Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

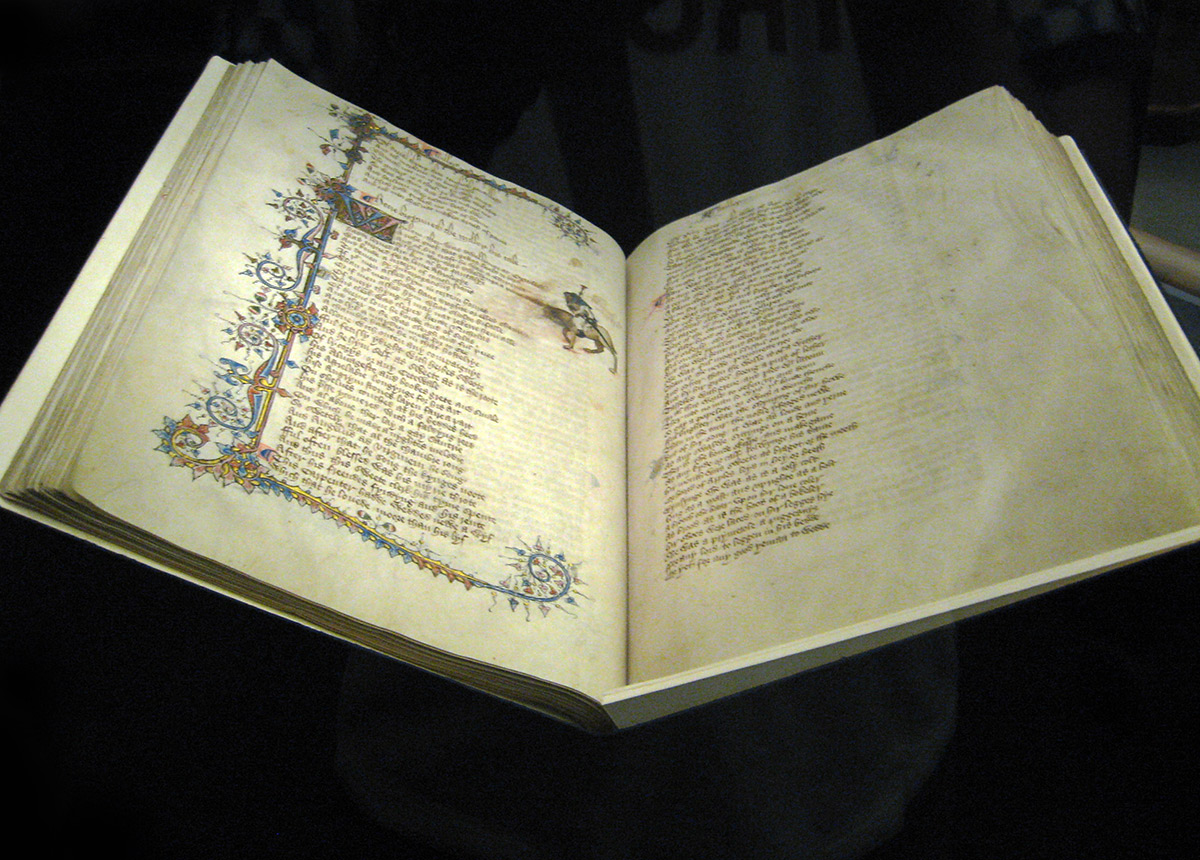

Ellesmere Chaucer

View on Wikipedia

The Ellesmere Chaucer, or Ellesmere Manuscript of the Canterbury Tales, is an early 15th-century illuminated manuscript of Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, owned by the Huntington Library, in San Marino, California (EL 26 C 9). It is considered one of the most significant copies of the Tales.

History

[edit]Chaucer scholarship has long assumed that no manuscripts of the Tales exist dating from earlier than Chaucer's death in 1400. The Ellesmere manuscript, conventionally dated to the first decades of the fifteenth century, would therefore be one of the first extant manuscripts of the Tales. More recently, the manuscript has been dated to c. 1405 or earlier, leading to speculation that it "was conceived as an immediate response to Chaucer's death by those eager to commemorate his memory through the appropriate preservation of his work."[1]: 60 It has even been suggested that, while the final sentence of the manuscript ("Here is ended the Book of the Tales of Canterbury, compiled by Geffrey Chaucer, of whos soule Iesu Crist have mercy. Amen.") makes it clear that Chaucer had died by the time the manuscript was finished, Ellesmere could have been begun while the poet was still alive.[2]: 208

The early history of the manuscript is uncertain, but it seems to have been owned by John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford (1408–1462). The manuscript takes its popular name from the fact that it later belonged to Sir Thomas Egerton (1540–1617), Baron Ellesmere and Viscount Brackley, who apparently obtained it from Roger North, 2nd Baron North (1530/31–1600).[3] The library of manuscripts, known as the Bridgewater Library, remained at the Egerton house, Ashridge, Hertfordshire, until 1802 when it was removed to London. Francis Egerton, created Earl of Ellesmere in 1846, inherited the library, and it remained in the family until its sale to Henry Huntington by John Francis Granville Scrope Egerton (1872–1944), 4th Earl of Ellesmere. Huntington purchased the Bridgewater library privately in 1917 through Sotheby's. The manuscript is now in the collection of the Huntington Library in San Marino, California (EL 26 C 9). It was published in facsimile in 1911,[4] then reproduced again in colour in 1995.[5]

