Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

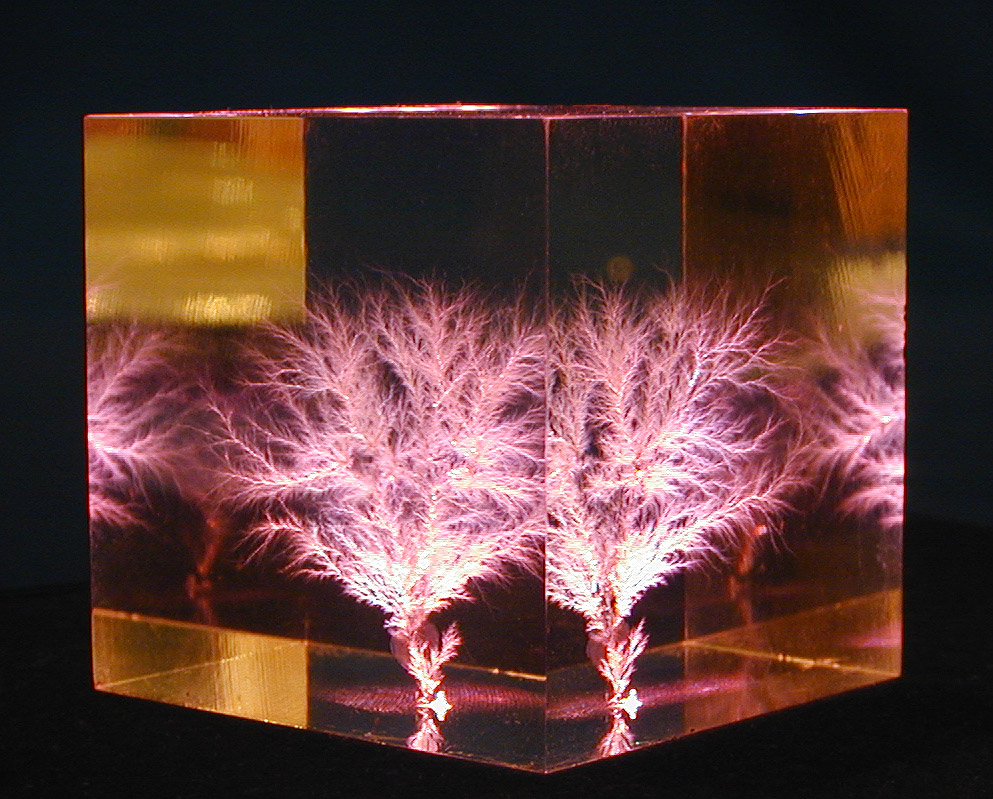

Electrical treeing

View on Wikipedia

In electrical engineering, treeing is an electrical pre-breakdown phenomenon in solid insulation. It is a damaging process due to partial discharges and progresses through the stressed dielectric insulation, in a path resembling the branches of a tree. Treeing of solid high-voltage cable insulation is a common breakdown mechanism and source of electrical faults in underground power cables.

Other occurrences and causes

[edit]Electrical treeing is typically initiated and then propagates when a dry dielectric material is subjected to high and divergent electrical field stress over a long period of time. Electrical treeing is observed to originate at points where impurities, gas voids, mechanical defects, or conducting projections cause excessive electrical field stress within small regions of the dielectric. This can ionize gases within voids inside the bulk dielectric, creating small electrical discharges between the walls of the void. An impurity or defect may even result in the partial breakdown of the solid dielectric itself. Ultraviolet light and ozone from these partial discharges (PD) then react with the nearby dielectric, decomposing and further degrading its insulating capability. Gases are often liberated as the dielectric degrades, creating new voids and cracks. These defects further weaken the dielectric strength of the material, enhance the electrical stress, and accelerate the PD process.

Water trees and electrical trees

[edit]In the presence of water, a diffuse, partially conductive 3D plume-like structure, called a water tree, may form within the polyethylene dielectric used in buried or water-immersed high voltage cables. The plume is known to consist of a dense network of extremely small water-filled channels which are defined by the native crystalline structure of the polymer. Individual channels are extremely difficult to see using optical magnification, so their study usually requires using a scanning electron microscope (SEM).

Water trees begin as a microscopic region near a defect. They then grow under the continued presence of a high electrical field and water. Water trees may eventually grow to the point where they bridge the outer ground layer to the center high voltage conductor, at which point the stress redistributes across the insulation. Water trees are not generally a reliability concern unless they are able to initiate an electrical tree.

