Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

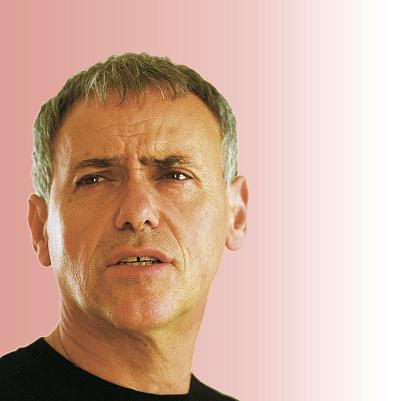

Ariel Rubinstein

View on WikipediaAriel Rubinstein (Hebrew: אריאל רובינשטיין; born April 13, 1951) is an Israeli economist who works in economic theory, game theory and bounded rationality.

Key Information

Biography

[edit]Ariel Rubinstein is a professor of economics at the School of Economics at Tel Aviv University and the Department of Economics at New York University. He studied mathematics and economics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1972–1979 (B.Sc. Mathematics, Economics and Statistics, 1974; M.A. Economics, 1975; M.Sc Mathematics, 1976; Ph.D. Economics, 1979).

In 1982, he published "Perfect equilibrium in a bargaining model",[1] an important contribution to the theory of bargaining. The model is known also as a Rubinstein bargaining model. It describes two-person bargaining as an extensive game with perfect information in which the players alternate offers. A key assumption is that the players are impatient. The main result gives conditions under which the game has a unique subgame perfect equilibrium and characterizes this equilibrium.

Relevance of game theory

[edit]Rubinstein has argued against the relevance of game theory to practical decision-making. He characterizes game theory as a way to abstractly describe idealized strategic situations stripped of details, but says this is useless in real life, where many details are relevant. He reports "I have not seen, in all my life, a single example where a game theorist could give advice, based on the theory, which was more useful than that of the layman."[2]

some contend that the Euro Bloc crisis is like the games called Prisoner's Dilemma, Chicken, or Diner's Dilemma. The crisis indeed includes characteristics that are reminiscent of each of these situations. But such statements include nothing more profound than saying that the euro crisis is like a Greek tragedy. While the comparison to a Greek tragedy is seen as an emotional statement by detached intellectuals, the assignment of a label from the vocabulary of game theory is, for some reason, accepted as scientific truth.[3]

Honours and awards

[edit]Rubinstein was elected a member of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities (1995),[4] a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in (1994)[5] and the American Economic Association (1995). In 1985 he was elected a fellow of the Econometric Society,[6] and served as its president in 2004.[7]

In 2002, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Tilburg University.[8]

He has received the Bruno Prize (2000), the Israel Prize for economics (2002),[9][10] the Nemmers Prize in Economics (2004),[11][12] the EMET Prize (2006).[13] and the Rothschild Prize (2010).[14]

Published works

[edit]- Bargaining and Markets, with Martin J. Osborne, Academic Press 1990

- A Course in Game Theory, with Martin J. Osborne, MIT Press, 1994.

- Modeling Bounded Rationality, MIT Press, 1998.

- Economics and Language, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Lecture Notes in Microeconomic Theory: The Economic Agent, Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Economic Fables, Open Book Publishers, 2012.

- AGADOT HAKALKALA, in Hebrew, Kineret, Zmora, Bitan, 2009.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Rubinstein, Ariel (1982). "Perfect Equilibrium in a Bargaining Model" (PDF). Econometrica. 50 (1): 97–109. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.295.1434. doi:10.2307/1912531. JSTOR 1912531. S2CID 14827857.

- ^ Roell, Sophie (6 December 2016). "The best books on Game Theory". Five Books (Interview). London: Fivebooks Limited. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ^ Rubinstein, Ariel (27 March 2013). "How game theory will solve the problems of the Euro Bloc and stop Iranian nukes". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2013.

- ^ "Prof. Rubinstein Ariel Member Information (Election year 1995)". Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter R" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Welcome to the website of The Econometric Society An International Society for the Advancement of Economic Theory in its Relation to Statistics and Mathematics Archived December 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Welcome to the website of The Econometric Society An International Society for the Advancement of Economic Theory in its Relation to Statistics and Mathematics Archived October 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tilburg University - Search results". Tilburg University.

