Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Normal-form game

View on WikipediaIn game theory, normal form is a description of a game. Unlike extensive form, normal-form representations are not graphical per se, but rather represent the game by way of a matrix. While this approach can be of greater use in identifying strictly dominated strategies and Nash equilibria, some information is lost as compared to extensive-form representations. The normal-form representation of a game includes all perceptible and conceivable strategies, and their corresponding payoffs, for each player.

In static games of complete, perfect information, a normal-form representation of a game is a specification of players' strategy spaces and payoff functions. A strategy space for a player is the set of all strategies available to that player, whereas a strategy is a complete plan of action for every stage of the game, regardless of whether that stage actually arises in play. A payoff function for a player is a mapping from the cross-product of players' strategy spaces to that player's set of payoffs (normally the set of real numbers, where the number represents a cardinal or ordinal utility—often cardinal in the normal-form representation) of a player, i.e. the payoff function of a player takes as its input a strategy profile (that is a specification of strategies for every player) and yields a representation of payoff as its output.

An example

[edit]Player 2 Player 1 |

Left | Right |

|---|---|---|

| Top | 4, 3 | −1, −1 |

| Bottom | 0, 0 | 3, 4 |

The matrix provided is a normal-form representation of a game in which players move simultaneously (or at least do not observe the other player's move before making their own) and receive the payoffs as specified for the combinations of actions played. For example, if player 1 plays top and player 2 plays left, player 1 receives 4 and player 2 receives 3. In each cell, the first number represents the payoff to the row player (in this case player 1), and the second number represents the payoff to the column player (in this case player 2).

Other representations

[edit]

Often, symmetric games (where the payoffs do not depend on which player chooses each action) are represented with only one payoff. This is the payoff for the row player. For example, the payoff matrices on the right and left below represent the same game.

|

|

The topological space of games with related payoff matrices can also be mapped, with adjacent games having the most similar matrices. This shows how incremental incentive changes can change the game.

Uses of normal form

[edit]Dominated strategies

[edit]Player 2 Player 1 |

Cooperate | Defect |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperate | −1, −1 | −5, 0 |

| Defect | 0, −5 | −2, −2 |

The payoff matrix facilitates elimination of dominated strategies, and it is usually used to illustrate this concept. For example, in the prisoner's dilemma, we can see that each prisoner can either "cooperate" or "defect". If exactly one prisoner defects, he gets off easily and the other prisoner is locked up for a long time. However, if they both defect, they will both be locked up for a shorter time. One can determine that Cooperate is strictly dominated by Defect. One must compare the first numbers in each column, in this case 0 > −1 and −2 > −5. This shows that no matter what the column player chooses, the row player does better by choosing Defect. Similarly, one compares the second payoff in each row; again 0 > −1 and −2 > −5. This shows that no matter what row does, column does better by choosing Defect. This demonstrates the unique Nash equilibrium of this game is (Defect, Defect).

Sequential games in normal form

[edit]

Player 2 Player 1 |

Left, Left | Left, Right | Right, Left | Right, Right |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top | 4, 3 | 4, 3 | −1, −1 | −1, −1 |

| Bottom | 0, 0 | 3, 4 | 0, 0 | 3, 4 |

These matrices only represent games in which moves are simultaneous (or, more generally, information is imperfect). The above matrix does not represent the game in which player 1 moves first, observed by player 2, and then player 2 moves, because it does not specify each of player 2's strategies in this case. In order to represent this sequential game we must specify all of player 2's actions, even in contingencies that can never arise in the course of the game. In this game, player 2 has actions, as before, Left and Right. Unlike before he has four strategies, contingent on player 1's actions. The strategies are:

- Left if player 1 plays Top and Left otherwise

- Left if player 1 plays Top and Right otherwise

- Right if player 1 plays Top and Left otherwise

- Right if player 1 plays Top and Right otherwise

On the right is the normal-form representation of this game.