Another type of tree-like structure can form with or without the presence of water is called an electrical tree. It also forms within a polyethylene dielectric (as well as many other solid dielectrics). Electrical trees also originate where bulk or surface stress enhancements initiate dielectric breakdown in a small, highly-stressed region of the insulation. This permanently damages the insulating material in that region. Further tree growth then occurs through as additional small electrical breakdown events (called partial discharges). Electrical tree growth may be accelerated by transient voltage changes or reversals, such as utility switching operations. Also, cables injected with high voltage DC may also develop electrical trees over time as electrical charges migrate into the dielectric nearest the HV conductor. The region of injected charge (called a space charge) amplifies the electrical field in the dielectric, stimulating further stress enhancement and the initiation of electrical trees as the site of pre-existing stress enhancements. Since the electrical tree itself is typically partially conducting, its presence also increases the electrical stress in the remaining region between the tree and the opposite conductor.

Unlike water trees, the individual channels of electrical trees are larger and more easily seen.[1][2] Treeing has been a long-term failure mechanism for buried polymer-insulated high voltage power cables, first reported in 1969.[3] In a similar fashion, 2D trees can occur along the surface of a highly stressed dielectric, or across a dielectric surface that has been contaminated by dust or mineral salts. Over time, these partially conductive trails can grow until they cause complete failure of the dielectric. Electrical tracking, sometimes called dry banding, is a typical failure mechanism for electrical power insulators that are subjected to salt spray contamination along coastlines. The branching 2D and 3D patterns are sometimes called Lichtenberg figures.

Electrical treeing or "Lichtenberg figures" also occur in high-voltage equipment just before breakdown. Following these Lichtenberg figures in the insulation during postmortem investigation of the broken down insulation can be most useful in finding the cause of breakdown. An experienced high-voltage engineer can see from the direction and the type of trees and their branches where the primary cause of the breakdown was situated and possibly find the cause. Broken-down transformers, high-voltage cables, bushings, and other equipment can usefully be investigated in this way; the insulation is unrolled (in the case of paper insulation) or sliced in thin slices (in the case of solid insulation systems), the results are sketched and photographed and form a useful archive of the breakdown process.

Types of electrical trees

[edit]Electrical trees can be further categorized depending on the different tree patterns. These include dendrites, branch type, bush type, spikes, strings, bow-ties and vented trees. The two most commonly found tree types are bow-tie trees and vented trees.[4]

- Bow-tie trees

- Bow-tie trees are trees which start to grow from within the dielectric insulation and grow symmetrically outwards toward the electrodes. As the trees start within the insulation, they have no free supply of air which will enable continuous support of partial discharges. Thus, these trees have discontinuous growth, which is why the bow-tie trees usually do not grow long enough to fully bridge the entire insulation between the electrodes, therefore causing no failure in the insulation.

- Vented trees

- Vented trees are trees which initiate at an electrode insulation interface and grow towards the opposite electrode. Having access to free air is a very important factor for the growth of the vented trees. These trees are able to grow continuously until they are long enough to bridge the electrodes, therefore causing failure in the insulation.

Detection and location of electrical trees

[edit]Electrical trees can be detected and located by means of partial discharge measurement.

As the measurement values of this method allow no absolute interpretation, data collected during the procedure is compared to measurement values of the same cable gathered during the test. This allows simple and quick classification of the dielectric condition (new, strongly aged, faulty) of the cable under test.

To measure the level of partial discharges, 50–60 Hz or sometimes a sinusoidal 0.1 Hz VLF (very low frequency) voltage may be used. The turn-on voltage, a major measurement criterion, can vary by over 100% between 50 and 60 Hz measurements as compared to 0.1 Hz VLF (very low frequency) Sinusoidal AC source at the power frequency (50–60 Hz) as mandated by IEEE standards 48, 404, 386, and ICEA standards S-97-682, S-94-649 and S-108-720. Modern PD-detection systems employ digital signal processing software for analysis and display of measurement results.

An analysis of the PD signals collected during the measurement with the proper equipment can allow for the vast majority of location of insulation defects. Usually they are displayed in a partial discharge mapping format. Additional useful information about the device under test can be derived from a phase related depiction of the partial discharges.

