mtna.2016.66. PMC 5056990. PMID 27673562.

Further reading

[edit]- Gunther M, Laithier M, Brison O (July 2000). "A set of proteins interacting with transcription factor Sp1 identified in a two-hybrid screening". Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 210 (1–2): 131–142. doi:10.1023/A:1007177623283. PMID 10976766. S2CID 1339642.

- Fortin KR, Nicholson RH, Nicholson AW (August 2002). "Mouse ribonuclease III. cDNA structure, expression analysis, and chromosomal location". BMC Genomics. 3 (1) 26. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-3-26. PMC 122089. PMID 12191433.

- Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, et al. (September 2003). "The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing". Nature. 425 (6956): 415–419. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..415L. doi:10.1038/nature01957. PMID 14508493. S2CID 4421030.

- Gregory RI, Yan KP, Amuthan G, Chendrimada T, Doratotaj B, Cooch N, et al. (November 2004). "The Microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs". Nature. 432 (7014): 235–240. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..235G. doi:10.1038/nature03120. PMID 15531877. S2CID 4389261.

- Zeng Y, Yi R, Cullen BR (January 2005). "Recognition and cleavage of primary microRNA precursors by the nuclear processing enzyme Drosha". The EMBO Journal. 24 (1): 138–148. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600491. PMC 544904. PMID 15565168.

- Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN (December 2004). "The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing". Genes & Development. 18 (24): 3016–3027. doi:10.1101/gad.1262504. PMC 535913. PMID 15574589.

- Landthaler M, Yalcin A, Tuschl T (December 2004). "The human DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 and Its D. melanogaster homolog are required for miRNA biogenesis". Current Biology. 14 (23): 2162–2167. Bibcode:2004CBio...14.2162L. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.001. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-EB83-3. PMID 15589161. S2CID 13266269.

- Zeng Y, Cullen BR (July 2005). "Efficient processing of primary microRNA hairpins by Drosha requires flanking nonstructured RNA sequences". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (30): 27595–27603. doi:10.1074/jbc.M504714200. PMID 15932881.

- Irvin-Wilson CV, Chaudhuri G (2006). "Alternative initiation and splicing in dicer gene expression in human breast cells". Breast Cancer Research. 7 (4) R563: R563 – R569. doi:10.1186/bcr1043. PMC 1175071. PMID 15987463.

- Kimura K, Wakamatsu A, Suzuki Y, Ota T, Nishikawa T, Yamashita R, et al. (January 2006). "Diversification of transcriptional modulation: large-scale identification and characterization of putative alternative promoters of human genes". Genome Research. 16 (1): 55–65. doi:10.1101/gr.4039406. PMC 1356129. PMID 16344560.

- Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, et al. (November 2006). "Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks". Cell. 127 (3): 635–648. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. PMID 17081983. S2CID 7827573.

- Sugito N, Ishiguro H, Kuwabara Y, Kimura M, Mitsui A, Kurehara H, et al. (December 2006). "RNASEN regulates cell proliferation and affects survival in esophageal cancer patients". Clinical Cancer Research. 12 (24): 7322–7328. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0515. PMID 17121874. S2CID 7569257.

- Kim YK, Kim VN (February 2007). "Processing of intronic microRNAs". The EMBO Journal. 26 (3): 775–783. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601512. PMC 1794378. PMID 17255951.

- Xing L, Kieff E (September 2007). "Epstein-Barr virus BHRF1 micro- and stable RNAs during latency III and after induction of replication". Journal of Virology. 81 (18): 9967–9975. doi:10.1128/JVI.02244-06. PMC 2045418. PMID 17626073.