- ^ "Israel Prize Official Site (in Hebrew) – Recipient's C.V."

- ^ "Israel Prize Official Site (in Hebrew) – Judges' Rationale for Grant to Recipient".

- ^ Nemmers Prizes, Awards, Office of the Provost, Northwestern University Archived September 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Erwin Plein Nemmers Prize in Economics". Archived from the original on February 22, 2006.

- ^ "סיעוד". Archived from the original on 2007-03-11.

- ^ "Rothschild Prize".

External links

[edit]Ariel Rubinstein

View on GrokipediaBiography

Early Life and Education

Ariel Rubinstein was born on April 13, 1951, in Jerusalem, Israel, where he acquired Israeli citizenship.[1] Details about his family background remain limited in public records.[4] Rubinstein pursued his undergraduate and graduate studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem from 1972 to 1979. He earned a B.Sc. in Mathematics, Economics, and Statistics in 1974, followed by an M.A. in Economics in 1975 under the supervision of Menahem Yaari.[1] In 1976, he obtained an M.Sc. in Mathematics supervised by Bezalel Peleg, and he completed his Ph.D. in Economics in 1979, again under Yaari's guidance.[1]Academic Career

Rubinstein began his academic career at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where he was appointed Senior Lecturer in the Department of Economics in October 1981, promoted to Associate Professor in October 1984, and advanced to Full Professor in October 1986, holding the position until March 1990.[1] In April 1990, he joined Tel Aviv University as Professor in the Department of Economics, a role he maintained until September 2019, during which he also held the Salzberg Chair in Economics from May 1990 to September 2019.[1] From July 1991 to May 1993, Rubinstein served as Chairperson of the Department of Economics at Tel Aviv University, contributing to its administrative leadership.[1] Upon retiring from his full professorship at Tel Aviv University, he was granted emeritus status in the School of Economics.[5] Concurrently, Rubinstein held international appointments that expanded his global academic influence. From 1991 to 2004, he served as Lecturer in the Rank of Professor at Princeton University, and since September 2004, he has been Professor of Economics at New York University, where he continues to hold the position.[1][6] In recent years, Rubinstein has remained active in international scholarly engagements, delivering the plenary lecture at the 2023 Asian Meeting of the Econometric Society (AMES) in Mumbai and the Morgenstern Lecture at the 7th World Congress of the Game Theory Society in Beijing in 2024.[1][7]Contributions to Economic Theory

Bargaining and Negotiation Models

Ariel Rubinstein's seminal contribution to bargaining theory is the alternating-offers bargaining model, introduced in 1982, which analyzes a two-player game where agreement must be reached over the division of a fixed resource, often normalized to a "pie" of size 1.[8] In this infinite-horizon setup, players alternate making offers and counteroffers, with rejection leading to continued bargaining in the next period; time is discrete, and each player discounts future payoffs by a factor δ_i (where 0 < δ_i < 1 for player i=1,2), reflecting impatience or the cost of delay.[8] The model assumes complete information, perfect rationality, and that offers are public, culminating in a unique subgame perfect equilibrium where agreement is reached immediately upon the first offer.[8] This equilibrium is derived by backward induction in the infinite-horizon structure, ensuring consistency across all subgames. Player 1, who makes the initial offer, proposes a division that leaves player 2 indifferent between accepting and rejecting to make a counteroffer; the equilibrium payoffs are thus \frac{1 - \delta_2}{1 - \delta_1 \delta_2} for player 1 and \frac{\delta_2 (1 - \delta_1)}{1 - \delta_1 \delta_2} for player 2, summing to 1.[8] These payoffs favor the first mover but approach equality as discount factors increase (i.e., as players become more patient), highlighting the role of timing and patience in bargaining power.[8] The model was published as "Perfect Equilibrium in a Bargaining Model" in Econometrica.[8] The infinite-horizon framework resolves paradoxes arising in finite-horizon bargaining games, where multiple subgame perfect equilibria exist due to endgame effects—such as the last-period ultimatum leading to unraveling—but converge to Rubinstein's unique outcome as the horizon lengthens indefinitely.[8] This provides a robust foundation for non-cooperative bargaining theory, avoiding arbitrary assumptions about finite bargaining length. Rubinstein's model has profoundly influenced economic analysis through extensions to multi-player settings, incomplete information, and stochastic environments, as detailed in collaborative work.[9] It has been applied to model decentralized markets, where bilateral bargaining approximates competitive outcomes under specific conditions on matching and patience; to contract theory, explaining hold-up problems and renegotiation; and to labor markets, deriving wage determination in search-and-bargaining frameworks like the Diamond-Mortensen-Pissarides model.[9] In real-world negotiations, such as international treaties or corporate mergers, the model underscores how alternating proposals and time pressure shape efficient, immediate settlements.[10]Bounded Rationality and Game Theory