A sufficient measurement report contains:

- Calibration pulse (in accordance with IEC 60270) and end detection

- Background noise of the measurement arrangement

- Partial discharge inception voltage PDIV

- Partial discharge level at 1.7 Vo

- Partial discharge extinction voltage PDEV

- Phase-resolved partial discharge pattern PRPD for advanced interpretation of partial discharge behavior (optional)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ E. Moreau; C. Mayoux; C. Laurent (February 1993), "The Structural Characteristics of Water Trees in Power Cables and Laboratory Specimens", IEEE Transactions on Electrical Insulation, 28 (1), IEEE: 54–64, doi:10.1109/14.192240

- ^ Simmons, M. (2001). "Section 6.6.2". In Ryan, Hugh M. (ed.). High Voltage Engineering and Testing (Second ed.). The Institution of Electrical Engineers. p. 266. ISBN 0-85296-775-6.

- ^ T. Miyashita (1971), "Deterioration of Water-immersed Polyethylene Coated Wire by Treeing publication=Proceedings 1969 IEEE-NEMA Electrical Insulation Conference", IEEE Transactions on Electrical Insulation, EI-6 (3): 129–135, doi:10.1109/TEI.1971.299145, S2CID 51642905

- ^ Thue, William A. (1997). Electrical Insulation in Power Systems. CRC. pp. 255–256. ISBN 978-0-8247-0106-2.

External links

[edit]Electrical treeing

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Process

Electrical treeing is a pre-breakdown phenomenon observed in solid polymeric dielectrics, characterized by the formation of tree-like conductive channels that progressively degrade the insulation under high electrical stress, ultimately leading to dielectric failure.[6] These channels originate from localized defects such as micro-voids, impurities, or protrusions, where intense electric fields distort the material structure and initiate degradation.[7] Commonly encountered in high-voltage insulation materials like cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE) used in power cables, electrical treeing serves as a critical precursor to complete insulation breakdown in equipment such as transformers and insulators.[7] The process begins with the application of a high electric field, typically exceeding the dielectric strength in localized regions near defects, prompting the inception of partial discharges (PDs).[8] PDs are localized electrical breakdowns within gas-filled voids or channels, producing ionized gas pockets that generate heat, high-energy electrons, and reactive chemical species; these erode the surrounding polymer matrix, creating initial hollow tubular paths resembling tree branches.[8] As PD activity intensifies, the degradation propagates outward in a branched manner, with the channels widening and extending through the insulation toward the opposite electrode, driven by continued field enhancement and material erosion.[6] This stepwise advancement—starting from micro-scale voids and evolving into macroscopic conductive networks—culminates in a fully bridged path that causes catastrophic failure, often after prolonged exposure to alternating or direct current stresses.[7] At its core, partial discharges play a pivotal role by not only initiating but also sustaining tree growth through repetitive localized breakdowns that degrade the dielectric's molecular chains, producing byproducts like cross-linking or oxidation that further weaken the material.[8] In practical terms, electrical treeing accounts for a significant portion of failures in high-voltage systems, with studies indicating that trees can develop over hours to years depending on stress levels, underscoring the need for early detection to prevent outages in power distribution networks.[7] A typical illustration of electrical treeing depicts a needle-shaped electrode embedded in the dielectric sample, with branched, fractal-like channels emanating from the tip and radiating outward, often visualized under microscopic observation to highlight the dendritic progression from the initiation site.[6]Historical Context

The phenomenon of electrical treeing was first reported in the 1950s during high-voltage testing of polymeric insulation materials, where branching, tree-like degradation channels were observed in substances like polymethylmethacrylate and polyethylene under divergent electric fields. These early observations, primarily attributed to J.H. Mason's experiments, highlighted the role of localized dielectric breakdown and internal partial discharges in initiating such structures, marking the initial recognition of treeing as a distinct failure mode in solid insulators. The term "treeing" was first explicitly used in 1958 by D.W. Kitchin and O.S. Pratt to describe the phenomenon in polyethylene.[9] By the 1970s, further studies, including work by T.W. Dakin and colleagues, advanced this understanding by analyzing treeing type breakdown and its relation to partial discharges, demonstrating how repeated micro-discharges erode insulation and propagate dendritic patterns.[10] Accelerated aging tests emerged as a critical milestone, enabling controlled replication of tree formation under elevated voltages and frequencies to predict long-term insulation reliability in power systems.[10] This period also saw electrical treeing implicated in widespread underground cable failures, particularly in early extruded polyethylene systems, which prompted increased research funding and industry-wide investigations into failure mechanisms.[11] The 1980s brought broader recognition of treeing's contribution to cable breakdowns, with standardized testing protocols developed to assess tree resistance; the terminology "electrical treeing" had evolved from earlier descriptions like "dendritic breakdown" and became standard in dielectric research during this time. Post-2000 advancements have been driven by computational simulations, which have revolutionized modeling of tree initiation and growth by incorporating finite element analysis and stochastic processes to simulate complex propagation dynamics.[10] More recently, from the 2010s to 2025, research has increasingly focused on nanomaterials, such as silica and alumina nanofillers, for suppressing treeing through enhanced charge trapping and interfacial barrier effects in polymer matrices like XLPE.[12] These developments, including studies on nanocomposite dispersion to extend insulation lifespan, reflect ongoing efforts to mitigate tree-induced failures in high-voltage applications.[3]Mechanisms of Formation