General formulation

[edit]In order for a game to be in normal form, we are provided with the following data:

There is a finite set I of players, each player is denoted by i. Each player i has a finite k number of pure strategies

A pure strategy profile is an association of strategies to players, that is an I-tuple

such that

A payoff function is a function

whose intended interpretation is the award given to a single player at the outcome of the game. Accordingly, to completely specify a game, the payoff function has to be specified for each player in the player set I= {1, 2, ..., I}.

Definition: A game in normal form is a structure

where:

is a set of players,

is an I-tuple of pure strategy sets, one for each player, and

is an I-tuple of payoff functions.

References

[edit]- Fudenberg, D.; Tirole, J. (1991). Game Theory. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-06141-4.

- Leyton-Brown, Kevin; Shoham, Yoav (2008). Essentials of Game Theory: A Concise, Multidisciplinary Introduction. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59829-593-1.. An 88-page mathematical introduction; free online at many universities.

- Luce, R. D.; Raiffa, H. (1989). Games and Decisions. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-65943-7.

- Shoham, Yoav; Leyton-Brown, Kevin (2009). Multiagent Systems: Algorithmic, Game-Theoretic, and Logical Foundations. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89943-7.. A comprehensive reference from a computational perspective; see Chapter 3. Downloadable free online.

- Weibull, J. (1996). Evolutionary Game Theory. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-23181-6.

- J. von Neumann and O. Morgenstern, Theory of games and Economic Behavior, John Wiley Science Editions, 1964. Which was originally published in 1944 by Princeton University Press.

Normal-form game

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition

A normal-form game, also known as a strategic-form game, is a core model in game theory that describes strategic interactions among a set of rational players who select actions simultaneously, without observing others' choices, to determine outcomes based on payoffs. This representation captures static decision-making under interdependence, where each player's payoff depends on the collective strategy profile chosen by all participants.[5] Key characteristics of a normal-form game include complete information, where all players possess full knowledge of the game structure, including available strategies and payoff mappings; strategy sets that may be finite or infinite, accommodating discrete or continuous choices; and a non-cooperative setting, in which players act independently to maximize their individual utilities without enforceable commitments. These features distinguish normal-form games from dynamic models like extensive-form games, which incorporate sequential moves and information revelation.[1] Unlike cooperative games, which allow for binding agreements and coalition formation to achieve joint outcomes, normal-form games emphasize individual rationality and potential self-interested conflicts, precluding enforceable side payments or contracts. The foundational framework was established by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, who formalized it as a tool for analyzing economic and strategic behavior. In standard notation, a normal-form game involves n players, indexed by i = 1 to n, each with a strategy set S_i denoting the possible actions available to player i. Payoff functions then assign real-valued utilities to each combination of strategies across all players.[2]Historical Context

The concept of the normal-form game traces its origins to early 20th-century efforts to formalize strategic decision-making in mathematics. In 1921, French mathematician Émile Borel introduced ideas related to the minimax theorem in the context of games like poker, laying preliminary groundwork for analyzing strategic interactions through probabilistic strategies, though without a fully rigorous proof.[6] This work anticipated the structured representation of player choices and outcomes but remained focused on specific game types. John von Neumann advanced these ideas significantly in his 1928 paper "Zur Theorie der Gesellschaftsspiele," where he proved the minimax theorem for two-person zero-sum games and introduced the normal form as a matrix-based representation of strategies and payoffs, establishing a foundational framework for game theory.[7] Building on this, von Neumann collaborated with economist Oskar Morgenstern to publish "Theory of Games and Economic Behavior" in 1944, which expanded the normal-form approach to broader economic contexts, incorporating utility theory and demonstrating its applicability beyond pure zero-sum scenarios.[8] Following World War II, the normal-form game gained prominence in operations research and economics, driven by wartime applications in strategic planning and postwar efforts to model economic competition and resource allocation.[9] In 1950 and 1951, John Nash extended the framework to non-zero-sum games through his development of the Nash equilibrium concept, which identified stable strategy profiles in normal-form representations where no player benefits from unilateral deviation.[10] Later refinements, such as those by Jean-François Mertens in the 1980s, addressed stability issues in these equilibria, providing criteria for strategically robust outcomes in normal-form games.Components and Formulation