Rubinstein's work on bounded rationality challenges the standard game-theoretic assumption of perfect rationality by explicitly modeling the procedural and cognitive limitations of decision-makers, incorporating instinctive and emotional responses alongside deliberate reasoning. In his influential book Modeling Bounded Rationality (1998), he defines these models as frameworks that embed the elements of the choice process—such as limited information processing and heuristic-based decisions—directly into the analysis of strategic interactions, allowing for a more realistic depiction of economic behavior under uncertainty. This approach underscores how boundedly rational agents may deviate from optimal outcomes due to cognitive constraints, providing a foundation for understanding real-world deviations from equilibrium predictions.[11] A prominent example of Rubinstein's contributions is the Electronic Mail Game, introduced in his 1989 paper, which illustrates the fragility of coordination when common knowledge is only "almost" established due to imperfect communication. In this two-player game, players A and B must choose between a safe action (A) or a risky coordinating action (B), where payoffs favor coordination if a specific state holds (yielding 1 for both), but mismatch or safe play in that state incurs losses (-L for the deviator, 0 otherwise). A machine sends an initial message to A indicating the state, who then confirms receipt back to the machine, which relays it to B; each transmission succeeds with probability 1-ε (where ε > 0 is small). Confirmations continue iteratively until failure, but despite arbitrarily high probabilities of successful multi-stage communication, the unique Nash equilibrium requires infinite confirmations for coordination, which occurs with probability zero, leading to persistent inefficient safe play. This paradox highlights how even negligible risks undermine common knowledge, a core requirement for efficient equilibria in classical game theory.[12] Rubinstein further advanced this line of research in his 2007 paper "Instinctive and Cognitive Reasoning: A Study of Response Times," where he develops a typology distinguishing instinctive players (who rely on rapid, emotion-driven heuristics) from cognitive players (who engage in slower, analytical deliberation). Using experimental tasks presented to lecture audiences and students, he measures response times to infer reasoning types, finding that instinctive choices correlate with shorter times and emotional framing, while cognitive choices involve longer deliberation and logical consistency. This empirical framework supports bounded rationality by classifying decision-makers and predicting behavior based on their dominant reasoning mode, offering tools to model heterogeneous strategic interactions.[13] These innovations have profoundly influenced experimental economics and analyses of decision-making under uncertainty, with the Electronic Mail Game serving as a benchmark for studying coordination failures in communication-limited environments. Experimental implementations, such as those varying message costs and strategic transmission, have tested the game's predictions, often revealing partial coordination beyond theoretical equilibria due to boundedly rational shortcuts, thus bridging theory and observed behavior in real settings.[14]Methodological Critiques

