Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sequential game

View on Wikipedia

In game theory, a sequential game is defined as a game where one player selects their action before others, and subsequent players are informed of that choice before making their own decisions.[1] This turn-based structure, governed by a time axis, distinguishes sequential games from simultaneous games, where players act without knowledge of others’ choices and outcomes are depicted in payoff matrices (e.g., rock-paper-scissors).

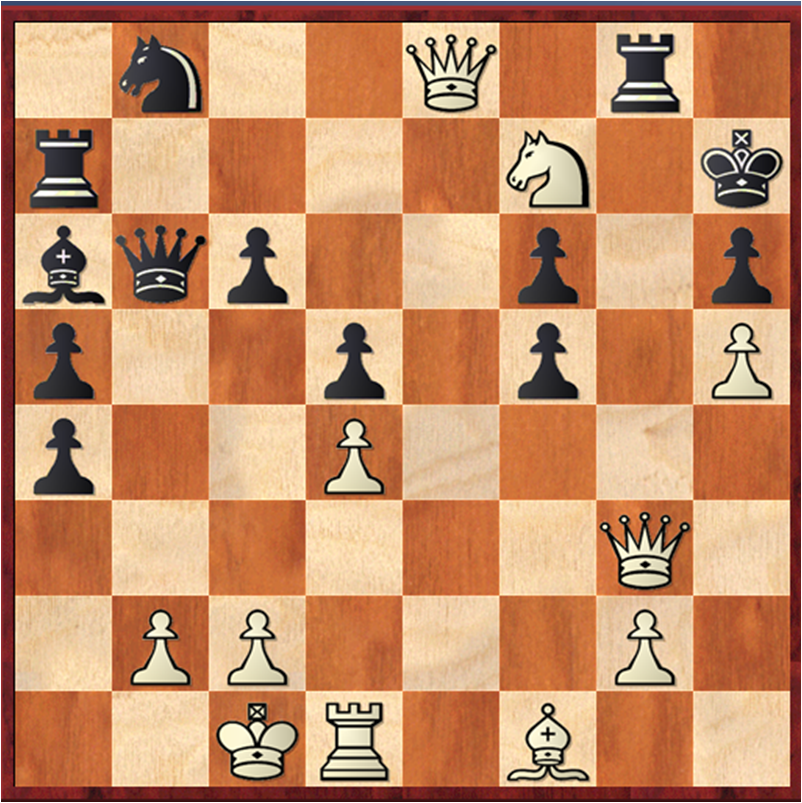

Sequential games are a type of dynamic game, a broader category where decisions occur over time (e.g., differential games), but they specifically emphasize a clear order of moves with known prior actions. Because later players know what earlier players did, the order of moves shapes strategy through information rather than timing alone. Sequential games are typically represented using decision trees, which map out all possible sequences of play, unlike the static matrices of simultaneous games. Examples include chess, infinite chess, backgammon, tic-tac-toe, and Go, with decision trees varying in complexity—from the compact tree of tic-tac-toe to the vast, unmappable tree of chess.[2]

Representation and analysis

[edit]Decision trees, the extensive form of sequential games, provide a detailed framework for understanding how a game unfolds.[3] They outline the order of players’ actions, the frequency of decisions, and the information available at each decision point, with payoffs assigned to terminal nodes. This representation was introduced by John von Neumann and refined by Harold W. Kuhn between 1910 and 1930.[3]

Sequential games with perfect information—where all prior moves are known—can be analyzed using combinatorial game theory, a mathematical approach to strategic decision-making. In such games, a subgame perfect equilibrium can be determined through backward induction, a process of working from the end of the game back to the start to identify optimal strategies.[4]

Games can also be categorized by their outcomes: a game is strictly determined if rational players arrive at one clear payoff using fixed, non-random strategies (known as "pure strategies"), or simply determined if the single rational payoff requires players to mix their choices randomly (using "mixed strategies").[5]

Types and dynamics

[edit]Sequential games encompass various forms, including repeated games, where players engage in a series of stage games, and each stage’s outcome shapes the next.[3] In repeated games, players have full knowledge of prior stages, and a discount rate (between 0 and 1) is often applied to assess long-term payoffs, reflecting the reduced value of future gains. This structure introduces psychological dimensions like trust and revenge, as players adjust their strategies based on past interactions. In contrast, simultaneous games lack this sequential progression, relying instead on concurrent moves and payoff matrices.