Players and Strategies

In a normal-form game, the players form a finite set of rational decision-makers, typically denoted by , where each player seeks to maximize their own payoff given the actions of others.[11] This setup assumes simultaneous decision-making without binding commitments, distinguishing it from extensive-form representations.[8] Each player has a set of pure strategies , consisting of all possible complete plans of action available to them in the game.[12] A pure strategy specifies a definite choice for player , such as selecting a specific move without randomization. The collection of pure strategies across all players forms the strategy space , and a strategy profile represents a specific combination where for each .[11] To capture uncertainty or imperfect information, players may employ mixed strategies, which are probability distributions over their pure strategies. For player , a mixed strategy assigns probabilities such that , allowing randomization across actions.[13] A mixed strategy profile is then , where each is independent of the others, enabling analysis of equilibria that may not exist in pure strategies alone.[10] Normal-form games often feature finite strategy spaces, particularly discrete choices, as in rock-paper-scissors, where each player's , yielding possible pure strategy profiles for players.[12] However, strategy spaces can be infinite, such as compact intervals like in the tragedy of the commons, where players choose extraction levels continuously, or unbounded sets like in Cournot competition, where firms select output quantities.[11][14] Finite cases guarantee the existence of mixed-strategy Nash equilibria, while infinite spaces require additional compactness or continuity assumptions for similar results.[10]Payoff Functions

In a normal-form game, the payoff function for each player (where is the set of players) is denoted , which assigns a real-valued utility to every strategy profile (the Cartesian product of all players' strategy sets).[1] This function quantifies the outcome of the game from player 's perspective, capturing preferences over possible results.[15] Payoff functions are typically interpreted through von Neumann-Morgenstern (vNM) utility theory, which provides a cardinal representation of preferences under uncertainty. Unlike ordinal utilities, which only rank outcomes without measuring intensity, vNM utilities are unique up to positive affine transformations and enable the computation of expected utilities for lotteries or mixed strategies.[11] For a mixed strategy profile , where each is a probability distribution over player 's strategies, player 's expected payoff is given by This formulation arises from the vNM axioms of completeness, transitivity, continuity, and independence, ensuring that rational agents maximize expected utility. Games are classified as zero-sum if the sum of payoffs across all players is zero for every strategy profile, i.e., for all , implying pure conflict where one player's gain equals another's loss. In contrast, non-zero-sum games allow for variable total payoffs, enabling cooperation or mutual benefit, as the sum can differ across profiles.[1] Standard normal-form game analysis assumes common knowledge of all payoff functions, meaning every player knows the payoffs, knows that others know them, and so on ad infinitum.[16] Additionally, players are assumed rational, seeking to maximize their expected payoffs given beliefs about others' actions.[17] These assumptions underpin the strategic evaluation of outcomes in normal-form games.[11]Representations

Matrix Representation

The matrix representation, often called the bimatrix form, is a tabular method used to visualize normal-form games involving exactly two players with finite strategy sets. In this format, the rows represent the pure strategies available to player 1, while the columns represent those of player 2. Each entry in the resulting matrix consists of an ordered pair , where and denote the payoffs to player 1 and player 2, respectively, for the joint strategy profile .[18][1] Consider a simple case where player 1 has strategies labeled A and B, and player 2 has strategies X and Y. The bimatrix takes the following structure:| X | Y | |

|---|---|---|

| A | ||

| B |

Strategic Form Tuple

The strategic form provides a compact mathematical representation of a normal-form game, encapsulating its essential elements in tuple notation. Formally, a normal-form game in strategic form is defined as the tuple , where is a finite set of players, denotes the strategy set available to player , and is the payoff function assigning a real-valued payoff to each strategy profile for player . This formulation, introduced in the foundational work on noncooperative games, allows for arbitrary finite or infinite strategy sets and any number of players , providing a general framework beyond the two-player case. To incorporate uncertainty and randomization, the strategic form extends to mixed strategies via the tuple , where is the set of mixed strategies for player , consisting of all probability distributions over the pure strategies in , and is the expected utility function defined as for a mixed strategy profile , where the expectation is taken with respect to the product distribution induced by (reducing to a summation for finite ).[12] This extension preserves the structure of the original game while enabling analysis of equilibria involving randomization, as mixed strategies induce expected payoffs linear in the probabilities. The pure strategy game and its mixed extension are isomorphic in the sense that pure strategies correspond to degenerate mixed strategies (Dirac distributions on singletons in ), ensuring that solution concepts like Nash equilibrium defined on restrict appropriately to pure strategy profiles in . This isomorphism underscores the generality of the tuple notation, which contrasts with matrix representations limited to finite two-player games by facilitating theoretical extensions to broader classes of interactions.[21]Examples