Ariel Rubinstein has offered pointed critiques of game theory, arguing that it frequently lacks practical predictive power and functions more as a mathematical exercise than a reliable tool for understanding or influencing real-world behavior. In a 2011 interview, he emphasized that game theory's successes are often overstated due to academic incentives, and it fails to produce testable predictions or actionable solutions for public policy problems. This perspective aligns with his broader view that economic modeling prioritizes logical elegance over empirical relevance, leading to abstractions that do not capture intuitive human decision-making. In key reflective works, Rubinstein delves into the methodological tensions inherent in economic theorizing. His 2006 paper "Dilemmas of an Economic Theorist" outlines four core dilemmas: whether to discard models yielding absurd conclusions, such as inconsistent preferences; how to respond to contradictory experimental evidence; the need for formal models to discern behavioral regularities; and the theorist's capacity to offer relevant real-world advice. These discussions underscore his skepticism toward over-formalization, advocating instead for models that prioritize intuitive storytelling and fables to illuminate economic insights without relying excessively on mathematical rigor. Similarly, in his 2015 paper "Back to Fundamentals: Equilibrium in Abstract Economies," co-authored with Michael Richter, Rubinstein critiques the hidden algebraic assumptions in traditional equilibrium concepts, proposing more primitive, abstract definitions to reveal the limitations of standard game-theoretic frameworks. Rubinstein's methodological stance favors "economic fables" to convey behavioral realism over hyper-rational, fully specified models that assume perfect foresight and consistency. In his 2012 book Economic Fables, he employs personal anecdotes and narrative examples to explore microeconomic ideas, arguing that such intuitive approaches better reflect real-life complexities than detached formalism, while challenging the field's tendency to ignore non-academic perspectives. This rejection of overly rational paradigms stems from his observation that economic theory often produces insights through simplified stories rather than predictive equations. More recently, in the 2024 paper "Making Predictions Based on Data: Holistic and Atomistic Procedures," co-authored with Jacob Glazer, Rubinstein investigates empirical prediction methods, finding that individuals predominantly use holistic procedures—predicting based on overall patterns in small data samples—rather than atomistic breakdowns aligned with theoretical models. This work highlights the disconnect between theoretical economics and actual data-driven forecasting, favoring empirical realism over abstract theorizing. These critiques have informed Rubinstein's constructive efforts in bounded rationality, where models incorporate procedural limitations to remedy game theory's identified shortcomings.Publications

Major Books

Rubinstein's major books synthesize his research into accessible yet rigorous treatments of core economic concepts, often building on his journal articles to provide pedagogical frameworks for advanced students and scholars. These works emphasize analytical models while critiquing traditional assumptions, influencing curricula in game theory, microeconomics, and behavioral economics. "Bargaining and Markets," co-authored with Martin J. Osborne and published in 1990 by Academic Press, explores the formation of markets through bilateral bargaining models, using extensive-form games to analyze how trading procedures and anonymity affect outcomes in decentralized economies.[15] Aimed at graduate students and researchers in economic theory, the book extends Nash's bargaining solution by incorporating time and strategic interactions, offering foundational insights into non-cooperative bargaining that have shaped subsequent studies on market microstructure and contract theory.[15] "A Course in Game Theory," co-authored with Martin J. Osborne and published in 1994 by MIT Press, serves as a comprehensive textbook on non-cooperative game theory, covering Nash equilibrium, subgame perfection, and repeated games at a level suitable for graduate students and advanced undergraduates.[16] It emphasizes intuitive explanations alongside formal proofs, making complex strategic interactions accessible without requiring advanced mathematics, and has become a standard reference in economics and political science courses worldwide.[16] "Modeling Bounded Rationality," published in 1998 by MIT Press as part of the Zeuthen Lecture Book Series, collects Rubinstein's essays on incorporating cognitive limitations into decision-making models, focusing on procedural rationality rather than full optimization in both individual choice and games.[17] Targeted at economists interested in behavioral foundations, the book highlights challenges in modeling imperfect information processing and has influenced the shift toward psychologically realistic theories in economic analysis.[17] "Economics and Language: Five Essays," published in 2000 by Cambridge University Press, examines the interplay between linguistic structures and economic modeling, using game-theoretic tools to analyze how conversational rules and semantics inform rational choice and signaling.[18] Drawing from the Churchill Lectures, it appeals to interdisciplinary audiences in economics and linguistics, offering novel perspectives on the "language of economics" that have inspired research at the nexus of formal semantics and strategic interaction.[18] "Economic Fables," published in 2012 by Open Book Publishers, employs narrative parables to illustrate economic principles like incentives, equilibrium, and social norms, blending memoir with theoretical exposition to make abstract ideas engaging for a broad readership including students and general economists.[19] This innovative approach critiques overly mathematical economics while reinforcing conceptual understanding, establishing it as a unique pedagogical tool that encourages critical thinking about model assumptions.[19] "Models in Microeconomic Theory," co-authored with Martin J. Osborne and published in 2020 by Open Book Publishers (with an expanded second edition in 2023), presents a collection of advanced models in consumer theory, producer theory, and general equilibrium, emphasizing precise formulations and proofs for graduate-level instruction.[20] Designed for PhD students, it prioritizes conceptual clarity over empirical applications, serving as a modern supplement to traditional microeconomics texts by focusing on equilibrium analysis and strategic elements.[20] "No Prices No Games!: Four Economic Models," co-authored with Michael Richter, first edition published in April 2024 and second edition in November 2024 by Open Book Publishers, critiques reliance on price mechanisms and game theory by proposing alternative models based on conventions like jungle equilibria, permissibility norms, status hierarchies, and indoctrination.[21] Intended for theorists questioning mainstream paradigms, the book uses simple mathematical frameworks to explore non-market coordination, contributing to ongoing debates on the limits of formal economic modeling.[21]Key Journal Articles