Because the manuscript was in the Bridgewater Library for centuries, early scholars working on Chaucer's works were unaware of its existence and it was not consulted for any early editions of the Tales. It first came to public notice following its description in 1810; the text was not available until 1868, when it was edited by F. J. Furnivall.[1]: 62–63 W. W. Skeat's 1894 edition of the Tales was the first to use Ellesmere as the basis for its text.[1]: 63

Description

[edit]The Ellesmere manuscript is a highly polished example of scribal workmanship, with a great deal of elaborate illumination and, notably, a series of illustrations of the various narrators of the Tales (including a famous one of Chaucer himself, mounted on a horse).

The manuscript is written on 240 high-quality parchment leaves of approximately 394 by 284 mm (15+1⁄2 by 11+1⁄4 in) in size.[1]: 59

Illuminations

[edit]Owing to the quality of its decoration and illustrations, Ellesmere is the most frequently reproduced Chaucer manuscript.[1]: 59

In order of appearance in the Ellesmere Chaucer (note that not all storytellers have an illumination):[6]

- Knight (fol. 10r)

- Miller (fol. 34v)

- Reeve (fol. 42r)

- Cook (fol. 47r)

- Man of Law (fol. 50v)

- Wife of Bath (fol. 72r)

- Friar (fol. 76v)

- Summoner (fol. 81r)

- Clerk of Oxford (fol. 88r)

- Merchant (fol. 102v)

- Squire (fol. 115v)

- Franklin (fol. 123v)

- Physician (fol. 133r)

- Pardoner (fol. 138r)

- Shipman (fol. 143v)

- Prioress (fol. 148v)

- Chaucer (fol. 153v)

- Monk and his greyhounds (fol. 169r)

- Nun's Priest (fol. 179r)

- Second Nun (fol. 187r)

- Canon's Yeoman (fol. 194r)

- Manciple (fol. 203r)

- Parson (fol. 206v)

Scribe and its relation to other manuscripts

[edit]The Ellesmere manuscript is thought to be very early in date, being written shortly after Chaucer's death. It is seen as an important source for efforts to reconstruct Chaucer's original text and intentions, though John M. Manly and Edith Rickert in their Text of the Canterbury Tales (1940) noted that whoever edited the manuscript probably made substantial revisions, tried to regularise spelling, and put the individual Tales into a smoothly running order. Up until this point the Ellesmere manuscript had been used as the 'base text' by several editions, such as that of W. W. Skeat, with variants checked against British Library, Harley MS 7334.

The manuscript is believed to have been written by a single scribe, the same scribe who wrote the Hengwrt Manuscript of the Tales. The scribe has been identified as Adam Pinkhurst, a man employed by Chaucer himself; however, the attribution is controversial, with many palaeographers remaining undecided for or against.[7] If the scribe was employed by Chaucer directly, this would imply that the reconstructions hypothesized by Manly and Rickert were carried out by someone who had worked with Chaucer, knew his intentions for the Tales, and had access to draft materials.

The Ellesmere manuscript is conventionally referred to as El in studies of the Tales and their textual history. A facsimile edition is available.

-

The beginning of The Knight's Tale from the Ellesmere Manuscript

-

The opening page of The Wife of Bath's Tale from the Ellesmere Manuscript of The Canterbury Tales, circa 1405–1410

-

Geoffrey Chaucer from the Ellesmere Manuscript

-

The Friar from the Ellesmere Manuscript

-

Robin the Miller from folio 34v of the Ellesmere Manuscript of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales

-

Roger the Cook from Ellesmere Manuscript

-

The Summoner from the Ellesmere Manuscript

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Edwards, A.S.G. "The Ellesmere manuscript: controversy, culture and the Canterbury Tales." Essays and Studies, vol. 2010, annual 2010, pp. 59+. Gale CA254401568

- ^ Simpson, James (2022). "The Ellesmere Chaucer: The Once and Future Canterbury Tales". Huntington Library Quarterly. 85 (2): 197–218. doi:10.1353/hlq.2022.0014. ISSN 1544-399X.

- ^ "Guide To Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the Huntington Library". Archived from the original on 2009-04-12. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ^ Chaucer, Geoffrey (1990). The Ellesmere manuscript of Chaucer's Canterbury tales: a working facsimile (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge: Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-187-0.

- ^ Chaucer, Geoffrey (1995). Woodward, Daniel (ed.). The Canterbury Tales: the new Ellesmere Chaucer faksimile; (of Huntington Library MS EL 26 C 9). Tokyo: Yushodo [u.a.] ISBN 978-0-87328-151-5.

- ^ The Storytellers in order of appearance in the Ellesmere Chaucer. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

- ^ Kerby-Fulton, Kathryn (2024-07-01). "Adam Pinkhurst and the Baffled Jury: Assessing Scribal Identifications within the Margin of Error". Speculum. 99 (3): 664–687. doi:10.1086/730564. ISSN 0038-7134.