Prisoner's Dilemma

The Prisoner's Dilemma is a foundational example in normal-form game theory, originally formulated by RAND Corporation researchers Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher in 1950 to explore non-cooperative decision-making, and later named by mathematician Albert Tucker to evoke a criminal interrogation scenario.[22] In this setup, two suspects are arrested for a crime and held in isolation, unable to communicate. Each must independently choose whether to remain silent (cooperate with the other prisoner by not betraying them) or confess (defect by implicating the partner). The outcomes depend on their joint choices, with payoffs measured in years of prison time (lower values are preferable, often converted to utilities where higher numbers indicate better outcomes, such as reduced sentence length).[22] The standard payoff structure assigns the following prison sentences: if both remain silent, each serves 1 year; if one confesses while the other remains silent, the confessor goes free (0 years) and the silent one serves 3 years; if both confess, each serves 2 years.[22] Represented as a normal-form payoff matrix with utilities (negative values for years served, higher utility better), the game for Player 1 (rows) and Player 2 (columns) is:| Player 2 \ Player 1 | Silent (Cooperate) | Confess (Defect) |

|---|---|---|

| Silent (Cooperate) | -1, -1 | -3, 0 |

| Confess (Defect) | 0, -3 | -2, -2 |

Coordination Game

A coordination game is a type of normal-form game in which players' interests align such that they all benefit from selecting the same strategy, with the primary challenge being to achieve mutual alignment without communication.[24] Unlike games of pure conflict, coordination games feature payoffs that reward synchronization, often resulting in multiple stable outcomes where deviation by any player reduces everyone's welfare. A classic example of a pure coordination game involves two drivers approaching each other on a narrow road, each deciding simultaneously whether to swerve left or right to avoid collision. If both choose the same direction, they pass safely with high payoffs; if they choose differently, they collide with low payoffs. The symmetric payoff matrix for this game, where payoffs represent utilities (higher for success, lower for failure), is as follows:| Driver 1 \ Driver 2 | Left | Right |

|---|---|---|

| Left | 1, 1 | 0, 0 |

| Right | 0, 0 | 1, 1 |

| Husband \ Wife | Opera | Fight |

|---|---|---|

| Opera | 2, 1 | 0, 0 |

| Fight | 0, 0 | 1, 2 |

Solution Concepts

Dominated Strategies

A strategy for player in a normal-form game strictly dominates another strategy if it yields a payoff for every strategy profile of the opponents, with strict inequality holding for at least one such profile. This condition implies that no rational player would ever choose the dominated strategy , as the dominating strategy is always at least as good and sometimes better, regardless of others' actions. Weak dominance relaxes the strict inequality requirement, allowing equality in all cases but still prohibiting the weakly dominated strategy under common knowledge of rationality. The iterated elimination of strictly dominated strategies (IESDS) is a procedure that successively removes strictly dominated strategies from the game, updating the strategy sets after each round until no further eliminations are possible. This stepwise reduction simplifies the game while preserving the set of rationalizable outcomes, as each elimination step reflects the belief that rational players avoid inferior choices. In finite games, IESDS is order-independent, meaning the final reduced game is unique regardless of the sequence of eliminations. Rationalizability refers to the solution concept obtained as the limit of infinite iterations of strict dominance elimination in finite normal-form games, capturing all strategy profiles consistent with common knowledge of rationality among players.[25] Introduced independently by Bernheim and Pearce, rationalizable strategies form a refinement that eliminates implausible choices beyond what a single round of dominance might achieve, though it may not yield a unique outcome.[26] To illustrate, consider the following generic 2x2 normal-form game with players Row and Column, each having strategies A/B and X/Y, respectively:| X | Y | |