Ariel Rubinstein has authored over 110 journal articles throughout his career, with selections here focusing on high-impact works based on citation counts and influence in economic theory.[22][23] One of his most seminal contributions is "Perfect Equilibrium in a Bargaining Model," published in Econometrica in 1982, which introduces the alternating-offers bargaining model and establishes a unique subgame perfect equilibrium under complete information. This paper has garnered over 8,400 citations and forms the foundation for much of modern bargaining theory.[24] Another influential work is "The Electronic Mail Game: Strategic Behavior Under 'Almost Common Knowledge'," appearing in the American Economic Review in 1989, which demonstrates a coordination failure paradox arising from incomplete common knowledge in a communication setup. With over 900 citations, it has profoundly shaped discussions on knowledge and strategic interaction in game theory.[25] Earlier, "Equilibrium in Supergames with the Overtaking Criterion," in the Journal of Economic Theory in 1979, analyzes equilibria in infinitely repeated games using an overtaking optimality criterion, contributing to the study of long-run cooperation. It has received over 600 citations and remains a key reference in repeated games literature.[26] In more recent years, Rubinstein's output includes "A Typology of Players: Between Instinctive and Contemplative," published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics in 2016, which proposes a classification of decision-makers based on response times to distinguish instinctive from contemplative behaviors in experimental settings. Collaborating with Ayala Arad, he co-authored "The People's Perspective on Libertarian-Paternalistic Policies" in the Journal of Law and Economics in 2018, an experimental study revealing public attitudes toward soft governmental interventions like defaults and nudges. From 2024, "Unilateral Stability in Matching Problems," co-authored with Michael Richter in the Journal of Economic Theory, explores a new stability concept in matching markets where deviations require unilateral action by one side.[27] Also in 2024, "People Making Predictions Based on Data: Holistic and Atomistic Procedures," with Jacob Glazer in the Journal of Economic Theory, contrasts holistic and piecemeal approaches to data-based forecasting in decision-making.Awards and Honors

Rubinstein has received numerous awards and honors for his contributions to economic theory. These include:- Rothschild Fellow (1979)[1]

- Fellow of the Econometric Society (1985); served on the executive committee (1994–1997) and as President (2004)[1]

- Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1994)[1][3]

- Foreign Honorary Member of the American Economic Association (1995)[1]

- Fellow of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities (1995)[1]

- Michael Bruno Memorial Award (2000)[1]

- Israel Prize in Economics (2002)[1]

- Honorary Doctorate from Tilburg University (2002)[1]

- Honorary Fellow of Nuffield College, Oxford (2002)[1]

- Member of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts (2004)[1]

- Erwin Plein Nemmers Prize in Economics from Northwestern University (2004)[1]

- Fellow of the European Economic Association (2004)[1]

- EMET Prize (2006)[1]

- Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy (2007)[1]

- Rothschild Prize (2010)[1]

- Economic Theory Fellow (2011)[1]

- Member of Academia Europaea (2012)[1]

- Fellow of the Game Theory Society (2017)[1]

- Clarivate Analytics Citation Laureate (2019)[1]