Many combinatorial games, such as chess or Go, align with the sequential model due to their turn-based nature. The complexity of these games varies widely: a simple game like tic-tac-toe has a manageable decision tree, while chess’s tree is so expansive that even modern computers cannot fully explore it.[6] These examples illustrate how sequential games blend strategic depth with temporal dynamics.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brocas; Carrillo; Sachdeva (2018). "The Path to Equilibrium in Sequential and Simultaneous Games". Journal of Economic Theory. 178: 246–274. doi:10.1016/j.jet.2018.09.011. S2CID 12989080.

- ^ Claude Shannon (1950). "Programming a Computer for Playing Chess" (PDF). Philosophical Magazine. 41 (314).

- ^ a b c Aumann, R. J. Game Theory.[full citation needed]

- ^ Aliprantis, Charalambos D. (August 1999). "On the backward induction method". Economics Letters. 64 (2): 125–131. doi:10.1016/s0165-1765(99)00068-3.

- ^ Aumann, R.J. (2008), Palgrave Macmillan (ed.), "Game Theory", The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 1–40, doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_942-2, ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5, retrieved 2021-12-08

- ^ Claude Shannon (1950). "Programming a Computer for Playing Chess" (PDF). Philosophical Magazine. 41 (314).

Sequential game

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A sequential game is a type of non-cooperative game in game theory in which players make decisions in a predefined order, with each player acting at their designated turn and subsequent players having the potential to observe prior actions. This structure contrasts with simultaneous-move games by emphasizing the timing and observability of choices, allowing for strategic interactions that unfold over multiple stages.[2] Key characteristics of sequential games include the strict ordering of moves, which enables early actors to commit to strategies that constrain or influence the options available to later players, and their resolution through the extensive form, a representational framework that captures the sequence, information, and contingencies of play. These features highlight how sequential games model real-world scenarios involving timing, such as negotiations or resource allocation, where the first-mover advantage can shape outcomes. The foundational concept of sequential games traces its origins to the work of John von Neumann in the 1920s and 1940s, who introduced the extensive form in his 1928 paper on parlor games and expanded it in the 1944 book Theory of Games and Economic Behavior co-authored with Oskar Morgenstern, providing a mathematical basis for analyzing ordered decision-making. The term and modern formalization gained prominence in the 1960s through contributions by Reinhard Selten, who refined equilibrium analysis for such games, building directly on von Neumann's framework to address dynamic strategic behavior. In sequential games, players receive payoffs only upon reaching a terminal outcome, determined by the entire path of moves traversed in the game tree, ensuring that strategies account for the cumulative effects of all decisions.[5]Distinction from Simultaneous Games

In simultaneous games, players make their decisions concurrently, without knowledge of the actions chosen by others, which is typically represented in normal form using payoff matrices.[2] A classic example is the Prisoner's Dilemma, where both players select cooperate or defect at the same time, leading to a unique Nash equilibrium of mutual defection as each player's best response to the anticipated choice of the other.[2] This structure emphasizes static best-response strategies and often results in multiple possible equilibria, some of which may rely on non-credible assumptions about off-path behavior.[6] Sequential games, by contrast, involve players acting in a defined order, with later movers able to observe prior actions, which introduces dynamic strategic foresight and timing into the interaction.[2] This observability enables credible threats or promises, as first movers can commit to actions that shape subsequent responses, potentially resolving ambiguities present in simultaneous settings and reducing the number of plausible equilibria.[7] A prominent illustration of this contrast appears in oligopoly models, such as the Stackelberg competition, where the leader firm sets output first and the follower responds, unlike the simultaneous quantity choices in the Cournot model.[8] In the Stackelberg setup, the leader produces more (e.g., 150 units versus the follower's 75 units in a duopoly with linear demand), resulting in higher total output, lower price, and greater leader profit compared to the symmetric Cournot equilibrium (100 units each).[8] This first-mover commitment alters the outcome by making the leader's strategy observable and binding, demonstrating how sequential timing can create advantages absent in concurrent decision-making.[8] The sequential structure facilitates more refined analysis through concepts like subgame perfection, which requires strategies to be optimal in every subgame, thereby eliminating non-credible threats that may persist in Nash equilibria of simultaneous games.[6] This refinement ensures sequential rationality throughout the game tree, providing a stricter criterion for equilibrium selection than the best-response focus of simultaneous models.[6]Representation