|---|---|---|

| A | 3, 0 | 2, 1 |

| B | 1, 2 | 0, 3 |

| X | Y | |

|---|---|---|

| A | 3, 0 | 2, 1 |

Nash Equilibrium

In a normal-form game, a Nash equilibrium is a strategy profile where no player can improve their expected payoff by unilaterally changing their strategy, assuming the other players' strategies remain fixed. Formally, is a Nash equilibrium if, for every player , is a best response to , i.e., for all pure strategies , and every pure strategy with positive probability under achieves this maximum payoff.[27] John Nash proved the existence of at least one Nash equilibrium (possibly mixed) for every finite normal-form game with a finite number of players and actions, relying on Brouwer's fixed-point theorem applied to a continuous best-response correspondence over the simplex of mixed strategies.[27] This result holds even for games without pure-strategy equilibria, such as matching pennies, where players must randomize to prevent exploitation.[27] A pure-strategy Nash equilibrium occurs when each player assigns probability 1 to a single pure strategy in the profile, satisfying the best-response condition deterministically; in contrast, a mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium involves players randomizing over multiple pure strategies with positive probability.[27] While pure equilibria are simpler to interpret, mixed ones are necessary for equilibrium in games with inherent conflict, and Nash's theorem guarantees their existence in finite games.[27] To compute Nash equilibria, methods like best-response dynamics iteratively update each player's strategy to their current best response against the others' strategies, potentially converging to a pure equilibrium in potential games or under certain conditions, though cycles can occur in general.[28] This approach highlights the equilibrium's role as a steady state of such adjustment processes. Nash equilibria possess stability against unilateral deviations by construction, making them robust to individual perturbations in non-cooperative settings.[27] However, they are not necessarily Pareto efficient, as outcomes may exist where all players are better off; for instance, in the Prisoner's Dilemma, the unique Nash equilibrium of mutual defection is Pareto dominated by mutual cooperation.[29]Relation to Extensive-Form Games

Conversion Between Forms

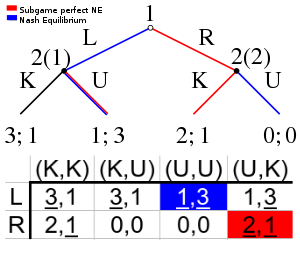

The normal form of an extensive-form game is obtained by defining each player's strategy as a complete contingent plan that specifies an action for every information set controlled by that player, with payoffs calculated as the expected values derived from the outcomes of all possible strategy profiles leading to terminal histories.[30] This reduction process transforms the sequential structure into a simultaneous-move representation, where the strategy set for each player consists of all such behavioral plans.[1] In extensive-form games with imperfect information, information sets partition the decision nodes into groups where the player cannot distinguish between histories; strategies must therefore assign the same action to all nodes within each information set, which expands the normal-form strategy space relative to the extensive form's sequential choices and can lead to exponentially larger matrices.[30] For instance, in games where a player observes partial signals, the contingent plans must cover all possible realizations consistent with the information set, ensuring consistency across indistinguishable paths. While the normal form fully captures the set of possible outcomes and expected payoffs from any strategy profile in the extensive form, it discards the temporal ordering of moves and subgame structure, potentially obscuring refinements like subgame perfection that rely on sequential rationality.[30] Nash equilibria in this induced normal form identify strategy profiles that are stable under simultaneous play but may include non-credible threats when interpreted sequentially.[31] A classic illustration is the entry deterrence game, where the potential entrant moves first to Enter or Stay Out; if Enter, the incumbent then chooses Accommodate (yielding duopoly payoffs of 15 for each) or Fight (yielding -1 for each), while Stay Out gives the entrant 0 and the incumbent monopoly profit of 35.[31] Converting to normal form yields the following payoff matrix, with the entrant's strategies as rows and the incumbent's contingent plans as columns:| Entrant \ Incumbent | Accommodate | Fight |

|---|---|---|

| Enter | 15, 15 | -1, -1 |

| Stay Out | 0, 35 | 0, 35 |