Initiation Phase

The initiation phase of electrical treeing is triggered primarily by high electric field stress, typically exceeding 10 kV/mm, concentrated at defects such as impurities, voids, or electrode protrusions within the insulating material. These localized high fields lead to electron avalanches, which initiate partial discharge (PD) activity by accelerating free electrons and causing ionization in the surrounding medium.[13] In polymeric insulations like cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE), such defects create sites where the electric field is amplified, often by orders of magnitude, promoting the onset of degradation channels that evolve into tree structures.[14] Key processes during initiation include field emission of electrons from triple points—interfaces between solid insulation, gas, and electrode surfaces—followed by streamer inception, where gaseous discharges form conductive filaments.[13] Additionally, electromechanical stress induced by the electric field can cause micro-cracking in the polymer matrix, further facilitating PD inception by creating new void-like defects.[15] A unique factor in the initiation phase is the accumulation of space charge, where injected electrons become trapped in the insulation, distorting the local electric field and exacerbating stress concentrations.[14] This trapping mechanism creates heterogeneous field distributions, with positive space charge near the electrode enhancing the field ahead of it, thereby accelerating PD onset. Experimental evidence from needle-plane electrode setups, commonly used to simulate protrusions, demonstrates that space charge dynamics under AC stress significantly influence the probability and rapidity of tree initiation in XLPE samples.[14] The time scale for initiation varies widely depending on the applied stress: under high AC or DC fields exceeding 10 kV/mm, it can occur in seconds due to rapid PD escalation, whereas in operational service conditions with lower average stresses (around 5 kV/mm or less), initiation may take hours to years as cumulative damage builds. This phase sets the foundation for subsequent propagation, though the overall treeing process begins with these initial degradation events.[15]Propagation Phase

Once initiated, the propagation phase of electrical treeing involves the progressive expansion of tree channels through the dielectric material, driven primarily by partial discharge (PD) activity that erodes the insulation. Repetitive PDs generate localized heating and reactive species, leading to the formation of carbonized channels that extend the tree structure.[16] This erosion is complemented by streamer propagation mechanisms, where high-energy electrons cause impact ionization, accelerating the creation of conductive paths within the polymer matrix.[17] The velocity of tree propagation depends strongly on the local electric field strength, often modeled empirically as , where is the propagation velocity, is the local electric field, and , , and are material-specific constants reflecting activation barriers and field enhancement effects.[18] Propagation typically begins with slow initial growth at rates of approximately 0.1–1 μm/s, transitioning to accelerated phases where velocities increase to several μm/s as channels widen and fields intensify, ultimately culminating in rapid breakdown.[19] Chemically, this phase involves the breakdown of polymer cross-links, particularly in materials like polyethylene, releasing gaseous hydrocarbons such as methane and ethane through PD-induced decomposition.[20] A key dynamic in propagation is the establishment of feedback loops, wherein emerging tree branches distort the electric field distribution, enhancing local fields at branch tips and promoting further branching in a self-reinforcing manner; this process yields self-similar fractal patterns with dimensions typically between 1.5 and 2.0, observable in cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE) samples.[21] Additionally, mechanical stress arises from gas pressure buildup within the hollow channels, which can temporarily halt or redirect growth by exerting outward forces on the channel walls.[20] Experimental modeling of propagation often employs phase-field simulations to predict growth paths, incorporating field-dependent degradation and stochastic elements; these models have been validated against laboratory observations in XLPE insulation subjected to voltages of 10–50 kV, accurately reproducing observed branching and acceleration behaviors.[4]Types and Morphologies