Extensive Form and Game Trees

The extensive form provides a complete and explicit representation of a sequential game, specifying the players involved, the order and sequences of their moves, the information available to each player at decision points, chance events if present, and the payoffs resulting from all possible outcomes.[9] Formally, an extensive form game consists of a finite set of players , a tree-structured set of nodes with a designated root and terminal nodes , a player assignment function indicating who moves at each non-terminal node (or chance if applicable), action sets for each non-terminal node , probability distributions over actions at chance nodes, and payoff functions for each player at terminal nodes.[10] This structure captures the temporal aspect of sequential decision-making, distinguishing it from normal form representations that abstract away the order of play.[9] Game trees visualize the extensive form as a directed acyclic graph rooted at the initial decision point, typically the first player's move in a two-player game. Each non-terminal node represents a decision point—either controlled by a specific player or by chance—while branches emanating from a node correspond to the available actions in , leading to successor nodes. Terminal nodes at the leaves of the tree are labeled with payoff vectors , reflecting the outcomes for all players. For instance, in a two-player sequential game, the root node is assigned to player 1, with branches for their actions branching to player 2's decision nodes or terminals, ensuring the tree exhaustively maps all possible move sequences.[10] Information sets partition the non-terminal nodes to indicate which positions a player cannot distinguish, though their full role in imperfect information is detailed separately.[9] Standard notation in game trees employs distinct symbols to clarify node types: player decision nodes are often marked with black dots or squares labeled by the acting player (e.g., "Player 1"), while chance nodes use open circles to denote probabilistic moves by nature. Branches are labeled with actions (e.g., "Up" or "Left"), and terminal payoffs are placed at leaves, sometimes with probabilities if chance events precede them. Strategies, which specify actions across relevant nodes, may be labeled on branches for clarity in pure strategy representations, though behavioral strategies are more common in mixed settings.[10] To manage complexity in large extensive form games, normalization techniques prune irrelevant subtrees—such as those unreachable due to prior moves or dominated actions—reducing the tree without altering strategic content. Additionally, the reduced normal form converts the extensive form into an equivalent normal form game by focusing on behavioral strategies at information sets, eliminating redundant pure strategy profiles and pruning the action space for computational efficiency.[11] These methods preserve the game's essential structure while facilitating analysis in practice.[12]Information Sets and Strategies

In sequential games with imperfect information, uncertainty is modeled using information sets, which are partitions of the nodes in the game tree where a player cannot distinguish between the nodes due to unobserved prior actions or chance moves. These sets group histories that appear identical to the player at the time of decision-making, such as when previous moves are hidden or simultaneous. A player's strategy in such games must account for this uncertainty by specifying actions contingent on the information set reached, rather than on specific nodes. A pure strategy is a complete, deterministic plan that assigns an action to every information set controlled by the player, effectively outlining behavior for all possible distinguishable situations. In contrast, a mixed strategy is a probability distribution over pure strategies, allowing randomization across these plans. For finite games with perfect recall—where players remember their past actions—behavioral strategies provide an equivalent representation, assigning probabilities directly to actions at each information set, which simplifies analysis without altering outcomes. This equivalence was established by Harold Kuhn, who showed that mixed and behavioral strategies yield the same expected payoffs under perfect recall. The strategy space in sequential games expands rapidly, as the number of pure strategies grows exponentially with the depth and branching factor of the game tree, particularly with increasing information sets. For instance, if a player has n information sets with k actions available at each, the total number of pure strategies is k^n; for binary choices (k=2), this is 2^n, which grows exponentially with the number of information sets, rendering full enumeration computationally infeasible for complex games and motivating approximations in practice.[13] A representative example occurs in poker-like games, where an information set encompasses all possible private card combinations consistent with the observed public actions and the player's hand, as the exact cards dealt to opponents remain hidden. In Texas Hold'em, for instance, a player's decision to bet or fold at a given betting round groups indistinguishable states based on incomplete knowledge of opponents' holdings, requiring strategies to specify actions across this set.[14]Solution Concepts

Backward Induction

Backward induction is a recursive procedure used to solve finite sequential games represented in extensive form with perfect information. It determines the optimal strategy profile by starting at the end of the game tree and working backwards to the initial node, assuming rational play by all players at every decision point. This method, first systematically applied in the analysis of extensive-form games by von Neumann and Morgenstern, ensures that strategies are sequentially rational throughout the game. The algorithm of backward induction operates as follows:- Begin at the terminal nodes of the game tree, where payoffs are fully specified for each player based on the path leading to that outcome.

- Move backward to the penultimate decision nodes: for each such node controlled by a player, select the action that maximizes that player's payoff, taking into account the payoffs at the terminal nodes reachable from those actions.

- Continue this process iteratively toward earlier decision nodes, at each step choosing the optimal action given the previously determined optimal continuations in subsequent subgames.