Electrical Tree Variants

Electrical trees exhibit distinct morphological variants depending on factors such as applied voltage, frequency, and material properties, primarily categorized as branch, bush, and fibrillar trees.[10][22] Branch trees feature sparse, elongated channels that propagate linearly, typically forming under uniform electric fields and lower stress conditions, resulting in slower growth rates.[10] These structures resemble dendritic patterns and are commonly observed in polyethylene insulation, where they develop as tree-like extensions from defect sites.[10] In contrast, bush trees consist of dense, compact structures that form spherical or bush-like clusters, exhibiting rapid growth under high electrical stress and elevated frequencies above 10 kHz.[10][22] These are prevalent in epoxy resins, where the material's transparency aids observation of the multi-branched, uniform morphology.[10] Fibrillar trees represent a hybrid variant, combining a main trunk-like channel with branching extensions reminiscent of both branch and bush forms, often classified as fibrillar due to their intermediate density and structure.[22] Growth behavior varies with voltage type; alternating current (AC) at power frequencies like 50 Hz tends to favor branch-like propagation, while direct current (DC) conditions, particularly under polarity reversal, promote denser bush-like morphologies with higher branch density.[23][10] Filamentary trees, characterized by thin, channel-like paths, differ markedly between media: in solid dielectrics, they form permanent structures with fractal geometry on timescales of hours, whereas in gases, they manifest as transient discharges without lasting channels.[24] Under impulse voltages, such as lightning surges, electrical trees display rapid "stop-go" growth patterns, where propagation alternates between accelerated extension and stagnant phases due to intermittent charge dissipation and field redistribution, as observed in phase-field simulations of combined AC/DC-impulse stresses in the 2020s.[25]Comparison with Water Trees

Water trees represent a distinct form of degradation in polymeric insulation, primarily driven by electrochemical processes resulting from moisture ingress under combined electrical and environmental stresses. Unlike electrical trees, water trees form hollow, tubular channels filled with water or ionic solutions, without the involvement of partial discharges (PD), and exhibit slower growth rates typically on the order of millimeters per year in wet environments. These structures arise through mechanisms such as stress-induced electrochemical degradation (SIED), where oxidation and ion diffusion create hydrophilic microcavities, leading to progressive insulation weakening over extended periods.[26][27] In contrast, electrical trees are initiated and propagated by PD activity in dry conditions, resulting in rapid growth—often spanning hours to days—and the formation of carbonized, conductive paths that directly lead to dielectric breakdown. Water trees, however, rely on diffusion-based transport of water and ions, necessitating the presence of moisture, and typically manifest as bow-tie (internal, symmetric) or vented (surface-originating, outward-growing) morphologies that do not immediately compromise conductivity. A key distinction lies in the absence of significant electrical conductivity in water tree channels until an electrical tree forms to bridge them, at which point PD can initiate catastrophic failure.[26][27][28] Hybrid degradation often occurs in cables, where water trees precede and facilitate the development of electrical trees, forming combined "bow-tie" structures that accelerate overall failure. Water trees are a major cause of premature failures in cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE) cables, particularly in underground or subsea installations exposed to moisture, with studies indicating they contribute significantly to insulation breakdowns in service-aged systems during the 2020s.[28][29]Influencing Factors

Electrical and Stress Factors

Electrical tree initiation and growth are profoundly influenced by the magnitude of the applied voltage and the resulting electric field strength. In alternating current (AC) systems, higher root mean square (RMS) voltages exceeding 5 kV significantly accelerate tree propagation in cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE) insulation, with growth rates increasing nonlinearly due to intensified partial discharge activity and bond scission.[30] For instance, experiments applying 12 kV AC RMS have shown initial branch-like trees of approximately 20–100 μm after application, compared to slower development at lower voltages.[31] Direct current (DC) stress introduces space charge accumulation, which distorts the local electric field and exacerbates tree formation, particularly at electrode-insulator interfaces. The field perturbation due to this buildup in cylindrical geometry is described by the equation where is the space charge density, is the radial distance, and is the permittivity of the material. This distortion can enhance the effective field by factors of 1.5–2, lowering the energy barrier for defect initiation and promoting polarity-dependent treeing under negative DC bias.[32][33] Frequency variations in the applied voltage also modulate tree dynamics, with partial discharges playing a key role in degradation. At power frequencies like 50 Hz, partial discharge magnitudes are moderate, but increasing to the kilohertz range elevates discharge intensity and repetition rate, accelerating tree branching due to cumulative thermal and chemical effects.[34] Impulse voltages, such as those with steep rise times below 1 μs, induce rapid propagation, often forming dense bush-like structures within seconds by triggering avalanche ionization.[35] The uniformity of the electric field further dictates tree susceptibility, with inhomogeneous fields—characterized by sharp gradients near defects or electrodes—facilitating initiation at lower overall voltages than homogeneous fields, as local peaks exceed critical thresholds. Superposed stresses, including mechanical vibrations at amplitudes of 0.1–0.5 mm, enhance tree growth rates by 20–50% through induced microcracks that align with field lines, amplifying partial discharge pathways. As of 2025, dynamic mechanical strain has been shown to accelerate tree growth and narrow tree geometries in XLPE insulation, with height-width ratios doubling under applied strain.[36] For XLPE, the threshold field for reliable tree initiation is approximately 20 kV/mm under standard needle-plane configurations, aligning with updated IEEE testing protocols for high-voltage insulation.[38]Material and Environmental Factors

The properties of dielectric materials significantly influence the initiation and propagation of electrical trees. In semi-crystalline polymers such as polyethylene (PE), electrical trees preferentially develop along amorphous regions due to their lower volume resistivity and higher susceptibility to electric field concentration compared to crystalline domains, conferring greater overall resistance to treeing in semi-crystalline structures than in fully amorphous polymers.[39][40] The incorporation of fillers, such as silica nanoparticles, enhances breakdown strength in polymer matrices; for instance, dispersed silica nanoparticles have been shown to increase dielectric breakdown strength by more than 15% under AC and DC conditions, with optimal loadings mitigating defect-induced tree growth.[41] Environmental conditions also play a critical role in electrical treeing dynamics. Elevated temperatures above 60°C soften the polymer matrix by increasing molecular mobility, thereby reducing tree inception voltage and accelerating propagation rates, as observed in XLPE insulation where higher temperatures lead to faster tree growth under constant voltage.[42] Humidity contributes indirectly by promoting void formation through moisture absorption, which creates sites for partial discharges and tree initiation, though unlike water trees, it does not involve direct hydrophilic pathways.[43] Aging processes further predispose materials to electrical treeing. Oxidative degradation during thermal aging alters the polymer's chemical structure, increasing permittivity and facilitating defect formation that lowers the threshold for tree initiation in materials like XLPE.[44] In nuclear applications, radiation exposure accelerates treeing by generating defects such as cross-links and chain scissions in cable insulation, reducing lifetime and breakdown strength as evidenced in electron beam-irradiated XLPE.[45] Recent advancements highlight the role of material modifications in suppressing treeing. Nanocomposites have demonstrated tree suppression through improved interfacial polarization and reduced space charge accumulation in high-voltage insulation. Voids larger than 10 μm serve as a critical threshold for tree initiation, as smaller voids sustain partial discharges without permanent erosion, while exceeding this size leads to rapid tree channel formation.[20]Detection and Diagnosis

Detection Techniques

The primary methods for detecting electrical treeing involve monitoring partial discharges (PDs) that occur during the initiation and propagation phases, as these discharges generate characteristic signals across multiple domains. Electrical detection captures current pulses from PD events using high-frequency current transformers (HFCT) or pulse capacitive couplers, which measure the fast-rising transients associated with tree channel formation in solid insulation like cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE).[46] Acoustic detection employs ultrasound sensors operating above 100 kHz to record pressure waves emanating from PD-induced voids within the tree structure, providing non-invasive assessment of degradation in cables and transformers.[47] Optical techniques detect ultraviolet (UV) emissions from excited gas molecules in PD sites using photomultiplier tubes or UV-sensitive cameras, offering direct insight into the luminous nature of discharges in epoxy or polymer insulations.[48] Phase-resolved partial discharge (PRPD) analysis enhances detection by correlating PD amplitude and occurrence with the phase angle of the applied AC voltage, producing diagnostic patterns that distinguish electrical treeing from other insulation faults. These patterns, often visualized as 2D or 3D plots, reveal characteristic features such as clustered discharges in the rising voltage quadrant for branch-type trees, enabling early identification of tree growth stages.[49] PRPD data from simulated tree channels in low-density polyethylene demonstrate PD magnitudes increasing from microcoulombs to millicoulombs as trees propagate, with pulse sequence analysis further quantifying inter-pulse timing to assess degradation severity.[50] Advanced detection methods include ultra-high frequency (UHF) sensing, which captures broadband electromagnetic emissions from PDs up to 1 GHz using internal antennas in gas-insulated switchgear (GIS), applicable to tree-like defects in composite insulations.[51] Chemical analysis complements these by identifying gaseous byproducts such as acetylene (C₂H₂) generated from polymer decomposition in tree channels, quantified via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to indicate arcing-level degradation in epoxy resins under high stress.[52] Detection thresholds are established through PD inception voltage (PDIV) measurements, defined as the minimum voltage triggering detectable PDs (>5-10 pC), which precedes tree initiation and varies with material and frequency—typically 5-10 kV for XLPE needle tests.[53] Statistical evaluation employs the Weibull distribution to model PD height distributions and predict failure probability, where shape parameters (β >1) indicate consistent tree-related PD escalation, as observed in accelerated aging experiments on cable insulations.[54] Artificial intelligence-based approaches, such as machine learning classifiers applied to PRPD patterns, have improved automated detection, with bagging tree algorithms achieving 89.79% accuracy in distinguishing electrical tree PDs from voids or surface discharges in laboratory and field datasets.[55] These methods process features like histogram of oriented gradients (HOG) and principal component analysis (PCA) on PD signals, facilitating real-time monitoring in high-voltage cables as demonstrated in recent studies.[55]Localization Methods

Localization methods for electrical trees focus on pinpointing the spatial position and structural extent of these degradations within insulating materials, enabling targeted maintenance in high-voltage apparatus such as cables and transformers. These techniques build upon initial detection signals, such as partial discharges, to provide precise mapping essential for evaluating insulation integrity without invasive disassembly. Electrical tomography, particularly using capacitance or impedance mapping, reconstructs the internal dielectric distribution to identify permittivity variations caused by tree channels and associated voids. This non-invasive approach employs electrode arrays around the insulation to measure mutual capacitances, from which tomographic algorithms generate 2D or 3D images of anomalies. For instance, electrical capacitance tomography has been adapted to visualize low-contrast features in polymer dielectrics, offering resolution suitable for detecting early-stage treeing in laboratory samples.[56] Acoustic emission triangulation represents a practical in-situ method, utilizing an array of piezoelectric sensors placed on the equipment surface to capture ultrasonic waves generated by tree propagation. The location is determined by calculating time-of-arrival differences across sensors, applying geometric triangulation to estimate the source coordinates with sub-millimeter precision in controlled environments. In power transformers, this technique has demonstrated localization accuracy approaching 1 mm for partial discharge sources linked to treeing, though signal attenuation limits effectiveness in insulation thicker than 10 cm, where wave dispersion and multiple reflections complicate resolution.[57] X-ray computed tomography (CT) and related imaging provide high-fidelity visualization of tree morphologies in post-mortem or lab-based analysis, scanning samples to produce volumetric reconstructions of channel structures. This method excels at resolving fine branching details, with voxel resolutions down to micrometers, as demonstrated in studies of electrical trees in epoxy and polyethylene insulations.[58][59] Advanced techniques include adaptations of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for polymers, leveraging low-field nuclear magnetic resonance to map void distributions that precede or accompany treeing. These methods detect hydrogen-rich regions in degraded insulation, offering non-destructive insights into early degradation sites without ionizing radiation.[60] Time-domain reflectometry (TDR), particularly for elongated structures like cables, injects fast-rising pulses and analyzes reflection times to locate impedance discontinuities potentially caused by tree degradation, with meter-scale accuracy along cable lengths up to kilometers, though more established for water trees.[61] In the 2020s, progress has included drone-mounted ultra-high-frequency (UHF) antennas for non-contact localization of partial discharge emissions in overhead line insulators, enabling rapid surveys over extensive networks.[62] Furthermore, integration of localization data with geographic information systems (GIS) supports real-time 3D modeling of power network faults for predictive maintenance visualization.Prevention and Mitigation

Design and Engineering Strategies

Design principles for preventing electrical treeing in high-voltage systems emphasize minimizing electric field concentrations and eliminating manufacturing defects that serve as initiation sites. Stress grading at cable joints, often achieved using semiconductor or nonlinear materials such as zinc oxide microvaristors or functionally graded composites, redistributes electric fields to reduce peak stresses below critical thresholds like 10 kV/mm, thereby suppressing partial discharges that initiate treeing.[63][64] For instance, these materials can lower tangential fields by up to 70% under stress cones in HVDC joints, homogenizing the field distribution and mitigating degradation at interfaces.[65] Similarly, void-free extrusion processes during cable manufacturing, such as post-cross-linking vacuum degassing at 120–150°C under low pressure, reduce micro-void densities to below 10² per mm³, enhancing the perforation gradient and preventing void-induced tree propagation.[66] Operational strategies focus on pre-service and ongoing assessments to address potential defects before they evolve into trees. Voltage conditioning through dielectric withstand tests, such as very low frequency (VLF) AC or DC overvoltage applications, identifies and burns out incipient defects in insulation, ensuring reliability prior to energization and avoiding tree initiation during operation.[67] Regular partial discharge (PD) monitoring, guided by IEC 60270 standards for high-voltage test techniques, enables early detection of tree precursors through apparent charge measurements, with scheduled offline or online tests recommended for aged cables to maintain insulation integrity.[68] At the system level, incorporating redundant insulation layers in cables and transformers provides a barrier against tree propagation, allowing continued operation if initial degradation occurs in one layer while distributing stresses more evenly.[69] Finite element analysis (FEA) is employed to optimize electric field distributions in transformer designs, simulating insulation geometries to minimize hotspots that could foster treeing, often integrating nonlinear material properties for accurate prediction of field gradients under operational loads.[70][71] Unique strategies include active cooling systems to keep insulation temperatures below 50°C, as elevated temperatures accelerate tree initiation by reducing inception times and enhancing charge mobility in polymers like XLPE.[19] In HVDC lines, surge arresters limit transient overvoltages from lightning or switching, significantly reducing the risk of impulse-induced treeing by clipping peaks and lowering insulation stress levels, with studies showing overvoltage reductions up to 58% in hybrid configurations.[72][73]Material Enhancements

To inhibit electrical tree initiation and growth, dielectric materials are modified through the incorporation of additives and advanced techniques that enhance charge trapping, reduce partial discharge (PD) byproducts, and improve overall stability. Nano-fillers, such as 1-3 wt% silica (SiO₂) nanoparticles, are dispersed into polymers like epoxy resin to create deep electron traps that capture high-energy carriers, thereby suppressing PD activity and tree propagation. For instance, in epoxy composites, 1 wt% nano-SiO₂ doping increases the tree inception voltage by 24% compared to pure epoxy across temperatures from 20°C to 100°C, while also extending breakdown lifetime by up to 71.4% at 60°C.[42] Similarly, cross-linking agents in cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE) insulation, such as peroxides, form a three-dimensional network that boosts thermal stability and restricts molecular mobility under electrical stress, reducing the likelihood of tree channel formation during aging.[74] Doping techniques further refine material performance by introducing voltage stabilizers, particularly aromatic compounds like polycyclic aromatics or benzophenone derivatives, which act as electron scavengers to prevent hot-electron accumulation at defect sites. In silicone rubber, grafting aromatic hydrocarbon stabilizers increases tree inception voltage by 14.5% at 30°C, 42.5% at 50°C, and 46.0% at 70°C relative to unmodified material, while promoting denser, bush-like tree morphologies that slow propagation.[75] Hybrid composites incorporating graphene nanoplatelets (0.001-0.005 wt%) into silicone rubber or epoxy enable conductivity grading, where the fillers form percolation networks that distribute electric fields more uniformly and inhibit tree branching; at 0.005 wt%, graphene reduces average tree length by up to 50% under AC stress.[76] Performance enhancements from these modifications are evident in accelerated aging tests, where nanofilled epoxies exhibit prolonged resistance to tree inception, with inception voltages rising significantly (e.g., 24-46% depending on filler and stabilizer type). In XLPE cables, such material upgrades correlate with extended operational lifetimes, often doubling breakdown times in treeing simulations compared to base polymers.[42][75] Emerging concepts include self-healing polymers embedded with microcapsules containing healing agents, such as in dielectric elastomers, where tree propagation ruptures capsules to release agents that cross-link and repair micro-cracks autonomously; this restores electrical resistance to levels comparable to pristine material (around 2 × 10¹³ Ω·m) and boosts re-treeing inception voltage by approximately 30%.[77] For eco-friendly alternatives, biodegradable polymers like bio-based polypropylene (derived from renewable sources such as sugarcane) offer recyclable insulation with equivalent tree resistance to XLPE, minimizing environmental impact while maintaining high dielectric strength and longevity in high-voltage applications.[78]References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/397085937_The_Influence_of_Dynamic_Mechanical_Strain_on_the_Electrical_Treeing_Characteristics_in_XLPE_Insulation